FEATURING 296 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children’s, and YA Books

FEATURING 296 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children’s, and YA Books

The bestselling novelist shows readers a good time in The Note

FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK

HAPPY NEW YEAR! Now fasten your seat belts: Given the dire state of our world at present, 2025 promises to be a bumpy ride. In such ominous times, you’d expect readers to seek out escapist fare—cozy mysteries, breezy rom-coms, books with magic and dragons galore.

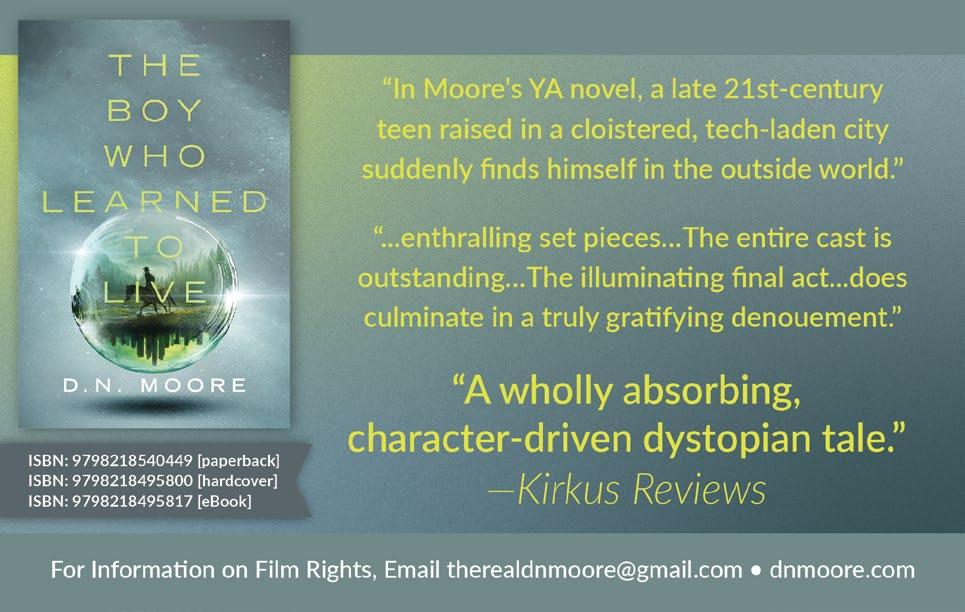

But booksellers found the opposite trend in effect in the days immediately following the U.S. presidential election—the results of which, let’s face it, depressed roughly half the electorate. As Kirkus and many other outlets reported in November, consumers were seeking out dystopian fiction. The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood’s prescient 1985 novel of life in a theocratic regime where women are second-class citizens forced to bear children, was the No. 2 seller on Amazon, while

George Orwell’s Animal Farm and Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451—classic depictions of totalitarianism—also saw dramatic spikes in sales.

Sometimes you just have to embrace the darkness, I guess. During those uncertain postelection weeks, I picked up an advance reading copy of Ali Smith’s forthcoming novel. In her acclaimed Seasonal Quartet, the Scottish-born author offered a real-time snapshot of the United Kingdom in the aftermath of the Brexit vote, written rapidly as events were unfolding. It was politically engaged writing— Summer won the Orwell Prize for political fiction—set firmly in our current-day society.

Now, in Gliff (Pantheon, Feb. 4), Smith imagines a future (not so distant?)

Frequently Asked Questions: www.kirkusreviews.com/about/faq

Fully Booked Podcast: www.kirkusreviews.com/podcast/

Advertising Opportunities: www.kirkusreviews.com/book-marketing

Submission Guidelines: www.kirkusreviews.com/about/publisher-submission-guidelines

Subscriptions: www.kirkusreviews.com/magazine/subscription

Newsletters: www.kirkusreviews.com

For customer service or subscription questions, please call 1-800-316-9361

where the government compiles vast troves of data on its citizens and renders certain people “unverified,” literally painting red lines around their homes. We encounter this world through the eyes of tween siblings whose existence becomes precarious after their mother departs to work in an “art hotel” and her boyfriend abandons them. The reader, like young Rose and Briar, is trying to decipher the rules and meanings of this inscrutable society. Our starred review calls it a “dark vision brightened by the engaging craft of an inventive writer.”

Gliff, while often philosophical and high-minded (one thematic strain has to do with the slipperiness of language and meaning in an authoritarian state), will satisfy readers seeking out dystopian scenarios. Here are two more books, also out soon, that take readers to the dark side.

Darkmotherland by Samrat Upadhyay (Soho, Jan. 7): This epic new novel, by the Nepalese American author of Mad Country and other books, imagines a fictional

Himalayan nation ruled by an autocrat known as PM Papa. After a devastating earthquake destroys half the country, a state of emergency is declared—and “all political activities [are] immediately banned.” Our starred review likens the book to “Pynchon by way of Rushdie… Dizzyingly complex and dazzlingly written, full of rewards and arch humor for the patient reader.”

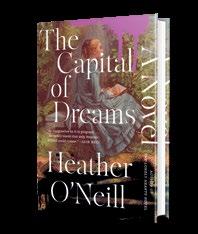

The Capital of Dreams by Heather O’Neill (Harper Perennial/HarperCollins, Jan. 7): In the fictional country of Elysia, young Sofia Bottom-Zier, daughter of a leading intellectual, is sent on a “Children’s Train” to the countryside after the invading “Enemy” promises children safe passage out of the besieged capital. But are they actually being sent to their executions? In a starred review, our critic praises this “fairy tale–adjacent bildungsroman” as “heartbreaking, magical, and real.”

Co-Chairman

HERBERT SIMON

Publisher & CEO

MEG LABORDE KUEHN mkuehn@kirkus.com

Chief Marketing Officer

SARAH KALINA skalina@kirkus.com

Publisher Advertising & Promotions

RACHEL WEASE rwease@kirkus.com

Indie Advertising & Promotions

AMY BAIRD abaird@kirkus.com

Author Consultant RY PICKARD rpickard@kirkus.com

Lead Designer KY NOVAK knovak@kirkus.com

Magazine Compositor

NIKKI RICHARDSON nrichardson@kirkus.com

Kirkus Editorial Senior Production Editor ROBIN O’DELL rodell@kirkus.com

Kirkus Editorial Senior Production Editor

MARINNA CASTILLEJA mcastilleja@kirkus.com

Kirkus Editorial Production Editor

ASHLEY LITTLE alittle@kirkus.com

Copy Editors

ELIZABETH J. ASBORNO

LORENA CAMPES

NANCY MANDEL BILL SIEVER

Contributing Writers

GREGORY MCNAMEE

MICHAEL SCHAUB

Co-Chairman

MARC WINKELMAN

Editor-in-Chief TOM BEER tbeer@kirkus.com

President of Kirkus Indie

CHAYA SCHECHNER cschechner@kirkus.com

Fiction Editor

LAURIE MUCHNICK lmuchnick@kirkus.com

Nonfiction Editor JOHN McMURTRIE jmcmurtrie@kirkus.com

Young Readers’ Editor

LAURA SIMEON lsimeon@kirkus.com

Young Readers’ Editor

MAHNAZ DAR mdar@kirkus.com

Editor at Large MEGAN LABRISE mlabrise@kirkus.com

Senior Indie Editor DAVID RAPP drapp@kirkus.com

Indie Editor ARTHUR SMITH asmith@kirkus.com

Editorial Assistant

NINA PALATTELLA npalattella@kirkus.com

Indie Editorial Assistant

DAN NOLAN dnolan@kirkus.com

Indie Editorial Assistant SASHA CARNEY scarney@kirkus.com

Mysteries Editor

THOMAS LEITCH

Contributors

Reina Luz Alegre, Autumn Allen, Paul Allen, Stephanie Anderson, Jenny Arch, Kent Armstrong, Mark Athitakis, Nada Bakri, Colette Bancroft, Audrey Barbakoff, Elizabeth Bird, Elissa Bongiorno, Hannah Bonner, Melissa Brinn, Jessica Hoptay Brown, Cliff Burke, Kevin Canfield, Catherine Cardno, Tobias Carroll, Sandie Angulo Chen, Amanda Chuong, Tamar Cimenian, K.W. Colyard, Emma Corngold, Kim Dare, Michael Deagler, Cathy DeCampli, Dave DeChristopher, Elise DeGuiseppi, Suji DeHart, Steve Donoghue, Elspeth Drayton, Eamon Drumm, Jacob Edwards, Lisa Elliott, Tanya Enberg, Chelsea Ennen, Kristen Evans, Joshua Farrington, Brooke Faulkner, Margherita Ferrante, Amy Seto Forrester, Mia Franz, Ayn Reyes Frazee, Jenna Friebel, Nivair H. Gabriel, Carol Goldman, Amy Goldschlager, Carla Michelle Gomez, Melinda Greenblatt, Vicky Gudelot, Tobi Haberstroh, Dakota Hall, Alec Harvey, Peter Heck, Lynne Heffley, Ralph Heibutzki, Loren Hinton, Zoe Holland, Yung Hsin, Abigail Hsu, Julie Hubble, Kathleen T. Isaacs, Kristen Jacobson, Wesley Jacques, Kerri Jarema, Ivan Kenneally, Colleen King, Katherine King, Stephanie Klose, Lyneea Kmail, Alexis Lacman, Megan Dowd Lambert, Christopher Lassen, Tom Lavoie, Judith Leitch, Donald Liebenson, Elsbeth Lindner, Coeur de Lion, Patricia Lothrop, Mikaela W. Luke, Wendy Lukehart, Kyle Lukoff, Leanne Ly, Joan Malewitz, Joe Maniscalco, Collin Marchiando, Emmett Marshall, J. Alejandro Mazariegos, Kirby McCurtis, Jeanne McDermott, Zoe McLaughlin, Carrigan Miller, J. Elizabeth Mills, Chintan Modi, Tara Mokhtari, Clayton Moore, Rebecca Moore, Andrea Moran, Rhett Morgan, Molly Muldoon, Jennifer Nabers, Christopher Navratil, Liza Nelson, Katrina Nye, Erin O’Brien, Tori Ann Ogawa, Mike Oppenheim, Emilia Packard, Megan K. Palmer, Derek Parker, Sarah Parker-Lee, Hal Patnott, Deb Paulson, Alea Perez, John Edward Peters, Jim Piechota, Christofer Pierson, Vicki Pietrus, William E. Pike, Shira Pilarski, Judy Quinn, Kristy Raffensberger, Jonah Raskin, Kristen Rasmussen, Matt Rauscher, Maggie Reagan, Caroline Reed, Stephanie Reents, Amy B. Reyes, Jasmine Riel, Amy Robinson, Lizzie Rogers, Elisa Rowe, Gia Ruiz, Lloyd Sachs, Bob Sanchez, Caitlin Savage, Meredith Schorr, E.F. Schraeder, Gretchen Schulz, Danielle Sigler, Leah Silvieus, Linda Simon, Margot E. Spangenberg, Allison Staley, Allie Stevens, Mathangi Subramanian, Jennifer Sweeney, Deborah Taylor, Eva Thaler-Sroussi, Bill Thompson, Renee Ting, Lenora Todaro, Bijal Vachharajani, Katie Vermilyea, Francesca Vultaggio, Sara Beth West, Paul Wilner, Kerry Winfrey, Marion Winik, Jean-Louise Zancanella, Natalie Zutter

WELCOME TO 2025, and get ready for some great books. If you’ve been waiting for a new novel from Alafair Burke—her last two were continuations of the work she did with the late Mary Higgins Clark, and she hasn’t published a solo thriller since Find Me in 2022—you’ll be excited to read The Note (Knopf, Jan. 7). Bonus: The book begins with a weekend in the Hamptons, so no matter where you are, you’ll be able to imagine you’re sitting on the beach—but surely you wouldn’t leave a note on the windshield of an annoying stranger’s car, accusing the owner of cheating on his companion. That’s what Kelsey Ellis does, though, and when the man is reported missing, she and her friends May Hanover and Lauren Berry come under suspicion. “Burke builds an intricate structure of secrets layered within secrets, revealed for maximum suspense,” according to our starred review. (Read an interview with Burke on p. 12.)

Ready for a story about the survivors of an apocalypse? In her earlier novels, Erika Swyler wrote about both mermaids and astronauts;

now, in We Lived on the Horizon (Atria, Jan. 14), she combines fantasy and science to create a far-future society that’s even more stratified than our own, with people known as Saints living in the lap of luxury while everyone else works endlessly to support them. When one of the Saints is killed, Saint Enita Malovia tries to figure out what it means. “Swyler achieves a seemingly impossible amount of sophisticated worldbuilding using an economy of vibrant, graceful prose,” according to our starred review.

Perhaps you’ve been eager to read Han Kang since she became the first South Korean winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature in October. Her latest novel, We Do Not Part (translated by e. yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris; Hogarth, Jan. 21), is a story of friendship and history. Kyungha, the narrator, lives near Seoul, and she gets a text one day from an old friend, Inseon, who’s in the hospital, asking her to travel to Jeju Island to take care of Inseon’s pet bird. Then there’s a snowstorm. “The quiet intricacy of the author’s prose glitters throughout, but nowhere is

this so evident as in her descriptions of the snow,” according to our starred review. “This is a mysterious book that resists easy interpretation, but it’s clearly addressing the violent legacies of the past.”

If you’re looking for a debut novel, consider A Gorgeous Excitement by Cynthia Weiner (Crown, Jan. 21). Set in New York during the summer of 1986, when the author was a teenager there herself, it’s inspired by the life of Jennifer Levin, the 18-yearold who was strangled in Central Park by Robert Chambers, a man she’d been dating, whom the tabloids dubbed “the Preppy Killer.” Weiner’s protagonist, Nina Jacobs, is getting ready to leave town for college, and she spends the summer temping by day and hanging out in a bar that doesn’t card underage patrons by night. With its “strong young characters and skin-crawling atmosphere created by creepy men, crimes in the news, porn shops, and overheated adolescent sexuality…this edgy coming-of-age novel succeeds on all counts.”

Laurie Muchnick is the fiction editor.

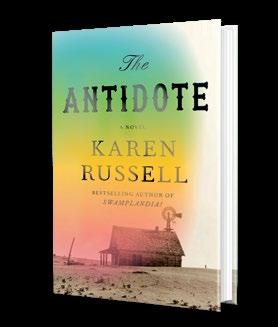

In the wake of the destructive Black Sunday dust storm in 1935, four outcasts dare to offer their dying town a radical vision of the future.

Antonina Rossi, an Italian immigrant and survivor of the Milford Home for Unwed Mothers, is the prairie witch of Uz, Nebraska. By falling into a trance, she relieves customers of memories they no longer want and deposits them in the vault of her subconscious. When the dust storm sweeps those memories clean away, Rossi recognizes her “bankruptcy” for what it really is: a mortal danger. Like most witches, Rossi is an outsider, and she throws her lot in with a band of fellow misfits. There’s Asphodel Oletsky, a teen basketball star and born hustler in love with her best friend; Harp

Oletsky, Dell’s shy bachelor uncle, whose farm miraculously survives the roiling clouds of dust; and Cleo Allfrey, a Black government photographer sent to document the crisis with a camera that somehow captures the past—and the possibilities of the future. Russell has always expertly woven the strange into depictions of the everyday, and her long-awaited second novel is no exception. Though the language here is looser and more conversational than in her past work, she still has a knack for capturing images in a deft turn of phrase—the flowers of a potted begonia have “small, blushing faces,” for instance. But what’s really on display here is Russell’s reckoning with America’s past and her hopeful appeals for its future. She juxtaposes the

immigration story of the Oletskys against the forced removal of Native Americans from the West and lets the catastrophe of the Dust Bowl resonate with the contemporary horrors of climate change. Characters struggle with their complicity in the American project of Native erasure and violence against vulnerable people, reinforced by the collective forgetting that

prairie witches enable. While the full picture of the novel takes time to develop, the final portrait is as unforgettable as the images Cleo Allfrey hangs on her darkroom line: A singular, haunting vision that fearlessly excavates the past and challenges the reader to face the future head-on. A storytelling tour de force that lives up to the promise of its name.

THE JACKAL’S MISTRESS

Austin, Emily | Atria (256 pp.) | $27.99

Jan. 28, 2025 | 9781668058145

Two small-town sisters have very different experiences of post–high school life.

Growing up in a conservative, remote small town named Drysdale, Margit and Sigrid could not have been more different and never called themselves friends. While Margit graduated from high school, Sigrid did not. Margit went on to college, majoring in literature, while Sigrid worked at Dollar Pal. Margit is straight and Sigrid is gay. Margit grew up trying to be perfect and control every outcome because of her parents’ vicious fights—both verbal and physical— whereas Sigrid lived in a dream world where her parents were swamp monsters that she had to hide from and she spent much of her time playing with toys in the basement or with her best friend, Greta. The sisters come together, though, when Sigrid tries to die by suicide. The book is divided into three sections: The first is made up of Sigrid’s 21 attempts at a suicide note; the second, labeled “The Truth,” is told from Margit’s point of view after she finds Sigrid; the third is Sigrid’s journal after she wakes up from a coma. The book covers uncomfortable topics in depth and often in an overly breezy manner. Margit and Sigrid are both far from reliable narrators, and with the many iterations of Sigrid’s suicide note and the dueling point-of-view sections, there’s a lot of repetition and different versioning of events, so it’s hard to track plot developments, characterization, and motivations.

A dark story of unhappiness, mental health struggles, and growing up with volatile parents.

Baker, Angelica | Flatiron Books (288 pp.)

$28.99 | Feb. 25, 2025 | 9781250345776

Six friends travel to Hawaii to celebrate their 30th birthdays and, after dodging imminent death, spend their time together drinking, bickering, reaching for one another, and investigating their years of interconnection.

Clare, Kyle, Renzo, Mac, Jessie, and Liam have known one another since seventh grade in L.A. They’ve fallen in and out of friendship and love with one another and have emerged as a (sometimes begrudgingly) inseparable unit. On this particular reunion in January 2018, they’ve gathered in Kyle’s parents’ second home on the island of Kaua‘i, planning to spend the week in full-on vacation mode. Then comes an emergency text advisory: “Ballistic missile threat inbound to Hawai‘i…This is not a drill.” After a few pages of watching the characters panic, we learn that the message was human error. The group feels its aftershocks long after that morning, though, and the anxiety it sows feeds the interpersonal reckonings that follow. Much of the richness in this novel is found in the conversations among the friends, which extend from their shared history and personal lives to politics, race, and class. Hawaii is a fitting backdrop for the more political conversations, but the relationship

between the group and the land is not as fully fleshed-out as the friends’ grudges and crushes. The main protagonist, Clare, spends much of the book reminiscing on years past and chewing over her writing career, marriage to her college sweetheart, and relationship with each member of the group. Baker beautifully expresses the pressures of growing older while not feeling older, as well as the comfort of being with people who knew you as an adolescent—when you were unformed and naive, as you might still feel from time to time. “When you’ve known people this long,” Clare thinks, “when you knew them in middle school, knew their mothers and their childhood bedrooms, you can always see the ghosts at their shoulders.” A delayed coming-of-age story that’s both perceptive and absorbing.

Bohjalian, Chris | Doubleday (336 pp.)

$29.00 | March 11, 2025 | 9780385547642

A gravely wounded Union soldier heals with the ministrations of a Southern woman. It’s 1864 in Virginia, and Union Captain Jonathan Weybridge loses his right leg and several fingers on the battlefield at Gilbert’s Ford. A fellow soldier stanches the bleeding by applying a tourniquet, but otherwise leaves him to die. Then, a formerly enslaved woman named Sally discovers him and brings him to the home of 24-year-old Libby Steadman She is a white woman whose husband, Peter, had freed the people enslaved at the gristmill he inherited and is now in a Yankee prison, if he’s even still alive. Sally and her husband, Joseph, now work at the gristmill, but the other freed slaves have long since skedaddled. Libby has a 12-year-old niece, Jubilee, who refers to Weybridge as a jackal, a not uncommon insult hurled at Union

soldiers. Weybridge’s health slowly returns while he frets about his wife in Vermont. Libby and her family come to recognize his human decency, that he’s more than simply a jackal or a “bluebelly.” Meanwhile, rumors circulate that Libby is harboring a wounded Yankee, and she and her family go to great lengths to hide him. She and the captain will quickly hang if discovered. She secretly enlists the help of a local doctor and part-time drunk whom she isn’t convinced she can trust, but she has no choice. Will Libby and the captain ever hear from their beloved spouses again? She refers to him as “someone…I kept alive at a price I could not afford.” Bohjalian’s inspiration for the novel comes from documented historical events—a Virginia woman really did save a Union soldier who’d hailed from Vermont—and the set-up has led to a masterful yarn. No one knows how close to each other the real people became, and there’s no evidence that the real Libby ever shot two Confederate soldiers dead with a Colt pistol or that a freedman (Joseph, in the story) killed a man who’d tried to rape her. Those and other details are a credit to the author’s imagination. If there is a nit to pick, it’s with a title that might misdirect readers’ expectations. It’s not wrong, but don’t expect anything steamy or licentious.

A compelling story about two people who long for their spouses in a time of war.

Kirkus Star

Saint of the Narrows Street

Boyle, William | Soho Crime (448 pp.)

$28.95 | Feb. 4, 2025 | 9781641296403

Smacking her abusive, low-life husband in the head with a cast-iron pan, a young Brooklyn mom sets off a chain of events that threatens her and her family, including her young son.

Risa Taverna is the essence of well-behaved (“she’s lived all tightened up”). But when her drunk husband, Sav, points a gun at her; her 8-month-old son, Fab; and her close sister, Giulia, she takes action. Tragically, Sav hits his head on a table on the way down and dies. With the help of Fab’s “Uncle Chooch,” who has long pined after Risa, the desperate sisters bury the body in upstate New York and tell everyone in their Italian neighborhood of Gravesend that Sav ran off to parts unknown. Everyone except Fab, who barely speaks, manages to lead a normal-ish life until years later when Sav’s wretched older brother, Roberto, shows up questioning Risa’s story (he will regret doing so). Years later, Father Tim, a young priest with money problems, tries to extort money from Risa to keep him from spreading rumors about Sav that he heard in a bar. And in the final section of this flowing epic, Fab, now an angry, delinquent teenager with gambling debts, goes off in search of the father he barely knew but is fast turning into. An established noir master, Boyle outdoes himself in crafting a novel of deep dimensions marked by intergenerational trauma, family strife, and failed religion (“the cardboard taste of a million communion wafers remained in his mouth”). It’s a page-turning performance with unforgettable scenes, including a nearly unbearable one in which Risa can’t help serving the blackmailing priest warmed up lasagna even as he’s threatening her. The names of the characters, including Jane the Stain, All Bad Allie, and Cyclone Archie, are worth the price of admission.

A great, gravely unsettling novel that welcomes repeated readings.

The Last Hamilton

Bregman, Jenn | Crooked Lane (288 pp.) $29.99 | Feb. 11, 2025 | 9781639109913

A Machiavellian plan to dominate the world’s gold reserves stretches all the way back to that guy from the Lin-Manuel Miranda musical. In Manhattan, a distraught young woman breaks into the Grange National Memorial, built by Alexander Hamilton, and frantically searches a piano for an invaluable item. Not finding it and feeling pursued, she jumps in front of a subway train to her death. The woman turns out to be newlywed Elizabeth Hamilton Walker, the last Hamilton of the title. Her middle-of-the-night text to BFF Sarah Brockman triggers a worried call from Sarah to Elizabeth’s husband, Ralph. The discovery of Elizabeth’s body and a dogged investigation by Det. Deborah Schwartz does little to assuage Sarah’s unease. The intrepid Sarah, who works at the Bank of Hoboken, remains at the center of the novel as it caroms around a handful of other characters. While she sifts through Elizabeth’s surprising documents, which warn of an ominous plot, her hapless coworker Pierce shares sensitive intelligence about gold reserves with his devious friend Timothy. Meanwhile, Schwartz tries to link a pair of broken eyeglasses to Elizabeth, and Viktor and Sergei and Dmitri and Yugov, a clutch of cartoonish thugs from Russian intelligence, plot a lot. The Hamilton premise of Bregman’s thriller is audacious and potentially explosive, but it feels grafted onto the tale, more a MacGuffin than a motor. The story sits in neutral for a long time, bouncing among the characters, before heating up. Readers will decide whether the disclosures live up to the foreshadowing.

An intricate thriller that simmers but rarely bubbles.

Bruce, Camilla | Del Rey (368 pp.) | $19.00 paper | Jan. 28, 2025 | 9780593724958

A fter adopting her nieces, a woman finds her life turned upside down by the ghosts of her past come back to haunt her—literally.

Clara Woods hated her brother in life. Now that he’s dead, killed on an anniversary quest to climb K2 with his wife, she finally has a way to get back at him: by using his daughters’ childcare allowance to fund her business venture, Clarabelle Diamonds. What Clara doesn’t know is that Ben’s children are special: 14-year-old Lily can see emotions like multicolored flames on other people’s bodies, and 9-year-old Violet can commune with spirits. But when this last ability causes Violet to inadvertently free the ghosts lingering on her aunt’s property, Clara, Lily, Violet, and Clara’s housekeeper, Dina, find themselves at the epicenter of a real-life haunting. The ghosts of Clara’s former employer, Cecilia Lawrence, who left her the house where they’re living; Clara’s missing husband, Timmy; and his mistress, Ellie, come untethered from their places around the home. Now unshackled and able to affect the material realm, they have one mission: to make Clara’s life a living hell. And unluckiest of all, a séance reveals that the only way to stop the haunting may be Clara’s own murder. In spite of subject matter consisting of axe murders and occult rituals, this is a light and lighthearted reading experience. The audience will crow to watch the deliciously awful Clara get her comeuppance, as her not-sofriendly ghosts do everything they can to make her even more miserable than she already is. Lily and Violet are capable narrators, and Violet’s plucky attitude makes her chapters a particular delight to read. Although Bruce’s latest offering will not appease readers looking for a terrifying haunted-house story, mystery and

thriller fans will find a lot to love in this romp through the ectoplasm. An entertaining ghost story that is often more silly than spooky.

Carpenter, Stephanie | Central Michigan Univ. Press (361 pp.) | $19.95 paper Feb. 25, 2025 | 9798991064606

At a 19th-century psychiatric hospital, a patient and the superintendent travel parallel journeys toward greater peace.

“Pure food, adequate rest, wholesome influences, wholesome occupations” are the abiding principles of “moral treatment,” a novel approach to the care of the mentally ill pioneered by the real-life Thomas Story Kirkbride in the mid-19th century. At an immense hospital in northern Michigan built and run according to Kirkbride’s beliefs— which will be familiar to readers of Jayne Anne Phillips’ Night Watch (2023), set in a similar location—a 17-year-old named Amy Underwood has arrived for treatment in 1889. Diagnosed as insane by two doctors, she is in fact a lonely, alienated young woman whose encounter with a threatening group of lumberjacks left her traumatized. One of the few young people at the hospital, she struggles to establish connections and, after stealing a photograph belonging to the superintendent’s wife, finds herself demoted in the hierarchy of wards and care. Carpenter’s carefully detailed, subtly observed novel is in part a survey of the hospital. Through the eyes of the elderly superintendent, referred to only as James, the reader learns much about methods and means, staff and patients, and various aspects of illness and treatment. James is weary and overburdened. Amy is secretive and misunderstood, although friendship with another young inmate, volatile Letitia, opens her up somewhat. Intrigues involve other doctors, officials, and visitors. James’ wife also plays a crucial role,

offering firmness, compassion, and new perspectives to both central figures. She also contributes to the novel’s feminist subtext, which considers the imbalance of confident, empowered men controlling women via social as well as medical norms. There are no simple resolutions for Amy or James, yet the ground has slowly shifted for both.

Sober, sometimes dry, yet an affecting story of the potential for growth.

Celestin, Roger | Bellevue Literary Press (432 pp.) | $18.99 paper Feb. 4, 2025 | 9781954276369

A man reckons with 20thcentury tragedies. What does a life reveal when explored from different angles? This sprawling book begins in 1995 at an informal gathering of artists and academics in a Brooklyn brownstone. They’re discussing the ongoing civil war in Yugoslavia, and one of the attendees, a man from Sarajevo, says he’s going back next week. Robert Carpentier, another guest, asks why he’s returning to a place where people are being killed every day. The next step the novel takes is to jump back several decades and adopt a very different register. Here we meet a boy who’s studying for his First Communion—presumably the younger Carpentier, though the section that follows mostly avoids using names. He lives in the Tropical Republic, a country run by a politician known here as The Mortician. (Think Haiti under the rule of François Duvalier.) The political situation forces the boy’s parents to leave the country, with the rest of the family eventually following. Once they’re settled in New York City, the novel skips ahead to Carpentier in the 1970s, when he’s studying art history in Europe— mainly the paintings of Jean Siméon Chardin. After some time in Europe, he returns to the U.S., where he finds a job and embarks on a series of relationships

before marrying. Civil war in the Balkans isn’t the only crisis referenced here; Carpentier and his wife also watch as friends die from AIDS. Eventually the novel returns to the Brooklyn apartment where it began, and we see how the Sarajevo man caused tensions in Carpentier’s marriage. It’s a stylistically bold look at one man weaving in and out of history, and the subtle effects on his psyche.

An investigation of the ways history does and doesn’t shape us.

Counts, John | TriQuarterly/ Northwestern Univ. (232 pp.) | $24.00 paper | Feb. 15, 2025 | 9780810148017

A mostly marginal cast of characters struggles through life in western Michigan in these short stories. The fictional Bear County, Michigan—in a state shaped like a hand, it’s the “middle of the pinkie,” according to one character—is a post-industrial place marked by a lack of good jobs and the beautiful shoreline of Lake Michigan. Its residents long for the things their parents took for granted, like a stable family and a home, and Counts uses that generational gap in flourishing as a way to explore the American decline. The backbone of many of these tales is an encounter between one of Bear County’s young people, who are largely drugaddled and under-employed, and its left-behind elders. The conceit is interesting, but the stories are weakened because they’re populated by stock characters. There’s a sex worker with a heart of gold, a lonely boat captain, a party girl, and a hermit. They’re not fully-formed, and that makes it hard for them to have insight into themselves or their surroundings. They often just speak in blunt declarations. “It’s sad there’s no options for young people in this country anymore. The rich are filthy rich and the poor people like us are just scraping by.

Dermansky knows how awful people are inside, and can make it very funny.

It’s a shame,” one character says, before launching into a clarinet solo. A few of the stories shine, like “The Skull House,” about a reclusive old woman who builds a cabin out of preserved animal skulls. That story manages to be both deeply strange and quite sweet; there’s something admirable in Lillie Korpela, who finds that “collecting and cleaning skulls was so comforting, so soothing, it had become a necessity for living.”

A book concerning misfits should be more thrilling.

Dahl, Arne | Crooked Lane (320 pp.) $29.99 | Feb. 11, 2025 | 9798892420709

Dahl launches a new series featuring Stockholm DI Eva Nyman, of Sweden’s National Operations Department, and her Nova group, which battles impossible deadlines to identify an ecoterrorist bomber.

The first victim, the division head of a steel manufacturer, and the second, a public relations officer, are killed in mercifully limited explosions. But the apocalyptically ranting letters an unidentified source addresses to Eva personally make her fear that worse times are coming. So, she appoints her colleagues Annika Stolt, Shabir Sarwani, Anton Lindberg, and Sonja Ryd to the Nova and tasks them with rooting out the writer who’s taken defending the environment to a whole new level. Unfortunately, the hits keep on coming, claiming more and more casualties by means of a series of meticulously

planned and constructed explosive devices that aim to inflict maximum pain. Even more shocking is the news that forensic evidence points directly to former Chief Inspector Lukas Frisell, Eva’s old mentor, who’s not easy to find because he returned to university and then went off the grid years ago. At length the Nova group manages to track down Frisell, arrest him, and lock him up, all to no apparent avail. The persistence of terrorist attacks even while Frisell’s under lock and key leads Eva’s boss to make him a remarkable offer: He’ll be released with an ankle monitor if he’ll agree to help with the investigation. And he does help, right up to the moment when he escapes custody and vanishes again, leaving Eva and company to bring the terrorist to justice before he can carry out his threat to bomb Arlanda Airport.

An exhaustive and exhausting high-stakes procedural that never lets you forget how tough police work is.

Dermansky, Marcy | Knopf (208 pp.) $27.00 | March 18, 2025 | 9780593320907

A single mom and her 8-year-old daughter spend a weekend with the super-rich. When Joannie’s neighbor Johnny asks her out, and she says she doesn’t have a babysitter, he tells her to bring Lucy to watch movies with his son, Tyson, in the basement. “He promised a nice meal, and Joannie loved free dinners.

Nothing, of course, could ever happen between them because of their names. Joannie and Johnny.” Anyone who’s already read Dermansky will recognize these deadpan sentences. And, of course, something is going to happen on the very next page, actually—a billionaire couple celebrating their anniversary with a hot air balloon ride crash-lands in Johnny’s swimming pool, the wife screaming “I will kill you, if we don’t die!” Meet Jonathan and Julia Foster, a famous tech CEO and his philanthropist wife. Soon, Joannie and Julia are drinking fancy wine out of the bottle by the side of the pool and Johnny is inviting everyone for a sleepover. And the surprises just keep coming, many of them created simply by switching points of view, which Dermansky does every few pages, including not just these four but also Joannie’s daughter, Lucy, and the Fosters’ personal assistant, Vivian, an erstwhile Vietnamese orphan and 24-year-old aspiring writer. Vivian is a genius character, but honestly, they all are, and their inner monologues prove once again that Dermansky knows just how awful people really are inside, and can make it very, very funny. You might find yourself trying to put this book down so it won’t be over too soon. And when it is, you might start it all over again to see how the heck she did it. Has any writer made so much happen in just over 200 pages?

A new Dermansky novel is like a holiday declared out of the blue.

Dess, Sophie Madeline | Penguin Press (288 pp.) | $29.00 Feb. 25, 2025 | 9780593830826

In this provocative debut novel, a woman reflects on her relationship with her brother as he’s dying of brain cancer. After their mother took her own life by walking into Long Island Sound and

their father unravels from grief, Ava and Demetri, only a year apart in age, practically raise themselves. Demetri, a precocious kid, heads off to Harvard, and Ava, a talented painter, tags along, sleeping under his bed. Ava believes their identities are so entwined that she falls apart when Demetri starts dating: “It never occurred to me…that Demetri would be attracted to someone without me. Because different desires would make us what we were not—namely, two separate people.” Ava’s solution is to insert herself into all of Demetri’s relationships, convincing his love interests to slip out of their clothes and pose for nude portraits. Her greatest victory (and shame) is when she finds herself actually falling in love with one of these women. Desiring the same woman, it turns out, drives them apart. Ava is a thoroughly unsympathetic narrator, which is not itself a problem. Writers like Ottessa Moshfegh, Emma Cline, and Elizabeth Strout have created memorably difficult female protagonists. And yet, through absurdity and humor, the slow revelation of pathos, or searing social critique, their novels both wink at readers and nudge them to stop being so judgmental. It’s hard to know how we’re supposed to understand Dess’ novel, which satirizes the contemporary art world—Ava’s first major sale is a series of paintings literally produced as she’s having sex with men—and perhaps Ava, too, though her narcissism starts to feel thin and sad. Right before Demetri dies and he’s barely conscious, Ava shows him a portrait of their shared lover, seeking his approval one last time. It’s a painful scene to read. A novel that can’t decide how seriously we should take its psychologically damaged characters.

Kirkus Star

Evison, Jonathan | Dutton (368 pp.)

$28.00 | Jan. 7, 2025 | 9780593473542

Scenes from a long, unlikely, battletested marriage. Evison’s ninth novel opens in 2023, on Abe Winter’s 90th birthday party. A modest, conservative man— lifelong Republican, sold insurance for years, lives on a quiet patch of land on Bainbridge Island, Washington—he dislikes all the celebratory attention from his wi fe, Ruth, and three children. But there’s a lot going on beneath his stolid facade, which we learn more about once Ruth is diagnosed with a malignant tumor in her jaw, prompting surgery, a difficult recovery, therapy, and suddenly urgent questions regarding mortality and elder care. Evison shuttles between past and present to explore their relationship and clarify their response to the crisis. They met in college as a quintessential oppositesattract couple—Abe a prim “I Like Ike” type, Ruth a progressive poetry lover—and soon settled down and formed a family. Evison chronicles some familiar domestic-novel disruptions—infidelity, resentment over division of labor, a tragic loss—but because we know they stuck together, the novel’s mood is one of accomplishment. As Evison writes, a marriage “is shaped gradually and methodically to withstand the ruinous effects of time and outside forces beyond the control of its principal players.” Their past

Scenes from a long, battle-tested marriage begin with the husband’s 90th birthday.

THE HEART OF WINTER

challenges add to the drama of Ruth’s illness and Abe’s earnest but fumbling attempts to care for her. In the process, he affords this aging couple a dose of realism and dignity that’s often lacking in novels. Evison neatly balances their everyday lives, from running an errand to taking a shower, with a broader portrait of how couples adapt and grow closer in the face of challenges. Evison’s vision is unsentimental, but he’s rooting for Abe and Ruth, and encouraging readers to do the same. A savvy portrait of love and devotion.

Hay, Alex | Graydon House (384 pp.)

$28.99 | Jan. 21, 2025 | 9781525809859

A con woman goes up against an aristocratic family in this twisty tale of Victorian London.

Quinn Le Blanc is the current Queen of Fives, reigning over the underworld from a “humble old house in Spitalfields” known as the Château. At 26, she has her eye on a new mark and is planning the ultimate con, to be carried out in five steps over five days as all proper Château cons must. The target is the Duke of Kendal, who’s about to have a 30th-birthday ball. But the Kendal family rarely goes out in society, their money so old and entrenched they don’t need to parade it around, and Mr. Silk, Quinn’s righthand man, is wary. As Quinn sets the wheels in motion, things don’t go as smoothly as she’d hoped: The Kendals have their own secrets and a troublemaker is waiting in the shadows to wreak havoc on the whole Château. Quinn has five days to pull it off, if she can survive until then. Hay has created a specific, detailed world for his characters to inhabit, a veneer of Victorian London with the intricate rituals of the Château layered underneath. Everyone is a potential agent (or double agent), and there’s a trick up everyone’s sleeve. This leads to a

A con woman goes up against an aristocratic family in this tale of Victorian London.

twisty-turny plot, with different chapters told from the perspectives of different characters—including Quinn, Mr. Silk, the duke, and his sister— with secrets unraveling with each turn of the page. Unfortunately, however, the story jumps around so much that it’s hard for a reader to get a real insight into the characters and why they’re doing what they’re doing. The story is well constructed and the final payoff is impressive, but the book feels something like one of Quinn’s cons: full of flash and dazzle to distract from a lack of depth.

A well-manufactured but shallow tale.

Jackson-Brown, Angela | Harper Muse (368 pp.) | $18.99 paper Dec. 3, 2024 | 9781400241132

A Black woman grapples with her personal and professional choices in 1960s Alabama.

Katia Daniels hasn’t followed the typical path for a Black woman in Troy, Alabama, in 1967. At 40, she’s devoted to her job as director of the Pike County Group Home for Negro Boys, where she oversees the care of neglected and abused children with a firm hand and warm heart. She’s a caretaker at home, too—since her father’s death, she’s been the support of her nurturing mother and younger twin brothers. But the closest Katia gets to having a love life is reading romance novels in a bubble bath. She’s long been self-conscious about her weight, and a recent emergency hysterectomy has left her feeling that no man will

want her if she can’t bear children. She has a boring platonic relationship with an older man, Leon, but he’s more interested in watching TV with her mother. Then her routine gets blown up. Her brothers, Marcus and Aaron, both serving as Marines in Vietnam, are reported missing in action. At the boys’ home, Katia’s two newest charges bond with each other and with her: a sweetnatured 9-year-old called Pee Wee and Chad, who looks like a grown man but, at 14, is still a kid, and a badly damaged one. Then her high school crush, Seth Taylor, turns up on her doorstep, as handsome and charming as ever, despite having lost a leg in Vietnam—and much more interested in her than she ever dreamed possible. The novel winds its romance plot around the challenges Katia faces in helping the boys in her care and keeping them safe, as well as dealing with family issues as one brother returns deeply traumatized while the other remains missing. But as dramatic as those elements might seem, the novel rarely works up much suspense or intensity— almost every character is so well-intentioned, supportive, and loving that any moment of tension deflates as soon as it begins. The historical setting is gestured to but not evoked in detail, and the methods and atmosphere of the group home seem improbably contemporary for half a century ago.

Warmly drawn but overly idealized characters populate a predictable plot.

The bestselling crime novelist is drawn to the dark side. Given her upbringing, is that any surprise?

BY COLETTE BANCROFT

“MY IMAGINATION GOES dark real fast even if I’m doing fun things,” Alafair Burke says.

Burke’s latest thriller, The Note, grew out of one of those fun things, a girls’ weekend she spent with two friends. They were waiting for a parking spot in a busy vacation town when another car poached the space. It irked them so much that later in the evening, after seeing the woman who had done it walking by with a man, one of Burke’s friends wrote a “kind of preachy” note and wanted to leave it on her car.

Burke had another idea. “I said, as a joke, ‘If you’re going to leave a note on her car, it should say this: He’s cheating on you.’”

Their laughter drew the attention of their waitress and other diners who wanted to know the story. They didn’t leave the note—but later that evening, they saw that someone else had.

“The next day,” Burke says, “I was still thinking, What if we saw it on the news that she was missing or dead or something. I just couldn’t let it go. Three girls do something stupid when they’re really drunk and a practical joke spirals out of control.” And so, The Note was born.

“You have to remember,” Burke says, “I’m the person who took the experience of meeting my husband on Match.com and turned it into a serial killer book.” (That would be Dead Connection, published in 2007.)

The Note is Burke’s 15th solo novel. She’s written two series, one about New York police detective Ellie Hatcher and the other about Portland, Oregon, prosecutor Samantha Kincaid, as well as seven standalone novels, including The Wife, The Ex, and The Better Sister. She also co-wrote six books in the Under Suspicion

I’m the person who took the experience of meeting my husband on Match.com and turned it into a serial killer book.

series, most recently It Had To Be You, with legendary mystery writer Mary Higgins Clark, who died in 2020.

Burke, 55, is crime fiction royalty herself, the daughter of iconic author James Lee Burke. She didn’t step immediately into his footsteps, first pursuing a legal career as a prosecutor in Oregon and a professor at the Hofstra Law School, a position she still holds.

As a novelist, she established early on she was no nepo baby. Her books have garnered an array of nominations and prizes as well as spots on bestseller lists, and she was the first woman of color to be elected president of the Mystery Writers of America.

The Note won’t be the only project fans can expect from her this year. The Better Sister has been made into an Amazon Prime series starring Elizabeth Banks and Jessica Biel, likely to drop this spring.

Burke recently talked with Kirkus via Zoom; the interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The main character of The Note, May Hanover, seems like your most autobiographical character: She’s a law school professor, she lives in New York, she’s biracial. [Burke’s mother, Pearl Burke, was born in China.] What made you decide to put so much of yourself into this character?

I’m always very flattered when people say, “Ellie is so much like you,” or Samantha, or Olivia, because they’re such badasses. And I’m really not—I’m just good at faking it. I’ve got a big old impostor complex to this day.

May is like that. With her big fat brain, she has managed to get into Harvard and to law school and do all those accomplished things, but she still doesn’t really feel like she’s successful. “Fake it ’til you make it,” as she says. She’s really hard on herself. She’s always thinking, Did I say the right thing, is someone mad at me? Those parts of my personality are poured into May. May’s just not quite as good at hiding it as I am.

May has been friends with Lauren Berry and Kelsey Ellis for decades,

but in recent years they’ve been somewhat estranged. The girls’ weekend is meant to mend fences but goes disastrously wrong. What drew you to the complex nature of their friendship?

As kids you can be really close, but then as you get older you wind up in very different places. Kelsey is the rich girl, while May is still kind of struggling; she came from very little and had to work for what she has and feels like Kelsey had everything handed to her, so there’s some resentment over that. Then May becomes a prosecutor and Lauren, who’s African American, has mixed feelings about that—her life’s work is putting people of color in prison. They’re trying to put all that aside, but they wind up in the pot together when the police come knocking on the door, and those tensions start to amplify. They have to decide whether they’re going to stick with each other or throw each other under the bus.

May is also dealing with the aftermath of a viral video that upended her life. Where did that idea come from?

In 2020 I spent a lot of time online. Everybody knows the Karen memes and videos. Some of these people seem like truly terrible people. But some of them are clearly in the middle of having an anxiety attack or they’re in the middle of a mental health episode, and someone’s videoing them. They’re saying please stop videoing me, and the whole world is pointing at them and saying, “Ha ha.”

It’s the whole idea of strangers judging you at your worst moment. So I liked the idea of someone like May—who always wants to be liked, who wants to follow the rules, do the right thing—finding herself the target of that kind of ridicule. It isn’t good for her.

Another element of the book is the impact of true crime communities on the internet. Do you share that

The Note Burke, Alafair Knopf | 304 pp. | $29.00 Jan. 7, 2025 | 9780593537084

interest? And is it related to the fact that as a child you lived in Wichita, Kansas, during the days of the serial murderer known as the BTK killer?

As somebody who spends a lot of time lurking on Web Sleuth and other true crime message boards, I can say it’s an odd kind of hobby culture.

Before the internet, there was Jim and Alafair Burke in their living room playing amateur sleuths. Most parents would protect their kids from a horrible story like BTK, but my dad would be like, “Who do you think did it?” We were like amateur profilers, and we came pretty close.

I think it was the desire to solve the case that drew me to criminal law, and I always read mysteries. For someone who likes control, the reason we like crime stories is you can be scared and confused in the middle of the book, but there is an implicit promise from the writer that the chaos will end eventually, and there might not be justice at the end but there’s going to be some kind of closure, some kind of resolution. It’s fun to be able to do that as a storyteller.

Colette Bancroft recently retired after 17 years as the book critic for the Tampa Bay Times.

Penitence

Koval, Kristin | Celadon Books (320 pp.)

$28.99 | Feb. 18, 2025 | 9781250342997

A teenager’s murder of her beloved sibling opens old family wounds and brings dark truths to light.

Death and complications define Angie Sheehan’s life. At 17, she witnesses her younger sister, Diana, die in a ski accident that also injures her own boyfriend, Julian. She eventually leaves to become an artist in New York City, but just as her career begins to blossom, her father develops cancer and Angie moves back to Colorado to help run the family restaurant business and marries David, a law enforcement ranger for the National Park Service. A decade and a half later, she begins caring for her mother, who has Alzheimer’s disease, only to learn that her 14-year-old son, Nico, has juvenile Huntington’s disease. Then one night, her quiet daughter, Nora, kills Nico with her father’s gun. This tragedy sets off a series of life-altering events that include an uneasy reconnection with Julian. A successful criminal attorney now living in New York, Julian reluctantly returns to Colorado to help his lawyer mother defend Nora. Probing the memories of the main characters with sensitivity and insight, Koval takes readers on a journey into the sometimes-painful secrets they have kept from each other. Julian never tells Angie the degree of his involvement in her sister’s death or how it drove him to alcoholism, just as Angie never tells Julian—or David—that she conceived Nico just as she left Julian for David. While exploring the complexities of personal and family relationships, this engrossing, emotionally charged novel also examines the way forgiveness comes from acceptance that “each one of us is more than the worst we’ve ever done.”

An intelligent, deftly crafted suspense debut.

A playful yet earnest examination of how people interact with each other and the world.

Krow, Leyna | Penguin (304 pp.) | $18.00 paper | Jan. 28, 2025 | 9780593299654

A book about relationships and environmental uncertainty in the Pacific Northwest. Through an interconnected series of fabulist tales, Krow explores forest fires, volcanoes, time travel, and the lives of octopuses with verve and wit, while also warning of environmental perils to come. In the opener, “The Twin,” new parents Troy and Jenna discover a baby identical to their son, Jace, alongside him in his crib, sparking anxiety in Jenna. “What, exactly, was I afraid of?” she wonders. “It is difficult to fear an abstraction.” The twin, whom they name Nicholas, along with Jace and their older sister, Ruby, become recurring characters throughout these 16 stories. In “Egret,” Ruby, now grown, crashes her car into a fence, killing a neighbor’s dog. “Ruby maintained,” Krow writes, “that the accident happened not because she was drunk but because she badly needed to pee.” Even in the midst of familial or environmental tragedies, Krow’s prose maintains a playful spirit. After the dog’s death, Nicholas realizes he has the ability to create birds and wildlife; he desperately conjures animals in the aftermath of a forest fire to combat the damage. Krow’s writing is at its strongest in moments like this: descriptive, heartfelt, without polemics. When the family members all pile into a big hug, Krow describes them as being “like a geode in a rock, rings in a

tree, a nut in the shell—like everything good in nature that comes in layers.” Though Ruby and her brothers can’t always communicate with each other, they show us that while “seasons seem to be going out of fashion,” love is not. A playful yet earnest examination of how people interact with each other and the world.

Lee Chang-dong | Trans. by Heinz Insu Fenkl & Yoosup Chang | Penguin Press (368 pp.) $29.00 | Feb. 18, 2025 | 9780593657256

Short stories exploring South Korea on the verge of transformation. How does one endure life under an authoritarian government?

South Korean filmmaker Lee may be best known in the U.S. for his movies, including the critically acclaimed Burning, but this book—originally published in the 1980s and now translated into English for the first time—explores another side of his creative work. In an author’s note, Lee writes that “the short stories... in this collection are based on my actual experiences in those days, or they’re about my family, friends, or people close to me,” and there’s a lived-in realism found here—both in the fraught connections between characters and the threat of state violence. The narrator of “The Leper” learns that his father has been arrested on espionage charges, and when he confronts the older man, he discovers that his father has found an

unexpected poise and confidence. That’s not the only place where loved ones are at risk of incarceration; the threat of a family member’s arrest looms over the opening of “Burning Paper.” Sometimes, the personal and the political converge in unsettling ways. In the title story, Lee describes the way one man wound up in the army: “When the private had come home from university, wanted by the law for avoiding military service, his father had held him by his side and called the police himself. He was handcuffed in front of his father, and fifteen days later he was sent off to basic training.” The collection closes with the harrowing “A Lamp in the Sky,” in which a woman attempts to navigate the world of student activism and is eventually suspended from college. She’s offered a way back in if she informs on her peers, and is threatened with sexual violence by the authorities. These stories abound with emotional violence that sometimes boils over into the physical, and empathetically explores characters reckoning with a lack of good options. A harrowing but clear-eyed look at South Korea’s recent history.

Maldonado, Isabella | Thomas & Mercer (348 pp.) | $16.99 paper Jan. 21, 2025 | 9781662515835

Special Agent Daniela Vega of the FBI goes hunting for a most unusual treasure. Though Gustavo Toro was a highly professional hit

man, he had a conscience, and when he’s betrayed and murdered on orders from his latest employer, he turns out to have left a surprising legacy: an encrypted video meant to be watched by the FBI director in which he reveals that he’s squirreled away details on his long history of murders for hire and hopes that the authorities will find that information and put it to good use. Because he was concerned that this trove might fall into the wrong hands, though, Toro made it exceptionally difficult to find, and when Dani is given the job of uncovering it, every clue she follows seems to lead to a dead end or a dead informant because “someone is cleaning house.” Along the way, Dani’s campaign against the murky Exmyth Technologies leads to a turf war between Special Agent in Charge Steve Wu, head of the FBI’s New York office of counterterrorism, and Scott Hargrave, the Assistant Director in Charge of the FBI’s New York office, with Dani caught in the middle. At length a lead sends Dani to the Lost Dutchman’s Mine in Arizona, where she finds the crucial lead she needs. Even then, however, the author and the crime lords she’s created continue to spark so many violent new complications that Dani constantly has to call on her training as a U.S. Army Ranger. She longs to wrap up the case, which takes quite a while to wind down even after the climax, and get back to the business of helping her mother emerge from the fog that’s kept her in Bellevue Hospital’s psychiatric ward for the past 10 years. If only the FBI didn’t fly its agent everywhere by private jet, she’d be sitting atop a mountain of frequent flyer miles.

A 99-year-old Jamaican woman uses modern tools to deal with a complicated past.

PAULINE

A House for Miss Pauline McCaulay, Diana | Algonquin (320 pp.)

$29.00 | Feb. 25, 2025 | 9781643757223

In a Jamaican village, a 99-yearold woman uses modern tools to deal with a complicated past. At the center of McCaulay’s seventh book is the towering character of Miss Pauline Sinclair, who at the age of nearly 100 is driven by the sense that the stones of her house are urging her to deal with the shady history of that edifice. The stones were originally part of a backra mansion in the bush—a house that belonged to white slaveholders. Miss Pauline came upon the backra estate when she was a child fleeing sexual assault by the local pastor and eventually decided to transport its stones to build her own dwelling on a more advantageous site. Her initiative was copied by her neighbors, creating a whole village of stone houses, and when Miss Pauline became a ganja grower in the wake of Hurricane Gilbert, she was able to put in an indoor bathroom and kitchen, pay for her children’s schooling, and support the family after their father’s death. But now, as she feels death approaching, she’s troubled by the memory of a white man named Turner Buchanan who came to her in 1987 with a pile of paperwork; he subsequently disappeared and a taxi driver was jailed for his murder. She has been keeping secrets about this situation for a long time. One of the most charming elements of the novel is Miss Pauline’s friendship with Lamont, a motorcycleriding teen who helps her use Skype, Facebook, and email to reconnect with relatives and search out others connected to her story. McCaulay was inspired by the discovery of her own complex multiracial genealogy, as she discloses in an author’s note, and she’s even given some of the historic characters the names of her ancestors. As it makes its points about the complex legacy of colonialism and

recaps a century of life in rural Jamaica through the eyes of one fierce and enterprising woman, the novel educates and entertains. Alive with the sights, sounds, tastes, and smells of Jamaica.

McCluskey, Laura | Putnam (336 pp.) $30.00 | Feb. 11, 2025 | 9780593852545

A young cop and her weathered partner brave a tempestuous sea crossing to investigate a death in a remote community off the coast of Scotland. When DI Georgina Lennox and her partner, Richie Stewart, arrive on the island of Eilean Eadar, they are half-chilled to the bone and already known to—and disliked by—most of the people around them. A young man fell to his death from the lighthouse a few weeks before, and they’ve been sent from Glasgow to confirm his death was a suicide. To a community suspicious of “mainlanders,” a category that includes anyone who can’t trace their bloodline back generations, the two cops are a nuisance at best, a threat at worst, and the unfriendly welcome begins to feel downright hostile when George sees someone outside their cottage at night wearing a wooden wolf mask. She can also hear the howls of wolves, despite the fact that there are none on the island. Still recovering from a near-death experience on the job eight months prior, George is dealing with her own trauma, and her tendency to self-medicate in order to keep the headaches at bay. Five days in the salt-crusted, fish-centered village leads to little clarification about Alan Ferguson’s death, but a whole lot of new mysteries, including the disappearance of three lighthouse keepers in 1919. Even if a remote, insular Catholic island guided by a steely-eyed priest sounds like a

Joining an elite entertainment company might rocket you to stardom—or destroy you.

THE DOLLHOUSE ACADEMY

familiar folk horror set up, McCluskey is masterful at building suspense around a sense of place and a feeling of otherness. And George, fretfully uncomfortable in her skin and her partnership, is a prickly, vulnerable, completely engaging heroine with a cop’s instincts through and through, a stubborn streak that nearly gets her into trouble and the courage to risk herself in the quest for truth. Idealistic, maybe. But properly gothic as well.

Montimore, Margarita | Flatiron Books (320 pp.)

$28.99 | Feb. 11, 2025 | 9781250320650

Joining an elite entertainment company might rocket you to stardom—or it might destroy you, as two young women discover in this deliciously sensational thriller.

In 1998, Ivy Gordon is the luckiest woman in the world. Star of the hit TV show In the Dollhouse and known for her numerous award-winning albums, she’s the face of Dahlen Entertainment, a secretive powerhouse run by the mysterious Genevieve Spalding. But Ivy also knows Dahlen’s secrets, and she’s writing them down in her diary. Ivy’s story is intercut with that of narrator Ramona and her best friend, Grace, two young actresses who are invited to join Dahlen’s elite “Dollhouse Academy,” a breeding ground for up-and-coming stars. The culture reveals itself, unsurprisingly, to be cutthroat and intense in every way. Grace is handpicked early on by

Genevieve to be the next superstar, with a spinoff show and music tour of her own, but Ramona struggles in her classes and keeps getting passed over for auditions; plus, she’s kind of creeped out by the pills and medical appointments being foisted on her. Maybe whoever is leaving anonymous, threatening notes in her mailbox is actually trying to warn her away from dangers at the heart of Dahlen, like Project Understudy. No one seems to know what it is, but it’s enough to cause one student to have a breakdown, and Genevieve to threaten Ramona with instant expulsion if she ever mentions it. Maybe handsome Mason, Genevieve’s assistant, can help Ramona uncover the truth. He certainly seems to show up whenever she needs a shoulder to cry on. Montimore’s characters would be chewing on the scenery if they could; everyone is dialed up to 11, extreme versions of their character archetypes, but what could be more fun?

As if the wives of Stepford went to the Valley of the Dolls.

Murray, Victoria Christopher | Berkley (400 pp.)

$29.00 | Feb. 4, 2025 | 9780593638484

The life, work, and passion of Jessie Redmon Fauset, a lesserknown figure of the Harlem Renaissance, is examined in this historical novel.

“You’ve birthed most of us. It’s like you’re a literary midwife”: This is what her protégé Langston Hughes has to say to

Fauset toward the end of Murray’s novel. Fauset, a poet and novelist in her own right, is best remembered as the mentor of Harlem Renaissance luminaries including Hughes, Countee Cullen, and Claude McKay through her role as literary editor of the Crisis , a magazine founded by W.E.B. Du Bois and published by the NAACP. Not only did she rise to a position of prominence in the literary world—almost unheard of for a Black woman of her time—but she also went above and beyond to edit, uplift, and support her writers. One of the book’s most exciting moments comes when Jessie first interacts with the delightfully precocious 17-year-old Hughes, who has just written “The Negro Speaks of Rivers”and whose work she will continually champion and refine. But Jessie’s life is not without tribulation or scandal. Though we learn about her continual search to find a place for herself as a Black woman writer, much of the novel is taken up by her on-again, off-again affair with the married, and frequently prickly, Du Bois, whom she calls Will. (According to a historical note at the end of the book, Murray extrapolated the affair from information in David Levering Lewis’ W.E.B. Du Bois: A Biography, 1868–1963 , which called the pair “star-crossed lovers.”) At times, Jessie’s bullheadedness can be irksome, and readers may grow tired of the time Murray spends detailing her repetitive, and often saccharine, meetings with Du Bois. But Jessie Redmon Fauset is such a captivating figure that Murray’s success comes from bringing her accomplishments to greater attention. A celebration of a woman who worked behind the scenes.

Owchar, Nick | Ruby Violet Publishers (342 pp.) | Dec. 1, 2024

$17.99 paper | 9798991786300

A former priest confronts his demons in this intimate gothic tale.

Owchar’s debut novel opens in 1909 in Galicia, a rural Ukrainian province that adheres to various superstitions, one of which holds that, every night, a different person conducts a walk through the town carrying a “totem” that’s supposed to ward off any troubling spirits. On duty this night is the narrator, Yuri, who grew up in the region but then took a lengthy detour to England—where, anglicizing his name to George Frost, he entered the Catholic priesthood. Gifted at homiletics in divinity school, he won a prized assignment to a church in London, where his provocative sermons caught the attention of not just parishioners but a prominent theater critic. As word spread around his gift for oratory, he entered the inner circle of poet and artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti and poet Algernon Charles Swinburne. This experience charmed the artistic-minded George, but proved a mixed blessing: Drawn into a web of marital tension, spiritualists, and illness, he was soon psychically over his head and tempted to abandon his vows. Owchar’s setup is ambitious, and at times the prose and plotting are overly clotted, but he nicely braids the rustic, folkloric nature of the Galician community with the high-toned London Catholic one, and his depictions of poetic wits and salt-of-the-earth farmers are equally graceful. He conjures a slowly intensifying mood of despair, as George/ Yuri reveals more about the history, losses, and behavior that drew him away from London. The sermon that caught the hip London crowd suggested that the world is overrun

with demons and that God’s intervention is unlikely; Ochwar evokes the sadness, verging on panic, that such a perspective provokes. A canny and ambitious crosscontinental tale of apostolic anxiety.

Sittenfeld, Curtis | Random House (320 pp.) $28.00 | Feb. 25, 2025 | 9780593446737

The protagonists in Sittenfeld’s second collection of short stories look back—with mixed emotions. Though the characters here are largely middle-aged men and women reflecting on marriage, career, and friendship, few encounter anything as dramatic as a midlife crisis; these are tales of midlife contemplation. In “The Richest Babysitter in the World,” a professor finds joy in her own comparatively ordinary life even as she recalls turning down a job offer from a then-unknown Jeff Bezos–esque figure; in “Follow-Up,” an attorney awaiting medical test results reminisces about a hookup in law school. Sittenfeld’s characters— including Lee Fiora, the protagonist of her debut novel, Prep (2005), who reappears here in “Lost but Not Forgotten”—typically see the world with an almost hypervigilant level of scrutiny. Cutting remarks or seemingly innocuous gestures take on outsize meanings; characters analyze their own and others’ social positions through the prisms of wealth, artistic talent, physical attractiveness, and celebrity. Happily, the once-insecure Lee has mellowed considerably, and though her powers of observation, honed during four agonizing years at a New England prep school, haven’t been blunted, they’re no longer tinged by self-loathing. Sittenfeld’s politically themed novels have been wildly popular, and several stories use

politics and contemporary issues as jumping-off points for sharp insights on human nature. “A for Alone” follows an artist attempting to make sense of the “Mike Pence rule” (the former vice president’s policy of avoiding one-on-one time with women other than his wife), while “White Women LOL” features a protagonist who displays a stunning lack of self-awareness for a Sittenfeld character—a woman dubbed “Vodka Vicky” after a video of her attempting to oust a group of Black people from a bar goes viral. While the lack of resolution of several entries may frustrate some readers, Sittenfeld’s candor and matter-of-factness make for compellingly intimate and at times wildly funny reading. Astute, keen-eyed musings on lives well lived—and otherwise.

Tara, Jane | Crown (336 pp.) | $28.00 Feb. 25, 2025 | 9780593799444

You know how women start to feel invisible as they age?

Australian author Tara makes it really happen. Expect a surfeit of winsome wisdom; every chapter starts with an aphorism, and more adages are sprinkled throughout the characters’ pun-laced, cleverly entertaining conversations. After all, 52-year-old Tilda Finch is the co-owner—with her best friend,

Leith—of a company creating “inspirational posters and products.” Although Tilda’s husband left her five years ago, her life in an upscale beachside suburb of Sydney seems enviable. A gifted photographer, she’s surrounded by a close cadre of friends and is the devoted, beloved mother of successful, happy twin girls about to turn 21. Then one morning, Tilda wakes up and can’t see her pinky, then her ear. Neither is gone—they’re just not visible. Her doctor explains that Tilda has “invisibility disorder,” an incurable condition according to mainstream medical studies. The doctor recommends a support group. Tilda is disappointed that most of the group members accept that they’ll eventually be completely invisible, although some members do offer funny lines about whether Michael Jackson suffered from the disorder since he “had the signs.” Undaunted, she decides to fight her encroaching disappearance with the help of controversial neuroplasticity therapist Selma, who claims that if Tilda rewires her brain, defanging the memories of past traumas that control her thoughts, she can reverse her condition. Meanwhile, Tilda meets Patrick Carpenter, a handsome, blind musician and wealthy meditation-app entrepreneur. Tilda feels “seen” by Patrick as she never did with her ex-husband. As she evolves from cynicism concerning what she calls “woowoo” to an embrace of Patrick and Leith’s spiritual, mindful approach to life, the novel feels like her company’s extremely witty—if

You know how women start to feel invisible as they age? Australian author Tara makes it really happen.

TILDA IS VISIBLE

manipulative—marketing pitch to women who want to identify with the travails of rich, beautiful, talented, and adored Tilda. For better or worse, this is the perfect read for fans of various TV series starring Nicole Kidman.

Viel, Neena | St. Martin’s Griffin (352 pp.) $19.00 paper | Feb. 4, 2025 | 9781250906328

Anxiety metamorphoses into terror for a young Black woman fiercely protecting her own.

Like a good scary movie, this debut novel never fully explains the monsters within, but sharp portrayals, staccato wordplay, and an absolutely bloodcurdling atmosphere ameliorate the frustration of murky explanations for what follows. When we first meet 25-year-old Calla Williams, there’s not much sign from the outside that her world is falling apart, though she’s struggling at her job, trying to connect with a new boyfriend, and attempting to make a life for herself. Unfortunately, her two younger brothers, Dre and Jamie, are making it damn near impossible. With their father dead and their mother gone, the three siblings are stuck with each other, to everyone’s constant discontent. Middle sibling Dre means well, but he’s a flake who can’t be counted on to show up when it really counts. The real troublemaker is 16-year-old Jamie, full of a uniquely adolescent combination of bravado and recklessness, prone to trouble with school, drugs, and law enforcement. “It’s so hard keeping black boys alive,” Calla thinks, and her particular angst soon gets twisted into a scenario Jordan Peele might admire. When a racist cop stops Jamie at a civil rights protest, it looks like he’s about to be

another fatal victim of violent injustice, but fate—or something darker—has other plans. When a spooky little girl eviscerates the officer and shortly after a terrifying series of encounters leaves Dre marked by strange, unexplainable wounds and Calla haunted by visions of a vengeful specter, they realize taking off may be their only chance at survival. As the trio flees to a remote cabin in the woods (always a good plan in a horror story), spooked readers may find themselves checking to see what’s gaining on them.

A relentless descent into familial fears made manifest, both haunting and terribly familiar.

The Mailman

Welsh-Huggins, Andrew Mysterious Press (360 pp.) | $26.95 Jan. 28, 2025 | 9781613166109

A highly unlikely hero steps up to neutralize a dangerous band of kidnappers. Young Abby Stanfield’s horrible grades trigger an argument between her parents, Glenn and Rachel, over the exorbitant tuition at Bellbrook Academy, making for a typical Tuesday evening for the Stanfields until four masked men—Stone and Vlad and Paddy and Finn, the leader—bust into their home and hold the family hostage. Their intent is murky, but apparently focuses on a woman, Stella Wolford, and her connection to Rachel, who’s an attorney. The intruders’ plan is interrupted by deliveryman Mercury Carter, whom Finn rebuffs at the door. Carter, who’s not who he seems, calculates a bit in his Suburban before breaking into the home himself, causing Finn, Paddy, and Vlad to take off with a captive Rachel. After pummeling Stone, Carter gives chase,

A couple who abandoned their life a dozen years ago have to go on the lam once again, all because of their daughter.

NOT OUR DAUGHTER

accompanied by Glenn and Abby. The series kickoff by the prolific author of the Andy Hayes mysteries spools out like a fast-paced treasure hunt, with Finn eliciting info from the steely Rachel in teaspoons while Carter pursues him. A third narrative thread fills in the details of Carter’s rocky past in short cuts. The twisty plot relies on periodic revelations; suffice it to say that Carter is not the only character with secrets. Some additional juice is provided by the arrival of nononsense detective Rosa Jimenez, investigating a collateral victim of the villains. Welsh-Huggins keeps the story moving, but readers’ engagement will depend on the appeal of the iconoclastic Carter. A brisk and busy chase thriller.

Zunker, Chad | Thomas & Mercer (240 pp.) | $16.99 paper | Feb. 11, 2025 | 9781662516214

A couple who already abandoned their life a dozen years ago have to go on the lam once again, all because of their daughter. Long frustrated in their attempts to bear a child, Greg and Amy Olsen think their luck has changed when they foster Candace McGee’s newborn daughter. They’re right, but not in the way they expected. The night the court unexpectedly awards custody of the

baby to Candace, she turns up at their door covered in blood. Moments after warning them to flee the unknown powers who’ve targeted her and her daughter, she dies, marking Greg as such an obvious suspect that he takes off with Amy and baby Marcy. Thirteen years pass, and things seem quiet. The fugitives have made a new life in Colorado as Cole, Lisa, and Jade Shipley, until Cole’s withdrawal of a substantial sum from a Cayman Islands account to treat Jade’s scoliosis triggers a new FBI manhunt for them. Even worse, the person who killed Candace somehow turns up on their trail again. Cole, whose background in banking security and fraud makes him an ideal candidate to vanish, packs up his family in a trice and hightails it once more, followed by FBI agent Mark Burns, who happens to have a fractious 13-year-old daughter of his own, and the real killer. Zunker pulls all the stops out in keeping the chase moving like greased lightning. And if you feel that the final movement is a bit of an anticlimax, well, it’s hard to imagine how it could have maintained that tension till the last page.

Routine but highly professional thrills perfect for travel reading, preferably when you’re not being pursued by the FBI.

Samantha Harvey Wins the 2024

Booker Prize

The author took home the award for her novel Orbital.

Samantha Harvey won the 2024 Booker Prize for her novel Orbital. Harvey’s novel, published in the U.S. in 2023 by Grove, tells the story of one day in the lives of a group of astronauts aboard a space station. A reviewer for Kirkus called the book, which was a finalist for the Ursula K. Le Guin Prize and the Orwell Prize for Political Fiction, “elegiac and elliptical…a sobering read.”

Edmund de Waal, the chair of the prize’s judging panel, said, “With her language of lyricism and acuity Harvey makes our world strange and new for us.…Our unanimity about Orbital recognizes its beauty and ambition. It reflects Harvey’s

extraordinary intensity of attention to the precious and precarious world we share.”

Harvey was announced as the Booker Prize winner at a London ceremony. Upon hearing her name announced, she reacted with shock, holding her face in her hands for several seconds before taking the stage.

“I was not expecting that,” she said. “We were told that we weren’t allowed to swear in our speech, so there goes my speech. It was just one swear word 150 times.”

The Booker Prize, given annually to “the best sustained work of fiction written in English and published in the U.K. and Ireland,” was established in 1969. Previous winners include Iris Murdoch for The Sea, the Sea, Kazuo Ishiguro for The Remains of the Day, and Paul Lynch for Prophet Song. —MICHAEL SCHAUB

Samantha Harvey

The Magician of Tiger Castle, by the author of Holes, is slated for publication this summer.

Louis Sachar’s first novel for adults is coming this summer, People magazine reports.