Copyright 2024 by Rosemary Meza-DesPlas. The book author retains sole copyright to their contributing images to this book. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means without prior permission in writing. www.rosemarymeza.com

ISBN: 9798325106026

Catalog design by Karen M. Gutfreund, @karengutfreundart, karengutfreund.com

2

Acknowledgments

My gratitude and love to Edward DesPlas for his steady and unwavering support.

Many thanks to the team at form & concept gallery for their collective efforts to bring this exhibition to fruition: Sandy Zane, gallery owner, Jordan Eddy, former gallery director, Christina Campbell, Brad Hart, Tiana Japp, Spencer Linford. Thank you to Karen Gutfreund for designing the catalog and for facilitating its production. I appreciate the photographers who have worked with me to document my artwork: Harrison Evans, Mariah Richstone, Marylene Mey, and Byron Flesher. Deep thanks to Karen Mary Davalos for her generous words. Gracias to Diana Solis for her generous time to shoot a portrait of me. I would like to acknowledge the US Latinx Art Forum, Mellon Foundation, Ford Foundation for their recognition and support. Finally, I would like to recognize the many family, friends, and colleagues whose assistance, encouragement and friendship has been invaluable throughout the years.

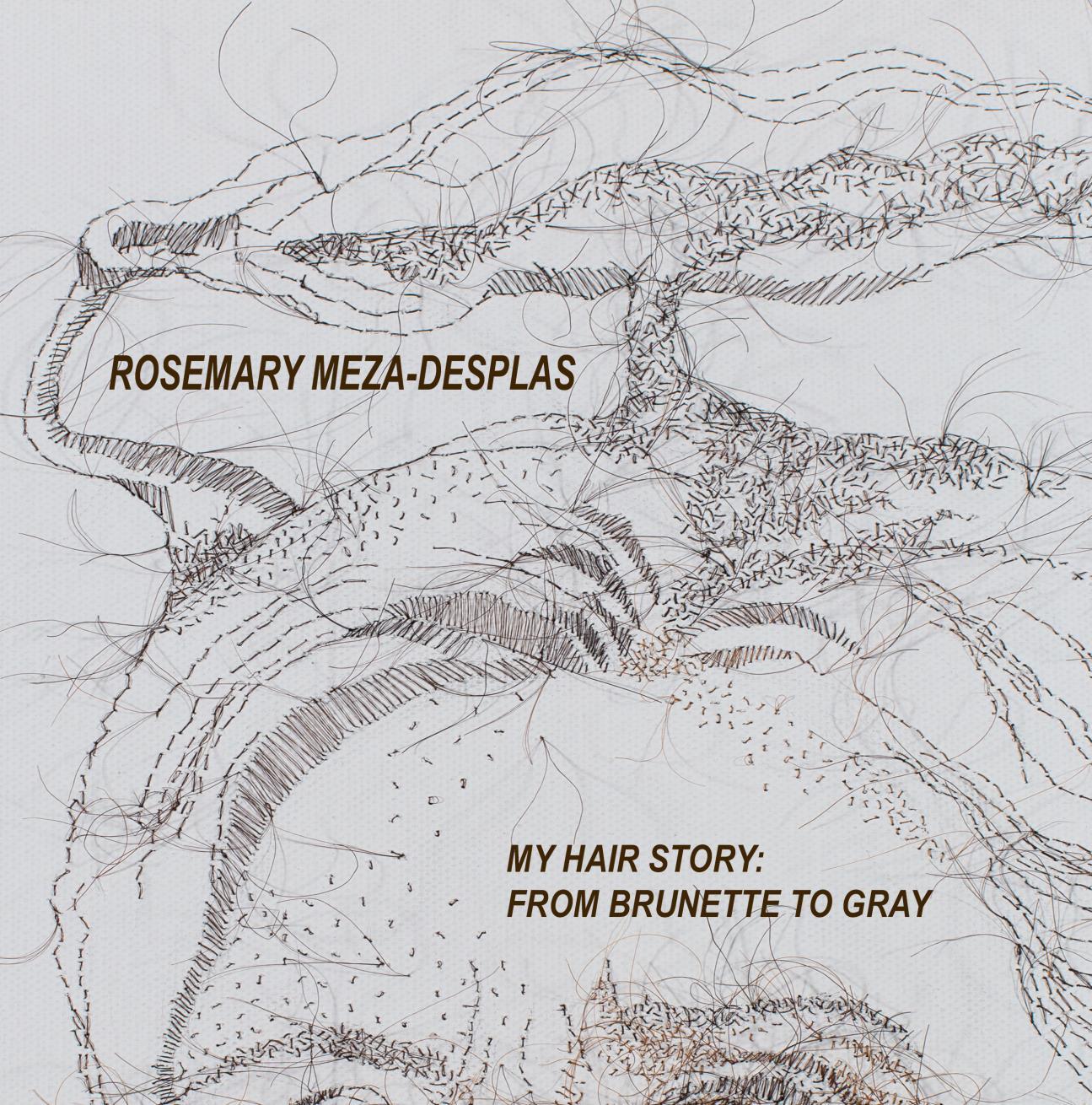

Rosemary Meza-DesPlas

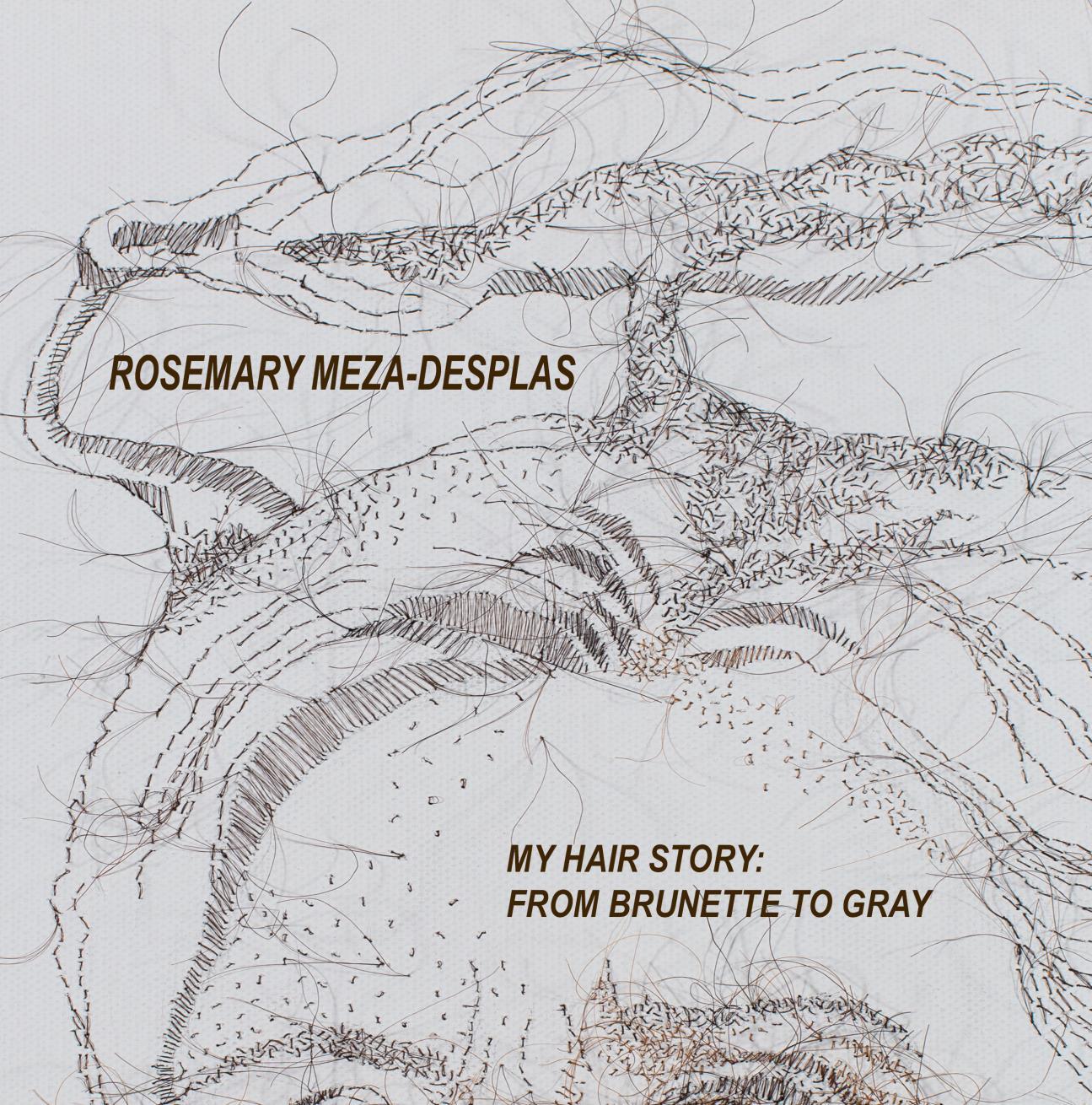

My Hair Story: from Brunette to Gray form & concept gallery

435 S. Guadalupe St., Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501 June 28 – August 31, 2024

3

Forward

My Hair Story: from Brunette to Gray features twenty-two years of embroidered human hair artworks by Rosemary Meza-DesPlas, a Spanish and Coahuiltecan artist. The exhibition highlights Meza-DesPlas' meticulous artistic process of translating drawing techniques into sewn lines and documents the evolution and experimentation of Meza-DesPlas’ use of hair, a unique medium that has become the artist's material and visual signature. Using the human body as a visual framework, Meza-DesPlas’ veracious portrayal of the feminine body challenges conventional beauty standards and emphasizes the mutable nature of a face.

Historically rooted in the women's craft movement of the 1970s, My Hair Story: from Brunette to Gray transforms hair from an ordinary fiber into a symbolic representation of age, beauty, health, power, race, religion, sexuality, and social class. Through Meza-DesPlas's sewing dexterity, critical eye, and dedication to medium, hair and its material culture acquire a symbolic aspect that challenges viewers to look at identity and femininity from a new perspective. Historical and critical research and writing inform the artist's thematically driven art, which communicates a feminist perspective on current and long standing sociopolitical issues and cultural misconceptions.

Spencer Linford, communications director at form & concept formandconcept.center

4

Rosemary Meza-DesPlas: paradoxes of human hair and feminist figuration

Born and raised by Mexican immigrant parents in Garland, Texas, a manufacturing suburb of Dallas, Meza-DesPlas lived and worked there until 2016 when she relocated to Farmington, New Mexico. Meza-DesPlas is a figurative mixed media artist, whose work “amplifies the voices of women” and “reflects the female experience within a patriarchal society.” She has produced numerous series that include human hair, which she collects from her own scalp and sews into the surfaces of paper, canvas, and mylar. Meza-DesPlas’s art expresses nepantla aesthetics through visual composition that reveal seemingly contradictory propositions, entering a visual discourse initiated by Chicana artists, such as Yolanda M. López and Ester Hernandez, who reclaim the image of the Virgen of Guadalupe.

Queer Chicana feminist writer Gloria E. Anzaldúa expands beyond nepantla, the “Nahuatl word for an in-between state.” She focuses on contemporary negotiation, ambiguity, and cooptation in the context of structural inequity, racialization, and historical erasure. According to Anzaldúa, nepantla characterizes “that uncertain terrain one crosses when moving from one place to another, when changing from class, race, or sexual position to another,” positions that are simultaneously performed and profoundly informed by social hierarchies of power. Building on Anzaldúa’s reformulation of nepantla, religious studies scholar Lara Medina proposes that it reveals Indigenous agency and the capacity to simultaneously “hold multiple” perspectives and worldviews. As such, I propose that artists living in nepantla—“nepantleras,” in Anzaldúa’s words—adjust to multiple pressures in unanticipated ways. My intention is to explore how nepantla as an aesthetic opens to multiplicity, complexity, ambiguity, and contradiction without projecting transcendence, failure, imitation, or inauthenticity onto the artists. Therefore, nepantla promotes a more capacious understanding of Chicana/o/x art, and by extension, art in the United States.

Before I explore the paradox enlivened through Rosemary Meza-DesPlas’s art, I begin with the artist’s willful connection between her practice and the so-called domestic crafts with the term fiber arts. Meza-DesPlas “approaches the process of stitching hair from a drawing perspective,” the technique in which she was trained at the University of North Texas, using the drawing methods of “hatching, stippling, and cross-hatching” to create tonal shading, depth, and weight with threads of human hair. This framing as fiber arts is a deliberate connection to the feminist interrogation of the “hierarchies of value” in art history which depreciates domestic handiwork of women of color and Indigenous women. Her use of human hair as fiber medium is one aspect of nepantla aesthetics as it aligns Meza-DesPlas with the ongoing feminist, African American, Latinx, and Indigenous investment in textile and needlework, which is a rethinking of Eurocentric perspectives about art. As art historian Elissa Auther observes, “the emergence of the hierarchy of art and craft originates in the Renaissance when the first claims were made for painting and sculpture as ‘liberal’ rather than ‘mechanical’ arts.” Complicating this hierarchy of value is racialization, sexism, and imperialism relegating “‘mere craft’ of women’s and Native people’s artwork,” particularly textile, to the margins. Although “fiber arts gained visibility in the late 1960s,” it remains subordinated in art criticism and markets, even as recent exhibitions attempt to reverse this trend. I propose that Meza-DesPlas’s incorporation of hair and its

5

application to a surface with a needle exposes the racialized and gendered hierarchies of value in the art world, thus negotiating nepantla aesthetics through hair and figurative compositions that rethink racialization, heteropatriarchy, capitalist consumption, and increasingly, ageism.

For example, the artwork March Across Your Lawn, The Grass is on Fire, Meza-DesPlas uses human hair to depict women’s feet and legs in various tempos of marching, including moments of fatigue. As the artist explains, marching is the “simplest” form of political participation as it merely requires the locomotion of the body, and this simple action typically precedes codified equity, such as the women’s right to vote or bans against the use of nondisclosure agreements to cover up sexual harassment. However, collective action also comes with risks, which is depicted by nude female bodies, a literal manifestation of social exposure that women face when they march or strategize to overcome heteropatriarchy and misogyny. The series was inspired by the numerous collective actions of the 21st century such as the #MeToo Movement. In the series of the most mundane female body parts feet, knees, and thighs the artist composes figures without contours privileged by the heteropatriarchal and racialized beauty. These bodies are full and round, rather than svelte, and from grey hair, proposing a feminist critique of narrow notions of beauty.

The isolation of the body in negative space, a visual strategy Meza-DesPlas uses elsewhere, heightens attention to the action of women marching. The decontextualized images are suggesting the general practice of female social activism rather than a specific historical moment, even when a cluster of grass appears in Marching Across Your Lawn, The Grass is on Fire. However, the decontextualized compositions also allow the work to fluctuate between refusal and reinforcement of objectification. For instance, the composition can reinforce the act of male voyeurism which also isolates female body parts through fixation. In Groundswell # 9 the shading at the crease of the top of thigh where it joins to the hip accentuates the pubic area. Even as the artist intends to foreground feminist activism and agency, the work oscillates between critique and activating the norms of heteropatriachal looking, fetishizing, or compartmentalizing of the female body. Nepantla aesthetics moves across various worldviews and refuses binary logics by implicating and doubling such logic. With nepantla aesthetics juxtaposed meanings are anticipated, rather than disregarded or used to belittle the art.

Even the loose thread-like hairs that hang from the nude body in Groundswell # 9 and Marching Across Your Lawn, The Grass is on Fire point to paradox. The loose hairs reinforce fiber artistry, but also unfinished business as if the artist did not secure the final stitch. The dangling hairs give the impression that the work, and women’s activism, is vulnerable to destruction; if the threads were pulled, the lines would disappear, as would the images of women’s agency. At the same time, the loose hairs also suggest a release from heteropatriarchal confinement since the loose hairs show that this construction of the female body is incomplete. Even as the outlines of the body are evident, the dangling threads are literally swinging loosely from the surface, tacitly implying unfinished or suspended visual compositions. Threads are both a witness to fragility and a loosening of social confinement. Finally, if nepantla can

6

resoundingly reach closure or conclusion, this paradox underscores how nepantla aesthetics not only refuse binary logic but may call this logic into question by invoking it and playing with it.

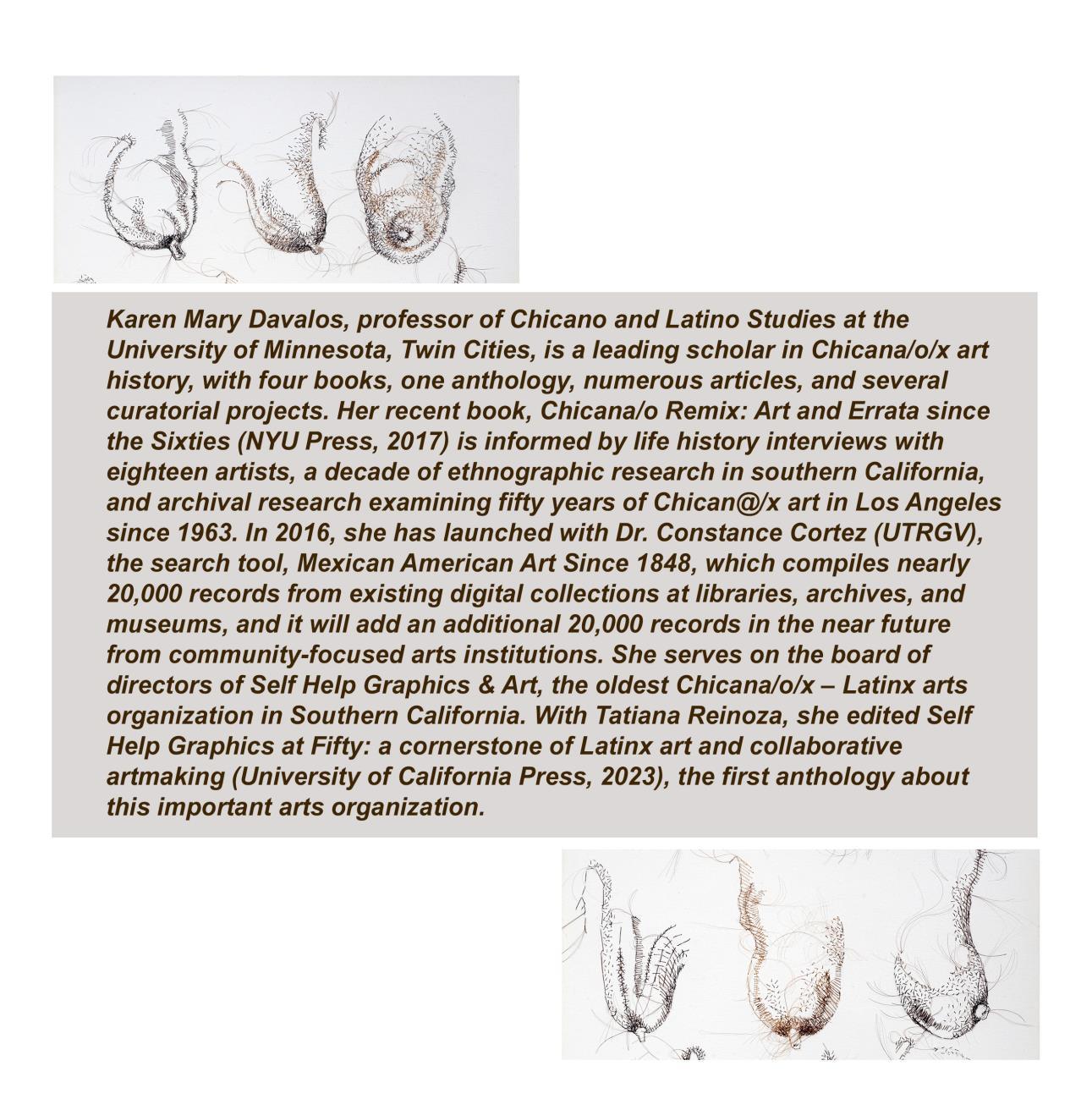

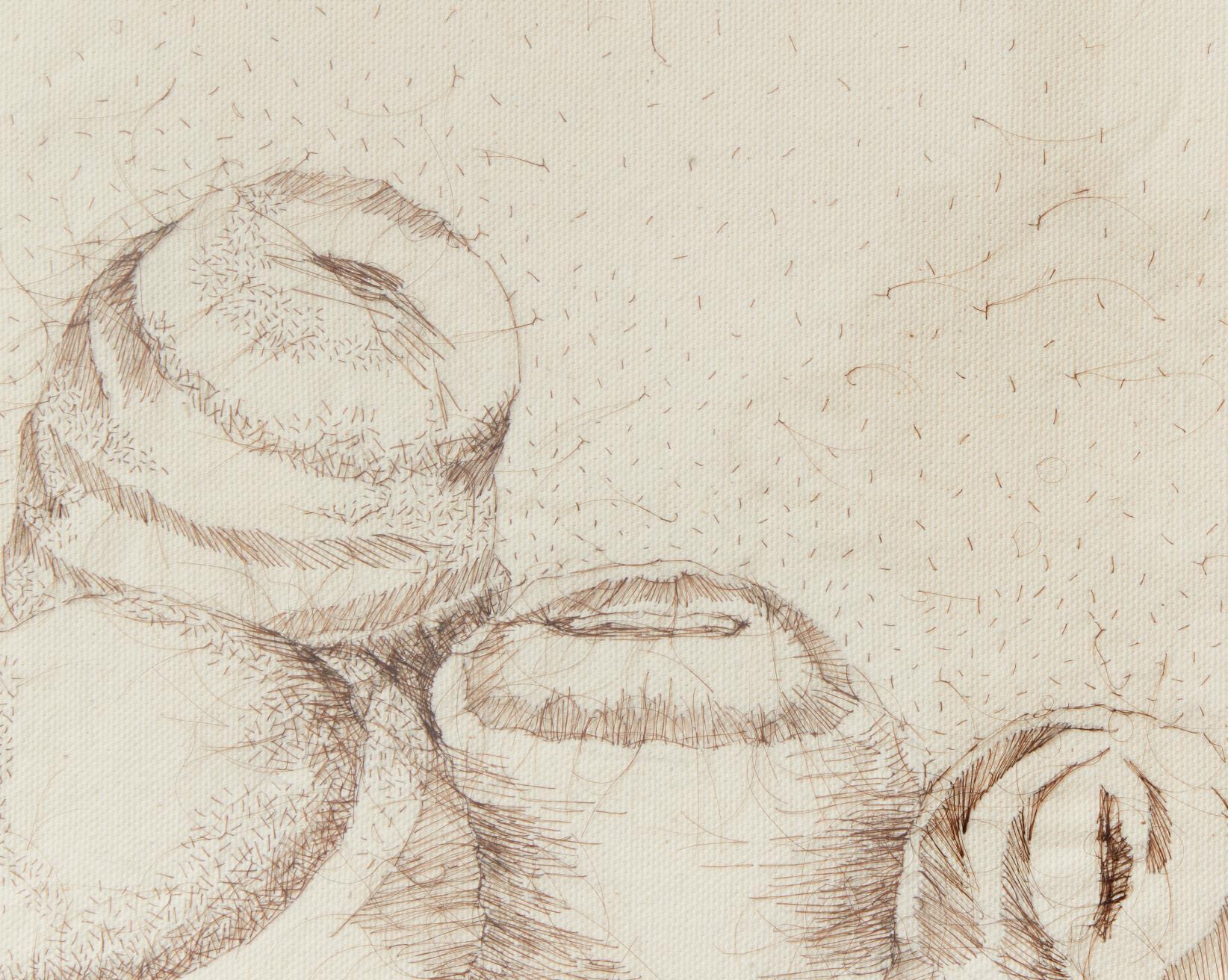

The questioning is found in another series devoted to the female body, equally significant for its nepantla aesthetics. In the series Body Image, Meza-DesPlas frequently creates compositions of discrete body parts, namely breasts and buttocks, supporting a different kind of looking at the fetishized and sexualized parts of female bodies: breasts and buttocks. Although heteropatriarchy is hyper focused on these body parts as noted above, Meza-DesPlas’s treatment of breasts and butts is funny, even satirical, and this playfulness, I propose, activates nepantla aesthetics. In the series on Body Image, the artist isolates the breast and the buttock as if to accentuate the hyperfocus of heteropatriachal gazing, but the forms are so decontextualized that they become abstract. Images made of Handsewn human hair on canvas and watercolor on paper depict an abstracted breast that form organic shapes which make nipples and areola into googly eyes, tails, or domes or other architectural elements that cap a structure. MezaDesPlas further abstracts these parts of the female body by depicting ample breasts and rumps without a single orientation in negative space. In Personages, they float, cluster, or droop without context, arranged as if the body is upside down, sideways, or right side up. She also depicts breasts and buttocks without their pairs, as in Personages and other works in the series. One cheek or one protruding organ from the chest wall is arranged with other singular anatomical parts from other female bodies.

The humorous and satirical visual composition of isolated breasts and buttocks, as well as isolated lower limbs, is social critique of female objectification, even as it doubles the ways in which heteropatriarchal gazing fixates on these body parts. The series oscillates, or depends upon I would venture, the heteropatriarchal relationship to the female breasts and buttocks as anatomical symbols of racialized beauty. It provides precisely what the heteropatriarchal gaze desires, but not exactly in the way it is anticipated or obligated.

The Meza-DesPlas works against the pressures of subordination, erasure, and invisibility, and therefore, I turned to nepantla aesthetics to acknowledge the blending of critique with appropriation of the very thing at the center of her criticism. Meza-DesPlas challenges heteropatriarchy, even as she employs the strategies of heteropatriarchal gazing and objectification. As such, nepantla aesthetics side steps such expectations or stereotyping of “ethnic” art, relishing the unexpected and the unknown, while recognizing the weight of cultural hegemony. It allows viewers to see Meza-DesPlas’s use of her hair as counterhegemonic stance to art world hierarchies that devalue fiber arts and domestic crafts by women of color. It also anticipates her liberatory practice due to the figures’ composition which oscillate between heteropatriarchy and feminist gazing. Even if viewers project stereotypes of Chicana inadequacy onto her work, Meza-DesPlas calls into question racism, sexism, and ageism with her humorous rendering of breasts and buttocks. She provides a vision of hope and joy, and in the case of Personages, a bit of good humor.

Karen Mary Davalos

7

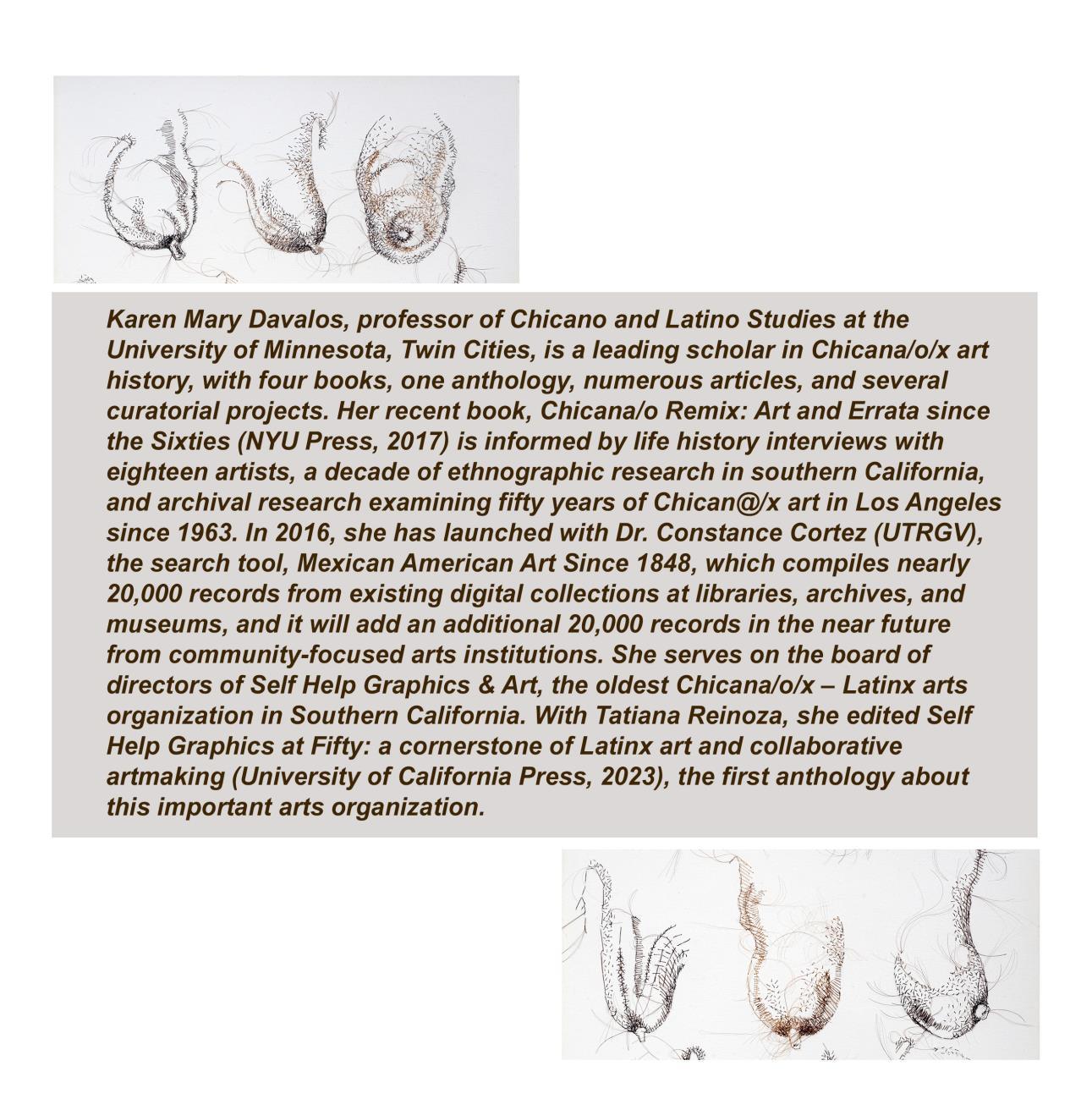

Karen Mary Davalos, professor of Chicano and Latino Studies at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, is a leading scholar in Chicana/o/x art history, with four books, one anthology, numerous articles, and several curatorial projects. Her recent book, Chicana/o Remix: Art and Errata since the Sixties (NYU Press, 2017) is informed by life history interviews with eighteen artists, a decade of ethnographic research in southern California, and archival research examining fifty years of Chican@/x art in Los Angeles since 1963. In 2016, she has launched with Dr. Constance Cortez (UTRGV), the search tool, Mexican American Art Since 1848, which compiles nearly 20,000 records from existing digital collections at libraries, archives, and museums, and it will add an additional 20,000 records in the near future from community-focused arts institutions. She serves on the board of directors of Self Help Graphics & Art, the oldest Chicana/o/x – Latinx arts organization in Southern California. With Tatiana Reinoza, she edited Self Help Graphics at Fifty: a cornerstone of Latinx art and collaborative artmaking (University of California Press, 2023), the first anthology about this important arts organization.

artwork

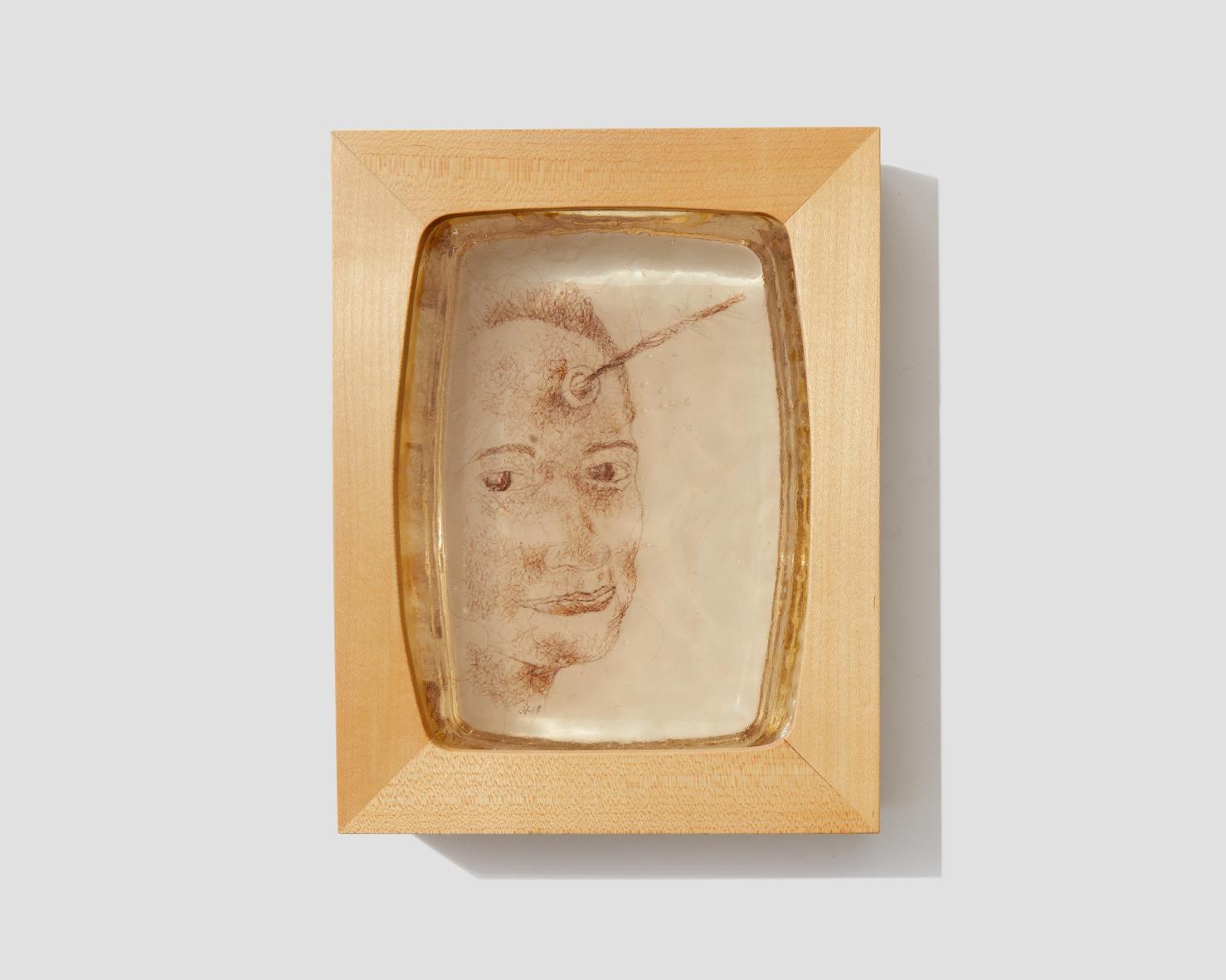

Malcriada, 2001

Hand-sewn human hair with color pencil, graphite and gouache, 13.5 x 13.5 x 1.25 inches

Malcriada, 2001

Hand-sewn human hair with color pencil, graphite and gouache, 13.5 x 13.5 x 1.25 inches

9

Photography by Mariah Richstone

Phyllis & Aristotle, 2001

Hand-sewn human hair with watercolor and color pencils, 19 x 21 x 1.25 inches

Image courtesy of form & concept. Photography by Marylene Mey

10

Hand-sewn human hair on mylar encased in three-layer resin cast, 9 x 7 x 2 inches

concept.

11

Image courtesy of form &

Photography by Marylene Mey

Just a Small Bite (detail)

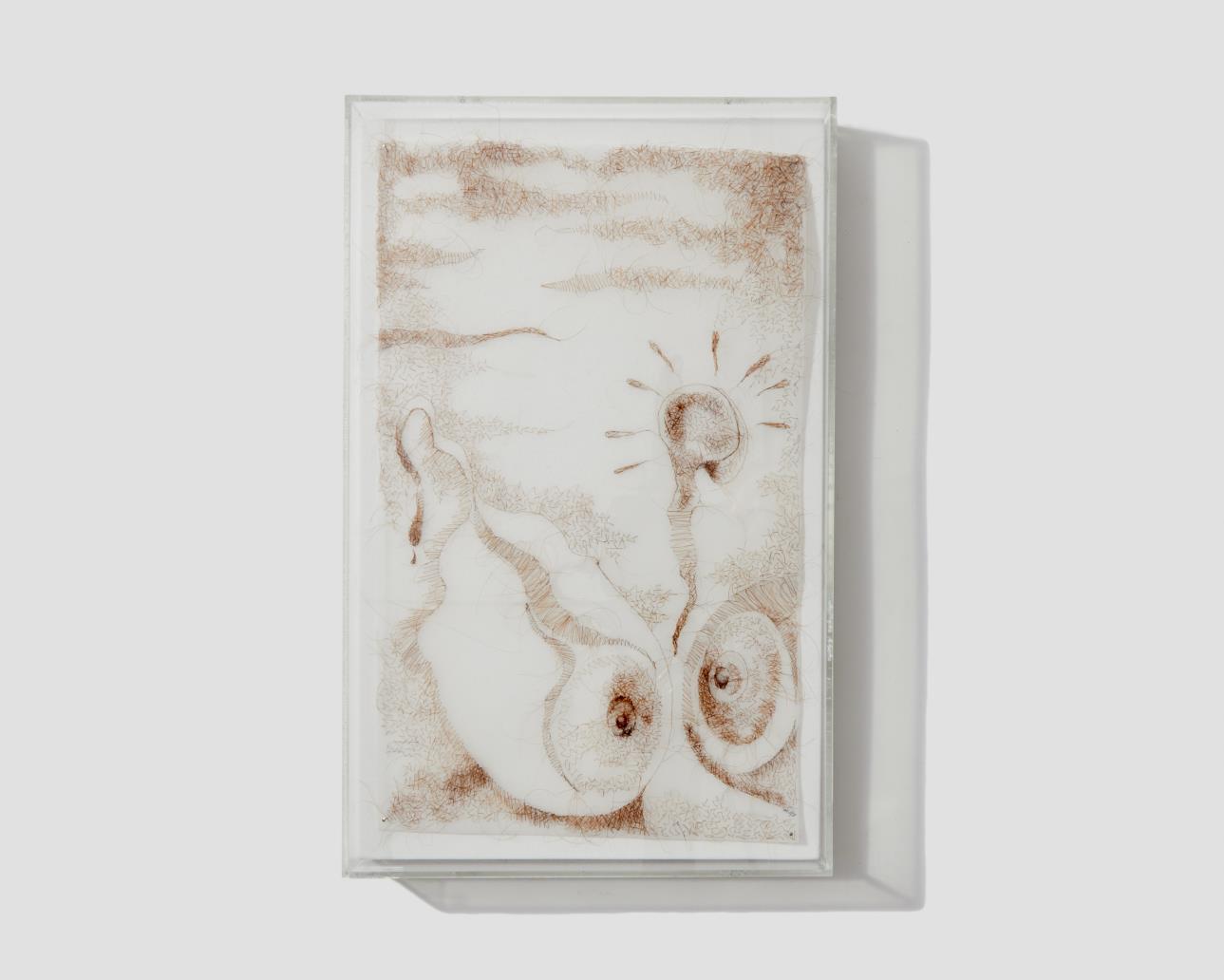

Just a Small Bite, 2004

Hand-sewn human hair embedded in three-layer cast, 12 x 12 x 2 inches, Image courtesy of form & concept. Photography by Marylene Mey

13

14

Hand Photography by Steve Cruz

Bad Thoughts Come and Go, 2005

Hand-sewn human hair on mylar, 14.5 x 9 x 2 inches

Image courtesy of form & concept. Photography by

15

Marylene Mey

The Waiting, 2005

Hand-sewn human hair on mylar, 9.5 x 15 x 2 inches

The Waiting, 2005

Hand-sewn human hair on mylar, 9.5 x 15 x 2 inches

16

Photography by Mariah Richstone

Real, Live, Broken, 2006

Hand-sewn human hair on vellum, 20 x 16 x 1.5 inches

Real, Live, Broken, 2006

Hand-sewn human hair on vellum, 20 x 16 x 1.5 inches

17

Image courtesy of form & concept. Photography by Marylene Mey

Real, Live, Broken (detail)

Real, Live, Broken (detail)

Real, Live, Broken (detail)

Real, Live, Broken (detail)

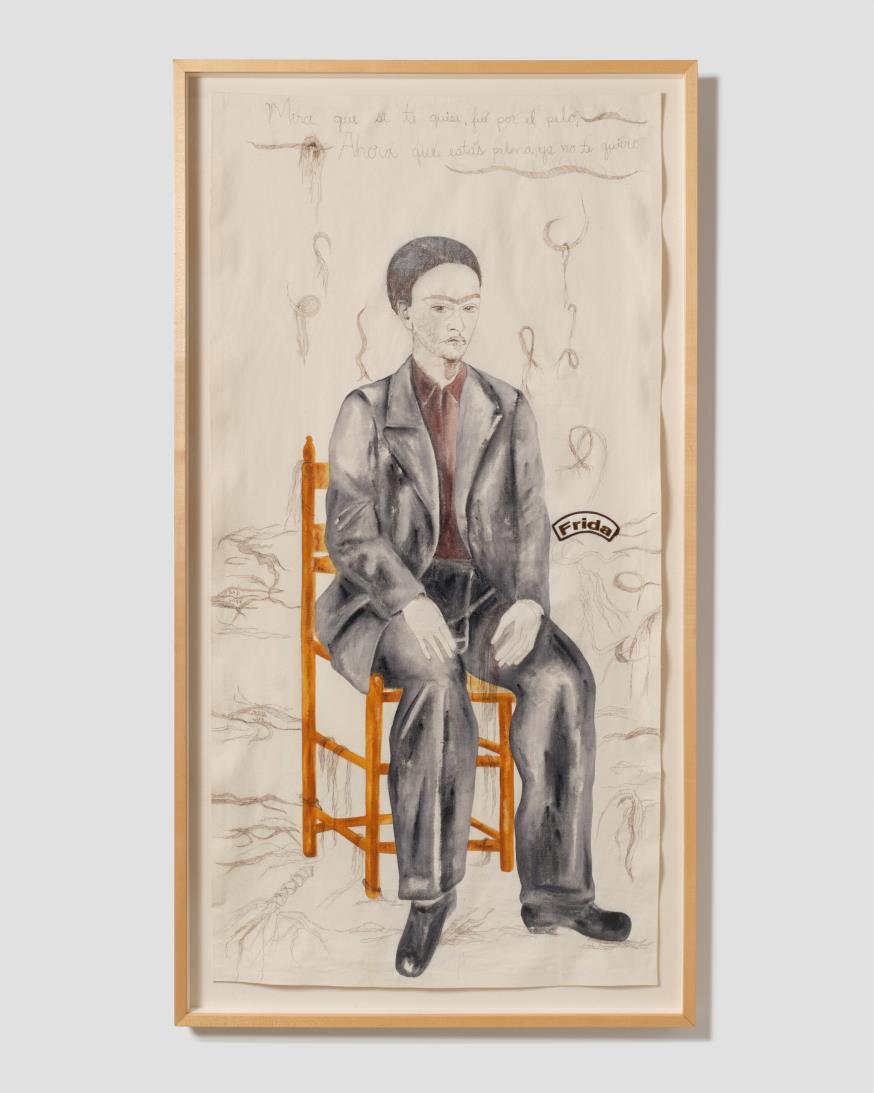

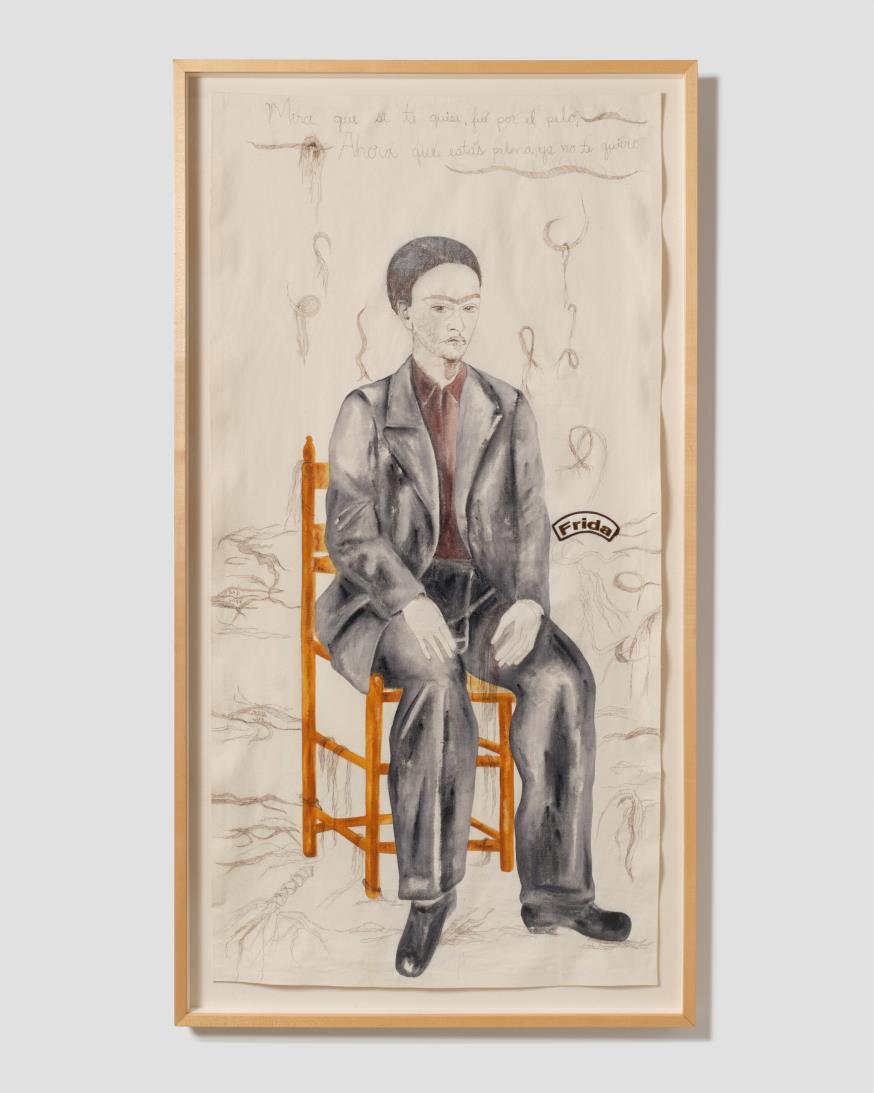

34th Floor, 2007

Hand-sewn human hair, watercolor and patch on unprimed canvas, 60.5 x 29 x 2.25 inches Image courtesy of form & concept. Photography by Byron Flesher

20

Everything Has Changed, 2007

Hand-sewn human hair with patch on unprimed canvas, 11.5 x 11.5 x 1.5 inches

Everything Has Changed, 2007

Hand-sewn human hair with patch on unprimed canvas, 11.5 x 11.5 x 1.5 inches

21

Image courtesy of form & concept. Photography by Marylene Mey

Hand-sewn human hair with watercolor and patch on unprimed canvas, 63 x 33 x 2.25 inches Image courtesy of form & concept. Photography by Byron Flesher

Steady as She Goes, 2007

22

Wasn’t I Always a Friend To You, 2007

Hand-sewn human hair with acrylic and patch, 67.5 x 32 x 2.25 inches

Wasn’t I Always a Friend To You, 2007

Hand-sewn human hair with acrylic and patch, 67.5 x 32 x 2.25 inches

23

Image courtesy of form & concept. Photography by Byron Flesher

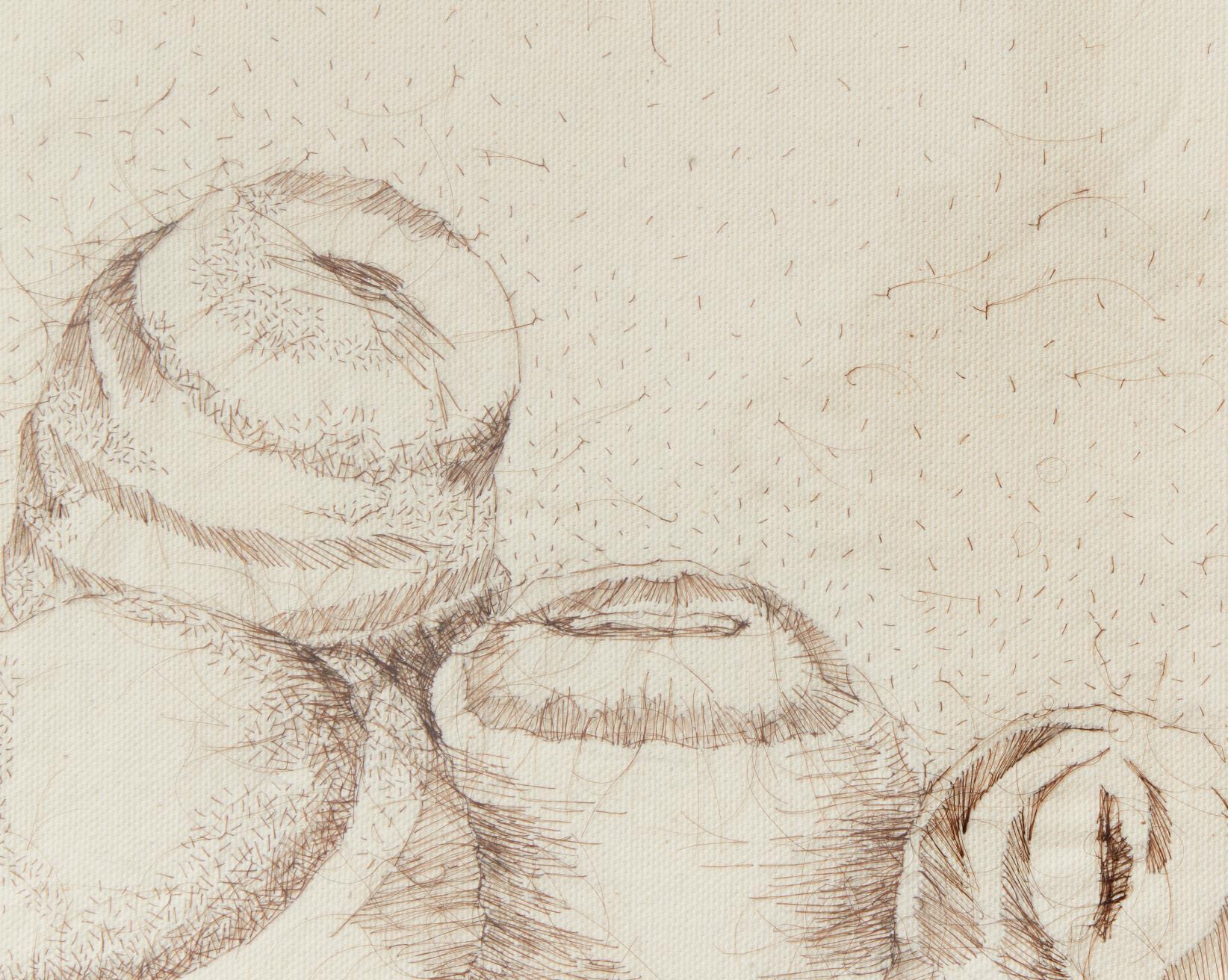

Animal (detail)

Real

Real Animal, 2008

Hand-sewn human hair on unprimed canvas, 17 x 18 x 1.5 inches

Real Animal, 2008

Hand-sewn human hair on unprimed canvas, 17 x 18 x 1.5 inches

25

Image courtesy of form & concept. Photography by Marylene Mey

Real Animal (detail)

Real Animal (detail)

Lee’s Dream, 2009

Hand-sewn human hair on unprimed canvas, 19 x 15 x 1.5 inches

Lee’s Dream, 2009

Hand-sewn human hair on unprimed canvas, 19 x 15 x 1.5 inches

27

Photography by Harrison Evans

The Good Body, 2010

Hand-sewn human hair on unprimed canvas, 31 x 16 x 2.5 inches

The Good Body, 2010

Hand-sewn human hair on unprimed canvas, 31 x 16 x 2.5 inches

28

Photography by Harrison Evans

Personages, 2011

Hand-sewn human hair on primed watercolor canvas, 13.25 x 10.25 x 2.25 inches

29

Photography by Harrison Evans

Jiggle, Jiggle, Jiggle, 2012

Hand-sewn human hair on primed oil canvas, 13 x 13 x 2 inches

Jiggle, Jiggle, Jiggle, 2012

Hand-sewn human hair on primed oil canvas, 13 x 13 x 2 inches

30

Photography by Harrison Evans

Cry, Die or Just Make Pies, 2013

Hand-sewn human hair on primed watercolor canvas, 15.25 x 12.25 x 2 inches

31

Photography by Harrison Evans

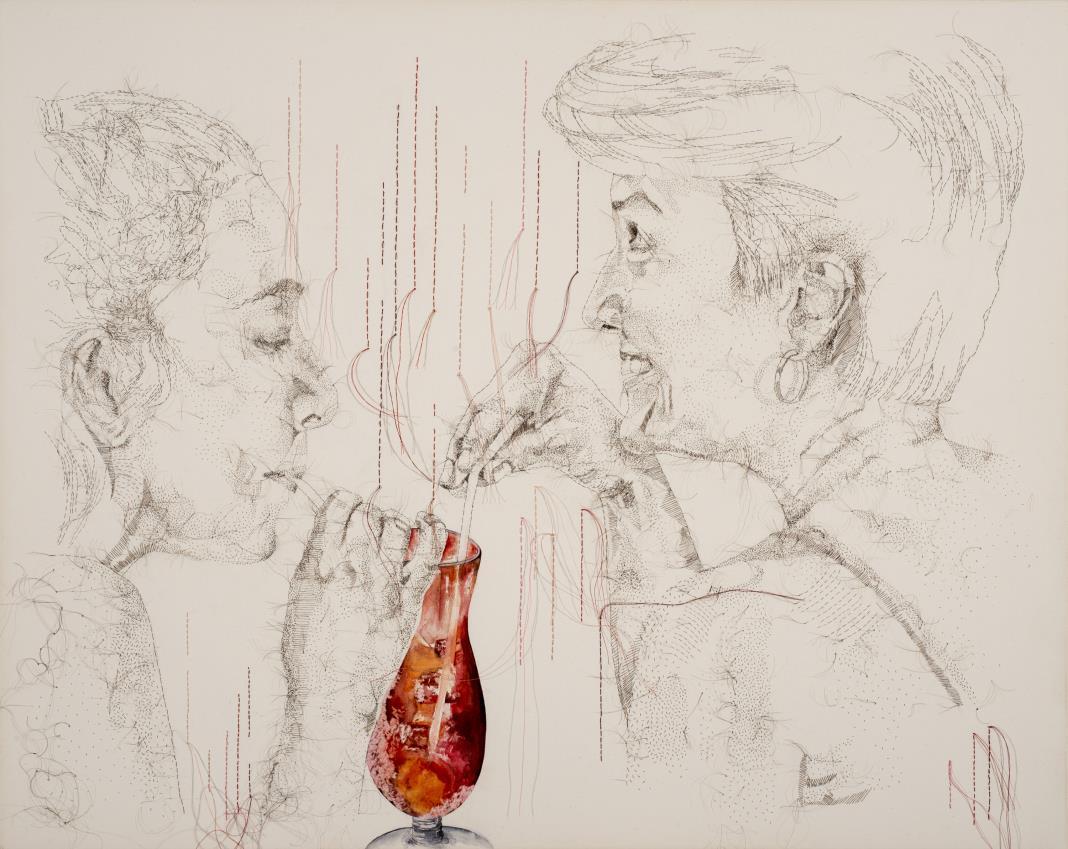

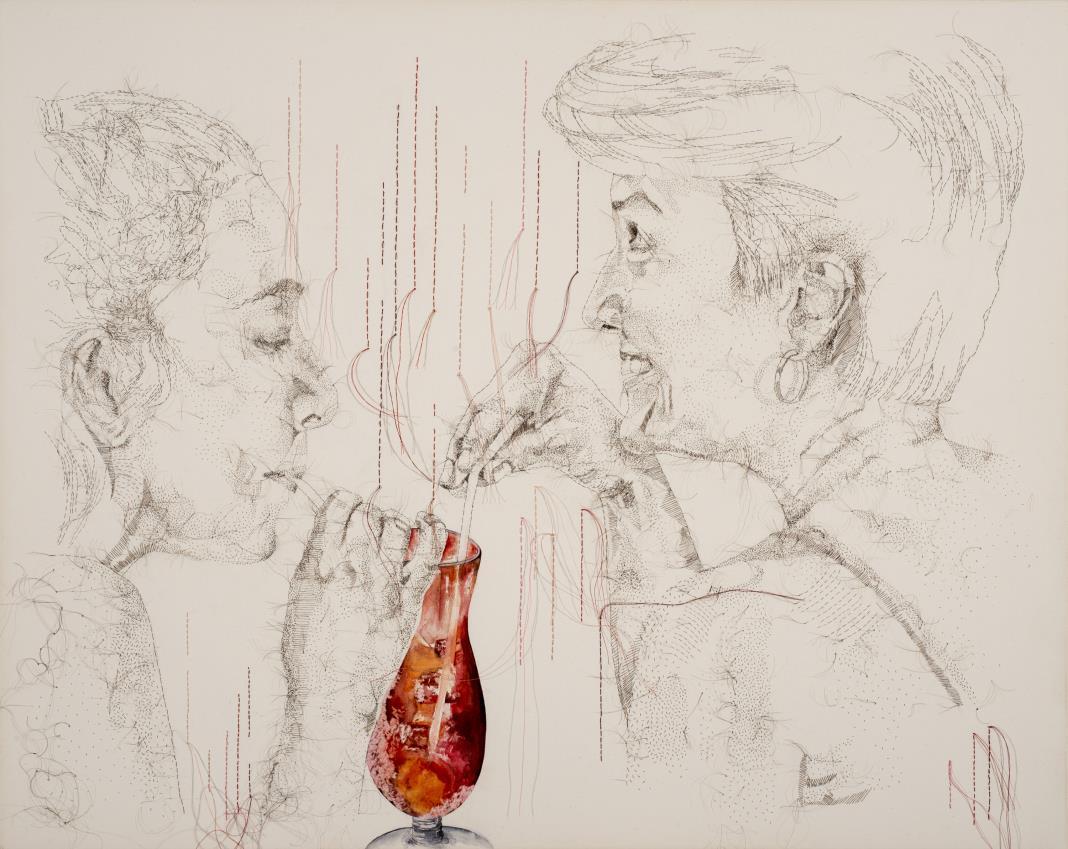

Peck not Prick, 2014

Hand-stitched human hair on primed watercolor canvas, 25.5 x 31.5 x 2.25 inches

Peck not Prick, 2014

Hand-stitched human hair on primed watercolor canvas, 25.5 x 31.5 x 2.25 inches

32

Photography by Harrison Evans

One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer, 2015 Hand-sewn human hair with thread and watercolor accent on watercolor canvas, 25.25 x 31 x 2.25 inches

One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer, 2015 Hand-sewn human hair with thread and watercolor accent on watercolor canvas, 25.25 x 31 x 2.25 inches

33

Photography by Harrison Evans

One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer (detail)

One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer (detail)

One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer (detail)

One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer (detail)

I’m Your Green Honeycreeper, Baby, 2015

Hand-sewn human hair and thread with watercolor and collage on watercolor canvas, 25.25 x 31.25 x 2.25 inches

I’m Your Green Honeycreeper, Baby, 2015

Hand-sewn human hair and thread with watercolor and collage on watercolor canvas, 25.25 x 31.25 x 2.25 inches

36

Photography by Harrison Evans

I’m the Wilderness, I’m the White Noise, 2016 Hand-sewn human hair with watercolor on stretched watercolor canvas, 12 x 15 x 2.25 inches

I’m the Wilderness, I’m the White Noise, 2016 Hand-sewn human hair with watercolor on stretched watercolor canvas, 12 x 15 x 2.25 inches

37

Photography by Harrison Evans

Ancestry of Anger, 2016-2018

Hand-sewn human hair on fabric, mounted on twenty round stretched canvasses 8 inch diameter each, 60 x 48 inches installed

38

Photography by Mariah Richstone

Hand sewn human hair with thread and watercolor on watercolor canvas, 13.5 x 10.5 x 1.25 inches

39

What You Whispered, Should Be Screamed (detail)

What You Whispered, Should Be Screamed, 2018

Hand-sewn human gray hair on black twill fabric, 33.25 x 35 x 2.25 inches

What You Whispered, Should Be Screamed, 2018

Hand-sewn human gray hair on black twill fabric, 33.25 x 35 x 2.25 inches

41

Photography by Mariah Richstone

Time Will Do The Talking, 2018

Hand-sewn human hair on stretched watercolor canvas, 17.25 x 13.25 x 2 inches

Time Will Do The Talking, 2018

Hand-sewn human hair on stretched watercolor canvas, 17.25 x 13.25 x 2 inches

42

Image courtesy of form & concept. Photography by Marylene Mey

Twelve Angry Women, 2018

Hand-sewn human gray hair on black twill fabric, 20.5 x 20.5 x 2.5 inches

Twelve Angry Women, 2018

Hand-sewn human gray hair on black twill fabric, 20.5 x 20.5 x 2.5 inches

43

Photography by Mariah Richstone

Agency #1, 2019

Hand-sewn human gray hair on black twill fabric, 11.25 x 11.75 x 2.25 inches

Agency #1, 2019

Hand-sewn human gray hair on black twill fabric, 11.25 x 11.75 x 2.25 inches

44

Photography by Mariah Richstone

Marching Across Your Lawn, The Grass is On Fire, 2020 Hand-sewn human hair on black twill fabric, 32 x 37 x 2.25 inches

Marching Across Your Lawn, The Grass is On Fire, 2020 Hand-sewn human hair on black twill fabric, 32 x 37 x 2.25 inches

45

Photography by Mariah Richstone

Jane Marches #1 (detail)

Jane Marches #1 (detail)

Hand-sewn human hair, watercolor washes, fabric, thread and appliques, unprimed and unstretched canvas, bra straps are the hanging device, 60 x 36 x .25 inches

Jane Marches #1, 2020

47

Photography by Mariah Richstone

Hand-sewn human hair, gesso, conte, fabric, thread and appliques, unprimed and unstretched canvas, bra straps are the hanging device, 61 x 39.5 x .25 inches

Image courtesy of form & concept. Photography by Byron Flesher

Jane Marches #2, 2021

48

49

Rosemary Meza-DesPlas, a multidisciplinary Latina/Coahuiltecan artist, incorporates fiber art, drawing, installation, painting, performance art, and video into her studio practice. The human figure takes center stage in her artwork. Amplifying the voices of women, her work reflects the female experience within a patriarchal society. Socio-cultural issues, gender-based burdens, political agency, and ethnic stereotypes, are explored through an intersectional feminist lens. The tenacity of her eight aunts in the face of personal tragedies and adversities was an early inspiration; their narratives contributed to her embrace of feminist ideology. Thematic continuity links Meza-DesPlas’ visual artwork with her academic writing and poetry. This written discourse provides a foundation for her performance artwork. In 2022, she was honored with a Latinx Artist Fellowship by the Mellon Foundation and the Ford Foundation. She was awarded a Fulcrum Fund grant in 2022 to create and stage a new performance artwork titled Miss Nalgas USA 2022. Her work has been exhibited at Museum of Sonoma County, 516 ARTS, New Mexico Museum of Art, and Art Museum of Southeast Texas. Meza-DesPlas received a BFA from the University of North Texas and an MFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art.

Artist Statement

As a multidisciplinary artist, I create figurative artworks exploring gender issues, political agency, and cultural misconceptions. Challenging beauty standards, the feminine body is portrayed with attention to veracity. Portraiture work emphasizes the mutable nature of a face. My studio practice varies from labor intensive hand-stitched hair art to large on-site, multimedia installations.

Feminism and ethnicity are referenced in a common material, human hair, employed in my studio practice. I sew with the first fiber: hair. My sewing can be contextualized within the 1970s women’s craft movement, yet I stitch hair from a drawing-based background. The hair serves as an archive of my body and reflects the aging process. A carrier of DNA, hair symbolizes ethnicity and race.

Identity and culture manifest in my traditional art forms of painting, drawing, and sculpture. Through appropriation, these traditional media works are reinvented into specialty fabrics and embedded into performance art and video. Arranged smaller artworks create sizable installations.

I forefront myself in performance art and video works; thereby, alluding to the multiplex experience of being an American, Indigenous, Latina woman. My poetry anchors the performance art and video works. Academic research and writings reinforce thematic inquiries into gender topics, socio-political issues, and cultural stereotypes.

50

Malcriada, 2001

Hand-sewn human hair, color pencil, graphite and gouache

13.5” x 13.5” x 1.25”

Phyllis & Aristotle, 2001

Hand-sewn human hair with watercolor and color pencils

19” x 21” x 1.25”

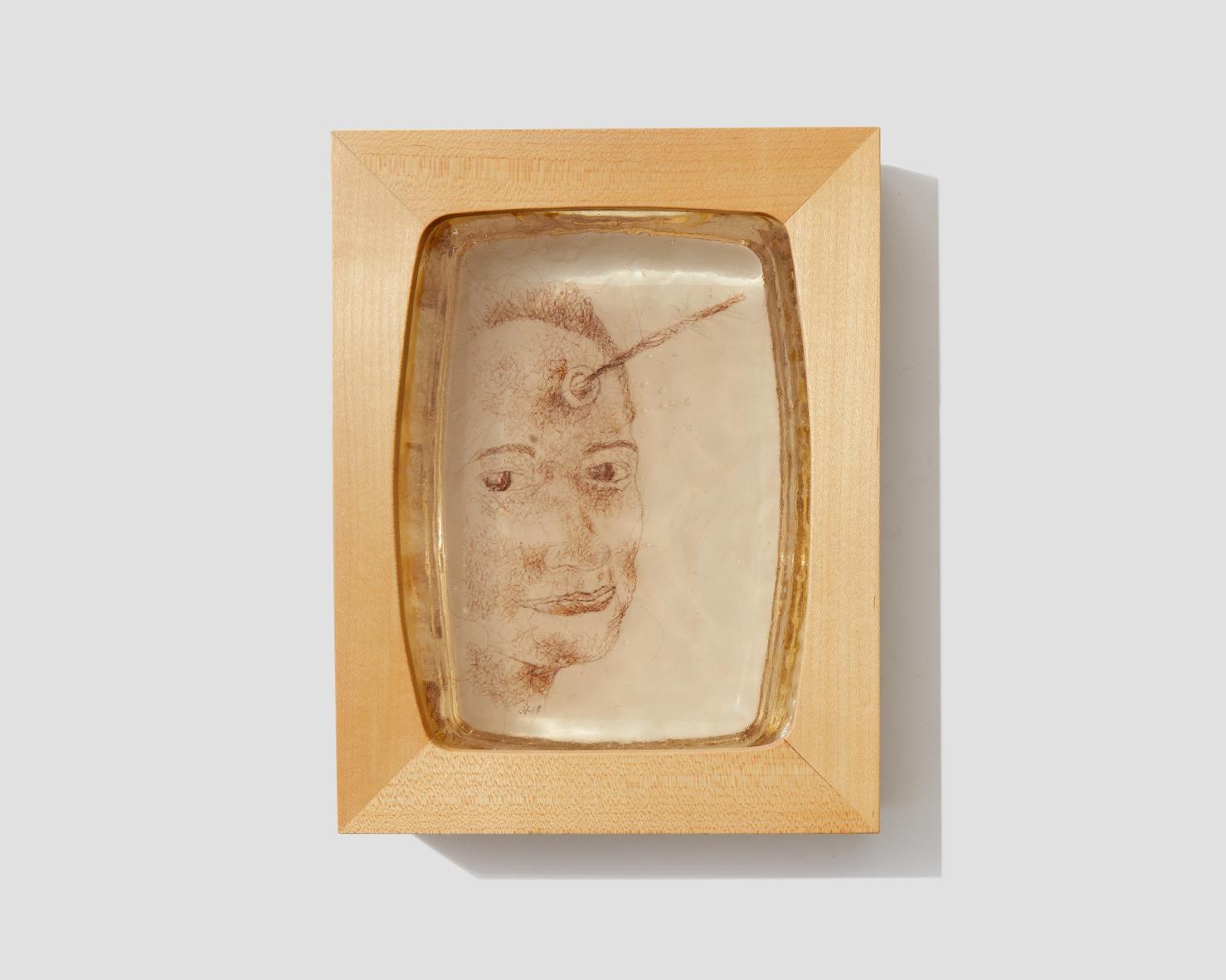

You Need Another Lover Like a Hole in Your Head, 2004

Hand-sewn human hair on mylar encased in 3-layer resin cast, 9” x 7” x 2”

Swallow the Love, Spit Out the Seed, 2004

Hand-sewn human hair with color pencil and watercolor

16.5” x 16.5” x 1.25”

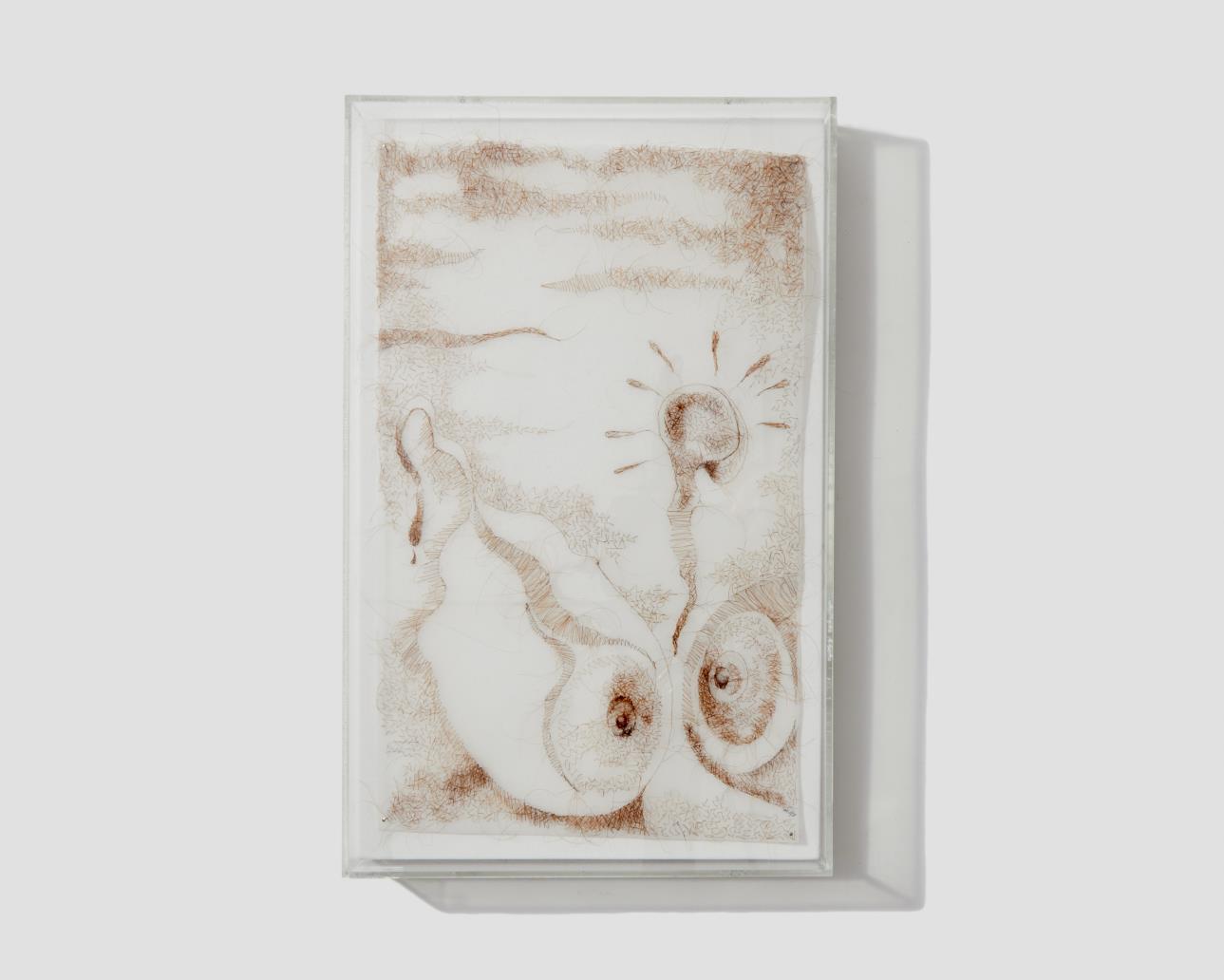

Just a Small Bite, 2004

Hand-sewn human hair embedded in 3-layer cast 12” x 12” x 2”

Bad Thoughts Come and Go, 2005

Hand-sewn human hair on mylar, 14.5” x 9” x 2”

The Waiting, 2005

Hand-sewn human hair on mylar

9.5” x 15” x 2”

Checklist

of the Exhibition

Real, Live, Broken, 2006

Hand-sewn human hair on vellum 20” x 16” x 1.5”

Everything Has Changed, 2007

Hand-sewn human hair with patch on unprimed canvas

11.5” x 11.5” x 1.5”

34th Floor, 2007

Hand-sewn human hair, watercolor and patch on unprimed canvas, 60.5” x 29” x 2.25”

Steady as She Goes, 2007

Hand-sewn human hair with watercolor and patch on unprimed canvas, 63” x 33” x 2.25”

Wasn’t I Always a Friend To You, 2007, Hand-sewn human hair with acrylic and patch, 67.5” x 32” x 2.25”

Real Animal, 2008

Hand-sewn human hair on unprimed canvas, 17” x 18” x 1.5”

Lee’s Dream, 2009

Hand-sewn human hair on unprimed canvas, 19” x 15” x 1.5”

The Good Body, 2010

Hand-sewn human hair on unprimed canvas, 31” x 16” x 2.5”

Personages, 2011

Hand-sewn human hair on primed watercolor canvas

13.25” x 10.25” x 2.25”

Jiggle, Jiggle, Jiggle, 2012

Hand-sewn human hair on primed oil canvas, 13” x 13” x 2”

Cry, Die or Just Make Pies, 2013

Hand-sewn human hair on primed watercolor canvas, 15.25” x 12.25” x 2”

Peck not Prick, 2014

Hand-stitched human hair on primed watercolor canvas

25.5” x 31.5” x 2.25”

One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer, 2015, Hand-sewn human hair with thread, watercolor accent on watercolor canvas 25.25” x 31” x 2.25”

I’m Your Green Honeycreeper, Baby, 2015, Hand-sewn human hair and thread with watercolor and collage on watercolor canvas

25.25” x 31.25” x 2.25”

I’m the Wilderness, I’m the White Noise, 2016, Hand-sewn human hair with watercolor on stretched watercolor canvas, 12” x 15” x 2.5”

51

Ancestry of Anger, 2016-2018

Hand-sewn human hair on fabric, mounted on twenty round stretched canvasses, 8” diameter each, 60” x 48” installed

Emma Sulkowicz #1, 2017

Hand-sewn human hair with thread and watercolor on watercolor canvas, 13.5” x 10.5” x 1.25”

Time Will Do The Talking, 2018

Hand-sewn human hair on stretched watercolor canvas 17.25” x 13.25” x 2”

What You Whispered, Should Be Screamed, 2018

Hand-sewn human gray hair on black twill fabric, 33.25” x 35” x 2.25”

Twelve Angry Women, 2018

Hand-sewn human gray hair on black twill fabric, 20.5” x 20.5” x 2.5”

Agency #1, 2019

Hand-sewn human gray hair on black twill fabric 11.75” x 11.75” x 2.25”

Jane Marches #1, 2020

Hand-sewn human hair, watercolor washes, fabric, thread and appliques, unprimed and unstretched canvas, bra straps are the hanging device, 60” x 36” x .25”

Marching Across Your Lawn, The Grass is On Fire, 2020

Hand-sewn human hair on black twill fabric, 32” x 37” x 2.25”

Jane Marches #2, 2021

Hand-sewn human hair, gesso, conte, fabric, thread and appliques, unprimed and unstretched canvas, bra straps are the hanging device, 61” x 39.5” x.25”

Graces, Nalgonas, Marias 2022-2023, Hand-sewn human gray hair, specialty fabric with thread on black twill fabric 34” x 38” x 2.25”

52

EDUCATION:

ROSEMARY MEZA-DESPLAS

4405 Sandia Ct Farmington, New Mexico * 972-358-1670

rosemarymeza333@yahoo.com

https://www.rosemarymeza.com/ http://rosemarymezadesplas.com

MFA. 1990 Hoffberger School of Painting

BFA. 1988 Painting/Drawing

AWARDS:

Maryland Institute, College of Art

University of North Texas

2022 Latinx Artist Fellowship, The Mellon Foundation and the Ford Foundation, administered by US Latinx Art Forum in collaboration with the New York Foundation for the Arts

Fulcrum Fund Grant, 516 ARTS in partnership with The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and Frederick Hammersley Fund for the Arts at the Albuquerque Community Foundation

SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITS:

2026 Solo Exhibition, Martin Museum of Art, Waco, TX

2024 My Hair Story: from Brunette to Gray, form & concept gallery, Santa Fe, NM

2023 La Tercera y Última: Miss Nalgas USA, Amos Eno Gallery, Brooklyn, NY

SELECTED GROUP MUSEUM EXHIBITS:

2022 Agency: Feminist Art and Power, Museum of Sonoma County, Santa Rosa, CA (curated by Karen Gutfreund, independent curator) (catalog)

Femina, Spartanburg Art Museum, Spartanburg, SC (curated by Elizabeth Goddard, Director of Spartanburg Art Museum)

2020 Feminisms, 516 Arts, Albuquerque, NM (curated by Andrea Hanley, Chief Curator Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian) (catalog)

SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITS:

2023 Bodies, Bodies, Bodies: raffish vulnerability and profane ambivalence, Pen + Brush Gallery, NYC, NY (curated by Parker Daley Garcia)

Embodied Knowledge, Ely Center of Contemporary Art, New Haven, CT (curated by nico w. okoro)

2022 Manufactured Narratives, Urban Institute for Contemporary Arts, Grand Rapids, MI (curated by Juana Williams)

2021 Unraveled: Confronting the Fabric of Fiber Art, The Untitled Space, NYC, NY (curated by Indira Cesarine)

Deadlocked and Loaded: Disarming America, ArtRage Gallery, Syracuse, NY (curated by Karen M. Gutfreund, independent curator)

2020 Currents: An Overwhelming Response, AIR Gallery, Brooklyn, NY (curated by Carmen Hermo, Assoc.

Curator @ Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art)

53

Hairstory, artspace, Raleigh, NC (curated by Annah Lee)

Crisis Mode, Orange County Center for Contemporary Art, Santa Ana, CA (curated by Lucia Olubunmi Momoh, independent curator)

2019 Fahrenheit 213, Arc Gallery, San Francisco, CA (lead curator, Tanya Augsburg, Professor of Humanities and Liberal Studies, San Francisco State University) (catalog) 12 New Mexico Artists to Know Now, The Magazine Project Space, Santa Fe, NM

RESIDENCIES:

2024 Apapacho Residency, Mexico City, Mexico

2023 Ucross Residency, Ucross, Wyoming

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Maximilíano Durón, The Year in Latinx Art: Icons Receive Their Due as Mid-Career and Emerging Artists Get Spotlights, ARTnews, December 29, 2023.

Scotti Hill, Feature article Medium + Support, Southwest Contemporary, Vol. 8 Fall-Winter 2023.

Molly Boyle, The Body, Political, New Mexico magazine, October 2022.

Maximilíano Durón, Ford, Mellon Foundations Name 2022 Winners of $50,000 Latinx Artist Fellowships, Including Amalia Mesa-Bains, Las Nietas de Nonó, ARTNews, May 12, 2022.

Lauren Tresp, “12 New Mexico Artists to Know Now: Rosemary Meza-DesPlas”, the/magazine, February/March 2019.

ONLINE PERIODICALS:

Rachel Hodin, “What One Year of Resistance Looks Like in the Art World”, Interview Magazine, January 23, 2018. https://www.interviewmagazine.com/art/one-year-resistance-looks-like-art-world Berette Macaulay, “Rosemary Meza-DesPlas: The Dangerous Seduction of Women with Guns”, Of Note Magazine where art meets activism, The Gun Issue, Summer 2017. http://www.ofnotemagazine.org/2017/06/17/10937/ Joseph Erbentraut, “Artist Hand-Sews Her Own Hair to Create Lavish, Haunting Drawings”, HuffPost Arts & Culture, March 12, 2015, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/03/11/rosemary-meza-desplas-drawings_n_6850000.html

PODCASTS:

Peter Hay, Aquí&Allá: Conversaciones con creadores de MX & EU, PROArtes México, May 5, 2020, https://anchor.fm/ proartes-mex/episodes/Episode-1-1-with-Rosemary-Meza-DesPlas-edhkep

SELECTED LECTURES & PANELS:

2023 X as Intersection: Diasporic Legacies, Latinx Artists in Conversation, A series featuring the cohort of the Latinx Artist Fellowship, April.

At The Intersection: Latinx Art Worlds 2023 Convening, March 2023. Women and Weaving: Textiles, Community, Art, Panel, CAA conference, February. 2022 Latinx Bodies: Presence/absence and representation, Panel, CAA conference, February. 2021 Relishing Wrinkles and Rolls: Bucking Beauty Norms in the Global Art World, Panel, CAA Conference, Virtual Conference, February.

54

PUBLICATIONS AS AUTHOR:

2023 Fulcrum Fund 2018-19/2022-23 catalog, 516 ARTS, essay Sustaining Contemporary Creative Visionaries

2018 International Journal on the Image, Volume 9, Issue 3

2016 International Journal on the Image, Volume 7, Issue 2

SELECTED PERFORMANCES:

2022 Miss Nalgas USA 2022, Farmington Civic Center, Farmington, NM

Spandex Bodies & Identity Cheerleaders, Connie Gotsch Theater, San Juan College

SELECTED VIDEO SCREENINGS:

2024 Performance in Flux, Video as Performance, Colour Senses Project, Miami, FL

XicanIndie Film Fest XXVI, Su Teatro Cultural & Performing Art Center, Denver, CO

Stirring the Pot: I Don’t Cook, Connie Gotsch Theater, San Juan College

55

Graces, Nalgonas, Marias (detail)

Graces, Nalgonas, Marias (detail)

https://www.dianasolis.com/about,

57

Photo Credit: Diana Solis, Latinx Artist Fellowship recipient 2023

@pilsenita

Malcriada, 2001

Hand-sewn human hair with color pencil, graphite and gouache, 13.5 x 13.5 x 1.25 inches

Malcriada, 2001

Hand-sewn human hair with color pencil, graphite and gouache, 13.5 x 13.5 x 1.25 inches

The Waiting, 2005

Hand-sewn human hair on mylar, 9.5 x 15 x 2 inches

The Waiting, 2005

Hand-sewn human hair on mylar, 9.5 x 15 x 2 inches

Real, Live, Broken, 2006

Hand-sewn human hair on vellum, 20 x 16 x 1.5 inches

Real, Live, Broken, 2006

Hand-sewn human hair on vellum, 20 x 16 x 1.5 inches

Real, Live, Broken (detail)

Real, Live, Broken (detail)

Real, Live, Broken (detail)

Real, Live, Broken (detail)

Everything Has Changed, 2007

Hand-sewn human hair with patch on unprimed canvas, 11.5 x 11.5 x 1.5 inches

Everything Has Changed, 2007

Hand-sewn human hair with patch on unprimed canvas, 11.5 x 11.5 x 1.5 inches

Wasn’t I Always a Friend To You, 2007

Hand-sewn human hair with acrylic and patch, 67.5 x 32 x 2.25 inches

Wasn’t I Always a Friend To You, 2007

Hand-sewn human hair with acrylic and patch, 67.5 x 32 x 2.25 inches

Real Animal, 2008

Hand-sewn human hair on unprimed canvas, 17 x 18 x 1.5 inches

Real Animal, 2008

Hand-sewn human hair on unprimed canvas, 17 x 18 x 1.5 inches

Real Animal (detail)

Real Animal (detail)

Lee’s Dream, 2009

Hand-sewn human hair on unprimed canvas, 19 x 15 x 1.5 inches

Lee’s Dream, 2009

Hand-sewn human hair on unprimed canvas, 19 x 15 x 1.5 inches

The Good Body, 2010

Hand-sewn human hair on unprimed canvas, 31 x 16 x 2.5 inches

The Good Body, 2010

Hand-sewn human hair on unprimed canvas, 31 x 16 x 2.5 inches

Jiggle, Jiggle, Jiggle, 2012

Hand-sewn human hair on primed oil canvas, 13 x 13 x 2 inches

Jiggle, Jiggle, Jiggle, 2012

Hand-sewn human hair on primed oil canvas, 13 x 13 x 2 inches

Peck not Prick, 2014

Hand-stitched human hair on primed watercolor canvas, 25.5 x 31.5 x 2.25 inches

Peck not Prick, 2014

Hand-stitched human hair on primed watercolor canvas, 25.5 x 31.5 x 2.25 inches

One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer, 2015 Hand-sewn human hair with thread and watercolor accent on watercolor canvas, 25.25 x 31 x 2.25 inches

One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer, 2015 Hand-sewn human hair with thread and watercolor accent on watercolor canvas, 25.25 x 31 x 2.25 inches

One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer (detail)

One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer (detail)

One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer (detail)

One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer (detail)

I’m Your Green Honeycreeper, Baby, 2015

Hand-sewn human hair and thread with watercolor and collage on watercolor canvas, 25.25 x 31.25 x 2.25 inches

I’m Your Green Honeycreeper, Baby, 2015

Hand-sewn human hair and thread with watercolor and collage on watercolor canvas, 25.25 x 31.25 x 2.25 inches

I’m the Wilderness, I’m the White Noise, 2016 Hand-sewn human hair with watercolor on stretched watercolor canvas, 12 x 15 x 2.25 inches

I’m the Wilderness, I’m the White Noise, 2016 Hand-sewn human hair with watercolor on stretched watercolor canvas, 12 x 15 x 2.25 inches

What You Whispered, Should Be Screamed, 2018

Hand-sewn human gray hair on black twill fabric, 33.25 x 35 x 2.25 inches

What You Whispered, Should Be Screamed, 2018

Hand-sewn human gray hair on black twill fabric, 33.25 x 35 x 2.25 inches

Time Will Do The Talking, 2018

Hand-sewn human hair on stretched watercolor canvas, 17.25 x 13.25 x 2 inches

Time Will Do The Talking, 2018

Hand-sewn human hair on stretched watercolor canvas, 17.25 x 13.25 x 2 inches

Twelve Angry Women, 2018

Hand-sewn human gray hair on black twill fabric, 20.5 x 20.5 x 2.5 inches

Twelve Angry Women, 2018

Hand-sewn human gray hair on black twill fabric, 20.5 x 20.5 x 2.5 inches

Agency #1, 2019

Hand-sewn human gray hair on black twill fabric, 11.25 x 11.75 x 2.25 inches

Agency #1, 2019

Hand-sewn human gray hair on black twill fabric, 11.25 x 11.75 x 2.25 inches

Marching Across Your Lawn, The Grass is On Fire, 2020 Hand-sewn human hair on black twill fabric, 32 x 37 x 2.25 inches

Marching Across Your Lawn, The Grass is On Fire, 2020 Hand-sewn human hair on black twill fabric, 32 x 37 x 2.25 inches

Jane Marches #1 (detail)

Jane Marches #1 (detail)

Graces, Nalgonas, Marias (detail)

Graces, Nalgonas, Marias (detail)