ISSUE 8

DOWN TO EARTH

How Hayley Morris is transforming her family's country estate into a launchpad for regeneration.

How Hayley Morris is transforming her family's country estate into a launchpad for regeneration.

As the Australian summer winds down and we switch gears to usher in the AFL season and welcome the roar of F1 engines, this might be the perfect time to consider where life will take us in the coming months; a time to ask: “where to next?”

Over the years, my fascination has often been stirred by the untold stories sitting behind the professional successes and private victories of those I have supported through a momentous relocation or lifestyle transition. There is something endlessly intriguing about how people get to where they are. Perhaps it’s seeing the progression of a career marked by obstacles, the advancement of a brilliant idea, or the often emotionally complex process of business succession. Whatever the path, it is always inspiring to hear about the meetings, experiences and coincidences that spark, shape and sustain the journeys of ambitious individuals.

Our cover story features Melbourne businesswoman and philanthropist Hayley Morris, who has successfully channelled her commercial nous, altruistic instinct and expertise in sustainability to reimagine the family business—and create lasting change through regenerative agriculture (p32).

Elsewhere in this edition, we speak with Silicone Valley-based Australian entrepreneur Tim Kentley Klay about autonomous transport solutions for rapidly swelling cities (p30); meet Hui He, the Chinese-born vocalist who has blazed an unlikely trail to eminence on opera’s world stage (p58); and hear from the architect behind the $55m rebirth of Kangaroo Island’s iconic Southern Ocean Lodge (p18).

En route, we stop by the Sydney base of art-loving fashion designer Amber Symond, whose hand-finished garments incorporate elements of portraiture and rock music (p22); quiz furniture designer Henry Wilson about his passage to luxury through quietness and space (p54); and unpack the treasures of the 35th annual Melbourne Art Fair (p48).

We also visit the home of gallerist Sarah Fletcher to learn how she creates fruitful connections between artists and collectors (p13); discover how Flight Centre co-founder Geoff Harris brings principles of good sportsmanship to private equity investment (p10); and get a rundown of the economic environment from the authorities at NAB Private Wealth.

Turning inward, I’m proud to reflect on a year of tremendous growth for Kay & Burton and look forward to reaffirming our role as the real estate advisor of choice with a compelling autumn pipeline of prestige homes.

I hope these stories serve as encouragement as you contemplate the opportunities of this auspicious Year of the Dragon, perhaps helping you to navigate unconventional paths and emerge with new knowledge.

04 THE SHORTLIST

Functionality meets fine art in a liquid-like mirror, marble-accented lounge suite, and sculptural hallway table.

06 CHASING THE HORIZON

NAB’s Alan Oster and JBWere chief Sally Auld explore logical paths through the twists and turns of the Australian economy and investment environment.

10 LEADING FROM THE FRONT

Businessman and philanthropist Geoff Harris discusses the synergies between sports, social enterprise and the corporate world.

18 ISLAND HOMECOMING

Four years after it was razed by wildfire, Kangaroo Island’s award-winning wilderness lodge is back and better than ever.

30 AHEAD OF THE CURVE

Serial entrepreneur Tim Kentley Klay talks to us from the frontline of the self-driving car revolution.

44 HOME ADVANTAGE

Come behind the scenes of furniture and homewares brand Jardan to see how the family-run firm captures the essence of a relaxed lifestyle.

48 FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION

A guide to Melbourne’s premier art fair, where esteemed modern masters feature alongside rising talent, for serious buyers and curious observers alike.

58 COMMANDING THE STAGE

Begin the Year of the Dragon backstage with Hui He, the Chinese soprano who has become one of the great voices of western opera.

60 OUT AND ABOUT

Explore European film, dine on upscale Korean, unwind at a new wellness destination, and more.

Sydney-based home hardware designer Henry Wilson reflects on the intersection of integrity and tactility in his quest for timelessness. Discover how an unlikely mix of rock ’n’ roll, slow craft and

A step inside the studio of celebrated milliner Tamasine Dale uncovers rare trimmings, treasures, and a taste for tradition.

PERFECTLY PLACED

Meet art advisor Sarah Fletcher, who harnesses a powerful aesthetic instinct to bridge the gap between creators and collectors.

02.

DenHolm Toorak console. Harmonising asymmetry with geometric elegance, this smooth stone console table captures the beauty of organic material and its inherent imperfections. As much sculpture as it is furniture, the piece was envisioned by DenHolm studio founders Steven John Clark and Lars Stoten—listed among Vogue’s top 50 Australian designers in 2022—and hand-carved in Melbourne. Each creation has a unique character thanks to the textural whims of whitewashed South Australian limestone and the idiosyncratic DenHolm approach to furniture-making. From $44,246. den-holm.com

Miminat Designs Borris sofa.

An exemplar of textural contrast, this statement-making sofa by British-Nigerian artist and designer Mimi Shodeinde is part of a 10-piece collection exploring the line between motion and stillness. Featuring a solid base of tarnished aluminium and suede-like upholstery, the modular seating is accented by a Spanish nero marquina marble sidetable. Through its disciplined angles, this functional art piece mines postmodern and brutalist influences with bold results. POA. miminat.com

03.

Henry Holland Swirl tumblers.

British fashion designer Henry Holland makes his first foray into glassware with these kaleidoscopic mid-ball tumblers, which epitomise design-driven functionality with their swirling pattern inspired by the marbled nerikomi pottery of Japan and built-in ‘cookie-foot’ coaster for maximum stability. Handblown in the southeast of England, this six-piece collection of ice-clinking vessels sits nicely alongside the stripey ceramics range that Holland created with fellow designer Paul Smith. $827. henryhollandstudio.com

FrancoCrea Spikes mirror. This high-gloss wall piece by Italian-Australian designer and architect Franco Crea evokes a watery surface, scattering natural light in all directions while providing the visual intrigue of a surrealist artwork. Handcrafted in Italy, the wave-like frame incorporates sustainably sourced glass and copper in a way that adds dimension as well as a warming sheen. $7348. francocrea.com.au

05.

Forever Studio Flat Light. This resin table lamp from Rotterdam-based product designers Bienke Domenie and Sara Degenaar combines quality materials and a minimalist sensibility with playful pastels. The energy-efficient LED lightbox blends five different hues within its geometric silhouette, serving as a mood-boosting centrepiece for a cool-toned family room or home office. $3893. apoc-store.com

Pinpointing where we are in the cycle is nowhere near as straightforward as it was in years gone by. Here, NAB chief economist Alan Oster and JBWere chief investment officer Sally Auld posit some near-term predictions for Australia’s economic health, business prospects and investor priorities.

The ambient uncertainty that has pervaded economic discourse since we emerged from the grip of the pandemic has prompted even the most seasoned forecasters to question their reasoning. JBWere’s Sally Auld says: “Last year was humbling for economists because things turned out better than everyone expected despite the interest rate hikes, and Covid factors are taking longer to play out than predicted.” She says there is consolation for investors who have felt constrained by such ambiguity; “Even though the outlook might be difficult to pin down, the opportunity cost of not being full-steam-ahead on growth assets is actually pretty low at the moment, so you shouldn’t feel like you're missing out on a whole lot by structuring your portfolio defensively.”

On the other hand, this continued deferral of the “end of the cycle” has NAB’s Alan Oster concerned about how long the average Australian can continue their financial juggling act, with savings having dwindled and concerns about job security mounting according to behavioural surveys. He says: “We have at least another six months of tough conditions, with services inflation proving sticky and a while before the Reserve Bank starts cutting, with that likely to be at a modest rate of 25 points per quarter. The question is when exactly will the people whose mortgage payments grew by $2000 a month last year simply run out of money? That’s not far down the track if we don’t make serious progress on reaching the mid-range inflation target.” As of January, inflation is expected to get down near 2.5 per cent by late 2025.

Rather than turning to history to map the rest of the cycle, we find ourselves in largely uncharted territory. Oster continues: “The difference between now and 1989 is that unemployment remains really low, though it has risen slightly in recent months and is likely to continue creeping up without the job creation

to support school-leavers and immigrants.”

He suggests Australian employers need to be creating around 40,000 jobs per month to accommodate the increase in migrant arrivals, but sluggish economic growth makes 20,000 more realistic. If the unemployment rate for the population as a whole stays below 5 per cent, he remains optimistic.

With job security and post-pandemic revenge spending shoring up consumer activity until now, Australian businesses have been relatively insulated. Weak forward orders for retail goods and consumer services, however, indicate that confidence has taken a dive.

“Business confidence, which tends to be a more reliable sign of economic performance than consumer sentiment, has dipped to 2012 levels according to our SME surveys,” explains Oster, while adding that below-average GDP growth of 1.7 per cent is expected through 2024. Taking a step back to consider Australia’s position relative to similar economies, we find more encouragement. Oster agrees with Treasury forecasts that we could be back to 2.25 per cent economic growth by the end of 2025. “If we needed to, we could still fire up fiscal policy because our debt-to-GDP ratio is quite low¬, and not many countries can say the same,” he adds. Auld agrees that Australia’s foundations remain strong, even if the halcyon days might be over for some investors. “We have strong population growth and a medium-term fiscal situation nowhere near as dire as countries like the US and the UK. For the past 20 years we have enjoyed mostly one-way traffic in house prices and equity markets, but that’s not the world we’re in anymore.” She continues: “You’re going to have to be a bit more thoughtful in how you structure your portfolio and be more open to changing things up more frequently.”

Though high private equity valuations are offering limited upside, Auld says attractive options for downside protection should not be overlooked. “The silver lining is there are opportunities for investors to earn attractive running yields in fixed income, which is just a nice asset class for parking some funds,” she explains.

In terms of industry momentum, the decline in discretionary retail, CBD office and transport is contrasted by the strength of sectors such as value-added manufacturing and healthcare. The outperformance of the S&P 500’s big technology stocks last year is also expected to have significant flow-on effects in 2024. Auld explains: “Artificial intelligence is a structural thematic, in that NVIDIA has been the darling stock and now people are thinking more broadly about parts of the economy that are likely to benefit from this technology, such as healthcare or financial services, and looking at the companies that are building the data centres, for example."

Another key talking point in 2024 is the importance of diversification as a strategy for mitigating risk in an investment portfolio, with close to half the global population heading to the polls. “The noise around this year’s major elections everywhere from the US to India to Taiwan, and the European Union, is adding to the sense that this world is not quite as nice as the one that we’ve lived in for the past couple of decades,” Auld says. “You’re going to have to be a bit more thoughtful in how you structure your portfolio with a keen focus on both asset allocation and diversification.”

Though geopolitical risk is not going away anytime soon and Australia seems to have diverged from the road taken by similar nations, its reputation as a robust and innovative economy is holding firm.

For serial entrepreneur and problem-solver Geoff Harris, tethering social good to solid commercial principles and enabling others to unleash their full potential is all part of the playbook. – By

Tim BorehamEntrepreneur and philanthropist Geoff Harris says his approach to giving has evolved over time, but what has not changed is his core belief that good business principles and helping vulnerable sections of the community are intertwined.

“In the early days I thought ‘why would I give anything to the community, that’s up to the government via taxes’,” says Harris, who co-founded Flight Centre with Graham Turner and Bill James. “That was my 1980s view. But later I thought we needed to create a workforce where staff feel proud about the values of an organisation and help the community where our customers are. So it was apparent that doing something for the community was good for businesses, as well as for the community itself.”

Harris remains a 7.6 per cent shareholder in the ASX-listed travel group, which sold close to $22bn worth of trips last financial year. “Over time, we became more successful [at Flight Centre] and we had more free cash,” he says. “I took a step back after being in the management team for 20 years; I wanted to do some different things in my life and was donating directly to various causes through the 1990s.”

These days, those various causes have been supplanted by a more formal giving strategy, channelled through the Harris Family Foundation created in 2020. The foundation is very much a family affair, with son Brad overseeing day-to-day operations, daughters Alicia Bresolin and Caitlin Buerckner sitting on the board and Harris’ ex-wife Susan still involved.

“As a businessman, I believe in entrepreneurship and I believe we should do something for the community as well,” Geoff says. The foundation is set up as a public ancillary fund (PAF), by which the money remains in the structure but earnings from investments are dispersed in perpetuity.

“Hopefully we can top it up so that every year the corpus gets larger, the returns get larger and every year you can give away more and more,” he adds.

Over three decades, Geoff and Susan donated more than $35m via their own personal foundations. “The Harris Family Foundation is the next iteration of our giving

structure, […] a central foundation in which all of the family members are stakeholders,” Brad explains. Current priorities are at-risk youth, homelessness, health and medical research, disability support and environmental causes.

A modus operandi for the foundation is helping charities with their occupancy costs, which is usually the second-biggest expense behind wages.

Harris was a board member of the Reach Foundation, the youth support charity co-founded by the late AFL footballer Jim Stynes. After a fruitless six-month search for premises for the charity, Harris bit the bullet in 2002 and bought a run-down former knitting mill—now known as The Dream Factory—on Wellington Street in Collingwood for $2.5m. He negotiated with the state government to forgive land taxes and with the local council to exempt the building from rates and other charges. “We begged, borrowed or stole the materials to do it up, then rented it to Reach for 50 years at $5 a year,” he says. “Pre-Covid we were assisting 13,000 kids a year; that’s a building for them forever and a day to do their great work.”

Similarly, in 2013 he acquired nearby Cromwell Manor for $2.3m for STREAT, a not-for-profit social enterprise that teaches hospitality skills to homeless and at-risk youth. “I see social enterprises as a disruptor of the charitable industry because it gives you a sustainable economic model,” Harris says. STREAT, for example, has a café, roastery and catering operations to derive income. “STREAT was 82 per cent self-funded from its business activities in 2019 and aimed to get to 100 per cent by 2022, but Covid didn’t allow that,” he adds.

There are around 12,000 social enterprises in Australia, which together employ more than 30,000 people, according to the latest report by certifier Social Traders. By comparison, there are around 60,000 registered charities. Harris laments that Australia remains behind other countries in accepting and regulating social enterprises;

“When STREAT was set up and it derived profits, the government didn’t know how to handle it. They were a charity, yet they

were running a private business. [The state] just didn’t have the regulatory framework in place.”

The Harris brand of philanthropy is less about money than providing direct mentorship and business advice. “Usually the founders of charities are incredibly passionate and excellent people, but they don’t have the business structure and disciplines to ensure the organisation is running well,” he observes.

Helping vulnerable youth has a particular resonance for the 72-year-old.

“I had an issue when I was a teenager; I was bashed in the school yard over a six-month period,” he recalls. “As a 14-yearold that really affected me. Luckily, I had a strong father figure who helped me out. I really feel for kids who don’t have a father figure and lose their way.”

He cites one teenage bullying survivor he met through charity work; “He was this cheeky kid who had issues going in and out of the courts, and we just clicked. He ended up being a truck driver, which was his dream job, [proving] there’s a nugget of gold in there somewhere, you just have to get it out.”

Then there is the family’s $60m Gate 8 building development, a six-level philanthropic and entrepreneurial hub taking shape in East Melbourne—a drop punt away from the Melbourne Cricket Ground.

The Jolimont Street project, due for completion mid-year, is named in reference to the hallowed sporting ground’s seven entrances.

Designed by urban design firm Rothelowman, Gate 8 will devote about a third of its space to social enterprises and charities with the hope that colocation will enable these organisations to learn from one another. An entire floor will be donated to the administrative teams of not-for-profits such as STREAT’s training program and the Community Spirit Foundation (formerly the Cathy Freeman Foundation). The development marks the grandest manifestation of Harris’s real estate assistance model to date, with $550,000 of collective annual rent expected to be

foregone. “If charities don’t have to pay [rent] it gives them the equivalent of an annualised ongoing donation, and these funds can go straight towards their programs,” he says.

Gate 8 will also house dozens of startups and SMEs alongside Harris Capital and the Harris Family Office, plus a ground-floor café run by STREAT that will benefit from peak foot traffic during sporting events.

As former vice-president of the Hawthorn Football Club, Harris has spent many happy hours at the MCG (especially during the club’s streak of three consecutive premierships between 2013 and 2015). But Gate 8’s proximity to the ground is about more than sentiment: the venue is well served by public transport, which also makes it easy for disadvantaged clients to access the building and its services. The sports benefactor has also integrated a 130-person auditorium into the design in order to host youth workshops when the ground is not in use.

Beyond the historic home of Australian sport, the family’s biggest donation to date is a $10m pledge towards Hawthorn FC’s new training base in south-east Melbourne, which incorporates a community centre for women’s football.

Then there’s Straight Bat, the family’s recently created private equity (PE) fund. Unlike traditional PE firms that tend to take control, cut costs and then divest, Straight Bat advocates a genuine partnership with existing proprietors. “We buy a substantial percentage of the business, sit with the founders and aim to pay 10 per cent dividend to investors plus grow the capital,” Harris explains.

Brad Harris says the investments range from minority to majority positions and are intended to be held for the long term (the fund has an 80-year, open-ended structure). “We are not interested in flipping them every four or five years like a traditional PE company, we work with the founder and aim to grow the business in a sustainable and structured way.”

As such, the investment strategy might span several decades, with a view to succession planning for the next generation of Harrises. With $250m under management, the fund is defined by “relatively boring, steady-Eddie investments that can perform through all cycles,” Brad says. “We are not looking for rocketships or startups that might make or lose 200 per cent. As long as they continue to be successful and we are paying annual income dividends of over 10 per cent to investors, we don’t have to sell the business to recoup the capital.”

At the time of writing Straight Bat has invested in seven companies, including the law firm Wotton + Kearney. “Law firms tend to grow consistently without shooting the lights out, and rarely go to zero either,” Brad notes. “We also have a smoke alarm manufacturer [Red]. We like them because [the product is] a legally mandated requirement for every building in Australia so there are at least 400,000 purchased every year for new buildings.”

Geoff Harris adds that Australia’s 60,000 SMEs remain the backbone of the economy. “If we can invest in these SMEs and, through the collective Straight Bat business skillset, enable the proprietors to grow them to large businesses, we are doing a good thing as well,” he says. “It’s a noble investment category because it is the engine room of Australian productivity growth.” Harris suggests there are several transferable learnings when it comes to leadership in sports, social enterprise and traditional business. “You need a clear vision and great people in key positions,” he says. “The CEO needs no fewer than six of those ‘A-graders’ as direct reports, and must delegate and communicate well. Honesty, transparency and a humble mindset are important… as is having a bit of fun along the way.”

Art

– By Hayley Curnow

– By Hayley Curnow

Sarah Fletcher’s fascination with art is, no doubt, innate, having been surrounded by artists from early childhood. Her mother was an antique collector and her father a geologist, entrepreneur, art collector and former chair of Heide Museum, who was “obsessed with people who could create something of value out of nothing,” Fletcher says. One formative memory was when he commissioned then up-and-coming Melbourne artist Bruce Armstrong to craft a ‘silver swan’ maquette to symbolise a nickel mine her father had founded in Western Australia. “Dad kept saying that he couldn’t see the passion in the models Bruce was producing, until Bruce screwed up a coat hanger in frustration, and there it was, this swan,” she recalls, eyes sparkling.

This same attitude of questioning, challenging, and driving creative ingenuity and expression has shaped Fletcher’s attitude to arts practice today. “My influences are the creators, the builders,” she asserts. “It is breathtaking what artists invest of themselves; they shed flesh to add something beautiful and meaningful to the world, and it’s a privilege to be part of the process.”

After establishing a disruptive apartment gallery in St Kilda that showed “you can have your bacon and eggs beside a good piece of art—it doesn’t need to be precious”, and Franque, a distinctive emporium of luxury goods and art in Toorak, Fletcher felt compelled

to revisit her core message. “I wanted to focus more on the raw expression of what art is,” she says, “because it’s not a fashion accessory.”

Enter Fletcher Art, a gallery proposition and curatorial service that gives substance to Fletcher’s visceral comprehension of art and space, while feeding her passion for engaging directly with artists. Evolving her previous entrepreneurial endeavours, Fletcher Art’s antiquefurnished consultancy and gallery — inconspicuously housed above a Korean restaurant in South Yarra — is complemented by an intimate home salon in Toorak, open to collectors by appointment.

Upon entry, Fletcher’s home unfurls as a light-filled treasure trove of art, antiques, and collectables, its ‘un-done’ quality and continual

reinvention provoking a blend of private clients, artists, designers and architects to consider new spatial compositions. She buzzes between works by the likes of Richard Stringer, Peter D Cole, Lisa Roet and Holly Grace with fervent energy. “The dynamics are there to explore,” she says. “Love it or not, we are not here to please but to execute an everchanging experience of potential scenarios. It’s not radical stuff, but it’s challenging and a little gritty. It’s just enough for buyers to feel excited [and] a little uneasy.”

Representing 20 established and emerging artists, designers and craftspeople, Fletcher relishes the opportunity to speak compellingly on their behalf—an act requiring great trust. “Many artists underestimate the power of their ideas,” she suggests.

“I often get to be part of the dialogue, to offer suggestions or just listen, which is a rewarding and nourishing process,” she says, smiling. Regularly visiting artists in their studios, Fletcher gains an inherent understanding of their process and artistic narrative, which she shares with her buyers to enrich their appreciation of acquired works. This commitment has enabled Fletcher Art to cultivate a pulsing community of artists, craftspeople, and collectors. Fletcher frequently hosts artist lunches at her home, where the more established artists informally mentor fledgling ones by sharing ideas and advice, imploring them to ‘dust themselves off’ in trying times. Once a month, Fletcher invites like-minded collectors to a home gallery soiree to celebrate a new artist

01. Moon goddess ceramic dancers and wall piece by Sally Kent; painting by Bruno Leti; photographic work by Marnie Haddad, and ceramics on console by David Ray. 02. Sculpture by Peter D Cole. 03. Bee Replicas by Richard Stringer; Antique Murano sconce; bronze Lovelock coat stand by Barbera.

“I don’t follow trends. Trends have an expiry date, but good art and design simply shouldn’t.”

or theme, to converse, interpret and validate new works, bolstering the spirit of the art community.

Fletcher’s skill in facilitating connections between art, artists and collectors also underpins her approach to curation, which acknowledges art collecting as a highly personal and emotive act.

“My job is to understand how the client ticks, give choices and then step aside while they sit with it,” she explains. In the pursuit of harmony and balance, Fletcher assembles new and existing works through the lens of the collector’s identity, and harnesses negative space to allow the talent to breathe.

Her curatorial approach consistently eschews trends and recognises art’s inherent subjectivity.

“Whether it’s a dead bee sculpture on a building by Richard Stringer, an elaborate ceramic by David Ray or a glass work by Louis Grant, I can only back what moves me, and I don’t expect everyone to be moved in the same way,” she says. “Some artwork that is horrific to one may be [adored by] another. I cannot and should not try to convince anyone to love something. In fact, the best part of my job is when the right artwork finds the right client organically.”

While she rebuffs the concept of having a ‘good eye’, Fletcher says she does indulge her instinct “as a circuit breaker to pull ahead”. Her history of working in different roles and with challenging spaces has honed this instinctive approach, giving rise to what she describes as “dynamic, unexpected outcomes that are the opposite of contrived”. Feeling guides Fletcher’s incisive selection of artists for Fletcher Art and her careful curation of pieces for clients.

“I have a rule that I don’t handle any artworks I wouldn’t want to own myself,” she reveals.

While Fletcher Arts’ catalogue of works is covetable, diverse and everevolving, Fletcher is most enamoured by works expressing the elemental journey of raw materials, and our place in that journey as collectors and admirers. “Ceramics, glass, stone and bronze have helped form modern civilisation as we know it and will continue long after we are gone,” she says. “It is a luxury to be a part of their narrative for a moment in time.”

Some of Fletcher’s most cherished pieces in the gallery today echo this sentiment, including Lisa Roet’s striking bronze gibbon hand, a commentary on our relationship and connection to other primates; a glass

work by Adelaide-based artist Jessica Murtagh; and, perhaps most notably, a solid marble console by Melbourne furniture designer Daniel Barbera. The cut grooves of this work reflect ancient stonemasonry techniques, executed with a restraint that honours the marble’s beauty in its natural state. Given the resonance between Fletcher and Barbera’s artistic ethos, the duo is set to collaborate on a satellite presentation titled BCE (Before Current Era), for this year’s Melbourne Design Week.

Gazing around her home gallery—a place with continual movement—Fletcher’s eyes dart between sculptures by Peter D Cole, a recycled material work by Carlo Golin, and back to rest on Barbera’s console. “I’ve always loved the quote from French writer Paul Valéry: ‘The idea of the past assumes its fullest significance and value only in those who are filled with passion for the future’.” With an unwavering interest in what lies ahead, she indeed grasps the lessons of history with rigour and wonder, her artistic nous instinctively shaping future comprehensions of art, space and design.

fletcherarts.com

01. Italian chandelier from Graham Geddes; antique Italian tryptique mirror; brass forms by Kirby Bourke at Two Lines Studio, and Riot Cops by David Ray. 02. Painting by Deborah Walker; neon cross by Sanja Pahoki, and small bronze sculptures by Graham Fransella.

The architect behind the new-look Southern Ocean Lodge shares what it took to recreate the iconic clifftop resort from the ashes of 2020’s Black Summer bushfires. By Leanne

Consistently rated among the world’s best high-end resorts, the ‘rugged luxury’ Southern Ocean Lodge on Kangaroo Island off South Australia set new standards for hotel design, sustainability and experiential tourism when it first opened in 2008. Since then, the lodge has spawned its fair share of imitators according to Max Pritchard, the original architect invited back by Baillie Lodges founders James and Hayley Baillie to craft the vision for SOL 2.0.

Pritchard (a KI native) and his business partner Andrew Hunner oversaw the two-year $55m rebuild of the celebrity-friendly lodge, which was destroyed by fire in 2020. Officially reopened this past December, the secluded property sits atop a 40-metre cliff on the island’s southwestern edge, bordering national parkland with uninterrupted views of the vast and mysterious Southern Ocean.

Multiple logistical challenges threatened to derail the reopening, from post-Covid materials shortages to the obvious accessibility issues that come with a remote location. “When you consider all of those things together, it's just remarkable what we have achieved in two years,” Pritchard says, adding. “I have residential projects that take longer.”

While guests will be familiar with the lodge’s trademark interiors, Pritchard says one particular feature has been a talking point over the years. “When we first opened, some people [queried] ‘why are you doing a 1960s sunken lounge?’,” he recalls. “But it wasn’t long before we started to see the concept appearing in other developments around the world; details blatantly copied from Southern Ocean Lodge such as sunken lounges in all the suites.” He adds: “This time around, I thought—perhaps a bit arrogantly—that’s enough; we have to raise the bar again and do things a bit differently.”

The redesign incorporates 23 guest suites, each with coastline views, plus a new four-bedroom Ocean Pavilion set away from the main building for privacy-seeking families or those travelling with staff. Other additions include three spa treatment rooms, a gymnasium and sauna, plus hot and cold plunge pools.

Passive design principles have been employed to support natural ventilation and heating, while hybrid solar and battery energy sources allow the lodge to run off-grid. To counter future bushfire threat, the lodge’s rainwater harvesting system has been expanded, a bigger 20-metre buffer set around the buildings and 45,000 fire-retardant native plants used as a mainstay of the gardens.

Pritchard’s focus for the new design was delivering a more immersive experience of Kangaroo Island’s unique landscape. “I get quite nostalgic for that smell of the bush and the sound of the wind and the leaves… I like [exploring] how those elements can be transferred to a building through design,” he says.

“One of the biggest changes we made was to reorient the suites to look down the coast [not just directly out to sea]; it seems like a minor tweak but has made quite a difference to the feeling within those rooms,” Pritchard explains. “The beds are quite close to the windows, giving the feeling that you are hovering over the ocean while nestled in nature with the vegetation around,” he continues. “You're not just getting that straight sea view but a view of the whole coast, seeing more of the clifftops and surrounds. I think it provides guests with a better feel for the island and a greater sense of place.”

In terms of interior architecture, Pritchard describes the new design as “more sculptural” with curved walls creating a feeling of being immersed in an organic environment, as do Tasmanian blackwood bedheads and the stone fireplaces now found in every suite. Another material used throughout is local limestone, which was quarried on-site. “Nothing quite connects you to a place than stone sourced from where you stand,” he says.

Each of the suites is finished with South Australian art and wares, including handblown glass lighting by Ross Gardam, bespoke tableware by Malcolm Greenwood and custom furniture by the late Khai Liew. Elsewhere, a limestone wall by stonemason Scott Wilson adds to the feeling of connection to the surrounding landscape. The lodge’s restaurant, meanwhile, offers all-day dining and an open bar, with a spotlight on South Australian wine and regional produce.

For Pritchard, the project is a full-circle moment, both in rebuilding what was lost and deepening his appreciation of his homeland. “The Southern Ocean is so unique; you get to look out and there is nothing between you and Antarctica. To be able to design a place where others can appreciate this same view, this same experience, is quite special.”

A signed, first-edition 1929 copy of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own sits atop a pile of books on a leather-inlay desk. Behind it, expansive bookshelves are filled with more rare reading material; novels by the likes of Jane Austen and the collected works of Oscar Wilde, along with coffee-table books covering the gamut of art, design, fashion, architecture and photography. Bold names leap out from supine spines: Richard Avedon, Tom Ford, David Bowie, Yves Saint Laurent, Frida Kahlo. For Amber Symond, this room is a beloved corner of the harbourfront mansion in Sydney’s Point Piper that she has shared for a decade with Aussie Home Loans founder John Symond, from whom she formally separated in December.

A regular venue for charity events, the sprawling Wingadal Place home is famed for the art collection woven throughout. The library room’s appeal is exponentially enhanced by a number of paintings by iconic Australian artist Brett Whiteley, for instance. On one wall, a large work backed in cobalt blue featuring an unfurled

frangipani and a hummingbird; on the facing wall, a scene of bathers on the beach in Byron Bay. A smaller frangipani painting hangs to its right. Sitting on a teal velvet sofa beneath the cobalt painting, Symond says she feels authentically herself in this space.

“It’s just the energy of the room. It's a quiet, relatively dark space in an otherwise very bright house. It feels like a safe environment, where I am surrounded by books and music.”

The soundtrack in the background of our conversation happens to be laid-back— the Rolling Stones’ Miss You and a remix of Neil Young’s Harvest Moon for starters.

She says it’s probably a playlist from one of her two teenage children. But on another day, her own choices might include baroque or indie, including The Jesus and Mary Chain or The Cure. “I am attracted to the music of my youth, which is more punk and alternative, because it is particularly jolting… but I also love classical music. My tastes are quite diverse and forever evolving.”

Beyond the library hang modern works by Andy Warhol, Banksy, Jeffrey Smart, John Coburn, Lynn Chadwick and a particular

favourite, Columbian artist Fernando Botero, whose rounded figures feature on walls and in sculptures. “I find any kind of art mood-altering, but particularly music and literature,” says Symond, adding that art offers much of the inspiration behind her luxury fashion label, Common Hours. Launched in 2019, the brand is something of an anomaly in the Australian fashion industry. The price point—which ranges from $750 to $10,000, with many of its signature robes sitting around the $5000 mark—naturally narrows the field of consumers, but the brand is about more than catering to high-earning fashion lovers. The ideal customer is a collector of sorts: “someone who cares about the rare”. There is a distinct sense of intimacy to the garments, for both Symond and the wearer. “Hidden details are an important component,” she says. “At first glance a lot of our garments just look like gowns or opera coats designed to drape elegantly, but on the inside you will often find musings and motifs and messages that the wearer can identify with. It's like a tattoo almost,

01. Symond wears the Anonymous Source mesh halterneck dress from her label. 02. Puff Piece dress with fabric printed in Italy to feature 1971 newspaper clippings. Image: Jake Terry. 03. Fitting Polaroids.

that's just for yourself. It's tongue in cheek with a sense of irreverence but could also be something personal. It’s certainly personal for me; everything I make is very personal.”

Some pieces are reversible, allowing those internal musings to be put on show to the world. “I loved the idea—the almost silent or provocative protest—that you could have a riot inside that might be for yourself, but on the outside, it could look perfectly reserved and restrained and elegant. Or you could reverse it,” she says.

When we meet Symond wears the kimono-style Music and Dance robe from her first collection, featuring the jazz-era performer Josephine Baker of La Revue Nègre as painted by French artist Paul Colin in the 1920s. In keeping with the brand’s ethos of scarcity and craftsmanship, it is one of just 50 produced, the maximum number of editions for any Common Hours release. “On average, we make 20 to 30 units of each piece. I don't ever want to make more than 50 worldwide, which makes the proposition more special for our customers,” she says.

The Colin artwork was licensed as part of an elaborate process Common Hours undertakes to secure usage rights for the artworks or lyrics it incorporates into its designs. “It’s important to me because artistic skill and integrity should be respected,” Symond says of the lengths it takes to acquire these permissions from copyright holders. She cites a hooded cape made from a wool and cashmere jacquard that features Tamara de Lempicka’s Portrait of the Marquis d’Afflitto (1925), licensed via the artist’s estate. “I've had the opportunity to use two of [Lempicka’s] artworks that were very masculine, and was initially intrigued to see how menacing her protofeminist imagery might appear on a dress made of suiting fabric.”

A silk-cotton robe dress from the brand is covered with lyrics from The Cure’s Pictures of You , while another gown quotes Romeo and Juliet by Dire Straits. This style of box-sleeve kimono was the starting point for Common Hours. “They're a great canvas to imbue with all sorts of artwork, and the

design is versatile,” Symond explains. “You can wear it to an evening occasion, to a lunch, over swimwear, around the house; you're only limited by your mood.” She concedes the wrapround style can also feel like personal armour to shield yourself in, which is how she approaches all fashion: “It's an extension of how you're feeling at any given time.”

Later in the day Symond is swathed in the Infinity and Time gown, a black leather robe that looks equal parts tough, sexy and supremely comfortable. It is delicately embroidered with constellations and blossoms by the Chanakya embroidery house in Mumbai, the same artisans used by some of the world’s leading luxury houses including Schiaparelli, Valentino and Christian Dior, the latter having recently showcased Chanakya craft in a dedicated runway show. “To be an Australian brand collaborating with international artisan communities of such skill and savoir-faire is remarkable,” she notes.

Fabric sourcing and development, largely undertaken with the best mills in Europe and Japan, is also an involved process. Often the fabrics are traditional natural fibres such as silk and wool, but Symond also explores technical fabrics to create different effects. “It takes a lot of time to make these garments, sometimes 45 days just for the hand embroidery. They sometimes go through many, many hands, from dip-dyeing and milling to embroidery for example. And we do most of our making in Australia for hand-cutting and the placement of artwork prints to make sure they render perfectly across the seams.”

This is one of the reasons that Common Hours releases no more than two collections each year, working against the increasingly fast pace of the global fashion industry, where brands often release four to six collections a year, or more. “I’m very respectful of the industry, but [the brand] just seems to have organically developed, and we’re going to stick to the authentic mode of what we do.”

As she descends the home’s central staircase towards a French silver candelabra, Symond’s gold Headline trench dress billows out behind her. The light-as-air silk lamé fabric was printed in Italy with Australian newspaper clippings from from 1971—the year Symond was born. The liquid gold dress is from the AlleyCat collection, which has a direct lineage to another personal chapter in Symond’s life. “Each collection has a different theme, or a memory or mood, and this time I was reminiscing about my

childhood. My parents had a wine bar in North Sydney in the '70s. They'd pile us into this Kombi van in the evening, because we lived on the Northern Beaches, and we'd go back and forth.”

Bands, such as INXS-prequel the Farriss Brothers, would play inside the bar as its patrons spilled into the alleyway outside.

While they were meant to be sleeping, Symond and her sister often watched these goings-on, wide-eyed, from the windows of the van. “It was this come-as-you-are nocturnal scene where all these fantastic characters would converge,” she reminisces.

“The sort of gloss of these women, their [thick] mascara, the way they didn’t care if a shoestring strap slipped down one shoulder, the sense of freedom, of defiance... I was completely fascinated.”

That same ‘gloss’ theme plays out in the AlleyCat collection with wet-look coated jersey in dresses that skim the body, and the stretch PVC of a ruched red dress that zips up and down the back, while stretch lace plays peekaboo in bodystockings and halterneck dresses. A sketch of an alley cat by collaborating artist Judd Shoppee, stitched by Chanakya embroiderers, runs down the leg of a cream silk slip dress, while lyrics from The Motels’ Total Control are scrawled in graffiti-style text along the arms and skirt of a blue mesh sheath.

This mix of rock ’n’ roll with fluid elegance is part of the appeal of Common Hours. When Symond pairs chunky black boots with a dress of delicate mesh featuring metallic specks (one of only five

such textile pieces sourced from the Hurel heritage mill in Paris), then drapes herself over a Clive Murray White sculpture for the photographer’s lens, it all seems to strangely make sense.

The brand was stocked by Matches its first three seasons and is now available at Lane Crawford in Hong Kong. But the discerning customer is more likely to meet the brand—and Symond—at a private trunk show in one of two showrooms in Sydney or London. “It’s that very private, one-on-one offering,” Symond explains. “Luxury is being able to take the time to talk through a library of possibilities and themes, and it's a delight for me to see how different people wear their garments or what they're drawn to.”

Seeing people enjoy the finished garments is a thrill for Symond. “What starts as the germ of an idea might take over a year to become a garment that can be worn out in the world,” she says. “And it is quite remarkable to create that moment and unearth further inspiration along the way.”

She will not divulge details of the next collection (anticipated in June), except to say that it is “quintessentially Australian,” adding that it will be “great fun to bring it home.” No matter where she finds her inspiration, or in what art form, Symond is approaching the future of Common Hours with an expansive mind: “I want to take more risks and stretch creatively. To elevate a new idea and push myself further in each collaborative project is really exciting.”

WHILE MANY OF US LIKE TO THINK WE CAN PREDICT WHAT LIES OVER THE HORIZON, FEW HAVE THE BOLDNESS OR CONVICTION TO BRING SUCH A VISION TO FRUITION. FOR MELBOURNE-BORN AUTONOMOUS MOBILITY ENTREPRENEUR TIM KENTLEY KLAY, RECONFIGURING THE WAY THE FUTURE LOOKS IS ALL IN A DAY’S WORK.

Having founded an animation studio before computer animation was considered a profession, it perhaps should have come as no great shock when Tim Kentley Klay announced to his colleagues that he planned to develop one of the world’s first robotaxis in the early 2010s. “This is before self-driving startups existed besides the X division within Google, and everyone in the studio thought I was crazy going up against automakers with this robotic car concept that had no steering wheel,” he tells The Luxury Report by phone from his Bay Area office in California. “But when I first saw a Google-modified Lexus with autonomous steering, I had the realisation that this was about much more than lane-keeping on a freeway; this would shift us from the age of the automobile to the age of robotics.”

Not only had he become obsessed with the concept of vehicular autonomation at an early point in the technology curve, but the funding sources he would need to mine to turn drawings into design prototypes were far from established. “This was before the notion of venture capital really existed in Australia and it was actually a contact in Silicon Valley who suggested I speak to Niki Scevak, who was just starting Blackbird VC and became our first cheque writer,” he recalls. “To be saying ‘Hey I’m Tim from Australia and I want to start a self-driving company’ was kind of unusual in 2012, but step-changes generally come from people outside of a given industry because we don’t see all the constraints that hold others back.”

The largely Australian-funded robotaxi firm, Zoox, would go on to be incorporated in the US and achieve a valuation of US$3.2bn within four years, before ultimately being acquired by Amazon in 2020. Scevak’s Blackbird returned “for another round of punishment” when Kentley Klay fundraised for his latest venture, AI robotics lab Hypr.

Relocating to Silicon Valley in his late 30s was a no-brainer for the commercial artist turned technical entrepreneur, despite having almost zero local connections. As it so happened, many of Kentley Klay’s early employees chose to follow him Stateside to challenge the likes of Alphabet’s Waymo and General Motors’ Cruise. He says: “The move was motivated by the need for oxygen; if you

have a big idea, you need to plant that tree where there's maximum oxygen to get maximum growth. I saw very clearly what was about to happen and that the technology was going to level the playing field for a moment, whereby an entrant who understood [how to make the] product experience and service better could get a foothold in the marketplace.” In those days, his advocacy for the vehicle-as-a-service business model was decidedly leftfield.

The archetypal Australian bluntness that helped Kentley Klay make a splash in those early years, however, may have contributed to his shock ousting from Zoox in 2018. He implies that the event continues to have ripple effects but ultimately served to strengthen his mental toughness and prioritisation skills. “When you're on top of the mountain and get pushed off by your own team, you don't just fall to the bottom of the mountain, you fall to the bottom of the chasm at the bottom of the mountain—and it's real dark down there,” he says. “But when you get out of that chasm… you're vastly stronger in non-obvious ways, [you can clearly see] where your intuitions were on point, and you don’t sweat [the small stuff].” The bidirectional four-seater without manual controls that he dreamed up back in his Melbourne studio entered its real-world testing phase on Californian streets last year.

Kentley Klay is bullish that car transport requires more than incremental change to meet the needs of tomorrow’s urbanites. With Hypr (which will launch publicly later this year), he has set a wider remit to create a machine learning model and robotic infrastructure compatible with all manner of vehicles. He explains: “Most robotic systems before 2020 were hand-engineered and computationally intense, requiring a lot of sensory hardware as well as power to run, all of which is hard to scale. The end-to-end Hypr [solution uses] the lowest-cost hardware, learns on the smallest training dataset, runs on the smallest amount of power, and requires the least amount of software engineers.”

He says the Hypr algorithm (four years in the making) and robot (“unlike anything you’ve seen in a movie”) can safely control a driverless car using as little as 20 watts of power and three days’ worth of efficiently extracted training data. Kentley Klay insists those who question the safety of driverless technology in principle do not appreciate its scope and points out that fatalities from traffic accidents are rising in the US despite despite continual improvement of automobile safety features. “As car technology is getting better, the human driver is tuning out more and more, and the only real way to solve that is for the AI to perform like a guardian angel that intervenes if you're about to do something dumb,” he suggests. This middle ground, where an AI co-pilot is considered the norm, is only a few years away, according to the future-ready business leader. He adds: “People underestimate how agile and robust these systems will be, [I have no doubt] we will see transport go electric and autonomous in all mediums.”

The size of Hypr in stealth mode certainly belies the scale of its ambition and multiplicity of its outputs across product design, robotics and artificial intelligence architecture. Kentley Klay jokes: “I tell investors they get 120 people for the price of 12 because everyone who works here is a 10X-er.” As to his ever-evolving role, chief navigator might be the best descriptor. “When thinking about which direction to head you’re putting your arm out into a dense fog, one where you can't even see your elbow, let alone your wrist. The power of the founder comes from where you point your finger, and creativity is reaching into that fog and pulling the future into reality.”

hypr.ai

Tim Kentley-Klay photographed by Maria del RioPhotography TASHA TYLEE

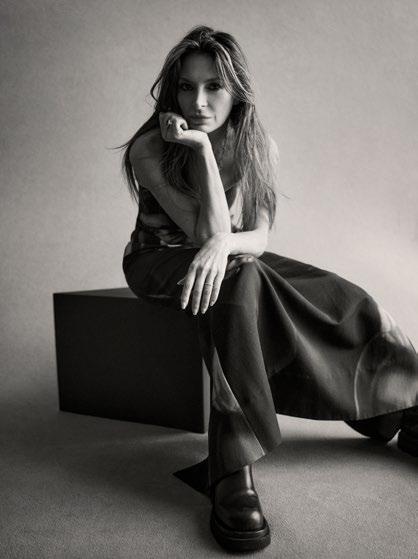

How Morris Family Foundation director Hayley Morris is harnessing her family’s fortune to cultivate meaningful impact — from boardroom to dining room, farm to table.

When it comes to professional commitments, Hayley Morris wears considerably more hats than most. From philanthropist and not-for-profit founder to environmental advisor, impact investor and executive director of her family office, Morris is as accomplished as she is scheduled.

A mother of three who splits her time between her beachfront St Kilda West home and the family’s 444-hectare Cape Schanck estate, 42-year-old Morris projects an admirably poised presence for someone who wrestles social, environmental and commercial challenges for multiple organisations on a daily basis. Her composure seems to be a mark of both regular meditation practice and a deeply rooted sense of purpose, as well as an inherited family philosophy that centres gratitude and altruism.

“Growing up, I was in awe of my dad and his achievements. He was entirely self-made. He had humble beginnings, worked hard and became extremely successful,” Morris explains. “I grew up very aware of the privilege and opportunities that [his success] gave me, but I think I also internalised a belief that any success of my own needed to be earned autonomously.”

Her father Chris Morris retains a stake in Computershare, the $14.8bn ASX-listed share registry service he founded in the ’70s, while also overseeing an expansive hospitality and tourism portfolio that includes the newly opened $20,000-per-night Pelorus private island in Queensland. Hayley has worked alongside him since her teens, first at Computershare and then joining the Morris Group of businesses where she now serves as director. She also heads up the Morris Family Foundation, which donates $2.5-3m annually to projects both at home in Australia and in developing nations.

Chris Morris, whose own parents opened their doors to a young refugee child in his youth, tells The Luxury Report: “Philanthropy and giving back were a strong part of my family’s culture growing up and this has stayed with me throughout my working life.” In 2005, he set up an employee giving program whereby Computershare matched payroll donations to local and global projects tackling poverty and climate issues, with some $11m donated since then. He continues: “When I retired as CEO and went to set up our family office in 2008, it was a natural step to establish the Morris Family Foundation as a part of this.”

Hayley Morris says her relentlessness, sense of possibility and appreciation of generosity were instilled in those early years as a Computershare employee, though the desire to forge her own path and a growing interest in environmentalism prompted her to step away from the business in her mid-20s.

After undertaking post-graduate studies in sustainability, she founded Sustainable Table, a not-for-profit connecting regenerative projects with philanthropic funds and impact investors. “I definitely inherited my dad’s work ethic and entrepreneurialism, so I used that to forge my own path doing what I was passionate about,” Morris says. She also co-founded Impact Sustainability, a business that provides companies with technology solutions that enable them to more easily monitor and take action to reduce their carbon emissions. She is still actively involved in both organisations.

After several years following the call to environmentalism, Morris reached a personal and professional juncture that caused her to reconsider how and where she could best use her skills to enact systemic change. “In 2014, my mum passed away and I had some time out from Sustainable Table and Impact Sustainability,” she shares. After this period of reflection, she found herself excited by the prospect of working on the expanding portfolio of businesses that would become Morris Group. “I got involved at a board level for most of the businesses and in the operations of some of the tourism businesses,” she continues. “And I had been involved in the foundation’s not-for-profit work through Sustainable Table, so it made logical sense for me to get [more heavily] involved there.”

Today, the Morris Family Foundation helps to deliver grassroots environmental and social justice projects in collaboration with First Nations communities and established charities in the areas of regenerative agriculture, climate action, ocean conservation and international

development. Informed by her sustainability expertise, the mission of the foundation is to the tackle the causes rather than the symptoms of societal and environmental problems.

“When I took a more active focus in the foundation, we started to be more strategic and look at ways we could support projects that had a geographic or issue-based alignment to Morris Group businesses,” she explains. “Mostly, I was driving the people and planet initiatives, and ensuring this was a focus for our CEOs. Through this, I got more heavily involved in the philanthropic community and then the impact investment community, to start aligning the foundation’s investments with environmental causes.”

The Morris Group stable now spans hospitality, tourism, technology and aviation. It includes pubs such as the Portsea Hotel, South Melbourne’s O’Connell’s Hotel and Brighton’s Half Moon, as well as craft breweries. There is also a charter fleet of helicopters and superyachts, luxury lodges and private islands on the Great Barrier Reef. Finding a way to merge the commercial success of these ventures with the increasingly urgent needs of the environment is central to Hayley’s professional ethos. Her work has long been anchored by her understanding of the interconnectedness of life, business and nature, and she’s been ahead of the curve in identifying the opportunities that are now emerging within that paradigm — in ways that many business leaders are only just catching on to.

This approach has meant innovating to find new ways to collaborate, economise and amplify impact through shared projects and common goals across the portfolio. “Dad always said ‘focus on what you are passionate about, and success — whatever that looks like to you — will follow’,” she says. “I have always been driven by a strong passion towards my interests in life, which are now very focused on environment and regeneration. I think this drive was passed down via both nature and nurture.”

Her next major project—set to launch this spring—harnesses much of this passion and is perhaps the greatest showcase of her trademark approach: a regenerative farming collective and 40-seat farm-to-table dining experience nestled within the orchards of the family’s historic property on the Mornington Peninsula, Barragunda Estate.

Designed by Melbourne architect David Dubois, the project will see an existing agricultural shed transformed into a 120sqm glazed pavilion dining room overlooking the market garden. Featuring recycled timber joinery and furniture, an open fireplace, and warm terracotta tones, the venue will incorporate a wine bar and store, plus an enclosed courtyard garden with fire pit and grill.

Aimed at “connecting people to the food system”, Barragunda Dining will unite Morris’ interest in food, farming and environmental restoration—while taking diners on a journey through provenance and

the seasons. This dedication to fresh produce feels like a full-circle moment, echoing her father’s formative experiences working on orchards in Templestowe as a child and later selling tomatoes at Melbourne’s wholesale produce markets.

Morris says: “One of the big challenges with the modern food system is the massive disconnect between the population, our farming communities and how our food is grown. Our vision for Barragunda Dining is to connect people to the way we are approaching farming through a regenerative lens and the best way to do that, always, is through simply enjoying a meal in a beautiful environment.”

She adds that the stories behind the produce, the influence of the location’s rugged natural beauty, and a strong sense of place will all play a vital part in the dining experience. “We’ve really seen from our [Morris Group] tourism businesses that when people step outside of their normal routine, they're so much more open,” she says. “In an environment where you are relaxed and connected to what you’re eating and drinking, everything just seems to taste better, and we tend to give much more value to it.”

Chef Simone Watts, who worked alongside chefs including Greg Malouf and Adam D’Sylva before heading up the kitchen at the Morris family’s Daintree Ecolodge in Far North Queensland,

will be at the helm of the new restaurant. She will split her time between the farm and kitchen, deepening her connection to the produce grown and reared on-site by the collective of small-scale local producers who lease plots on the property.

The farm currently produces beef, lamb, honey and a range of seasonal vegetables and orchard fruits, and Watts plans to introduce eggs and pork this year. “It certainly won’t be the small garnish kitchen garden that is often the case for restaurants, this one will be very productive,” Watts explains. She adds: “My style of food is very vegetable-forward; I like big, vibrant, generous dishes that make people feel good.” Indeed, the feel-good factor, which Watts believes is lacking in many dining experiences, is set to be a key ingredient at Barragunda Dining. “I don’t think there’s enough discussion in high-end restaurants about the nutrient density of food, and [of the possibility] for diners to leave feeling fulfilled—both emotionally and physically—which is what we want to create here.”

Watts says that ahead of the restaurant opening later this year, the collective is already selling wholesale produce to local grocers and supplying limited quantities to venues within the Morris Group, providing a diversified market for the growers, who operate independently. “I think chefs underestimate what it takes to plan a menu in advance, and to understand quantities and

succession sowing,” she explains. “The great thing about the way it’s being modelled here is that we [Watts and individual farmers in the collective] work together first, and any excess that is produced outside of our needs can be sold to wholesale clients or in our vegetable boxes, which we sell online.”

While the philosophical side of dining might be eschewed as high-minded by some, Morris believes today’s restaurant-goers are more open to learning about food production and the inherent interconnectedness of humans, nature and what we eat. She says: “We want to bring all those stories into the experience so that people walk away feeling nourished and that they've had a lovely time [while connecting] with the environment and with how the food has been grown.” She adds that while she’s “not trying to solve the problems of the food system with one restaurant”, the hope is that visitors can go home with at least a marginally deeper appreciation of what is on their plate.

When probed on what she might be doing if she had not returned to the family business, Morris is unequivocal; “I don't think there would have been any other path for me, I was so strongly pulled to this work that if I was doing something else, I'm pretty sure the universe would have woken me up in some other way and pushed me in this direction.”

01. The farm supplies an abundance of nutrient-dense organic produce.

02. The view across Bass Strait from Barragunda Estate.

01. The farm supplies an abundance of nutrient-dense organic produce.

02. The view across Bass Strait from Barragunda Estate.

Using hand-selected European straws and antique trimmings, Tamasine Dale is bringing high fashion quality and confidence to everyday headwear. Here, the Melbourne milliner invites us into her studio to see what goes into making the most intriguing of accessories.

“It’s a classic scene that probably hasn’t changed much since the 1900s, when women used to all work around a table and sew,” says milliner Tamasine Dale of her workspace. “[Much like then] we all sit around a very big table and work on hats and talk and sew.” Working from the lightfilled studio in her South Yarra home, Dale and her occasional workforce of three other hatmakers are among a cohort of craftspeople resisting the increasing pace of fashion. “It’s meditative, it’s one of those slow processes, like slow food,” Dale says of the art of millinery.

Flanking her studio is a meticulously organised storeroom filled with millinery materials and

other supplies that Dale has been amassing for decades, many from annual trips to the UK, France and Italy. Some of the wooden hat blocks she uses are a century old, with her urge to collect them dating back to the early days of her career in the 1980s.

Some found her; “When I first started out and had articles written about me, I remember this couple called me and said ‘we used to have a hat factory in the ’20s and have all these blocks we don’t know what to do with — would you like them?’ They were so thrilled that someone young was doing millinery and keeping it alive.”

Working largely in straw, Dale is focused on creating a small but concise collection of summer hats.

She recently returned to her business after 20 years spent raising children, studying and working behind the scenes in fashion, including creating hats to order for Paris-based designer Martin Grant and Australia’s Scanlan Theodore (whose founder Gary Theodore is her ex-husband). Each hat begins with a ‘hood’, a simple form made from woven straw sourced in Europe. “The straws that I choose are very fine, like the finest linens or silks. You don’t see them very much anymore, for a few reasons,” she says. “They’re expensive, hard to find, and you have to know what you’re doing with them.”

Similar to the process of designers draping fabric on a mannequin,

Dale’s process begins with the materials and her hands, rather than with a sketch. “It’s exactly the same [as the mannequin approach]. Straws don’t necessarily look good on every block and some straws work better on different blocks,” she explains.

The blocking method involves steaming and hand-moulding the straw hoods on to the wooden blocks. “You’re governed by the hat blocks that you have,” Dale continues. “Over the years I’ve had hat blocks made to shapes that I wanted, so now I have a library of shapes that I can call on.”

Once shaped, the straw must rest on the block at least overnight to set. “The longer it sits on the block the better shape it will take,” she says. “It has to dry and shrink to the block.” She continues: “The next day you take it off and start putting the pieces together. A lot of the brims in this collection are hand-rolled. If you think about the edge of a scarf that’s rolled and hand-stitched, it’s a similar process but we’re working with straw. It’s very fine and you have to know how to do it, but it gives you this beautiful, soft edge. Underneath that rolled edge is a wire that’s holding it into shape — that’s like putting its skeleton in place.”

An adjustable headband may go inside, perhaps some lining, depending on how comfortable the straw is. “I try to only work with comfortable, non-scratchy straws, but occasionally if it’s a garden hat I’ll use something else.”

Trimmings are the final flourish: “Often the hat calls for what it wants,” she says. “I’ve some beautiful raffia handmade flowers I bought in Florence, so they’re going on some garden party hats, not your classic everyday hat.” Grosgrain ribbons are a Dale signature. “I have a beautiful collection of vintage trims as well. I’ve always used them but am digging deeper into my stores and using them a lot more [lately].”

While some of Dale’s early hats now sit in the collections of institutions including the National Gallery of Victoria and Sydney’s Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, she is thrilled to be back on the shelves of Melbourne fashion and accessories boutique Christine, alongside global peers such as Philip Treacy and Maison Michel Paris. Dale says these hats are not the sort of styles destined for Flemington or Randwick, and while she previously tried to make her business work all year round, creating beautiful felt and velvet hats in winter, there is simply too small a market for winter hats in Australia. The resurgence of interest in summer hats, largely owing to growing awareness of the need for sun protection, has made space for her recrystallised creative mission: “To make beautiful hats that I want to wear every day.”

Tamasine Dale’s latest collection is available at Collins Street boutique Christine. tamasinedale.com

– By Freya Herring

– By Freya Herring

For rapidly growing furniture maker Jardan, a longstanding commitment to responsible manufacturing—exemplified at its new Melbourne headquarters—materialises in a distinctly Australian aesthetic.

In the realm of design, to be considered a contributor to the Australian aesthetic is no mean feat. For Jardan—the family-run furniture company celebrated for its homegrown character—such an achievement is centred as much in ethos and approach as on the look and feel of its products. Visually, there is a lightness and brightness to the materiality and form of Jardan furniture that suits the Australian air. You might say that each Jardan piece embodies the kind of national archetype we all wish to be—chilled-out yet aspirational, eco-conscious and intelligent, beautiful to look at and beautiful underneath.

The furniture is showcased in retail spaces that feel at once like walking into the pages of a magazine and into your neighbour’s home; you feel like you could sit down with a cuppa and read the paper before realising you are, in fact, in a shop. But perhaps what makes Jardan feel truly Australian is that it has always been designed and manufactured here, with great devotion to the landscape and local lifestyle.

“Part of [our inspiration] is the Australian attitude to life, which is unassuming, approachable, relaxed and playful,” suggests Jardan co-managing director Nick Garnham. “We don’t have the buildings they have in Europe. Instead, there is a lot of great contemporary architecture in Australia—really modern spaces in our rugged landscape.” Creative director Renee Garnham, Nick’s wife, has observed a difference in colours and textures too. “I do notice that what sells in Europe are those darker, richer colours,” she says. “People tend to go for a light tone over here; it’s a very different colour palette, more relaxed.”

The Jardan aesthetic is coveted by everyone from Sydney beachgoers to Silicon Valley billionaires. And while Jardan collections run the gamut of furniture and homewares, from chairs and tables through to ceramics and bed linen, the brand is perhaps best known

for its sofas—sizeable, smart and shapely modulars in a range of textured fibres and nature-inspired colours. Contemporary furniture often looks exciting but is rarely very comfortable. There is something inherently inviting and restful about the Jardan look, from the curvaceous waves of the Valley sofa and the nebulous form of the Ziggy ottoman to the sloping cushions of the Wilfred armchair, which envelop its timber arms as if embracing the chair’s hard form with a hug. The Nook sofa’s loose cushioning—and even its name—radiates laidback vibrations, while the Sunny bed, with its natural, stonewashed linen upholstery, gives off an easy coastal elegance. These visual qualities are underpinned by the brand’s origin story, which has family and locality at its heart. Jardan began under different ownership in 1987 as a traditional upholstery business based in Hawthorn. In 1997, while Nick was working in its eightperson team, an opportunity arose to buy it. Together with his brother Michael and father Barry, he purchased the business with a view to transforming it into a design furniture wholesaler. The Garnhams started off small, but it wasn’t long before Nick realised he had a flair for design. Later, Renee left her job in the fashion industry to join the team, and the business began to expand.

“I came in about 16 years ago,” Renee recalls. “Nick and his brother were producing these beautiful couches, and designers were coming in and choosing their fabrics and loving what they were making.

Then we purchased the timber factory [to begin] making timber pieces and I started picking different fabrics, working on the colours and bringing [the brand] to life a bit more.”

As Jardan gained popularity, Renee recognised a need to adapt. “When I was just starting out, we had a small room in the factory and I noticed a lot of designers would come in with their clients and be like ‘I can’t visualise the sofa in the space,’” she explains.

“I wanted to create that space where people were inspired. I really felt that we should go retail instead of wholesale. We launched the retail stores in 2014 and took it from there.” Jardan’s flagship opened on Melbourne’s Church Street that year, with Sydney opening a few years later, followed by Brisbane and Perth. A Byron Bay store is due to open next.

Nick says: “We had [a vision to] do a store like no other, so our first store felt more like a home. It had a beautiful kitchen, it had a fireplace, it was very welcoming. It wasn’t just a generic furniture store. It had art, sculpture and colour, with local stone and timbers. It was unique in the furniture space at that time [in Australia]—we reimagined what a furniture store would look and feel like for us. We wanted it to be approachable, and really tactile; to have a lot of integrity and have beautiful artisanal work from around the world, and then all of our lovely textures.

[We wanted to] create a unique Australian aesthetic around that story.”

Today, every store looks different, reflective of the community it slots into.

“With every fitout we really go to the nth degree with the architecture and local narrative, being sympathetic to that region or that building with a nice design arc around how we live in and fit into that community,” he adds. “We like to be a part of the communities where we open our stores; we get to know the people who live there.”

Jardan’s local manufacturing also cuts against the grain in an industry that largely produces offshore to maximise profits. In 2023, Jardan opened a new 16,000sqm factory and headquarters in Melbourne’s Scoresby, combining its upholsterers, timber factories and offices. From here the team can design, make, and photograph new products all in one place, enabling enhanced collaboration and efficiency. “In a couple of weeks, we can go from a concept to a realised prototype, and that’s where the real buzz comes from in this new space,” Nick enthuses.

The dedicated factory is a major milestone for the company and facilitates the continued deepening of Jardan’s commitment to responsible manufacturing. “We are carbon neutral [as certified by] Climate Active, we recycle, we upcycle. We really want to get towards net zero, and with this new factory, we’re getting really close,” Nick says. “For example, we used to send a lot of offcut timber to landfill, and now we’re shredding the timbers and capturing the sawdust offcuts to produce solid hardwood timber briquettes, which then can be sold for

people to use to warm their homes instead of virgin timbers.” Meanwhile, the fabric scraps that come with manufacturing Jardan sofas are now repurposed, and a stewardship initiative ensures products can be recycled or upcycled at the end of their lifecycles.

This might be one of the company’s biggest differentiators: its environmental intentions are backed up by action. As keen surfers who spend much of their free time in nature, Nick says it felt crucial for him and his brother to embark on the sustainability journey. “We didn’t want to be involved in a business that was just going to do low quality furniture that ends up in landfill; that was really the antithesis of what we wanted. We wanted to create something we could be really proud of.” Now, with more than 200 employees, the capacity to double production and a fiercely loyal following among architects and interior stylists, it seems this Australian story is only just beginning.

jardan.com.au

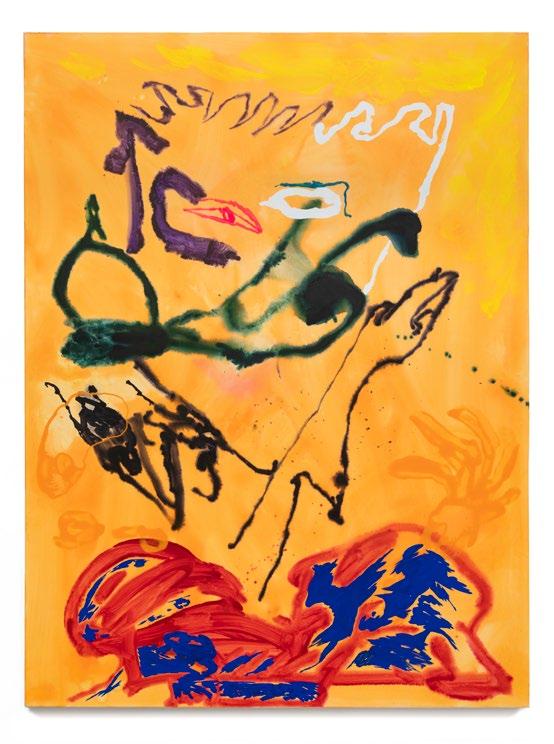

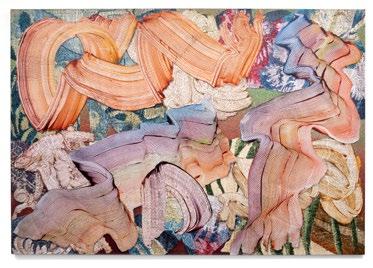

A guide to this year’s Melbourne Art Fair for emerging collectors, blue-chip art buyers and culture obsessives alike.by GABRIELLA COSLOVICH

Art fairs are an essential part of the global arts economy — think of the pulling power of Frieze, Art Basel and The Armory Show. With the majority held in Europe and North America, barely dented by the world’s recent economic woes, art fairs are now as much glittering social events as shopping sprees. While Australia’s largest art fair, Sydney Contemporary, has typically revelled in bigger crowds and sales, Melbourne is ramping up efforts to reposition its annual fair as a not-to-be-missed event.

As part of that quest, Melbourne Art Fair (MAF) chief executive Maree Di Pasquale has encouraged this year’s participating galleries to focus on a single artist rather than group shows. “With 300-plus global art fairs annually, it's important that we create a point of difference,” Di Pasquale says. “As a show that is now 35 years old, we felt that our strength was in its origins, in the fair’s relentless support of living artists… and we feel this is best achieved through solo presentations and a highly curated offering that is characteristic of an event that takes place in — in my view — Australia’s cultural capital.”