14 minute read

EDITOR’S NOTE

NONFICTION | Eric Liebetrau

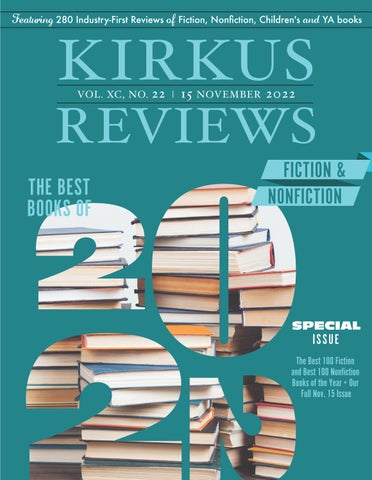

the best books of 2022

Choosing the best books of the year is always a pleasure and a challenge, but I am confident that there is something for every reader. Below are 10 books that demonstrate the diversity of the list across subject areas and genres. Dilla Time: The Life and Afterlife of the HipHop Producer Who Reinvented Rhythm by Dan Charnas (MCD/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Feb. 1): “An ambitious, dynamic biography of J Dilla, who may be the most influential hip-hop artist known by the least number of people.…[F]ully captures the subject’s ingenuity, originality, and musical genius.”

Woman: The American History of an Idea by Lillian Faderman (Yale Univ., March 15): “This highly readable, inclusive, and deeply researched book will appeal to scholars of women and gender studies as well as anyone seeking to understand the historical patterns that misogyny has etched across every era of American culture.”

Fine: A Comic About Gender by Rhea Ewing (Liveright/Norton, April 5): “Ewing presents a uniquely straightforward, unembellished amalgam of narrative and illustration, smoothly braided with their own personal journey. The instructive yet never heavy-handed narrative boldly shows how identity is intimately interpreted and how connections with others can fortify perceptions and perspectives.”

The Rise and Reign of the Mammals: A New History From the Shadow of the Dinosaurs to Us by Steve Brusatte (Mariner Books, June 7): “Throughout, the author employs lucid prose and generous illustrations to describe the explosion of mammal species that followed the disappearance of dinosaurs. A must for any list of the best popular science books of the year.” Nein, Nein, Nein!: One Man’s Tale of Depression, Psychic Torment, and a Bus Tour of the Holocaust by Jerry Stahl (Akashic, July 5): “Gonzo meets the Shoah in this wildly irreverent—and brilliant—tour of Holocaust tourism.…Stahl knows his Holocaust history…but he was also prepared to be surprised.…A vivid, potent, decidedly idiosyncratic addition to the literature of genocide.” Imagine a City: A Pilot’s Journey Across the Urban World by Mark Vanhoenacker (Knopf, July 5): “Philosophically rich without being ponderous, belonging on the same shelf as books by Saint-Exupéry, Markham, and Langewiesche, Vanhoenacker’s book is unfailingly interesting, full of empathetic details on faraway places and lives. It’s an absolute pleasure for any world citizen.”

Asian American Histories of the United States by Catherine Ceniza Choy (Beacon Press, Aug. 2): “An impressive new work about how major moments in Asian American history continue to influence the modern world.…An empathetic and detailed recounting of Asian American histories rarely found in textbooks.”

The Abyss: Nuclear Crisis Cuba 1962 by Max Hastings (Harper/HarperCollins, Oct. 18): “In his long, distinguished career, Hastings has masterfully covered both world wars, the Korean War, and Vietnam. In his latest, he thoroughly explores a fraught set of circumstances that almost led to World War III.…The definitive account.” The Song of the Cell: An Exploration of Medicine and the New Human by Siddhartha Mukherjee (Scribner, Oct. 25): “In his latest, [Mukherjee] punctuates his scientific explanations with touching, illustrative stories of people coping with cell-based illnesses, tracking how the knowledge gleaned from those cases contributed to further scientific advancement.…Another outstanding addition to the author’s oeuvre.”

Requiem for the Massacre: A Black History on the Conflict, Hope, and Fallout of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre by RJ Young (Counterpoint, Nov. 1): “Tulsa native Young…offers an ambitious, forceful continuance of his debut memoir, Let It Bang, focused on his development as a consciously Black writer while dogged by the massacre’s uneasy centennial.…An arresting account of Black ambition and endurance from an important new voice in narrative nonfiction.”

Eric Liebetrau is the nonfiction and managing editor.

strangers to ourselves

STRANGERS TO OURSELVES Unsettled Minds and the Stories That Make Us

Aviv, Rachel Farrar, Straus and Giroux (288 pp.) $28.00 | Sept. 13, 2022 978-0-374-60084-6

A perceptive and intelligent work about mental illness from the New Yorker staff writer.

In her debut, Aviv illuminates the shortcomings of modern psychiatry through four profiles of people whose states of being are ill-defined by current medical practice—particularly by those diagnoses laid out in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Throughout, the author interweaves these vivid profiles with her own experiences. When she was 6, in the wake of her parents’ divorce, Aviv was diagnosed with anorexia despite her abiding sense that that label was inaccurate. Later, the author writes about taking Lexapro. “To some degree, Lexapro had been a social drug, a collective experience,” she writes. “After a sense of uncanny flourishing for several months, my friends and I began wondering if we should quit.” Aviv applies her signature conscientiousness and probing intellect to every section of this eye-opening book. Her profiles are memorable and empathetic: a once-successful American physician who sued the psychiatric hospital where he was treated; Bapu, an Indian woman whose intense devotion to a mystical branch of Hinduism was classified against her will as mental illness; Naomi, a young Black mother whose sense of personal and political oppression cannot be disentangled from her psychosis; and Laura, a privileged Harvard graduate and model patient whose diagnosis shifted over the years from bipolar disorder to borderline personality disorder. Aviv treats her subjects with both scholarly interest and genuine compassion, particularly in the case of Naomi, who was incarcerated for killing one of her twin sons. In the epilogue, the author revisits her childhood hospitalization for anorexia and chronicles the friendship she cultivated with a girl named Hava. They shared some biographical similarities, and the author recalls how she wanted to be just like Hava. However, for Aviv, her childhood disorder was merely a blip; for Hava, her illness became a lifelong “career.”

A moving, meticulously researched, elegantly constructed work of nonfiction.

LINEA NIGRA An Essay on Pregnancy and Earthquakes

Barrera, Jazmina Trans. by Christina MacSweeney Two Lines Press (184 pp.) $21.95 | May 3, 2022 978-1-949641-30-1

A Mexican writer describes her pregnancy and the first months of her son’s life.

When Barrera first found out she was pregnant with her son, Silvestre, her husband suggested that she keep a pregnancy diary. Although she thought the idea of a pregnancy diary was “a little hackneyed,” she admitted that she was writing about her experience, albeit mostly in fragments. As she was adjusting to her changing body, Barrera and her family lived through an earthquake that destroyed the home of the patron who owned a collection of Barrera’s mother’s paintings. The author intertwines her experiences of pregnancy and motherhood—from labor and delivery to breastfeeding to discovering her doctor’s dishonesty—with a catalog of the condition of her mother’s paintings. Throughout the narrative, Barrera includes historical anecdotes and quotes from other women who have written about motherhood, childbirth, and pregnancy—from Mary Shelley and Natalia Ginzburg to Rivka Galchen and Maggie Nelson—and she argues that pregnancy is a fundamentally literary experience. “Pregnancy is transformation in time, it’s a retrospective account and—whether you like it not—there’s a plot, a story,” she writes. At the same time, she laments the fact that women are warned that having children signals the end of their literary careers. Here, she quotes Ursula K. Le Guin: Women “have been told that they ought not to try to be both a mother and a writer because both the kids and the books will pay—because it can’t be done—because it is unnatural.” The story ends in the early months of Silvestre’s life, which coincided with her mother’s treatment for ovarian cancer; this leads the author to examine the cyclical nature of motherhood. Barrera communicates her trenchant observations in gorgeous, highly efficient prose that sharply reflects the fragmented reality of pregnancy and early parenthood. Rather than adhering to a traditional narrative structure, the author follows her trains of thought wherever they take her, and readers will be happy to tag along.

A uniquely lyrical account of early motherhood.

special issue: best books of 2022

RUSSIA Revolution and Civil War, 1917-1921

Beevor, Antony Viking (592 pp.) $35.00 | Sept. 20, 2022 978-0-593-49387-8

The acclaimed British historian tackles the Russian civil war. Despite current events, Russia is not the colossus that frightened other great powers during much of the 20th century. Although its revolution is no longer a scholarly obsession, Beevor, the winner of the Samuel Johnson and Wolfson prizes, among others, masterfully recounts the violent events that seemed to change everything. When Russia declared war on Germany in 1914, it fielded the identical titanic but shambling army defeated by Japan in 1905, overseen by the same autocratic but dimwitted Czar Nicholas II and a dysfunctional civil government. Sustained by grit and Allied aid, it held together for nearly three years despite catastrophic losses. However, by March 1917, increasing desertion, indiscipline, and violence against officers combined with widespread civilian suffering persuaded the still clueless czar to abdicate. Beevor’s account of what followed is both authoritative and disheartening. No one could correct Russia’s crumbling infrastructure. Hungry city dwellers blamed the new leaders, and crime and violence flourished. Their worst decision was to continue the war, which increased insubordination at the front and perhaps even more so behind the lines. Lenin arrived in April to command the small Bolshevik Party, which grew and ultimately seized power that October. Historians have long stopped portraying him as the good guy in contrast to Stalin and agree that he succeeded as all tyrants succeed: murderous ruthlessness, crushing rivals, and incessantly repeating promises that appealed to his supporters (“all power to the Soviets,” “peace to the peasants”) and then not keeping them. This is a vivid description of a revolution that featured as much mass murder as military action. Readers know the outcome, but the Red triumph was not universal. A few Baltic states won independence, and in the final and perhaps largest campaign, Polish forces routed the Red Army. Always a meticulous researcher, Beevor has done his homework in an era when everyone recorded their thoughts (even the czar kept a diary), delivering a detailed yet unedifying story through the eyes of many participants.

A definitive account.

NORMAL FAMILY On Truth, Love, and How I Met My 35 Siblings

Bilton, Chrysta Little, Brown (288 pp.) $29.00 | July 12, 2022 978-0-316-53654-7

An entertaining memoir about a uniquely dysfunctional family. In her debut memoir, Bilton tells two remarkable stories. One is the chronicle of her wildly unconventional childhood as the daughter of a woman described by a friend, without much exaggeration, as “one of the great characters of the Western world.” Growing up “in Beverly Hills in the 1950s in a highsociety family—the prized granddaughter of a former governor of California…and the daughter of a prominent judge in Los Angeles,” Debra Olson was many things: an Eastern spiritualist; an out lesbian in homophobic times; a master saleswoman, making and losing millions in pyramid schemes; a friend of many celebrities; Ross Perot’s “civil rights coordinator”; and a hedonist and sometime addict who yearned “to overdose on everything, especially life.” Though her daughters were by far the most important part of her life, the girls’ childhoods were marked by instability and loss, with both their father, Jeffrey, and many other second “mothers” coming and going on a regular basis. Bilton’s warts-and-all depiction is sometimes hilarious, sometimes horrifying, always grounded in extraordinary forgiveness and resilience. The second story is the tale of Donor 150, who was by far the most popular option for those purchasing sperm at the California Cryobank in Century City, recommended constantly by the nurses and the doctor who ran the place. In 2005, over a decade after his retirement from the sperm donation business, Jeffrey saw a headline on the front page of the New York Times: “HELLO, I’M YOUR SISTER. OUR FATHER IS DONOR 150.” The author was a sophomore in college at the time, and it would be another two years before she became aware of the situation. By then, there were documentaries, magazine articles, a Facebook group, and ever more popular DNA testing. By that time, as she would soon learn, she was dating her own brother.

A wholly absorbing page-turner that everyone will want to read. You should probably buy two.

BIRDS AND US A 12,000-Year History From Cave Art to Conservation

Birkhead, Tim Princeton Univ. (496 pp.) $35.00 | Aug. 9, 2022 978-0-691-23992-7

A study of birds as inspiration, enlightenment, and food. Melding science, natural history, memoir, and travelogue, ornithologist Birkhead offers a commodious

in love

history of humans’ connection to birds, from prehistoric times to the current burgeoning interest in bird-watching. He begins in southern Spain, where depictions of more than 200 birds were discovered in Neolithic caves. This “birthplace of bird study” raises the question of the artists’ motivation: Do the images represent totemism, suggesting that birds were worshipped? Did the artists pay homage to birds prized for food? Did the images serve as a kind of field guide? In ancient Egypt, mummified birds were found in catacombs, preserved as food, pets for the deceased, or votive offerings. Birkhead examines early interest in investigating birds (by Aristotle and Pliny the Elder, for example); falconry as pastime, an “expensive, time-consuming” indulgence of aristocrats; and the medieval veneration of birds as “hovering midway between heaven and earth, half angels, half animals,” which can be deduced from the appearance of birds in religious paintings. As prey—sometimes for food, sometimes for sport—bird populations often have been decimated. Tudor England fostered an “unthinking persecution of wildlife” that included birds seen as “vermin.” In the late 1950s, Mao Zedong set off mass killings of sparrows, blamed for stealing grain. The 17th century saw a marked interest in scientific investigation, resulting in a proliferation of description, collection, and illustration of birds. Victorians paradoxically cherished birds, enjoying a vogue for caged songbirds but also for amassing specimens of birds, skins, and eggs. From acorn woodpeckers to zebra finches, Birkhead examines bird habitat, behavior, cultural meaning, and physiology in species around the world. He creates engaging portraits of the often eccentric individuals involved in bird investigations and reports on some exotic uses of birds for food—flamingos’ fatty tongues, for example, roast peacock, and fattened herons. This beautifully produced volume is replete with drawings, photographs, maps, and vivid color plates.

A fascinating, authoritative avian history.

THE MOSQUITO BOWL A Game of Life and Death in World War II

Bissinger, Buzz Harper/HarperCollins (480 pp.) $32.50 | Sept. 13, 2022 978-0-06-287992-9

A uniquely focused World War II history interweaving military heroics and college football. Many books describe the consequential Battle of Okinawa in 1945, but this one deserves serious attention. Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Bissinger, author of Friday Night Lights, makes good use of his sports expertise to deliver a vivid portrait of college football before and during WWII, when it was a national obsession far more popular then professional leagues. He recounts the lives and families of a group of outstanding players who made their marks before joining the Marines to endure brutal training followed by a series of island battles culminating in Okinawa, which many did not survive. The author, whose father served at Okinawa, offers illuminating diversions into Marine history, the birth of amphibious tactics between the wars (they did not exist before), the course of the Pacific war, and the often unedifying politics that guided its course. To readers expecting another paean to the Greatest Generation, Bissinger delivers several painful jolts. Often racist but ordered to accept Black recruits, Marine leaders made sure they were segregated and treated poorly. Though many of the athletes yearned to serve, some took advantage of a notorious draft-dodging institution: West Point. Eagerly welcomed by its coaching staff, which fielded the best Army teams in its history, they played throughout the war and then deliberately flunked out (thus avoiding compulsory service) in order to join the NFL. In December 1944 on Guadalcanal (conquered two years earlier), two bored Marine regiments suffered and trained for the upcoming invasion. Between them, they contained 64 former football players. Inevitably, they chose sides and played a bruising, long-remembered game, dubbed the Mosquito Bowl. In the final third of the book, Bissinger provides a capable account of the battle, a brutal slog led by an inexperienced general who vastly underestimated his job. The author emphasizes the experience and tenacity of his subjects, most of whom were among the 15 killed.

College football and World War II: not an obvious combination, but Bissinger handles it brilliantly.

IN LOVE A Memoir of Love and Loss

Bloom, Amy Random House (240 pp.) $26.00 | March 8, 2022 978-0-593-24394-7

A beloved fiction writer shares the story of her husband’s assisted suicide after being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

Readers will be locked into this gorgeously written memoir out of profound sympathy for the decision Bloom’s 65-year-old husband made upon learning of his condition. A man who absolutely loved life, Brian immediately asked for help planning an early exit. By that time, the couple had for several years endured the depredations of his failing cognition without knowing why. Bloom describes this period with regret, longing, and her trademark mordant humor: “He has gotten me some really ugly jewelry in the last three years, things that are so far from my taste that, if he were a different man, I’d think he was keeping a seventiesboho, broke-ass mistress in Westville and gave me the enameled copper earrings and bangle he bought for her, by mistake.” After researching what the future might hold, they sought the services of Dignitas, a Swiss organization supporting “accompanied suicide.” The application process was complex. As one of Bloom’s friends joked, “It’s like you do everything you possibly can to get your kid into Harvard and when you do, they kill him.” Along with this black humor comes plenty of despair. Sadness and tears