MOTIFS IN ISLAMIC ART A SEARCH FOR ETERNITY

KENT ANTIQUES

ISLAMIC & INDIAN ART

ORIENTALIST PAINTINGS

ISLAMIC & INDIAN ART

ORIENTALIST PAINTINGS

First and foremost, I would like to thank Ms. Hülya Bilgi whose wonderful publication, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection -co-authored by Professor Turgut Saner and Ms. Şebnem Eryavuz- inspired us for the concept of our stand at TEFAF Maastricht 2023, titled: “MotifsinIslamicArt:ASearchforEternity”.

We are indebted to many distinguished experts and scholars for their assistance during the preparation of this catalogue. Special thanks are due to Dr. Julian Raby who has generously shared his opinion on various matters, and Ms. Mina Moraitou of the Benaki Museum, Athens, for kindly permitting us to use a photograph of the 1925 Alexandria Islamic Art exhibition (Exposition d’Art Musulman) from their archive. We are also grateful to Persian and Indian miniature painting specialist Ms. Margaret Erskine for preparing the material we have used in the catalogue entry of the illustrated folio from Hafiz Abru’s Majma‘ al-Tawarikh and the Mughal miniature painting titled AConqueror,Possibly Alexander the Great. I also would like to thank Ms. Nahla Nassar and Dr. Qaisra Khan for helping us acquire detailed photographs of the Ottoman enamelled dagger and scabbard (Accession No. JLY 1748) in the Professor Sir Nasser D. Khalili Collection which we have compared to our enamelled dagger and scabbard.

I would also like to take this opportunity to express my thanks to my brother Dr. Bora Keskiner who did extensive research and wrote the texts. The effective presentation of the art works would not have been possible without the participation of Mr. Peter Keenan, Mr. Richard Harris, and fine art photographer Mr. Richard Valencia.

Mehmet Keskiner DirectorThis year, we prepared a very special exhibition for TEFAF Maastricht 2023, titled “MotifsinIslamicArt:ASearchforEternity” which is accompanied by this catalogue specially designed and authored according to this concept. The concept is based on demonstrating the extraordinary richness and variety of motifs in Islamic art and explaining their meaning and historical background through the art works in this catalogue.

For this concept we were inspired by a wonderful publication, titled Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection, written by Ms. Hülya Bilgi, Professor Turgut Saner and Ms. Şebnem Eryavuz, published in 2020 by the Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the museum’s foundation.

We will exhibit, between 11-19 March 2023, selected works of art decorated with some of the most interesting and significant motifs used in Islamic art. Each different motif on each piece is highlighted in its catalogue entry with its drawing to emphasize its shape. To create a solid conceptual framework, information has been provided about each motif’s historical background and symbolic meaning.

Our selection includes fine and rare examples of Abbasid Qur’an folios in kufic script written on vellum, Iznik ceramics, an early Mamluk silver-inlaid brass candlestick, an illustrated folio from the Timurid historian Hafiz Abru’s Majma‘al-Tawarikh, a Mughal imperial-quality jade pendant bearing the Throne Verse (Ayat al-Kursi) from the Qur’an, an Ottoman gem-set brooch with the imperial coat of arms, a 17th century Safavid bowl decorated with King Khusraw and Princess Shirin, hunting and sufi scenes; a Qajar painting of “APersianNobleLadyasanAcrobat

PerformingaHandstand” associated with Fath ‘Ali Shah’s (r. 1797-1834) patronage, as well as rare and important examples of Islamic textiles and metalwork. At our stand, we will also exhibit selected paintings by renowned Orientalist painters such as Gianantonio Guardi and Antonie-Ignace Melling.

Kent Antiques is a leading art gallery specializing in Islamic and Indian works of art & Orientalist paintings. The company’s clients include leading world museums, major institutions as well as private collectors. All works of art offered by Kent Antiques is ethically obtained from national and international private collections and trade. Besides the quality and condition, one of our primary concerns is the provenance of the artworks we offer. The provenance of every single piece is checked. We try to obtain as much information and/or documentation as possible from previous owners to support the provenance and make sure none of the artworks were exported from their country of origin in recent years. The authenticity of every single work of art offered for sale is guaranteed and certificate of authenticity is provided on request. Utmost attention is paid to provide genuine art works of highest quality in good condition. The company is active since 1997, in South Kensington, London. Kent Antiques is a member of BADA Organisation and SNA France.

I am delighted to present collectors and museums our TEFAF Maastricht 2023 selection which has been gathered with extreme care for their quality, provenance and condition.

If you need any further information, I will be happy to oblige.

Mehmet Keskiner DirectorDimensions: 23 x 32.7 cm.

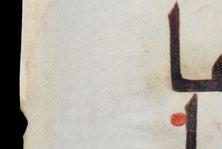

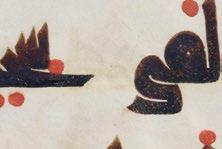

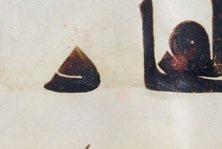

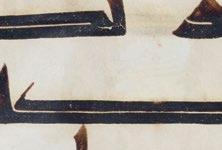

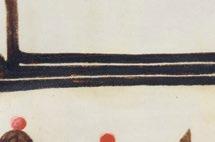

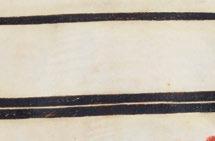

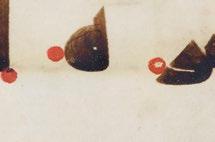

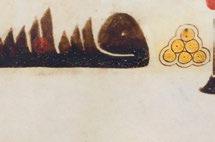

Arabic manuscript on vellum, each side with 7 lines strong and elegant sepia kufic, verses marked with pyramids of gold dots, gold rosette marker at the end of the fifth line indicating the tenth verse of the surah and inscribed ‘ashara in kufic script, diacritics and vowels points indicated by red dots, numbered in the outer margins in Arabic numerals, framed.

Text:

The Qur’an 83: 7-12 (Surah al-Mutaffifin from the middle of verse 7 to middle of verse 12).

Translation:

“[But no! the] wicked are certainly bound for Sijjin and what will make you realize what Sijjin is? A fate already sealed. Woe on that day to the deniers, those who deny the day of judgment. None would [deny it …].”

The horizontally elongated letters seen here are characteristic of early kufic Qur’ans on vellum, and the elongations are thought to be a response to the rectangular page format. The angular script is moderated by the roundness of several letters -such as fa, qaf, waw - that look like large black dots; their inner blank spaces reduced almost to a needlepoint.

This Qur’an folio comes from one of the finest Qur’an manuscripts in kufic script. A section of this Qur’an is in the Iran Bastan Museum (Inv. No. 4289), Tehran. Please see, Martin Lings, The Qur’anic Art of Calligraphy and Illumination, Westerham, 1976, no. 5.

A folio from the same manuscript, in the Ithra Archive, is published in The Art of Orientation - An Exploration of the Mosque through Objects, Edited and Written by Dr. Idries Trevathan et al, Ithra, Hirmer, Munich, 2020, p. 119.

Provenance: Private UK Collection

Dimensions: 23.2 x 32.7 cm.

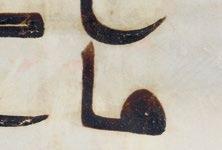

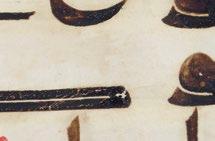

Arabic manuscript on vellum, each side with 7 lines strong and elegant sepia kufic, verses marked with pyramids of gold dots, a gold khams marker in the form of a gold ha, diacritics and vowels points indicated by red dots, numbered in the outer margins in Arabic numerals, framed.

Text:

The Qur’an 92:5-10 (Surah al-Layl Middle of verse 5 to end of verse 10)

Translation:

“[As for the one] who is charitable, mindful of Allah, and firmly believes in the finest reward, We will facilitate for them the way of ease.”

The horizontally elongated letters seen here are characteristic of early kufic Qur’ans on vellum, and the elongations are thought to be a response to the rectangular page format. The angular script is moderated by the roundness of several letters -such as fa, qaf, waw - that look like large black dots; their inner blank spaces reduced almost to a needlepoint.

This Qur’an folio comes from one of the finest Qur’an manuscripts in kufic script. A section of this Qur’an is in the Iran Bastan Museum (Inv. No. 4289), Tehran. Please see, Martin Lings, The Qur’anic Art of Calligraphy and Illumination, Westerham, 1976, no. 5.

A folio from the same manuscript, in the Ithra Archive, is published in The Art of Orientation - An Exploration of the Mosque through Objects, Edited and Written by Dr. Idries Trevathan et al, Ithra, Hirmer, Munich, 2020, p. 119.

Provenance: Private UK Collection

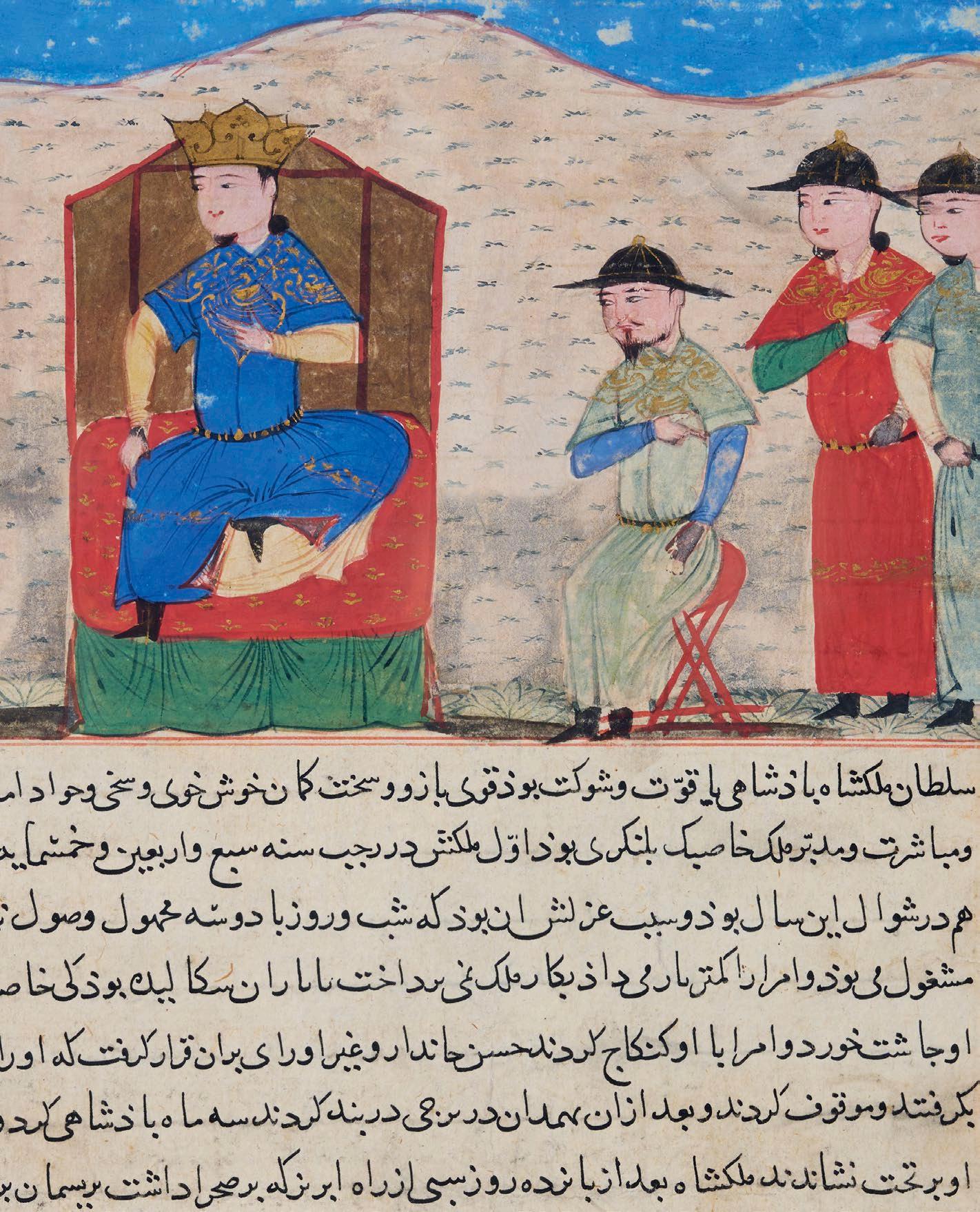

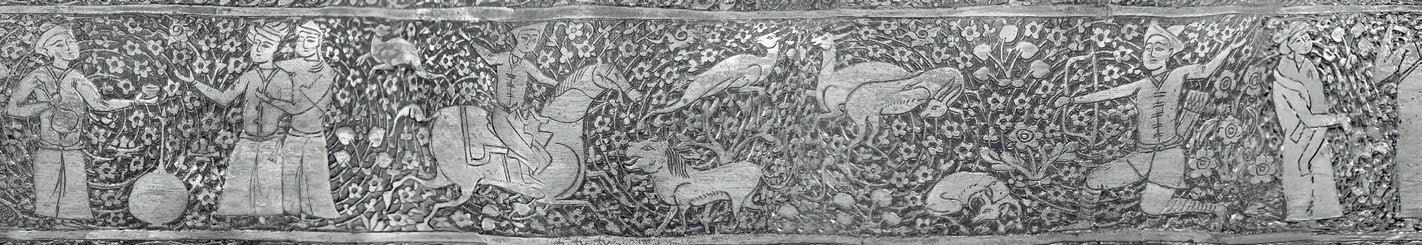

Timurid Empire

Circa 1425

Dimensions:

Painting 14 x 25.5 cm. Page 43 x 33 cm.

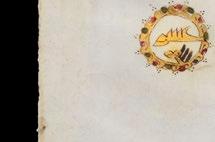

The Seljuk ruler Sultan Malik Shah III (r. 1152-1153) enthroned in a landscape surrounded by viziers and courtiers, an illustration to the Majma‘ al-Tawarikh, Herat, c. 1425, gouache on paper with highlights in gold, written in twentyone lines of black naskh script, margin lines in red and blue, naskh text on the reverse.

Since time began, rulers across the globe have commissioned records of important events past and present. The Timurid dynasty, founded by Timur (Tamerlane) in 1370 was no exception with historians, scribes and artists fully occupied in the Timurid libraries and studios. Hence the Majma‘ alTawarikh (Collection of Histories) was commissioned and this particular folio depicts the Seljuk ruler Malik Shah III (r.1152-1153) whose short reign lasted barely a year. The unillustrated verso relates to the reign of his predecessor Sultan Mas’ud (r. 1134-1152).

There are two known copies of the Majma‘ al-Tawarikh. The first is in the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul with the second, a dispersed copy, containing this particular folio and fitting in style to the painting of Herat, c. 1425. Opportunities to acquire Oriental manuscripts abounded at the beginning of the last century, often in Paris, with the likes of Demotte, Vever, Kevorkian and Tabbagh eager to add to their collections, with The Metropolitan Museum, The Walters Art Gallery and The Los Angeles County Museum being modern day recipients. Such opportunities are not as plentiful in the twenty-first century making this an exciting and rare occasion for the modern-day collector or institution.

The text on the reverse ends with the year 547 A.H. (1152 C.E.), the year Sultan Malik Shah III was enthroned. At the bottom of the page the names of Malik Shah’s viziers are listed as follows: Sharaf al-Din Anushirvan b. Khalid Kashi, Imad al-Din Abu al-Barakat Darguzini, Kamal al-Din Muhammad al-Hazin, Izz al-Mulk Barujurdi, Muayyad al-Din Tughrai, Taj al-Din Shirazi, Shams al-Din Abu-Najib, Manguvarir, Nanar, Abd al-Rahman, Khas-Beg Jangari.

The Author

The famed Timurid historian Hafez-e Abru (d. 1430) was tasked by Shahrukh (r. 1405-1447), Timur’s youngest son, with the commission of the Majma‘ al-Tawarikh, a continuation of the famous Jami‘ alTawarikh by the celebrated Ilkhanid historian-vizier Rashid al-Din. Hafez-e Abru was born in Khorasan and studied in Hamadan before moving to Herat where he flourished working for the Timurid court.

The Patron

The Timurid Empire spanning Central Asia controlled most of the main trade routes between Asia and Europe including the famed Silk Road, bringing great wealth to the region. The patron of the Jami‘ al-Tawarikh is Sultan Sharukh (r. 1405-1447). He established his capital in Herat rather than Timur’s Samarqand and with his third son Prince Baysunghur (1397-1434), was an exceptional patron of the arts. Shahrukh was eager to commission histories of the Timurid ancestors and Baysunghur established an important library and atelier at Herat, worthy of Timur and his empire.

Further Reading:

E. Binney, IslamicArtfromtheCollectionofEdwinBinney,3rd., Portland, 1962. Ernst J. Grube, The World of Islam, London, 1966.

B. W. Robinson, Rothschild and Binney Collections: Persian and Mughal Arts of the Book, Persian and Mughal Art, P & D Conaghi Exhibition Catalalogue, London, 1976, pp.13 and 22, no. 11.

Sotheby’s Sale of Fine Oriental Miniatures, Manuscripts, Qajar Paintings and Lacquer, London, 2 May, 1977, lot 164.

Abolala Soudavar, Art of the Persian Courts, New York, 1992, pp. 64-66.

On the reverse, the folio bears an old French customs stamp which reads “Douane Centrale”. This is the same stamp found on the folio from the Majma‘ al-Tawarikh, from the Emile Tabbagh collection, now preserved in the Smithsonian / Arthur M. Sackler Gallery / National Museum of Asian Art (Accession Number S1986.131). Please see, https://asia.si.edu/object/ S1986.131/

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Margaret Erskine for writing this article on the present folio from Hafiz Abru’s Majma‘ al-Tawarikh.

Ex-Private French Collection, Poitiers.

The father of the French collector who owned this folio was actively collecting between 1920s and 1940s. They both were very connected to the Parisian artistic circles and the art market. It is not possible to give the precise date of the acquisition of the present folio, but since most pages from this famous manuscript appeared on the French market between 1928 and 1933, dispersed by the famous collector Emile Tabbagh, it was probably bought by the collector’s father during this period, in 1930s or 1940s. On the reverse, our folio bears an old French customs stamp which supports the Emile Tabbagh connection. This is the same customs stamp found on the folio from the Majma‘ al-Tawarikh, from the Emile Tabbagh collection, now preserved in the Smithsonian / Arthur M. Sackler Gallery / National Museum of Asian Art (Accession Number S1986.131). Please see, https://asia.si.edu/ object/S1986.131/

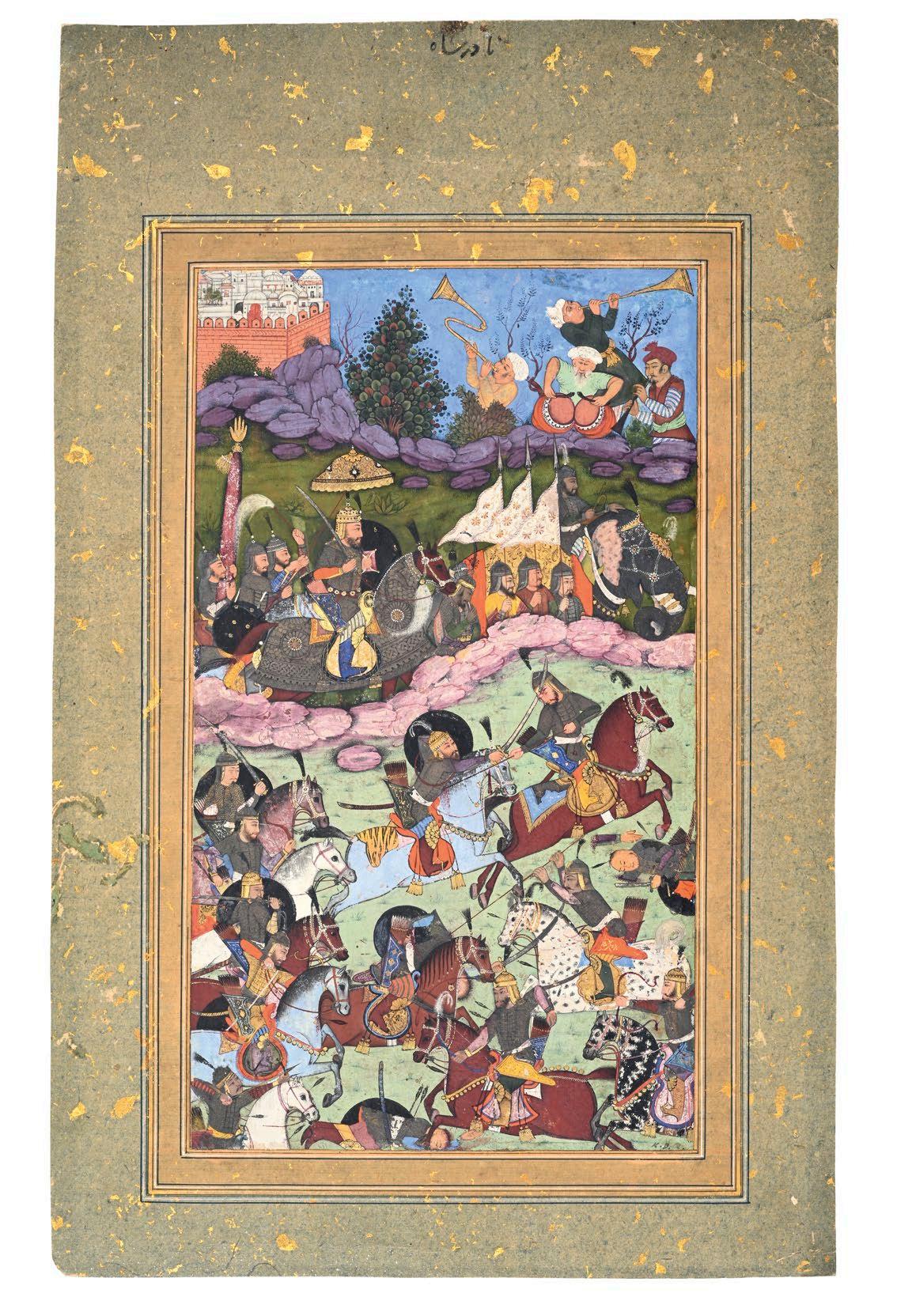

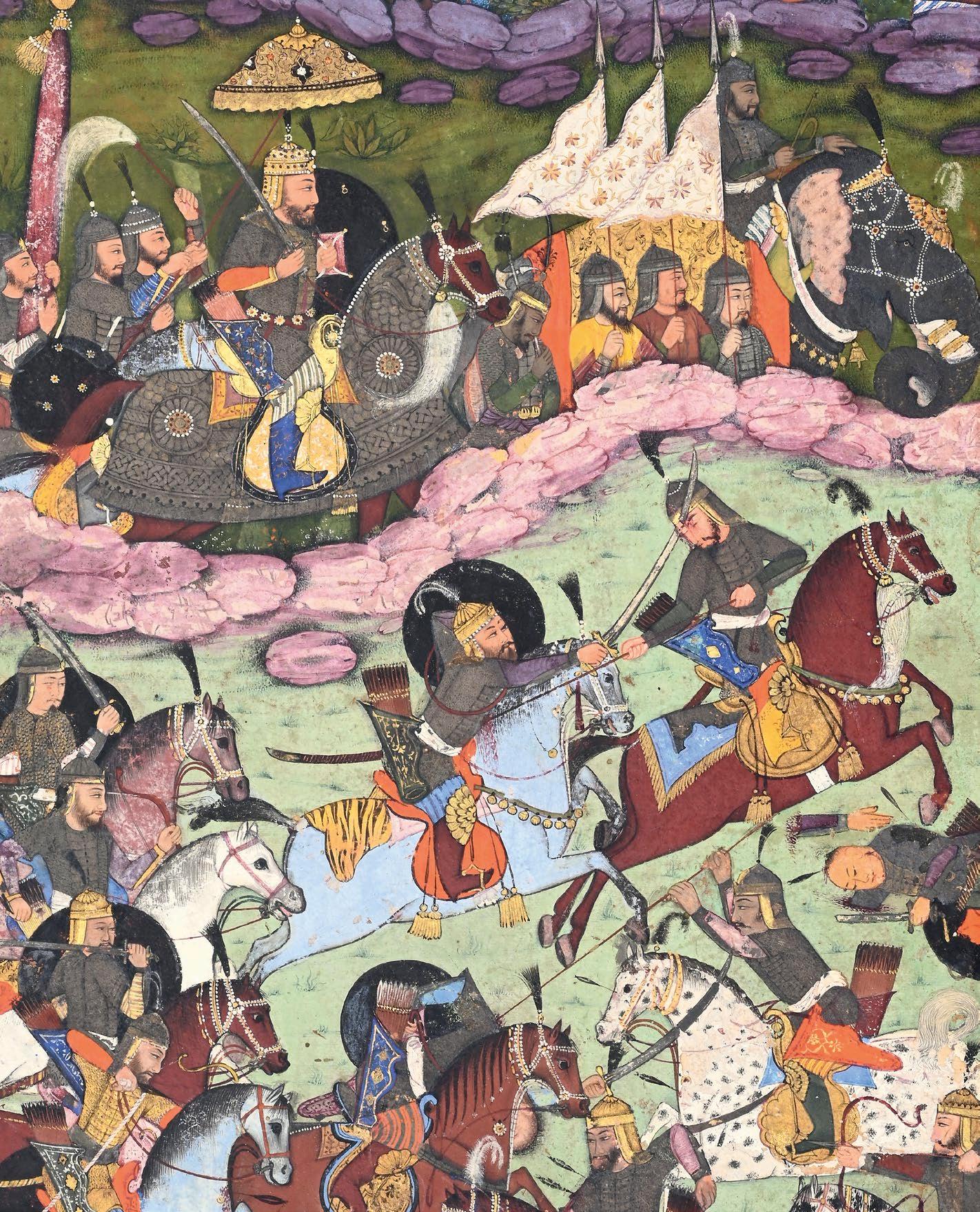

Folio: 37.3 x 23.3 cm.

Miniature: 26 x 15.5 cm.

Opaque watercolour, ink, heightened with gold on paper.

Mounted on an album page with gilt-sprinkled borders. Inscribed at a later stage ‘Nadir Shah’, in nasta‘liq script, on the outside mount.

A conqueror, possibly Alexander the Great, leading his army across a rocky hillside, surrounded by an entourage. Alexander depicted on horseback shaded by a gold parasol, the horse fully armoured, banner bearers lead the procession following a mahout (elephant rider) astride a fully caparisoned elephant.

In the foreground soldiers on horseback charge in battle brandishing swords and arrows. Musicians performing in full unison against a vivid blue sky, a Mughal palace in the distance beyond.

There are a few details which may support the identification of our conqueror as Alexander the Great (r. 336-323 B.C.E.), known as Iskandar in Muslim lands, who founded an empire that spanned from Greece to the north west of India. Alexander’s first confrontation with war elephants occurred at the Battle of Gaugamela (331 B.C.E.) where the Persians deployed fifteen elephants. Alexander won at Gaugamela, and as he was deeply impressed by the enemy elephants which he later took into his own army. In the present miniature, the elephant leading Alexander’s entourage may be linked to this historical anecdote.

Legend has it that Alexander’s third and last wish before he died was that both his hands be kept out of his coffin; he said he wished people to know that ‘he came empty-handed into this world and empty-handed he left this world’. The standard with a finial in hand form, behind Alexander, might be related to this last wish of his.

Alexander’s military campaigns were chronicled in poet Nizami’s Khamsa (Quintet) in the Iskandernāma (the Alexander Romance) and Ferdowsi’s Shahnāma and were popular subjects in Mughal painting. The ‘Alexander Romance’ which had an impact on Muslim poetry, probably took shape in Alexandria between the 3rd century B.C.E. and the 3rd century C.E. Exactly how the tale reached Persian and Indian oral and literary

traditions is not clear. In this tradition Alexander is portrayed a world hero and sometimes as a sage. See, G. Cary, The Medieval Alexander, Cambridge, 1956.

Nizami’s Alexander Romance, completed in 1202 C.E., is divided into two books entitled Sharafnāma and Iqbalnāma. These include a new, Muslim interpretation of Alexander’s story. According to Nizami, Alexander’s first teacher is Nichomachus and Artistotle is his classmate. On his father Philip’s death Alexander becomes king and soon goes to the rescue of the Egyptians who have been attacked by an enemy. He returns victorious and decides to cease paying tribute to the Persian king Dārā. Their armies meet in battle and two traitorous officers slay Dārā. One of Dārā’s dying wishes is that Alexander marry his daughter Rowshanak.

Now that Alexander is king of Persia, he sets out to destroy the fire temples of the Zoroastrians. He marries Rowshanak but since he wants to travel the world, he sends her back to Anatolia along with his treasure for safety’s sake. He first receives the submission of the Arab lands, and visits the holy Kăba. From there he travels to the land of Bardăwhere he meets Queen Nūshāba, who rules over a court of women. He returns to the East and subdues the fortress of Darband, and then a fortress called Sarīr. He explores the cave of Kay Khosrow and then continues east to India. The Indian king Keyd makes peace by sending the four gifts mentioned by Ferdowsi, and Alexander proceeds thence to China. After considerable negotiations, and a contest between the Greek and Chinese painters, the Chinese emperor submits with dignity to Alexander. He now begins the homeward journey, via the Qipchaq plain and the Russian lands, against whom Alexander must fight seven battles before subduing them.

Alexander’s last major adventure before reaching Anatolia is his visit to the ‘land of darkness’ in search of the water of life. Khizr is his guide, and the results are always the same: Khizr drinks from the spring and becomes immortal and Alexander loses his way and never finds the elixir. The Sharaf-nāma ends when Alexander reaches Anatolia. See, William N. Hanaway, “Eskandar-nāma”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VIII, Fasc. 6, pp. 609-612.

Body armour for horses, known as barding and depicted in this painting on the horse of the main figure, was used during Alexander’s reign and went onto to influence armies in the centuries to come from India to Europe and North Africa.

The Indian love for horses and battle scenes gave plenty of scope not only for the Mughal schools but the Deccani and Rajput studios too. Examples of full body armour are rare but can be found in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Wallace Collection, London and the Royal Armouries in Leeds.

The term ‘Sub-Imperial’ Mughal was used by the eminent scholar of Indian painting, W. G. Archer who used the phrase to describe artists who worked outside the Mughal court for wealthy patrons, both Muslim and Hindu. The choice of subject gives clues to the identity of the patron and in the case of this painting, the patron is likely to be Muslim. A similar battle scene, dated 1608 C.E. from the collection of Edwin Binney 3rd is now in the San Diego Museum of Art. See E. Binney, Indian Miniatue Paintings from The Collection of Edwin

Binney, 3rd, The Mughal and Deccani Schools with Some Related Sultanate Material, Portland Art Museum, Oregon, 1973, no. 32. There are also illustrated SubImperial Mughal manuscripts in the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin. For further discussion, please see Linda York Leach, Mughal and Other Indian Paintings, Dublin, 1995, Vol. II, pp. 529-533.

Acknowledgment:

We would like to thank Margaret Erskine for her expert advice and kind preparation of the material we have used in this catalogue description.

Provenance:

Sotheby’s New York, 21 March, 1990, Lot 48. Acquired by Prominent East Coast Collector, Until 2021. Christie’s New York, 17 March 2021, Lot 435.

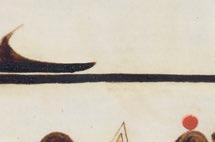

Fritware, the body of globular form supported on a broad foot-ring, the high cylindrical neck slightly everted toward the rim, an s-shaped handle ring from the rim to the shoulder, painted in underglaze with white and turquoise Chinese clouds on a cobalt blue ground.

The cloud motifs on the present jug have been identified as a subgroup of Chinese clouds and named the “S-cloud motif” by Nurhan Atasoy and Julian Raby. Please see, Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, Alexandria Press, London, 1989, p. 259, No. 549. This motif is first recorded as a border device on a ‘Baba Nakkaş’ candlestick (illustrated in Ibid, No. 60, p. 81), datable to Circa 1480, but it seems to have vanished from Iznik potters’ repertoire after 1540. In Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, Atasoy and Raby show the present jug as the last recorded example which is decorated with the “S-cloud motif”. Ibid, p. 259.

The stylised cloud band motif is one of the most favoured motifs of the Ottoman decorative repertoire; frequently used by the artist members of the palace workshop (nakkaşhâne) in the 16th century. Chinese clouds were widely used to decorate Ottoman ceramics, textiles, manuscripts, carpets, glass and woodwork. In Chinese art, this motif is primarily associated with the strength of the dragon and represents the smoke coming out of its mouth. However, in Ottoman art, it was generally interpreted as a stylized cloud in the sky. İnci Ayan Birol, “Tezhip”, TürkiyeDiyanetVakfıİslamAnsiklopedisi, vol. 41, 2012, pp. 6568. In the present example, for instance, this appears to be the reason why the potter used blue for the background and white for the clouds.

The cloud band motif were much favoured by Timurid and Akkoyunlu artists. Diverse cloud motifs found in miniature paintings of the Herat and Shiraz schools, on ceramics, metalware and carpets appear to have been adopted by Ottoman artists. For further information please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, p. 118.

Iznik jugs in the form of the present piece were first produced in circa 1520. See, Julian Raby & Nurhan Atasoy, Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, Alexandria Press, London, 1989, p. 39. The present jug is an extremely rare and important example of early Iznik ceramic production, displaying true iconic aesthetic and presence.

After Bernard Rackham, Islamic PotteryandItalianMaiolica, Faber and Faber, London, 1959, pl. 37, No. 73.

After Julian Raby & Nurhan Atasoy, Iznik:ThePotteryofOttoman Turkey, Alexandria Press, London, 1989, p. 259, pl. 549.

Provenance:

Ex-Adda Collection

Ex-Kelekian Collection

Labels at the Base:

-Exhibition Label: 1910 Munich Exhibition

-Collection Label: “Kelekian No. 19”

Exhibition:

Exhibited in Munich, at the Masterpieces of Islamic Art (Meisterwerken Muhammedanischer Kunst) exhibition in 1910, catalogued in Meisterwerken Muhammedanischer Kunst, No. 1528 (R. 68).

Exhibited in Alexandria, at the Exposition d’Art Musulman, Les Amis de l’Art, Alexandrie, in 1925. (please see the photograph above)

Literature:

-Published in Julian Raby & Nurhan Atasoy, Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, Alexandria Press, London, 1989, p. 259, pl. 549.

-Published in Bernard Rackham, Islamic Pottery and Italian Maiolica, Faber and Faber, London, 1959, pl. 37, No. 73.

The Kelekian Collection label and the 1910 Munich ʻMasterpieces of Islamic Art’ Exhibition label at the bottom of the jug. The present jug in the 1925 Alexandria Islamic Art Exhibition (Exposition d’Art Musulman) Image courtesy of the Benaki MuseumFritware, the body of rounded form set on a pedestal foot, dome-shaped cover with a bud-form finial set on the top, underglaze painted in cobalt blue, relief red, green and outlined in black with saz leaves and rumi sprouts, a band of key-fret patterning at junction between bowl and cover.

The saz leaf seen on our footed bowl, is an important motif frequently used by the artists employed in the Ottoman court studio. The first representative of the saz style at the Ottoman palace was Şahkulu, an artist brought from Tabriz by Sultan Selim I (r. 1512-1520). This style was a departure from the classical miniature painting, characterised by pictures drawn with a brush in black ink, featuring long pointed leaves, giving birth to the term ‘saz leaf’. Paintings in the saz style may remind a thick forest with intertwined curved leaves and khatai blossoms. In fact, the word saz, used to mean ‘forest’ in the Dede Korkut stories that date back to the 10th or 11th century. For further information please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, p. 106.

The present bowl with cover belongs to a small group of Izniks and there are only a few recorded comparable examples. An Iznik bowl and cover in similar form is in the British Museum (Museum number: FBIs-5), London. Please see: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/ object/W_FBIs-5

A second closely related example is in the Louvre Museum (Inv. No. 7880/101-2), Paris. Please see, Julian Raby & Nurhan Atasoy, Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, Alexandria Press, London, 1989, p. 339, pl 742. Lastly, a comparable Iznik footed bowl and cover in similar form is in the Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul. Please see, Hülya Bilgi, Ateşin Oyunu – Sadberk Hanım MüzesiveÖmerKoçKoleksiyonlarındanİznikÇini

ve Seramikleri, Vehbi Koç Vakfı, İstanbul, 2009, pp. 398-399.

Provenance: Ex-Private French Collection

Ottoman Empire

Second half of the 16th Century

Height: 22.5 cm.

Fritware, with bulbous body, slightly flaring neck and s-shaped handle. Decorated in blue, green and coral red, on the body and the neck, with delphiniums and carnations. Narrow band of wave motifs around the rim.

This jug, with its delphiniums and carnation motifs, is an excellent example of the use of flowers in Ottoman decorative repertoire. Delphiniums, hyacinths and carnations, much favoured by the artists working in the 16th century Ottoman palace workshops (nakkaşhane), were used in the decoration of Iznik ceramics as well as imperial silks and velvets. Please see Ara Altun & Belgin

Arlı’s Tiles – Treasures of Anatolian Soil – Ottoman Period, Kale Group Cultural Publications, Istanbul, 2008, fig. 140, p. 135 and Michael Rogers’ Topkapı: Costumes, Embroideries and other Textiles, Thames & Hudson, London, 1989, pl. 22.

Like the tulip and rose, the carnation is one of the flowers frequently mentioned in Ottoman court poetry where it is likened to the face or cheek of the beloved. From the second half of the 16th century carnations are one of the most widely used motifs in designs by palace artists for fabrics, embroideries, tiles and ceramic ware. In Iznik ceramic decoration the thickly applied coral red so characteristic of this ware is used also for carnations as can be seen on the present jug. For further information please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, pp. 98-99.

A comparable Iznik dish decorated with delphinium sprouts is in the David Collection, Copenhagen. Please see, Julian Raby & Nurhan Atasoy, Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, Alexandria Press, London, 1989, p. 235, pl 428.

Provenance:

Ex-Émile Tabbagh Collection, Paris.

Émile Tabbagh (d. 1936 ?)

Émile Tabbagh was a renowned dealer-collector. A catalogued sale of his famous collection took place in 3-4 January 1936, at Anderson Galleries, in New York. The title of the sale catalogue is A Magnificent Collection of Near Eastern and Early Mediterranean

Art: Ceramics, Miniatures, Oriental Rugs, Ancient Glass – Property oftheEstateoftheLateÉmileTabbagh,ParisandNewYork, American Art Association Anderson Galleries (30 East 57th Street New York), 3-4 January 1936. Please see this link for the PDF of the Émile Tabbagh Collection sale catalogue: https:// ia904508.us.archive.org/30/items/magnificentcolle00amer/ magnificentcolle00amer.pdf

Fritware, underglaze painted in cobalt blue, coral red, green, black. The central red roundel is surrounded by eight, intertwined white rumis, encircled by a blue and green border on the rim.

The rumi motif has a special place in traditional Ottoman patterns. This motif is called rumi by the Ottomans, islimi by the Persianate dynasties and arabesque by the Europeans. There are divergent views on the origin of this motif, some regarding it floral in origin, others as zoomorphic, such as the theory that it derives from the wings of birds or mythical animals in central Asian art. The motif developed in Samarra in the 9th century and spread to the Islamic lands, becoming a dominant feature in Karahanid, Ghaznavid, Fatimid, Abbasid, Andalusian Umayyad and Mamluk art and above all becoming popular in Anatolia, also known as Rum, from which the name rumi derives. Some outstanding examples of rumi motifs are found in Anatolian Seljuk stone carving and woodwork usually combined with lotus and palmette motifs. For further information please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, p. 174. For a collection of compositions with rumis please see, Owen Jones. The Grammar of Ornament – A Unique Collection of Classical Designs from Around the World, Girard & Steward, 1856, pl. 36-38.

In the present dish, the rotating rumis form a ‘wheel of fortune’ motif which symbolises movement and transformation because of its endless turning movement. This motif has been used throughout the world since antiquity and although its meaning has varied from culture to culture it has principally symbolized various cosmic elements associated with the cycle

of life. For further information please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, pp. 46-49.

Comparable Iznik dishes decorated rotating central designs can be seen in the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation Museum (Inv. No. 819), Lisbon, Fitzwilliam museum (Inv. No. C.30-1911), Cambridge, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Inv. no. 1971-23). Please see, Julian Raby & Nurhan Atasoy, Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, Alexandria Press, London, 1989, p. 243, pl. 466, 467, 468.

Provenance:

Ex-Adda Collection (Adda Collection Sale Catalogue, Collection d’un Grand Amateur, Palais Galliera, 1965, Lot 859.)

Fritware, underglaze painted in blue, coral red, green, black. Decorated with rotating red tulips around a central flower head, the rim with blue double-tulip motifs and red flower heads.

The tulip has a symbolic meaning in Ottoman art. The letters of the word tulip (Lâle [ هللا]) in Turkish and Persian are the same letters used for writing the word Allah [ اللَّه] (God). These two words have the same numerological value in the abjad system (a decimal alphabetic numeral system in which the twenty-eight letters of the Arabic alphabet are assigned numerical values). Tulip is one of the leading decorative elements in Ottoman art; frequently used together with roses, hyacinths, saz leaves. It is also used with khatai blossoms as can be seen in the present dish. Tulip also played a role in imagery in Ottoman poetry. In many poems, tulip leaves are likened to the cheeks of the beloved. The word lāleh-khad (lâle-had), often used in Ottoman poetry, means ‘tulip-cheeked’. Tulips were among the most favoured motifs used in the Ottoman court workshops in the 16th century. The name ‘tulip’ is thought to have derived from the Turkish word tülbend (from the Persian word دنبلد [dulband]) -meaning ‘large cotton band which is used in the making of turban or headgear’- because of the fancied resemblance of the flower to a turban.

During the 16th and 17th centuries interest in tulip breeding grew in Istanbul and şükûfenâmes (books on flowers) and treatises were written about tulips. For further information please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, pp. 90-93.

In the present dish, the rotating tulips form a ‘wheel of fortune’ motif which symbolises movement and transformation because of its endless turning movement. This motif has been used throughout the world since antiquity and although its meaning has varied from culture to culture it has principally symbolized various cosmic elements associated with the cycle of life. For further information please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, pp. 46-49.

A related Iznik dish decorated with rotating tulips is in the Ömer M. Koç Collection. Please see, Hülya Bilgi, AteşinOyunu–SadberkHanımMüzesiveÖmerM.Koç KoleksiyonlarındanİznikÇiniveSeramikleri, Vehbi Koç Vakfı, İstanbul, 2009, p. 280, pl. 164.

Comparable Iznik dishes decorated rotating central designs can be seen in the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation Museum (Inv. No. 819), Lisbon, Fitzwilliam museum (Inv. No. C.30-1911), Cambridge, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Inv. no. 1971-23). Please see, Julian Raby & Nurhan Atasoy, Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, Alexandria Press, London, 1989, p. 243, pl. 466, 467, 468.

Provenance: Ex-Monsieur B. Collection, Paris. Ex-Private Belgian Collection.

Fritware, underglaze painted in cobalt blue, coral red, green, black. Decorated with bunches of red and blue spring flowers, the rim with blue double-tulip motifs and flower heads.

In the Ottoman period flowers, decorating the present dish, were a constant part of daily life, grown in gardens everywhere, from palaces to humble homes. Flowers were blessed reminders of the gardens of heaven. Foreign travellers and ambassadors who visited the empire frequently remarked about this love of flowers. The 17th century Ottoman writer and traveller Evliya Çelebi describes how vases of roses, tulips, hyacinths, narcissi and lilies were placed between the rows of worshippers in the Eski Mosque and the Üç Şerefeli Mosque in Edirne, and how their scent filled the prayer halls. As depicted in the present dish, vases of flowers adorned niches in the walls, dining trays and rows of vases were placed around rooms and pools. For further information please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, pp. 86-90.

The tulip, repeatedly used in rim of our dish, has a symbolic meaning in Ottoman art. The letters of the word tulip (Lâle [ هللا]) in Turkish and Persian are the same letters used for writing the word Allah [ اللَّه] (God). These two words have the same numerological value in the abjad system (a decimal alphabetic numeral system in which the twenty-eight letters of the Arabic alphabet are assigned numerical values). Tulip is one of the leading decorative elements in Ottoman art; frequently used together with roses, hyacinths, saz leaves. It is also used with khatai blossoms as can be seen in the present tile. Tulip also played a role in imagery in Ottoman poetry. In many poems, tulip leaves are likened to the cheeks of the beloved.

The word lāleh-khad (lâle-had), often used in Ottoman poetry, means ‘tulip-cheeked’. Tulips were among the most favoured motifs used in the Ottoman

court workshops in the 16th century. The name ‘tulip’ is thought to have derived from the Turkish word tülbend (from the Persian word دنبلد [dulband]) -meaning ‘large cotton band which is used in the making of turban or headgear’- because of the fancied resemblance of the flower to a turban.

A comparable Iznik dish decorated with almost identical bunches of spring flowers, is in the Louvre Museum (Inv. No. 7880/70), Paris. Please see, Julian Raby & Nurhan Atasoy, Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, Alexandria Press, London, 1989, p. 234, pl 425. The present dish is a rare and important example reflecting both the high quality and awe-inspiring creativity achieved by of Iznik potters.

Provenance:

Ex-Dr. Joseph Chompret Collection. (The present Iznik dish is recorded in Dr. Chompret’s personal collection register, in page 47.)

Dr. Chompret was born in Paris, in 1869. The son of a country doctor, he chose a medical career and obtained his medical degree in 1893. He specialized in stomatology, and invented the ‘syndesmotome’. For many years he was head of the Saint-Louis hospital in Paris. He was a great collector. He was interested in old cutlery, pewter, ivory and medieval enamels. However he was very enthusiastic about ceramics and his collection of French earthenware, Italian majolica and Middle Eastern ceramics is renowned. Doctor Chompret was also a great friend of museums. The Ceramic Museum of Sèvres received 280 pieces, and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs 339 pieces from Dr Chompret’s collection. Between 1931 and 1956 he was the president of the Friends of Sèvres (Amis de Sèvres) association. He died in 1956.

Ottoman Empire Second half of the 16th Century Height: 25 cm.

Fritware, with bulbous body, slightly flaring neck and s-shaped handle. Decorated in cobalt blue, green and coral red, on the body and the neck, with white-red saz leaves, blue tulips, red spring flowers and şemse medallions.

The saz leaf, seen on our jug, is an important motif frequently used by the artists employed in the Ottoman court studio. The first representative of the saz style at the Ottoman palace was Şahkulu, an artist brought from Tabriz by Sultan Selim I (r. 15121520). This style was a departure from the classical miniature painting, characterised by pictures drawn with a brush in black ink, featuring long pointed leaves, giving birth to the term ‘saz leaf’. Paintings in the saz style may remind a thick forest with intertwined curved leaves and khatai blossoms. In fact, the word saz, used to mean ‘forest’ in the Dede Korkut stories that date back to the 10th or 11th century. For further information please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, p. 106.

Stylized medallion motifs are known as şemse in Turkish, a word deriving from the Arabic shams meaning sun. They are used as frame for diverse designs and arranged in various ways that plays a fundamental role in compositional layouts. Foremost among the arts in which şemse medallions have been used is bookbinding. In time these medallions became oval in shape and sometimes pendants were added at both ends. They frequently feature darts drawn around the edges that are assumed to represent sunrays. For further information please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, p. 180.

A comparable Iznik jug decorated with identical şemse medallions is published in Hülya Bilgi, Ateşin Oyunu–SadberkHanımMüzesiveÖmerM.Koç KoleksiyonlarındanİznikÇiniveSeramikleri, Vehbi Koç Vakfı, İstanbul, 2009, p. 153, pl. 66.

Provenance:

Ex-Private French Collection

Ottoman Empire Second Half of the 16th Century Diameter: 30 cm.

Fritware, underglaze painted in coral red, green, blue and black. Depicting a sailing ship with three masts, in open sea. The rim decorated with stylized wave motifs.

Iznik ceramics decorated with sailing ships are rare. Depicting sailing ships was a novelty for the decorative repertoire of Iznik ceramics. According to Nurhan Atasoy and Julian Raby, the ships depicted on these Iznik dishes are European or lateen-rigged ships (ships with a triangular sail set). See, Nurhan Atasoy and Julian Raby, Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, Thames and Hudson, London, 1989, p. 280. Ships which have always been such a vital part of the commercial life and wealth of the Ottoman Empire, and its capital Istanbul, were lovingly used as enriching motifs in Iznik ceramics and textiles. Please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, pp. 210-211.

The wave motif or ‘rocks and waves’ surrounding the rim of the present dish is one of the schematic motifs inspired by nature which is found on Yuan period blue and white Chinese porcelain. The earliest examples with wave borders are found on the ceramics in the socalled potters’ style which were produced from around 1525 onwards. For further information please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, pp. 122-123.

Iznik dishes similarly decorated with sailing ships from the Musée National de la Renaissance have been published in Frédéric Hitzel & Mireille Jacotin’s Iznik –L’Aventure d’Une Collection, Les Céramique Ottomanes du Musée National de la Renaissance, Château d’Écouen, Paris, 2005, pp. 304-305. For a closely related dish in the Ömer Koç Collection, see Hülya Bilgi’s

AteşinOyunu:SadberkHanımMüzesiveÖmerKoç KoleksiyonlarındanİznikÇiniveSeramikleri, Sadberk Hanım Müzesi, İstanbul, 2009, pl. 284.

Provenance:

Ex-Angélique Amandry Collection (1925-2021).

Born in 1925, Angélique Amandry was an archaeologist, art dealer and art collector. She was secretary to the École Française in Athens. Between 1949-1969, she lived in Strasbourg. Between 1969 and 1981 she lived in Athens. Then she moved to Paris where she married Pierre Amandry. After moving to Strasbourg she became an art dealer. She donated the profit from her sales to the widows of war veterans. For ten years, the name of her stand was ‘AZ La Decouvérte’. She acquired some of her first philHellenic pieces in this period. On her return to Athens, she thought of organizing an exhibition to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Greek independence. The exhibition, held in Hilton Athens, was titled ‘Images of French Philhellenism 1820-1840’. Later, she moved to Paris and she published L'Independance Grecque Dans La Faience Francaise Du 19e Siecle in 1982. Later in her life, she continued working as an antique dealer. She died in 2021.

Mid-16th Century

Dimension: 26 x 26.4 cm.

Fritware, painted under clear glaze with cobalt blue and turquoise; the composition consists of intertwined saz leaves and khatai blossoms, each decorated with white flower heads.

The combination of cobalt blue and turquoise seen on the present tile can also be found on the famous Sünnet Odası (Circumcision Room) tiles in the Topkapi Palace Museum, Istanbul. Especially the saz leaves and khatai blossoms on the side panels of the Circumcision Room tiles feature similar use of cobalt blue and turquoise. Please see, Ahmet Ertuğ and Walter Denny, Gardens of Paradise – 16th Century Turkish Ceramic Tile Production, p. 81.

The saz leaf is an important motif frequently used by the artists employed in the Ottoman court studio. The first representative of the saz style at the Ottoman palace was Şahkulu, an artist brought from Tabriz by Sultan Selim I (r. 1512-1520). This style was a departure from the classical miniature painting, characterised by pictures drawn with a brush in black ink, featuring long pointed leaves, giving birth to the term ‘saz leaf’. Paintings in the saz style may remind a thick forest with intertwined curved leaves and khatai blossoms. In fact, the word saz, used to mean ‘forest’ in the Dede Korkut stories that date back to the 10th or 11th century. For further information please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, p. 106.

There are many hypothesis about the origin of the khatai motif. One of these is that this motif was created by an artist who travelled from Herat to China, or that it was inspired by the lotus, but all agree that the name derives from Hitay, a region of China. For further information please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, p. 104.

An important Iznik ‘Damascus style’ dish with similar cobalt blue and turquoise is published in our gallery’s 2017 catalogue Kent Antiques Islamic and Indian Art – Works of Art from the Islamic World and Orientalist Paintings, London, 2017, No. 18.

Comparable Iznik dishes and footed bowls similarly decorated with khatai blossoms in cobalt blue and turquoise, produced between 1545-1550, are published in Nurhan Atasoy & Julian Raby’s Iznik – The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, Alexandria Press, London, 1994, pl. 352 and pl. 358.

Three Iznik tiles, identical to the present tile, are in the Louvre Museum (Inv. No. AD 5971/1, AD 5971/3, AD 5971/4), Paris. Please see, https://collections. louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010332784

A counterpart of the present tile is published in Couleurs d’Orient - Arts et arts de vivre dans l’Empire Ottoman, Catalogue d’exposition, Villa Empain, Fondation Boghossian, Bruxelles, 18 November 2010 - 27 February 2011, p. 47.

A similar tile decorated with saz leaves and flower heads is found in the Cincinnati Museum. Counterparts of the Cincinnati tile are found in the Rüstem Pasha Mosque in Istanbul. See, Ara Altun & Belgin Arlı, Tiles – Treasures of Anatolian Soil – Ottoman Period, Kale Group Cultural Publications, Istanbul, 2008, p. 183, fig. 204.

This is a rare tile displaying wonderful precision in outlining and colours which is a result of masterful brushwork and excellent firing.

Provenance:

A. Jacob Collection (1942-1988), Paris.

Ottoman Empire Second half of the 16th Century

Dimensions: 25 x 25 cm.

Painted under clear glaze with coral red, green, cobalt blue, black; the composition consists of a central vase with blue tulips and spring flowers, surrounded by red tulips from the left and the right.

In the Ottoman period flowers, like those decorating the present tiles, were a constant part of daily life, grown in gardens everywhere, from palaces to humble homes. Foreign travellers and ambassadors who visited the empire frequently remarked about this love of flowers. The 17th century Ottoman writer and traveller Evliya Çelebi describes how vases of roses, tulips, hyacinths, narcissi and lilies were placed between the rows of worshippers in the Eski Mosque and the Üç Şerefeli Mosque in Edirne, and how their scent filled the prayer halls. As depicted in the present tiles, vases of flowers adorned niches in the walls, dining trays and rows of vases were placed around rooms and pools. For further information about ‘flowers in baskets or vases’ motifs please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, pp. 110-111.

The tulip has a symbolic meaning in Ottoman art. The letters of the word tulip (Lâle [ هللا]) in Turkish and Persian are the same letters used for writing the word Allah [ اللَّه] (God). These two words have the same numerological value in the abjad system (a decimal alphabetic numeral system in which the twenty-eight letters of the Arabic alphabet are assigned numerical values). Tulip is one of the leading decorative elements in Ottoman art; frequently used together with roses, hyacinths, saz leaves. It is also used with khatai blossoms as can be seen in the present tile. Tulip also played a role in imagery

in Ottoman poetry. In many poems, tulip leaves are likened to the cheeks of the beloved. The word lāleh-khad (lâle-had), often used in Ottoman poetry, means ‘tulip-cheeked’. Tulips were among the most favoured motifs used in the Ottoman court workshops in the 16th century. The name ‘tulip’ is thought to have derived from the Turkish word tülbend (from the Persian word دنبلد [dulband]) -meaning ‘large cotton band which is used in the making of turban or headgear’- because of the fancied resemblance of the flower to a turban.

An almost identical Iznik tile is in the Sadberk Hanım Museum (Inv. No. 4184), Istanbul. Please see, the exhibition catalogue Istanbul: The City and the Sultan, December 16, 2006 - April 15, 2007, organised by Stichting Projecten De Nieuwe Kerk, Amsterdam, 2006, p. 52.

Provenance: Ex-Doltrap Family Collection, The Netherlands.

Mesopotamia

9th Century

Diameter: 20.5 cm.

Height: 6 cm.

Earthenware, the rounded earthenware body covered with an opaque white glaze, Arabic inscription painted in glaze in cobalt blue from right rim towards the centre.

This bowl is an exceptional example of early Islamic tinglazed pottery and epitomises the powerful abstraction of the early Abbasid style. While the shape follows a Chinese prototype, the use of cobalt blue is a novel departure that was to have a profound and long-lasting influence on future ceramics. The application of cobalt directly into the raw glaze creates a soft impression, described by Arthur Lane as “like ink on snow”. Arthur Lane, Early Islamic Pottery, London, 1947, p. 13.

Inscription in Arabic, in kufic script:

هلمع هلمع

Translation:

“What was made, was made.”

An Abbasid bowl bearing the same kufic inscription is published in Oya Pancaroğlu, Perpetual Glory –Medieval Islamic Ceramics from the Harvey B. Plotnick Collection, The Art Institute of Chicago, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2007, p. 40 (Catalogue No. 1).

Calligraphy has at all times been one of the major ‘motifs’ of Islamic art and continues to be a primary element of Islamic design both in the formal sense and as means of communication. Calligraphy, as a motif, served both visually with its uniquely Islamic aesthetic and delivered messages as a text; such as good wishes to the owner, poems or pious quotations like verses from the Qur’an or sayings of the Prophet Muhammad. In many instances, calligraphic inscriptions, particularly verses from the Qur’an or sayings of the Prophet, are considered as a source of grace and blessing (barakah) as well. In some rare cases, the inscription records the

date which allow us to know the piece’s exact date of production. For further information on the use of calligraphy on early Islamic ceramics please see Ernst Grube, Islamic Pottery of the Eighth to the Fifteenth Century in the Keir Collection, Faber & Faber, London, 1976, p. 98.

There is a comparable Abbasid opaque white glazed bowl with a similar kufic inscription in cobalt blue in the Khalili Collection (Accession No. POT184), London. Please see, Ernst Grube, Cobalt and Lustre, The Nour Foundation, Ed. Julian Raby, Azimuth Editions, Oxford University Press, 1994, p. 45, no. 34. The inscription on the Khalili bowl has been deciphered as ‘Abduhu ‘Abduhu (His [God’s] slave). For more information about such inscriptions on early Islamic pottery please see, Manijeh Bayani, “A Note on the Content and Style of Inscriptions” in Oya Pancaroğlu, Perpetual Glory –Medieval Islamic Ceramics from the Harvey B. Plotnick Collection, The Art Institute of Chicago, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2007, pp. 154-155.

Provenance: Private UK Collection

Persia

Early 13th Century

Diameter: 22 cm.

Height: 9.5 cm.

Fritware, of shallow form with flaring walls and flattened rim on a low foot, decorated in two shades of underglaze cobalt blue with black under a transparent colourless glaze, with six black ribbon bands radiating outwards from the centre, each with a line of cursive script, the interstices with large palmette motifs formed from split-leaves issuing upwards towards the rim, the back with sprays of waterweed.

The inscriptions written in six lines, in white, on black bands, are selected verses from classical Arab poetry. They are about the importance of learning and the value of knowledge.

The first four lines are from a poem from the Diwan (collected works) of the famous al-Imam al-Shafi (d. 820 C.E. Please see, Diwan al-Imam al-Shafi, ed. Abd al-Rahman al-Mustawi, Dar al-Ma‘rifat, Beirut, 1426 A.H. / 2005 C.E., p. 94).

Translation

“The days will reveal to you that of which you are ignorant, The one whom you did not provide provisions will bring you news.”

Early 13th century Kashan ceramics are inscribed both in Arabic and Persian. Very few pieces contain only Arabic text. For more information please see, Manijeh Bayani, “A Note on the Content and Style of Inscriptions” in Oya Pancaroğlu, Perpetual Glory – Medieval Islamic Ceramics from the Harvey B. Plotnick Collection, The Art Institute of Chicago, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2007, p. 154.

Translation

“Learn, no one is born learned and erudite.

And a brother of knowledge is not like someone who is ignorant. The leader of people who has no knowledge, Becomes a little man if people turn against him.”

The following two lines are from the Diwan of Tarafah ibn al-‘Abd (d. 569). Tarafah is one of the celebrated seven poets (Tarafah ibn al-‘Abd, AlNabigha, Antarah b. Shaddad, Zuhayr b. Abi Sulma, ‘Alqama and Imru al-Qays) of the most celebrated anthology of ancient Arab poetry, the Mu‘allaqat.

Calligraphy has at all times been one of the major ‘motifs’ of Islamic art and continues to be a primary element of Islamic design both in the formal sense and as means of communication. Calligraphy, as a motif, served both visually with its uniquely Islamic aesthetic and delivered messages as a text; such as good wishes to the owner, poems or pious quotations like verses from the Qur’an or sayings of the Prophet Muhammad. In many instances, calligraphic inscriptions, particularly verses from the Qur’an or sayings of the Prophet, are considered as a source of grace and blessing (barakah) as well. In some rare cases, the inscription records the date which allow us to know the piece’s exact date of production. For further information on the use of calligraphy on early Islamic ceramics please see Ernst Grube, Islamic Pottery of the Eighth to the Fifteenth Century in the Keir Collection, Faber & Faber, London, 1976, p. 98.

A comparable Kashan bowl, with similar decoration and inscriptions, is in the Sarikhani Collection. Please see, Oliver Watson, Ceramics of Iran – Islamic Pottery from the Sarikhani Collection, Yale University Press, London, 2020, p. 301, no. 152. A second very similar Kashan bowl is in the Metropolitan Museum (Acc. No. 20.120.37), New York. Please see the link, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/ collection/search/447151

Provenance: Ex-Matossian Collection

Timurid Empire 15th Century

Diameter: 34 cm.

Height: 10 cm.

Painted in black under a pale turquoise glaze, decorated with a pineapple, floral elements, and an incised pattern of spirals.

This striking turquoise and black bowl belongs to a group of Persian ceramics known as the Kubachi-ware. Kubachi is the name of a town in the Caucasus where examples of this pottery were discovered. As for their centre of production, art-historians have come to the conclusion that Kubachi ceramics were produced in north-western Persia.

Kubachi-ware is made of fritware. Some examples, like the present bowl, feature the graceful combination of turquoise glazes with black figures. This aesthetic appears to be a response to Chinese celadon.

The floral elements on the present piece played an important role in Persian art since flowers were regarded as blessed reminders of the gardens of heaven. In Persian poetry, the rose symbolizes the beloved, hyacinth the beloved’s hair, daffodil the beloved’s eyes, tulip the beloved’s cheeks, jasmine the beloved’s skin. Foreign travellers and ambassadors who visited Persia frequently remarked about this love of flowers. For further information and discussion about the use of floral motifs please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, pp. 174-178.

A very similar Kubachi bowl is in the Metropolitan Museum (Acc. No. 17.120.70), New York. Please see the link, https://www.metmuseum.org/ art/collection/search/446926 In the Metropolitan Museum’s entry, it has been stated that “This bowl is among the earliest examples” of Kubachi-ware.

Provenance: Private UK Collection

Persia

Early 13th Century

Height: 21.3 cm.

Cylindrical with slightly flaring sides, upward sloping shoulder, short truncated neck and out-turned rim. The body decorated with a frieze of bold kufic inscription against scrolls, either side naskh inscriptions scratched through a solid band running around the albarello. The shoulder with the frieze of floral scrolls. Another band of scratched naskh inscription around the neck. The mouth with a solid band of lustre, stylized leaves around the base.

Arabic inscriptions repeated in naskh bands read:

Transliteration:

‘Al-iqbāl wa al-dawla wa al-in‘ām’

Translation:

‘Good-fortune and prosperity and blessings’.

Calligraphy has at all times been one of the major ‘motifs’ of Islamic art and continues to be a primary element of Islamic design both in the formal sense and as means of communication. Calligraphy, as a motif, served both visually with its uniquely Islamic aesthetic and delivered messages as a text; such as good wishes to the owner, poems or pious quotations like verses from the Qur’an or sayings of the Prophet Muhammad. In many instances, calligraphic inscriptions, particularly verses from the Qur’an or sayings of the Prophet, are considered as a source of grace and blessing (barakah) as well. In some rare cases, the inscription records the date which allow us to know the piece’s exact date of production. For further information on the use of calligraphy on early Islamic ceramics please see Ernst Grube, Islamic Pottery of the Eighth to the Fifteenth Century in the Keir Collection, Faber & Faber, London, 1976, p. 98.

In the early days of the 20th century, medieval Persian lusterware survived only in fragmentary form. This all changed in the 1940s with the discovery of large storage jars containing lustre-painted ceramics in near perfect condition (similar to the present jar), in the medieval city of Gurgan, near modern Gunbad-i Qabus in the Caspian region of Iran, please see Oya Pancaroğlu’s Perpetual Glory: Medieval

Islamic Ceramics from the Harvey B. Plotnick Collection, The Art Institute of Chicago, 2007, p. 124. These finds were written up and published after the excavations by Dr. Mehdi Bahrami, Gurgan Faiences, Cairo, 1949.

Lustre technique, invented by Muslim masters in the 9th century, is an over-glaze technique, in which the pigment is applied a second firing at a lower temperature than the first and is applied to the surface of a hard, fired glaze.

A certain Abu’l Qasim, brother of Yusuf of the Abu’l Tahir family which dominated lustre production in Kashan, wrote on pottery in 1300. Abu’l Qasim ended up as a court historian at the Mongol capital Tabriz, where amongst other works he contributed to the monumental Jāmi‘ al-Tawārikh (Compilation of Histories) under the direction of the Mongol vizier Rashid-al-Din. At the end of a work on precious stones and perfumes, Abu’l Qasim added an appendix on the art of pottery, which he described as a ‘kind of alchemy’. Please see Oliver Watson’s Persian Lustre Ware, Faber and Faber, London, 1985, pp. 31-32.

Lustre reached its apogee in the early 1200s, the time this albarello was produced, just before the devastating Mongol invasions which happened twenty years later.

Provenance: Private UK Collection

Ottoman Empire

18th Century

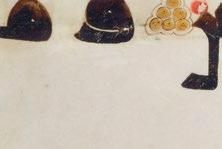

Heights: 9 cm., 9 cm., 8 cm.

Total Height: 35 cm.

Of oval form, three ceramic hanging ornaments with green, blue, yellow and brown underglaze painting, decorated with crosses and seraphim.

The Christian association of these Kütahya eggs is clearly indicated by the crosses and seraph motifs. A seraph (plural seraphim) is a heavenly figure which plays a role in Judaism, Christianity and Islam. In Christian tradition, seraphim are placed in the highest rank in the angelic hierarchy. They are the caretakers of God’s throne. Christian theology developed an idea of seraphim as beings of pure light who enjoy direct communication with God.

Similar Kütahya ceramic hanging ornaments, in egg form, can be seen hanged above the altar in the Church of the Holy Archangel in Jerusalem. Please see the photograph in John Carswell, Kütahya Tiles and Pottery from the Armenian Cathedral of St. James, Jerusalem, Volume II, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1972, Plate 24. For other comparable examples in the Armenian Catholic San Lazzaro monastery in Venice please see, ibid, p. 68 (Fig. 25 o, q). Similar objects are also found in Iznik ware and were destined for mosques. Nurhan Atasoy & Julian Raby. Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, Thames & Hudson, London, 1989, p.41.

These eggs appear to have combined different functions and symbolic meanings. They were symbols of fertility associated with the egg. They were souvenirs of the pilgrimage (similar to ostrich eggs that were brought back from Mecca). Practically, they appear to have been used, in the suspension of oil lamps, to prevent rodents climbing down the chains to consume the oil. Oliver Watson, Ceramics from Islamic Lands – Kuwait National Museum – The Al-Sabah Collection, Thames & Hudson, London, 2004, p. 447.

Two comparable Kütahya ceramic hanging ornaments, decorated with seraphim, from the Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation Collection, Istanbul, are published in Garo Kürkman’s Toprak, Ateş ve Sır – Tarihsel Gelişimi, Atölyeleri ve Ustalarıyla Kütahya Çini ve Seramikleri, Suna ve İnan Kıraç Vakfı, Istanbul, 2005, pp. 162, 163, 165. For other examples please also see the exhibition catalogue, Aspects of Armenian Art: The Kalfayan Collection, Athens, 2010,

p. 73, Nos. 20, 21, 22 and Oliver Watson, Ceramics from Islamic Lands – Kuwait National Museum –The Al-Sabah Collection, Thames & Hudson, London, 2004, p. 447.

Provenance:

Ex-Dr. Oliver Impey (1936-2005), and Dr. Jane (Mellanby) Impey (1938-2021) Collection, Oxford.

Dr. Oliver Impey was a renowned authority on Japanese art, senior assistant keeper and curator of the Japanese collections in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. He was educated at Eton and Oxford, where he took his BA in Zoology. His doctoral thesis (which is to be published posthumously) was on the workings of lizards’ jaws. As an Orientalist, connoisseur and naturalist, he had heredity on his side. Generations of Impeys had served in India, going back to Sir Elijah Impey, Chief Justice of Bengal in the 1770s. He and his wife Mary were important collectors and patrons of Indian painting. Lady Impey, in particular, assembled a large menagerie of Indian birds and beasts and had them superbly depicted, often in life size, by her Indian artists. Returning to Oxford, he rejoined the Zoology department and, with customary energy, finished writing his thesis after he had started work at Sotheby’s. In Sotheby’s Furniture and Textiles Department, Oliver’s instinctive connoisseurship and remarkable breadth of knowledge began to develop fully, as well as his intimate knowledge of the art trade. Oxford, however, reclaimed him two years later. In 1967 he was appointed Assistant Keeper for Japanese Art at the Ashmolean. It was Oliver, with Arthur MacGregor, who organised the major international conference on ‘The Origins of Museums’ for the Ashmolean’s Tercentenary in 1983. This gave rise not only to a classic volume of scholarly papers but the founding of the learned Journal of the History of Collections, which they co-edited. In the early 1980s he published ground-breaking articles on seventeenthcentury Japanese export lacquer and on early Japanese painting. In 1996 his most important contribution to Japanese ceramic studies appeared, the masterly Early Porcelain Kilns of Arita. The exceptional esteem in which ‘Impey-san’ was held in Japan for his scholarly contribution was marked in 1997 by the award of the prestigious Koyama Fujio Memorial Prize and Medal. This was followed soon after by the award of his Oxford DLitt. He passed away in 2005.

Dimensions: 22.5 x 16 cm

Fritware, moulded, underglaze polychrome painted tile, depicting a prince riding a horse, holding his falcon with his left hand. The background of the tile has been embellished with spring flowers and palaces in far distance. The top decorated with a band of birds resting on intertwined vines.

The tradition of depicting people and animals has always been alive for centuries in regions where the Muslim faith spread. The tradition of depicting people and animals has deep roots in Seljuk, Fatimid, Ayyubid, early Mamluk art, Ottoman, Mughal, Safavid and Qajar art. Figures were not just used for a decorative purpose but also to convey religious, cultural and political messages. The most frequent themes are a ruler seated on a throne as a symbol of sovereignty; battle scenes, scenes of palace life showing activities such as shooting with a bow and arrow on horseback, hunting with hawks/falcons, playing polo, figures of musicians, dancers, servants offering wine in a cup which represent palace entertainments. The present tile can be interpreted under this category. For further information please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanim Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanim Museum, Istanbul, 2020, pp. 146-147.

Falconry is the hunting of wild animals in their natural state and habitat by means of a trained falcon. The falcon was a symbolic bird of the ancient Mongol tribes. In the 7th century, concrete figures of falconers on horseback were described on the rocks in Kyrgyz. Falconry was probably introduced to Europe around 400 C.E., when the Huns and the Alans invaded from the east. Historically, falconry was a popular sport and status symbol among the nobles of medieval Europe and the Islamic world.

A comparable Qajar tile with an equestrian with a falcon is in the National Museums, Scotland. Please see the article, Friederike Voigt, “Equestrian Tiles and the Rediscovery of Underglaze Painting in Qajar Iran”, Revealing the Unseen: New Perspectives on Qajar Art, Edited by Gwenaëlle Fellinger & Melanie Gibson, Gingko – Louvre Editions, Paris, 2021, p. 159.

Qajar Empire

Attributable to the Artist

ʻAhmadʼ (Active between 1815-1850).

First Half of the 19th Century

Dimensions: 151.5 x 86 cm.

Oil on canvas, depicting a Persian noble lady, possibly a member of the Qajar imperial harem, as an acrobat performing a handstand, wearing a lavish costume embroidered with roses and decorated with pearls.

There are two closely related Qajar acrobat portraits in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (Accession numbers: 719-1876 and 720-1876), both attributed to the artist ‘Ahmad’ by Layla S. Diba. Please see the related entry in the exhibition catalogue, Royal Persian Paintings – The Qajar Epoch 1785-1925, Edited by Layla S. Diba and Maryam Ekhtiar, I. B. Tauris Publishers in Association with Brooklyn Museum of Art, 1998, New York, pp. 210-211, Nos. 60, 61.

The present portrait is almost identical to the second V&A portrait (Accession number: 720-1876, Dimensions: 151.5 x 80.4 cm.) which -according to the online museum entry- was “part of a group purchased by the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1876. At the time it was described as being ‘From the Shah’s palace at Tehran’. The painting may well have been removed from a palace erected by Fath ‘Ali Shah (r. 1797-1834). His residences were often decorated with series of oil paintings in this style. … Many of the series painted for Fath ‘Ali Shah show imaginary portraits of members of the royal harem.”. For the complete entry please see, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O69980/femaletumbler-oil-painting-unknown/

Layla S. Diba has identified the origin of the V&A Qajar acrobat portraits as the Gulistan Palace, Tehran, “according to a letter dated October 1875 from Colonel R. Murdoch Smith, of the Telegraph Department, Tehran”. Please see, Ibid, p. 210.

The lady’s costume embroidered with intertwined roses tell us a story. In Persian poetry, the rose symbolizes ‘the beloved’ whose love makes the nightingale, ‘the lover’, sing the most beautiful love songs. Please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk

Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, p. 94. The worldfamous 14th century Persian poet Hafez-i Shirazi, in the following lines, likens his beloved to a rose and himself to a nightingale: “I went to the garden one morning to pick a rose and suddenly heard a nightingale’s song. Like me, the poor bird had fallen in love with a rose and in the field, raised a commotion with his cries.”

The exquisite roses on our lady’s costume therefore allow us to identify her as the beloved, perhaps one of the favourites of the shah.

The painting also shows how ‘liberal’ and ‘modern’ 19th century Persian women were. In those days, the social and political atmosphere obviously allowed a Persian noble lady, in this case probably a member of the imperial harem, to be depicted in a painting as an acrobat-dancer. The painting belongs to a small group of full-length portraits associated with Fath ‘Ali Shah’s (r. 1797-1834) patronage, some of which are reported to have come from the Gulistan Palace in Tehran.

A comparable Qajar acrobat in the ‘Archives Cantonales du Tessin’ is published in the exhibition catalogue L’Empire des Roses: Chefs-d’œuvre de l’Art Persan du XIXe Siècle, Snoeck, Louvre Lens, Paris, 2018, no. 191, p. 181.

A similar portrait of a Qajar a female acrobat performing handstands was sold at Christie’s London. Please see, Christie’s - Art of the Islamic and Indian Worlds including Oriental Rugs and Carpets, 11 April 2000, Lot 111.

Provenance: Ex-Private French Collection from Corbeil Essonne.

“I went to the garden one morning to pick a rose and suddenly heard a nightingale’s song. Like me, the poor bird had fallen in love with a rose and in the field, raised a commotion with his cries.”

Hafez-i Shirazi (d. 1390)

Ottoman Empire 18th-19th Century

Height: 12cm.

Of bulbous form of low footring with screw-fitted narrow cylindrical neck, decorated with polychrome enamels depicting spring flowers between foliate gilt bands.

Enamelled objects such as bowls, covered dishes, rosewater sprinklers, mastic-holders were increasingly fashionable among the Ottoman elite. Especially during the 18th and 19th centuries, these objects played an important role in the daily lives of the members of the Ottoman upper classes both with their practical uses and decorative values. This is a rare, miniature rosewater sprinkler, probably produced for a lady.

The spring flowers decorating the present piece have an important place in the Ottoman decoratif repertoire. In the Ottoman period flowers were a constant part of daily life, grown in gardens everywhere, from palaces to humble homes. Flowers were blessed reminders of the gardens of heaven. Foreign travellers and ambassadors who visited the empire frequently remarked about this love of flowers. The 17th century Ottoman writer and traveller Evliya Çelebi describes how vases of roses, tulips, hyacinths, narcissi and lilies were placed between the rows of worshippers in the Eski Mosque and the Üç Şerefeli Mosque in Edirne, and how their scent filled the prayer halls. As depicted in the present rosewater sprinkler, vases of flowers adorned niches in the walls, dining trays and rows of vases were placed around rooms and pools. For further information please see, (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, pp. 86-90.

Provenance:

Ex-Argine Benaki Salvago Collection.

Argine Benaki Salvago (1883-1972)

Argine Benaki Salvago was one of the leading social and cultural figures of Alexandria in the 1930s. Thanks to its position as the main trading port in the southern Mediterranean, in those years Alexandria was a cosmopolitan hub. The expansion of commercial traffic through the ancient port in the late Ottoman period offered an opportunity for entrepreneurial Greek families in the city, such as the Benakis, Choremis and Salvagos, to thrive economically. Argine’s parents, Emmanuel

Benaki and Virginia Choremi, were both leading cotton producers, whose marriage sealed their business alliance, transforming them into the primary exporters of high-quality Egyptian cotton. Her husband, Michael Salvago, also a cotton baron, came from a family whose many notable achievements included the setting up of the National Bank of Egypt in 1898. Against this backdrop of private wealth, urbane cosmopolitanism and international sophistication, it is no surprise that prestigious collections of art were formed at this time.

In 1927, Argine’s brother Antony left Alexandria for Athens, where four years later the lion’s share of his collection, as well as the family’s home in Athens, was donated to the Greek state with the foundation of the Benaki Museum. The legacy of this great collecting dynasty was therefore preserved in a public institution to be enjoyed and appreciated by the general public. Argine also went on to donate her extensive collection of Persian antique jewellery, which can be viewed today in the Benaki Museum of Islamic Art.

Signed Ahmad, Dated 1261 A.H. 1844 C.E.

Length: 42.2 cm.

Width: 4.5 cm.

Dagger with curved steel blade, and scabbard. Hilt with red cabochon tourmalaine finial, hilt and scabbard decorated with polychrome enamel decoration, with spring blossoms, and green leaves with gilt copper borders.

Enamelled hilts and scabbards of this type have been produced throughout the second half of the 18th and first half of the 19th centuries across the Middle East. Similarly decorated enamelled daggers have been catalogued both as from the Ottoman and the Qajar empires. A similar example, catalogued as Qajar, is in the British Museum. Please the link, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/ object/W_1878-1230-903

On the other hand, a closely related enamelled dagger and scabbard (Accession No. JLY 1748), also signed ‘Ahmad’, dated 1231 A.H. (1815 C.E.), in the D. Nasser Khalili Collection, London, is catalogued as Ottoman. Please see, David Alexander, The Arts of War – Arms and Armour of the 7th to 19th Centuries, The Nour Foundation, Azimuth Editions and Oxford University Press, London, 1992, no. 87, pp. 146-147.

The artist’s signature ‘Ahmad’ on the Khalili dagger is identical with the signature on the present dagger. Our dagger, therefore, appears to have been produced by the same artist who produced the Khalili dagger.

Spring flowers and blossoms, decorating the present piece, are much favoured motifs widely used in Ottoman art. In Ottoman culture, flowers were a constant part of daily life, grown in gardens everywhere, from palaces to humble homes. Flowers were blessed reminders of the gardens of heaven. Foreign travellers and ambassadors who visited the Ottoman Empire frequently remarked about this love of flowers. For further information please see, Motif from the Sadberk Hanım Museum Collection (written by Turgut Saner, Şebnem Eryavuz and Hülya Bilgi), Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, 2020, pp. 86-90.

A comparable Ottoman incense-burner, very similarly decorated with enamel, was sold at Christie’s, London. Please see, Christie’s - Art of the Islamic and Indian Worlds including Oriental Rugs and Carpets, 26 October 2017, Lot 207.

Provenance:

Ex-Private South Carolina Collection

Heigth: (The Ornament)

16.8 cm.

Heigth: (The Ornament with the Tassel) 59 cm.

The eight-ribbed cantaloupe-melon-form ornament, set with peridots and carnelians, mostly cabochon, in the contours, at the base a large rock crystal bead emanating a thread tassel.

Peridots, decorating the present hanging ornament, were mined in Egypt (on the island of Zabarjad in the Red Sea) throughout the Ottoman period and the treasury of the Topkapı Palace still contains large numbers of polished but unset peridots. Carnelians, much favoured in Islamic jewellery, were mostly mined in India.

Hanging ornaments, similar to the present one, decorated with precious and semi-precious stones -such as peridots and carnelians- were used for decorating mosque interiors and as throne-ornaments. The historians relate that from the earliest centuries of Islam it was the custom of rulers to send valuable ornaments to be hung at the Ka’bah in Mecca and in the Tomb of the Prophet at Medina. Traditionally hanging ornaments were suspended from the dome in mosques because the dome symbolized the sky, and the hanging ornaments, sparkling with peridots and carnelians, symbolized the stars. In this symbolism, there is a direct reference to the Qur’an [24:35]: “Allah is the light of the heavens and the earth. His light may be likened to a niche wherein is a lamp, and the lamp is in the crystal which shines in starlike brilliance.”

)

As a characteristic feature in these hanging ornaments, a rock crystal bead emanating a thread tassel, as in the present piece, is a direct reminder of the words of this Qur’anic verse [24:35]: “… in the crystal which shines in star-like brilliance” (

)

Comparable hanging ornaments in the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul, are published in Nazan Ölçer et al, Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Akbank, Istanbul, 2002, pp. 298, 299. According to the museum’s register, two of these ornaments, similar to the present piece in form and decoration, were brought to the museum from the Laleli Mosque in Istanbul. Please see, ibid, 2002, p. 298.

Two imperial Ottoman hanging ornaments, made for the Mosque of Prophet Muhammad (Masjid al-Nabavi) in Medina, have survived. The first, decorated with a large emerald, commissioned by the Ottoman sultan Mustafa III (r. 1757-1774), is in the Topkapı Palace Museum (inv. no. 2/7618). Please see the exhibition catalogue, Topkapı Palace: The Imperial Treasury, MAS, Istanbul, 2001, p. 46. The second one, decorated with three emeralds, also made for the Mosque of Prophet Muhammad (Masjid al-Nabavi) in Medina, commissioned by Sultan Abdulhamid I (r. 1774-1789), is in the Topkapı Palace Museum (inv. no. 2/7617). Please see ibid, 2001, p. 52.

Hanging ornaments continued to be produced in various forms. Some comparable examples were used for decorating thrones. There are certain similarities in decoration which indicate a relation between hanging

Hanging ornament in the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul, (Inv no. 188), brought to the museum from the Laleli Mosque in Istanbul, After Nazan Ölçer et al, Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Akbank, Istanbul, 2002, p. 298.

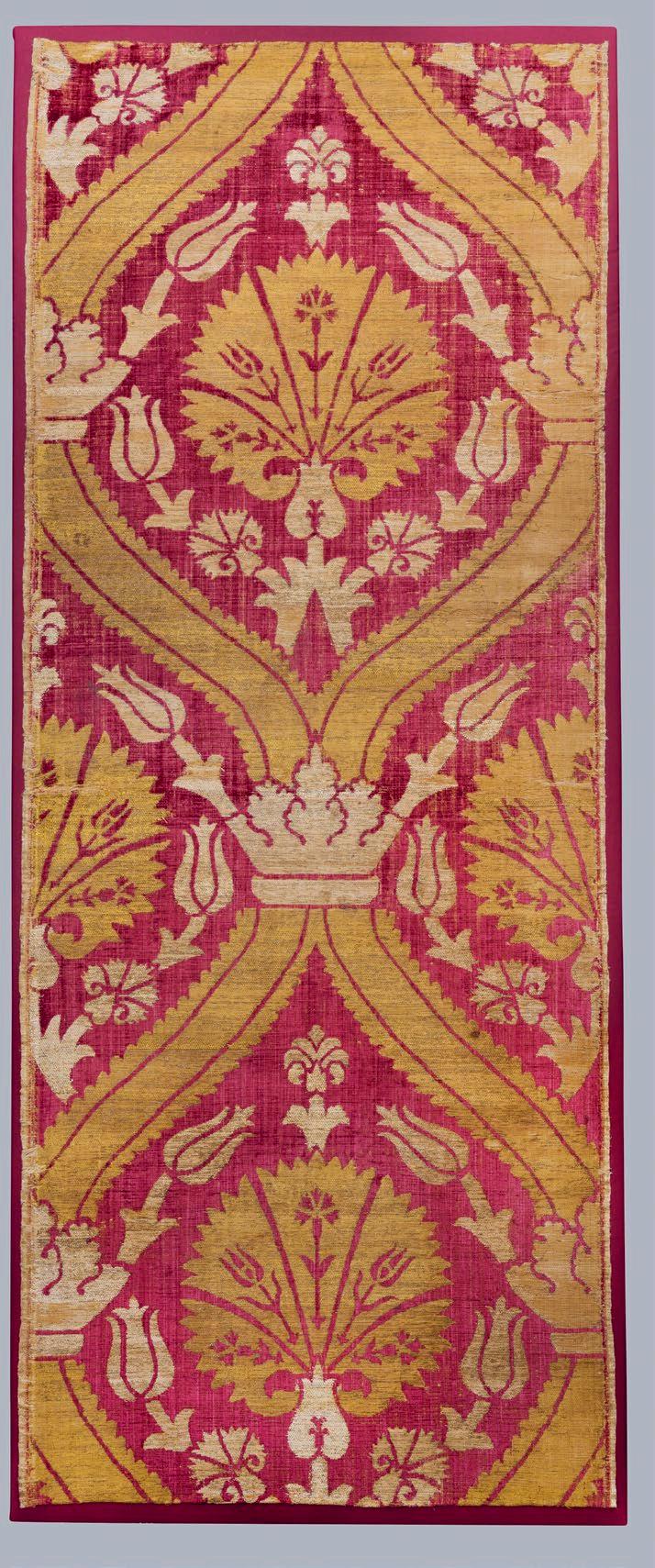

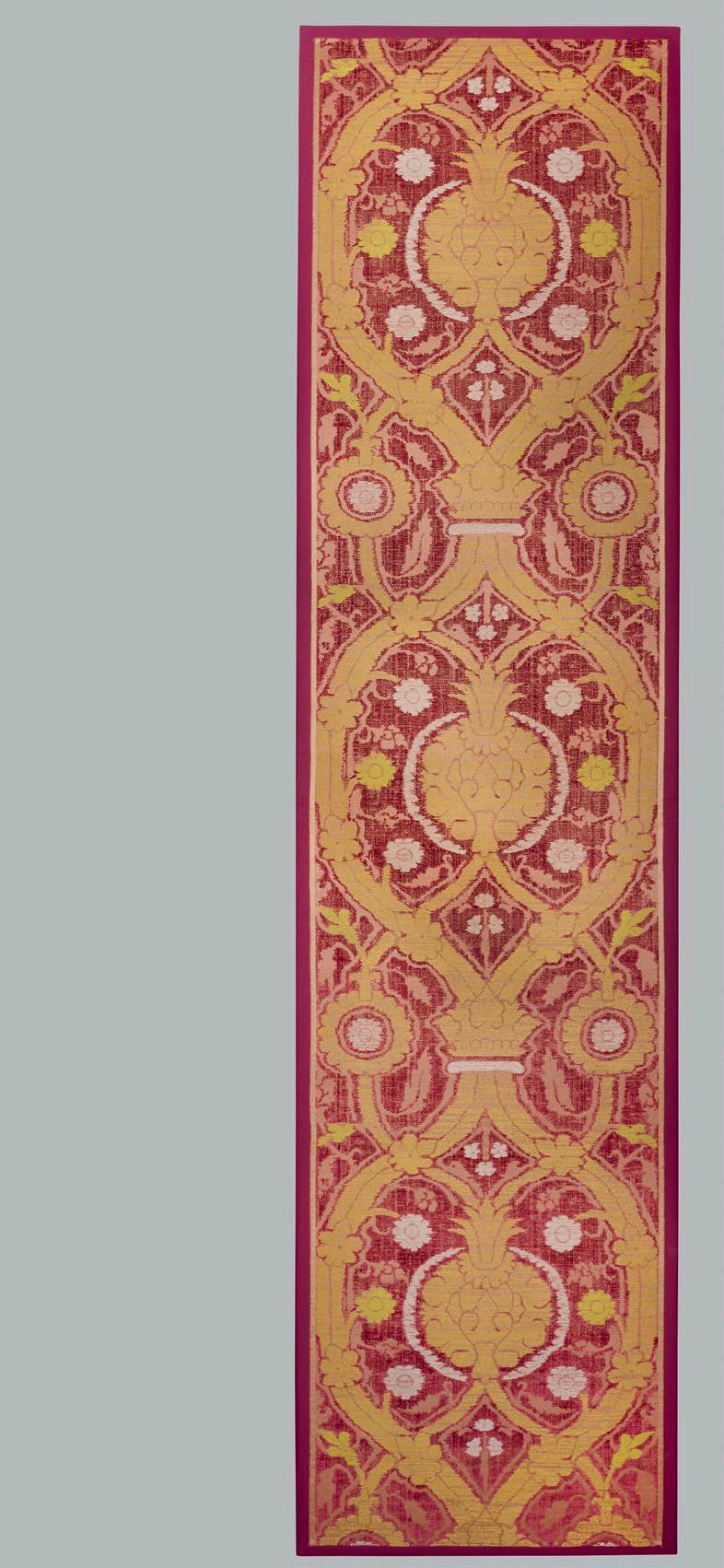

Hanging ornaments above Sultan Ahmed III’s (r. 1703-1730) throne. After the exhibition catalogue, Lale Devrinin bir Görgü Tanığı Jean-Baptiste Vanmour, texts written by Eveline Sint Nicolaes et al, Koçbank, Istanbul, 2003, p. 195.