6 minute read

2.2. Feathers Market

In ostrich farms, conducted mainly in South Africa, Florida and in California during the plume boom, the birds were denuded of their feathers at regular intervals. The first feathers were plucked when the bird was a year old, and then every succeeding year when the bird had grown back full mating plumes. Three hundred feathers could be ‘harvested’ from a single ostrich in its lifetime. Unusually the feathers on both the male and female were equally valuable, as they were mostly dyed before being put on the market. Similarly all of the ostrich plumes of commerce were really double plumes, made by uniting two of the natural feathers, so as to appear fuller.

Birds of all kinds were used for both their feather and bodily appearance. Ostrich, heron, peacock and bird of paradise were enormously popular, but common garden fowl, such as pigeon, turkey and goose were also used. Feathers were put through several stages of processing before they were ready to be attached to hats. In the final forms they were known to the trade as plumes, pompons, aigrettes, breasts, wings, pads, bands (that would to encircle the crown or to outline the brim), and quills. The table below (taken from the 1912 edition of Millinery by Charlotte Rankin) illustrates what kinds of feathers were made up into each of the various forms of ‘branching’ or ‘pasting’.

Advertisement

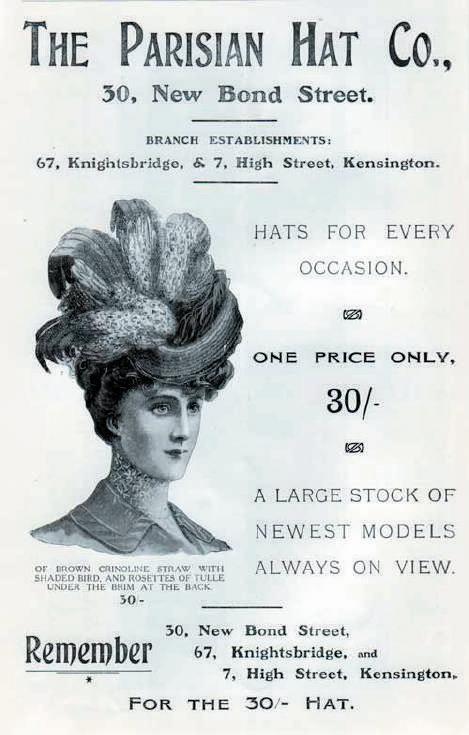

The thirst for exotic ornament among fashionable women in the metropoles of Europe and America prompted a bustling global trade in ostrich feathers that flourished from the 1880s until the First World War. South African ostrich plumes, due to their particularly sumptuous nature, were so in demand during this period that their value per pound was almost equal to diamonds.

Advert for The Parisian Hat co. in the London Saturday Review 1864.

To meet all the feather-processing demands of milliners and ladies of fashion feather workshops, known as plumassiers, opened. In these workshops feathers were dyed and made into arrangements from boas to aigrettes to tufts and sprays for both the worlds of fashion and interiors. The Encyclopedia Britannica’s entry on ‘Ornamental Feathers’ from 1901 explains what the ‘arts’ of the plumassier encompassed:

In the early part of the 20th century there were over 425 feather makers (plumassiers) in Paris, the centre of the trade at the time. While plumassier workshops in Paris concentrated on the preparation and handling of very fine and valuable exotic feathers demanded by high-end modistes, or milliners, New York’s entrepreneurial Lower East side fostered the emergence of pop-up plumage sweatshops.

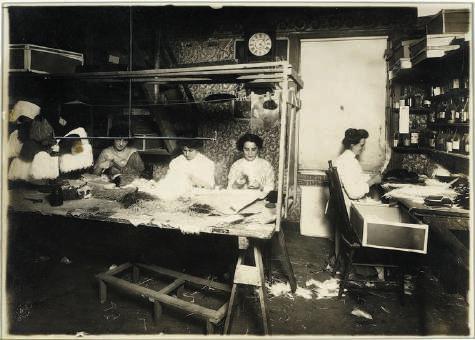

By 1900, As Stein outlines in her 2008 book Plumes…, the North American millinery industry employed 83,000 people (which equated at the time to 1 of every 1000 Americans). In the oppressive New York plumage sweatshops young women and girls prepared feathers for sale, usually for vey low wages. Stein also states the women and girls were also prone to tuberculosis, due to the dust and fluff. One of the most onerous jobs was ‘willowing’, which consisted of lengthening the short strands, called flues, of inferior feathers by tying on one, two or three flues until the feather has the desired depth and grace.

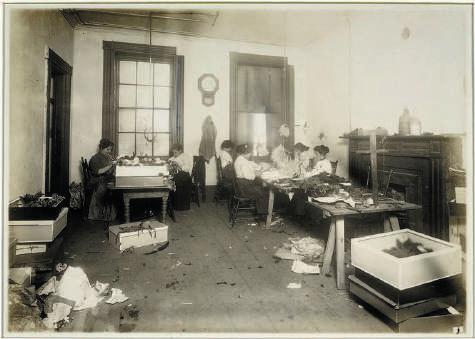

PHOTO 01: Willowing, stringing and steaming feathers in New York plume sweatshop PHOTO 02: Cluttered workroom in a New York feather sweatshop PHOTO 03: Making trimmings, New York Plumassier (ca. 1907-ca. 1933) Photo © L. W. Hine/ NYPL Digital Collection PHOTO 01

PHOTO 02

PHOTO 03

The willowing of ostrich feathers was very common, so as to ensure plumes fitted the desired depth and length expected by milliners and department stores and their customers. The willowing of feathers was so in demand that often women would take home large bags of feathers to willow at home.

In the process of willowing, each tiny feathery fiber is lengthened by having several lengths of the same kind knotted to it, a tedious, fine and demanding process. The result is a plume with long, sweeping feathers.

Naturally coloured feathers were bleached white before they were dyed so they would take the intended colour better (this is why the feathers of the naturally white Snowy Egret were so in demand as they side-stepped this stage of the process). Naturally white feathers by comparison were simply washed in bundles of hot soapy water, and then run through pure warm water. If the end color was to be light, the dye liquor could be applied cold, but darker shades required a cold water dye-bath first, and then slow heating until the water was very hot—though never boiling – so that the feather would take the dye.

The quill and butt, or end of the feather, were dyed first. The tip and flues were dyed after because the former parts could take up to twenty or thirty minutes to absorb the color, whereas the tip and flues would take the dye in two minutes. If the stem did not take the color thoroughly enough, it often had to be painted afterwards.

The black dyeing of feathers was apparently the trickiest. Using logwood dye, which was considered the best for the purpose, took about six days. Feathers were sometimes also painted with oil paint and gasoline, but the color often rubbed off. Another undesired effect of this method was that the thick oil paint often plastered the tiny barbules together.

After being dyed feathers were thoroughly rinsed in warm water and then laid on paper to dry and covered with powdered dry starch to fluff the feathers again after the dying process. It was then the job of the young women to either willow or shape the feathers depending on what type of feathers or trimmings they were working on.

The barbs could then be curled by drawing them singly over the face of a blunt knife or by the application of a heated iron. Ostrich feathers frequently had to be treated with acid and glycerin to give the flue greater flexibility.

When so treated they were generally used in aigrette form or branched in some novel way. This method was known in the trade as ‘burnt ostrich’.

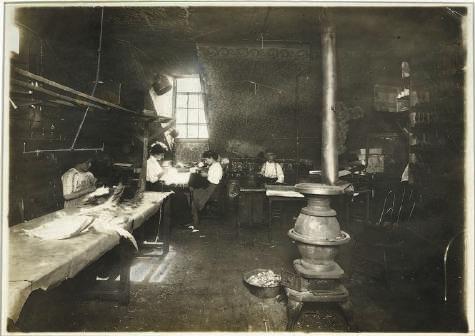

The photographic series above depicting women at work in plumage sweatshops are taken from Lewis W. Hine’s photographic series documenting working conditions in New York, 1905-1939. Hine was an American sociologist and photographer who used his camera as a tool for social reform. His photographs, highlighting the plight of children and immigrants working in New York sweatshops, were instrumental in changing the child labor laws in the United States.

However even with mounting pressure from workers rights movements and conservation lobbies, the plume industry stood fast against claims of worker exploitation and animal cruelty and offered the public false assurances. For instance industry officials claimed that the bulk of feather collection was limited to shed plumes, however in truth, those ‘dead plumes’ brought only one fifth of the price of the live unblemished ones.

Yet as the new more enlightened century unfolded, protests began to be heard. In America the Audubon society and in the UK the RSPB (Royal Society for the Protection of Birds) campaigned to persuade ladies not to use plumage for their own adornment and to ban both national and the international plum trade. One writer in 1875 declared that the beauty of these birds “tempts the most tender-hearted to condone the practice. It was reckoned in 1895 that some twenty to thirty-million dead birds are imported annually to supply the demands of murderous millinery.”

PHOTO 04: Feather making. PHOTO 05: Process of feather making in plume sweatshop, N.Y. (ca. 1907-ca. 1933) Photo © L. W. Hine/ NYPL Digital Collection PHOTO 04

PHOTO 05