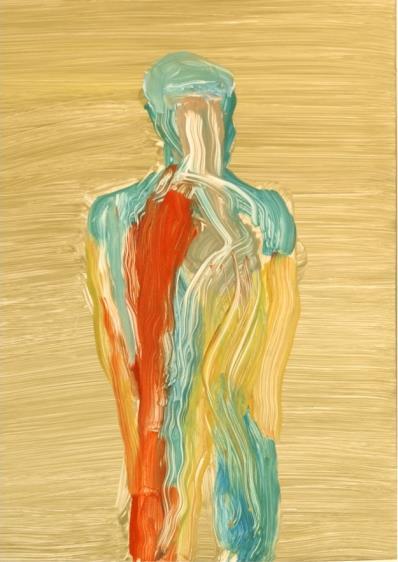

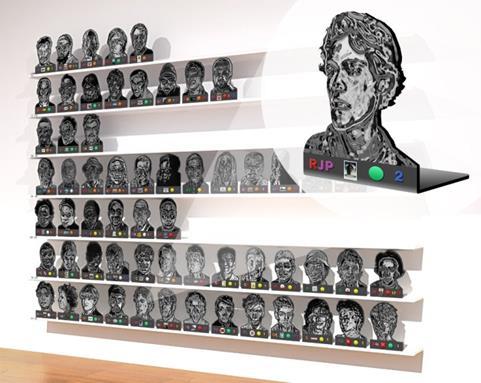

Artists on cover:

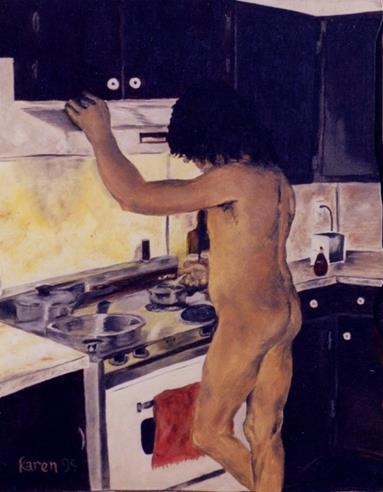

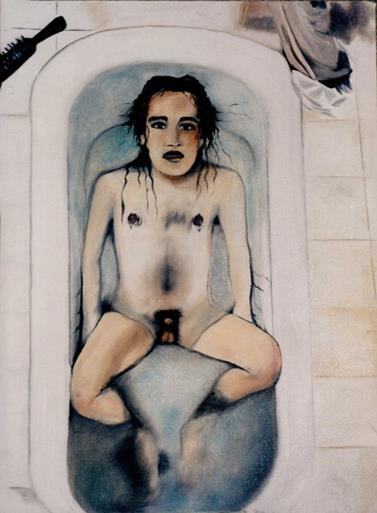

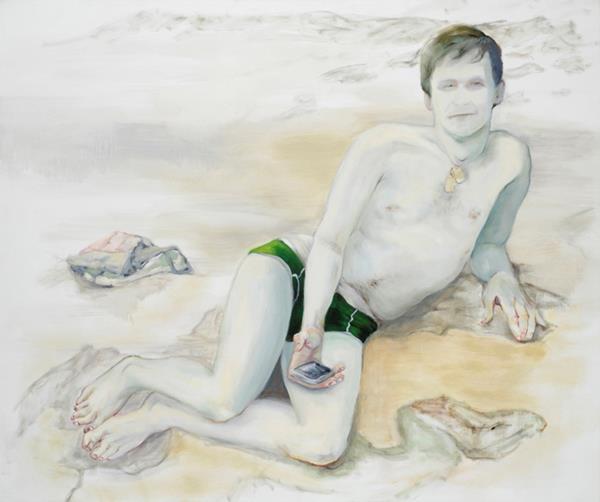

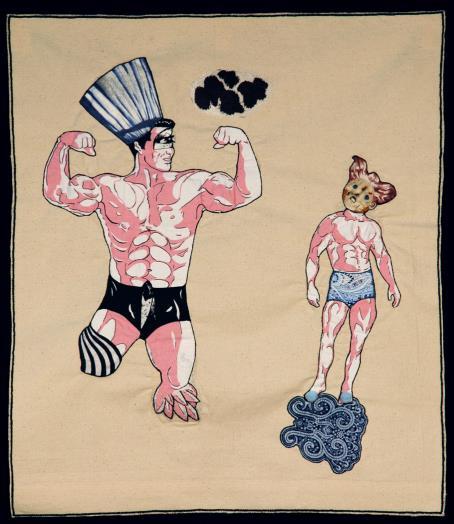

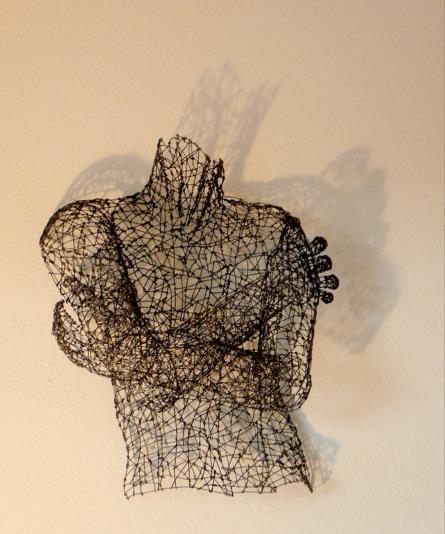

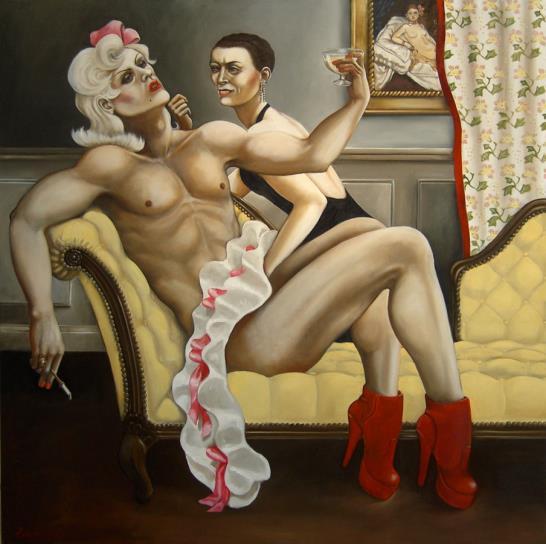

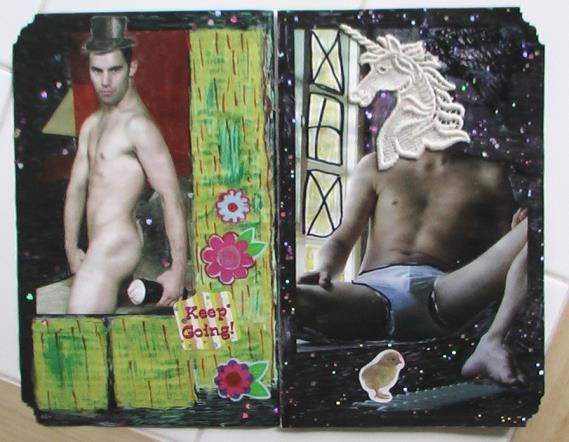

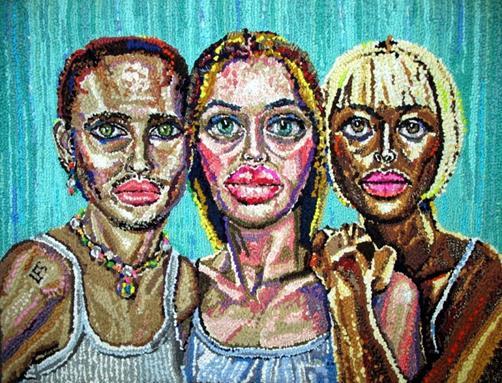

(left, top to bottom) Karen Zack, Emily Yost, Sita Mae, Della Calfee

(middle) Della Calfee

(right, top to bottom) Arabella Decker, Xian Mei Qlu , Laura Hartford, Molly Marie Nuzzo, Juana Alicia

Copyright 2011 by the Women’s Caucus for Art. The book authors and each artist here, retain sole copyright to their contributions to this book.

Catalogue edited by Tanya Augsburg and designed by Karen Gutfreund.

Cover Design by: Rozanne Hermelyn

Arc and Line Communication and Design

www.arcandline.com

ISBN: 978-0-9831702-0-4

2

Organized

by

KAREN GUTFREUND

Edited by TANYA AUGSBURG

MAN AS OBJECT: REVERSING THE GAZE

Women’s Caucus for Art

SOMArts Cultural Center, San Francisco, California November 2011

Kinsey Institute Gallery, Bloomington, Indiana April to June 2012

3

4 CONTENTS 5 Notes from the Director Karen Gutfreund 6 Notes from the President Janice Nesser-Chu

From Inception to Erection: The Birth of Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze Brenda Oelbaum 14 Introduction: Some Starting Points, Theories, and Themes Tanya Augsburg 33 FEATURED ARTISTS 38 Complicit Object—Reversing the Gaze Lynn Hershman Leeson 47 On Shooting Men Annie M. Sprinkle

The Ethics of the Female Gaze—The “Sex” Act of a Woman Behind the Camera Melissa P. Wolf

SELECTED ARTISTS

10

56

59

DIRECTOR’S NOTES

Karen Gutfreund

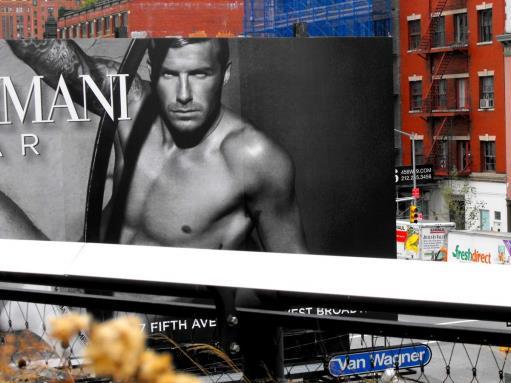

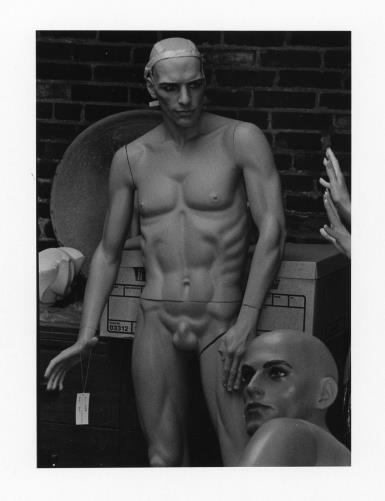

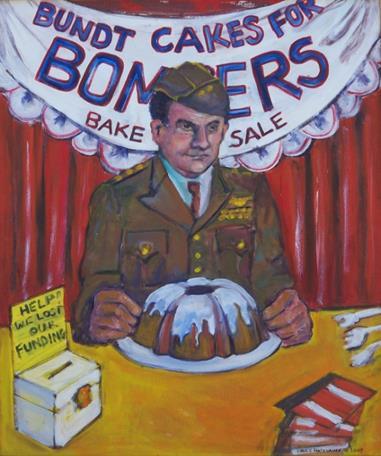

Looking at Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze, I’m reminded of what Linda Williams wrote in the 1994 catalogue, What She Wants: Women Artists Look at Men: “How shall I regard these sexual images of men made by women artists? Is this erotic art? Is this pornography?” I’ve been working with the exhibition's images of men for 18 months from our initial call for art and quite frankly, sometimes the viewing experience is overwhelming. Let's face it: there are a lot of penises in the show. I recently attended the Berkeley, CA screening of !WAR Women Art Revolution by Lynn Hershman Leeson and I was astounded by the footage of the senators ranting on about the vaginal imagery in Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party. Just what is going to be said about our “cockfest”?

Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze began with Brenda Oelbaum’s idea for an exhibition where the tables would be turned women would objectify men and really look at them. Women have always been objectified in art; this fact is so fait accompli, but what would happen if we examined men in the same way? Oelbaum threw the proverbial ball and I grabbed it and ran. Male genitalia jokes have abounded throughout the project ever since I met with Priscilla Otani at an In&Out Burger for the hand-off of our initial proposal for SOMArts.

The response to the calls for art was extraordinary! We received entries from over 300 artists. The work and the statements were well thought out and deeply personal. The raw honesty and strength of the diverse voices are a testimony to the creative spirit of these artists. I love how these women assert their voices, loud and unapologetic or quiet and introspective, both from overtly feminist and seemingly non-feminist viewpoints. Can there be a "non-feminist" viewpoint when a women artist represents a man? Men are seen and shown as friends, lovers, objects of desire, fantasy figures, sex toys, eye candy—and occasionally, just simply as male.

We will have 111 works by 105 artists in the gallery and an additional 89 artists in this catalog with 12 invited featured artists and their work. Feminist performance scholar Tanya Augsburg chose the work for this exhibition based on the quality of the work and the statements and for their engagement in feminist social critique. It was an incredible experience to go through all the works and hear Tanya’s interpretations on the relevance to the overall exhibition theme and how they related to historical feminist work. I want to sincerely thank her for her time on this exhibition, which was considerable.

I also want to thank Brenda Oelbaum for her fantastic creative mind and Priscilla Otani for being my anchor. Our volunteer committee and volunteers were fabulous and I want to thank Jessica Gee for publicity, Irma Velasquez, our fiscal secretary and Mel Albhorn for her work on the website, and to Janice Nesser-Chu, President, Karin Luner, Director of Operations and the Women’s Caucus for Art. A big thanks to Rozanne Hermelyn, Arc and Line Communication and Design, for her fabulous cover design; I can’t image doing an exhibition catalogue without her magic. And now onto the show!

5

FROM THE WCA PRESIDENT

I am so very pleased to welcome you to this significant exhibition Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze presented by the national Women’s Caucus for Art. The opening of this exhibition is the precursor to a year-long celebration of the Women’s Caucus for Art’s 40th anniversary in 2012. It serves as a jumping off point for a year that will be marked by exhibitions, lectures, and workshops throughout the country. It seems only fitting that the celebration begins here with a topic that has permeated the discourse in the women’s movement for years and that is as relevant today as it was many years ago.

The topic of the “gaze” has long been written about and discussed. I can remember early in my education reading the now seminal book by Jacques Lacan Écrits. In his writings, Lacan set up a series of trajectories at which identity is formed through the process of looking or gazing at one’s own reflection. Later in my first Women’s Studies class, I encountered the concept of the “male gaze” based on Lacan’s theoretical writings. The “male gaze” has the power to objectify women; to separate one’s self from one’s own body. The gaze allows the viewer to set up a series of beliefs or desires about the person he is looking at. The gaze can exist anywhere in the media, in hierarchal relationships or in the public voice or morals. Since our relationship to objects is based on two things optics and our relationship to what we are looking at, the gaze is also inherent in our experience of things, from what we are taught as a child, to the toys we played with to the images we viewed on TV or movie screen to the music we listened to. The public as well as the private solidifies the notion of what is deemed acceptable, thus

perpetuating the notion of the male gaze.

In Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze the idea of what “is,” is turned on its head. In this exhibition, women artists reverse the gaze and look back at man as object or desire and in doing so they assert their own power and control, not only over their subject but also over their own image and identity. The exhibition is not only about the work on the walls but is about empowerment.

The exhibition features the work of 117 women artists with 124 works in the gallery and an additional 89 artists in the catalogue and also features the work of: Juana Alicia, Nancy Buchanan, the Guerrilla Girls on Tour!, Lynn Hershman, Jill O'Bryan, ORLAN, Carolee Schneemann, the late Sylvia Sleigh, Annie Sprinkle, Elizabeth Stephens, May Wilson and Melissa P. Wolf. I would like to thank the Juror of the exhibition Tanya Augsburg for her selection of the work, her direction and guidance.

I would like to thank the National Exhibitions Director Karen Gutfreund for her vision and the coordination of the exhibition and catalogue; and to the exhibitions committee who put in many hours of hard work to make this exhibition a reality: Brenda Oelbaum, Priscilla Otani, Jessica Gee, Irma Velasquez and Mel Alhborn. I would like to give special recognition to WCA Vice President of the Midwest Region Brenda Oelbaum for being the catalyst to put an idea into motion. And lastly to SOMAarts for not only providing the space but for providing a grant to help fund this exhibition.

So I invite you to come in, to experience, to be moved, to see and to hear the diverse voices and interpretations created by the women artists and art historians who are exhibiting in, and who have written for the catalogue for the Women’s Caucus for Art exhibition Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze. I hope you feel empowered by their voices and vision as much as I do.

Janice Nesser-Chu, President National Women’s Caucus for Art

6

EXHIBITION COMMITTEE

Tanya Augsburg, Juror, Curatorial Committee

Karen Gutfreund, Director, Curatorial Committee

Brenda Oelbaum, Curatorial Committee

Priscilla Otani, Curatorial Committee

Jessica Gee, Publicity

Irma Velasquez, Fiscal Secretary

Women’s Caucus for Art 2010-12 Executive Committee

President: Janice Nesser-Chu, Professor, Director of the Galleries & Permanent Collection, Florissant Valley College, St. Louis, MO

President-Elect: Priscilla Otani, Artist, Partner - Arc Studios & Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Treasurer/Secretary: Margaret Lutze, Adjunct Faculty, Northwestern, DePaul, and Loyola Universities, Chicago, IL

Second VP & Exhibition Director: Karen Gutfreund, Artist, Curator, San Jose, CA

VP for Chapter Relations: Ulla Barr, Artist, San Clemente, CA

VP for Development: Avinger Nelson, Artist, Curator, Pasadena, CA

VP for Organizational Outreach: Sandra Mueller, Founder, Zest Collaborations; Community Artist, A Window Between Worlds,Venice, CA

VP Special Events: Holly Dodge, Contracts/Grants Manager, Academy for Educational Development, Washington, DC

Past President: Marilyn J. Hayes, Painter & Printmaker, Ret. Sr. Prog. Analyst, US EEOC, Arlington, VA

Advisor: Barbara Wolanin, Curator for the Architect of the Capitol, Bethesda, MD

Staff

Director of Operations: Karin Luner, Artist, Gallery Director, Dietzspace, NYC

7

About Women’s Caucus for Art:

The Women's Caucus for Art was founded in 1972, and is an Affiliated Society of the College Art Association (CAA). It is a national member organization unique in its multi-disciplinary, multicultural membership of artists, art historians, students, educators, and museum professionals.

The mission of WCA is to create community through art, education and social activism.

We are committed to:

· recognizing the contribution of women in the arts

· providing women with leadership opportunities and professional development

· expanding networking and exhibition opportunities for women

· supporting local, national and global art activism

· advocating for equity in the arts for all

As a founding member of the Feminist Art Project, WCA is part of a collaborative national initiative celebrating the Feminist Art Movement and the aesthetic, intellectual and political impact of women on the visual arts, art history, and art practice, past and present.

Formoreinformationvisit: www.nationalwca.org

P. O. Box 1498, Canal Street Station New York, NY 10013-1498

info@nationalwca.org

Tel: 212.634.0007

https://www.facebook.com/groups/107511953206/ http://twitter.com/#!/artWCA

8

About SOMArts Cultural Center

The mission of SOMArts Cultural Center is to promote art on the community level, and to foster an appreciation of and respect for all cultures. Founded in 1979, SOMArts embraces the entire spectrum of arts practice and cultural identity, and it is beloved in San Francisco as a truly multicultural, community-built space where cutting-edge events and counterculture commingle with traditional art forms.

Karen Gutfreund and Priscilla Otani, curators of Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze, were one of four 2011-12 Commons Curatorial Residency recipients at SOMArts. Selected artists and curators receive funding support and access to one of the largest and most beautiful gallery spaces in the heart of San Francisco in order to expand their practice, engage the Bay Area’s many cultural communities, and turn vision into reality.

SOMArts programs and exhibitions are supported by the San Francisco Arts Commission’s Community Arts and Education Program, with funding from Grants for the Arts/San Francisco Hotel Tax Fund as well as The San Francisco Foundation.

WWW.SOMArts.org

9

From Inception to Erection: The Birth of Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze

Brenda

Oelbaum

Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of women in herself is male: the surveyed female…thus she turns herself into an object and most particularly an object of vision: a sight.

John Berger, Ways of Seeing

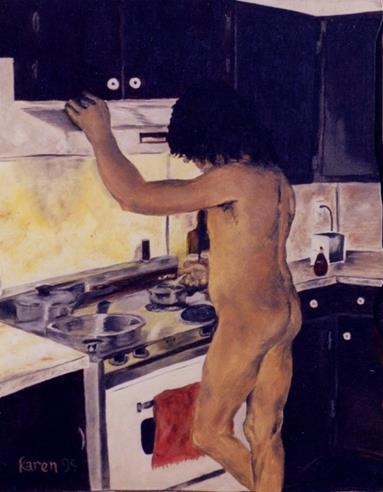

Since the early years of feminist art, feminist artists have responded to their artistic subjugation by male artists by using their own bodies as subject matter in their art. Danica Phelps credits feminist art of the 1970s with giving her and other artists today the “permission to be personal.”1

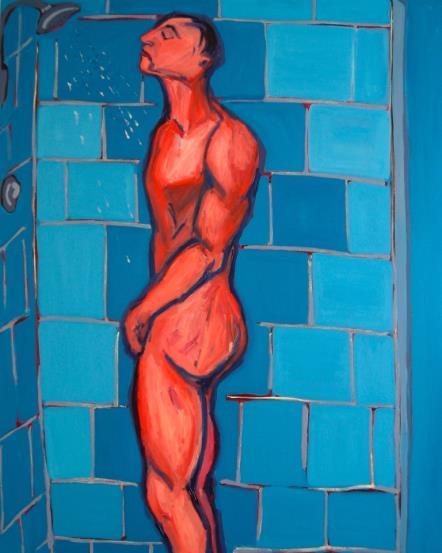

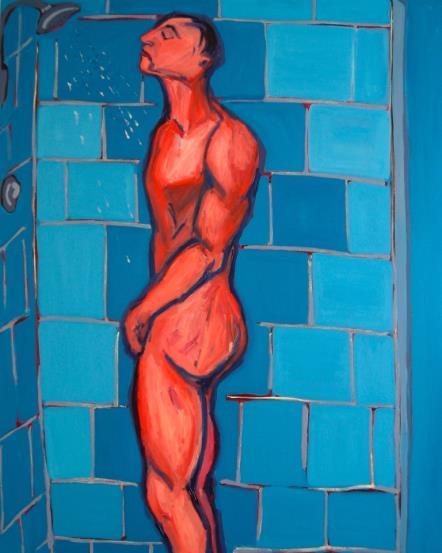

To quote Phelps, “Think of how many male painters have done images of women bathing over the years.” And further, “Part of what makes my work feminist is taking authorship of these images.” She describes her shower drawings as a “reversal of the male gaze.”2

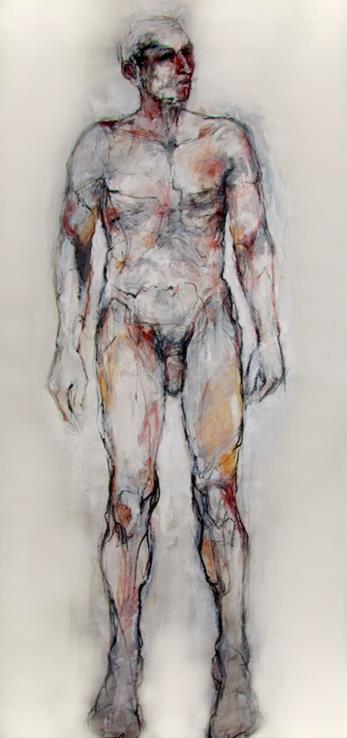

There is a difference in these works from those of our male counterparts. We see the nude woman from different angles. The feminist artist chooses a personal vantage point. The viewer of the work becomes part of the body in the picture, making all viewers, be they male or female, feel as if they are

the subject. The contradiction is, however, that the body is still that of a woman. In men’s portrayals of women the figure in the work is seen from outside, not to say that the perspective cannot be skewed, seen from interesting angles, but it is still from the outside looking in, creating an “otherness,” a clear distinction between the observer and the observed.

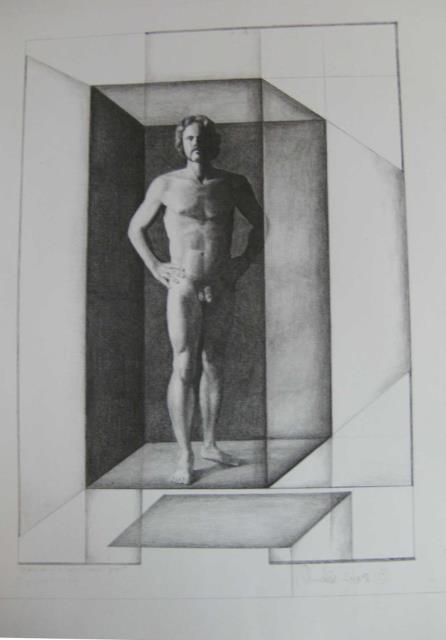

My goal in this exhibit, Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze, is to turn the tables and to exhibit works that put the male in the position of subject and spectacle. Not only will the male be taking on the traditional female role, but the surveyor is now purely female, no longer a “masculine” part of the female, thus creating a truly feminist stance. The male is the spectacle for a woman’s enjoyment or mere viewing.

This is effective in two ways: as the male viewer encounters the male nude, he, as many women before him, is forced to turn the mirror on himself, and secondly, to feel the powerlessness of being owned or submissive.

By reversing the gaze, the individualism of the artist, the thinker, the patron, the owner, and the woman is transformed. The person who is the object of their activities, the man, is treated as a thing or an

10

abstraction. By reversing the unequal relationship between men and women which is so deeply embedded in our culture (to the degree that it still shapes the consciousness of many women), men will do to themselves what they have done to women for centuries. The men depicted here observe themselves and their own masculinity as women observe their own femininity.

This exhibition marks an important development in feminist art, which has long concentrated on images of women meant to challenge stereotypical notions of womanhood. A gallery filled with works created by women depicting men comments on the prevalence of the male gaze in art and of the continued domination of male artists exhibiting in galleries and museums.

In April of 2005 while attending the 25th Anniversary of ArtTable in New York, I was invited by Ferris Olin to represent The Feminist Art Project for the state of Michigan. The job would entail getting universities, galleries, and museums on board in putting together exhibitions and showing works by women from their permanent collections. It also meant encouraging curators to put together feminist themed exhibitions and writing about the work of women artists. My lack of a direct university affiliation was initially problematic, but institutions such as the Kresge Art Museum in East Lansing, Michigan, jumped on board immediately to relabel Miriam Shapiro’s work, which was already hanging in the museum, thus commemorating The Feminist Art Project and defining Shapiro’s significance in the history of the feminist art movement.

of gaining more information in order to advance my own independent curatorial aspirations, I started to think about what type of show I would like to curate for The Feminist Art Project (TFAP ). Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze came directly from attending the ArtTable events, meeting Ferris Olin at gallerist and collector Fredrieke Taylor’s home, and attending the independent curators’ dinner hosted by Margaret (Peekie) Mathews-Berenson and Donna Harkavy. There I would meet Ruth Weisberg, past president of The Women’s Caucus for Art and recent honoree of a WCA Lifetime Achievement Award. In fact, it was from my association with TFAP that I learned about the WCA, which would not be the natural route, since the later had been around for 30 years while TFAP was in its infancy.

I had long wondered why the response of women artists to being objectified in art was to objectify themselves. To me this did not seem like the ideal response. It didn’t turn the camera back on the viewer or man, so to speak, and I wanted to do exactly that. I researched what similar exhibitions had done in the past and found catalogues from several exhibitions in the UK from the 1980s. Then surprise, surprise! I fell on the review in the New York Times of Ellen Altfest’s Men at the I-20 Gallery in New York City. I immediately contacted her to see if she would be willing to jury a similar Women’s Caucus for Art national exhibition. It was actually from our brief dialogue that the exhibition’s full title came to be Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze. Sadly, as a non-profit, WCA did not have the means to pay for such a high profile juror at the time.

Having attended the ArtTable event with the mission

In the spring of 2006 I had the pleasure of meeting ORLAN while she was a guest speaker at the Michigan Theatre for the University of Michigan’s Penny W.

11

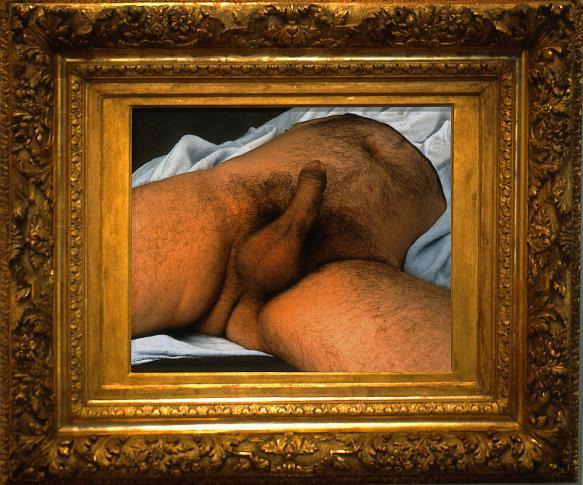

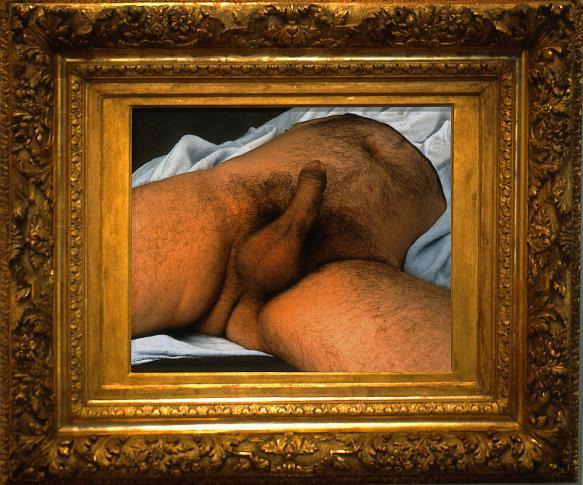

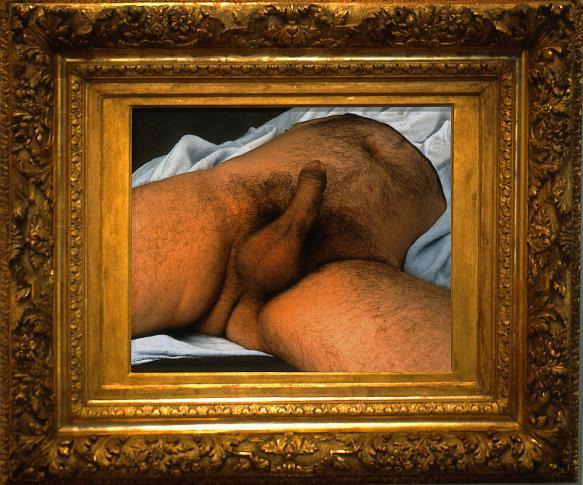

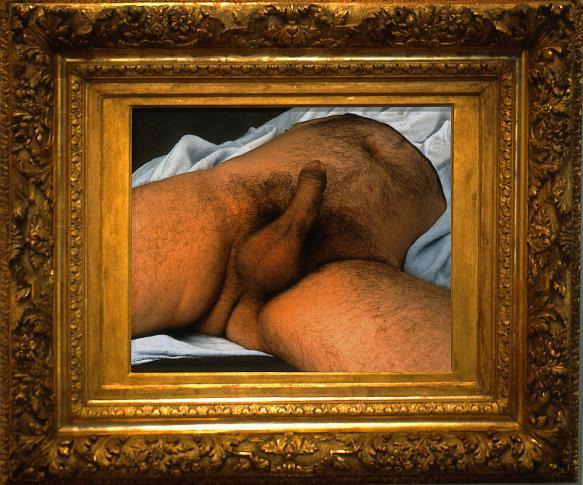

Stamps Distinguished Speaker Series. When I saw her work Origin of War (1989), her response to Gustave Courbet’s infamous painting, Origin of the World (1866), I knew I had the centerpiece of the exhibition. ORLAN’s work was the essence of what I was suggesting for this show. With humor and bravado, ORLAN makes a brilliant riposte to Courbet’s bold commentary.

I envisioned a lenticular3 postcard as the invitation, like the prize in a crackerjack box, where the image would change or move as you handled the card. I saw Courbet’s Origin of the World transforming in a person’s hand from his piece to ORLAN’s Origin of War; female to male in the imagery, male to female

for the artist. It was divine, kitsch, satirical, and ruckus all at the same time, over-the-top and a collector’s item all on its own, a handheld mini-work of art that encapsulated my concept of Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze.

I had heard ORLAN’s discourse about collaborations with computer graphics specialist Pierre Zovilé for her images for The Self-Hybridizations Series: Precolumbian (1998). So with ORLAN's permission we made a contract to print a limited edition of 5,000 lenticular cards.

12

(Left) Gustave Courbet. (1819-1877). The Origin of the World. 1866. Oil on canvas. 18 x 22 inches. 46 x 55 cm. Courtesy of Reunion des Musees Nationaux/Art Resource, NY, Musee d'Orsay, Paris, France

(Right) ORLAN. The Origin of War. 1989. Aluminum-backed Cibachrome. 34 x 40 inches. 102.5 x 87 cm.

When I was approached by Karen Gutfreund in 2010 about a possible follow-up show to California’s highly successful exhibition CONTROL, I told both Karen and Priscilla Otani about my concept for the Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze. I was chock-full of fabulous ideas. I also had great intent and lots of research. I had contacts lined up, including which printers of lenticular art would print what might be deemed pornographic material. I had a list of possible artists to include, the beginnings of essays and prospectus outlines, everything collected over the course of the last six years. It was only with their help and dogged hard work on cleaning things up and making it a cohesive proposal for SOMArts that any of this was possible. Their invitation to

Tanya Augsburg, and their decision to bring her onboard, provided us with an opportunity to include the historic and academic grounding that would give this exhibition its strong foundation and educational relevance.

I am ever so grateful to Tanya Augsburg, ORLAN, the Estates of Sylvia Sleigh and May Wilson, and all the women of the WCA who have banded behind this exhibition, blue chip and/or new chip. It has been so exciting to get an opportunity to work with all of you on such a ground-breaking endeavor.

NOTES

1 Qtd. in Jori Finkel, "Saying the F-Word," ARTnews (Feb. 2007): 118.

2 Ibid.

3 Lenticular printing is a technology in which an array of magnifying lenses is used to produce images with an illusion of depth, or the ability to change or move as the image is viewed from different angles.

13

Introduction: Some Starting Points, Theories, and Themes

Tanya Augsburg

Some Starting Points

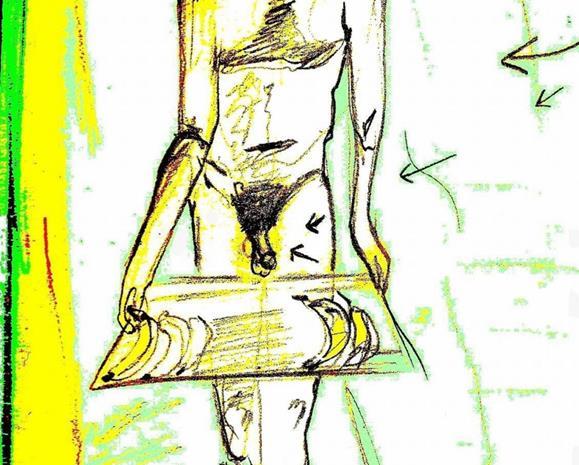

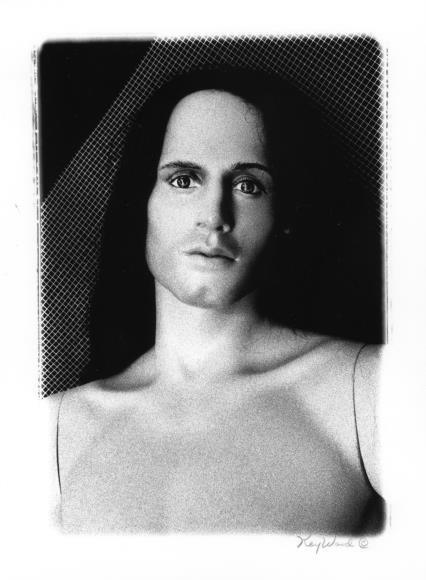

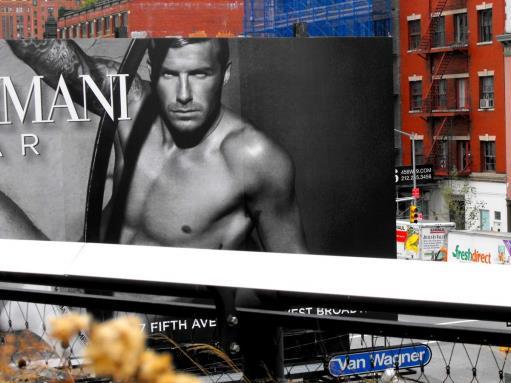

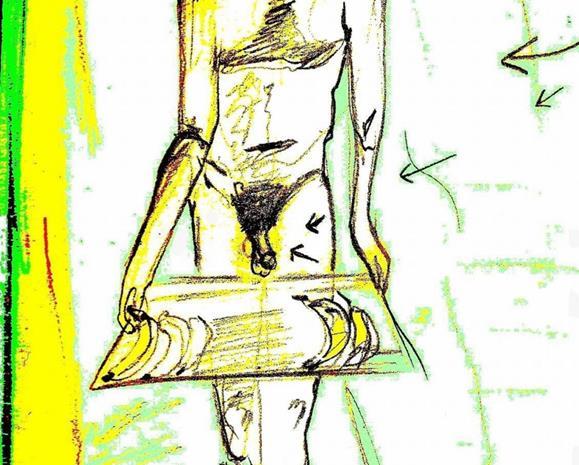

Art history and mass media collided in 1972 over controversies concerning the female gaze. The BBC televised Ways of Seeing, a series created by the art critic John Berger, who declared in its companion text: “men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.”1 That same year during a scholarly panel at the annual conference of the College Art Association art historian Linda Nochlin challenged the masculinist assumptions underlying Berger’s claims. Nochlin compared an erotic photograph from a nineteenth-century French popular magazine of a female nude holding a tray of apples underneath her breasts that was captioned “Achetez des pommes” (which Nochlin translated as Buy My Apples) with her own performative photograph of a male nude model holding a tray of bananas below his exposed penis and scrotum, which she titled, Buy My Bananas. 2 Evidently Nochlin’s photograph was meant to be parodic, not erotic, calling attention to the fact that prevailing cultural norms regarding representations of sexual difference and objectification were not natural. The male nude model with his awkward stance, upturned eyes, and blank facial expression looked clownish, while the visual associations of his penis with bananas seemed way over the top. According to art historian Richard Meyer, Nochlin created a “sensation” with her demonstration of the challenges of objectifying men erotically and aesthetically given existing pictorial conventions.3

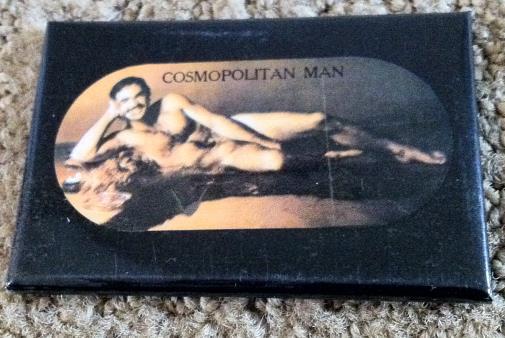

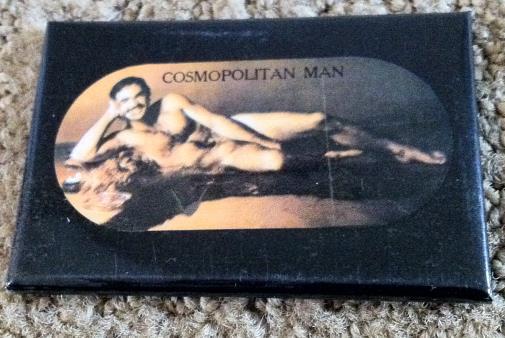

Around the same time, Cosmopolitan magazine editor Helen Gurley Brown commissioned the openly gay fashion photographer Francesco Scavullo to photograph film star Burt Reynolds for Cosmopolitan’s first and to this day, most celebrated nude male centerfold. Reynolds directly faces the camera, lying sideways on top of a bear rug with a wry smile and cigarillo dangling almost perpendicularly from his lips. His lean, muscular body and long legs ambiguously convey both the masculine strength of a football player and feminine grace of a ballet dancer, yet his abundant body hair and full moustache leave no doubt that Reynolds is unequivocally male and macho. An arm strategically covers his genitals, but both the cigarillo and his bottom bent knee jutting towards the camera imply that an erect penis is hiding underneath.

14

Figure 1. Burt Reynolds Cosmopolitan Man Pocket Mirror. Circa 1973. (Photo by Tanya Augsburg, 2011. Photo Courtesy of Tanya Augsburg.)

Nevertheless, Reynolds, like Nochlin’s male nude model, averts the viewer’s gaze with his eyes looking away and outside the camera’s field of vision. While Reynolds is both more subtle with his wayward glance and at ease with his body than Nochlin’s staged banana salesman, he too resists being completely objectified.

The April 1972 Cosmopolitan centerfold is widely recognized as the first male nude centerfold within mainstream American popular culture. In retrospect, editor Gurley Brown could be credited for creating a conceptual art piece—a commodifiable one no less— that paved the way for women to look at men as sexual objects. According to writer Jess Cagle, “Cosmo editor Helen Gurley Brown says that the idea of showing male nudity (Playgirl didn't debut until the next year) came to her while `doing the dishes or something,’ she recalls. `I thought, why wouldn't we enjoy looking at a man's body?’''4 American women agreed. The centerfold image was commodified even further. Posters, calendars, pocket mirrors (Fig. 1), key chains and other memorabilia were made and sold. American women appropriated the image of Reynolds for their own pleasures, and in at least one instance replaced Reynold’s face with those of a boyfriend or husband in merriment and in tribute (Fig. 2). As critic Susan Bordo writes in her 1999 study The Male Body, “the Reynolds centerfold, as tame as it now seems, did represent something of a cultural turning point.”5

Berger’s theoretical premises challenged by Nochlin were resoundingly refuted by Gurley Brown. Surely women actively look at men, and not only that—they thoroughly enjoy it. Berger’s assertions about the ways in which women look and see themselves through the eyes of men pointed towards other

pressing issues for women within art history and the art world: those of education, opportunity, agency, and recognition. Think about it: it is not surprising that women had not been recognized or credited as surveyors of men given that women had not been recognized as cultural imagemakers, i.e., artists. As Eleanor Dickinson has pointed out, H. W. Janson’s 1962 authoritative History of Art textbook included “3000 artists from the Old Stone Age to the Present” with no women.6 Responding to the lack of access to representation in 1972, women stormed out of the aforementioned CAA conference and formed The Women’s Caucus for the Art (WCA).

Nochlin had already raised awareness to these issues when she bluntly asked in an article originally published in 1971, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”7 The question, in Nochlin’s view,

15

Figure 2. Family friends prank Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze curatorial team member and artist Brenda Oelbaum's father on occasion of his 40th birthday, in Toronto, Canada, April 1973. (Photo by Anonymous, 1973. Photo courtesy of the Brenda Oelbaum Collection, Ann Arbor, MI)

was rhetorical; she argues that art history should be asking instead what are the conditions that make great artists possible, pointing out that women were unable to draw male models until the late nineteenth century. How could women artists become great artists if they were not allowed to look at men’s bodies? How could they become recognized as artists if their works were not shown in galleries or museums, let alone were denied opportunities to be able to do their work? Similar problems of lack of education, access, and opportunity existed within other historically male dominated forms of visual culture such as fashion photography and film. To return to our previous example, Gurley Brown had hired a male fashion photographer to photograph Reynolds for women’s visual pleasure, although we can safely assume that she was the one who selected the particular centerfold image out of many others taken.

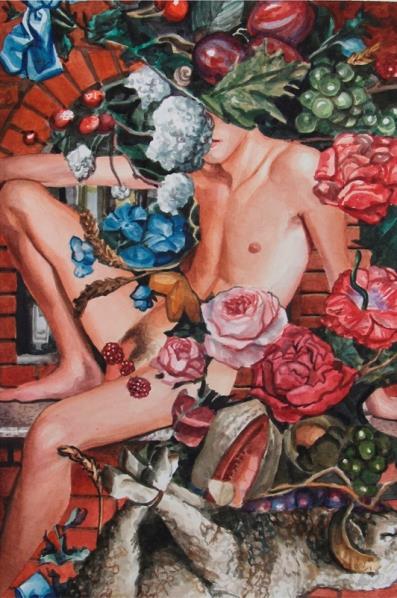

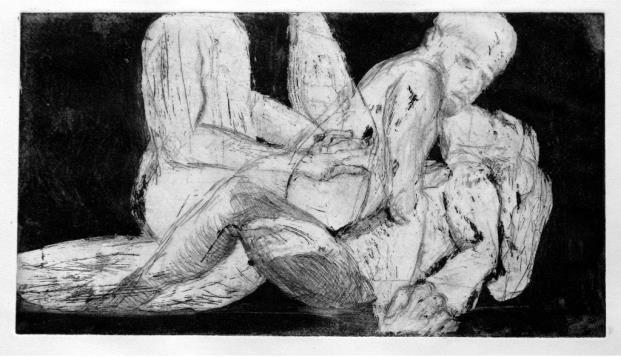

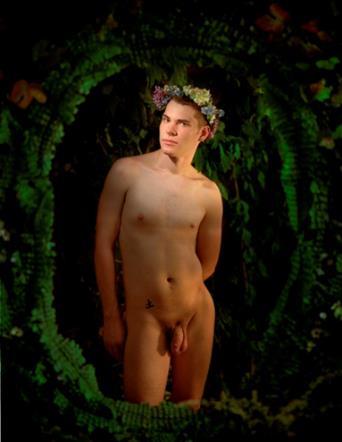

As the country singer Loretta Lynn sang in a 1978 hit song, we’ve come a long way, baby. 8 The art exhibition Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze recognizes and celebrates women and transgender artists looking at men’s bodies from the origins of the feminist art movement, which is usually traced back to 1970-72, to the present. The exhibition includes several earlier works by Carolee Schneemann, Sylvia Sleigh, May Wilson, and Karen Lance Klaber that illustrate feminist consciousness while establishing some of the major thematic theoretical currents of the exhibition that I have explored as Juror: gazing at men and the erotic male body; discerning the phallus; responding to art history; investigating the performativity of masculinity, and contemplating contemporary eroticism. Overall, the featured and juried works in the exhibition were selected for their engagement in feminist social critique.

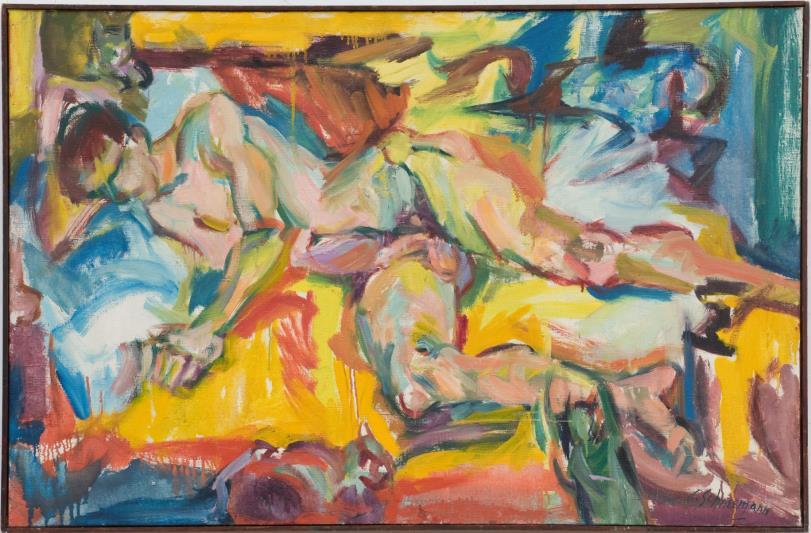

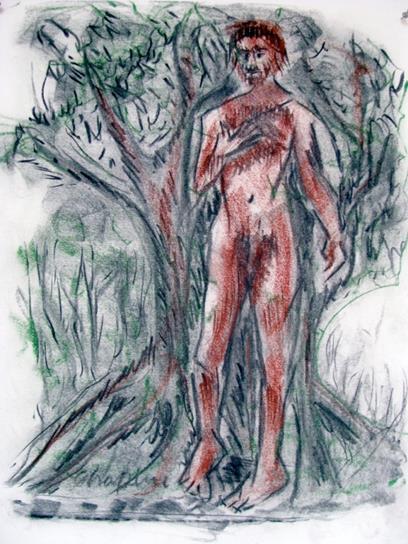

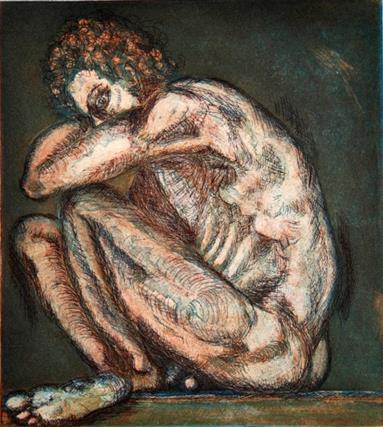

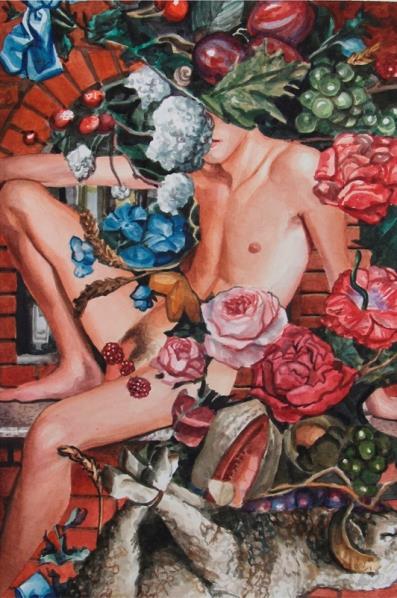

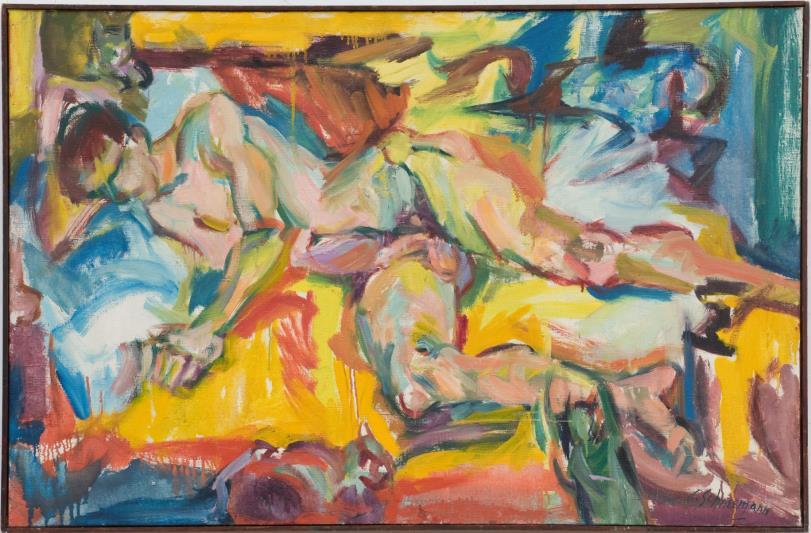

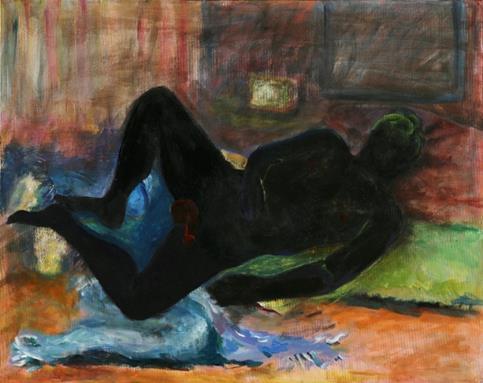

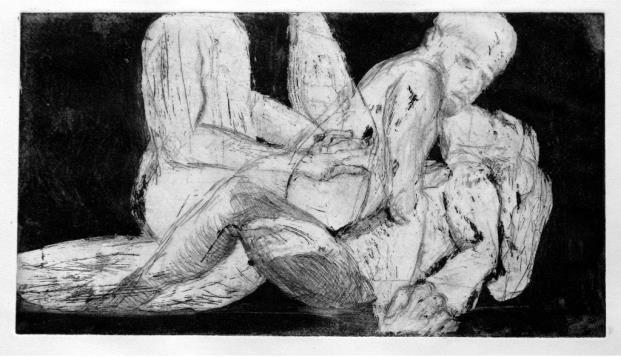

Trailblazing Feminist Artists

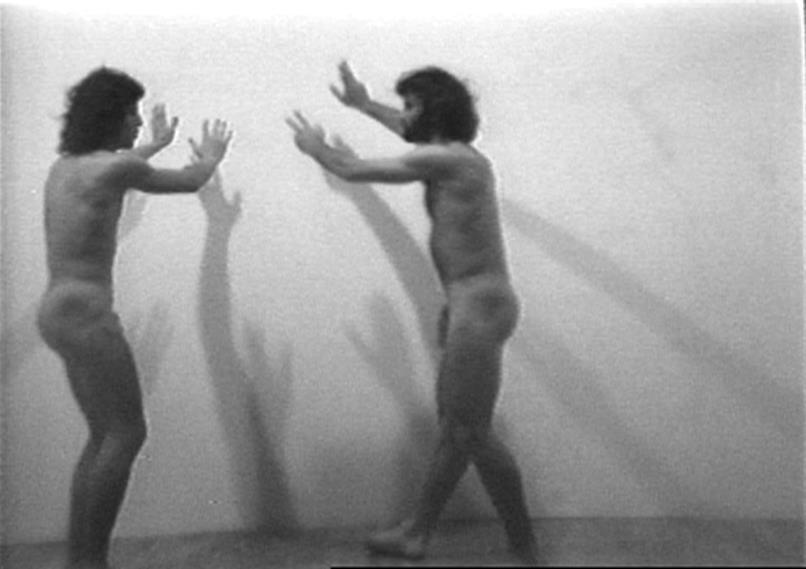

To a great extent Carolee Schneemann’s pioneering film Fuses (1964-67) paved the way for how women artists and filmmakers to look at men erotically, as Schneemann is the first woman artist and filmmaker to make a sexually explicit and erotic film that does not shy away from including her partner James Tenney’s penis within the camera frame. Schneemann’s keen erotic interest in looking at the male body can be seen with her earliest Cezanne inspired paintings, such as Personae: JT and Three Kitch’s (1957). The vibrant image of Tenney in Personae is a good starting point for an exhibition investigating the myriad of ways women artists look at men. In it Schneemann offers her vision of a muscular, reclining Tenney interconnected with his surrounding environment. The viewer’s eye is both drawn to and away from his erect penis as the painting’s center focal point. Tenney appears vividly alive in a state of sexual anticipation even though Schneemann painted him while he was asleep. The painting illustrates Schneemann’s aesthetic interest in movement, prefiguring her subsequent kinetic assemblages and theater.9 Schneemann’s painterly homage to Cezanne marks yet another major strand of this exhibition, as a considerable number of women artists included in the exhibition respond in unique ways to the male dominated history of art.

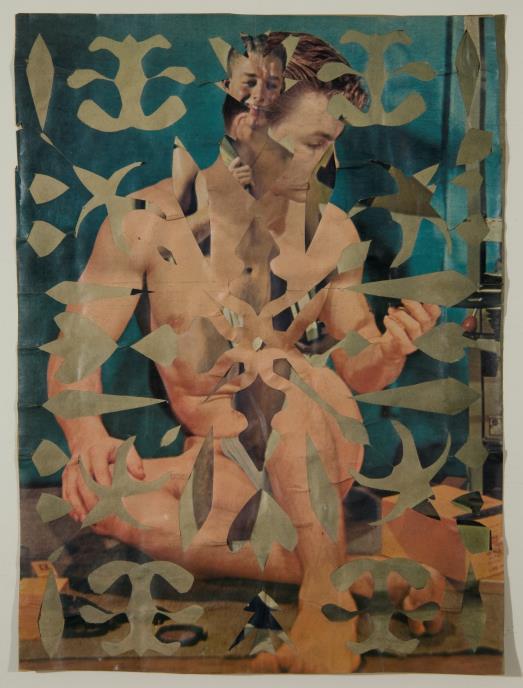

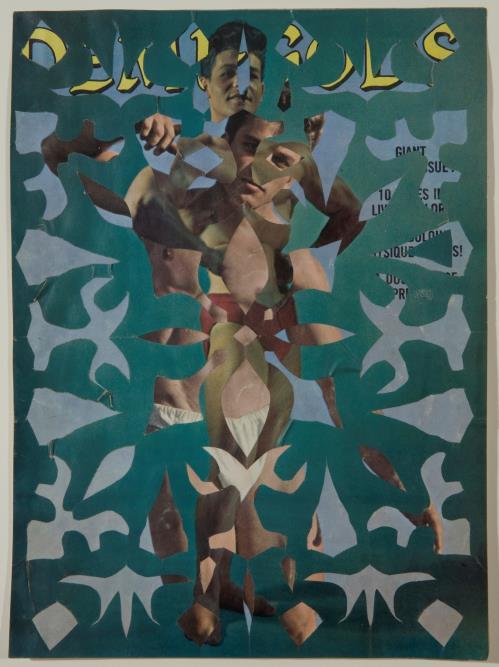

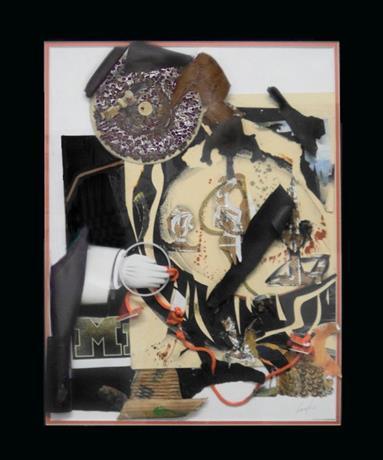

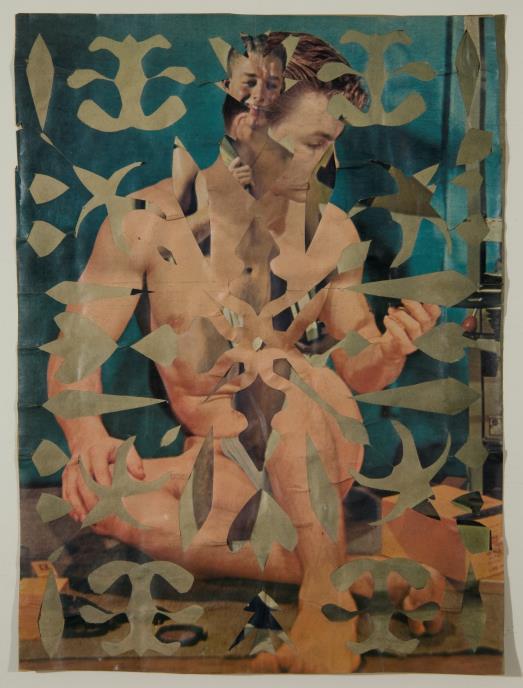

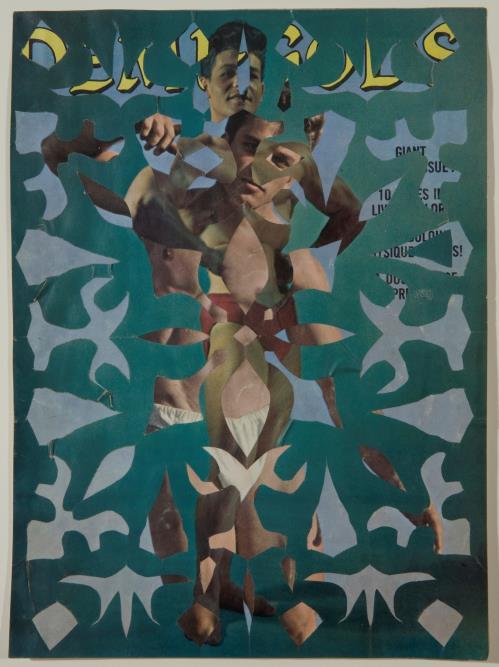

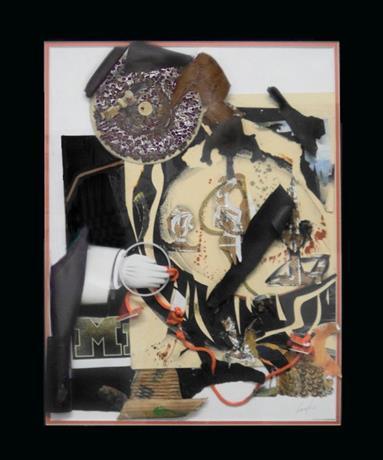

Two of May Wilson’s Snowflake collages from 19651972 lent to the exhibition from the Pavel Zoubok Gallery superimpose snowflake images cut out from gay men’s pornography and muscle men booklets over other images of men from the same sources. Wilson’s technique simultaneously made visible and

16

partially obscured men’s bodies. Do the childlike paper snowflake pattern cutouts render the men more childlike, ridiculous, or desirable? Wilson’s Snowflake collages play with these tensions. Writer William S. Wilson has pointed out that Wilson made these Snowflake collages for friends, particularly “young gay men who wanted to be cured of homosexuality,” trying “to show them acceptance by her, which should encourage self-acceptance.”10 May Wilson’s efforts to advance social justice with her choice of subject matter position her as an important trailblazer for Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze. Moreover, Wilson’s Snowflakes can also be regarded as playful reflections on women’s curiosity and erotic desire to see more of men’s bodies than what was shown in mass media at the time. Viewing Wilson’s collages today, we gain more insight into the reasons why the 1972 Cosmopolitan centerfold with Burt Reynolds became so culturally significant.

Another significant work predating the events of 1972 is Sylvia Sleigh’s 1968 oil painting Lawrence and Susana Delgado. Here Sleigh both anticipates and dramatizes the implications of Berger’s claims. Delgado, a well-known Argentinan artist, sits facing the viewer directly with her legs seductively crossed, fully confident and aware that she is being looked at. With her miniskirt and black thigh high boots Delgado is no wallflower. She is the epitome of the phallic woman in psychoanalytic discourse, the Freudian phantasmorphic image of a woman with a penis and/or its associated symbolic representation, the phallus. Sleigh’s husband, Lawrence Alloway, on the other hand, is positioned sideways, avoiding the viewer and looking tense. He sits with his legs spread apart; his folded hands are resting on top of his crotch. Does he have something to hide or is he protecting his manhood from the potentially castrating female artist’s gaze of his wife and/or of

Delgado? If nothing else Lawrence and Susana Delgado depicts male anxiety when placed in a passive, sexually objectified position. That he is positioned in close proximity of a sexually confident woman under his spouse’s surveillance heightens the sense of male internal conflict.

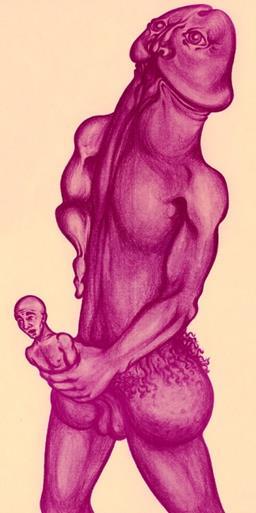

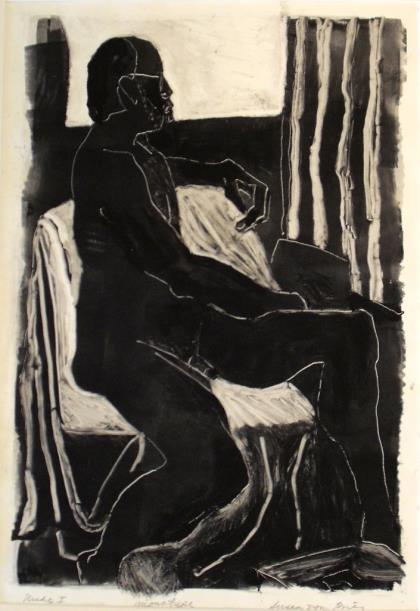

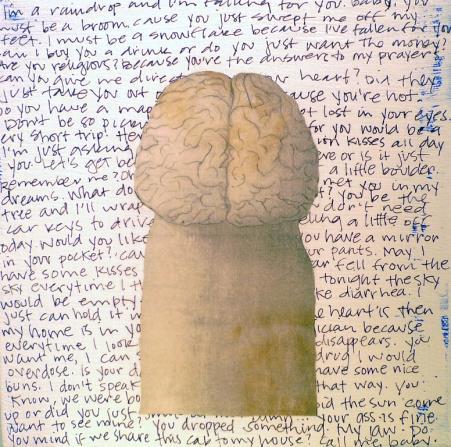

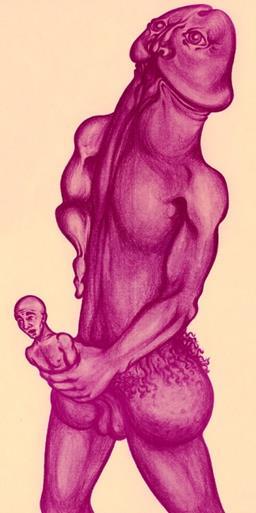

Also included is a print of Karen Lance Klaber’s 1969 charcoal drawing with the ambiguous title, Where’s His Head? Klaber, the publisher of The East Bay Monthly for over four decades, included the following explanation of the origin of the piece with her juried submission: “In 1969, my anthropologist mentor observed that so many men were 'walking around with their heads in their dicks and their dicks in their heads, in a narcissistic trance.' That was the inspiration for this drawing.” Klaber’s satiric drawing calls attention to patriarchal views regarding the phallus. In so doing Klaber renders visible the underlying issue informing a great deal of dominant and domineering masculine attitudes, demeanors, and behaviors: many men’s unfaltering belief in phallic power just because they have penises. Looking at Klaber’s drawing, I can’t help but wonder: What do women artists really think when they look at men nowadays? And what aspects pertaining to men and masculinity are grabbing the attentions of women artists?

Relevant Preceding Art Exhibitions

Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze builds upon the recent explosion of interest in feminist art and feminist art history as evidenced by the successes of recent blockbuster feminist art survey exhibitions

WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution (2007), Global Feminisms (2007), Elles@CentrePompidou (2009), Modern Women: Women Artists at the Museum of Modern Art (2010) and the critical

17

acclaim for !WAR: Women, Art Revolution (2010), Lynn Hershman Leeson’s extraordinary documentary about the history of the feminist art movement. The brainchild of artist and curatorial team member Brenda Oelbaum, Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze was organized on a shoestring budget with a purely volunteer curatorial team and staff. It was organized in two parts: a representative historical section with works spanning from the late 1950s to the 1990s, and a contemporary juried survey. Almost 300 women and transgender artists submitted nearly 900 works for consideration, which gives some indication of the interest in the exhibition’s themes. Sponsored by the Woman’s Caucus for the Art (WCA), Man As Object was made possible by a curatorial residency at SOMArts in San Francisco awarded to Karen Gutfreund and Priscilla Otani, a successful DIY donor drive, and the generosity of an anonymous donor.

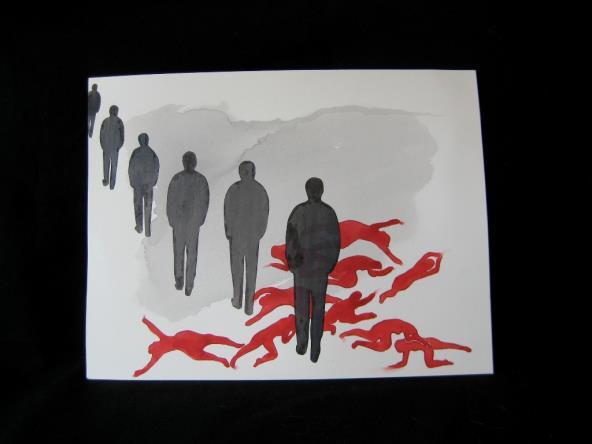

The exhibition’s focus has several significant precedents. In 1975 the Queens Museum in Flushing, New York organized a small exhibition titled Sons & Others: Women Artists See Men, under the direction of Janet Schneider and Kenneth Kahn. Sylvia Sleigh was a participant. The Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London featured several exhibitions of women’s work in 1980, with Women Looking at Men rousing much controversy for what one critic deemed its “forest of penises” while breaking previous attendance records before touring. 11 As its curators Sarah Kent and Jacqueline Morreau remarked in the Preface of the accompanying exhibition catalogue:

A group of women artists was daring openly to challenge some of the basic assumptions of the culture. Whereas, for instance, a male artist is free to show pictures of the female nude and to share intimacies with

his audience, a reversal of these roles is not welcomed. When a woman picks up the brush, chisel or camera and focuses her attention on the male, she invites an avalanche of patriarchal opprobrium. Men prefer to cling on to their own versions of reality than to accept the unpalatable fact that a woman’s view may undermine carefully protected masculine myths.12

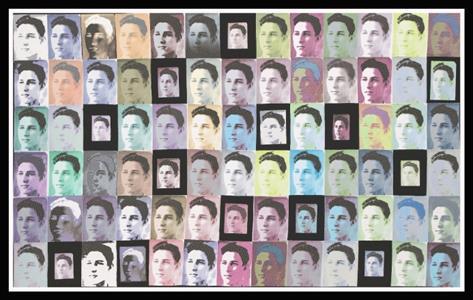

A narrower focus can be gleaned from the 1993 Exhibition What She Wants: Women Artists Look at Men, which was, according to its curator Naomi Salaman, “developed in response to the anti-pornography arguments of the late 1980s, to explore the other side of the debate in terms of visual practice. . . . The exhibition is conceived as an experimental reversal of erotic traditions, consisting of photographic work by over sixty women artists selected from an open submission held over the summer of 1992.”13 In 1994 more that 70 art works were shown as part of The Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary Art exhibition that was curated by Thelma Golden at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Serving as a corrective to negative racial stereotypes, this controversial exhibition also included representations of black males in film, television, and rap music. More recently, I-20 Gallery’s 2006 exhibition Men was organized by painter Ellen Altfest and Chicago’s A+D Gallery’s 2007 show Girl on Guy was curated by Marci Rae McDade. Both shows included work by Sylvia Sleigh.14

A Commitment to Diversity

So, given what has already transpired do we really need another exhibition dedicated to women’s images of men? The simple answer is yes, and for

18

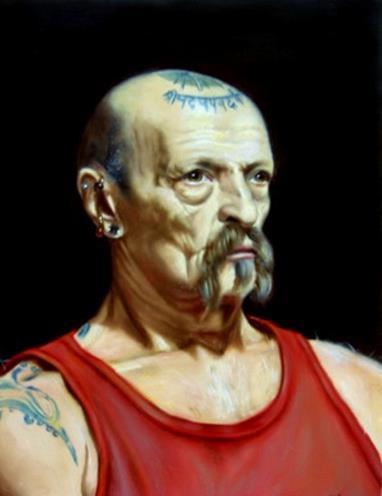

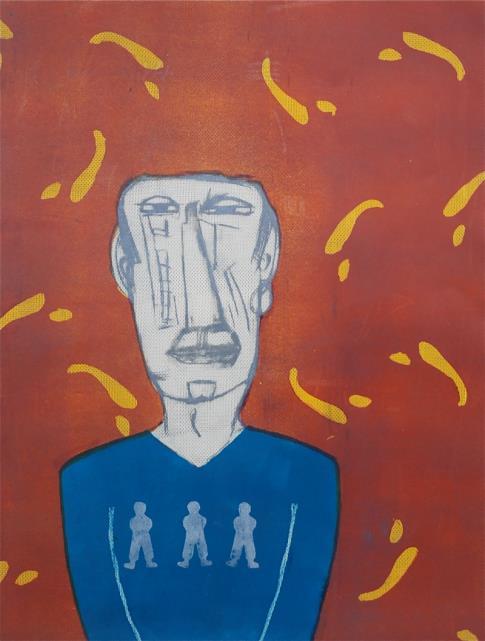

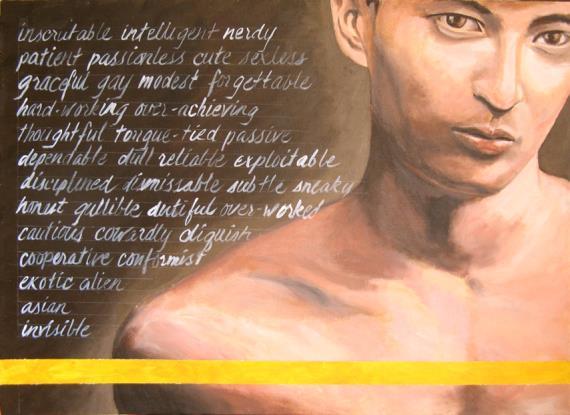

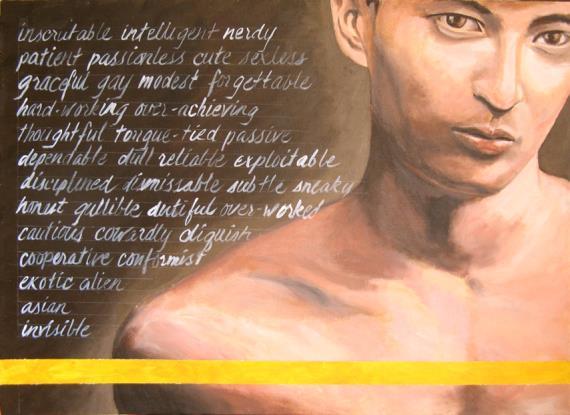

the following reason: it has been nearly 40 years since the publication of Berger’s Ways of Seeing, 30 years since Women Looking at Men, and almost 20 years since What She Wants and The Black Male. Much has changed within society, the art world, and theory, and Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze reflects these seismic changes. Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze is a much larger exhibition than its predecessors, with 117 artists participating in the gallery exhibition and an additional 89 artists included in the exhibition catalogue. The artists chosen come from a wide range of diverse backgrounds as do their male subjects, reflecting and representing a society that has become more diverse. Nonetheless, it is important to recognize that achieving diversity within both art institutions and society remains an elusive and incomplete process. As a reflection of contemporary society and culture, this exhibition is no exception despite the curatorial team’s best efforts. Much more work still needs to be done to overcome the very real and harmful effects of continuing negative stereotypes and bigotry. Shizue Seigel’s painting about how Asian men are still stereotyped and labeled, Scrutable (2011), makes this last point patently evident. Seigel juxtaposes a range of descriptive words with her sensitive portrayal of the head and shoulders of an Asian man. In so doing, she challenges the viewer to consider how reading certain words can influence seeing or “reading” Asian men’s bodies.

Included in Seigel’s list of words are both “gay” and “sexless,” signifying how Asian men have been historically viewed in American culture as sexually marginalized and desexualized. Performance artist Chanel Matsunami Govreau as her performance persona Queen Gidrea counters racist sexual stereotypes of Asian men with a blog called

Resexualize. In it Matsunami Govreau documents the research she has conducted in preparation for Hapa Bruthas (2011), her performance as a queer mixed race woman artist exploring representations of Asian American male sexuality in art and popular culture that was specially commissioned for Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze (www.resexualize.tumblr.com).

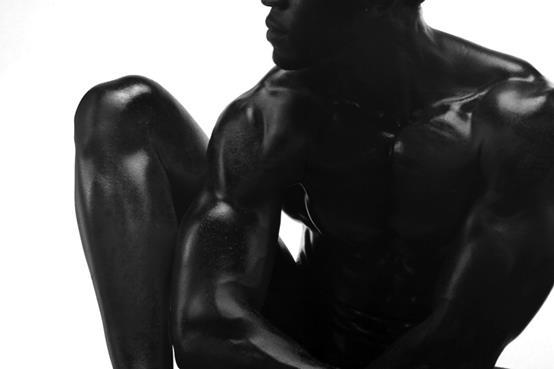

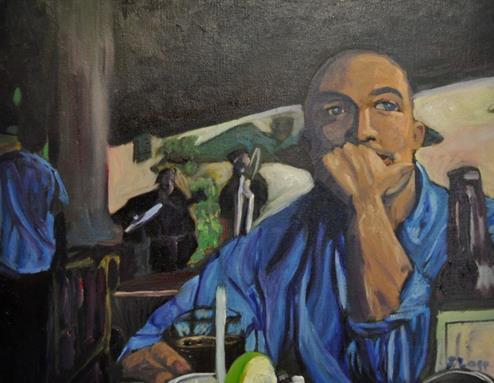

In contrast, African American, Latino, and working class men continue to be portrayed in mainstream visual culture as hypermasculine and/or oversexualized. A number of artists in the exhibition directly address these stereotypes. At first glance Annie Sprinkle may seem to reify racial stereotypes regarding black men’s penises with both her choice of title and model in Teeny Tiny Big Black Dick (1990). The viewer soon realizes, however, that the title is a provocation. Given the small size of the photograph, the viewer has to really, really want to look at the image to see it well. And to see it well, one has to look real close.

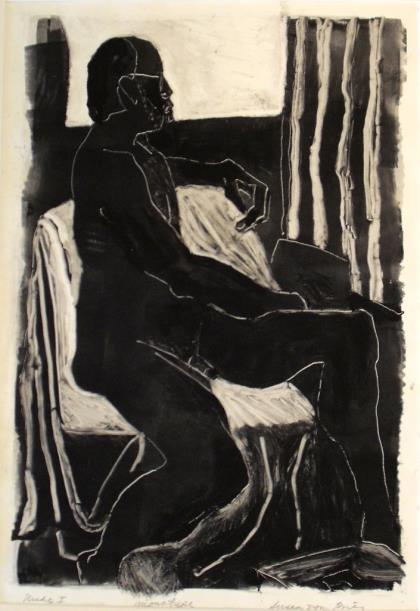

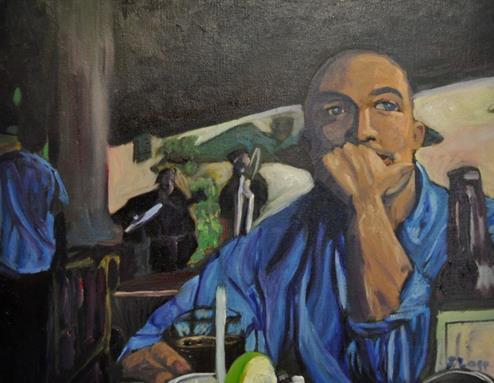

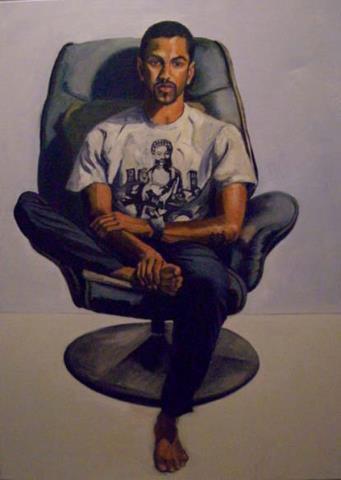

Once the viewer’s eye gets past the towering phallus in the foreground and the blatant symbolism of the erect Freudian cigar behind it, the viewer is confronted with the direct gaze of the male model, who is visibly struggling to raise his head in order to look at the camera. Teeny Tiny Big Black Dick dramatizes the black man’s struggles to make an interactive connection with the viewer by means of sexual display. Moreover, Sprinkle’s photograph makes visible his struggle for his subjectivity to be fully recognized as a unique individual, as well as his struggle to be regarded as more than just a body, symbol, or stereotype. Sal Sidner takes a different approach as she transforms negative stereotypes of African American men by offering an image of a contemplative young African American man with

19

Young Buddha (2009).

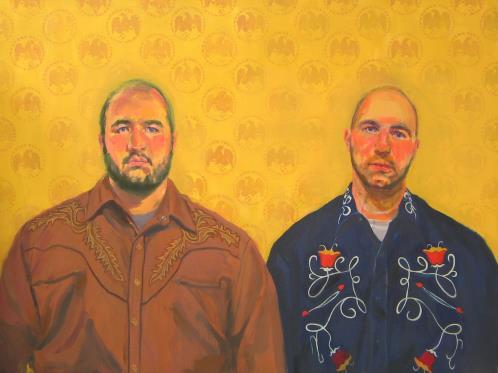

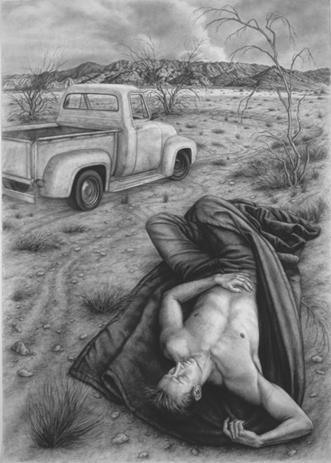

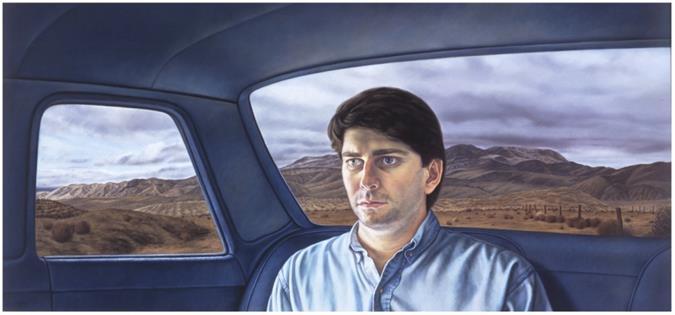

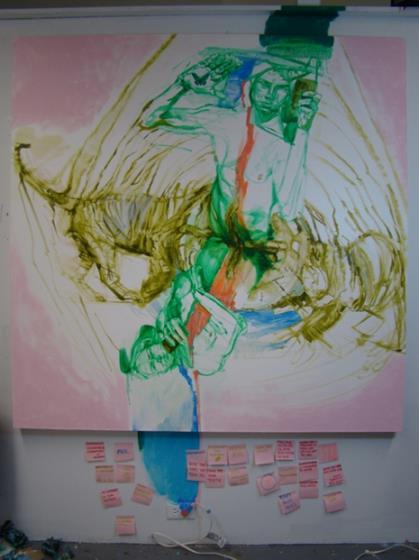

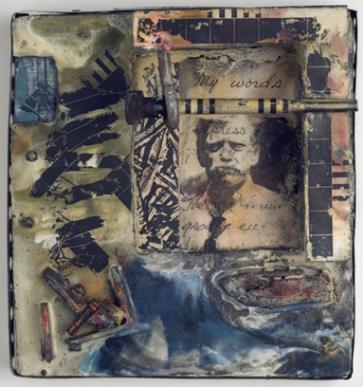

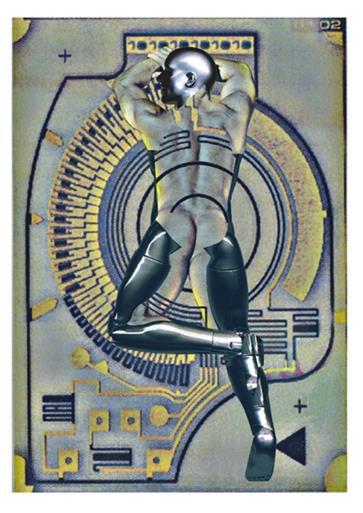

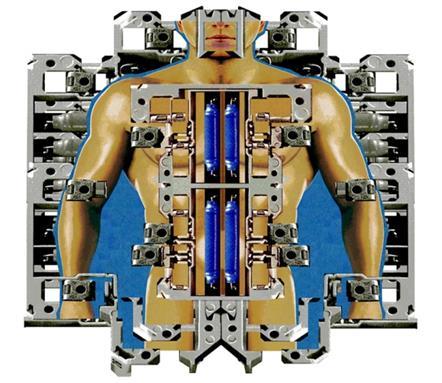

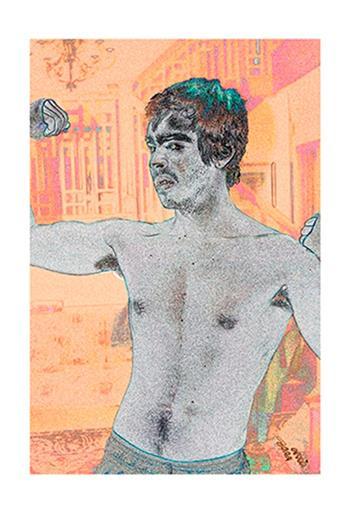

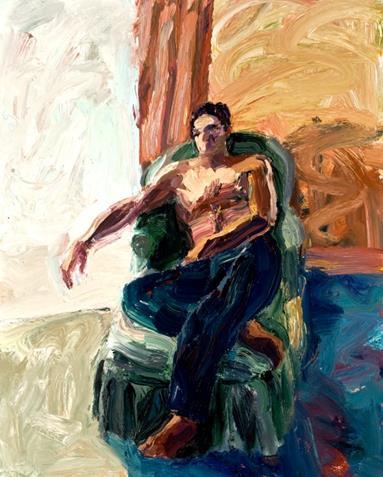

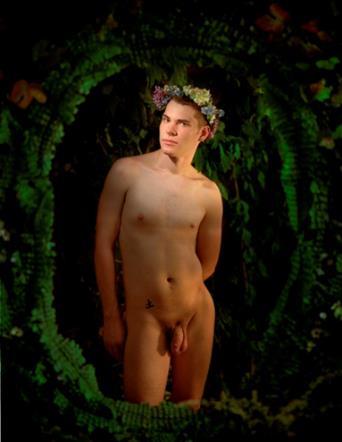

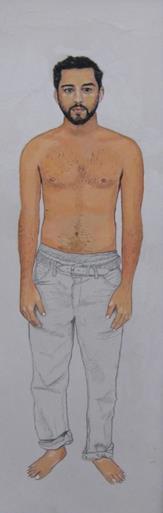

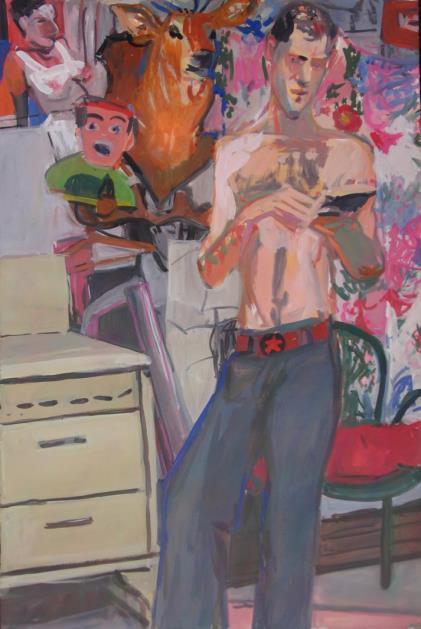

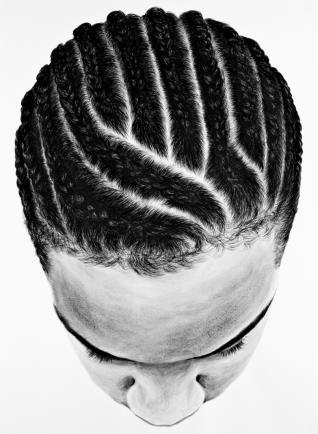

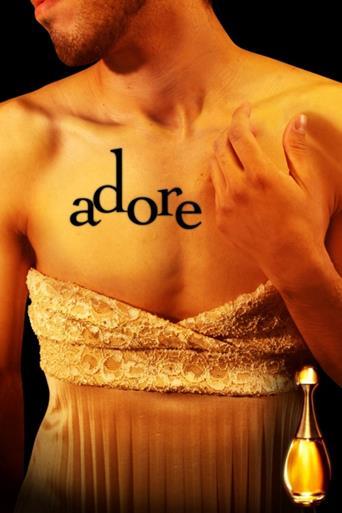

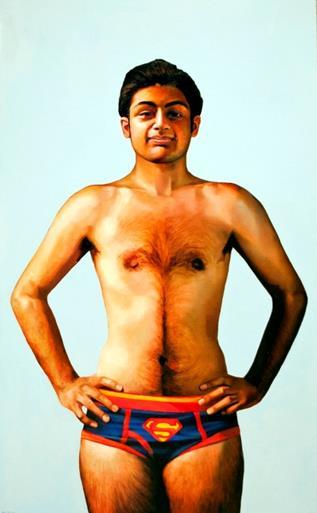

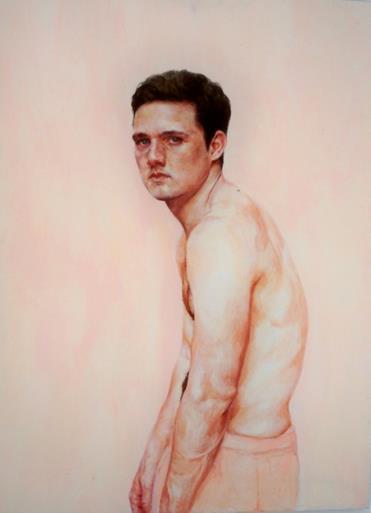

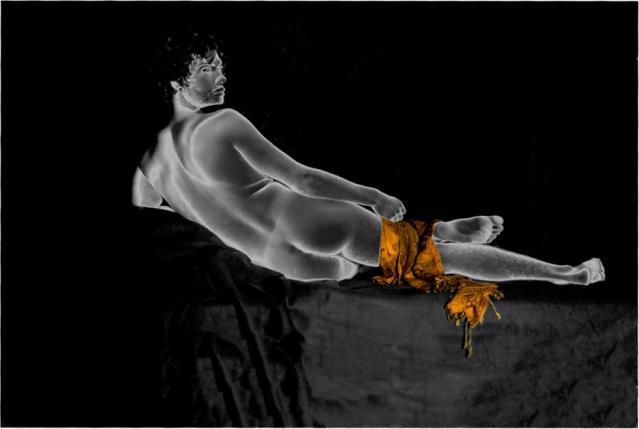

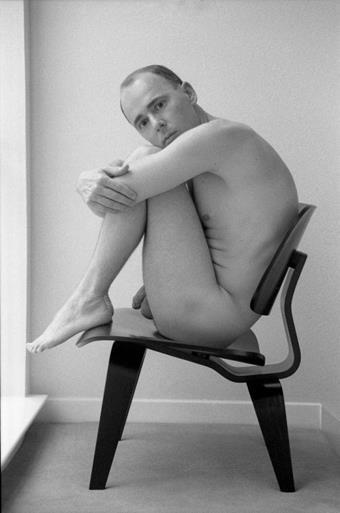

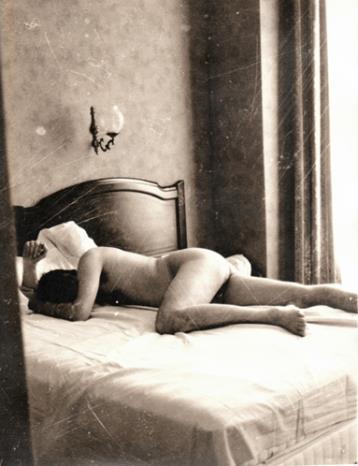

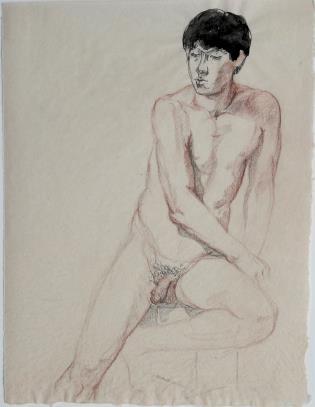

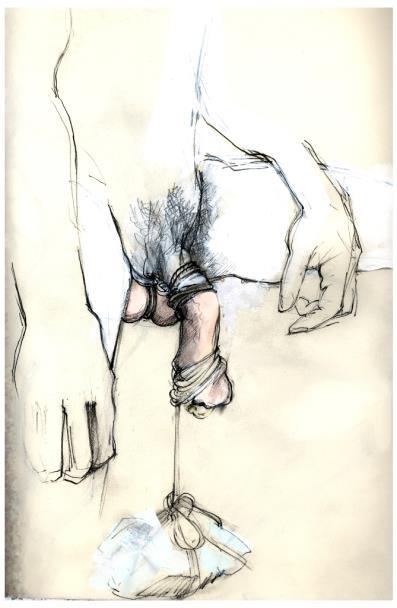

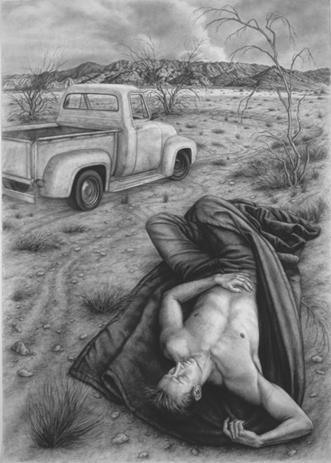

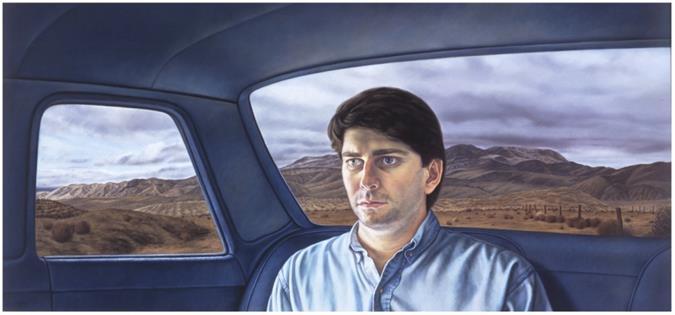

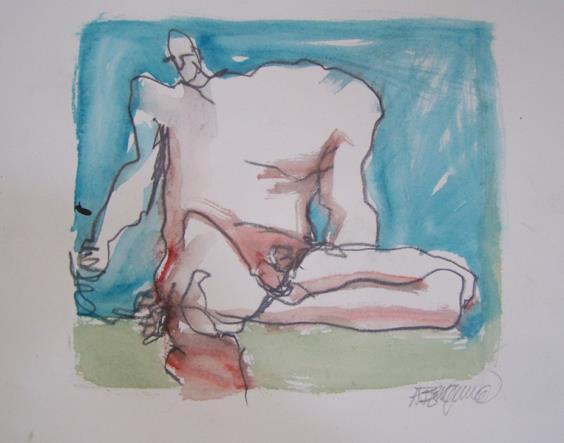

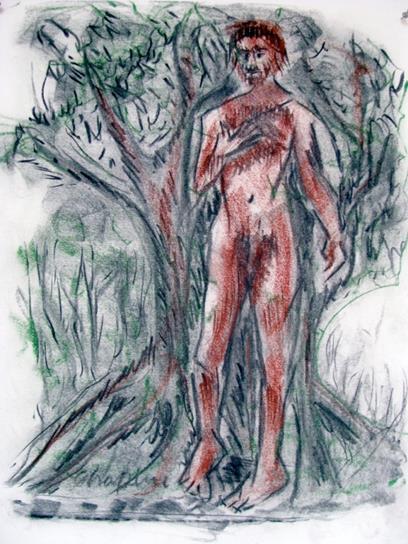

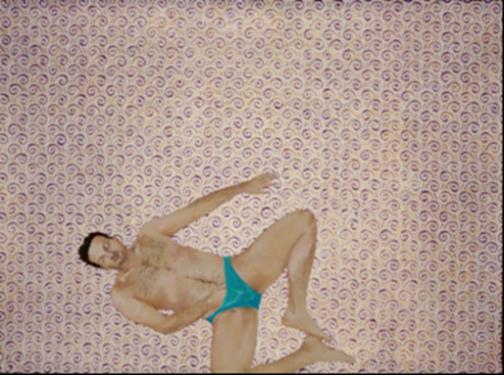

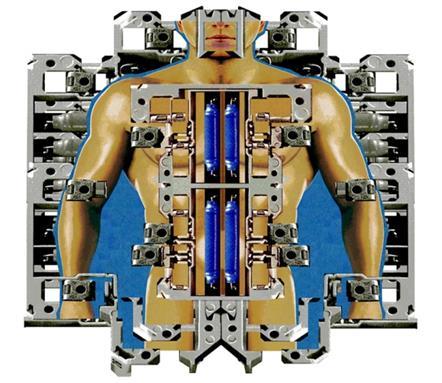

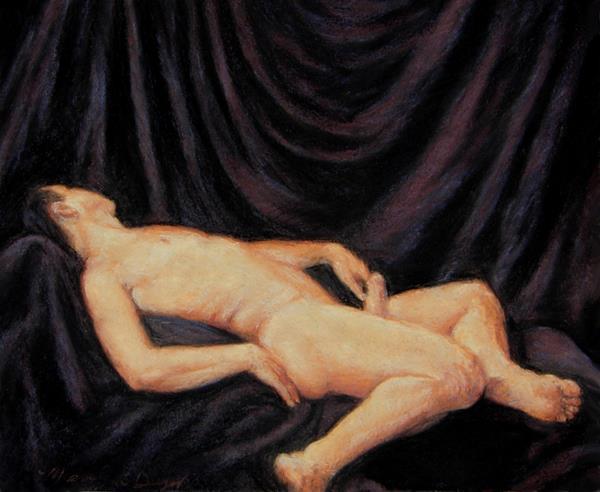

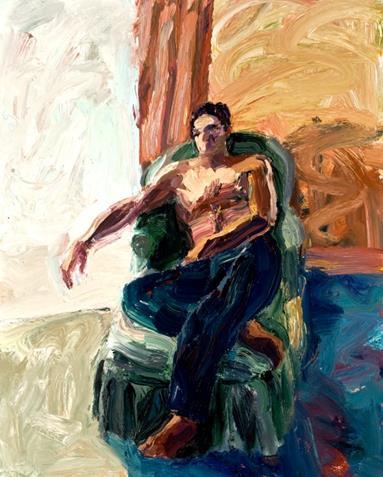

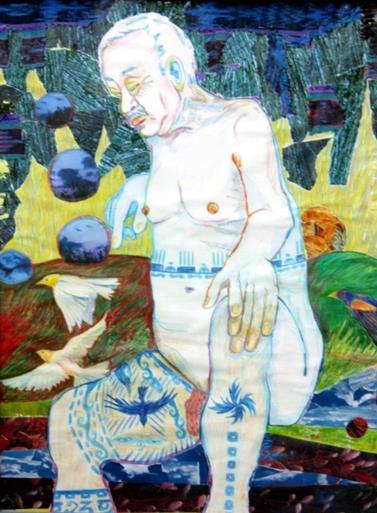

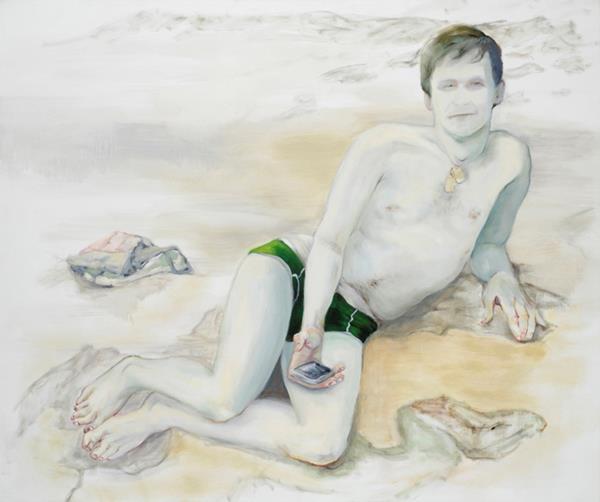

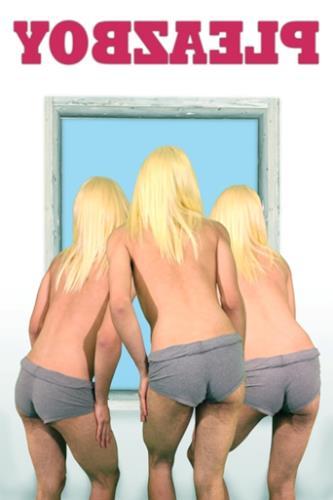

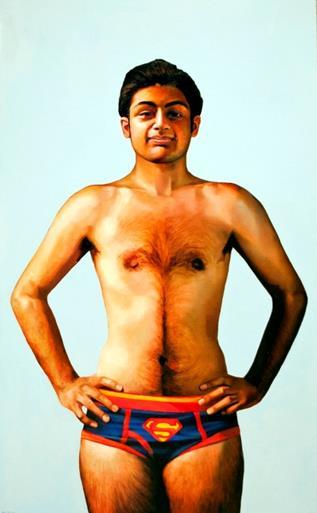

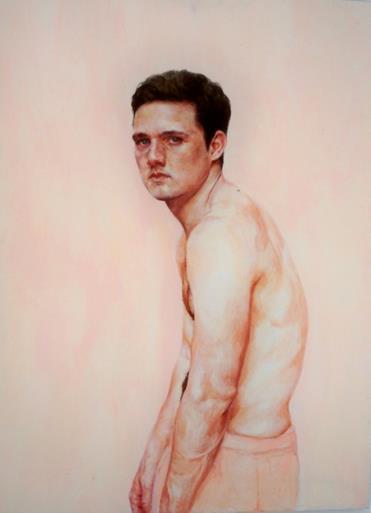

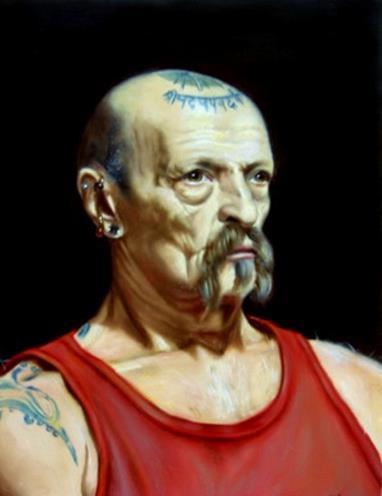

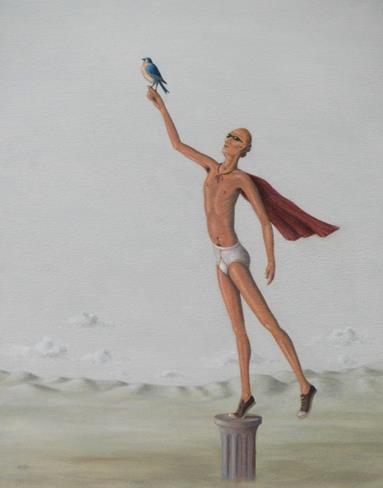

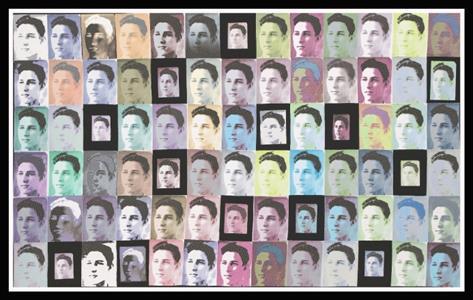

The commitment to inclusive diversity is also reflected in the type of artworks selected. Man as Object includes multiple art mediums such as painting, drawing, photography, video, performance, fabric art, sculpture, mixed media, collage, installation, conceptual art, assemblage, print, new media, and digital art. Multiple genres and styles within certain mediums such as painting and drawing are represented, as are remediations that are made in one visual medium to “refashion” works created in another.15 Photographic remediations of paintings include Laura Hartfold’s Graham Reclining (2004) and Eric With Flowers (2004), as well as Xian Mei Qiu’s Ophelia (2011), while Theresa Walloga’s painting Jeans Ad (2010) remediates photo advertising.

The Gaze, the Phallus, and Erotic Male Body Parts

Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze reflects the advancement of theory since the early 1970s— particularly theories regarding the gaze, the phallus, intertextuality, masculinities, and gender performativity. Berger’s assertions regarding the different ways men and women look paved the way for the theorization of the gaze within feminist film theory beginning with Laura Mulvey’s seminal essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” that was published in 1975. Mulvey expanded upon Berger’s ideas, drawing from psychoanalytic theories to assert “an active/passive heterosexual division of labor” controlling the narrative structure of film. For Mulvey, women are depicted as sexual objects intended for the male gaze, as spectacle, and as icons. Men are bearers of the look of the spectator, but “cannot bear the burden of sexual objectification.”16

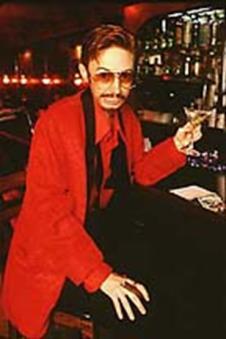

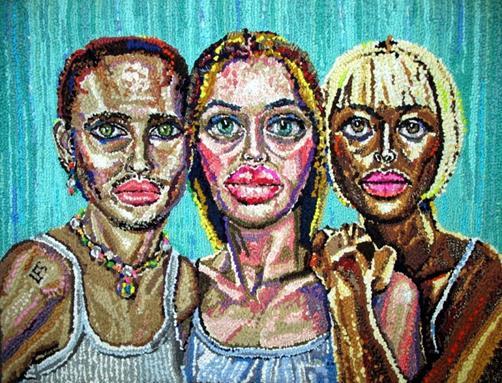

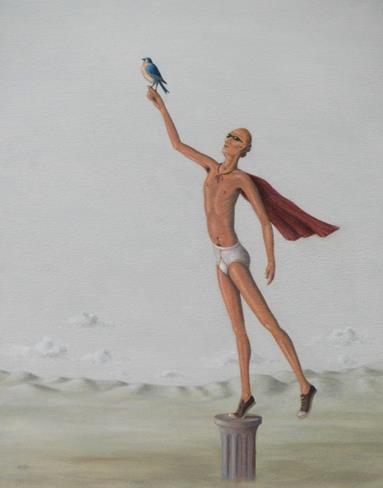

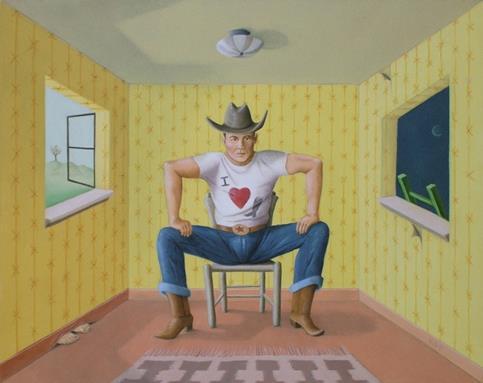

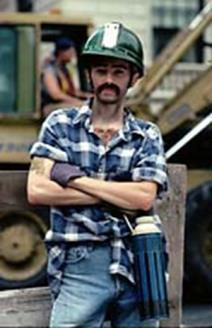

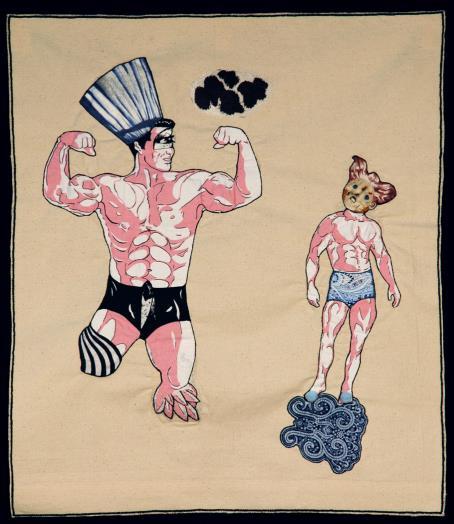

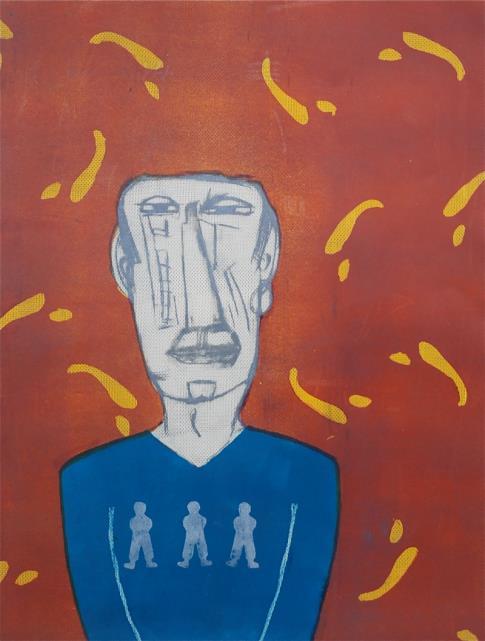

Mulvey’s essay became canonical in short order. In 1983 E. Ann Kaplan asked the question, “Is the gaze male?”17 and a whole bevy of articles has been written since asserting multiple alternative possibilities for male, female, racial, lesbian, queer, bisexual, and even “gaydar”18 gazes that link the act of looking with visual pleasure, which point to the hazards of attempting to create or maintain essentialist, singular, or even definitive categories regarding gender, racial, or sexual identities. Nevertheless, several artists in the exhibition depict the female heterosexual gaze in action: Clara Saprasa with her 2011 painting Object; Madelyn Smoak with her cat glasses-shaped jewelry pendant and chain, David and His Junk (2011); and Lynn Elliott Letterman’s lusty photograph Construction Guy (2010). Unlike film, which establishes the gaze through narrative, in these static images the active female gaze is made visible through the depiction of reflective lenses. We see the psychological impact of being looked at and exposed on three cowering men in Hazel Bartram-Birchenough’s painting Anatomic Series 1 (2010), while Karen Zack with Mankind 2 (2010) depicts three men whose exaggerated poses communicate their collective wish to be objectified.

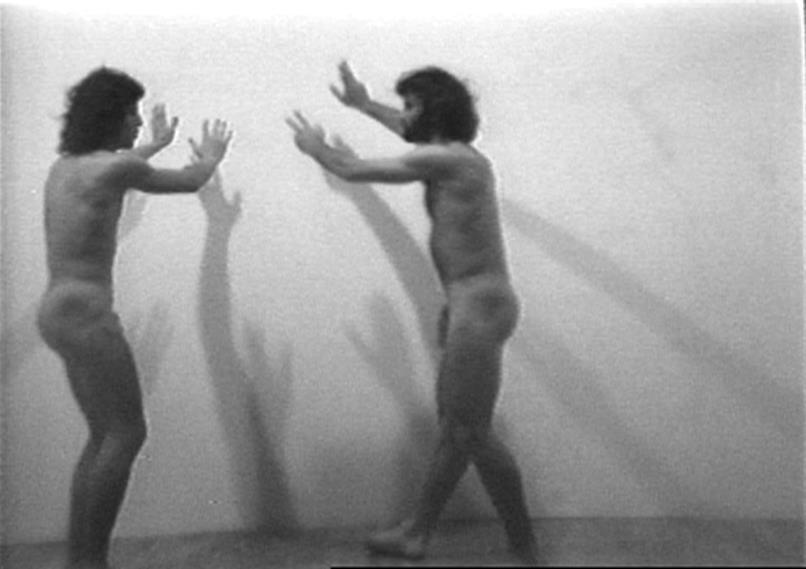

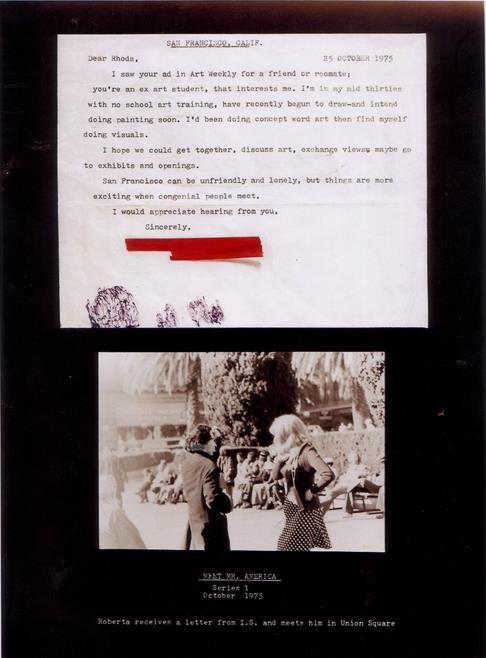

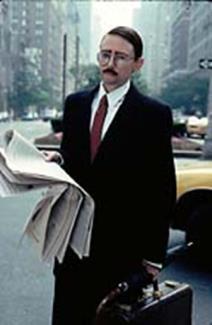

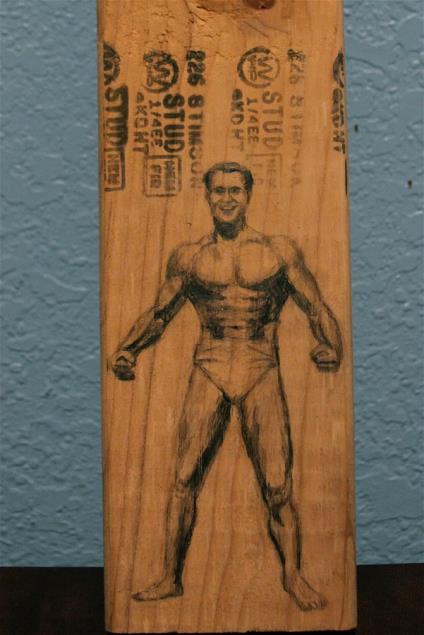

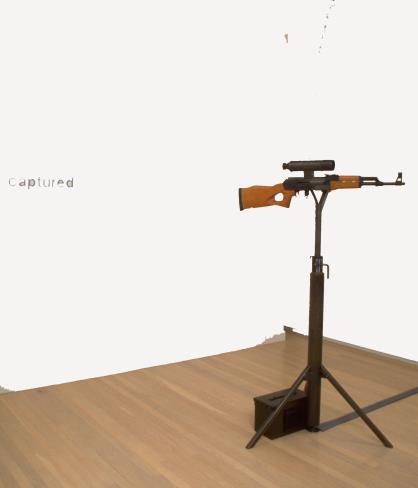

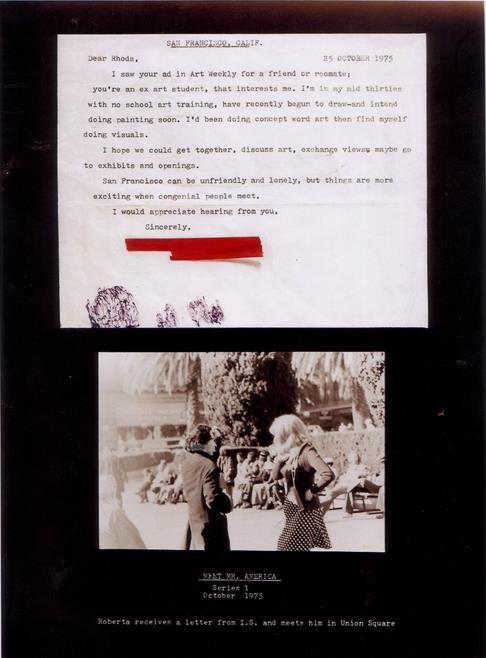

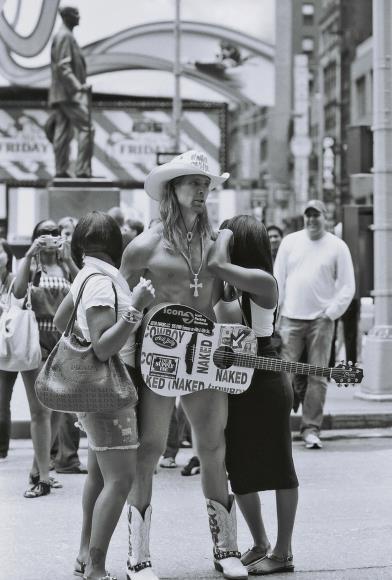

Looking at some of the art in this exhibition, I detect additional types of gazes. In Discipline and Punish the late philosopher Michel Foucault described the origins of technologies designed for the mechanisms of modern surveillance.19 We see how male surveillance of women can be surveilled from a distance with Lynn Hershman’s Robert Meets Mr. America Irwin-2 (1975) from her Meet Mr. America photographic series. As her fictional persona Roberta Breitmore Hershman met men who had answered Roberta’s personal ads with letters. The meetings were secretly documented, exposing the behavior of

20

men during such awkward first face-to-face encounters. Hershman demonstrates various techniques by which women can reverse the male gaze and dismantle its more pernicious effects: by transferring its usual setting from the private sphere into the public realm, by exposing and documenting it with surveillance technologies, and perhaps most empowering for women, by taking complete control of the conditions in which it takes place. Such methodologies have served Hershman well as a feminist filmmaker and director, which she points out in the text she wrote specifically for this catalogue; “Complicit Object—Reversing the Gaze.”

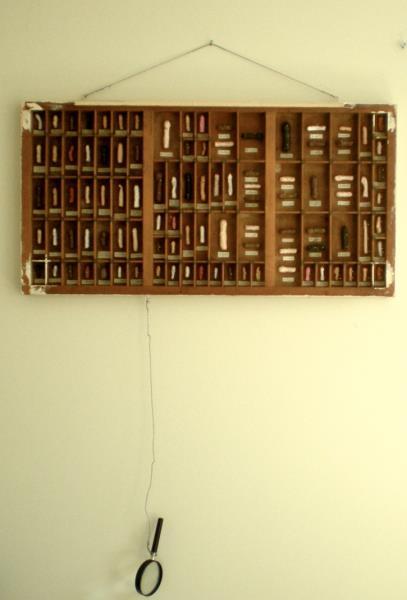

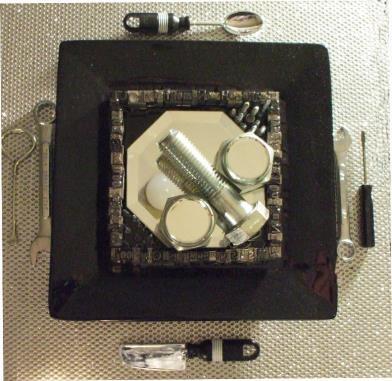

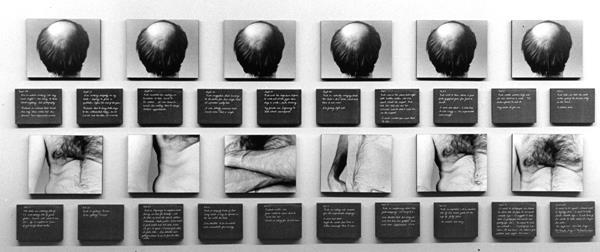

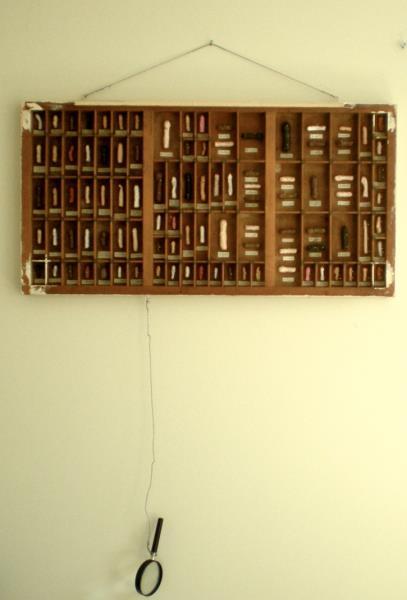

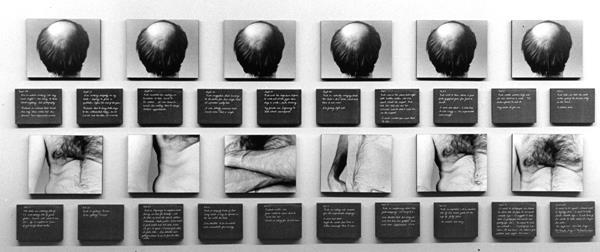

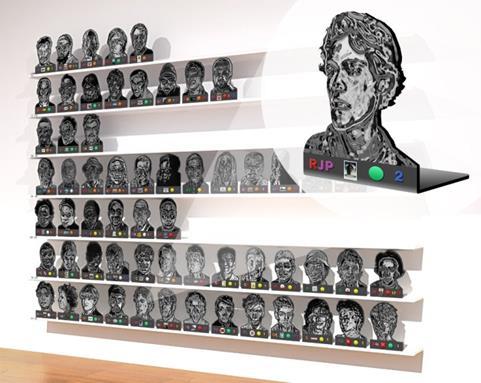

Foucault also wrote on medical, clinical, and scientific gazes while also tracing the rise of both the medical clinic and the scientific study of sex, which he called scientia sexualis. 21 Carolee Schneemann takes on the scientific gaze with her own sexological survey based on 40 actual sexual encounters and charts her “findings” in Sexual Parameters (1971). Schneemann asserts the importance of learning from one’s own experiences even appropriating scientific methods. Thus she records more than frequency, duration, and penis size; she documents subjective qualities such as emotions, impressions and memories to give a more holistic profile of each lover. J. Toffic alludes to a scientific gaze that predates modern science the tradition within natural history of collecting and classifying artifacts. With The Collector (2010) Toffic spoofs traditional cabinets of curiosities with a tongue-in-cheek collection of penis specimens.

Given that cabinets of curiosities were also found in ethnographic and anthropological museums, the feminist interrogation of additional “objective” gazes can be observed with Toffic’s The Collector, particularly the ethnographic gaze, the colonial gaze,

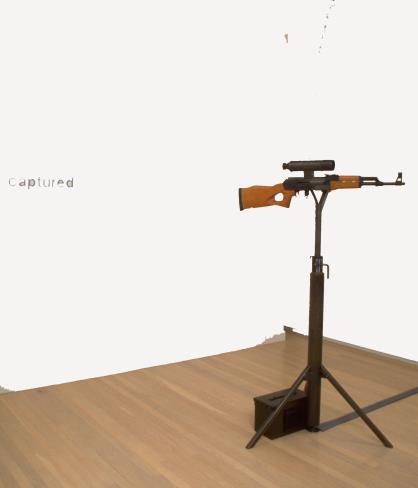

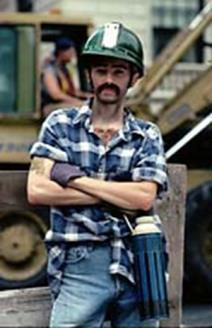

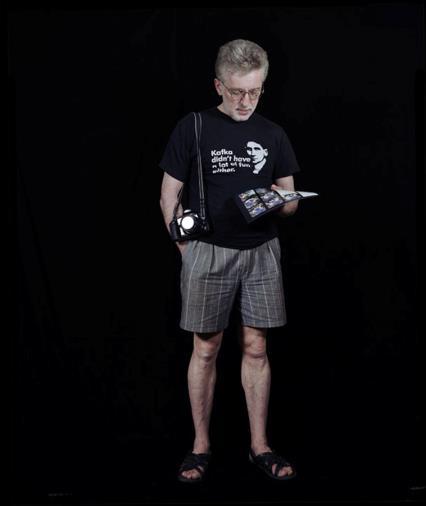

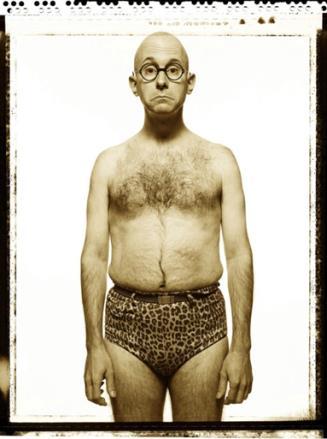

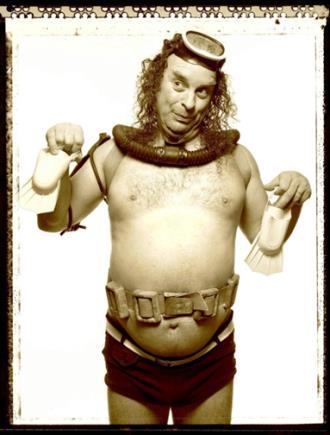

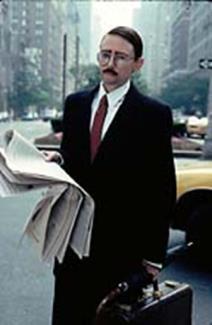

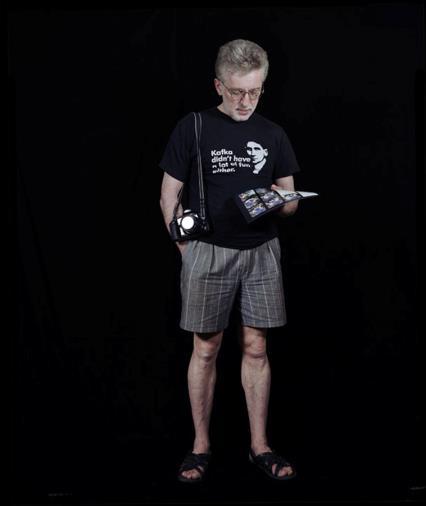

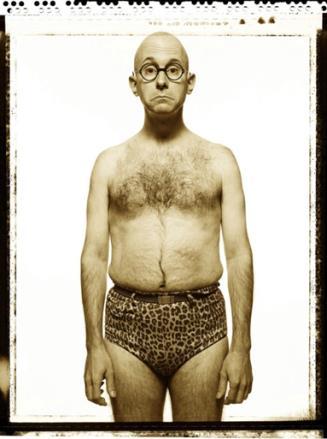

and the imperialist gaze. Tamarra Kaida overtly satirizes “studies” of two different male occupational “types:” Dan Noel (Scholar/Writer) (1999) and Russian Photographer with Contact Sheet (1999). In contrast, Alexandra Walker’s photographic studies Driver (2011), Resting (2011), and Jacob (2011) seem to blur ethnographic study of working class white men with the tradition of social documentary photography. What are we to make of Jacob’s creepy stare, let alone his gun?

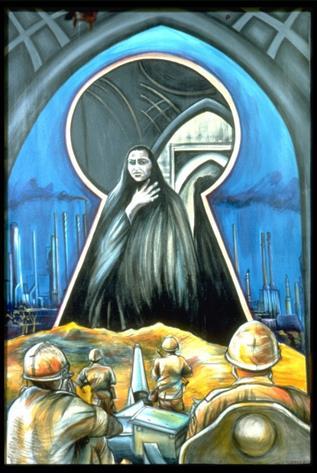

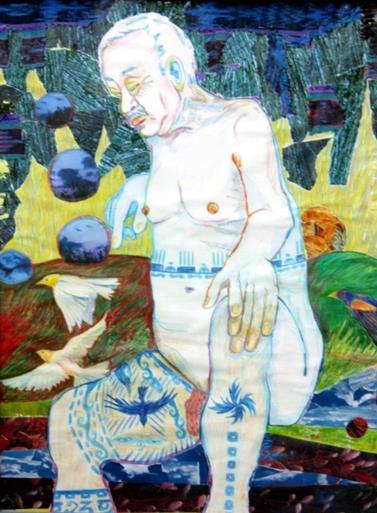

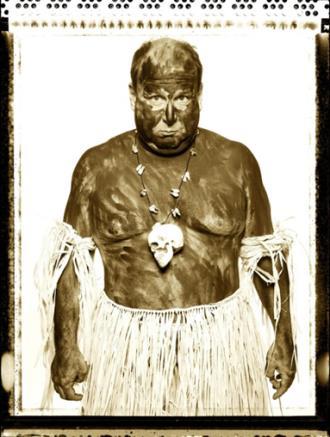

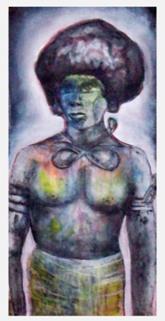

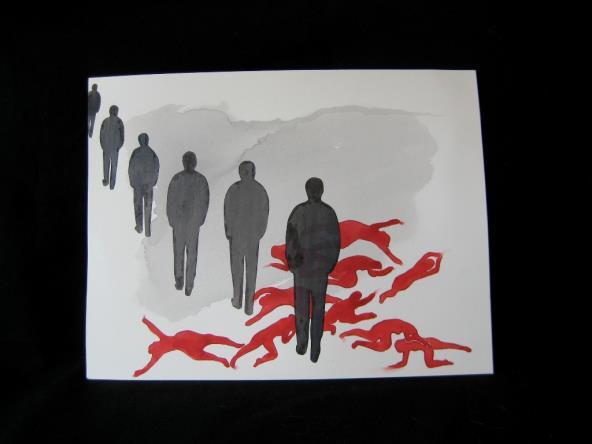

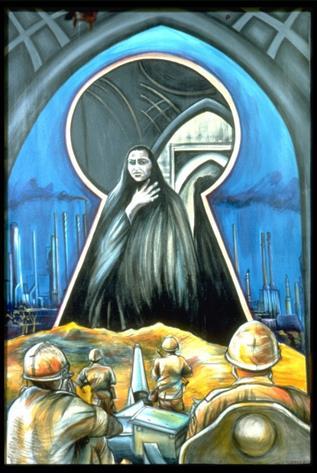

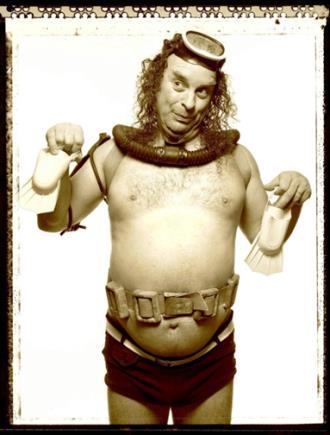

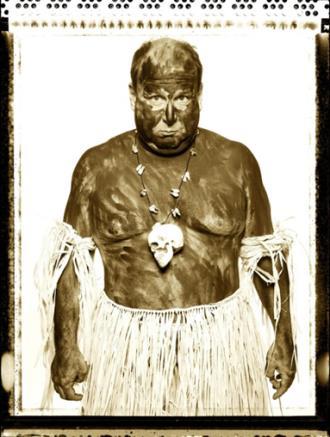

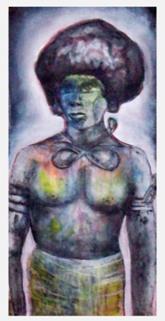

Other works such as Amelia Lewis’s 2010 painting Tribesman (Native), Heather Pilapil’s painting Errol (2004), and Juana Alicia’s painting Citizen (1998) defy ethnographic gaze’s tendency to degrade its subjects into exotic “others” in attempt to document or “study” them. Indeed, some works in the exhibition endeavor to dismantle the ethnographic gaze altogether. For example, Allison Leach’s photographs Sexy Beast (2008), Jacques Cluelez (2008), and Shy Savage (2008) are scathing in their mockery of white man’s sense of entitlement, which in the artist’s own words, “examines the hubris of Western exploration.” Pallavi Govindnathan questions gender presumptions of the colonial/imperial gaze with her photograph, Historical Inequality (2011) as does Juana Alicia with her striking painting, The War Voyeurs (1991). Juana Alicia’s painting records a specific historical moment: the First Gulf War in 1990. Her depiction of an Iraqi woman returning the gaze of American soldiers captures what has usually been found missing in history: women’s perspectives. Juana Alicia deconstructs male imperialist and militaristic gazes by reflecting them back through the eyes of the Iraqi woman. Julie Sutherland addresses another tendency of history’s purview: the minimalization of women’s contributions. Sutherland makes visible the old adage “Behind every great man

21

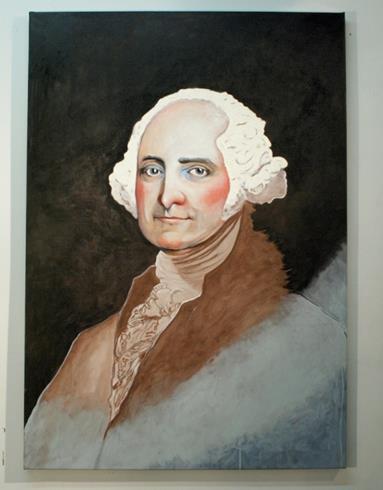

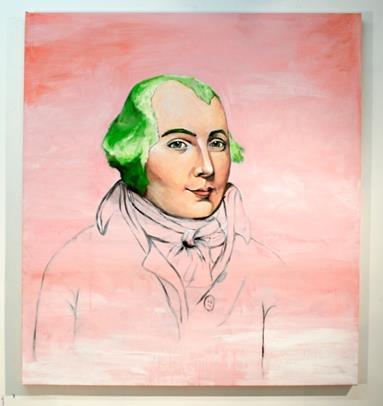

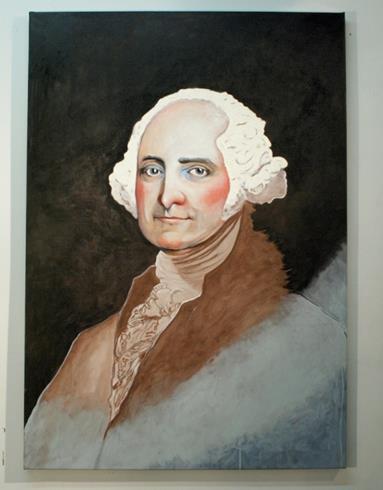

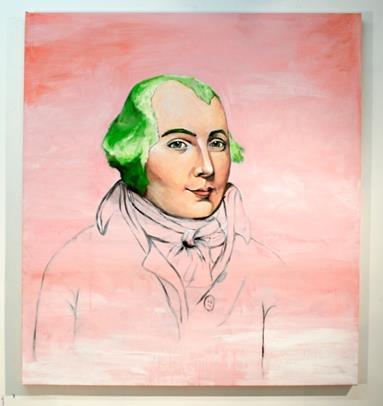

is a woman” with her historical/herstorical paintings, Marthageorge Washington (2010) and Dollyjames Madison (2010).

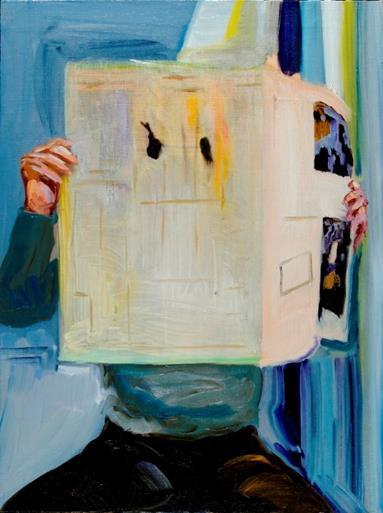

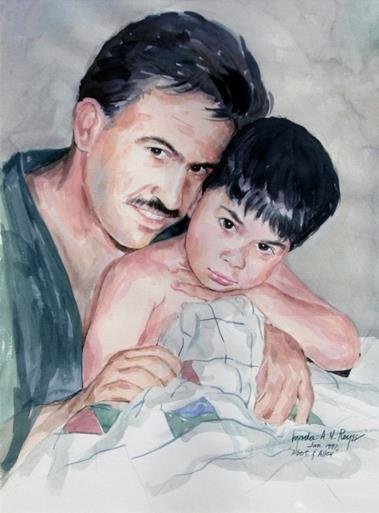

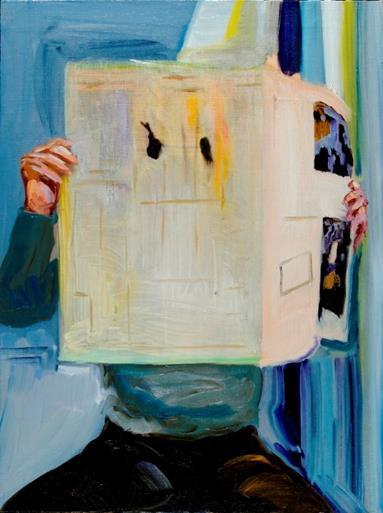

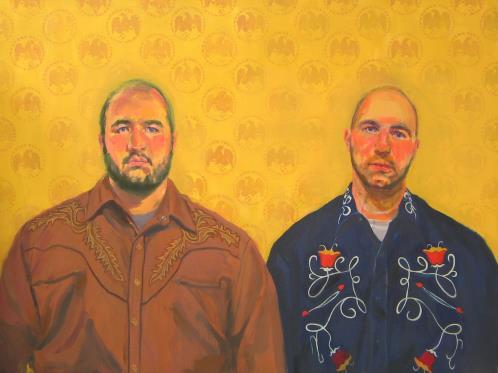

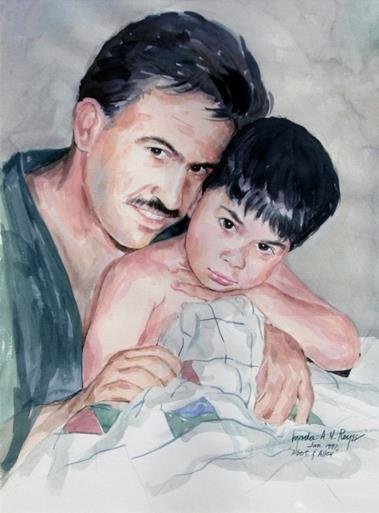

The results of what I would call “familial gazes” and domestic gazes can also be seen throughout the exhibition. We see the daughter’s loving filial gaze at work with Bonnie J. Smith’s DAD (2008) and Reena Burton’s Papa (2007). Christina Renfer Vogel scrutinizes family resemblances between her male siblings in Portrait of Two Brothers (2008). Lynda A. N. Reyes highlights the close ties between Albert and Allen, presumably from the mother/wife’s conflated perspective in Father and Son (1997). Juana Alicia’s Corazón de Melon (2009) asserts an erotic, loving and deeply appreciative “marital” gaze, as does Jasmine Begeski’s photograph of her reclining husband, Lay (2009), which along with Window (2009) and In Hand (2009) documents the couple’s struggle with infertility. Amy-Elyse Neer’s The Affair (2009) and Mette Tommerup’s Newspaper (2010) illustrate that the marital gaze can be imbued with ambivalence,

critique, and even contempt.

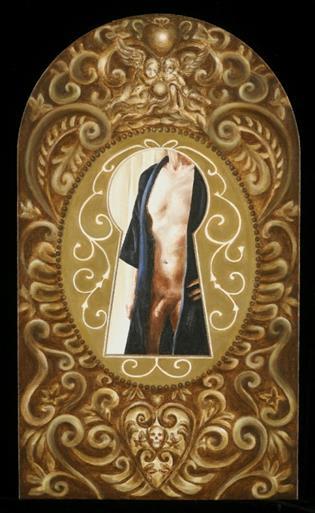

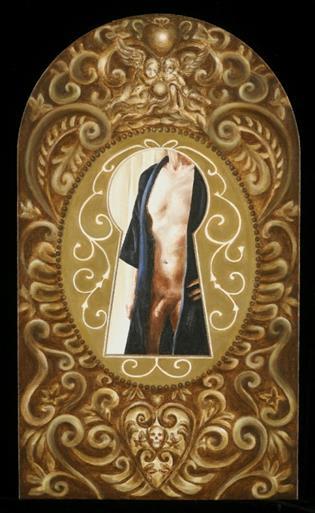

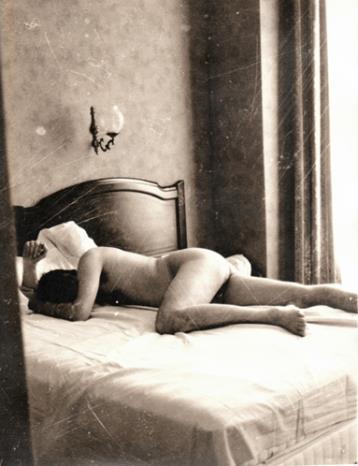

As already indicated, gazes can be multiple, hybrid, overlapping, ambiguous, ambivalent, and even paradoxical as they reflect the viewer’s positioning(s) at any given point of time. Female gazes as erotic gazes remains paramount in Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze. Men are depicted as objects of desire, fantasy figures, lovers, partners, and husbands, which can help explain why the female heterosexual erotic gaze at times coincides with, and differs from, gay male gazes. The erotic gaze irrespective of sexual preference with its scopophilliac pleasures often leads to voyeurism. In her painting Victorian Keyhole (2011) Sharon Leong’s painting both aestheticizes and thematizes voyeurism of men with ornamental flourish.

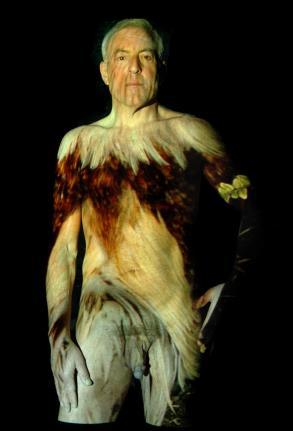

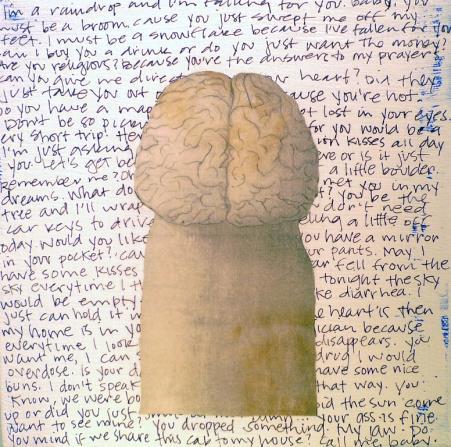

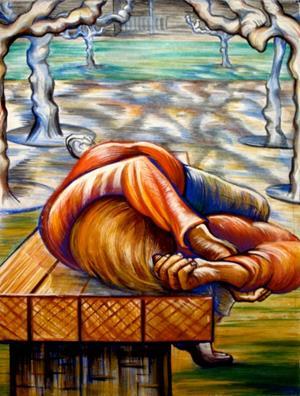

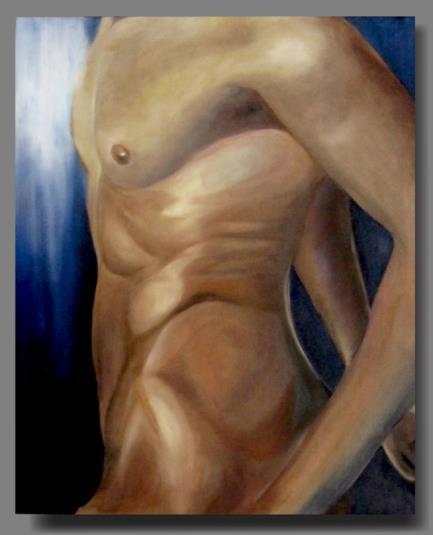

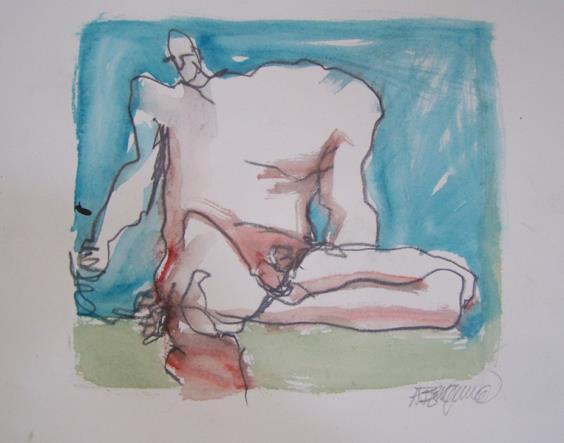

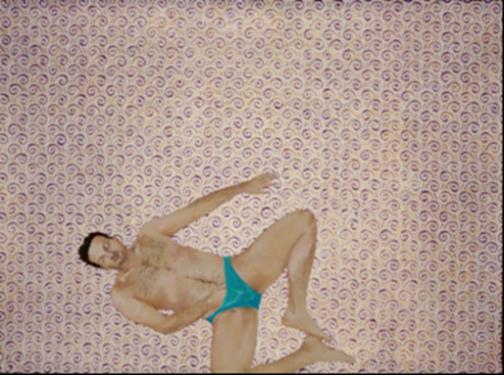

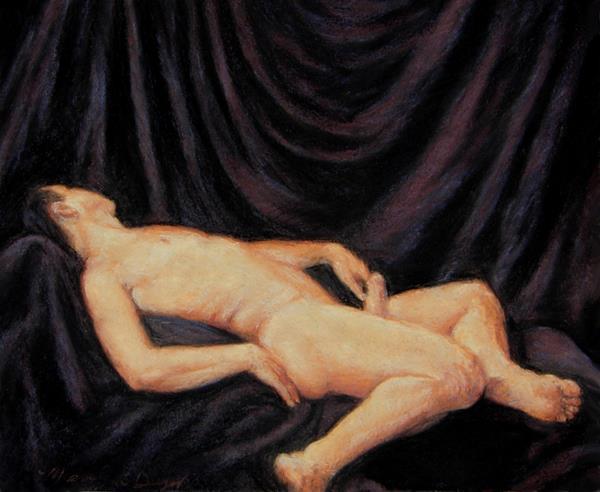

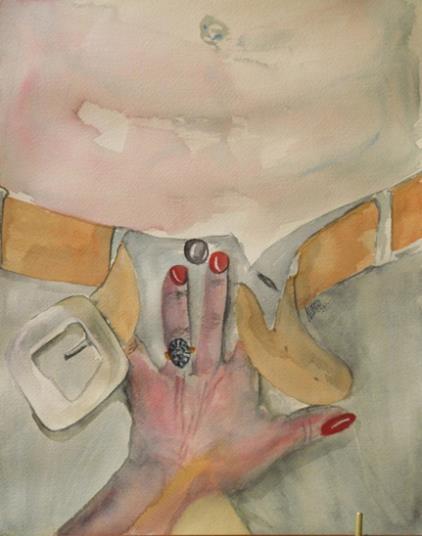

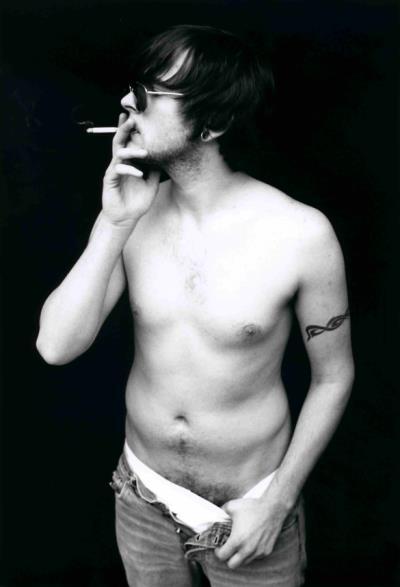

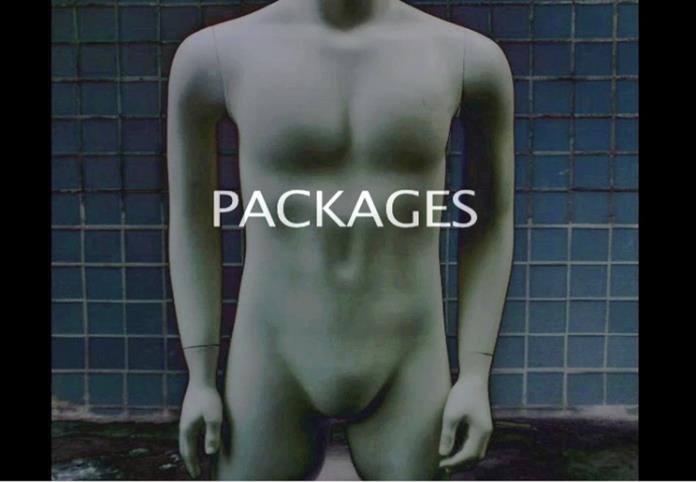

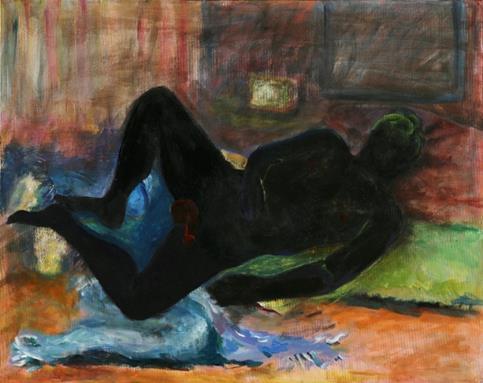

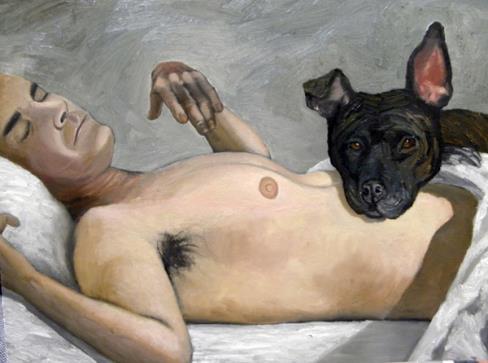

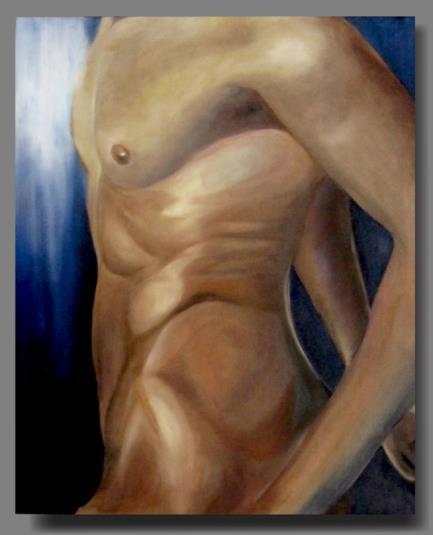

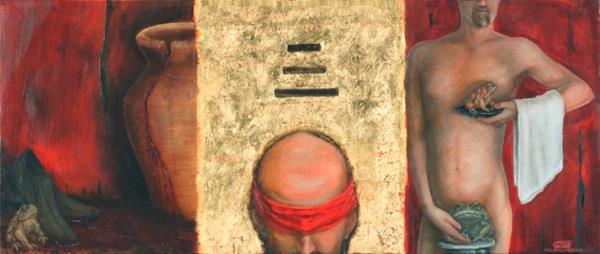

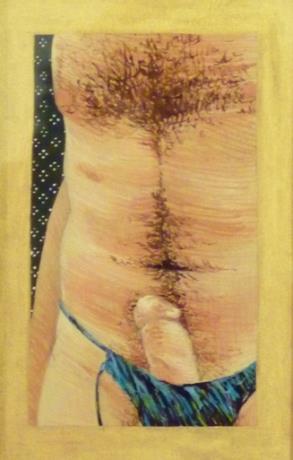

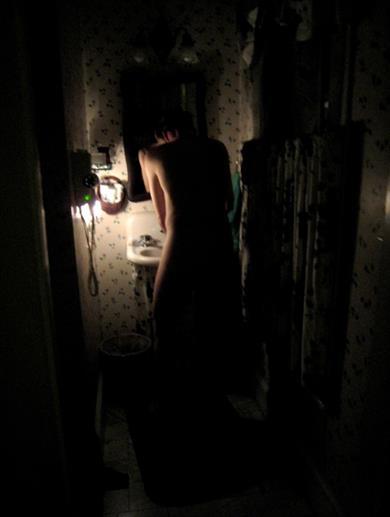

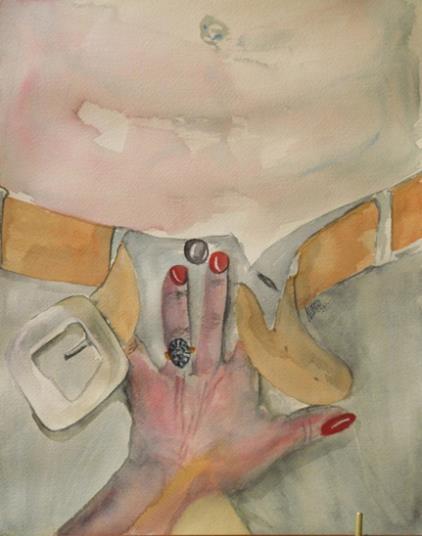

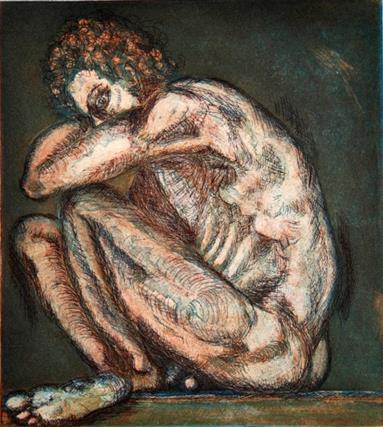

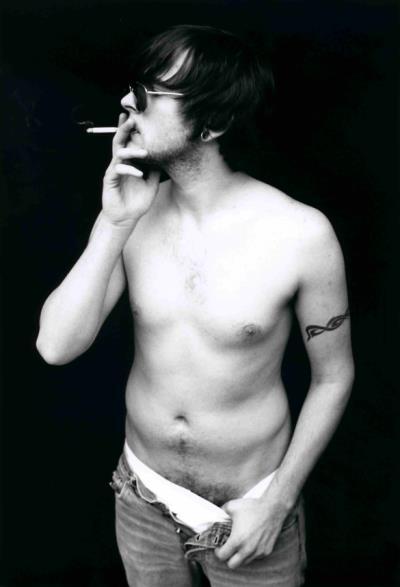

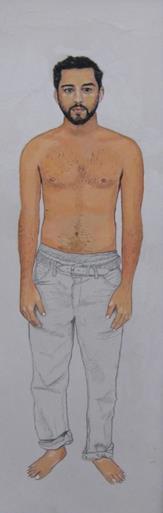

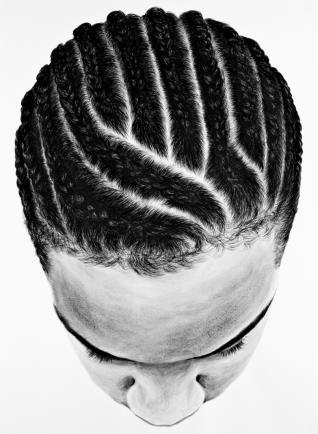

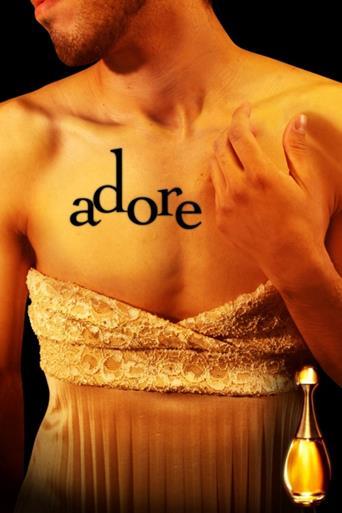

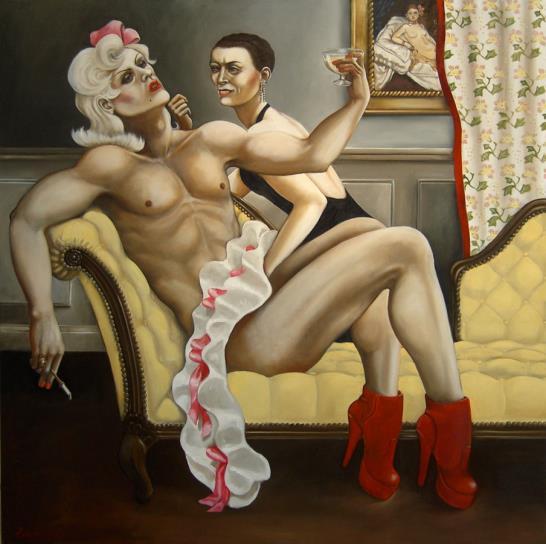

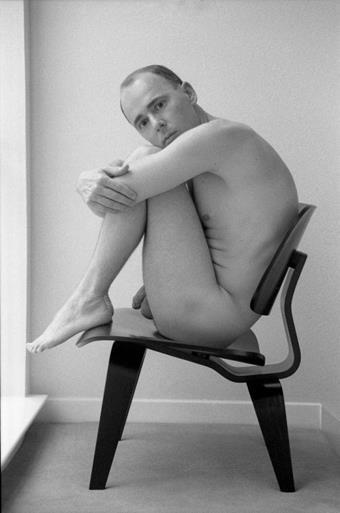

The erotic gaze also leads to fetishism. I leave aside feminist debates over the utility of classic psychoanalytic theories of the fetish for women due to the fact that many of the artists of Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze zero in on the erotic qualities of particular male body parts. Sheila Winner with Unbuttoned (2011), Sita Mae with The Triumph (2008), and Mel Ahlborn with Cathouse-Appetizer (2011) accentuate alluring qualities of the male torso and chest. As part of a series, Cathouse-Appetizer needs to be considered with another view of the male torso, Cathouse-Entrée (2011), and Cathouse-Dessert (2011), which provides a frontal view of a semi-reclining male nude’s body.

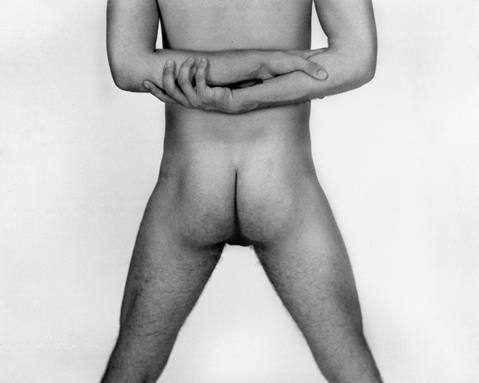

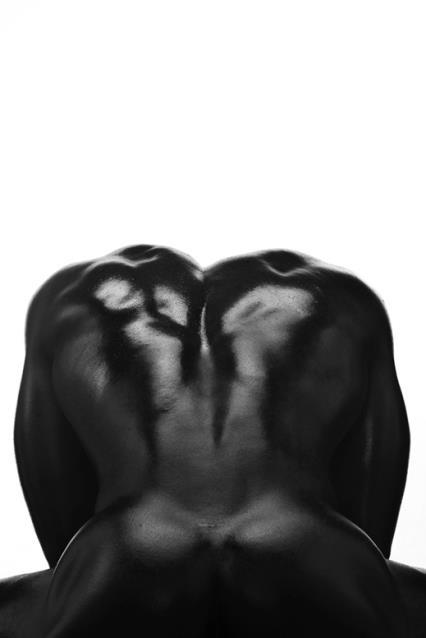

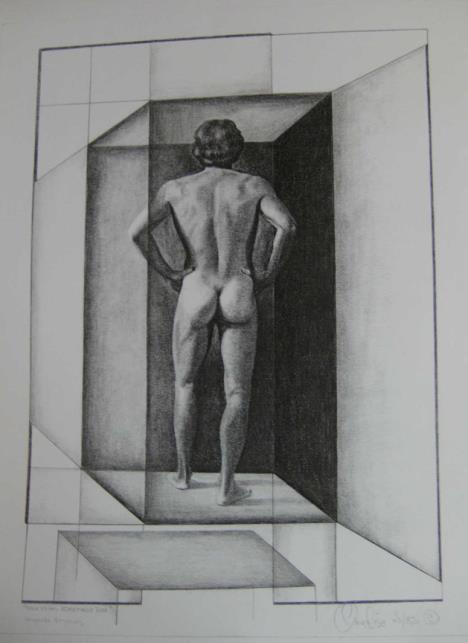

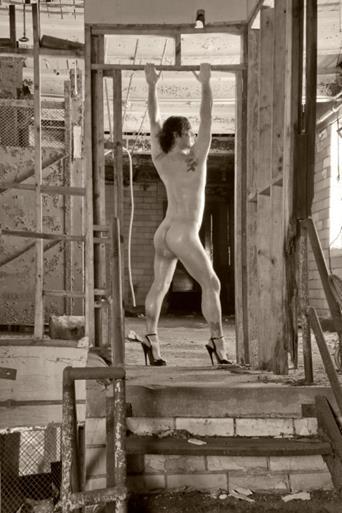

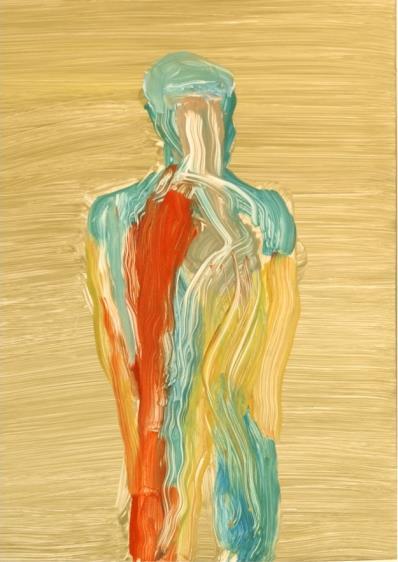

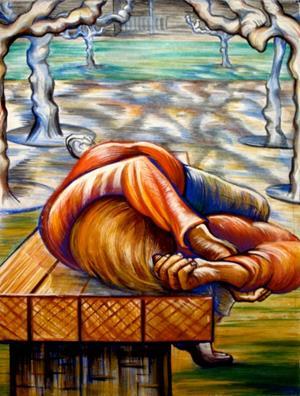

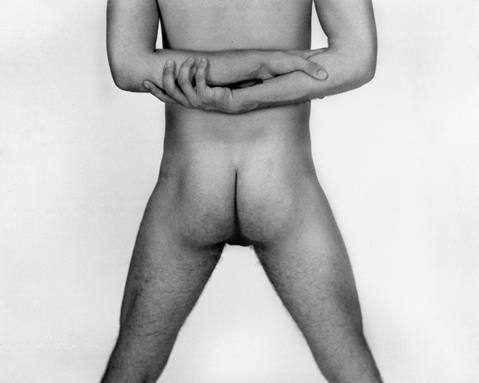

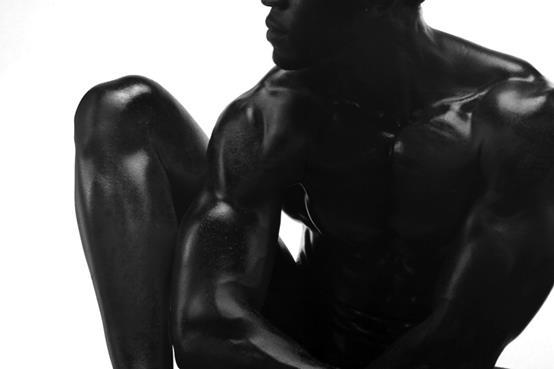

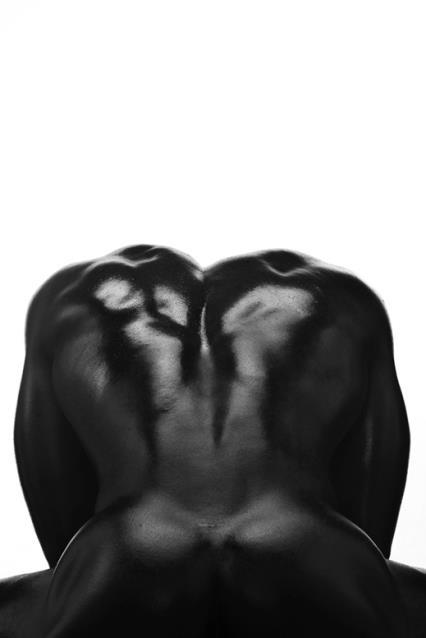

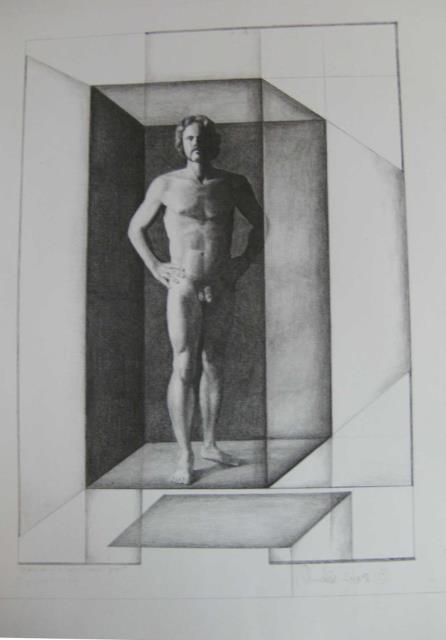

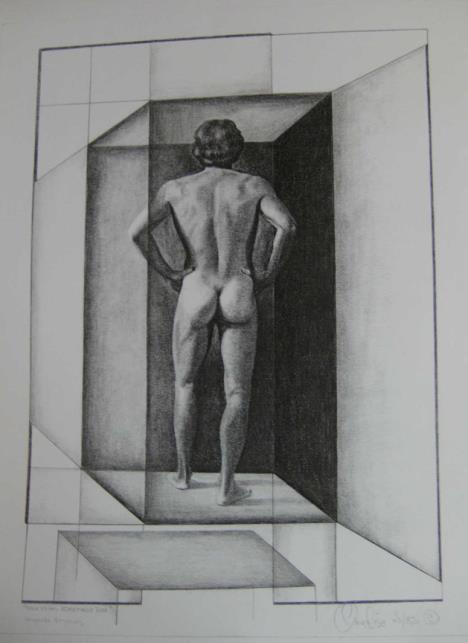

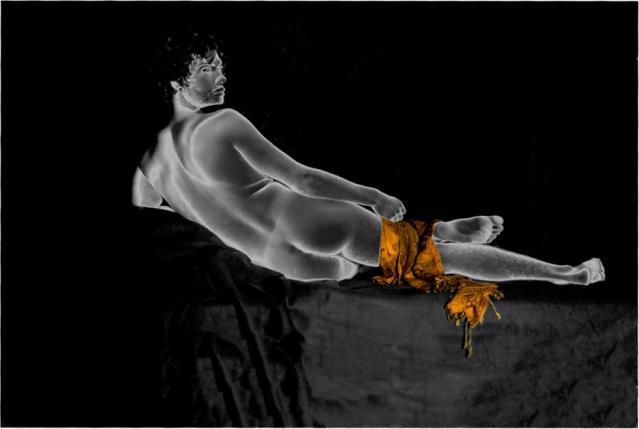

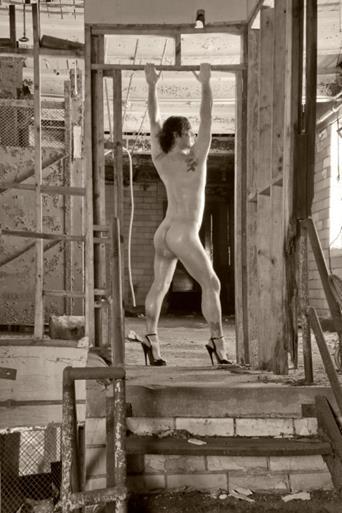

Moreover, Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze features a panoply of sensuous rear views of men and alluring images of male backsides. These include Janice Nesser’s climbling out of the white (2008), Marlene Hawthorne Thomas’s Untitled (From the Study of Man Series) (2009), Nicole Craine’s Untitled Nude (2010), Lorena Sanguiliano’s Body Builder I (2010), Trix Rosen’s Beyond XY: Inside the Abandoned Falstaff Brewery, No. 2 (2010), Sara Hopkins’s Turn Over (2010), and Annelise Jarvis-Hansen, The Beautiful Hu-Man (2010). The male butt in Della Calfee’s Ass Like That (1992) affirms traditional Kantian aesthetics’ emphasis on symmetry for beauty more specifically, its symmetry between between convex and concave forms as well as between light and dark shadows. Yet traditional Kantian aesthetics alone doesn’t seem to explain completely why it strikes the viewer to use the vernacular as one hot piece of ass. Could it be that those pinchable butt cheeks have something to do with it?

As mentioned previously, a considerable amount of erotic and critical attention in the exhibition focuses

22

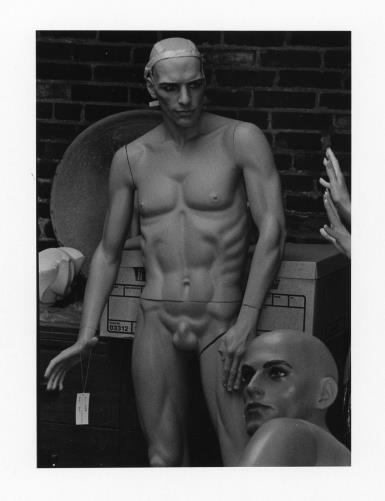

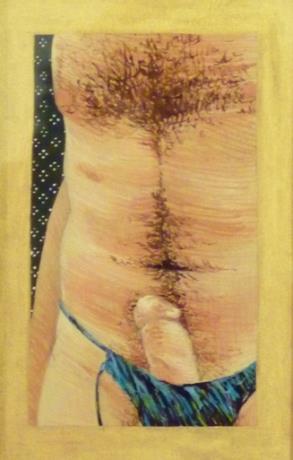

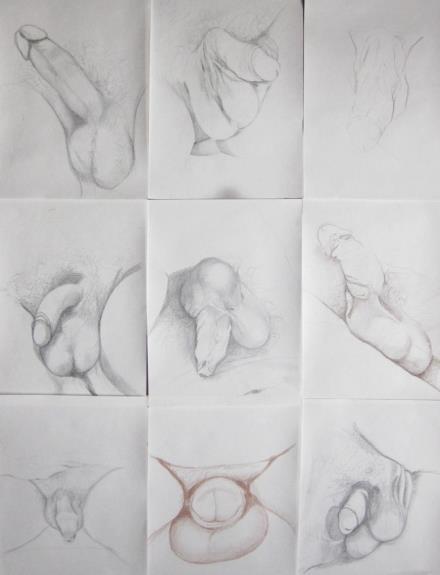

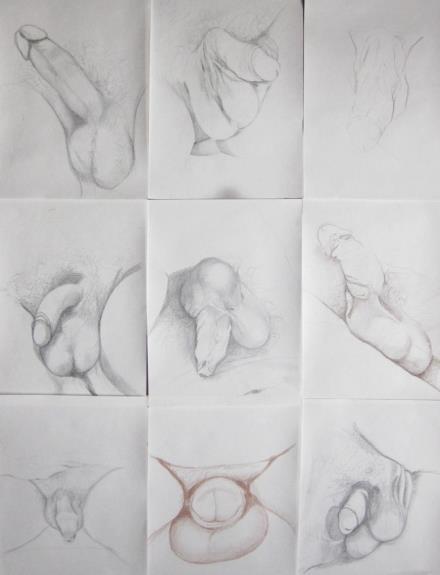

on the penis and the phallus. The visual display of actual penises particularly non-erect penises is rare, given that no real penis can ever live up to what Richard Dyer has called “the mystique implied by the phallus.20 We are left with a lingering question: is a visual representation of a penis ever just a representation of a penis? Carla Sanders’s array of drawn penises in 9 Cocks (2010) seems innocent enough—until the viewer starts making comparisons. Michelle Lopez offers close up views of penises and scrotums with her black and white photographs without much commentary. With Lopez’s Male Nude #1 (2010) the viewer sees a flaccid penis from an unusual side angle that makes it appear almost flat. The singularity of such an image, I think, speaks volumes. Both Judy Johnson-William’s With Hoodie (2011) and Nanette Wylde’s Pinkie (1992) provide examinations of penis tips. Such close observations allude to, as well as counter, the prevalence of “pink and open” shots of female genitalia in mainstream pornography beginning with Larry Flynt’s Hustler magazine, while their use of diminutive names for their titles calls attention to the wide-spread use of slang terms for female anatomy.

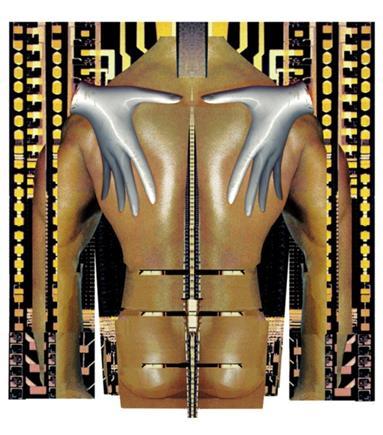

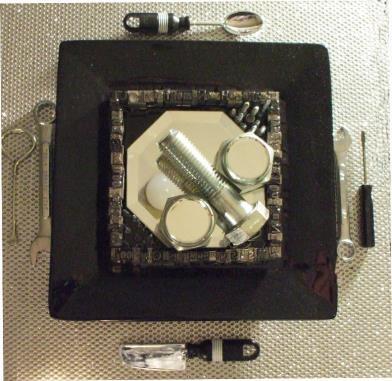

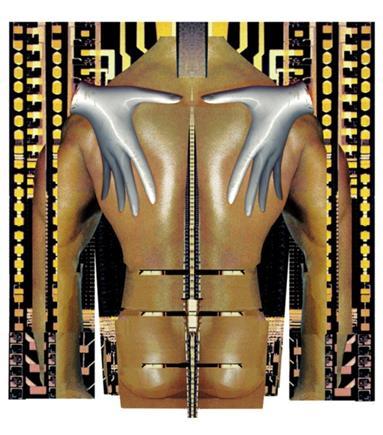

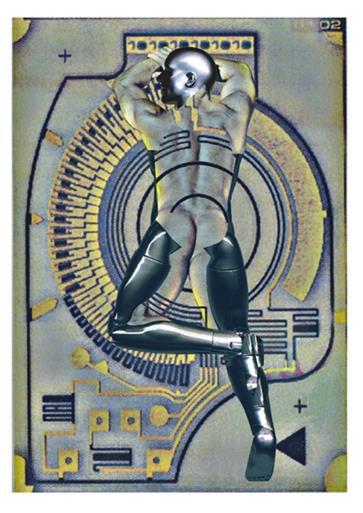

A few artists utilize humor to create dissembling odes to the phallus. Aisjah Hopkins’s penises in Contentment (1987) and Agreement (1987) appear as luscious rosy fruit sprouting in thickets. The penis is gift wrapped in Nicole Craine’s Bow (2010) and bejeweled in Arabella Decker’s playfully ironic Family Jewels (2005). Corinne Whitaker transforms it into a shiny metallic ornament in Ornamental Man (2010), and Trudi Charnoff Hauptman puts it away in a special storage box for safekeeping in Open Only on Special Occasions (2010).

Other artists deploy approaches that range from

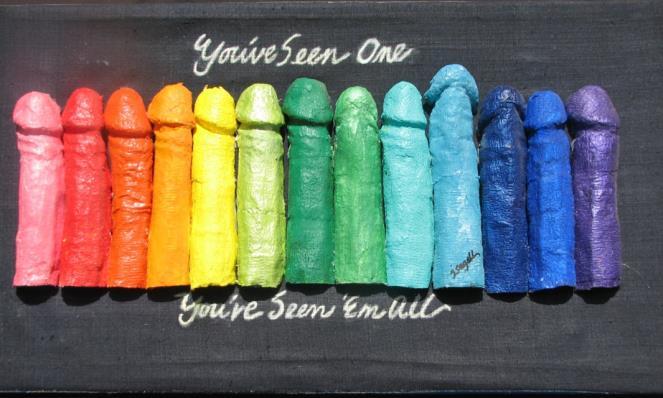

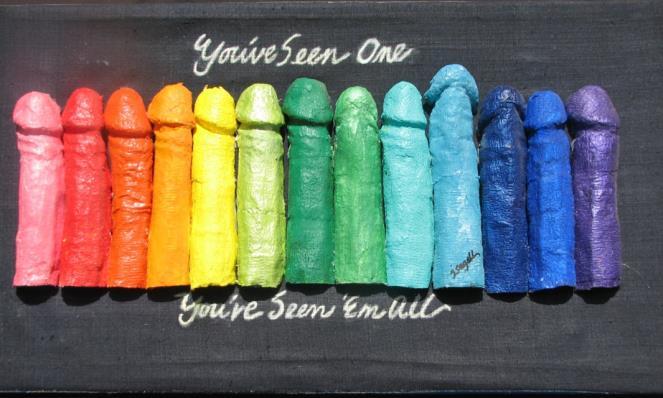

subtle critique to biting satire. The legacy of the white penis as phallus is noted without any obvious fanfare with Ruth Water’s alabaster marble sculpture Penis (1995). But perhaps Water’s understatement is precisely the point. Judith Segall tells it like she sees it with You’ve Seen One, You’ve Seen ‘Em All (1994). Segall goes one step further in Penises and Tallises (Thou Shalt Put No Gods Before Me) 1996, juxtaposing the penis-as-phallus with the symbolic law of the Father (Jewish law). In so doing she locates the source of male phallic power and superiority within the sanctions of religion. As phallus, a handsaw becomes a menacing tool for domination in Jacki Orr’s Veni Vidi Vici (2009).

Alternatively, Elizabeth Stephens addresses penis size mythologies from a lesbian-turned-ecosexual perspective with her bronze sculpture, Ron Jeremy’s BVDs (2008). Porn star Ron Jeremy is legendary for the size of his cock; however, Stephens regards the penis as just “one erotic object in a field of visual objects.” In an email Stephens writes: “I find more erotic, for instance female genitalia, trees, dirt, water, mountains and in terms of this competition it doesn't really stand up as the most powerful object of desire.”22 Stephens gazes beyond Jeremy’s famous anatomy to focus on the abject qualities of his dirty underwear. Unimpressed by either the length or girth of a penis, Stephens provides a humorous reality check to those willing to ignore a man’s unsightly appearance and lack of personal hygiene just because he has a big you-know-what.

Juana Alicia provides intriguing counterpoints with her intimate painting, Corazón de Melon.

Juana Alicia focuses the viewer’s attention on male body parts that can provide much female sensation and pleasure: the mouth, the lips, and the tongue. In so doing, Juana Alicia reminds heterosexual women

23

to look beyond the penis as a source for female sexual pleasure.

Intertextualities and Appropriations

In the 1960s Julie Kristeva invented the term “intertexuality,” which refers to the relationalities between texts.23 Given the premises of Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze it is not surprising to note the prevalence of women artists recalling, referencing, and commenting upon previous art works, literary texts, and even critical theories that have shaped masculinist art visual culture and the ways we think about visual culture and art. The most prominent example of intertextuality in the exhibition was also its source of inspiration: ORLAN’s Origin of War (1989) (Fig. 4), which is a flagrantly feminist response to Courbet’s notorious Origin of

the World (1866) (Fig. 3).

ORLAN replaces the woman’s vulva in Courbet’s painting with an erect penis in her photograph. ORLAN not only diminishes the power of the phallus by ascribing to it only a mediocre size;24 she boldly asserts that it is responsible for society’s ultimate act of violence with her choice of title, and she commemorates that viewpoint by including the gilded frame as part of her piece.

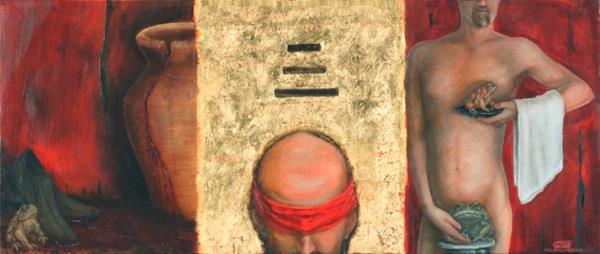

Photographer Della Calfee repurposes men’s bodies while recalling ancient Greek Erechtheum temples with stone pillars carved in the shape of Caryaid maidens in her photograph, Men as Table (1991).

Xian Mei Qiu gives art history a queer twist with In the Manner of Gabrielle d’Estrees (2011). The

24

(left, figure 3) Gustave Courbet. (1819-1877). The Origin of the World. 1866. Oil on canvas. 18 x 22 inches. 46 x 55 cm. Courtesy of Reunion des Musees Nationaux/Art Resource, NY, Musee d'Orsay, Paris, France.

(right, figure 4) ORLAN. The Origin of War. 1989. Aluminum-backed Cibachrome. 34 x 40 inches. 102.5 x 87 cm.

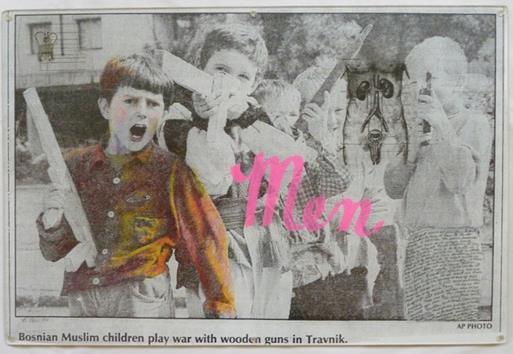

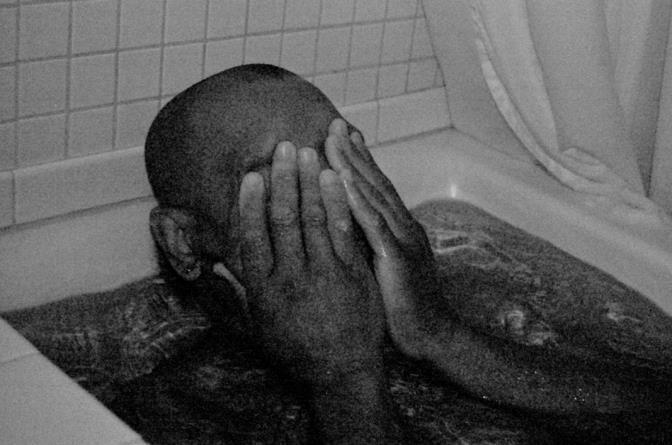

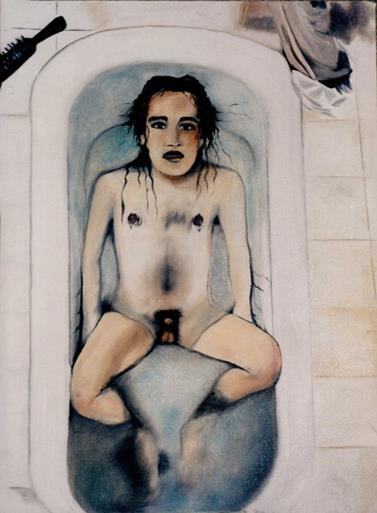

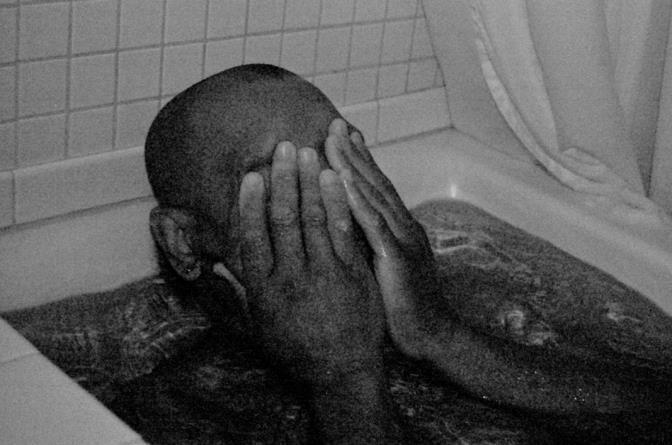

viewer is left to wonder what are the resonances between the original painting of King Henry IV of France’s mistress and her sister and the two male soldiers of color in Qiu’s photograph. Olga Alexander cleverly turns the table on de Kooning’s Woman paintings with her own painting, Man (2011). The tradition of Venus at the bath is given a contemporary role reversal with Lynn Friedman’s photograph Bedtime (2010); Nancy Netherland’s Bath (2011); Karen Henninger’s Man in Tub (1999); Nora Raggio’s Andres Vulnerable to the Camera (2011), and Andres Before His PHD Dissertation Soaking in the Bathtub (2011). Raphael’s The Three Graces (1504-1505) is the source of inspiration for the male figures of Yuriko Takata’s The Three Graces Paperboy Dolls (2011).

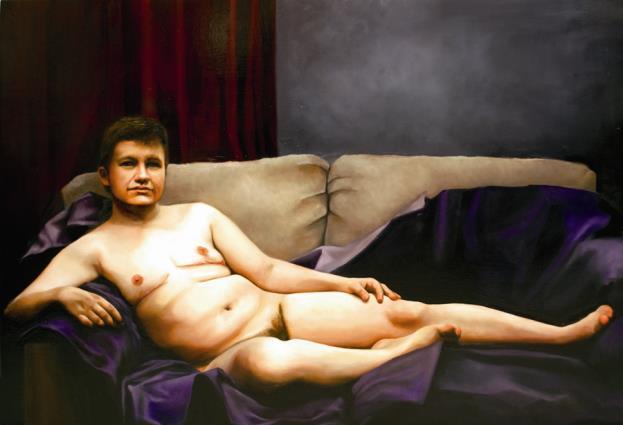

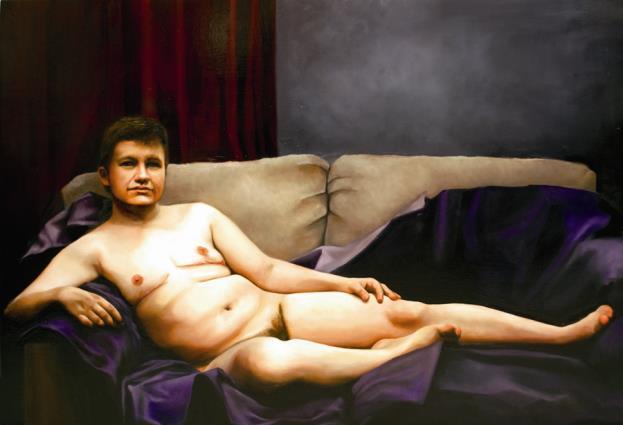

Michal Gavish’s watercolor, Life Drawing on a Couch: Homage to Zigmund and Lucian (2011) takes on the dual legacies of Sigmund Freud: his theories and his grandson, the late painter Lucian Freud. Gavish replaces “Big Sue,” the model of Lucian Freud’s famous painting Benefits Supervisor Sleeping (1995), with an equally rotund older man. Given that Freud’s painting broke the world record in 2008 for the highest price for a painting by a living artist ($33.6 million), Gavish’s choice of tribute also speaks to women artists’ ongoing struggle for equal compensation. On a more positive note, Tracy Brown illustrates how earlier feminist art history can inspire younger feminist artists with her witty remediation of Nochlin’s aforementioned notorious photograph, B-A-N-A-N-A-S (2011).

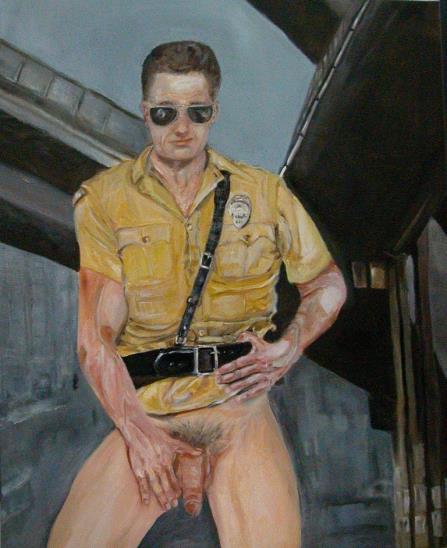

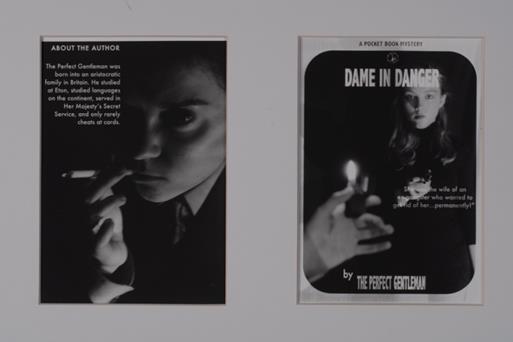

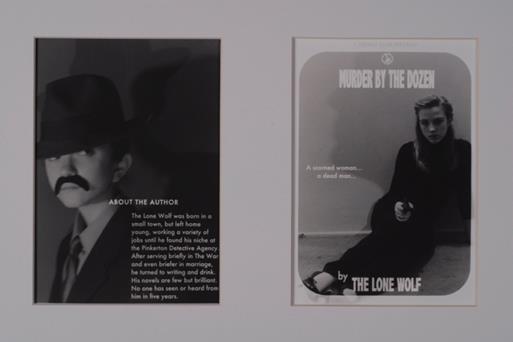

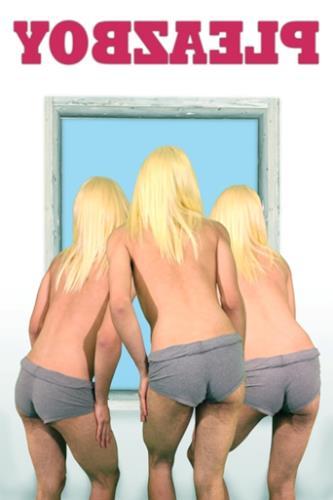

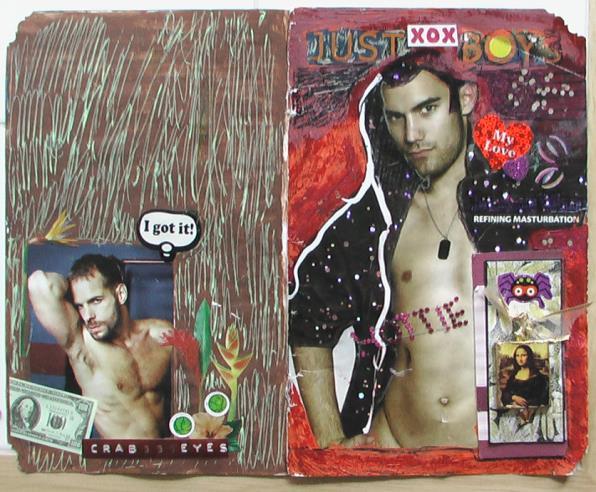

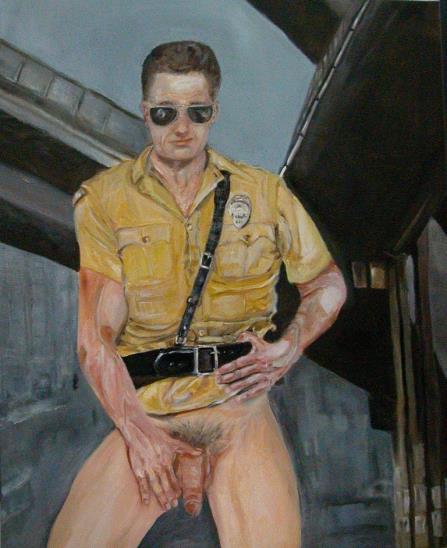

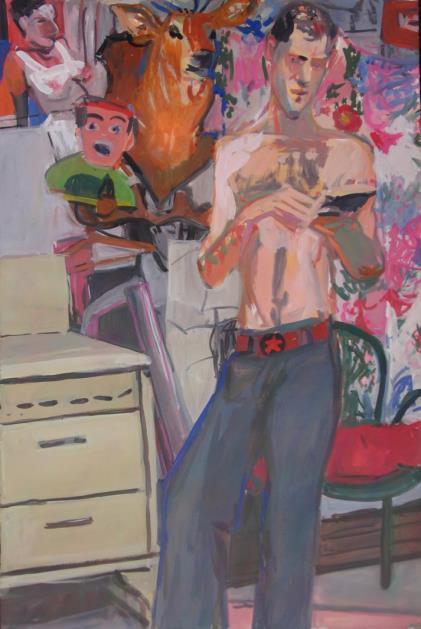

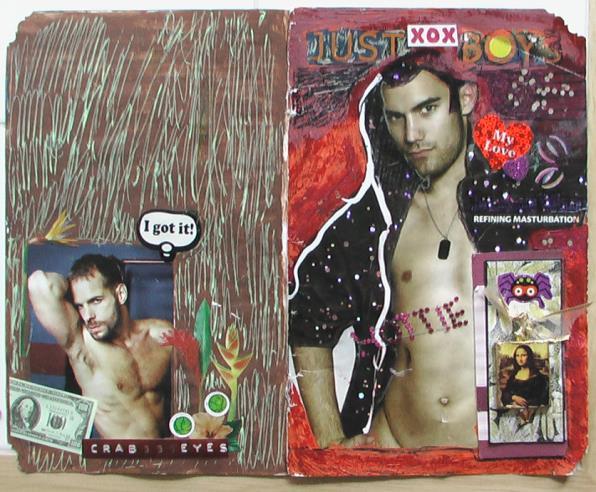

The intertextual references extend to other types of texts as well. Kelsi Mannhalter parodies Playboy magazine with Pleazboy (2011) and advertisement for women with Smooth (2011). Jenny Wrenn references gay male porn imagery with her painting

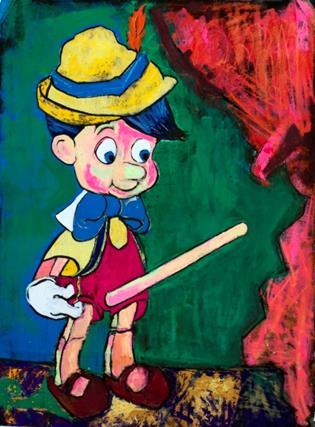

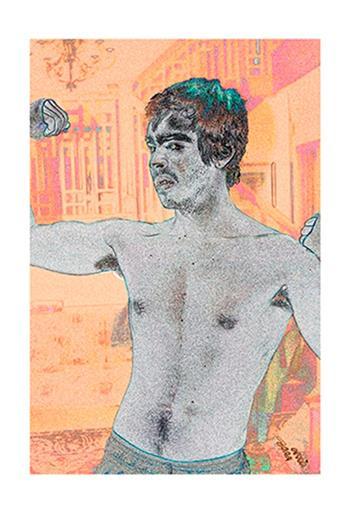

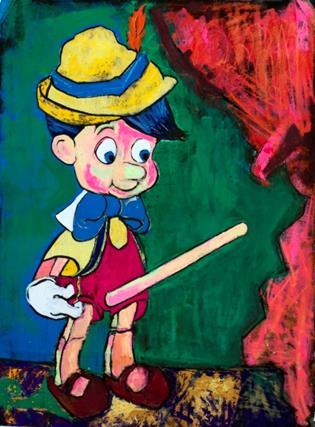

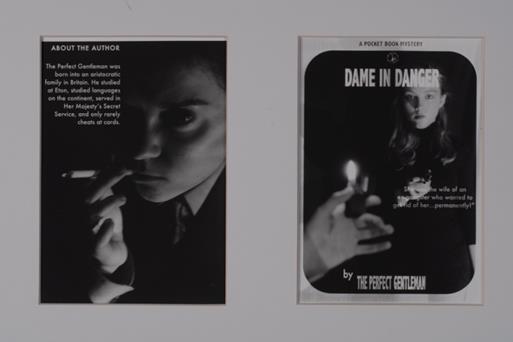

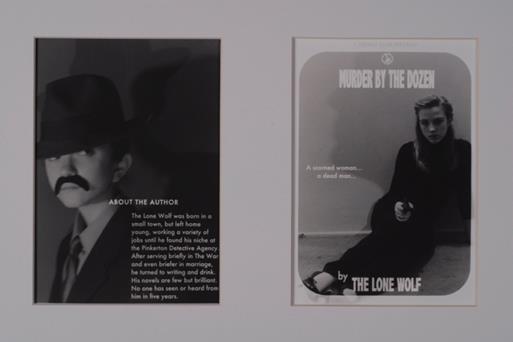

The Traffic Stop (2007). Cat Lynch revamps pulp detective novels with gender performativity in The Perfect Gentleman, from the Pulp Series (2010) and The Lone Wolf (2010), while Jeanette May incorporates quotations from female writers within the frames of her performative photographs Easy on the Eyes: Lelia (2010) and Easy on the Eyes: Dorothy (2010). We see a contemporary retelling of an ancient myth of role reversal without any sugarcoating in Erika Meriaux’s painting Heracles and Omphale (2010). Sheila Finnigan appropriates both Gertrude Stein’s highbrow modernist poetry and Walt Disney’s pop culture Pinochio in her postmodernist satire, A nose is a nose is a nose (2011).

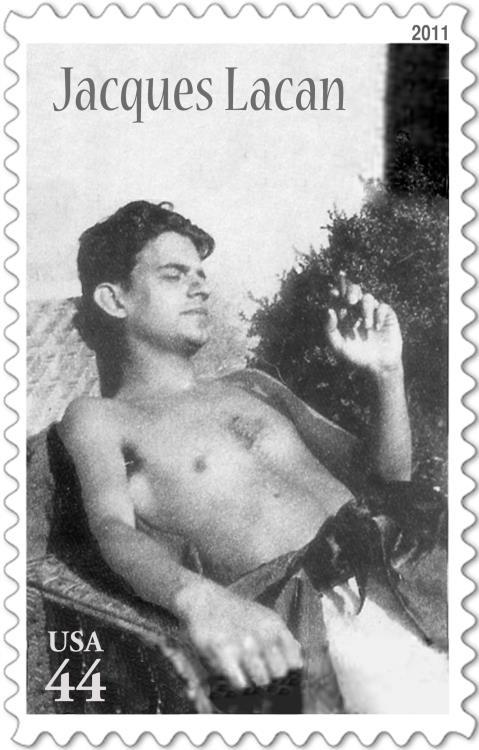

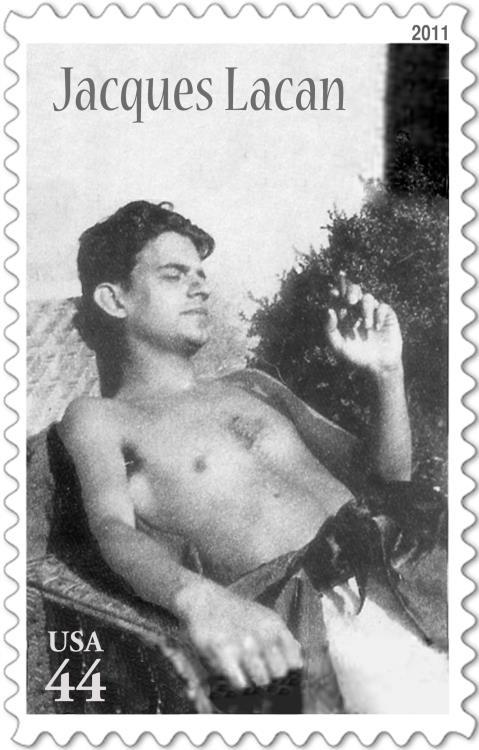

Jill O’Bryan responds to all the feminist theory written in response to the theories of psychoanalyst Jacque Lacan, particularly his ideas on the phallus as the signifier of the law of the father. More specifically, O’Bryan addresses the fetishization of Lacianian theory by creating headfuck/bodystamp (2011), a mock page of U.S. postal stamps. Lacan is shown to have been quite the male pin-up while holding a Freudian cigar. By objectifying Lacan, O’Bryan directly challenges feminist investments in his theories.

MasculinitiesandGenderPerformativity

So much was written (mostly by heterosexual men) on the analysis of men and masculinity when the interdisciplinary field of masculinity studies emerged during the 1990s that at least one scholar deemed it by 2000 as “academic Viagra.”25 Among the more influential studies written during this period was Masculinities (1995) by Australian sociologist R. W. Connell, who posits that masculinity is a relational term, one that only has meaning in relation to the concept of femininity.26 We see

25

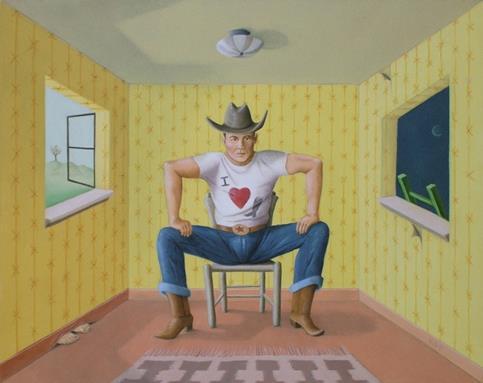

Connell’s view affirmed in the depiction of men as lovers, husbands, friends, fathers, brothers, and even prospective suitors. Does Diana Krevsky’s satiric caricature, Beware of the Troll Man (1993), for instance, reflect more men on a date or heterosexual women’s oft-quixotic struggles to meet Mr. Right? Connell furthermore examines the social construction of what he calls “hegemonic masculinity”:

Hegemonic masculinity can be defined as the configuration of gender practice which embodies the currently accepted answer to the problem of the legitimacy of patriarchy, which guarantees (or is taken to guarantee) the dominant position of men and the subordination of women. 27

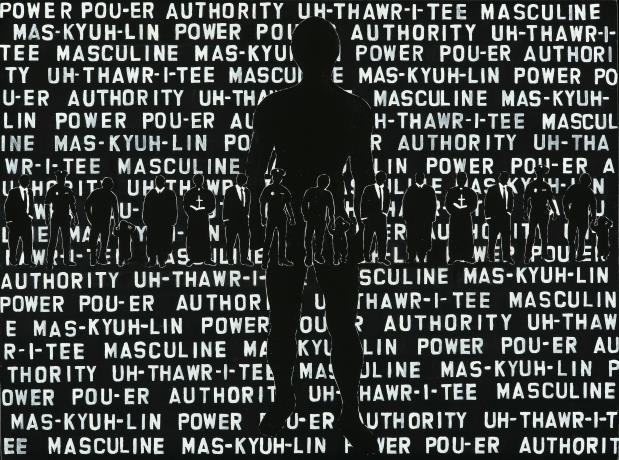

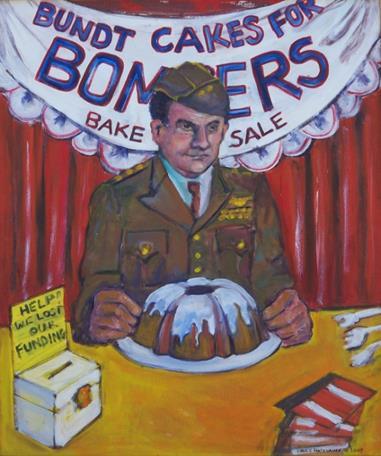

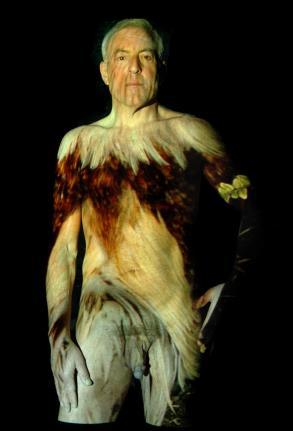

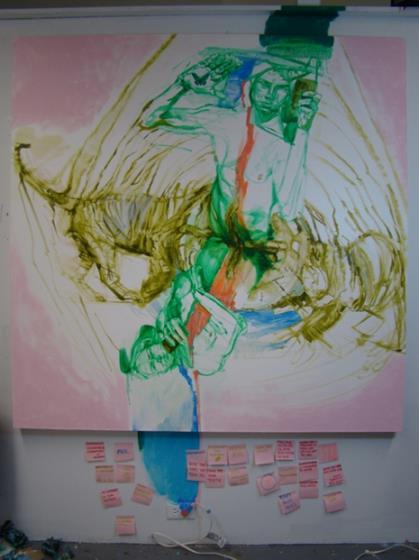

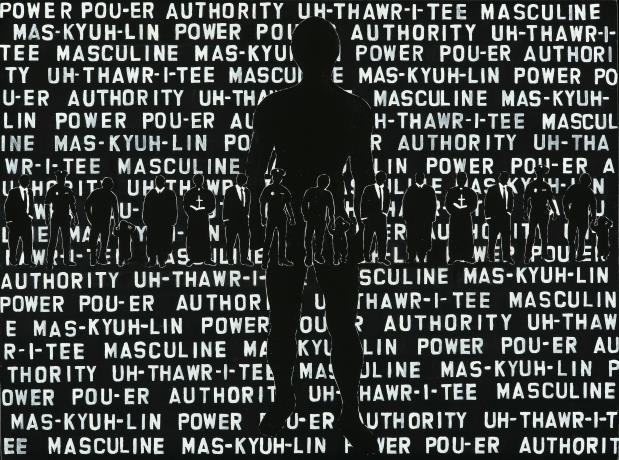

What constitutes hegemonic masculinity is neither static nor fixed. Connell suggests that it is much more precarious and transitory than what is commonly believed. With her conceptual painting Power Authority Masculine (2011), Karen Gutfreund reviews some of the ways hegemonic masculinity is currently articulated through social roles, clothing, and language in American society.

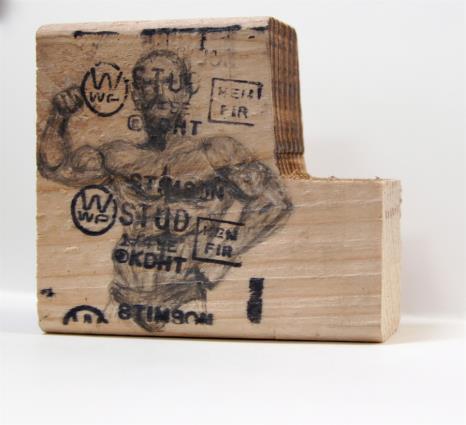

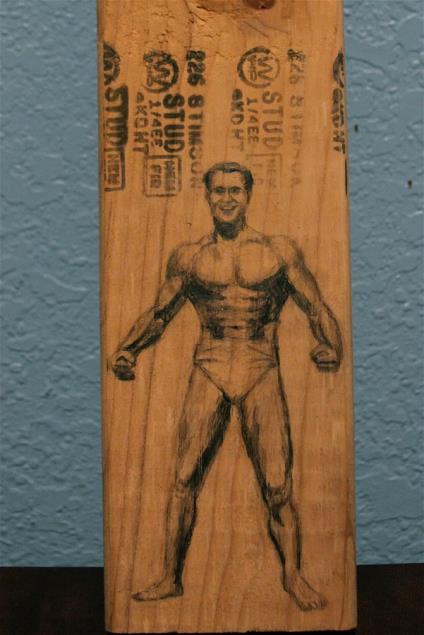

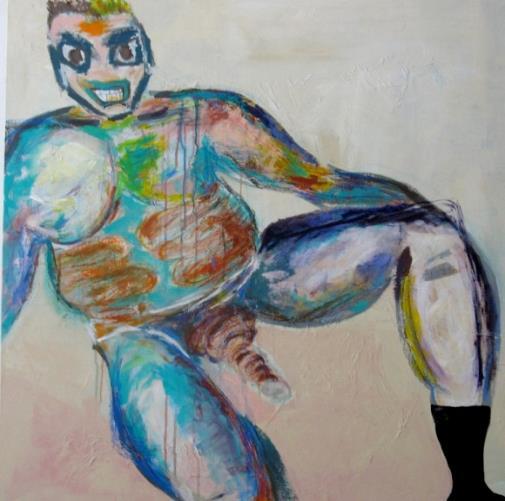

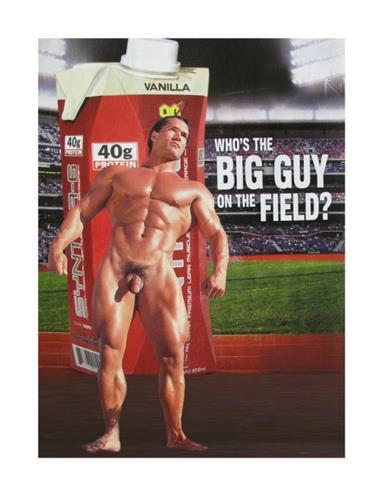

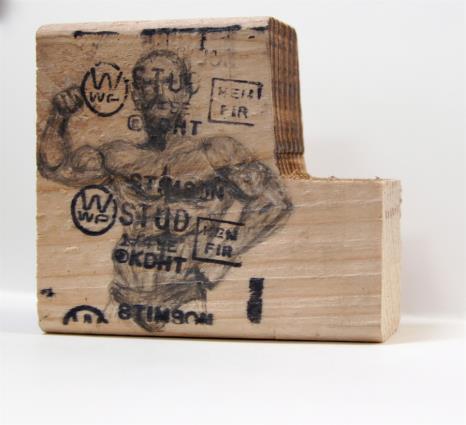

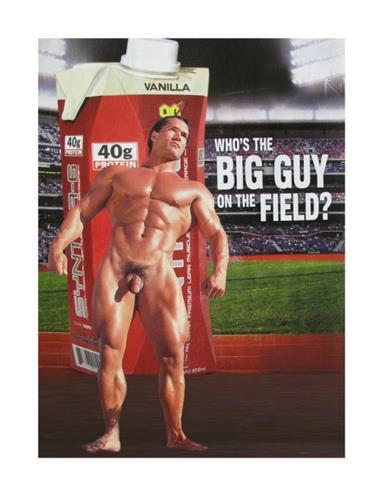

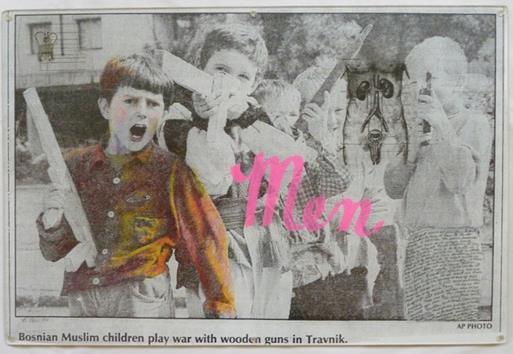

Since hegemonic masculinity is exalted above the rest, Connell makes the case that there is not one masculinity, but multiple masculinities existing simultaneously in any culture. In effect, Connell argues that to understand multiple masculinities, we have to examine how they are socially organized, produced, practiced, and reproduced, which is why this exhibition is not just about looking at men and masculinity, but about examining society. What are women artists’ views about the links between men and sports, for example? Jan Wurm seems to affirm

sociological views regarding male socialization and competitiveness with Golfers (2009). Adoration in the Steroid Era (2010), Priscilla Otani’s playful conceptual work comprised of a baseball bat and two balls, raises questions about American culture’s worship of players such as Jose Canseco whose physical prowess has recently been revealed to be attributed to steroid usage. Another humorous conceptual work, Brenda Oelbaum’s Does This Make My Dick Look Big?

Carpe Carp II (2011), links amateur fishermen’s perchant to display proudly their catches to the male obsession with penis size.

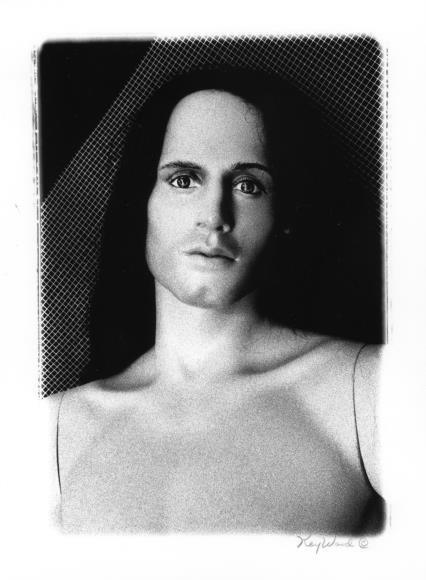

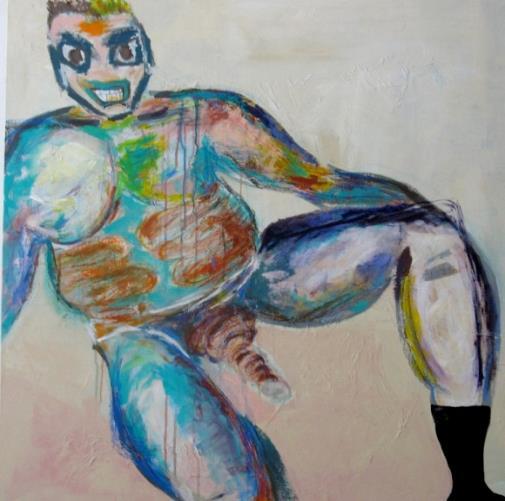

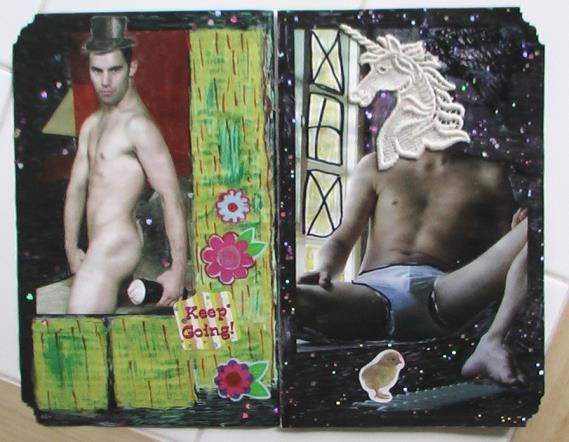

A number of works in Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze seem to have been inspired by Judith Butler’s evolving theories of gender performativity, which since the publication of her seminal Gender Trouble in 1990 have greatly contributed to new understandings of gender. Gender for Butler is a repetitive act, a performance, a “kind of persistent improvisation that passes for the real.”28 As perhaps the most visible type of gender performance due to its either parodic or hyperbolic repetitions, gestures, and corporal stylings, drag points to “a certain ambivalence”29 about having one’s masculinity being viewed by hegemonic heterosexuality—to use Butler’s term—as subordinate or marginalized. The drag queens in Linda Friedman Schmidt’s When Everyday Is Halloween (2008), Karen Mathew’s Lips (2008), and Emily Yost’s Untitled (‘Faux Queen’) (2011) are shown to convey that ambivalence with intention and dignity.

Drawing from Butler cultural theorist Judith Halberstam claims in her monumental 1998 study, Female Masculinity, “it is crucial to recognize that masculinity does not belong solely to men, has not been produced only by men, and does not properly express male heterosexuality.”30 Artist Nancy

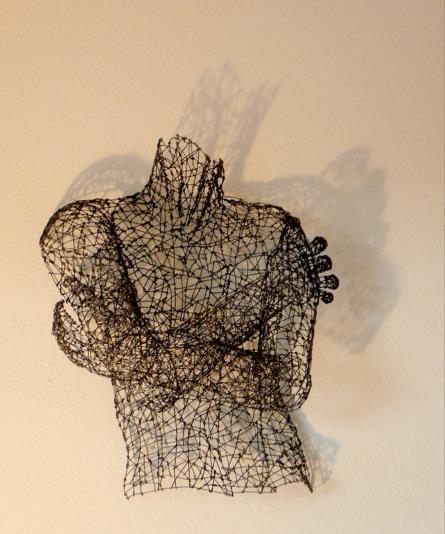

26

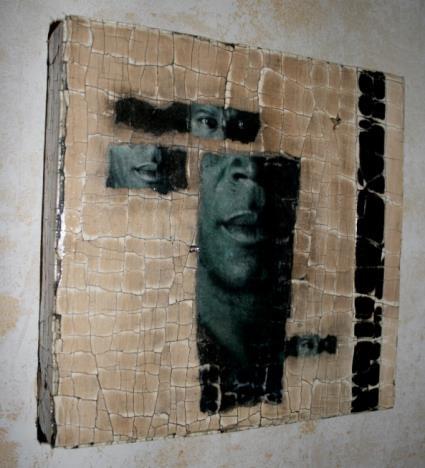

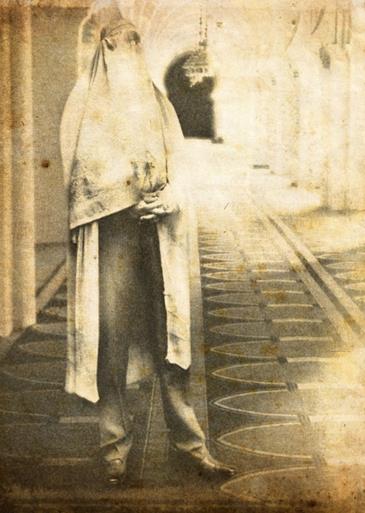

Grossman anticipated Halberstam’s ideas with her art, particularly, her carved life-sized head sculptures wrapped in black leather dating back from the 1960s to 1980s (See Fig. 5). By referring to these iconic heads as self-portraits, Grossman suggests that masculine qualities conventionally attributed to men—such as aggression, strength, cruelty, and sadism—can be expressed by everyone.

Halberstam devotes a chapter on lesbian drag king performance to make her case. Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze includes performative photographs and video performances of female

masculinity and drag kings because women artists’ embodied knowledge of masculinities can be rendered visible through performance, gesture, and corporal styling. Such knowledge is often the result of looking closely at men and their behaviors, which is why performance, perhaps more than any other art medium, can be used as a feminist strategy to expose men’s rituals of domination, whether it be through imitation, parody, or stylized hyperbole. For example, queer performance artist Tania Hammidi celebrates her self-fashioned female masculinity in her glamorous photographic self-portrait, Look (2011).

27

Figure 5. Nancy Grossman (b.1940).

Haifisch. 1970. Leather, wood, porcelain and hardware. 16 x 8 x 10 inches, signed and dated. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY.

Annie Sprinkle’s performative photographs that make up The Seven Men Inside Katherine Gates (1990), which she did in collaboration with artist Katherine Gates, are early yet sophisticated examples of drag king performances—particularly the photographic performance of Gates as a drag king performing as the male drag queen “Bubbles” Galore parodying a heterosexual woman. Does it matter much that Sprinkle’s collaborator is a heterosexual woman? It shouldn’t, because according to Halberstam, neither female masculinity nor drag king performance is exclusively lesbian.31 A more recent example of drag king photographic performance is Hammidi’s reflective self-portrait Mirrors of He (2008), which suggests that there is no original nor prototypical image of masculinity. During her remarkable video Playing Peter (2007), Erika Swinson documents the process of how quickly and easily the female body can be modified to appear masculine. All a girl needs is some duct tape eye pencil, socks, boxers, and a good suit. Swinson then performs male rituals such as shaving, reading a newspaper, and smoking a cigar.

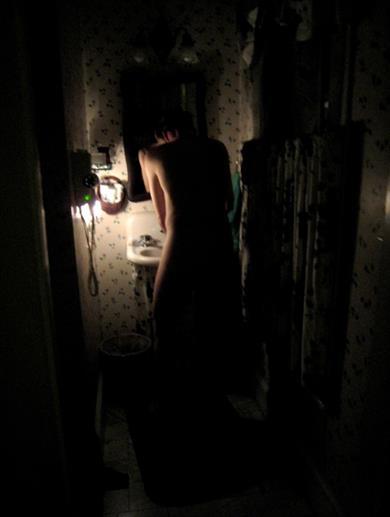

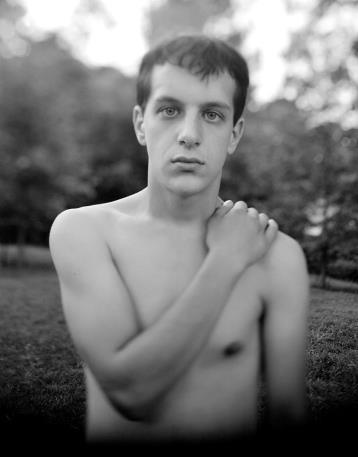

Along with Butler and Halberstam’s respective groundbreaking scholarship, these works by Sprinkle, Hammidi, and Swinson raise some important questions for the exhibition: Who gets to be recognized and acknowledged as a man? Or a woman artist? What about those who are queer and transgender, as in the case of Molly Marie Nuzzo’s Noah (2011), or those who confound gender categories and sexual identities, as in the case of Tristan Crane’s “genderfucking”32 photographic subjects, the underground porn stars James Darling, Quinn Valentine, and Dex Hardlove? By destabilizing gender and sexual identities Nuzzo’s and Crane’s subjects envision new possibilities.

Eroticism, Pornography, and the Impact of New Media Technologies

And what do the works in Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze reveal about contemporary sexuality and eroticism? Already in 1993 Linda Williams observed that “distinctions between the erotic and the pornographic are often elusive, sometimes irrelevant and always political.”33 Yet Williams was able to assert a basic distinction:

Pornography aims frankly at arousal; it addresses the bodies to its observers in their sexual desires and pleasures. It boldly sells this sexual address to viewers as a commodity and it does not let aesthetic concerns or cultural prohibitions limit what it shows. Erotic art, on the other hand, is traditionally much less bold and (somewhat) less commercial. Because it is committed to the ideals of an art which is supposed to beyond commodification and to reside within the rational limits of good taste, it does not directly (although it may indirectly) `sell’ its sexual address.34

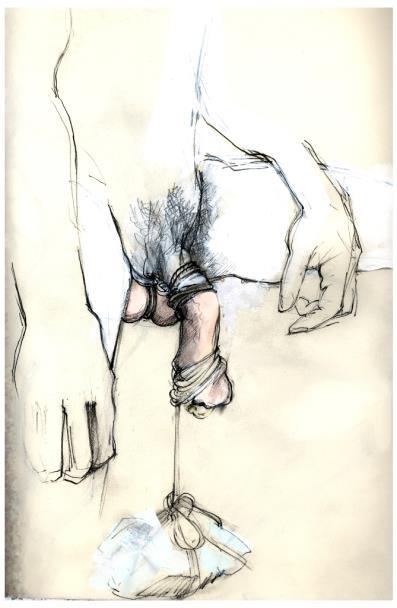

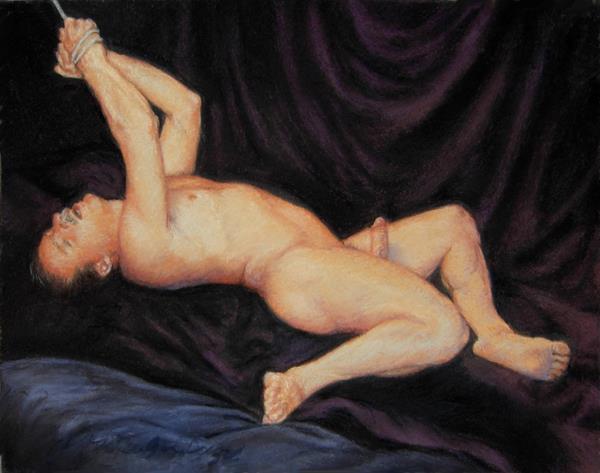

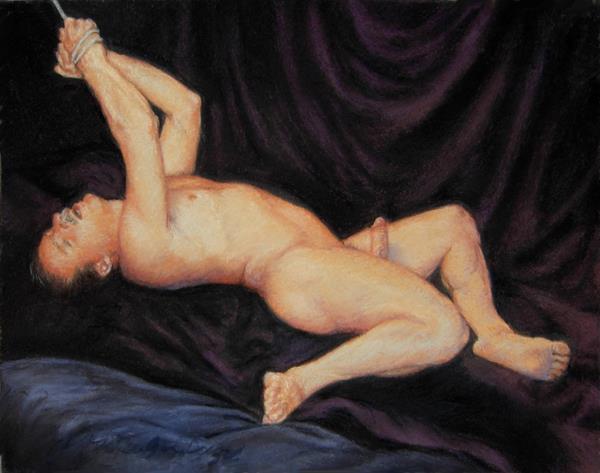

Since then, the distinctions have become arguably even murkier as the impact of digital and new media technologies on contemporary sexuality, eroticism, and pornography is undeniable. For example, we see no shortage of male exhibitionism within the exhibition, as there are multiple images of men’s crotches with legs spread apart: Ellen Kieffer’s Subjective Perspective (2010), Zina Al-Shukri’s Look Into My Eyes (2010), Sara Hopkin’s Spread Your Legs (2011), and Elizabeth Sowell-Zak’s Personality: Angel Seated (2010). Somewhat related to exhibitionism are S&M role playing and displays of bondage, and we see several bounded submissive men with

28

Merrilyn Duzy’s Bound (2009), Carolyn Weltman’s Gods and Men (2008), and Nancy Peach’s Male Bondage (2011).

Images of male autoeroticism abound in the exhibition, perhaps as the ultimate form of contemporary American individualism what Robert Putnam categorized as “Bowling Alone.”35 These masters of their own domain (to borrow a euphemism from a famous Seinfeld episode, “The Contest”) appear completely self-involved in their pleasure, unaware of their surroundings or of others. They appear in Merrilyn Duzy’s painting Repose (2009); Sharon Leong’s paintings Handgela (2002); Jan Wurm’s painting Reverie (2008/9); Tristan Crane’s photograph Cassidy (2011), Shilo McCabe’s photographs Jim (2011), Ned (2011), and Damani (2011); and Amy-Eyse Neer’s The Affair (2009). In all of these works, the viewers are positioned as voyeurs, not invited participants.

I expected to see many images of penises and phalluses, aware of the tradition of “prick artists.”36 I must admit I did not anticipate the number of images of onanism submitted. What threw me entirely for a loop was to see how within these images men seem blissfully unaware of the viewer or their surroundings. I wondered: must images of men masturbating position the viewer as an intruding voyeur? Do these images reflect a society that is increasingly isolated and alienated from others, including one’s sexual partners? Or are they suggesting that one doesn’t need a sexual partner to reach fulfillment, validating masturbation as an important part of sexuality?

In contrast to Annie Sprinkle’s Teeny Tiny Big Black Dick, these more recent works for the most part do not suggest sexual connection. M. Ode to Fritz Lang

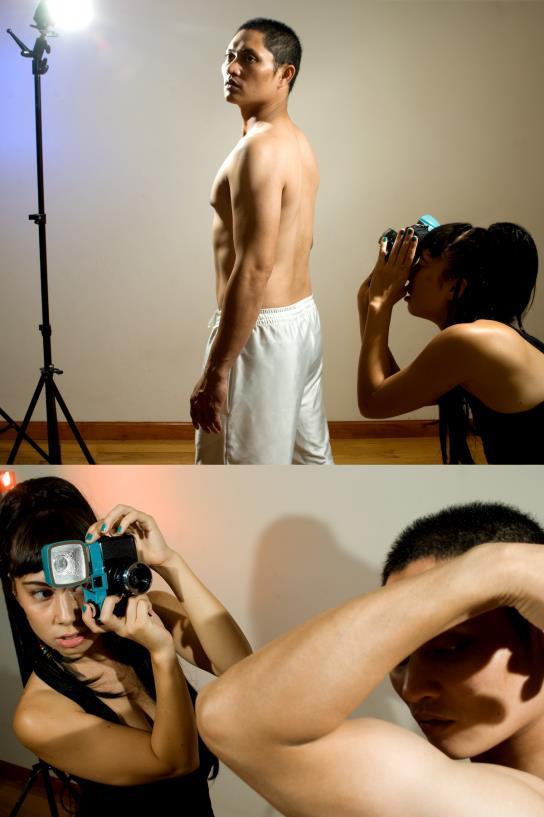

Redux (2011), Melissa P. Wolf’s digital sequential still photographs of a flat screen monitor playing The Chelsea Tapes (1983-1995), the video she made with her then partner (now husband and art collaborator) Paul Lamarre, documents male masturbation as part of an artistic collaboration as well as sexual connection. During The Chelsea Tapes, Lamarre performs for the viewer and Wolf, who is behind the video camera, as he jerks off and eventually ejaculates. With her still photographs of “the money shot,” Wolf both challenges her audience and makes several critical points. The first main point calls attention to cultural prohibitions regarding the visual representation of the money shot. As Linda Williams has pointed out, the money shot is part of what women frequently see when viewing the male body in pornographic video and film even though it functions in pornography primarily as a fetish for men. 37 Its representation does not seem to exist outside of the pornographic realm even though women can (but not always) view men ejaculating during heterosexual sex. Wolf’s photographic triptych is an exploration of how men’s ejaculating bodies may be artistically represented. Second, M. Ode to Fritz Lang Redux is a testament of how mediated eroticism and sexuality have become—a point that Shilo McCabe also makes vividly with her photograph Damani. Finally, third, Wolf’s images are a reflection of the extent to which the distinctions between erotic and the pornographic have become blurred.

The Weiner Effect

By happenstance this exhibition can be considered extremely timely. During the period I was jurying this exhibition in May-June 2011, Arnold Schwarzenegger was exposed for having had an extramarital affair

29

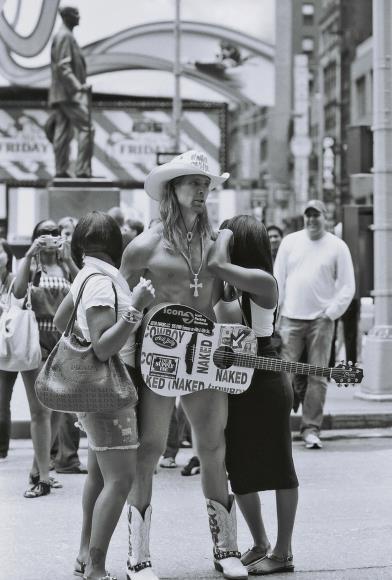

with his housekeeper, fathering a child with her. Congressman Anthony Weiner of New York tweeted a crotch shot, apparently by mistake, which ultimately resulted in even more intimate and explicit photos being released that led to his reluctant and teary-eyed resignation. These examples and others (think John Edwards and New York State politician John Lee) beg the question: why can’t these guys in power keep their pants zipped? In the case of Arnold Schwarzenegger, perhaps the biggest shocker was that this news did not become public earlier. The Guerilla Girls on Tour’s poster My Fellow Californians (2007) did attempt to warn the electorate about the former California governor’s past record as a groper and sexual harasser to no avail. With the case of Anthony Weiner, the American public witnessed a white male politician’s desperate call for attention, to be looked at and admired (in the case of his tweeted bulging underpants shot, for example, the photo was sent “as a joke,” unsolicited).

Perhaps men like these can learn from our exhibition, to see how women view them. . . or choose not to. Is it at all astonishing that no image of an actual white male politician in a suit was submitted to the exhibition? Such omissions seem to confirm Halberstam’s claim that “masculinity. . . becomes legible as masculinity where and when it leaves the white male middle class body.”38 Nevertheless, I can’t help but think that the lack of such images also suggests that women artists may share Halberstam’s “degree of indifference to the whiteness of the male and the masculinity of the white male and the project of naming his power.”39 Are women artists deliberately ignoring socially, politically, and financially powerful men with their displays of dominant and hegemonic masculinity?

Are women artists intentionally choosing not to represent them as artistic expressions of feminist resistance, critique and empowerment? Could it be that women artists simply do not find the actual bodies of white men who wear suits all that compelling aesthetically, let alone erotically appealing? The exhibition Man as Object: Reversing the Gaze leaves it up to its viewers to draw their own conclusions.

30

NOTES

1 John Berger, Ways of Seeing (London: British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin, 1972), 47.

2 Linda Nochlin, “Starting from Scratch: The Beginning of Feminist Art History,” in The Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s, History and Impact, eds. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994), 135-136. Buy My Apples and Nochlin’s photograph Buy My Bananas (1972) are reproduced on page 136.

3 For a full account and analysis along with reproductions of the nineteenth-century photograph and Nochlin’s Buy My Bananas (1972) see Richard Meyer, “Hard Targets: Male Bodies, Feminist Art, and the Force of Censorship in the 1970s” in WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution, ed. Lisa Gabrielle Mark (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 2007), 364-371.

4 Cagle, Jess. “Reynolds Unwrapped.” EW.Com 27, March 1992 http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,309960,00.html

5 Susan Bordo, The Male Body: A New Look at Men in Public and Private (New York: Farrah, Straus and Giroux, 1999), 18.

6 Eleanor Dickinson, “Interview with H. W. Janson, February 1, 1979,” College Art Association , Women Artist News, September/October 1979, 12. Qtd. in Eleanor Dickinson, “Report on the History of the Women’s Caucus for Art” in Blaze: Discourse on Art, Women and Feminism, eds. Karen Frostig and Kathy A. Halamka (Newcatstle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2007), 38.

7 Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Women, Art, Power (Harper & Row, 1988), 145-178.

8 Loretta Lynn’s song “We’ve Come a Long Way, Baby” was one of the top country songs of 1978. See the website Playlist Research: A Resource for Music Researchers. http://www.playlistresearch.com/1970s/1978countryhits.htm. The lyrics are easily accessible online, and one can view several versions of Loretta Lynn singing the song on YouTube.

9 For more detailed discussion of the “abstract figurative” style of Schneeman’s early paintings, see Kristine Stiles, “The Painter as an Instrument of Real Time,” in Carolee Schneeman, Imaging Her Erotics: Essays, Interviews, Projects. Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 2002, 3-16.

10 William S. Wilson, email correspondence to the author, August 13, 2011.

11 Sarah Kent and Jacqueline Morreau, “Lighting a Candle,” in Women’s Images of Men, eds. Sarah Kent and Jacqueline Morreau (London: Pandora, 1990), 20.

12 Sarah Kent and Jacqueline Morreau, “Preface” in Women’s Images of Men, eds. Sarah Kent and Jacqueline Morreau (London: Writers & Readers Publishing, 1985), 1.

13 Naomi Salaman, “Introduction,” in What She Wants: Women Artists Look at Men, ed. Naomi Salaman, Intro. by Linda Williams (London and New York, Verso: 1994), 65.

14 For more information on the 2007 Girl on Guy exhibition see http://cms.colum.edu/girlonguy/.

15 See Jay Bolter and Richard Grusin, Remediations (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004) for more about remediations.

16 Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in Patricia Erens (ed), Issues in Feminist Film Criticism (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1990), 34. Originally published in Screen 16, no. 3 (Autumn 1975), 6-18.

17

E. Ann Kaplan, Women and Film: Both Sides of the Camera (New York and London: Routledge, 1983), 23-35.

18 Cheryl L. Nicholas, “Gaydar: Eye-Gaze as Identity Recognition Among Gay Men and Lesbians,” Sexuality & Culture 8, no. 1 (2004): 60-86.

19 Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1977).

20 Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978). See also Michel Foucault, The Birth of the Clinic: An Archeology of Medical Perception, trans. A. M. Sheridan Smith (New York: Pantheon Books, 1973).

31

21 Richard Dyer, “Don’t Look Now,” Screen, 23, nos. 3-4 (1982), 72. See also Lola Young, “Mapping Male Bodies: Thoughts on Gendered and Racialized Looking,” in What She Wants: Women Artists Look at Men, ed. Naomi Salaman, Intro. by Linda Williams (London: Verso, 1994), 41-42.

22 Elizabeth Stephens, email correspondence with the author, August 14, 2011.

23 See Julia Kristeva, Desire in Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art (New York: Columbia University Press, 1980).

24 Simon Donger, “Hybridity and Alterity in ORLAN’s Seductive Acts of Dis/Connection,” in ORLAN: A Hybrid Body of Art-Works, ed. Simon Donger with Simon Shepard and ORLAN (London and New York: Routledge, 2010), 162.