one one.org

March 22 is World Water Day

bread

contents

City k r o Y nger u H New t gains A n o d Fl, r ti i 3 l , t a e o C er Stre v a e B 16 10004 Y N , k ew Yor N

In this Issue:

ter.

cen hewy

// 4read’s c n o i issf this as B M he’s 5 r e / s o u / a t c k O e thin dennal. Just in i s W e . Pr eas perso r M l r Dea ake our p We m g. in read

HARLEM

“It’s Welfare!” & Other Myths// 6 We debunk Food Stamp myths, one fallacy at a time.

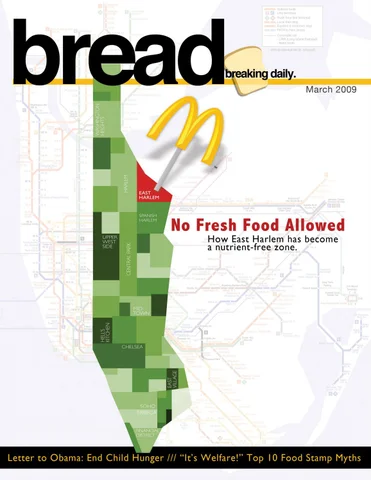

No Fresh Food Allowed

In a city where healthy food options abound, East Harlem is plagued by childhood obesity. Exactly how did East Harlem become a nutrient-free zone?

EAST HARLEM breaking daily

3

mission

B

Hungry No More.

y the early 1980s, hunger in New York City had become unbearably severe. Religious organizations and charitable agencies had long served their neighborhoods in relative isolation; despite the heroic efforts of these groups, their ad hoc approach had inherent limitations. Many began to realize that soup kitchens here and there could relieve, but not end, the problem of hunger in New York City. Community leaders from all five boroughs met in April 1983 and concluded that the best way to tackle hunger in the city was with a unified organization that helped emergency food providers and pushed for long-term solutions. In this spirit, the New York City Coalition Against Hunger was born. The Coalition’s original mission was to “coordinate the activities of the emergency food providers in the city so that issues can be identified, prioritized and addressed effectively.” Though its aims have expanded and evolved over the last two decades - for example, it has strengthened advocacy and legislative efforts and now provides national service participants to emergency food providers - food access for all New Yorkers has always remained the Coalition’s animating goal.

Do what you can to help save our city.

4

breaking daily

dear mr. president

H

Food For All.

Dear President Obama,

ello! We’re the New York City Coalition Against Hunger and we’re meeting for the very first time. gratulations on your election, we are looking forward to a successful next few years!

Con-

We want you to propose a bill that would: 1) Set a goal of cutting food insecurity among U.S. children in half by 2013 and ending it by 2015; 2) Provide the funding and the guidance necessary to enable most American elementary and secondary schools to provide every student with free school breakfasts (regardless of their family income) in the first-period classroom; 3) Provide the funding to enable every school in America to provide free lunches to all their students, regardless of family income (by making school meals universal in this way, the country can decrease government expenditures on paperwork now used to make income eligibility determinations and instead use that money improve the nutrition of children); 4) Increase reimbursements to school districts that provide healthier foods, particularly for districts buying from small local farmers; 5) Make the Women, Infants and Children (WIC) nutritional assistance program an entitlement available to any low-income parent or child who needs it and fund nutritional improvements in the WIC package; 6) Increase reimbursements for both government and non-profit agencies that sponsor after-school and summer meals for children; 7) Create the Beyond the Soup Kitchen Grants Program as proposed in the Anti-Hunger Empowerment Act of 2007 (HR206); and Do you hear us? Because we hear you.

Thanks, NYCCAH breaking daily

5

0 1 p o T s h t y M

Food

#1 – Food stamps are welfare.

False: Food stamps help keep people off welfare . The Food Stamps Program is known in public policy as a “work support,” meaning it is used by people looking for a job, or employed but not making enough to make ends meet. Because food stamps allow these people to maintain their employment, they ctually help people get off and keep off the welfare rolls.

#2 – The program costs NYC too much. False: The Food Stamps Program is a federal program – New York City only picks up a small part of the cost of administering the program, while the federal and state government picks up the rest.

#3 – Ok, the Food Stamps Program costs American taxpayers too much. False: The benefits of food stamps far outweigh their costs. Currently, paying for the Food Stamps Program takes about 1 cent of every federal budget dollar . In addition, the USDA has concluded that every dollar of emergency money spent on food stamps during a recession sparks $1.82 in local economic activity.

#4 – Food stamps are easy to obtain. False: Nationally, only 66 percent of people who are income-eligible for food stamps receive them . In New York City, roughly 700,000 people are eligible to receive food stamps but don’t. Studies conclude that the main reason eligible people don’t participate is the complex bureaucracy involved in applying,.

#5 – Most people who don’t receive food stamps simply don’t want help from the government. False: National opinion surveys conducted by the USDA have found that just 17 percent of eligible but non-participating families don’t participate in the program because they don’t want the help. Most are either unaware they are eligible, or don’t want to go through the onerous process of applying .

6

breaking daily

dStamps

insider

#6 – The Food Stamps Program is an inefficient bureaucracy. False: The Food Stamps Program has been praised by the Government Accountability Office and the current White House administration as a model of government efficiency. In 2002, the nationwide administration of the Food Stamps program amounted to only 11% of its program costs .

#7 – The Program is rife with fraud and abuse. False: Since the introduction of the EBT card system, fraud in the Food Stamps Program has reached an all-time low. Ninety-eight percent of food stamp benefits now go to households that are found eligible under very strict rules.

#8 – Fingerprinting applicants prevents fraud and abuse. False: There in no evidence that fingerprinting food stamps applicants reduces fraud. However, it does increase the cost of the program’s administration and is known to humiliate applicants, which is why only four states still have this regressive policy: California, Arizona, Texas and New York.

#9 – Food stamps benefits go to illegal immigrants. False: Illegal immigrants are not eligible to receive food stamps, and never have been; there are stringent processes to determine citizenship in the program. Legal immigrants are also not allowed to receive food stamps until they have been in the country for five years (with the exception of asylum cases and some other situations). Immigrants generally are far less likely than other groups to apply for food stamps, both because they fear jeopardizing their immigration status, and because the complex application process is doubly hard for those who do not speak English well.

#10 – Food stamps cause obesity and unhealthy eating habits. False: National studies of food stamps users have found that program participation has no significant effect, positive or negative, on the consumption of healthy foods. Several years of studies have produced no clear evidence that food stamps affect overeating or weight gain in either direction.

breaking daily

7

FreshFood Need Not Apply

NewYorkers live in what is arguably the richest city in the richest nation in the history of the world.Yet, New York remains a city divided in dramatic and contradictory ways. For instance, in the northern Manhattan neighborhood of East Harlem it is possible to see the city’s highest rate of obesity, as well as one of its highest incidences of hunger. Directly south of East Harlem lies the Upper East Side, where the rate of obesity is the lowest in the city, and hunger is almost nonexistent. How can one neighborhood demonstrate such striking incidences of supposedly opposing health problems, while their neighbors show little evidence of either? In a word, “control.” East Harlem residents go to work, school, and play like all other Americans, yet they lack basic control over many aspects of their lives. Like other New Yorkers, at any moment they may be faced with critical decisions concerning their families, homes and futures. But the environment of opportunities and choices available to them – simply because they live in a poor community – is dramatically starker than that available to their Upper East Side neighbors. In short, their choices are few. This paper is designed to unearth the dimensions of choice and control faced by East Harlem in its relationship with food. The lessons of scientific studies, national policy makers and advocates are put to the test, illustrating the alarming effects that an environment devoid of real choices can have on public health. This article will demonstrate how, compared to their neighbors on the Up-

per East Side, East Harlem residents lack proper access to nutritious food at almost every step on the economic ladder, from soup kitchens to supermarkets, from Food Stamps to farmer’s markets. This is not to say that nutritious food is unavailable in East Harlem – the neighborhood is far from what experts call a “food desert.” But good food here is expensive, inconvenient and poorly marketed in comparison to the abundance of processed “junk” food sold on every corner and cooked to taste in almost every restaurant. It is this unbalanced mix of food choices – the mirror opposite of what may be found on the Upper East Side – that makes unhealthy food the default option for East Harlem, a neighborhood that can afford no better. How can East Harlem be both hungry and obese? The reason this sounds contradictory has more to do with our perception of the problem than reality on the ground. Not only do hunger and obesity exist side by side in East Harlem, sometimes they exist within the same family. Public dismissal of the duality of hunger and obesity stems from long-held conceptions about how each looks. The first time many young Americans came face-to-face with “hunger” was during the advent of televised pleas for the victims of mass starvation in countries like Ethiopia during the 1980s. These nations, wracked by severe drought as well as crushing national debt and currency devaluation, were portrayed in stark detail to spur public sympathy. Starvation of this sort has never happened in modern America. By contrast, “hunger” in America is a political term that has been used to focus attention on everything from starvation (of which there is frankly little) to food insecurity and malnutrition (of which there is a shameful amount). As Woody Guthrie supposedly observed, “Americans let you get awful hungry, but they never quite let you starve.” Likewise, our recent obsession with obesity rarely mentions how the condition actually looks.While many New Yorkers might assume obesity resembles a cartoonish figure like Fat Albert, obesity is a strict medical term derived not from appearance but from the bodymass index (BMI).This equation uses height, weight and

breaking daily

9

feature a standardizing factor to determine “obesity” and its close cousin “overweight”i. Because obesity is a technical term and hunger such a political one, neither is easy to identify on sight. So while the image of a hungry Ethiopian child and Fat Albert enjoying a slice of pizza together on the corner sounds absurd, hunger and obesity are this close in many communities.

obesity is being treated like a disease. Evidence abounds that obesity and its related conditions are more common in poor households, one-parent households, and among racial and gender groups that have a higher rate of poverty in the United States and Canada. Obesity is also closely associated with poverty around the world.Several political figures have used these studies as evidence that with obesity on the rise, hunger is no longer a

Americans, including 13 million children, lived in households that experienced food insecurity – that’s one in ten households. Hunger and Obesity Linked What is the nature of the relationship between hunger and obesity? Is there one? As far as your doctor’s concerned, both terms can be used to represent extremes of malnutrition: an intake of nutrients that, for reasons of quality or quantity, is not conducive to health. Hunger makes this condition outwardly apparent: a person’s lack of a healthy body is evidence of their lack of body-building nutrients, or undernutrition. Obesity can hide such undernutrition behind a façade of plenty. An obese person may actually look over-nourished, but their obesity is often the result of eating food that’s high in fat but low in nutrients. A person eating this kind of food may need to eat two or three times as much of it just to survive. At the end of the day, while they may or may not manage to be well nourished, they will certainly be obese. In this way hunger and obesity can be thought of as two sides of the same coin. A BMI between 25 and 30 is considered overweight; above 30, obese. The recent spike in obesity has been called an “epidemic” by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention(CDC) According to the CDC, approximately 65% of American adults are now overweight, and 31% are obese. At last count, 16% of children 19 and under were overweight. These numbers are more than double the rates recorded between 197619802, and are enough to worry anyone. sudden spread,

10

breaking daily

problem of America’s poor. Conservative commentators like Robert Rector have claimed that poverty-induced malnutrition is “virtually non-existent” in America, and that today’s poor children are actually “supernourished.” Some members of the media have agreed with Rector, arguing that the prevalence of obesity proves that hunger is no longer a serious problem, and is instead a sign of increased “prosperity.” But if obesity were a sign of prosperity, why would poor people be the most obese? Outside of the Beltway, there are few who would argue that hunger no longer haunts low-income Americans. In the latest national survey of soup kitchens and food pantries supplied by the Second Harvest food bank network, 75% of recipients households were found to earn less than 130% of the poverty levelii. Not surprisingly, these recipients, most of whom are hungry, also share many demographic characteristics with the obese: 62% of clients were found to be women; half were white, 34% black and 16.7% Latino. Half of all recipient families with children were single-parent households. Since this time, New York City numbers (which generally fall in line with national trends) have reported even more requests for emergency food18, 19. Between 1999 and 2003, the U.S. Census noted an increase in hunger and the broader term of “food insecurity” with each passing year. And in 2003, USDA officials

reported that 36 million WASHINGTON HEIGHTS

Americans, including 13 million children, lived in households that experienced food insecurity – that’s one in ten households. In the 1970s, Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz artificially lowered prices on fast-food staples like beef and high-fat palm oil. At the same time,

HARLEM

technology created new staples like high-fructose

62% of East EAST HARLEM

SPANISH HARLEM

Researchers in New Orleans recently discovered that fast-food restaurants there are geographically associated with low income – and in particular African-American – neighborhoods.

Harlem residents are obese or overweight. corn syrup to replace traditional ingredients. Restaurant chains combined these ingredients with marketing tricks like “value-sizing” to increase sales cheaply.

CENTRAL PARK

UPPER WEST SIDE

Easy access to fast food affects all Americans, not just the poor ones. But while there is no direct evidence that chain restaurants deliberately target low-income communities, there is no doubt that the convenience and “value” pricing of this food has been well received in low-income households.

HELL’S KITCHEN

MIDTOWN

It is estimated that the average American increased his/her daily food consumption by 200 calories between 1977 and 1995.32 Fast food restaurants contributed to the bulk of this trend.33 The USDA has called this trend towards eating out “the biggest challenge to those seeking to promote fruit and vegetable consumption.” LOWER They found that restaurant-goers EAST typically eat only 1 ¼ servings of SIDE vegetables and ½ serving of fruit in a typical restaurant meal – and half of those vegetables are French fries.

EAST VILLAGE

CHELSEA

Since this happened, food consumption away from home has exploded. In 1970, 25% of the average American’s food budget was spent in restaurants; in 2002, this number was 46%.30 Our money isn’t being spent on salads, either – in tlast 20 years, fast food has risen from 3% to 12% of our average caloric intake.

SOHO TRIBECA

FINANCIAL DISTRICT

breaking daily

11

break bread. share bread. our bread. your bread. our daily bread. until we meet again,