8 minute read

CHAPTER TWO CUNARD: THE EARLY YEARS

CHAPTER 2 CUNARD LINE: THE EARLY YEARS

Cunard Line owes its origin to the lucrative mail contract offered to tender by the British Government through the Admiralty in 1838. Samuel Cunard was born in Nova Scotia, Canada, on 21 November 1787. He and two brothers were ship owners with a sizeable fleet of sailing ships, but these were not suitable for the mail contract as they relied on the vagaries of the wind and were unable to keep to a reasonable schedule on the North Atlantic. Steamships offered a solution, but these were a relatively new concept. Under the direction of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the Great Western Railway, which ran from London Paddington to Bristol Temple Meads, formed the Great Western Steamship Company to extend their service from Bristol to New York.

Their first ship was the wooden paddle steamer Great Western, which, at 1,320gt, was the largest steamship in the world when she was commissioned

ABOVE Side elevation and deck plan of Britannia of 1840. BELOW The wooden-hulled paddle steamer Britannia inaugurated Cunard’s services in 1840.

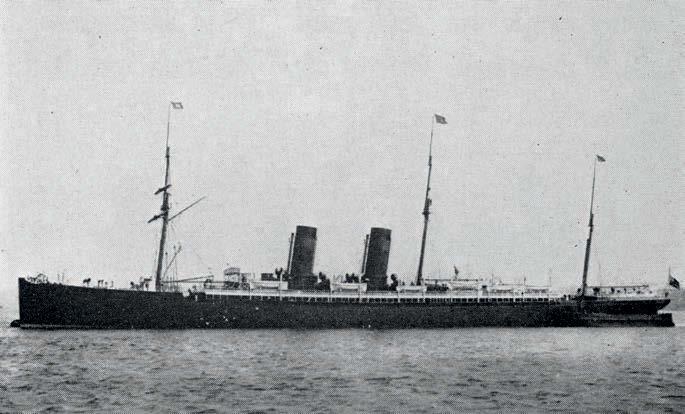

ABOVE Scythia of 1875 had a smoking room and an electric call bell system for her 300 First class passengers. She also carried over 1,000 passengers in steerage. RIGHT The 1884-built Etruria. She and sistership Umbria were the last Cunard liners which carried sails. Etruria had many distinguishing features including two enormous funnels. ABOVE Etruria with her auxiliary sails rigged. Along with Umbria, these ships were the last Cunard express liners with sails.

in 1838. Sailing at nine knots, she consumed 33 tons of coal per day and took about 15 days to make the Atlantic crossing. She was a well-appointed sturdy ship, designed specifically to ride the treacherous seas of the North Atlantic. Lavish accommodation was provided for 128 passengers and 20 servants, with a crew numbering 60.

Great Western was eminently successful, but the service she offered suffered from being based on a single ship. A much larger, even more luxurious iron-hulled screw-propelled steamship followed in 1845, Great Britain, but her transatlantic career was cut short after she ran aground in 1846. She was subsequently employed elsewhere by other owners.

Although Great Western Steamship submitted a tender for the Admiralty mail contract, it was awarded to the Samuel Cunard who proposed building three 800gt steamships to maintain a weekly service. The size of the ships

BELOW Persia of 1856 achieved a recordbreaking 13.11-knot speed, but this came at a cost: coal consumption of 145 tons per day made her uneconomic to operate. was then increased 960 tons, and again to 1,200 tons, while a fourth ship was added to provide the requisite service demanded by the mail contract, and also enable calls at Halifax as well as Boston to be made.

These ships were all wooden-hulled paddle steamers with a service speed of 8.5 knots. Passenger accommodation consisted of a dining saloon and cabins for 115, all to a standard considerably inferior to Brunel’s Great Western, as the four ships, Britannia, Acadia,

Caledonia and Columbia, were primarily mail and cargo carriers, with passengers as a secondary concern.

The enterprise thrived as it provided a dependable, regular, scheduled service which was initially unmatched by any competition. Further larger and faster ships were added by Cunard from 1843, and regularly thereafter, with more emphasis being given to the passenger accommodation.

However, Cunard was very conservative in his approach and it was not until 1855 and the introduction of the paddle steamer Persia (3,300gt) that wood was finally superseded by iron construction, although the use of paddle wheels for propulsion persisted until 1862 and the introduction of China (2,540gt), which employed a single screw propeller. Iron gave way to steel construction with Servia (1881/7,392gt) and with her speed increased to 16.7 knots.

Umbria and Etruria (8,127gt) of 1884 were the last Cunard express

ABOVE Umbria and her sistership Etruria were the last single screw ships built for Cunard’s express transatlantic service.

liners with a single propeller, and they each achieved a trials speed of about 19.5 knots. They were also the last express liners with an auxiliary sail rig, which was deemed essential if the single shaft broke, a constant danger with the quality of steels available at the time. In service, their averaged best performances across the Atlantic with 14,7000 indicated horsepower from a double expansion three-cylinder reciprocating engine were 18.86 knots westbound (Umbria, May 1885) and 20

knots westbound (Etruria, May 1888). Eleven engineers, one electrician and 109 firemen were employed on board.

These two sisters had hulls divided into ten watertight compartments, with most of the bulkheads extending to Upper Deck which necessitated watertight and fire doors to be provided for access. The ships catered for 550 First class and 800 Second class passengers, and their accommodations were especially considered and ornately executed, with stained glass cupolas, heavy carved furniture, velvet drapes and expensive fixtures leading to their being described as ‘floating hotels’. Umbria and Etruria were impressivelooking ships dominated by two huge funnels and three masts.

Cunard and his steamers ruled the Atlantic unchallenged until 1850, when a newcomer emerged on the scene. Cunard steamers sailed from Liverpool and crossed the North Atlantic, calling first at Halifax, Nova Scotia in Canada, before proceeding to Boston in the United States. This meant that the transatlantic post took a day longer to reach Americans, and, while a major seaport, Boston was not considered to be the economic hub of the country. This was New York, and post was additionally delayed in reaching there from Boston.

ABOVE The First Class Smoking Room onboard the Umbria and Etruria.

RIGHT Second Class Smoking Room on board Umbria and Etruria.

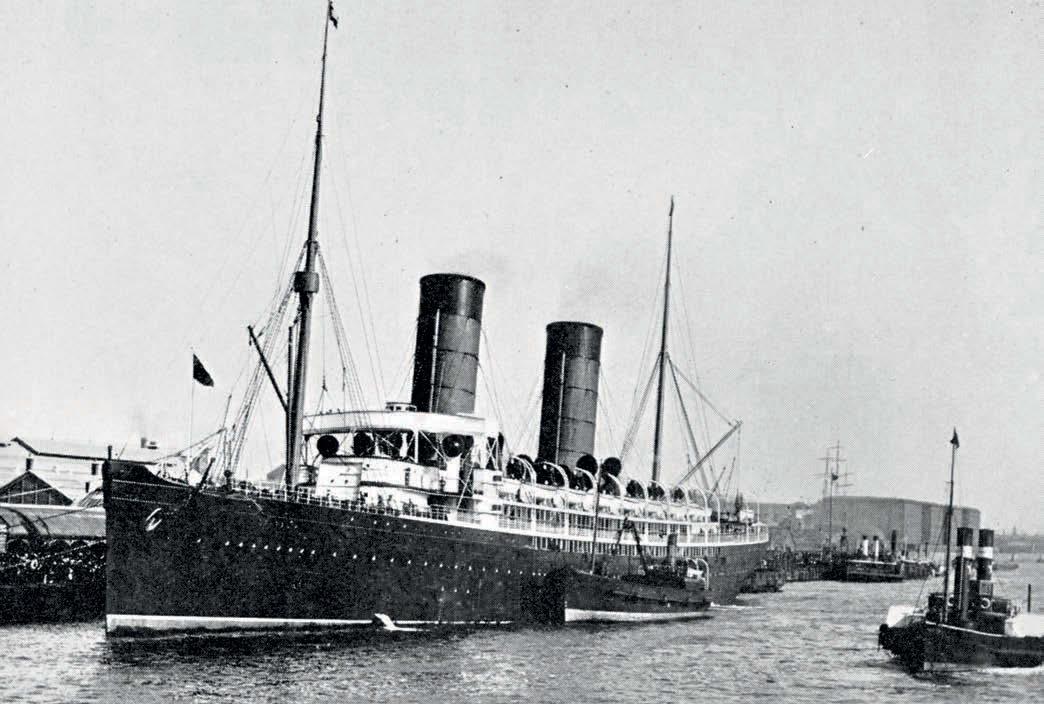

BELOW When Cunard’s Campania joined the fleet in 1893 she heralded a new era of speed, comfort and amenities.

ABOVE Campania and Lucania had elegant wood-panelled First class Smoking Rooms. ABOVE The First class Assembly Hall on Campania and Lucania were arranged around a large skylight that led to the First Class Dining Room.

Anticipating that this situation offered a possible business opportunity for a direct steamship service between Britain and New York, the American shipowner Edward Knight Collins successfully bid for a tender offered by the US Postmaster General. Since 1836 Collins had operated sailing ships between New York and Liverpool and it was a logical step to upgrade the service with a fleet of steamships. Thus, the Collins Line was founded and began fortnightly sailings in 1850 with four steamers that were bigger and faster than Cunard’s. The ships were also more luxurious than the Cunarders, but their high operating costs meant that they were not particularly profitable.

However, while the American government increased its operating subsidy, a series of accidents dented public confidence and in 1958 Collins Line folded. Other transient challenges came from Inman Line and Guion Line, but a new more persistent challenge emerged when the British Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, known

Lucania presents a powerful impression, not least from her two huge fuunels.

as the White Star Line, began services with three well-found steamers in 1872.

Speed was always a selling point on the Atlantic, and the three ships each held the record for the fastest crossing, the record being popularly known as the Blue Riband of the Atlantic. Further record breakers were built for White Star before the cost of operating the ships at high speed led to a policy of building moderately fast ships which were bigger and comfortable, leaving speed records to Cunard. Nonetheless, White Star provided a major challenge to Cunard’s dominance and led to the Line having to improve their own ships.

In 1893, nine years after Umbria and Etruria, Cunard introduced a pair of steamers designed to eclipse the competition and re-establish Cunard as the premier steamship line on the Atlantic. Campania and Lucania were of 12,950gt and driven by two five-cylinder triple-expansion engines developing 30,000 shaft horsepower, which gave the ships a service speed of 21 knots. At full speed 132 stokers were required to haul 560 tons of coal a day into 96 boiler furnaces.

Both liners were built by Fairfield Shipbuilding & Engineering Co of Glasgow in Scotland and both held the Blue Riband at different times. They carried carried 600 First class, 400 Second class and 1,000 Third class passengers. The crew totalled 416: 61 in the deck/navigation department, 160 in the hotel department and 195 in the engineering department. Acclaimed as ‘the most magnificently appointed passenger liners in the world’, Campania and Lucania adopted period styles for the decoration of their public spaces and incorporated a magnificent grand staircase linking the First class decks.

For the first time, single occupancy cabins were available and First class children had their own dining room. Perishable provisions were stored in refrigerated hold spaces and, worryingly, open fires were employed in the Lounge and Smoking Room, something which would have constituted a considerable fire risk given the amount of flammables on board. However, for five years the sisters ruled the Atlantic, until new challengers came from continental Europe.

Partial Deck Plan of Umbria and Etruria.

Lucania Campania Upper Decks.

Lucania entered Cunard service in 1894, and she and Campania each held the Blue Riband eastbound and westbound records in turn.