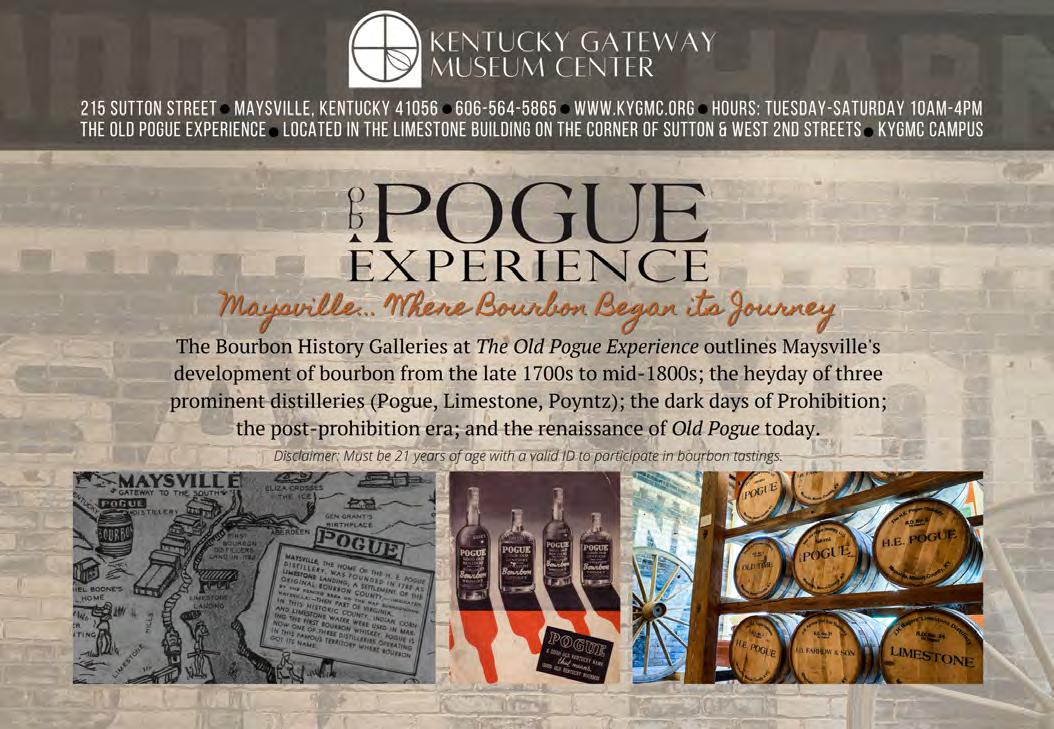

www.kentuckymonthly.com DISPLAY UNTIL 03/14/2023 FEBRUARY 2023 with Kentucky Explorer and more... Moonlight Schools Lee “Mr. Western” Robertson ADA The Literary Issue LIMÓN UNITED STATES POET LAUREATE 2023 Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame Inductees Penned Literary Contest Winners

Book your getaway at parks.ky.gov!

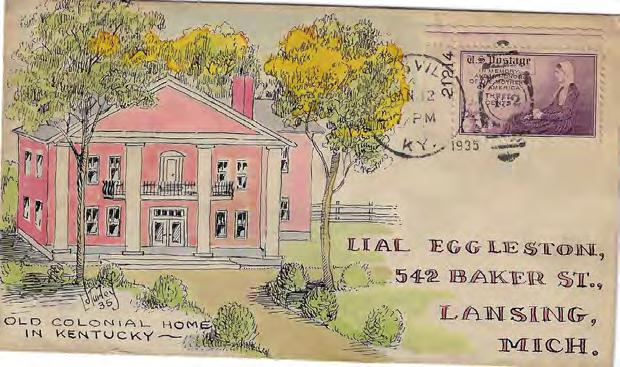

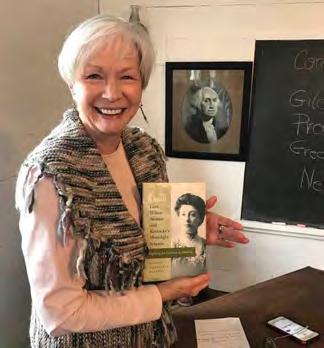

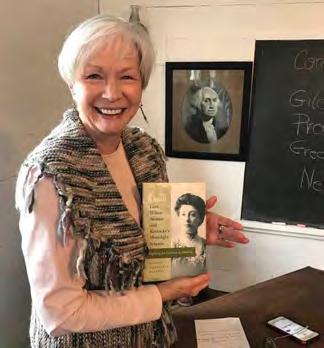

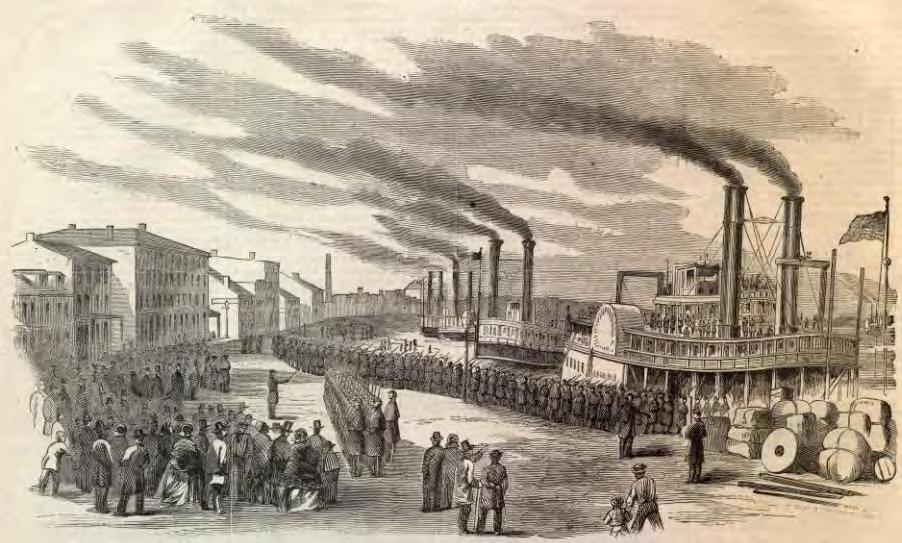

36 The Gift of Literacy Cora Wilson Stewart’s Moonlight School concept opened the world of reading to thousands of Kentuckians

40 Mr. Western After more than six decades, Lee Robertson remains a beloved and valued supporter of Western Kentucky University

DEPARTMENTS 2 Kentucky Kwiz 3 Readers Write 4 Mag on the Move 6 Across Kentucky 8 Cooking 49 Kentucky Explorer 60 Past Tense/ Present Tense 61 Off the Shelf 62 Field Notes 63 Calendar 64 Vested Interest 12 Poet for the People

Limón of Lexington wants to connect through her writing, her podcast and her post as the U.S. Poet Laureate 16 2023 Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame Inductees Five of the Commonwealth’s most talented and accomplished writers join the distinguished group 26 Penned: The 15th Annual Writer’s Showcase The best of reader-submitted fiction, creative nonfiction and poetry

Ada

kentuckymonthly.com 1 in this issue 12 ON THE

8 FEBRUARY

COVER

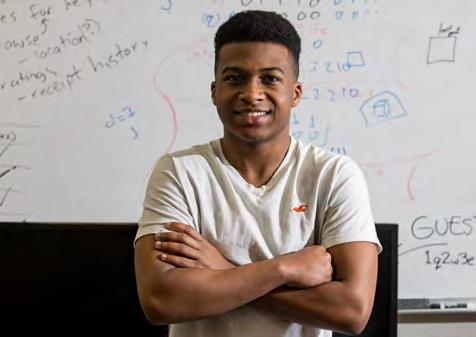

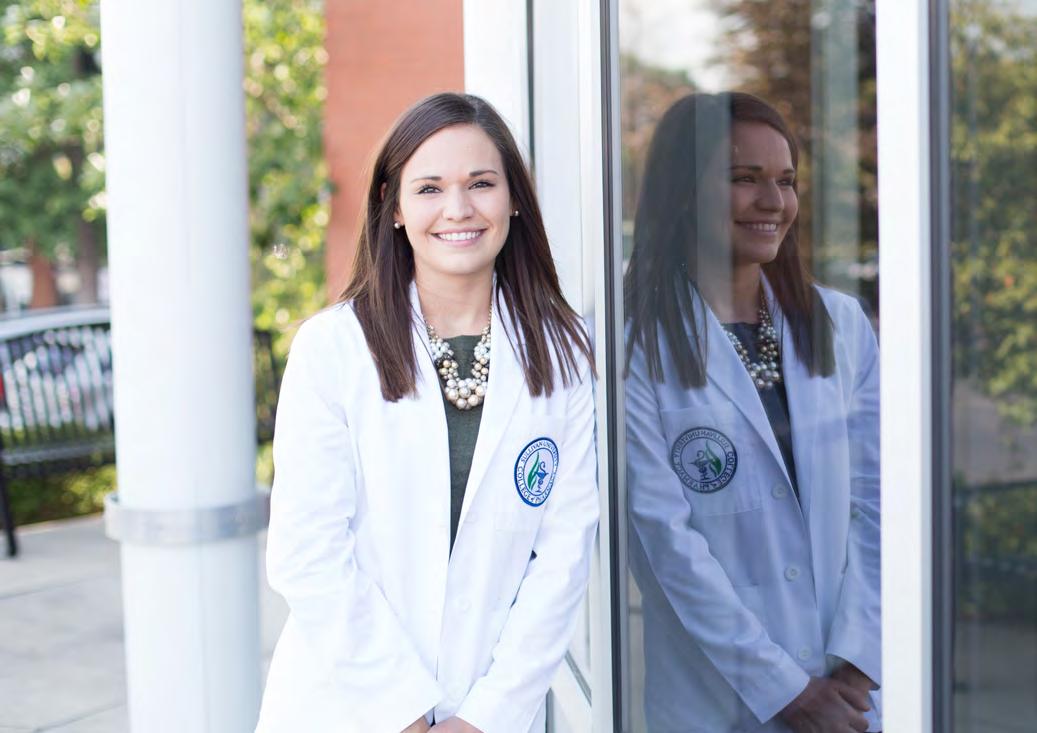

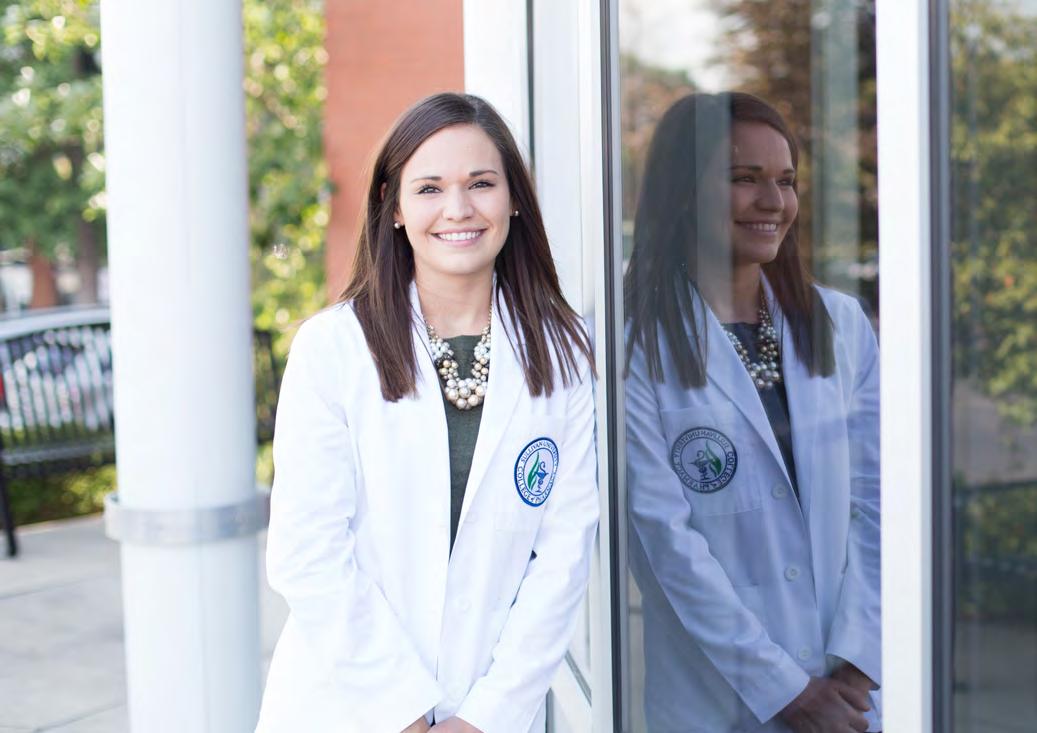

United States Poet Laureate Ada Limón; Lucas Marquardt photo

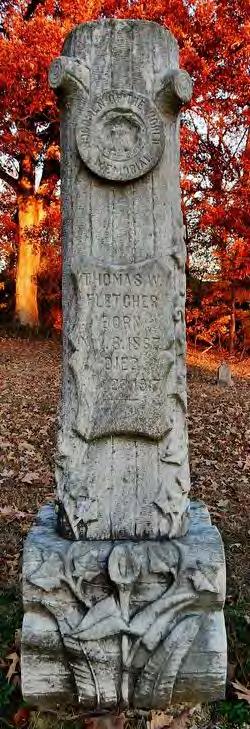

This issue is dedicated to the memory of the Thomas L. Hall (1944-2023), founding boardmember of Kentucky Monthly and an editor for BloodHorse.

kentucky kwiz

Test your knowledge of our beloved Commonwealth. To find out how you fared, see the bottom of Vested Interest.

1. In 2002, Nicholas Countians William B. and Claudia Lillian Jackson Ritchie were recognized by Guinness World Records as the world’s oldest living married couple. The 83-year, 231-day marriage ended November 22 of that year for what reason?

A. A nasty and bitter divorce

B. William’s passing

C. Claudia’s passing

2. While Dean and Carl Burton of Hartford have 11 years to tie the Ritchies’ record, Mrs. Burton said the secret to a long marriage is “making sure to love each other” and …

A. “a little hug and a little kiss helps it along”

B. “don’t threaten to throw away his baseball cards”

C. “don’t invite your four elderly aunts to move in indefinitely”

3. This best-selling romance writer’s career began in 1973, when she received $100 for a funny anecdote she submitted to Reader’s Digest. Name her.

A. Karen Robards

B. Tina D.C. Hayes

C. Mysti Parker

4. The 2017 Hallmark movie Runaway Romance was filmed in which cities?

A. Owensboro, Philpot and Utica

B. Hartford, Beaver Dam and Dundee

C. Glasgow, Horse Cave, Cave City and Munfordville

5. The unincorporated community of Love is located in which county?

A. Fulton

B. Butler

C. McLean

6. There is no waiting period for marriages in Kentucky, but you must pay a $50 fee for the license, and it expires in how many days?

A. 7

B. 30

C. 365

7. While a 50-guest wedding reception at the Embassy Suites by Hilton in Lexington will cost $10,066, the least expensive— other than your own backyard— can be found where?

A. Smothers Park in Owensboro

B. The Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville

C. Lost River Cave in Bowling Green

8. How many times can you marry the same man in Kentucky?

A. Two

B. Three

C. Four

9. What are Kentucky Sweethearts?

A. A toffee and caramel covered cherry

B. A Bluegrass band from Prestonsburg

C. The University of Kentucky’s majorette squad

10. Few things are more comforting than a hug. Which bourbon maker recently unrolled a line of clothing to capitalize on that feeling?

A. Jim Beam Distillery in Clermont

B. Buffalo Trace Distillery in Frankfort

Celebrating the best of our Commonwealth

© 2023, Vested Interest Publications

Volume Twenty-Six, Issue 1, Febuary 2023

Stephen M. Vest

Publisher + Editor-in-Chief

Editorial

Patricia Ranft Associate Editor

Rebecca Redding Creative Director

Deborah Kohl Kremer Assistant Editor

Ted Sloan Contributing Editor

Cait A. Smith Copy Editor

Senior Kentributors

Jackie Hollenkamp Bentley, Jack Brammer, Bill Ellis, Steve Flairty, Gary Garth, Mick Jeffries, Kim Kobersmith, Brigitte Prather, Walt Reichert, Tracey Teo, Janine Washle and Gary P. West

Business and Circulation

Barbara Kay Vest Business Manager

Jocelyn Roper Circulation Specialist

Advertising

Lindsey Collins Senior Account Executive and Coordinator

Kelley Burchell Account Executive

Teresa Revlett Account Executive

For advertising information, call 888.329.0053 or 502.227.0053

KENTUCKY MONTHLY (ISSN 1542-0507) is published 10 times per year (monthly with combined December/ January and June/July issues) for $20 per year by Vested Interest Publications, Inc., 100 Consumer Lane, Frankfort, KY 40601. Periodicals Postage Paid at Frankfort, KY and at additional mailing offices.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to KENTUCKY MONTHLY, P.O. Box 559, Frankfort, KY 40602-0559.

Vested Interest Publications: Stephen M. Vest, president; Patricia Ranft, vice president; Barbara Kay Vest, secretary/treasurer. Board of directors: James W. Adams Jr., Dr. Gene Burch, Gregory N. Carnes, Barbara and Pete Chiericozzi, Kellee Dicks, Maj. Jack E. Dixon, Bruce and Peggy Dungan, Mary and Michael Embry, Thomas L. Hall, Judy M. Harris, Greg and Carrie Hawkins, Jan and John Higginbotham, Frank Martin, Bill Noel, Michelle Jenson McDonnell, Walter B. Norris, Kasia Pater, Dr. Mary Jo Ratliff, Barry A. Royalty, Randy and Rebecca Sandell, Kendall Carr Shelton and Ted M. Sloan. Kentucky Monthly invites queries but accepts no responsibility for unsolicited material; submissions will not be returned.

C. Casey Jones Distillery in Hopkinsville kentuckymonthly.com

2 KENTUCKY MONTHLY FEBRUARY 2023

Readers Write

Another Notable Thespian

Thanks for this great magazine, as I love Kentucky history. Just ask Jack Brammer.

I would like to add another name to Kentucky native actors (November 2022 issue, page 58). Henry Wadsworth was born on June 18, 1903, in Maysville. He was an actor, known for The Thin Man (1934), Applause (1929) and The Show-Off (1934). He died on Dec. 5, 1974, in New York City.

A stage and screen actor, Wadsworth was educated at the University of Kentucky and Carnegie Tech Drama School. He began in vaudeville and touring stock companies. Wadsworth appeared on Broadway in the late 1920s and in films for Paramount beginning in 1929.

Wadsworth served in the U.S. Navy during World War II and subsequently joined the USO in Japan, entertaining the armed forces stationed there. After he quit acting, he became a

union administrator and president of the AFL’s Film Council.

Ron Bailey, Maysville

Changes of Heart

When the December 2022/ January 2023 issue hit my mailbox, I turned to Bill Ellis’ article immediately (page 56). Since we are about the same age and had similar boyhood experiences, I never fail to enjoy and appreciate his musings.

This article was especially resonant for me. I recently published a memoir of my teenage years at a nowdefunct military school in Tennessee, 1957-1961. My parents chose that school rather than Kentucky Military Institute or Millersburg Military Institute because it was closer to our home.

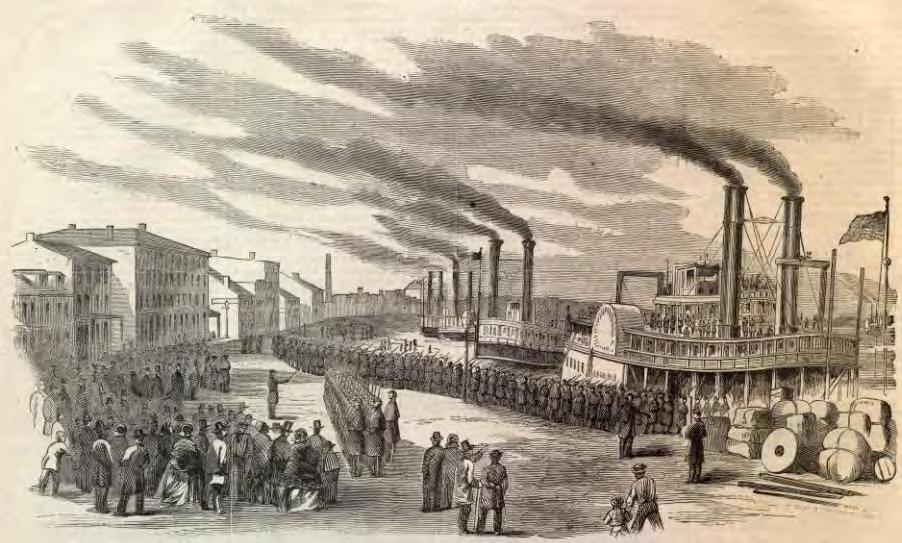

In reflecting on life in that era, I was reminded of the racial injustices and personal degradations that my peers and I perpetuated, mainly because that was

“the way it has always been.” As I noted in the book, a number of my fellow cadets (all white males) were there because of the nascent federal efforts at integration of public schools in the Deep South. Their parents were horrified at the prospect of their boys going to school with the “colored” kids. There is a generation (Mr. Ellis’ and mine) of white youth who found a way to overcome our segregationist past and work a sea change in our attitude toward our Black brothers and sisters. It was not easy, and it did not occur quickly—in some cases, the task is incomplete—but the changes are remarkable. Sometimes, I feel that our generation of white kids deserve a little more credit than we have been given for embracing the changes that have made us better people.

I enjoyed Mr. Ellis’ article and look forward to more of them.

Bill Harris, Franklin

The Kentucky Gift Guide Drink Local

Counties mentioned in this issue... kentuckymonthly.com 3

KENTUCKIANS EVERYWHERE.

editor@kentuckymonthly.com,

a letter

our website at kentuckymonthly.com,

message us

Facebook. Letters

be

clarification and

UNITING

We Love to Hear from You! Kentucky Monthly welcomes letters from all readers. Email us your comments at

send

through

or

on

may

edited for

brevity.

Find more at kentuckymonthly.com. Use your phone to scan this QR code and visit our website. Follow us @kymonthly

This handy guide to sipping in the Bluegrass State spotlights local breweries, wineries and, of course, distilleries. Discover unique ways to drink in Kentucky, creative cocktail recipes and more.

Kentucky Monthly’s annual gift guide highlights some of the finest handcrafted gifts and treats our Commonwealth has to offer.

MAG ON THE MOVE 4 KENTUCKY MONTHLY FEBRUARY 2023 Holiday Weekend Travels GERMANY + AUSTRIA Kim Boling Gross of Utica and her nephew, Jordan Boling of Louisville, visited Munich and Salzburg over Labor Day weekend 2022. Scan the QR code to upload a photo, or email a high-resolution photo, along with a caption to editor@kentuckymonthly.com travel Compare all options with just one call... AUSTIN TYLER LICENSED INSURANCE REPRESENTATIVE 859.618.6443 ANDREW HORN LICENSED INSURANCE REPRESENTATIVE 859.868.4006 TURNING 65? NEED MEDICARE ENROLLMENT HELP? MEDICARE ADVANTAGE QUESTIONS? 2333 ALEXANDRIA DRIVE, LEXINGTON, KY 40504 TYLERINSURANCEGROUP.COM Questions? We have answers! WE SPECIALIZE IN Medicare Supplement Plans Part D Prescription Plans Medicare Advantage PPO & HMO Plans Dental & Vision Options We do not offer every plan available in your area. Any information we provide is limited to those plans we do offer in your area. Please contact Medicare.gov or 1-800-Medicare to get information on all of your options. Not affiliated with the U.S. Government or Federal Medicare Program. Offering Life Insurance and Medicare DOWNTOWN FRAN K FO RT EAT • SHO P • EX PLORE vi si tfr ank fort.com SUBMIT A PHOTO

Even when you’re far away, you can take the spirit of your Kentucky home with you. And when you do, we want to see it!

European Travels

SWITZERLAND, ITALY + FRANCE

Greg, Irene and Morgan Longtine of Calhoun traveled around the three countries during a trip to attend a friend’s wedding. They are pictured in Switzerland, top, and Italy, above.

Island Time

SOUTH CAROLINA

The John D. Brock Sr. family of Pineville enjoyed a great week on glorious

Outdoor Adventures

CANADA

Kent Curtsinger of Fancy Farm traveled to a remote hunting camp in Newfoundland/Labrador Canada.

Stay 20 minutes from Louisville and enjoy award-winning horse farm B&Bs, bourbon & mead tours, quaint historic “Trains on Main” shopping & dining by the tracks, and fine farm-to-table dining in a racehorse barn. This Winter Escape can be found in ONE place in Kentucky. Only in Oldham

kentuckymonthly.com 5

Fall inLove with Oldham inWinter TourOldhamKY.com | 800-813-9953

Governor’s Awards in the Arts

The latest recipients of the Commonwealth’s most prestigious arts awards include a bluegrass legend, a folklorist, a high school band director and a sculptor, to name a few.

In all, nine artists, businesses and organizations have been named as recipients of the 2022 Governor’s Awards in the Arts. The winners are chosen from a list of nominations submitted to the Kentucky Arts Council on behalf of the Governor. They include Kentucky Gateway Museum benefactor Kaye Savage Browning of Maysville (Milner Award), Lexington’s Amanda Matthews (Artist Award), Independence Bank (Business Award), Murray Art Guild (Community Arts Award), Nan Moore (Education Award), Maxine Ray of Bowling Green (Folk Heritage Award), Kentucky Native American Heritage Commission (Government Award), Louisville’s Morgan Cook Atkinson (Media Award) and Leslie County’s Bobby Osborne (National Award).

All nine were honored at a ceremony in Frankfort in January. Each recipient was given a handcrafted, playable Navajo flute made by Mercer County artist Fred Nez-Keams. A 10th award is placed in the Arts Council’s permanent collection.

“The arts are transformational, and these Kentucky artists and organizations have used their talents to tell the stories of our Commonwealth,” Gov. Andy Beshear said. “I want to congratulate the nine honorees and thank them for their commitment to our Commonwealth and our people.”

KENTUCKY HIGH SCHOOL Teacher of the Year

Woodford County High School teacher

Amber Sergent may have been named the 2023 Kentucky High School Teacher of the Year, but she doesn’t like to brag. “I will be honest; I have struggled at times with the accolades that have been given to me,” she said. “There are so many others in our building and in this profession who deserve such awards. I have done my best to walk humbly with the attention. I do what I do not because of what I receive, but who I am.”

The social studies teacher was selected from hundreds of nominations submitted to the Kentucky Department of Education last year.

Sergeant has undergraduate and graduate degrees from Morehead State University and the University of Kentucky. She initially wanted to pursue law school but fell in love with the classroom.

“Kids these days may forget the content of my history courses, but they will never forget how we make them feel,” she said. “If I have achieved any success as an effective educator, it’s because my inspiration and my love come from those resilient and compassionate kids these days, who embrace vulnerability and practice courage every day.”

1 Arturo Alonzo Sandoval (1942), noted fiber artist and University of Kentucky art professor

5 Gary P. West (1943), Bowling Greenbased author and columnist

6 Tinashe (1993), R&B singer and actress from Lexington

10 John Calipari (1959), University of Kentucky’s Hall of Fame men’s basketball coach

12 Ed Hamilton (1947), renowned sculptor from Louisville

15 Chris T. Sullivan (1948), UK graduate who founded Outback Steakhouse

18 Mark Melloan (1981), folksinger/songwriter from Elizabethtown

20 Brian Littrell (1975), Christian singer/ songwriter from Lexington

20 Mitch McConnell (1942), U.S. Senate Minority Leader from Louisville

21 John Clay (1959), sports columnist for the Lexington Herald-Leader

24 Beth Broderick (1959), Falmouth-born television actress

26 Alexandria Mills (1992), Shepherdsville fashion model and Miss World 2010

27 Jared Champion (1983), Bowling Greenborn drummer for the band Cage the Elephant

27 Benny Snell Jr. (1998), running back for the Pittsburgh Steelers

across kentucky

6 KENTUCKY MONTHLY FEBRUARY 2023

FEBRUARY BIRTHDAYS

Explore infinite possibilities.

Experience high school differently. The Gatton Academy of Mathematics and Science offers gifted and talented high school juniors and seniors in Kentucky a chance to start college while finishing high school at Western Kentucky University. This two-year residential STEM program allows students to participate in college coursework full-time, pursue faculty-mentored research, study abroad, and thrive in a supportive community. With scholarships covering tuition, housing, and meals, students at Gatton can explore their interests in STEM. Explore your infinite possibilities at www.wku.edu/academy.

wku.edu/academy 270.745.6565 academy@wku.edu @gattonacademy

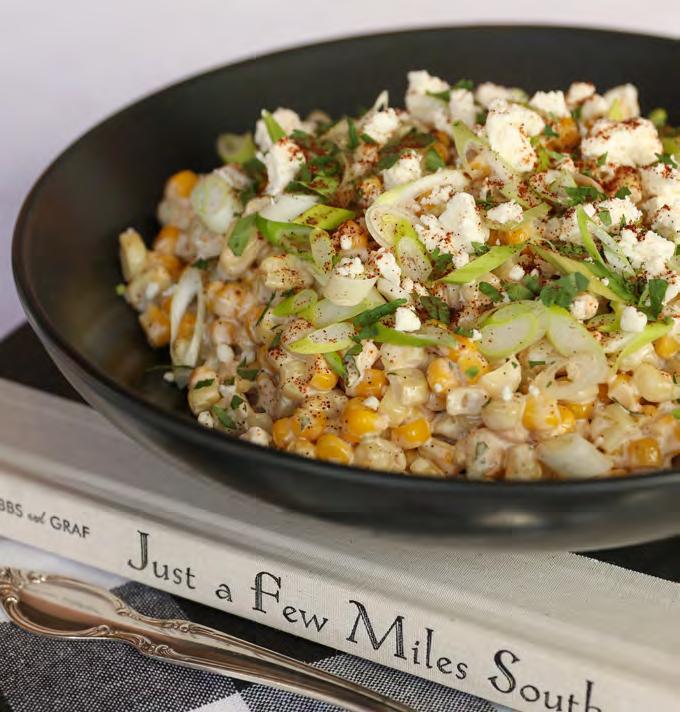

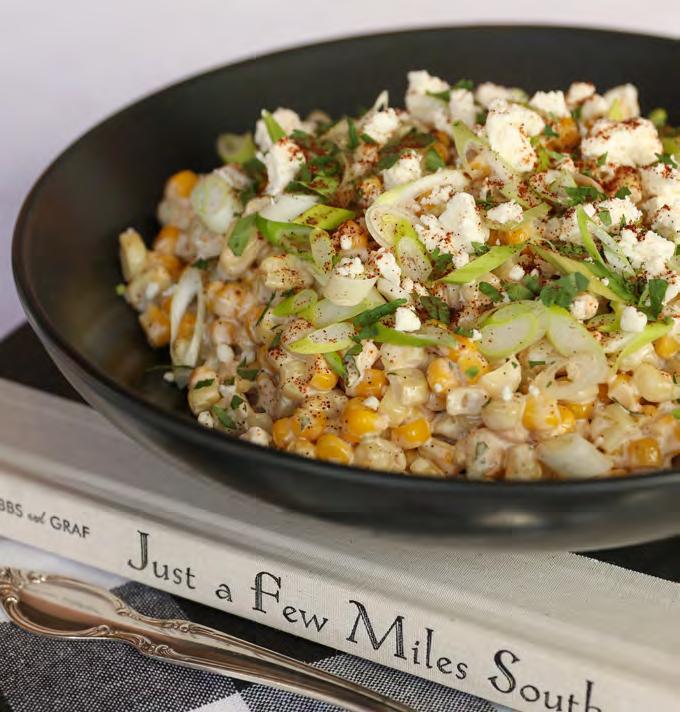

Just a Few Good Eats

Known primarily for her central Kentucky eateries, including the elegant Holly Hill Inn flagship restaurant in Midway, Chef Ouita Michel shared recipes for many of her delicious dishes in her cookbook

Just a Few Miles South: Timeless Recipes from Our Favorite Places , published in April 2021. Later that year, Chef Ouita launched the lifestyle brand Holly Hill and Co., celebrating local farmers, agriculture and culinary traditions, with a strong emphasis on community. Visitors to hollyhillandco.com will find stories, videos, merchandise, restaurant information and recipes, including those featured here.

Shady Lane Chicken Salad

Chef Ouita named her signature Wallace Station Deli chicken salad after Shady Lane, a scenic stretch of Old Frankfort Pike. The staff makes it in house every day with freshly prepared chicken, crisp celery, toasted almonds and sweet/tart dried cranberries.

YIELDS ALMOST 2 QUARTS

2 pounds boneless, skinless chicken breasts

Salt and pepper for seasoning

½ cup finely chopped celery

½ cup toasted slivered almonds

½ cup dried cranberries

½ teaspoon kosher salt

¼ teaspoon dry mustard

¼ teaspoon white pepper

¼ teaspoon black pepper

1½ tablespoons Dijon mustard

1 cup mayonnaise

1. Preheat oven to 350 degrees.

2. Spread chicken in a single layer on a baking pan and lightly season with salt and pepper. Cover with foil and bake until done (40 minutes or longer, depending on size).

3. Cool in the pan juice to retain moisture until the chicken is cool to handle. Cut into a small dice, discarding gristle and fat. Reserve pan juices for soup or another use.

4. Place chopped chicken, celery, almonds and cranberries in a large bowl. Set aside.

5. In another bowl, whisk together remaining ingredients and fold into chicken. Mix well. Taste for seasoning and add salt and pepper if needed. Remember that the chicken will absorb the dressing when refrigerated, so you might have to add a couple extra tablespoons of mayonnaise.

6. Chill at least 1 hour before serving.

8 KENTUCKY MONTHLY

2023 cooking

FEBRUARY

Happy Jack’s Corn Salad

SERVES 4 TO 6

5-6 ears fresh sweet corn in the husk

Lime aioli (ingredients follow)

Crumbled feta cheese, for garnish

Thinly sliced scallions, for garnish

Chopped cilantro, for garnish

Chipotle chili powder, for garnish

LIME AIOLI:

6 tablespoons mayonnaise

2 tablespoons sour cream

Zest of ½ lime

1 teaspoon fresh lime juice

¼ teaspoon chipotle chili powder

2 teaspoons chopped cilantro

½ teaspoon kosher salt

¼ teaspoon cayenne pepper

Benedictine

Holly Hill and Co.’s Benedictine recipe comes from former sous chef Lisa Laufer. This version of the cream cheese-based spread, named for legendary Louisville caterer Jennie C. Benedict, appeared in the preface of the updated version of Benedict’s The Blue Ribbon Cook Book, which originally was published in 1904. Benedictine spread is a staple at Kentucky Derby parties but delicious anytime. Aside from being a great sandwich spread, Benedictine is perfect for stuffing cherry tomatoes or topping hoecakes, especially with a sliver or two of Kentucky smoked trout.

1. For the lime aioli, mix together all ingredients with a whisk in a small bowl. Chill.

2. Cook the corn—still in the husk—by roasting in the oven, boiling in salted water or grilling. Cooking the corn in the husk makes removing the silk and husk much easier.

3. While still warm but cool enough to handle, cut the corn kernels from the cob and place in a large bowl.

4. Toss with the lime aioli and garnish with feta cheese, scallions and chopped cilantro, then dust with chipotle powder.

2 large cucumbers

12 ounces cream cheese, at room temperature

½ teaspoon onion juice or more to taste*

½ teaspoon kosher salt

3-4 dashes hot sauce

1. Peel and seed cucumbers, retaining a bit of skin for color. Purée in a food processor.

2. Squeeze purée in a cheesecloth or a clean tea towel, removing as much liquid as possible. This keeps the spread from being too runny and can be added back in if you want the mixture to be a bit looser.

3. Combine cucumber purée with the remaining ingredients in a mixer or a food processor and mix until smooth. Taste for seasoning.

Recipes provided by Holly Hill and Co. and prepared at Sullivan University by Ann Currie Photos by Jesse Hendrix-Inman.

*For onion juice, grate ¼ of a peeled sweet onion on a cheese grater and squeeze out the juice using cheese cloth.

kentuckymonthly.com 9

Damn Good Sugar Cookie

As written by Ouita Peyton , Ouita Michel’s maternal grandmother and namesake, and mom Pam Sexton , this is a generation-spanning recipe that has earned the title of being “Damn Good!”

FOR THE DOUGH:

1 cup softened butter

2 cups granulated sugar

4 eggs, beating in between each egg

½ cup sour cream

1 teaspoon baking powder

½ teaspoon baking soda

A pinch (¼ teaspoon) of salt

A dash of vanilla—about 1 scant teaspoon

Roughly 4 cups all-purpose flour

1. Cream together butter and sugar.

2. Add egg, sour cream, baking powder, baking soda, salt and vanilla.

3. Add enough flour to make a soft dough, starting with about 4 cups flour. May need a bit more.

Beaten Biscuits

John Egerton’s recipe, adapted by Chef Ouita

3 cups all-purpose flour (unbleached all-purpose from Weisenberger Mill recommended)

½ teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon baking powder

2 tablespoons sugar

½ cup butter, chilled and cut into small pieces

¾ cup buttermilk

4. Chill for at least one hour.

5. Roll out dough, cut into shapes, and bake at 375 degrees until lightly browned.

FOR THE ICING:

2-pound bag powdered sugar

1 cup butter

1 cup sour cream

1 ½ teaspoons vanilla

1. Melt the butter and transfer to a mixing bowl. Beat in the powdered sugar.

2. Add the sour cream and vanilla, then beat at high speed until creamy and fluffy.

3. Divide into bowls and color with food coloring.

1. Preheat oven to 350 degrees.

2. Sift together all the dry ingredients. Cut in the butter. Add the milk and make a stiff dough. Roll, baby, roll, until smooth and cracking. If you don’t have a biscuit brake, this can be done with a rolling pin.

3. After a few passes with a rolling pin or on a biscuit brake, fold dough back over on itself. Cut with a small biscuit cutter (the radius of a champagne flute). Prick the surface of each biscuit three times with a fork.

4. Bake for 20-25 minutes, turn the oven off, and let sit for a few minutes. Do not let them brown. Test doneness by either pinching sides or breaking one open.

10 KENTUCKY MONTHLY FEBRUARY 2023 cooking

kentuckymonthly.com 11 Nationally-Recognized Heart Care Heart & Vascular Institute (606) 430-2201 | pikevillehospital.org attention, home chefs... Kentucky Monthly's annual recipe contest is back following a pandemic-induced hiatus. Submit your favorite original recipe for a chance to win great prizes and see your dish featured in our May issue. SUBMIT YOUR RECIPE AT KENTUCKYMONTHLY.COM SUBMISSIONS DUE MARCH 13 ENTER KENTUCKY MONTHLY'S RECIPE CONTEST!

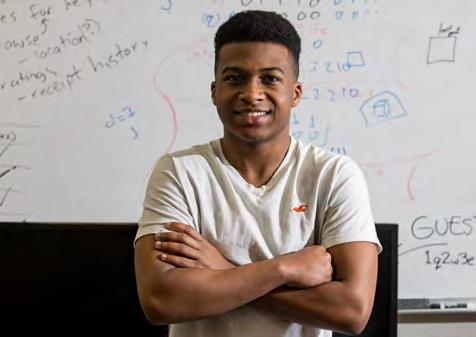

POET FOR THE PEOPLE

Ada Limón of Lexington wants to connect through her writing, her podcast and her post as the U.S. Poet Laureate

By Tom Eblen

By Tom Eblen

Photos by Lucas Marquardt

Twenty-four men and women have served as Poet Laureate of the United States since the post was created in 1936. It is the nation’s highest honor for a poet, and it comes with a beautiful office in the Library of Congress that has a view of the Capitol.

Three poets laureate have been Kentuckians. The first two, Robert Penn Warren and Allen Tate, were white men who were born in Kentucky but moved away to advance their literary careers. The third, and current, poet laureate from Kentucky has a much different story.

Ada Limón, 46, was born and raised in Sonoma, California, and is of Mexican ancestry. She graduated from the University of Washington in Seattle, where she was a theater major. Limón planned to study acting in graduate school, too, until she took an advanced poetry class her senior year from Colleen McElroy, who suggested she pursue writing instead.

After graduation, Limón took a year to write enough poems to get into the master of fine arts program at New York University, where she studied under poets Sharon Olds, Philip Levine, Galway Kinnell, Mark Doty and Agha Shahid Ali. During a dozen years in New York, Limón also worked for several magazines and published her first three poetry collections: Lucky Wreck (2006), This Big Fake World (2006) and Sharks in the Rivers (2010).

Then Limón moved to Kentucky, and her literary career blossomed.

At first, Limón didn’t want to live in Kentucky. She even wrote a poem about it that was published in The New Yorker. But she followed her boyfriend (now husband) Lucas Marquardt to Lexington in 2011. A former award-winning journalist for the Thoroughbred Daily News, Marquardt was starting his own company, ThoroStride, which makes inspection videos of Thoroughbred racehorses going to auction.

“His business brought us here, and it’s been a really wonderful place for me to explore my art,” Limón said in one of two interviews I have done with her for WEKUFM’s weekly program Eastern Standard. “I was surprised that Kentucky gave me two of the things I didn’t know I needed to flourish as an artist … time and space.”

It didn’t take long for Limón to fall in love with Kentucky, especially the landscape and slower pace of life. She has a passion for the natural world, which often is reflected in her poetry. She was mesmerized by Kentucky’s fireflies, which she had never seen before. She wrote a poem about them titled “Field Bling.”

“Kentucky is gorgeous!” Limón said while taking questions after a reading last November at Transylvania University. “I don’t think people talk about that enough. I always take my family out to the Red River Gorge when they come to visit, and they’re blown away by it.”

Then she added: “I think the other thing that surprised me, and has sustained me, is the incredible community of writers and artists that live in this city. There are just so many amazing writers here and artmakers, and I don’t think that is talked about enough.”

Three of Limón’s six poetry collections were written after she moved to Kentucky: Bright Dead Things (2015), a finalist for the National Book Award for Poetry and the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry; The

Carrying (2018), which won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry and was a finalist for the PEN/ Jean Stein Book Award; and The Hurting Kind (2022), which The New York Times and NPR included on their lists of best poetry books of the year.

Also last year, Limón produced Shelter: A Love Letter to Trees, an e-book and audiobook she narrated, published by Scribd. She received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2020. Her next book will be Beast: An Anthology of Animal Poems, a collection of work from major poets. “I am obsessed about animals,” she said. “My dog is snoring at my feet as I say this.”

If poet laureate is the most visible job an American poet can have, perhaps the second-most visible is as host of The Slowdown, a daily podcast produced by American Public Media and the Poetry Foundation. Tracy K. Smith started the show in 2019 when she was the U.S. poet laureate. When Smith decided to step down as host, the producers reached out to Limón, who took over in September 2021.

The Slowdown is a 5- to 7-minute podcast in which Limón reads a brief essay she has written, then reads a poem by another poet that she and the producers have chosen. The podcast’s goal is to give poetry a more visible and influential place in American culture. Limón said her essays aren’t intended to describe each day’s poem but rather to put listeners in a frame of mind to absorb it.

The Slowdown has turned out to be the perfect forum for Limón, a trained actor with a mesmerizing voice. Her essays, like her poetry, are beautiful and often deeply personal. She has revealed her struggles with scoliosis and infertility, and sometimes mentions her beloved pug, Lily Bean. She occasionally refers to her life in Kentucky and places where she likes to be with nature, such as the Red River Gorge and McConnell Springs.

“I was surprised, to be honest, how much I enjoyed writing those brief essays,” she said. “What I’d love is for the podcast to reach people who aren’t necessarily thinking about poetry on a daily basis ... but can be welcomed into the world of poetry and the sound of poetry and have a moment when they’re not just sort of reflecting on their own life but feel connected to the lives of other people.”

Limón announced in January that, after 250 episodes and the poet laureate appointment, she was turning The Slowdown’s hosting duties over to poet Major Jackson.

Our relationships with nature and community are at the core of Limón’s poetry, and she finds writing to be therapeutic.

“I think it’s very easy to get bogged down by the sorrow and trauma and real issues of today,” she said. “And at the same time, if we don’t recommit to the world and we just give up, oh what a horrible consequence. So, I want my poems to help me recommit to the world. And I hope—I really hope—that they will help others do the same. To sign up again, to sign up to life.”

kentuckymonthly.com 13

• • •

• • •

It’s not surprising that Limón attracted the attention of the Librarian of Congress, who appoints the poet laureate. But Limón was surprised. Flabbergasted, actually.

She said Vaughan Ashlie Fielder, a close friend who represents her and several other major poets through her Lexington-based agency The Field Office, told her she needed to take a mysterious Zoom call on June 1, 2022, at exactly 9:35 a.m.

“She wouldn’t tell me what it was about, but she said, ‘You might want to get dressed up for this one,’ ” Limón recalled. “I logged on, and there, in the center of the Zoom call, in the grid of Zoom, was Dr. Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress. She was with her team, and she just said, ‘I would like to invite you to be the 24th Poet Laureate of the United States.’ The shock of the news sort of sent me out of my body.”

Poet laureate is a public job that is privately funded through an endowment left by the late scholar and philanthropist Archer M. Huntington. Poets laureate are

appointed annually but often serve two terms. The last poet laureate, Joy Harjo, got a rare third year.

“Ada Limón is a poet who connects,” Hayden said in announcing the appointment. “Her accessible, engaging poems ground us in where we are and who we share our world with. They speak of intimate truths, of the beauty and heartbreak that is living, in ways that help us move forward.”

While the poet laureate has a few official speaking duties, most of the work involves promoting poetry to a wider audience. Limón has eagerly embraced the role, saying she believes poetry can help heal us after tumultuous years of pandemic, political division and culture wars.

“I think one of the ways that poetry helps people reclaim their humanity is through deep attention,” she said. “Poetry is that way of spending a moment remembering that you are a thinking, feeling, alive human being living in the world.” Q

14 KENTUCKY MONTHLY FEBRUARY 2023

THE CENTER FOR GIFTED STUDIES

Climb With Us

Graduate Programs

■ The Gifted and Talented Endorsement

■ MAE in Gifted Education and Talent Development

■ EdS in Gifted Education and Talent Development Programs for Gifted Students

■ Super Saturdays

■ The Summer Camp for Academically Talented Middle School Students

■ The Summer Program for Verbally and Mathematically Precocious Youth

■ Camp Explore

■ Camp Innovate

Other Amazing Programs

■ IdeaFestival Bowling Green

■ Travel Abroad

■ Professional Development

■ Talent Identification Program of Kentucky (TIP-KY)

■ And so much more!

Learn more at wku.edu/gifted 270-745-6323 | gifted@wku.edu

kentuckymonthly.com 15

Kentucky Writers 2023

Hall of fame.

LEARN MORE AT CARNEGIECENTERLEX.ORG

16 KENTUCKY MONTHLY FEBRUARY 2023

Suzan-Lori Parks was the first African American woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for drama. More than two decades later, she dominates this year’s New York theater season with a 20th anniversary revival of her prize-winning play plus three new works, including one in which she performs.

Another Kentucky-born playwright, Marsha Norman , is a legend of stage and screen. She has won a Pulitzer Prize, two Tony Awards and dozens of other major honors.

Former state poet laureate Richard Taylor stayed in Kentucky and made its rich history and landscape the material for his awardwinning poetry, novels and nonfiction books.

These three living writers will be inducted into the Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame on March 23 in a ceremony at the historic Kentucky Theatre in Lexington. Joining them will be two deceased poets, Madison Cawein and Blanche Taylor Dickinson , who have largely been forgotten since they achieved fame more than a century ago.

Learn more about these Kentucky literary icons in this special section, written by Tom Eblen , a former Lexington Herald-Leader columnist and managing editor who is now the literary arts liaison at the Carnegie Center for Literacy & Learning.

kentuckymonthly.com 17

. SUZAN-LORI PARKS .

five years ago, The New York Times’ theater critics declared Topdog/Underdog, by Kentucky-born playwright Suzan-Lori Parks, the best American play of the previous quarter century—the best since Tony Kushner’s Angels in America rocked the theater world in 1993.

The play won Parks the 2002 Pulitzer Prize in drama, making her the first African American woman to receive the award. A critically acclaimed 20th anniversary revival of Topdog/Underdog opened at New York’s John Golden Theatre last fall, starring Corey Hawkins and Yahya AbdulMateen II and directed by Kenny Leon

But Parks, 59, has never been one to rest on accolades— or even pause long to take a deep breath. A creative dynamo, she seems to spin faster with age.

Her dramatic works have been in production for an astounding 35 years. She has written literally hundreds of plays, including more than two dozen stage plays, radio plays and screenplays that have been produced for major venues. She decided in 2002 to write a play a day for an entire year. Then, 18 years later, she launched another play-writing marathon during the pandemic.

Parks has published one novel and is writing a second. She is an accomplished essayist and a songwriter who plays guitar in a band with her husband, Christian Konopka, when they’re not busy raising their 11-year-old son. She teaches at New York University and the Public Theater in New York, where she is the writer in residence.

Topdog/Underdog is one of four Suzan-Lori Parks plays running in New York this season. The other three are new works. Sally & Tom, about Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson, premiered at the Guthrie Theater last fall. The Public Theater is presenting the other two plays this winter and spring: Plays for the Plague Year, in which Parks performs, and The Harder They Come, an adaptation of a 1972 movie for which she wrote the book and three new songs.

“I’m having fun,” she said in a telephone interview from her NYU campus apartment. “The work itself is this beautiful thing that life has afforded us.”

Parks was born at Fort Knox on May 10, 1963, to a career Army officer and an educator. When she was a toddler, the family was transferred. But they moved back to Kentucky when she was in elementary school, and Parks has fond memories of growing up here. Those

Kentucky years influenced her future work, including her most famous play.

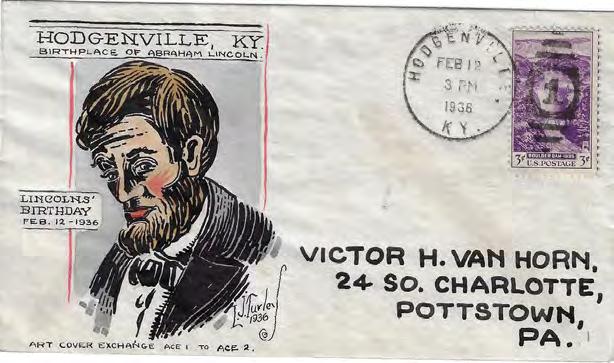

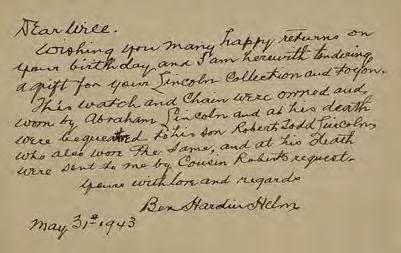

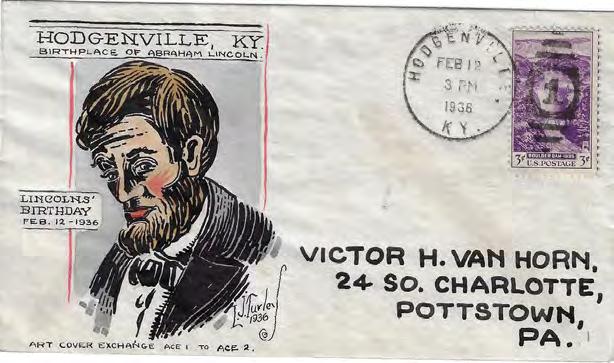

Topdog/Underdog, a darkly comic story about sibling rivalry and family relationships, features two African American brothers named Lincoln and Booth. You can guess how the play ends. Parks, who has always been fascinated by history, remembers childhood trips to Abraham Lincoln’s birthplace near Hodgenville. “And my birthday’s on John Wilkes Booth’s birthday,” she said.

“I loved Mammoth Cave especially,” she said. “The landscape was very meaningful to me and is to this day. For years, I had a rock collection, which started in Kentucky as a kid in second grade.”

The first of Parks’ plays to be produced in New York also had a Kentucky angle. Betting on the Dust Commander (1987) is a humorous look at the endless repetition of daily life, and its action centers around the Kentucky Derby.

The Army kept Parks’ father, who eventually retired as a lieutenant colonel, on the move. In addition to Kentucky, she grew up in West Germany, California, North Carolina, Texas, Vermont and Maryland. While in high school, she fell in love with playing guitar.

“I started out as a musician but then sort of moved into writing because it felt like a safer profession,” she said. “The music scene is kind of dicey, fraught with intense energy, which is less safe than the library. I had an early love for the library. I would sit in the library wherever we lived. Those were some of my favorite places, sitting among the books.”

Parks earned a B.A. in English and German literature (Phi Beta Kappa) from Mount Holyoke College. She studied with James Baldwin, who encouraged her to pursue dramatic writing. She resisted at first but soon realized he was right.

“It’s not the imitation of life; it is actually life,” she said of drama. “Once you get to the moment of the curtain up at 7 o’clock at the Golden Theatre on Broadway, those people in the show, they’re alive. And the people in the seats are alive. And at the end of the day, literally, when they take their bows, it’s about what it means to be alive, what it means to be a community. I love action and activity. I love all the things about theater. It’s not just action. It’s not just dialogue. It’s not just description. It’s not just narrative arc. Often, it includes song. It includes interacting with living people.”

18 KENTUCKY MONTHLY FEBRUARY 2023

About her novel writing, Parks said, “It’s also a joyous experience but very different because the interaction with the audience is not as momentby-moment. Drama and theater just have so much to offer, so many challenges, and you have to be good at so many things. And at the end, you have to get along with people enough so that they’ll do your play. You can’t just be that writer in the ivory tower saying, ‘Aren’t I brilliant? Publish this!’ You have to actually be in there with folks and be responsive to the needs of the community while also keeping your eye on the needs of the spirit.”

Parks’ plays have been winning awards since 1990, when she received an Obie for the best new American play (Imperceptible Mutabilities in the Third Kingdom). She received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2000, the same year she was a Pulitzer finalist for In the Blood. She was a finalist again in 2015 for Father Comes Home From the Wars, Parts 1, 2 & 3. (When she won the Pulitzer for Topdog/Underdog, the original production was directed by Frankfort native George C. Wolfe, who had directed Angels in America in 1993.)

When the MacArthur Foundation awarded Parks one of its lucrative “genius” grants in 2001, it noted that her “risk-taking, dramatic presentations reflect and refract social imagery from American culture and history. By creating compelling stories and characters that dramatize the complex influences that form both individual and collective identity, her explorations challenge us to reconsider our perceptions of others and ourselves.” The foundation added that her plays “are characterized by her signature use of provocative stagecraft, gritty colloquialisms and wordplay inspired by the looped and spiraling forms of jazz.”

For any writer to be so productive, so creative and so successful for so long, it begs the question: How does she do it?

“It’s just showing up,” she said. “One of the first awards I ever got—I still have it on my bookshelf. I’m looking at it now. My dad was in Vietnam. We were in Texas with my mom’s family. I went to St. Mary’s School, and I was in kindergarten or first grade. Perfect attendance. That was my first award. And I was like, ‘Yeah!’ You just keep showing up!”

A schedule also helps. “Am I organized?” she replied with a laugh when asked. “I’m the daughter of an Army colonel! I was born at Fort Knox, baby! My mother, who has a master’s degree and was an educator, just retired last year. So, we are a family of … well, we can get stuff done!”

Parks rises early each morning, writes in her notebook, and gets her son off to school. (She says parenting is often a tagteam effort with her husband, a night-owl musician.) She then does yoga and gets to work, measuring intensely focused writing stints with a kitchen timer.

“You’re not waiting for inspiration; you’ve just got to do it,” she said. “I write sometimes really awful first drafts. Sometimes, you have to, because sometimes, that’s all you got. Sometimes, you gotta just like slop it out there to see what you’ve got, and then you gotta make it better. Often, it’s all in the rewrite. And that takes a certain organization of the mind, organization of the spirit.”

She frequently offers this advice in a free writing class she hosts most Monday afternoons called Watch Me Work. Held in the Public Theater’s lobby until the pandemic forced it online, the class is open to writers of any level. They write along with her in silence for 20 minutes—there’s a kitchen timer—and afterward ask her questions and discuss the creative process.

“It’s a passion project,” she said. “It’s an opportunity for me to share freely ... just to be there for people who are at any stage or level of their creative process. You don’t have to have gotten into a grad school; you don’t have to have afforded tuition or gotten a grant. You just show up, and I’ll talk to you about your writing. And it really means something to people. It says, ‘You matter. I see you trying to do your thing.’ ”

Parks’ success also has come from taking advantage of opportunities, which at times were cleverly disguised as roadblocks. Plays for the Plague Year, which opens April 5 at the Public Theater venue Joe’s Pub, chronicles a year that shook American society to its core. With guitar in hand, she and seven actors perform three hours’ worth of short plays.

“I thought I might write 14 of these; it would be cute, a little thing for me to do during a brief hiatus,” she said. “And then the hiatus turned into a pandemic, and I kept writing. I had no idea that the year was going to be the year that it was—what with the pandemic, what with the vaccine coming, what with the mask troubles, what with George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, the election and all the strife and the interesting times. It suddenly exploded into a very interesting year. I had no idea about that. But I did just keep showing up.” Q

kentuckymonthly.com 19

kentucky writers hall of fame

MARSHA NORMAN .

kentucky writers hall of fame

marsha Norman is a prolific playwright, screenwriter and novelist who since the early 1980s has been one of the best-known writers in American drama. She has won the Pulitzer Prize, two Tony Awards and a long list of other major honors.

Norman was born Sept. 21, 1947, in Louisville and grew up near Audubon Park, the oldest of two daughters and two sons of an insurance salesman and a homemaker. She has described her childhood as isolated, which she said turned out to be good for a future writer. Many of her plays are about family dynamics and relationships.

Norman was asked in a 1993 interview with Kentucky writer Elizabeth Beattie what was the most important thing she felt she was doing with her work.

“Dramatizing these moments of courage,” she replied, “moments of courage belonging to people you would not expect were equipped to deal with it.”

Norman graduated from Agnes Scott College in Decatur, Georgia, and earned a master’s degree from the University of Louisville. She wrote for the Louisville Times and Kentucky Educational Television and worked as an educator in Jefferson County.

The first of Norman’s 14 stage plays, Getting Out, was produced at the Actors Theatre of Louisville and then Off Broadway in New York in 1979. The play is about a young woman paroled after an eight-year prison sentence for robbery, kidnapping and manslaughter. It was inspired by Norman’s experiences working with disturbed adolescents at Central State Hospital in Louisville.

Norman became famous after the New York production of her play ’night, Mother about a divorced woman, Jessie Cates, who lives with her mother, Thelma Cates. Over the course of an evening, Jessie calmly explains to Thelma that she plans to commit suicide and why. The play won Norman the 1983 Pulitzer Prize in drama, a Drama Desk

Award and a Tony Award nomination.

Norman’s first love was music; she began playing piano at age 5. For years after her success with ’night, Mother, Norman longed to write for a Broadway musical. “I felt very trapped in the world of the tragic drama, and I wanted out of there,” she told Beattie.

Norman finally got her chance by adapting Frances Hodgson Burnett’s 1911 novel The Secret Garden into a musical, and it won her Tony and Drama Desk awards in 1992. She went on to write the book for the Broadway musical of Alice Walker’s novel The Color Purple, winning a Tony nomination for the original 2005 production and a Tony Award for the 2016 revival. Her five musical adaptations for theater also have included The Trumpet of the Swan, The Bridges of Madison County and The Red Shoes

Norman has been a prolific writer for television and film, with credits on a dozen projects. She won a 2009 Peabody Award for her work on the HBO series In Treatment. She also has written a novel, The Fortune Teller (1989), which explores parent-child relationships.

Norman’s other awards include the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Guild Hall Academy of Arts & Letters and the William Inge Distinguished Lifetime Achievement in Theater. She is a member of the Theater Hall of Fame. Norman has received awards and grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Rockefeller Foundation and the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, along with 18 honorary degrees from American colleges and universities.

She was co-chair of playwriting at The Juilliard School for 25 years until her retirement in 2020. She lives in the Berkshires in western Massachusetts. Q

20 KENTUCKY MONTHLY FEBRUARY 2023

.

RICHARD TAYLOR .

kentucky writers hall of fame

after earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English, Richard Taylor couldn’t decide on a career. His father, a trial attorney, suggested law school, so that occupied the next three years of his life.

“I practiced in his law firm about four or five months,” Taylor said in an interview. “Then I got out in the public interest. I knew I wasn’t cut out for it, and I wanted to write.”

Taylor took brief jobs at two Mississippi junior colleges to make sure he liked teaching. Then, he went back to the University of Kentucky and earned a Ph.D. in English, studying under Hall of Fame writer Guy Davenport. Taylor joined the faculty at Kentucky State University and began a prolific career as a Kentucky-focused poet, essayist, novelist, nonfiction writer and teacher.

Taylor may be best known as a poet, having served as Kentucky’s poet laureate from 1999-2001. The first of his 12 poetry collections, Bluegrass, was published in 1975 as one of the first books printed by Gray Zeitz at his legendary Larkspur Press in Owen County. Last year, as Taylor turned 81, he published his two most recent poetry collections: Bull’s Hell (Larkspur) and Snow Falling on Water: Selected and New Poems (Accents Publishing).

“I was drawn to poetry because poetry could be written on the run, so to speak,” Taylor said. “Working on a poem has gotten me through more than one faculty meeting.”

Taylor found that he loved teaching almost as much as writing. While at Kentucky State, he regularly taught high school students in the summer Governor’s Scholars program. After retiring, he moved to Transylvania University as the Kenan Visiting Writer. He stepped down from that role last year. “I like working with young people,” he said. “I like constantly being confronted with ideas. I like an academic environment—if they would just drop the meetings and some of the protocols. I liked having time in the summer to write. Time over the holidays to write. I would not have had that practicing law.”

In addition to his dozen poetry books, Taylor has written two novels—Girty (1990) and Sue Mundy: A Novel of the Civil War (2006)—and four books of nonfiction: Three Kentucky Tragedies (1991), aimed at adults learning to read as part of a statewide literacy program; The Palisades of the Kentucky River (1997); The Great Crossing: A Historic Journey to Buffalo Trace (2002); and Elkhorn: Evolution of a Kentucky Landscape (2018).

Taylor’s work has focused on Kentucky’s colorful history and beautiful landscape. He was born in Washington, D.C., but grew up in the Crescent Hill area of Louisville. “The Taylors have been around here a long time,” the sixthgeneration Kentuckian said. “Some people say too long.”

Taylor’s earliest ancestor to set foot in Kentucky was Reuben Taylor, who came in the 1770s as a teenaged

surveyor from Virginia and settled near Louisville on land that is now part of Norton Commons. Reuben Taylor’s log cabin still stands, and Taylor and his brother are trying to preserve it.

Taylor has always been fascinated by the violent misfits of Kentucky history, such as the subjects of his two novels, Simon Girty and Sue Mundy. Girty fought with Indians and the British against white settlers in Kentucky. Mundy was the fictional name a Louisville newspaper editor gave to Confederate Capt. Marcellus Jerome Clarke, a young raider who had long hair and a baby face. Union soldiers captured Clarke in March 1865 and hanged him at the age of 20 in Louisville.

Three of Taylor’s poetry books have been episodic, narrative biographies of famous Kentuckians—Rail Splitter: Sonnets on the Life of Abraham Lincoln (2009); Rare Bird: Sonnets on the Life of John James Audubon (2011); and the recently published Bull’s Hell: Poems on the Life of Cassius M. Clay. “It’s such a durable and pliable form,” Taylor said. “And they were a lot of fun to do.”

Taylor’s book Elkhorn, winner of the 2018 Thomas D. Clark Medallion for the best book about Kentucky’s history or culture, chronicles an 8-mile stretch of Elkhorn Creek near Frankfort, where he lives in a rambling, book-filled house built in 1859.

Like Girty, Elkhorn is a mix of prose, poetry and imagined monologues. Taylor loves to play with language and doesn’t like to be tied down to one form of writing—or creativity. He is an avid watercolorist and sketch artist, making his own ink from black walnut hulls. The daily journals he has kept since 1984—he is now on volume 258—are filled with drawings and paintings as well as words.

“I think the best writing—fiction writing, poetry—relies on images,” he said. “I’m very much attracted to the visible world. So, the two kind of feed on one another.”

Taylor is finishing a book of essays about father figures. There are recollections of his own father, Joe Howard Taylor, the lawyer who wanted to be a landscape architect until he discovered he couldn’t draw. Another essay is about an uncle who lived with Taylor’s family when he was growing up. Louis F. Dey was an artist and photographer who helped inspire Taylor’s love of language and history.

Taylor has no grand plan for choosing writing projects. “I just go where whim leads me,” he said. “A lot of what I get interested in is something I hear or read and then think, ‘I’d like to know more about this.’ I have amassed such a library that I can do a lot of research right here.”

Part of that library owes to the fact Taylor is co-owner of Poor Richard’s Books in Frankfort, run since 1978 by wife Lizz Taylor, from whom he is separated. “Lizz is a first-rate businesswoman,” he said. “I joke that the place tends to prosper to the extent I’m not connected with it.” Q

kentuckymonthly.com 21

.

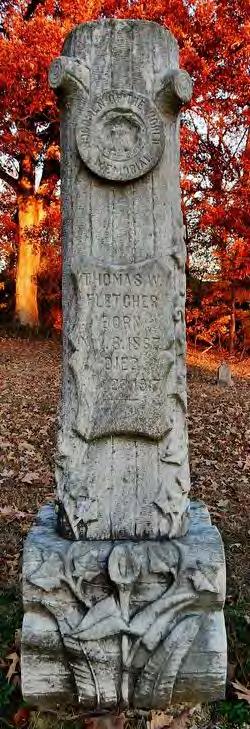

BLANCHE TAYLOR DICKINSON .

Blanche Taylor Dickinson was a poet, short story writer and journalist whose work was published in several magazines and newspapers in the 1920s. Her poetry has been widely anthologized with the work of other Black poets of the Harlem Renaissance.

Dickinson was born in Franklin (Simpson County) on April 15, 1896, to farmers Thomas and Laura Taylor . She attended segregated schools in Simpson County, Bowling Green Academy and Simmons College in Louisville and taught in public schools.

One of her earliest published poems appeared in the local newspaper, The Franklin Favorite, in July 1925. Dickinson and her husband, truck driver Verdell Dickinson, lived in his hometown of Trenton in Todd County.

Two years later, the couple lived in Sewickley, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh, and she was among several Black writers and artists featured in the magazine Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life. The magazine awarded her a Buckner Prize that year for “conspicuous promise” and for her poem “A Sonnet and a Rondeau.”

“As far back as I can remember I have had the urge to write poetry and stories,” Dickinson told the magazine. “My mother says that her youthful dreams were based on the same idea and perhaps she gave it to me as a prenatal gift. I do write a salable story once in a while and an acceptable poem a little oftener. The American Anthology [Unicorn Press], just released, contains three of my poems. I am intensely interested in all the younger Negro writers and try to keep in touch with them through the Negro press.”

Over the next three years, Dickinson’s poetry would be published in numerous magazines, including Opportunity, W.E.B. Du Bois’ The Crisis and Caroling Dusk. Her work also appeared in newspapers such as the Chicago Defender, the

Louisville Leader, the Longview (Texas) News Journal and the Pittsburgh Courier. In 1929, two white-owned poetry magazines, The American Poet and Bozart, published her work. She and her work have been featured in several books about the Harlem Renaissance poets.

In the late 1920s, Dickinson wrote regularly for the Pittsburgh Courier, publishing short fiction, including a four-part romantic serial “Nellie Marie from Tennessee.” She also wrote news notes columns for the Courier called “Smoky City’s Streets” and “Valley Echoes.” She interviewed aviator Amelia Earhart in 1929 for the Baltimore Afro-American.

Much of Dickinson’s poetry reflected upon the difficulty of Black women’s lives in the 1920s. It commented on racism, class, patriarchy and standards of beauty determined by white culture. “In her poem ‘Fortitude,’ Dickinson portrays the woman of the silent scream, the denial of her person, and her acceptance with a countenance of pride and a broken spirit,” Helen R. Houston wrote in the book Black Women of the Harlem Renaissance Era (Rowman & Littlefield, 2014).

Dickinson’s literary output stopped around 1930. The 1940 census showed her back home in Kentucky, living with her father and a widowed aunt and working as a schoolteacher. That census listed her as a widow. But according to other records, her husband, who was two years younger, didn’t die until 1978, in Pittsburgh. In later years, she went by the name Patty Blanche Taylor, which is how her tombstone reads.

She died in January 1972 at age 75 at Western State Hospital in Hopkinsville. Records after her death show that she had little money. Earl Burrus, a Black community leader and funeral director in Franklin, established a fund for her benefit. She is buried in Pleasant View Cemetery in Simpson County. Q

22 KENTUCKY MONTHLY FEBRUARY 2023

.

kentucky writers hall of fame

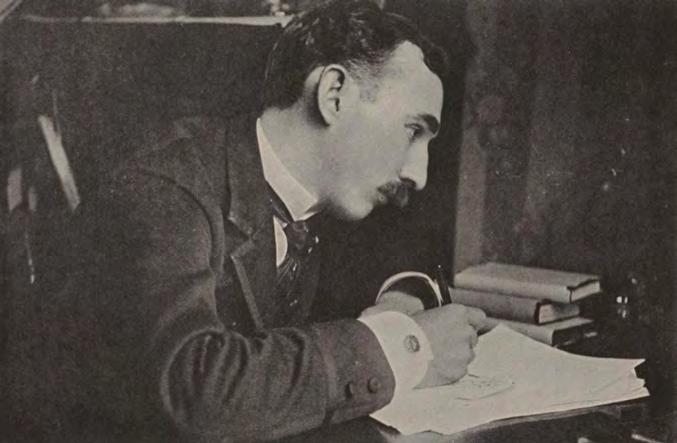

MADISON CAWEIN .

kentucky writers hall of fame

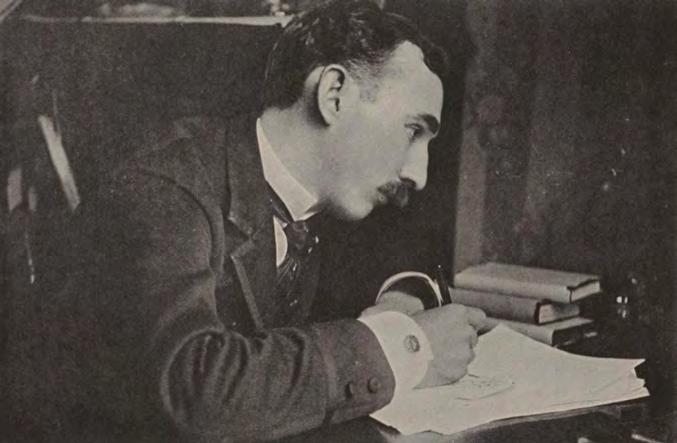

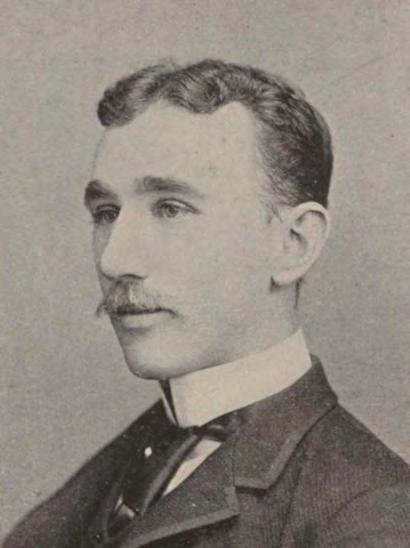

madison Julius Cawein was an internationally known romantic poet in the decades before and after the turn of the 20th century. Most of his poetry was about nature, extolling the beauty of the countryside around Louisville. Comparisons to the British poets Percy Shelley and John Keats earned Cawein the nickname “the Keats of Kentucky.”

Cawein was born in Louisville on March 23, 1865, to William Cawein—a confectioner, chef and herbal doctor—and Christina Stelsley Cawein, a spiritualist. The couple had four sons, one daughter and little money.

When Cawein was 9, the family moved to rural Oldham County, where his father managed the Rock Springs Hotel for nearly two years. They later lived on a 20-acre hilltop farm near New Albany, Indiana, for three years. “Here I formed my great love for nature,” he wrote.

The family returned to Louisville in 1879. Cawein graduated from Male High School in 1886 and was selected “class poet.” Unable to afford college, he worked as a cashier at the Newmarket pool room, a center for horse race gambling, and read classic literature when things weren’t busy.

In 1887, at age 22, Cawein used his savings to publish Blooms of the Berry, his first collection of poems. It caught the attention of novelist and critic William Dean Howells, who gave it a favorable review in Harper’s magazine. They became lifelong friends.

After working at the Newmarket for nearly eight years, Cawein had earned enough money through savings and investments to quit and devote himself to writing. Cawein spent much of his free time roaming the woods around Louisville. He also made country rambles with his father, who was looking for medicinal plants to make the patent medicines he sold.

“Poetry I define as the metrical or rhythmical expression of the emotions, occasioned by the sight or the knowledge of the beautiful and the noble in ourselves,” Cawein wrote in a 1905 letter to Lexington author John Wilson Townsend.

Cawein lived for many years with his parents in a house at 19th and Market streets, where he wrote 19 books. That house is now Legacy Funeral Center –Schoppenhorst Chapel. Cawein married Gertrude McKelvey in 1903, and they had a son, Preston Hamilton Cawein, the next year. In 1917, the son’s name was changed to Madison Cawein II.

The Poetry Review of London wrote in 1912 that Cawein “appears quite the biggest figure among American poets.” His many fans included President Theodore Roosevelt and Indiana poet James Whitcomb Riley. Cawein was a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters and the Authors Club of London.

Over three prolific decades, Cawein wrote more than 1,500 poems and published 36 books. He told a CourierJournal reporter in 1901 that his income from publishing poetry in magazines the year before amounted to about $100 a month, now the equivalent of about $3,500. He was a successful investor until the last two years of his life, when he suffered serious financial troubles, which forced him to rent out his beloved home on St. James Court and move with his family to an apartment across the street.

Cawein died in that apartment on Dec. 8, 1914, from an apparent stroke, several days after falling and hitting his head on the bathtub. He was 49. He is buried in Cave Hill Cemetery.

“He saw and felt the poetry of nature,” the CourierJournal editorialized upon his death, “and it was his unswerving purpose to give it voice.”

Cawein’s romantic style of poetry was falling out of fashion toward the end of his life, but he made a contribution to what would come next. In 1913, Cawein published a poem titled “Waste Land” in a Chicago magazine whose editors included Ezra Pound. Scholars have identified this poem as an inspiration for T.S. Eliot’s poem “The Waste Land,” published in 1922 and considered an early example of modernism in poetry. Q

24 KENTUCKY MONTHLY FEBRUARY 2023

.

kentucky monthly ’s annual

P E N N E D

writers’ showcase

26 KENTUCKY MONTHLY FEBRUARY 2023

2023 WINNING SUBMISSIONS

John E. Campbell Roger Guffey

Marie Mitchell

Bruce Bishop

J.M. Helm

Kaitlyn McCracken

Courtney Music

Robert L. Penick

Amy Le Ann Richardson

Rosemarie Wurth-Grice

2023 Penned winners AND the finalists listed below also are published online. Scan

FINALISTS

FICTION

Katie Hughbanks Louisville

Brook West Lexington

NONFICTION

Marlayna Kitchen Ashland

Susan Willmot King City, Ontario

Eric Nance Woehler

Madisonville

POETRY

Sylvia Ahrens Lexington

Libby Falk Jones Berea

Patrick Johnson

Morehead

Samar Johnson

Lexington

McKenna Revel

Mount Sterling

Hailey Small Wilmore

kentuckymonthly.com 27

poetry nonfiction fiction

SCAN FOR MORE

the code

visit our website

read more.

or

to

fiction For I Was Hungry …

ROGER GUFFEY, LEXINGTON

Fathers and sons have striven mightily since the dawn of time, often over trivial disagreements that escalate into hot-blooded animus long after the roots of their conflicts are lost. The feud sometimes becomes the raison d’être that sustains estrangement of people who once truly loved each other.

Clayton Kelly had not spoken to his son Isaac for five years over some long-forgotten peccadillo or slight, unintentional or otherwise. Isaac was understandably perplexed when, following his parents’ unexpected deaths during the COVID-19 epidemic—before the vaccines that may have spared their lives were available—he discovered that they had named him executor of their estate.

Isaac’s twin brother Paul had died in the War in Afghanistan, and a drunk driver had killed his brother Shane in a car wreck when Shane was just 18. Then, his sister Betty succumbed to a flareup of lupus, and Isaac became the last survivor of a lineage that traced itself all the way back to the verdant highlands of Ireland.

Clayton and his wife, Abigail, had worked at a Ford plant after Clayton returned from his tour of duty in Vietnam, where he earned a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star Medal. When the industrial economy collapsed in the Rust Belt states, the couple weathered that storm like most had, through stubborn force of will and ornery contrariness to dying. After Isaac and Paul were born, Clayton moved his family to a 10-acre farm that clung to the side of a mountain, where he built a house perched on a steep knoll.

Thunderstorms often washed the loose gravel down the driveway, leaving the surface open to erosion unless it was not laboriously carried back up to the level top to await the next washout. Clayton exercised his patriarchal authority to assign Isaac, Paul and Shane the task of restoring order to the driveway while he was at work driving a bulldozer to clear logging roads through the forests and dig farm ponds and basements. At first, the boys felt important because they were contributing to their family’s needs. The physical labor gave them lanky athletic physiques. During their teen years, however, Isaac grew to resent his indentured servitude. He particularly hated to do what was a Sisyphean task of carrying the rock up a hill only to see it tumble down again.

When Paul was killed in Afghanistan, Isaac came home to bury his brother and comfort his parents and siblings. Isaac had begun to see the chore of hauling gravel up the hill as a metaphor for both the Vietnam War and the War in Afghanistan, wars that could not be won, only abandoned. After Paul’s burial, Isaac and Clayton’s fiery disagreement ended only when Isaac fumed out of the house, vowing never to return.

Still, blood is blood, and Isaac worried about his parents when the grim reaper of the COVID pandemic began to harvest its mostly elderly victims. He knew Clayton’s intransigence would keep him from reconciliation, but by the time he had decided to visit to

make amends, Clayton and Abigail had died a day apart. When he returned home to close out the affairs of the estate, Isaac saw that Clayton had poured a concrete driveway over the gravel road. At the top of the driveway the initials “WD” were etched into the concrete. After the funeral, he met with his dad’s lawyer to settle the accounts. They set up an estate sale on Sept. 21.

The crowd gathered at 9 to bid on and buy the household chattel. Isaac was taken aback when he saw a handsome young Black man purchase the entire contents of Abigail’s kitchen. Curious at the stranger’s offer, Isaac introduced himself. “Hi, I’m Isaac, the Kellys’ son,” he said. “Mom cooked lots of great meals using those pots and pans.”

The man replied, “You’re just the man I need to talk to. I’m Joe, Willie Duncan’s son. I have something to give you from my dad.”

He pulled a crumpled, yellowed envelope with Clayton’s name on it from his jacket pocket. “Let me tell you the backstory,” Joe said. “My dad owned a concrete business. About four years ago, your dad called him about pouring this concrete driveway for him. Dad, my brother Josh, and I drove down and began to build the forms and pour the first sections. We worked until noon, and your dad came out and invited us to dinner. Dad was oldfashioned and had never been invited to break bread with a white family, so he respectfully declined. I saw your dad’s face darken. Then he said, ‘Look, my wife has spent all morning cooking a big dinner to feed you fellers. Now get in there and eat, like I said.’ ”

Joe smiled. “We saw there was no need to argue,” he said. “Your mother cooked us a great dinner of pork chops, mashed potatoes, green beans and coconut cream pie with black coffee. Finest meal I ever had. When I heard about this estate sale, I was determined to buy all the pots and pans your mom used to fix that dinner for us because it meant so much to us to be treated like people.

“Clayton paid us after we finished the driveway. Dad drew his initials—‘WD’—into the concrete, and we went home. All my dad could talk about was how a white man had invited us to dinner for the best meal he ever had. My mother told him that he had to write a thank-you note. He was supposed to mail this letter, but I guess he forgot where he put it. I found it last week stuck in his Bible and decided ‘better late than never,’ so here it is.”

“That’s very kind of you to remember,” Isaac said. “I’m sure Dad would appreciate it.”

Joe blushed. “Well, I actually wrote the letter,” he confessed. “Dad couldn’t read or write anything other than his name. I hope you understand.”

Isaac smiled and clasped Joe’s right hand in his and softly squeezed his left shoulder. “I understand,” he said. “My dad couldn’t read or write anything but his name either, but that doesn’t matter. Sometimes, words just get in the way, don’t they?”

28 KENTUCKY MONTHLY FEBRUARY 2023

Letter From Fallujah

JOHN E. CAMPBELL, LEXINGTON

Mama is showing me the latest letter from my brother, the way she always does. As she reads it a second or maybe third time, it quivers in her hand. Post-stroke palsy.

I can see Carbrook Manor personnel in pastel scrub suits buzzing around in the background. There is the occasional flash of a white lab coat. Residents lean on aluminum walkers or slump in wheelchairs.

Since COVID arrived, these Zoom sessions are the only means of face-to-face interaction for us: Mama in Florida, me in Louisville.

“Your brother wrote to me again,” Mama says, pride and concern in her tone. “He wrote from Fala… Falu…”

“Fallujah,” I say for her.

“Why is he still there?” she asks. “The TV says all our boys came home from Iraq.”

“He is part of the peacekeeping group,” I remind her.

“I want him to come home,” she says, a little peevish now. I am losing her. “He should be here for Christmas.”

I do not remind her that Christmas was three weeks ago.

Her mood shifts, and she looks away from the screen. “I don’t think I have much time left, and sometimes I can’t remember his face.”

“Oh, Mama, you’ll never forget Adam’s face.”

She pauses, looks at the letter, and then says, “Your brother wrote to me again. He wrote from Faloo… Fallojj…”

“Fallujah, Mama,” I say gently.

“Why is he still there?”

After 20 minutes and another read-through of the letter, the Zoom session ends, and we blow kisses to each other.

I exit Zoom, open a Word document and begin typing:

“Dear Mama, it is 105 degrees in Fallujah today, and my squad and I just got back from patrol.”

kentuckymonthly.com 29

fiction

The Quick Brown Fox That Catapulted Me to Typing Superstar

MARIE MITCHELL, RICHMOND

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. Do you recognize that sentence? It’s taught in Typing 101 because it uses every letter of the alphabet.

I grudgingly took typing my junior year of high school (1970-71) because my teachers didn’t consider me college material. I was smart enough. Just not motivated. So, without consulting me about my future, I was placed on the secretarial track.

My typing teacher was built like a linebacker, barked instructions like a drill sergeant, and sounded like Julia Child. Intimidating. I decided to humor her.

Each desk had a manual typewriter. You had to firmly punch the keys for a letter to strike the paper. Quite a workout. The keys operated separately, so if you pressed too many too quickly, they’d jam up. You’d have to stop to untangle them. And end up with inky fingers.

We weren’t allowed to peek at the keyboard. So, we memorized where all the vowels, consonants, numbers and punctuation marks were located.

This was back when we used all of our fingers—not just our thumbs.

In our low-tech world, when we came to the end of a line, we reached over and pumped the carriage return lever to advance to the next line. Type. Zing. Type. Zing— in a crazy rhythm.

We were expected to type fast. And flawlessly. Long fingernails were forbidden. They could sabotage our efficiency. No problem. I was a compulsive nail biter.

If we did make a mistake, we started over with a clean sheet of paper, unless it was a minor “oops.” Then, we could apply “Wite-Out” to make it disappear. It was messy but mostly effective.

Our spell checker was a thick Webster’s Dictionary.

I practiced my brown fox sentence tirelessly and secretly wished the lazy dog would nip the fox’s nimble toes as it jumped over him, just for some variety.

My perseverance eventually was rewarded by my scoring the best speed record in class—65 words per minute. The average was 40, not that I’m bragging. Still, this impressive feat seemed futile, since I didn’t want to work in a 9-to-5 office.

Shockingly, after some twists and turns in my life, I went to college, earned two degrees in communication, and became a broadcast journalist. Guess what skill has been invaluable throughout that journey?

Typing.

Typing assignments. Term papers. And newscasts.

In my career, my agile fingers flew over the keyboard as I banged out stories on impossible deadlines. Fortunately, I didn’t have to spell every word correctly—just phonetically, so the newscaster could recognize it.

My early newsrooms in Kentucky provided only manual typewriters. No problem for a veteran like me whose dexterous fingers could still pound away on those keys with Herculean strength and endurance.

Later, we added Selectrics, which responded to a gentler touch. Out of habit, I continued to press down hard on the keys, like I was whacking a mole with my bare hands. The letters were on a single rotating ball, which avoided those annoying key jams. The Selectrics also had an automatic carriage return and built-in correction tape. They spoiled us.

Next up: computers. My hero. And my nemesis. They simplified—and complicated—my life with their impressive time-saving features and exasperating glitches at the most inconvenient times. Still, we forged a working relationship that got the job done.

If my typing teacher were still around, I’d salute her. I should also thank that quick brown fox and its legendary jump that made me such a typing superstar.

30 KENTUCKY MONTHLY FEBRUARY 2023

nonfiction

On Returning Home

What can I tell you?

The Scottish landscape changes with the rain and sun and mist Clouds gather in white and grey melancholy moods

filling the taller than this Kentucky sky

The names of villages are not easy on the tongue like the landscape, vowels and consonants wind through mist and merge in unfamiliar realms

On the River Clyde, gulls cackle like crones drunk on too much ale “A pint is never enough!” one shouts and cackles again while grey feathers float to the cobblestone below.

Come, sit with me by the window

We’ll watch the rabbits fat and round, gather on the old Abbey grounds and wander into the monk’s graveyard to quietly nibble the velvet green moss on Brother Ignatius’ grave

Beyond the graves

The waters of Loch Ness are cold and black stained from rain-washed peat rolling off mountains separated an ice age ago

Both Scottish Highlands and Appalachians exist here in slip fault fashion

and genetic memory swims deep

Mr. Weaver

J.M. HELM CAMPBELLSVILLE

There’s a spider in my window

We visit every day

He always seems so busy

He has no time for play

I call him Mr. Weaver

He seems to like that name

He lives within my window

And I’m so glad he came

He can tell when I am happy

And he knows when I feel sad

I tell him all my troubles

He helps me if he can

I think he has no family

Guess I’m his only friend

He’s too busy to be lonely

As he weaves and spins again

I often bring a present

A tasty cricket or a fly

He never fails to thank me

When it’s time to say goodbye

Some might think it’s strange

To have a spider for a friend

But he’s always there for me

Though he has his web to tend

He doesn’t know how old he is

Spider years don’t count

He’s always working on his designs

He loves it there’s no doubt

I like to get real close

And look into his eyes

There’s so much there to see

A wonder old and wise

He wears a timepiece upon his back

It doesn’t keep the time

Others fear his hourglass

But he’s a friend of mine

He weaves and spins

And spins and weaves

A web of grand design

Perhaps someday I can weave

A life just half so fine

kentuckymonthly.com 31

ROSEMARIE WURTH-GRICE BOWLING GREEN

poetry

poetry

Culling

ROBERT L. PENICK LOUISVILLE

The sunflower stalks lie in the backyard lake carnage, like old beliefs. Syrup oozes from the rotten blossoms. Longer than a man, they waste in the sunlight, they atrophy, they burn.

Above them, the gnats hover. Each drawn to the sugar of death, sucking vitality from the sweetness of the flowers’ failure. They feast on cellulose, banqueting on what the sparrows and jaybirds disdain.

What is left of these stalks will be shredded and spread upon November ground. Time feeds on itself the way next year’s sunflowers will gather strength from these. The way darkness births twilight, and twilight, dawn.

black mold

KAITLYN MCCRACKEN WILMORE

it’s the scent of saturday cartoons and sunday sonatas and basement barred from little hands and little feet.

mahogany mildew lined walls of one-story ranch. the bones of faded jewel upholstery, torn seams, and piano keys, chipped and churning.

early weekend mornings to spilled and spoiled milk solidified to grainy carpet on little toes cringe with the creak of carpeted rot.

I

AMY LE ANN RICHARDSON OLIVE HILL

sunlight coating kitchen tiles coffee corroded china and shallow sliced countertops.

black speckled corners per vading and potent. sweet ambrosial incense emitting from walls absorbing through my skin like osmosis embracing my lungs like grandfather hugs tight and unyielding.

grime and gold stick and stone driveway rubbing eyes raw as we pull away.

32 KENTUCKY MONTHLY FEBRUARY 2023

poetry

poetry

poetry

As

Age I say my gray hairs are the light leaking out where I opened myself up to the world and allowed my mind to experience new ideas, so I radiate hope.

Whirly-gigs

on old route 40 where the road winds up the hills and curves kiss the rocky creek beds

a house sat in the nook an old wealthy valley of Oil Springs

two stories

hand carved wooden shutters a broad concrete porch with iron columns

I remember the tacky windchimes

Swinging and twisting in the wind wild colors and shells become a blur they were odd and out of place swaying about

he told me he got them from a woman who he called a peddler she sold for a sandwich

Pall Malls and gas for the road

he always felt the need to bring home whatever odds and ends were offered he’d say “they belong to someone they just needed to get where they are going maybe to find their person or waiting to be found”

I think he hung them there on his porch in case she ever came back around she’d feel like she was finding her way home

we called them whirly-gigs I wonder where she is now

kentuckymonthly.com 33 Wants to BUY YoUr gear We buy, sell and Trade Used mUsical iNsTrUmeNTs and equipment of all brands. mUsic go roUNd also oFFers aFFordaBle rePairs, seTUPs, resTriNgs aNd maiNTeNaNce. Wants to BUY YoUr gear We buy, sell and Trade Used mUsical iNsTrUmeNTs and equipment of all brands. mUsic go roUNd also oFFers aFFordaBle rePairs, seTUPs, resTriNgs aNd maiNTeNaNce 3640 S. Hurstbourne Pkwy. • Louisville, KY 40299 • 50 2 -4 9 5- 2199 musicgoroundlouisvilleky.com

poetry

COURTNEY MUSIC MOREHEAD

SPRING PREVIEW

Our Three Cows

Patsy was our business cow

Took her job seriously She gave her milk, and kept her place And never noticed me

Kitty was our hateful cow The meanest of the three She seemed to hate her job, her life And clearly hated me