ART IS LIFE, LIFE IS ART REMEMBRANCE DAY 2024

ART IS LIFE, LIFE IS ART REMEMBRANCE DAY 2024

Greg Melick

MAJGEN Greg Melick (Retd)

AO RFD SC

RSL Australia

National President

At 11.00 a.m. on 11 November 1918, the guns of the Western Front fell silent after more than four years of continuous war. The eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month has attained a special significance, and people in Australia and many other countries pause for a minute of silent reflection in memory of those who’ve died while in military service.

This Remembrance Day, please join us in honouring our veterans, whether it be by attending a service, wearing a red poppy, observing a minute’s silence at 11 a.m., or donating to the Poppy Appeal.

The Returned & Services League is committed to leading the nation in commemoration, and Remembrance Day services will take place at cenotaphs, memorials and RSL sub-branches across the country. As a nation, we will remember all those who have served and those who made the ultimate sacrifice in the line of duty.

For more than a century, the RSL has served its members, our nation’s current and former service personnel and their families, commemorated their service, advocated for their rights and benefits, and strongly supported the defence and national security of Australia.

As our veteran community well knows, we are living in challenging times, with our world seemingly becoming more unstable as each day passes.

The ongoing war in Ukraine; the never-ending conflict in the Middle East and the current fighting in Israel, Gaza and Lebanon, threatening to spread to Iran and wider; China’s increasing expansion in the South China Sea and ongoing uncertainties regarding Taiwan; and the tension between North and South Korea, are indicative of an increasingly unstable world.

Undoubtedly, this instability impacts Australia and the security of our nation and region. It points to the need for Australia to be vigilant and maintain a close watch and emphasis on its defence and security. These vital issues are regularly discussed by the RSL’s Defence and National Security Committee, and input from members and the wider Defence and veteran community is welcomed and encouraged via our website (rslaustralia.org/dnsc)

There is power in standing together. We stand and commemorate together. We fight for veterans’ rights together. We encourage discussions about National Security. We look out for each other, support each other and have each other’s backs.

The RSL welcomes new members and invites all current and former serving ADF to belong to the RSL.

Each edition of The Last Post is a pleasure to produce with the support, as it’s been since 2011, of Kirstie Wyatt from Wyatt Creative.

This edition, the 34th, based on art and its medicinal and empowering qualities for the individual and the communities, was a particular blessing to be part of. With help and support from a wide range of Australians, to give focus to the importance of being able to express yourself. For whilst we are one, we are also completely individual. There will never be another you. Or me.

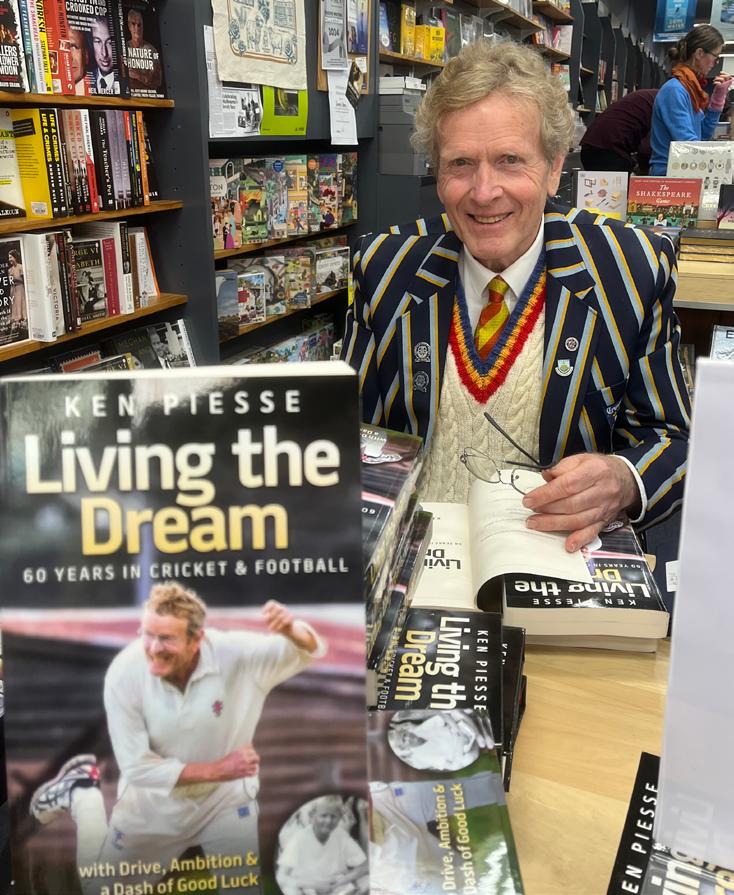

Inspirational Australian Women Lindy Lee and Kathryn Kat Rae head the interview list, with sporting guru Ken Piesse, speaking about his life and his latest book, Living the Dream. Stephen Dando Collins also, speaking about his latest book, The Buna Shots. We tribute Ray Lawler, renowned Australian playwright of Summer of the Seventeenth Doll. We take a look at sporting legend and indigenous artist, Gavin Wanganeen.

In this edition, we also travel to outback Queensland and it’s role in our military history. We also visit the beauty of outback WA as part of our expansive WA feature. We also visit the Museum and Art Gallery Northern Territory and learn more about Cyclone Tracy, on the 50th anniversary of the lethal storm.

Monique March and Moira Partridge give us unique insights into Travel.

Mat McLachlan also returns with his regular column about his Battleground Tours.

Welcome to this historic edition Art is Life, Life is Art. Remembrance Day 2024.

#thelastpostmagazine

#diaryofanindependentpublisher

2 RSL Australia Foreword

4 From The Publisher

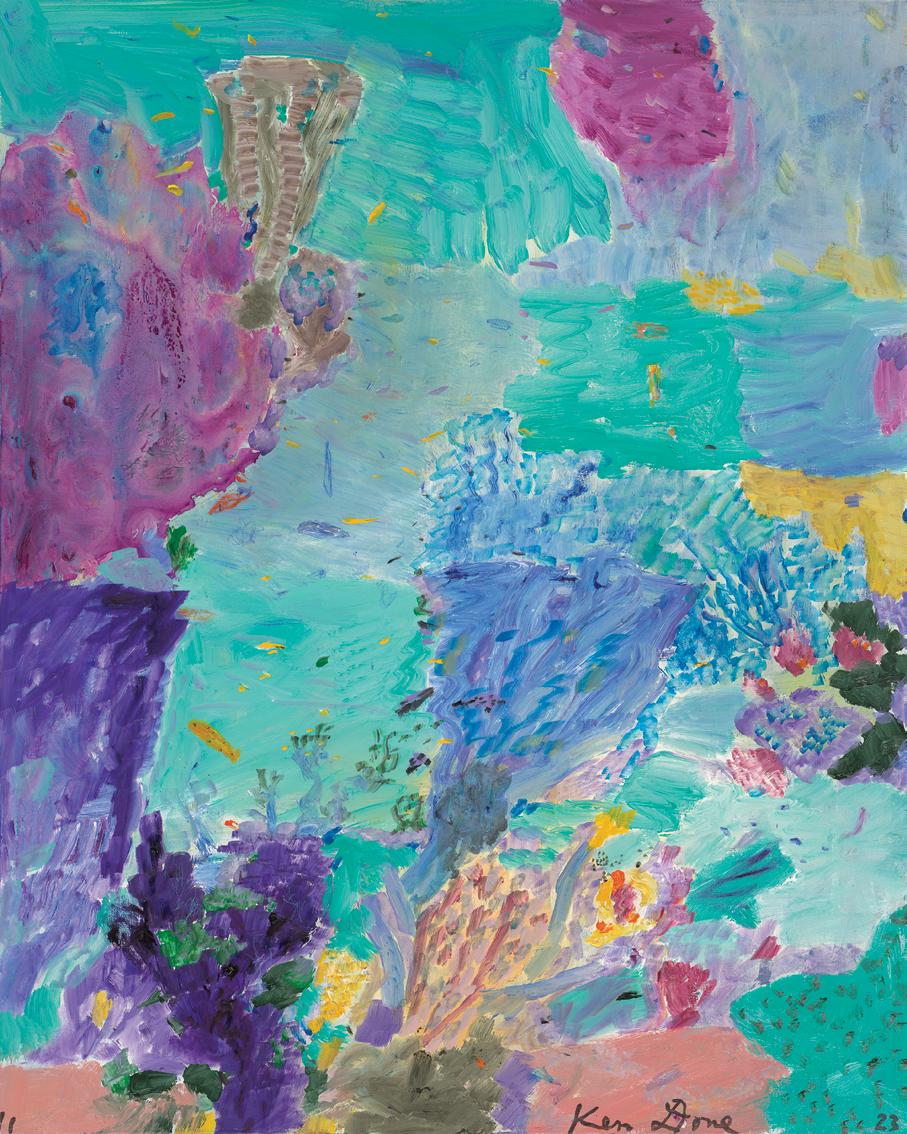

6 Ken Done

10 Peter Goers - The former ABC announcer and forever arts guru speaks about the importance of art

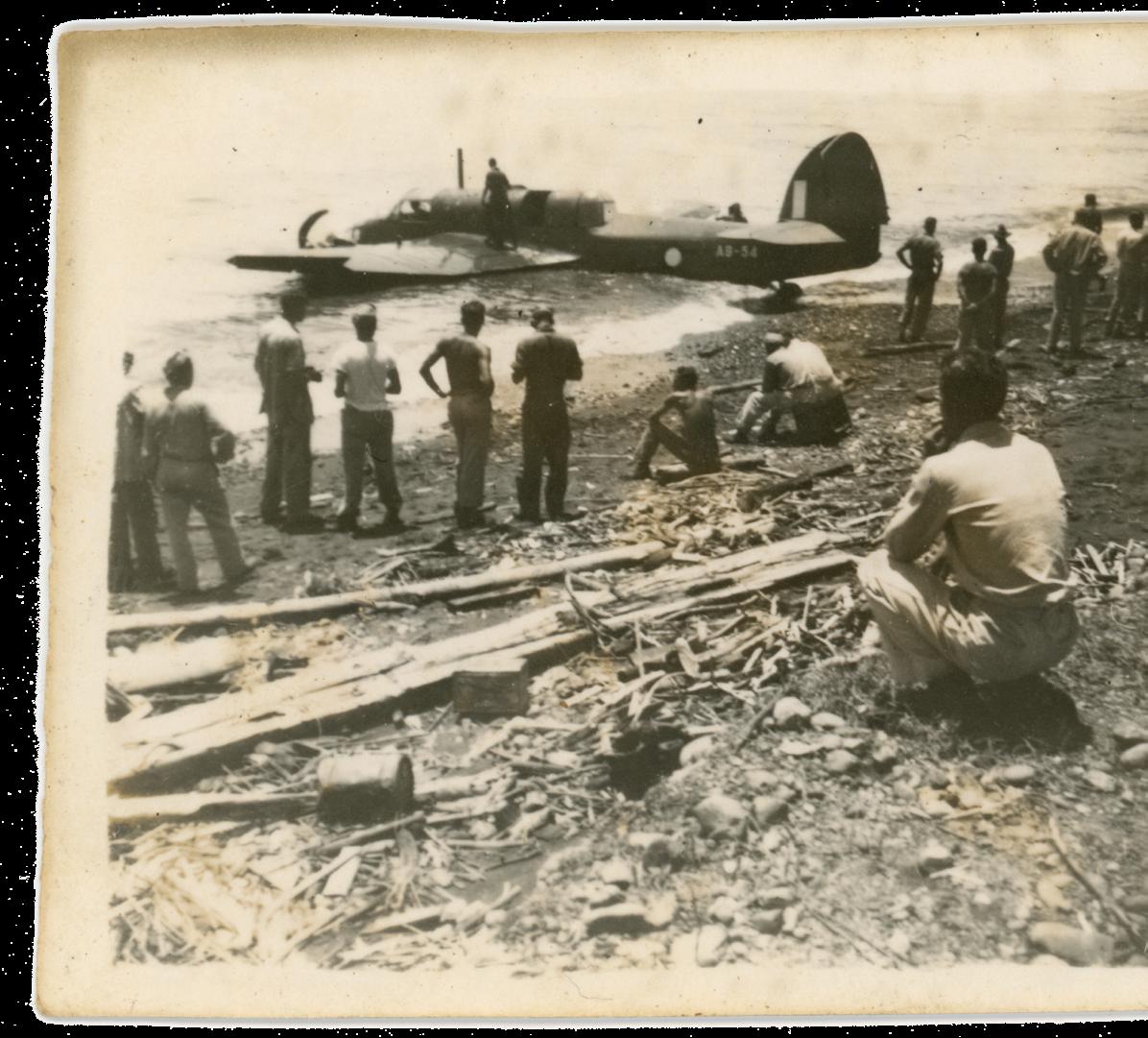

34 Stephen Dando Collins Interview – The Buna Shots

40 Vale John Bryant

42 Archibald Holman – Tobacco Tin Diary

44 Vella, Eddy, the Ross Brothers, Guts, guts, guts - Vale Adrian Burton

46 Impact 100

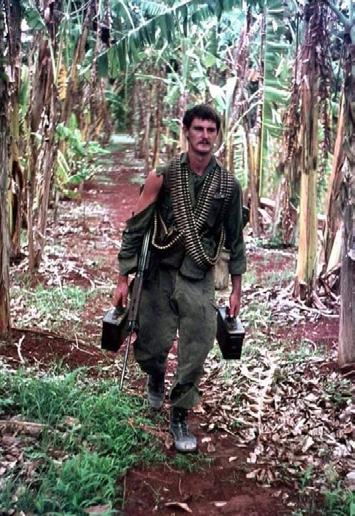

92 Warrior Soldier Brigand – Ben Wadham and James Connor TRAVEL

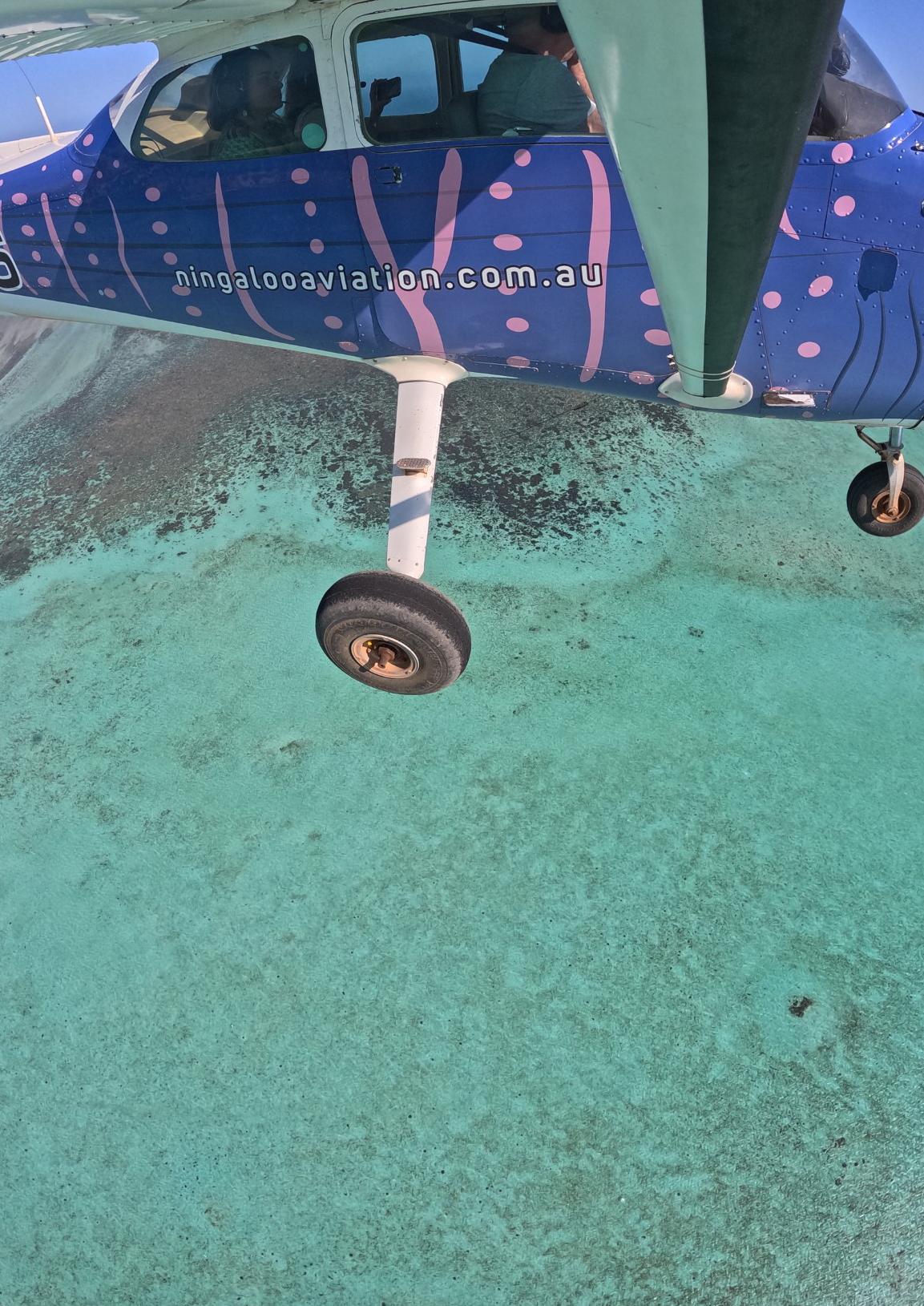

47 The Last Post Visits WA

58 Meandering Mons

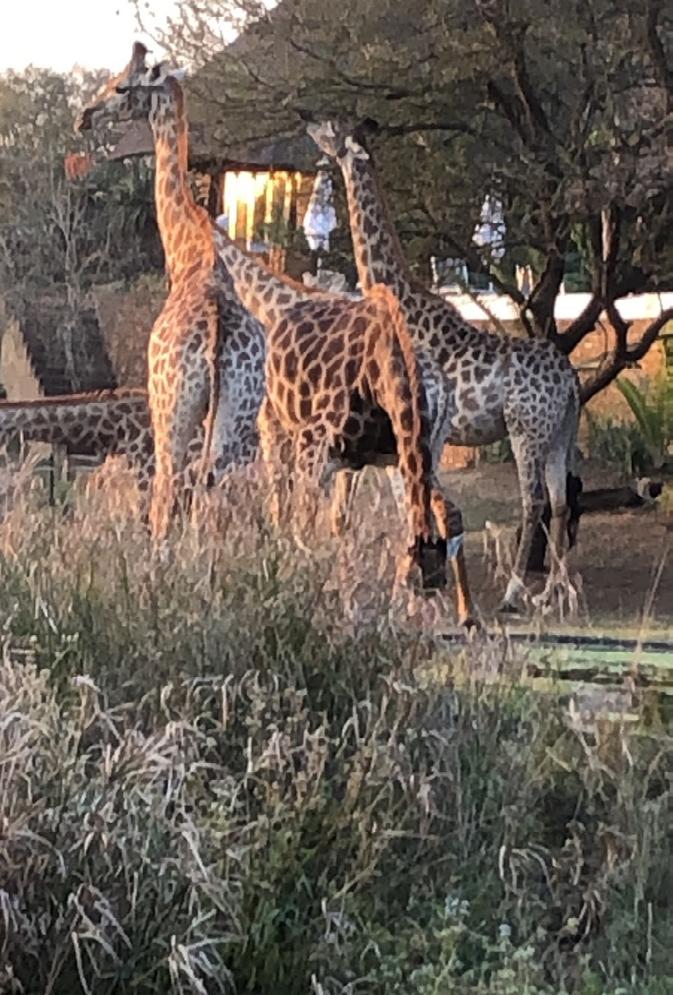

60 Rhinos on the Verandah – Stan Wilson

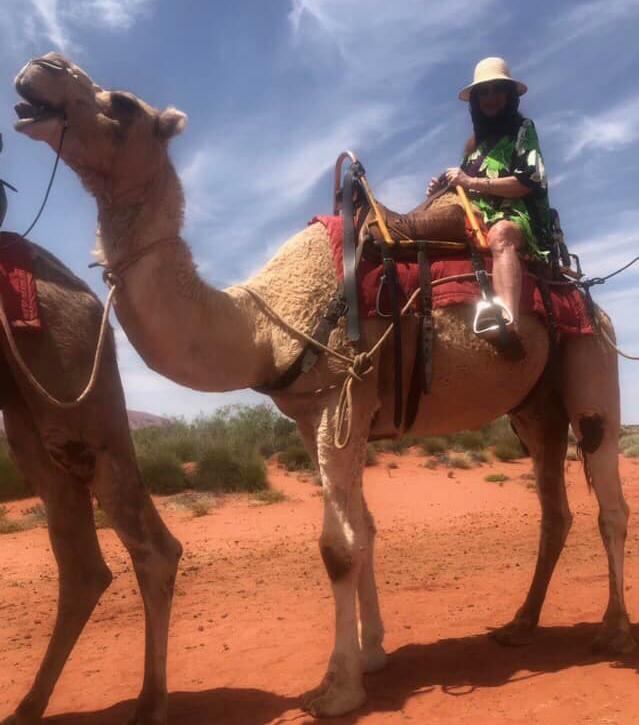

62 Moira Partridge from Uluru

66 Mat McLachlan – Battlefield Tours

68 Annabelle Brayley Interview – Morven Vietnam Nurses Memorial

72 Abigail Farrawell Interview – Charleville’s Secret WWII Base

76 Jared Archibald Interview – MAGNT Cyclone Tracy Exhibition

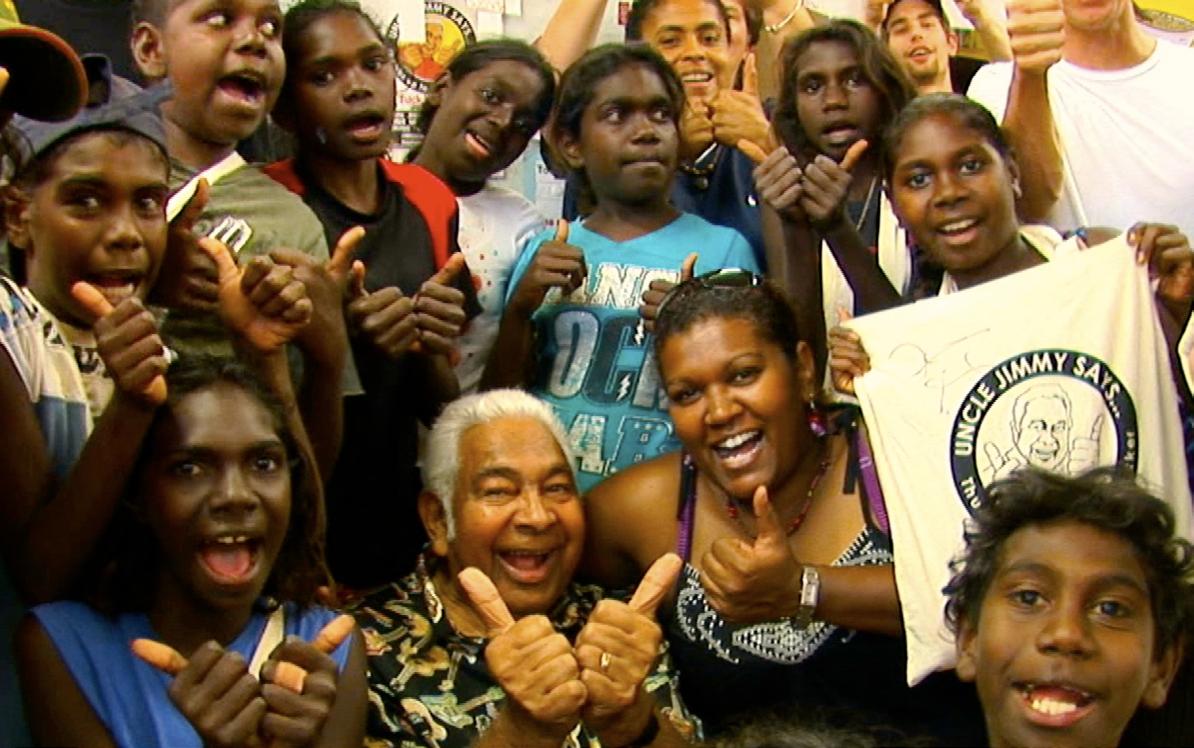

82 The Uncle Jimmy Thumbs Up Good Tucker Program

94 How wearable tech can help older indigenous people

11 Art Gallery NSW – Angus McDonald 2024 Archibald Prize

12 Vale Ray Lawler – We pay tribute to the renowned playwright, author of Summer of The Seventeenth Doll

14 Margaret Anderson Interview – Old Treasury Building

20 John Olsen – Prof Ross Fitzgerald pays tribute to his friend and famous artist

22 Gavin Wanganeen Art

24 Lindy Lee Interview

28 Aboriginal Contemporary Art

30 Kat Rae Interview – 2024 Napier Waller Art Prize Winner

96 Ken Piesse Interview – Living The Dream

101 SACA – Playing kit unveiled

102 Victoria Veterans Cricket

Last Post Magazine has been

Art is the most primitive and basic action a human being can take. The act of making a mark on something to either represent their surroundings or the people or animals that make up their life. It’s been happening since man and woman began and it will continue to the end of time, which hopefully will be a long way off.

Art is important to the individual because it’s the simplest way they can explain their role in the world or their most basic feelings. It can represent an event or an experience. It places artistic expression within the community as a whole and can be a way to make sense of the world.

For me, I like to make things that are beautiful and give the viewer pleasure over time, which is how I imagine most people want to fulfil their lives.

My father and my grandfather and my uncles were all in the war. My grandfather at Gallipoli and my Dad as a bomber pilot in the Second World War. My aunts and my Mum all worked in a munitions factory, so everybody did their bit. I can only hope that my grandchildren are spared conflict and the world can become a safer and happier place.

Art is unavoidable. It’s everywhere and everything. If you’ve ever owned or followers a Holden car you’ve appreciated the Holden lion badge and logo designed by sculptor George Rayner Hoff in 1927. It is the best known and most popular work of art in Australia.

If you listen to music, read a book, read this and any other magazines, watch TV, look at a building, tell a story, doodle, stick your kid’s kindergarten painting on the fridge, look at the design and packaging of anything, if you’ve clocked a mural, a painting, been to the theatre, to a concert of any kind, if you’ve admired a crepe paper football banner, been awed by fireworks, enjoyed fashion or been flummoxed by it, if you use furniture, if you’ve whistled, hummed, laughed at a gag or a cartoon, sung in or listened to a choir or speech, been tattooed and worn clothes you are embracing art.

Vastly more Australians attend live performance than all sporting codes put together. Only art truly unites us.

PETER GOERS

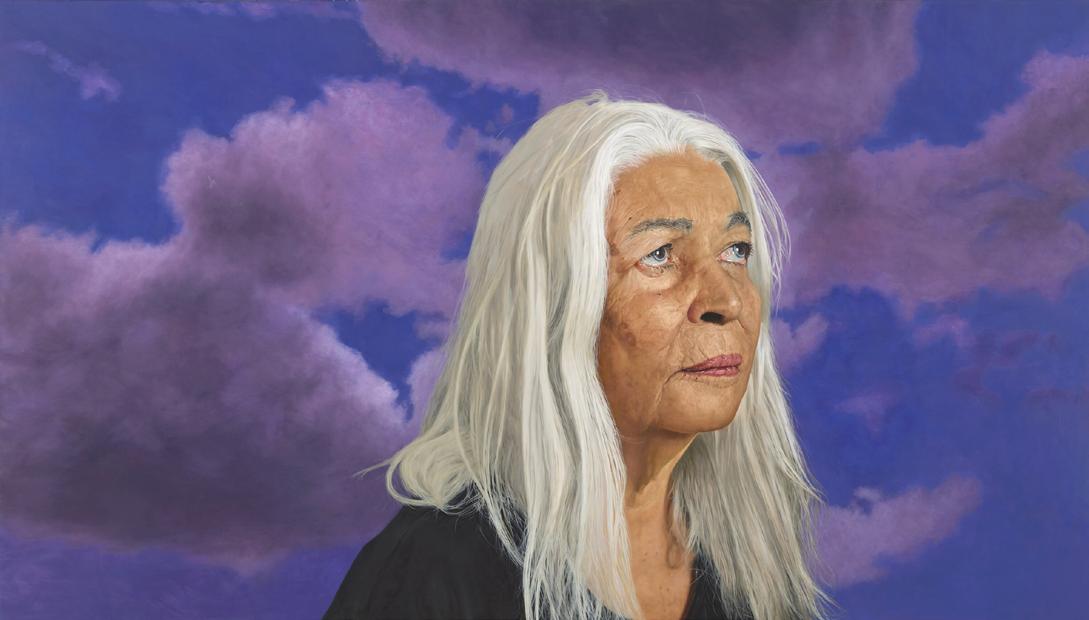

Seven-time Archibald Prize finalist Angus McDonald has won the 2024 Archibald Prize ANZ People’s Choice award for his portrait of Aboriginal writer and academic Marcia Langton AO. McDonald is only the fifth artist to have won the People’s Choice award more than once since the prize was first awarded in 1988.

Based in Lennox Head, McDonald is a strong advocate for human rights and social justice and has been working with refugees for a very long time, as shown through his painting and filmmaking practice. He flew to Melbourne to meet with Langton at her home for a live sitting where he says he was able to experience her ‘formidable intellect and wisdom’ in person.

McDonald said he was overjoyed and emotional to receive the news that he had won this year’s ANZ People’s Choice award for his portrait, Professor Marcia Langton AO.

‘I am so thrilled that the public voted my work as their favourite. It’s a privilege to be able to share Marcia’s inspirational story with a wider audience through this painting. Receiving the award is a special honour to me, but equally, it’s as much a strong vote of respect and admiration for Marcia Langton and acknowledges the profound part she has played in the struggle for Indigenous recognition and reconciliation in this country for over 50 years,’ said McDonald.

‘Marcia is charismatic, curious, direct and one of our country’s deepest thinkers. She has a well of stories which she relates with razor-sharp detail and humour, and at the same time, she radiates kindness and warmth. I wanted to portray her as both a pivotal figure in Australian history and someone who has lived an incredible life.

‘I placed her just right of centre to suggest a sense of stepping away and handing the baton to a younger group of activists after a lifetime of tireless commitment. She gazes up and to the left to reflect that she has persistently followed her own path. I’m grateful to Marcia for agreeing to sit for me, this time spent together was the highlight of the whole process.’

Born in Sydney in 1961, McDonald is an award-winning artist and documentary filmmaker. He studied at the Julian Ashton Art School in Sydney and the Florence Academy in Italy. McDonald has been selected as an Archibald finalist in 2009, 2011, 2012, 2015, 2019, 2020 and 2024. He was the winner of the 2020 Archibald Prize ANZ People’s Choice award for his portrait of Kurdish Iranian writer and filmmaker Behrouz Boochani. This work was recently gifted to the Art Gallery of New South Wales and is the first work of McDonald’s to enter the Art Gallery’s collection.

The artist is also the subject of another portrait in this year’s Archibald Prize by artist and close friend Mostafa Azimitabar. Azimitabar and Farhad Bandesh were the subjects of an award-winning documentary titled Freedom is beautiful, directed and co-produced by McDonald, that premiered at the Sydney Film Festival in 2023.

Professor Langton is a leading academic, writer and activist, and is a descendant of the Yiman and Bidjara nations of Queensland. A trailblazer in the Aboriginal rights movement in Australia, Langton has dedicated her life to the advancement of Indigenous recognition and social justice. She was a crucial figure in developing the 2023 Indigenous Voice to Parliament.

Art Gallery of New South Wales director Michael Brand said McDonald’s work was a clear favourite among visitors to the 2024 Archibald Prize.

‘The ANZ People’s Choice award is a much-loved part of the annual Archibald Prize exhibition and this year we received the third highest number of votes in the history of the award. It is always encouraging to see thousands of visitors engaging with the exhibition and voting for their favourite portrait.

‘Angus’ depiction of Marcia Langton is striking in its detail and perfectly captures her strength and determination, and the weight of responsibility she carries as an advocate for the rights of her community. We congratulate Angus on winning, for a second time, the ANZ People’s Choice award, and for his compelling portrayal of one of Australia’s most prominent Indigenous leaders.’

Ray Lawler, author of the legendary Australian drama Summer of the Seventeenth Doll, has died in Melbourne at the age of 103. His family announced that Lawler died peacefully on the evening of Wednesday 24 July after a brief illness. The playwright had lived at his home in Elwood, Victoria since 1975.

Over a long career, Lawler was an actor, director and playwright. His most famous play, Summer of the Seventeenth Doll, was first performed at Melbourne University’s Union Theatre in 1955, followed by extensive tours across Australia before transferring to London’s West End in 1957 and Broadway in 1958. It was adapted to a film in 1959. The play is credited with changing the direction of Australian drama. It has been translated and performed in many countries around the world.

Lawler wrote two more plays featuring characters from The Doll: Kid Stakes (1975) and Other Times (1976). In 1978 the three plays were published by Currency Press as The Doll Trilogy. Lawler’s other plays include Hal’s Belles (1945), Cradle of Thunder (1952), The Piccadilly Bushman (1959), The Unshaven Cheek (1963), A Breach in the Wall (1967), The Man Who Shot the Albatross (1972), and Godsend (1982).

Lawler is survived by his wife, the former Brisbane actress Jacklyn Kelleher, and their three children, with three grandchildren and two great grandchildren.

Lawler was named an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1980 and an Officer of the Australian Order (AO) in 2023. The smaller theatre space, the Lawler, in the Melbourne Theatre Company’s Southbank Theatre is named after him.

Margaret Anderson is the General Manager at Old Treasury Building, Melbourne.

Greg T Ross: Hello and welcome to Margaret Anderson, Director of the Old Treasury Building Museum in, I think it’s 20 Spring Street, isn’t it, Margaret?

Margaret Anderson: It is. 20 Spring Street, East Melbourne, if you want to be absolutely correct.

GTR: The Last Post Magazine has been in partnership with the Old Treasury Building now for a number of years. And of course, Katie and you

and the team have been wonderful for the people of Melbourne and Australia with your exhibitions. You’ve got a whole lot on there at the moment. Tell us about a couple of those. I mean, we can go through them all, but what are the outstanding ones there for you, Margaret?

MA: Oh, thanks, Greg. Well, probably the exhibition that is of most interest to some of your viewers just at the moment is a show that we’ve had on for some years, but will be finishing

quite soon. And that’s an exhibition about the various things that women did contributing to the war effort during World War II. And we called it Women Work for Victory in World War II. It was an exhibition that we did actually during COVID.

But it was a great exhibition, and the reason why we decided to do that was because when we looked through the list of what was being done elsewhere, we realized that there was very little that was reflecting

on the role that women had during the war. And of course there were some very interesting innovations that happened for women in particular in the workforce and generally during World War II. So that’s what we-

GTR: It was an interesting time, Margaret because I guess in many ways, I think this is a social observation, but in many ways, the war actually brought forward a lot of independence for women. And I guess through working during the period of the Second World War, a lot of women weren’t terribly flushed with the idea of actually giving that independence back.

MA: No, they weren’t, but they were pretty much forced to. As you probably know, John Curtin struck a deal at the beginning of the war because they worked out very early that they needed women’s labor, particularly in the factories, munitions factories and various other places which had been almost exclusively staffed by men before the war. They were also called men’s jobs. Now you probably know that at that time, the workplace was pretty much divided into women’s jobs and men’s jobs, and women’s jobs attracted around about a bit over half the wages that men were paid. So there was, at this time, no minimum wage for women. There was for men, but not for women.

So Curtin struck a deal because a move to recruit women was opposed by both the trade union movement and employers. The trade union movement was afraid of competition from women workers who were paid less. And employers were afraid that if women were actually paid more during the war, they’d go on to want more after the war and that would flow on to, so-called women’s jobs. So they were really in accord. The unions and the employers were in accord.

So Curtin, very craftily struck a deal, which was that women would be recruited and paid more. He didn’t ever commit to equal pay, and it was never really achieved during the war. There were a couple of anomalies, but generally it wasn’t. But they would be employed for the duration of the war only, and that they would give up their jobs when the men came home. And that was exactly what happened.

And so, I mean, the interesting thing was that women did get opportunities, for those who wanted them, to work in areas like munitions, aircraft manufacture, all of these sorts of jobs that everybody thought women couldn’t do, and they were paid more than they had been. The rates varied between about 70% and 90%. Interestingly, the only people who were paid equally during the war were people like medical officers.

So doctors and some very small groups actually had equal pay during the war, but they were very much an anomaly. And of course, at the end of the war, what happened? I mean, of course all of those munitions industries

and things were scaled down anyhow, but the women who had been working in men’s jobs were just quietly told, “Well, that’s it. Thank you very much.” And that included women who’d been working for the first time as clerks in the public service because before that women were not employed as clerks. They were employed as typists or as stenographers, if you remember those, or the secretaries, those wonderful, wonderful beings who did everything. They were employed in those positions, and they were positions which were capped. And so the women could never be promoted out of them, or very rarely. So the women who’d been working as bank tellers, for example, were quietly told, “Well, sorry, that’s it. You can be secretaries in the bank, but you can’t be bank tellers anymore. You need to go home and have babies.” And there was a very concerted move in the late 1940s and 1950s to encourage women to go back into the home and to make their careers as mothers and homemakers. And by and large, that’s what most of them did.

GTR: I guess the seeds were planted for what actually became a movement through the ‘60s, I guess, where it flourished. And let’s be honest about this, equal pay, et cetera is still an issue for women all these years later and it’s a bit of a sad fact. And this exhibition you have on at the Old Treasury Building in Spring Street, Melbourne, well worth a visit.

Women Work for Victory in World War II, it gives some history and understanding to what was actually happening behind the scenes away from the front line back home, and with women engaged in a whole lot of great work and understandably reluctant to give that up when the war ended.

You’ve got some great exhibitions on there too, Margaret. What about A Nation Divided: the Great War and Conscription? What’s happening there?

MA: Ah, now, that’s an exhibition that we’ve had up for a very long time, and it too, sadly, will be coming out. It’s due to be replaced with another exhibition around about January. Now, what I should say, in case anybody thinks, oh no, we’re always using that, because it’s used a lot by schools as you can imagine, both of those exhibitions are, don’t despair because absolutely everything plus more information will stay on the website.

In the last few years, we’ve developed a practice that when we open an exhibition, we put not only the exhibition itself, the content up, but we add expanded material.

Because as you can probably imagine, Greg, when we research exhibitions, we can only put a tiny fraction in. And sometimes I think we’re historians, we get a bit carried away, there’s probably too many words anyway. So we put all of that content up and that will stay.

But the Nation Divided has been an interesting one, and particularly in the context of recent attempts to amend the Constitution, because essentially the story of that is that Billy Hughes wanted to introduce conscription in World War I and would’ve been able to do it as other nations did, just by legislation. He didn’t have to amend the Constitution to do it. There was a bit of a ban in terms of sending the armed services overseas to serve. They had to be volunteers.

Now, the reason Billy Hughes went to referenda was because he knew that by that stage, he didn’t have a majority in Parliament. His own party would oppose him. He was a Labour prime minister at the start of the war and he knew that his party would oppose him.

So he knew he couldn’t get it through by legislation, and he tried to force it through driving on what he rightly judged to be enthusiasm for the war.

Now, the interesting thing about that is that the Australian people did, as we all know, support the war, both wars, amazingly generously with their lives and with their labor. But there was a sense that people who were sent to fight and to die should do so voluntarily and not be forced. And in the end, that prevailed, as you probably know. So he had another go in 1917, by which time the voluntary numbers were falling off, not surprisingly, because the scale of the losses was just so horrendous. And people were sickened by what they were reading about not only Gallipoli, but the war on the Western Front, Palestine, all of those direct losses.

And so Hughes, by this time, no longer a Labour prime minister, but leading a sort of a coalition government had another crack at the referendum and lost again.

And that’s the interesting thing, isn’t it, that thereafter, the next time that the issue of conscription came up during Vietnam, there was no attempt at a referendum. It was simply no. It was simply put through as a ballot, as we all know, with hugely controversial consequences that time around too.

GTR: When you speak about Vietnam, of course, the governments had learned of the failure of Billy Hughes to get the referendum passed and weren’t going to go down that track again. And of course, what eventuated there, as we well know, was one of the greatest, I guess, protest movements seen in Australia up until that stage to end the war, and of course, end conscription, which was a very divisive part of Australia’s history.

And of course, these exhibitions, they’re an integral part, not only of Melbourne, Victoria, but of all Australia. And when we look at, I guess, Women Working for Victory, that happened all around Australia, and of course the Great War and A Nation Divided with conscription or the discussion of conscription, again, that’s an Australia-wide thing.

1. Find a quiet spot, get comfortable and close your eyes.

2. Begin deep breathing through the diaphragm.

3. Slowly.

4. Become aware or every inhale.

5. And exhale.

6. Soon, your breathing will slow.

7. And your heart rate too.

8. During this time, the sounds of birds singing can become colours and the smell of the air, sweet and the sensation of your skin, as if being massaged with freesia petals or having spent the afternoon laying in a field.

9. Repeat points 2, 3 and 4 and 5 until you perfect the art of emptying your head.

GREG T ROSS

Fond of his own company, and not prone to idle chat, was Sidney Nolan.

A painter and poet, who wrote about women, A romantic charmer

With a rakish childhood was Sidney Nolan.

A runner for a bookie and a lark at Luna Park, was Sidney Nolan.

An exiled traveller artist who mixed myth with history And battled depression, was Sidney Nolan.

With a vagueness, yet deeper than Monet, proudly working-class, was Sidney Nolan, yet one who loved mixing with the gentry, was Sidney Nolan.

A man who worked to the music of Mozart

And a fancy for gas cylinders and polaroids and spray enamel

And with a Grandfather Who had chased the Kelly Gang, With a love for the bush, was Sidney Nolan.

A fan of painting with words and the poetry of Charles Baudelaire and his friends, And a visitor to Heide.

A fertile, angry penguin, whose brother had died when he was young.

A boy who raced bikes and suffered bruises And not prone to idle chat, was Sidney Nolan.

GREG T ROSS

My dear friend, the great Australian painter John Olsen was, at 77, the oldest artist to win the Archibald Prize.

In 2019, over a long lunch at Catalina restaurant in Rose Bay facing the Sydney Harbour, I was with John and Barry Humphries when they yarned about what might happen to John’s 2005 Archibald Prize winning Self Portrait Janusfaced.

As Barry and I were then fifty years sober, it will come as no surprise that it was John who did all the drinking!

That afternoon, in his favourite eatery, John drank moderately. The Moderation, he was delighted to tell us, is the name of a pub in Reading, at which he once drank when he was in England.

John and Barry thought that after he died, it might be a good idea that his most famous painting should somehow be made available to the nation.

It is pleasing to report that, a little over a year after John’s death at age 95, his daughter Louise, who is a renowned designer and painter, and his son Tim Olsen, who runs a leading Sydney art gallery, have gifted Self portrait Janusfaced to the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Tim & Lou’s decision was exquisitely timed.

Serendipitously, their offer occurred just after The great Archibald exhibition finished touring major art galleries throughout Australia. It had featured the cream of past Archibald winning pictures, including John’s remarkable self portrait.

John had a long history with the Archibald prize, having for many years served as a judge and a trustee.

Although he had previously won the Wynne prize for landscape twice and the Sulman prize once, the Archibald was his greatest artistic (but not personal) highlight. A deep understanding of the latter can be found in Tim Olsen’s revealing prizewinning memoir, Son of the Brush.

John Olsen’s artist statement about his self-portrait is found in one of my faultier poem, which he wrote shortly after he won the Archibald in 2005.

Janus-faced by John Olsen

“Sitting this afternoon in the studio, Summer’s gone.

Now’s the time of freckled leaves & longer shadows.

Men & women after sixty In slippered feet, Pause on the stairs, Janus faced.

Self delights in well worn brush

On an ancient palette.

Time trickles & avoids defeat. Janus faced.”

John explained that Janus, the Roman god of doorways, passages and bridges, is usually depicted with two heads facing in opposite directions. At Catalina, by then empty of other patrons, Barry Humphries quipped, “Roscoe, this was certainly true of the three of us – in our heyday.”

As John wrote wryly: “I think that this poem casts light in dark places. It informs the viewer. Janus had the ability to

BY PROFESSOR ROSS FITZGERALD AM

look backwards and forwards and when you get to my age you have a hell of a lot to think about!”

With what I think has more than an element of truth, after not winning the prize in 1989, when his self portrait Donde Voy was a clear favourite, John referred to the Archibald as ‘a chook raffle.’

But when John did win the prize, he was chuffed.

In one sense, it’s ironic that John ultimately won the Archibald. This is because, as a rebellious student at the National Art School in Sydney, in 1957 he led a group of budding artists protesting against the judges who were responsible for the conservative Sir William Dargie being awarded the Archibald for the eighth time in a row!

Thirty students stormed the Art Gallery of New South Wales holding placards and chanting Don’t Hang Dargie. Hang the Judges.

Although some protesters may not have been aware, this was an early fight for modernism – of which John soon became the leading exponent.

It is telling that Dargie won his last Archibald Prize for a traditional portrait of leading Australian industrialist and founder of BHP, Essington Lewis, who was hardly a rebel like John.

As Tim Olsen recently told me, for years his father enthusiastically sang How much is that Dargie in the Window? This aped an extremely popular song of the 1950s, How much is that Doggie in the Window?

It is so pleasing that Self portrait Janus-faced will be hung, for public view, in the permanent twentieth century collection at the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

When so many lesser lights have been gonged, it is an utter travesty that John Olsen has not been awarded our highest honour, the Companion of the Order of Australia (AC).

Surely this should happen posthumously, and soon?

Some critics say that an AC cannot be awarded posthumously. But this does not apply if someone has been nominated before they died, which is the case with John Olsen.

Ross Fitzgerald AM is Emeritus Professor of History and Politics at Griffith University. His latest books are Fifty Years Sober: An Alcoholic’s Journey and a boxed set of four Australian political/sexual satires, The Ascent of Everest, co-authored with Ian McFadyen of ‘Comedy Company’ fame.

All of these fictions feature Fitzgerald ‘s corpulent, teetotal life-long supporter of the Collingwood Magpies, Dr Professor Grafton Everest. In the latest Grafton Everest adventures ,Russia’s dictatorial president for life Vladimir Putrid and America’s President Ronald Thump are both assassinated.

Gavin Wanganeen is an Australian Football League (AFL) legend, acclaimed contemporary Aboriginal artist, a businessman and an advocate for First Nations Peoples.

TLP Takes a look at the artist behind the footballer.

www.gavinwanganeenart.com.au

Born in Mount Gambier, South Australia, Gavin is a proud descendent of the Kokatha Mula people of the Western Desert in South Australia. The Kokatha people hold the Tjukupa (lore) and have a strong connection to country, the night sky and stories in the stars – a deep source of inspiration for Gavin’s paintings.

Growing up, Gavin spent time on South Australia’s west coast where his maternal great-grandfather, Dick Davey, was a respected leader of the people of Koonibba Mission and the community at large. Davey was one of the first Indigenous people to be “permitted” to purchase land, and was a talented footballer, playing for the Koonibba Football Club, today recognised as the country’s oldest surviving Aboriginal football club.

From a young age, Gavin embraced a love of colour and storytelling through art. Yet it wasn’t until his twenties, through a friendly competition with his Indigenous Port Adelaide Football Club teammates to produce an artwork from their respective regions, that Gavin made the life changing decision to start painting.

Gavin began exploring his ancestral links on canvas, recreating memories and capturing the beauty of the Australian outback. Today Gavin’s astonishing natural talent continues to blossom, attracting national attention and acclaim and firmly establishing him as a contemporary Aboriginal artist to watch.

“MY MOTHER WAS PART OF THE STOLEN GENERATION, TAKEN FROM HER PARENTS WHEN SHE WAS A YOUNG GIRL. TO LEARN ABOUT THAT, AND COME TO TERMS WITH IT, IS A COMPLEX AND POWERFUL PROCESS.

I BEGAN PAINTING TEN YEARS AGO AS A MEANS OF BRINGING ME BACK TO MY CULTURE. ON THE CANVAS, I AM CONNECTING WITH MY HERITAGE; THE HISTORY OF MY FAMILY, MY COUNTRY AND MY PEOPLE.

I REALLY ENJOY EXPERIMENTING WITH COLOUR AND DEVELOPING MY OWN UNIQUE STYLE.”

PODCASTS: www.thelastpostmagazine.com/tlp-interviews

Greg T Ross: You’re with Greg T. Ross and The Last Post magazine. Today it’s my great pleasure to have Australian painter and sculptor Lindy Lee as our guest. Lindy, how are you?

Lindy Lee: Greg, nice to be on your podcast and in the magazine. I’m fine and exhausted is how I am, because last week was kind of intense. This whole year has been intense.

GTR: Yes, indeed. And of course, when we say intensity in this area, I guess we’re also talking about your great exhibition on at the National Gallery of Australia called Collection running until June next year, which is 2025. How’s that all panning out for you?

LL: It’s really well. It’s not actually called Collection. It’s works from the collection, and the show is called Lindy Lee for some reason. It’s all panning out. That show is in conjunction with the major work that they’ve just acquired, the Ouroboros, which is the very big sculpture now that sits very happily outside the front of the National Gallery of Australia. So she’s happy.

GTR: Yeah. Well, it’s good to have a good place and very befitting too. Lindy, born in Brisbane in 1954. You’ve come a long way since then, obviously. I guess Brisbane back in the ‘50s, maybe not the best place for an artist to be born, but as it turns out, it was. What was life like for you in Queensland or in Brisbane in the ‘50s?

LL: Well, life was ... I actually remember great blocks of happiness, but also growing up in the ‘50s, there was the White Australia policy, and so there was kind of like ... I don’t know how to explain it, but while I had my good friends and everything, but there was this overriding or feeling of just not being accepted and not being welcomed as well. You kind of also had good friends who also, because it was government policy, there was effectively that gave people permission to bully people of difference. So I think being Chinese in those days, there was a lot of racism.

GTR: Yes, indeed. Indeed. I was aware of that being roughly the same age and growing up in South Australia at the time. We did have, for a time we were in Port Pirie and my father had made friends with the Chinese fisherman. We used to go down there and he didn’t speak English, but his son did. They were beautiful people, and I was aware of this. Obviously it must’ve been a difficult time, obviously, coming from that. How did your family arrive in Australia?

LL: Well, my grandfather came probably just before Federation. Federation’s in the early 1900s. I think my grandfather came in the late 1890s and then when it was ... My grandfather spent 50 years of his life in Australia, and in fact died in Australia. But when he decided that it was time for him to return to China, the situation was that informally, you can nominate somebody to replace you. So my

father decided that he would come to replace my grandfather in Australia. So that’s how it happened. But it was also the brink of ... well, it’s also the end. This is 1946, so the end of the Second World War and Japanese occupation in China, but it’s also the beginning of the Chinese Revolution in China. So my grandfather in fact couldn’t go back because it was just ... He just couldn’t. It was just too much into that situation. But the unfortunate thing was that my dad had to leave my mother and their two sons back in China because the Australian government wouldn’t allow them to come to Australia. They were separated then for about eight years.

GTR: And they eventually made their way to Australia?

LL: Yes. Dad found a very wonderful immigration official and was able eventually to get a visa for my mum and two brothers.

GTR: Incredible. We’re so happy that that happened, obviously.

LL: I’m happy.

GTR: That’s right. As part of what evolved for you and the family later on. When did you first feel the pull towards art as a child, I guess. But if you could just explain, was there an awareness on your behalf, or did it something that creeped up on you?

LL: Well, I think there was an awareness from about three years old that I wanted to do this thing called art, but what does a three-year-old know about art? It’s just this very compelling thing. I had to draw the world. I was one of those kids who just has drawing all the time. I remember being in Kangaroo Point and we were living in a Queenslander, and the sun was streaking in and I could see all the dust motes floating in the air. As a kid, that’s really magical. Like, “How does that happen? What’s that about?” And I wanted to draw it.

I realized, in fact, that’s what I am doing now in this work, in these big works about cosmos and the universe. But the journey through that though, which is different from the awareness that you are talking about of actually wanting to become an artist, probably happened in my twenties after I struggled a lot. Because we’re talking about ‘50s, ‘60s and now ‘70s, where women didn’t have ... There were no role models for me around at that time. In fact, strangely it was my struggle with white Australia, or those feelings of not being included, those feelings of not belonging,

But it added to the fuel, because an artist needs fuel to work with. It’s not just the capacity to paint a pretty landscape or a pretty bowl of flowers sort of thing. There’s something that drives the psyche of an artist, and usually it is some deep wound or pain that you have to address. My idea about being an artist is that you’re addressing it not just for yourself, you’re also addressing it for the world, because we all feel anxiety, this

experience of alienation and of grief, and of pain and of joy, and of all those other things. What a really good artist does is try to express that for humanity so that we can actually see what’s in our souls, if that makes sense.

GTR: Very much so, and very well said. A couple of points there too, Lindy, is that true enough, I guess, with the need to express through feelings of ... I mean, if you’re living a hunkydory life and everything seems to be fantastic, it’s very unlikely that you’ll feel inspired to create.

LL: Yeah. Or to resolve questions. That’s what I think creativity is. Sometimes there’s this irritant, and you have to be creative in order to solve it. You have to search in ways that are not immediately available. I always think that creativity comes from the connection between heart, mind, and body. It’s that triad of-

GTR: Brilliant, brilliant.

LL: ... and that they all have to work with each other. Because if I was only to make work out of my head, I’d be doing the same bloody thing over and over again because my head is always only just thinking in its own way. But the creativity comes from one’s engagement with the world that comes through your body and through your heart.

So it’s all three. To make better thoughts, bigger thoughts, make creative work, you need all those three in harmony, or at least working together.

GTR: Yeah, that’s true enough. I guess, is it actually talking to ourselves when we create?

LL: Yeah, I think really, really listening to the deepest parts of us. I often describe ... I actually think that inside every human being, there’s a tribe of people all wanting different things. One’s maturity comes with being able to listen to all these voices that are inside of you and being able to work with them all. And then working with, because I’m a great collaborator as well, I like working with other people, because I’ve realized that now I’m 70 and even just before then, that it’s actually fun to play with others, and it’s fun to be able to hand over your ideas. Because I’m not an engineer, for instance, but I make massively big things, so I have to be able to collaborate with an engineer, with sheet metalworkers, with foundry.

I love that. And we all have great conversations about what we’re doing together.

GTR: That’s a good point also, Lindy. You spoke of childhood and observing things, and I guess art is an observation, and correct me if I’m wrong, but the realization that there is art in almost everything.

LL: Yeah. Art can be involved in everything, and art is about our perception of the world and how we

engage with the world. So yeah, it can be about and of anything.

GTR: Yes. We sometimes lose that ability, I think, as adults to observe with wonder at the small things that you mentioned before, which are actually big things.

LL: Yeah.

GTR: I often, not often, but sometimes will attempt to renew that glee in observing small things. I know as a child, perhaps even seeing a leaf and a flower up close was a beautiful, wonderful thing. But of course we spend time on earth and these things become commonplace. I guess your ability to bring that to light in your work and sculpture with paintings is one of the brilliant things about your work. I mean, your work encourages meditation. How is that so?

LL: Well, yeah, it encourages ... Everything that you’ve just said so beautifully is also ... The thing is that we habitually walk around in a fog of thought, our preoccupations with the shopping list I have to create, the argument that I had with my brother, the this, the that. Usually we’re always walking around in this literal fog of thought, and that fog of thinking prevents us from actually experiencing the delight of that butterfly or that flower or that sunset. We’re too busy and preoccupied to even notice these things. What meditation does, I think, is just allow us a tool to let go of that habitual thinking and encounter life intimately, firsthand, and not just through thinking, but just to receive life. Just all that thing, the stuff I was saying about heart, mind, and body. Well, meditation is actually a way of bringing all of those parts of us together.

The thing is about meditation, it has to be in this present moment. If you’re working with your body, you have to work with the present moment because yesterday’s body was already gone. Tomorrow’s body is yet to appear. I mean, your mind can travel all sorts of places, and your heart can dwell on many things, but your body can only be experienced in this present moment. In meditation and in creative thinking, I believe anyway, you can only come through the harnessing of those three parts of us, and that has to be done in the present because of the simple fact that your body can only be experienced in the present, in present moment.

GTR: Well, very meditative thoughts actually. And your painting, there is a reference to ancient Chinese practice as influenced by the Zen Buddhists.

LL: Yeah.

GTR: Is that what helps you through life generally?

LL: For sure, in terms of ... Meditation’s not about getting your life perfect, but actually noticing ... Most of us have these habitual thoughts and they’re thoughts that we’re not good enough, all of that sort of thing. Another thing

that meditation does is actually allow you to see the patterns of thinking, which are really quite destructive in your life. It’s just a bunch of propaganda that’s already been put there, that you’ve accepted as true. I hope I’m making sense, but it’s just-

GTR: I can understand completely without being, obviously, from your background and everything else. We go back to that for just a moment, Lindy, with Australia and multiculturalism. I mean, there is a tendency. There seems to be a tendency of late, and when I say of late I imagine maybe since the introduction of the internet and social media, of an ugly side of the human nature. Is this something that disappoints you?

LL: Yeah, I think because ... I’ll just put it this way. If leaders and world leaders give permission ... Being human is complex and we often want to ... When things don’t work out for us, sometimes we have a tendency to lash out. And if particular leaders in the world are allowing people to just lash out their anger rather than addressing the cause of the anger and the disappointments in their lives, I think we’re in a bad place. I just think America, if I can be just quite frank here, America is in a terrible position at the moment because it’s just ... This is the place where freedoms and democracy is a contemporary modern, the modern world, the contemporary world. But America isn’t ... I don’t know. I don’t know about you, Greg, but I’m sort of holding my breath about what happens next week.

GTR: Indeed.

LL: Because it may or may not be good. I don’t know.

GTR: Yeah, I’ve tried to say to people that may not be aware. I said, “This is a very important moment.” Very important moment. And the encouragement of gang warfare and hoodlums under the guise of free speech and political ... I mean, we all believe in free speech obviously, but there is with it both a responsibility and awareness that the world would not be as it is if not for the fact that we’re all different and we are entitled to be different.

LL: Exactly. And in fact, this is really important. The thing is that thuggish and gang behavior is not only respectful of difference. The one thing, I gave a talk ... gosh, it was last week. I gave the annual lecture at the National Gallery of Australia, and it was a big deal. Anyway, I survived, which is great. But I ended up by saying, because all of my life it’s been about this feeling of not belonging, but ultimately as I put it, everything under the open sky, everybody belongs. That is our birthright. Belonging. We can’t fall out of cosmos or the sets of relationships that brought us all together. I usually describe cosmos as the length, breadth, and depth of everything that has ever happened, is happening, and will happen into the future. None of us fall outside that set

of relationships, and so we all belong. The other thing is that belonging is not about fitting in. People who go along with thuggish or gang behavior are trying to fit in. And it’s not an original thought, by the way, but it’s just that belonging actually means being allowed to be yourself, and having courage and the grace to accept ... to grow, and thoroughly, and step up to be what you are, and having the grace to allow the other to be what they are.

GTR: Yes, that’s so true.

LL: That’s the problem.

GTR: Yeah, so true. And I guess for me at least, and I guess for you and many others hopefully. We see the example of some sections of society, and we mentioned America so let’s go back there, in proclaiming about the freedom to be themselves and yet seemingly not respecting the freedom of others to be themselves.

LL: That’s exactly right. What you said before is that freedom is very important. It’s essential to our blossoming as human beings, but that is in relation to other people and our responsibility towards other people. That’s what I mean. We’re all in this together. So if you start, once these fractures and splinters and people taking up their self-righteous causes at the expense of other people, that’s not being responsible and it’s not actually being human, I think. It’s something else.

GTR: Actually, yeah, it’s true. I sometimes wonder if we are all from the same planet originally. When observing your work, one is left with a contemplation, and I suppose that’s the desire. I’m going to just mention a couple of your works here, Lindy, and probably get a response from you if I can. In a past exhibition, A Tree More Ancient Than The Forest It Stands In, what does that mean, and what does it represent?

LL: Yeah, what a great phrase. A tree more ancient than the forest that it stands in. How can a tree be more ancient than the actual situation, its context. It was given birth to by a forest, surely. But I think it’s just that we are connected to the beginnings of cosmos. I’ll put it again. From the very beginning, there’s this river and deep connection that connects all life that has happened from the very moment of the Big Bang or however it happened. So what I’m trying to say there is that we have this access to this ancientness and it’s inside of us, and there is a kind of ancient wisdom, which isn’t about any ideology or anything like that, but just this connection to this vastness that we all belong to.

That’s what I mean. It’s a Zen phrase, by the way. So being more ancient than the tree is just acknowledging that the beginnings of us go back a very long time, and we are caused. I have this other phrase that maybe explains it as well. It’s like, the tree more ancient than the forest is also the fact that we

are historical and unhistorical. And by that, I mean it takes the whole of cosmos, the whole of history, to make this moment, where one Greg and Mindy are speaking, for instance. It’s taken everything to come together to allow this moment. So all of history. And yet, you know what, Greg, you and I have never spoken before and this will never happen again.

GTR: That’s right.

LL: This moment, That’s what I love. That is a kind of reference to the tree more ancient. We are born-

GTR: I think I understand, yeah.

LL: Yeah. We’re born at a very deep time, and yet we are also unique. Greg is never going to happen again. Neither is Lindy.

GTR: Beautiful, beautiful, beautiful. And I suppose everything we do is out there in the cosmos forever?

LL: Yeah. There’s this other thing that I love too, is that all our actions have a ripple effect into the world. We may not be able to see what it actually does, but it’s like a wind or a breeze. It’s action. You can’t see it, or you can see the evidence of it. You don’t see that-

GTR: Yes.

LL: So I just think that every life has value and meaning because everything we do has a ripple effect into the world, as the world ripples into us as well. It’s like we co-create the universe together, in a sense.

GTR: Yeah. Well said. Well said actually. It reminds me of a funny exchange I had with a friend once about this very thing, and he said that he didn’t believe in it. And I said, “Well, it doesn’t matter whether you believe in it or not, it happens.”

LL: Yeah, there you go.

GTR: What about your past exhibition No Point in Time? Is that related to that?

LL: No Point in Time, it would be. When was that? Sorry, I’ve done so many shows, I can’t even remember.

GTR: No, that’s perfectly right. I don’t know, to be honest with you, and I don’t think it matters too much, but it is something that No Point in Time, it struck me as being very akin to the truth.

LL: Yeah. Time is a really important aspect of my work, but I don’t mean clock time. I mean, there are all sorts of times, and we need clock time so that we can make ... It makes society, allows society to flow, et cetera, et cetera. But what I’m talking about is deep lived time, and that actually has no beginning and no end. And so there is time is this ... It’s not even a continuum. It’s even bigger than that. But we are just ... I love the imagery of we are creatures of time. Time is part of the fabric of our being. And in fact,

time ... and impermanence, by the way, is another name for time, really. Because everything is impermanent. Everything changes.

GTR: When you create, do you come from your Chinese background, your Australian background, or neither? What is it?

LL: It’s neither. And it’s because all of that informs the work. So it’s both me trying to understand what my ancestry can mean. It is also me being an Australian. And an Australian, I think, we can really say we are not the monoculture that I grew up in, which was basically white and nothing else particularly allowed. Now we celebrate our diversity. Some of us don’t, but the reality is that we’ve accepted it, and the spirit of Australia is the way different cultures rub up against each other and create new things. We also, by the way, I just was reflecting last week, is that we used to live with this cultural cringe. Everything Australia was derivative from other cultures. But we’ve changed that to say no. It’s not derivative. What we’re doing is actually we are mixing things in a way which is unique to Australia. We are not derivative. We are making culture from the ways in which we all interact together. I think that’s a much better ... and it’s actually a much more mature Australia that we’re coming to.

GTR: I agree. I agree. There was a song when I was growing up called Melting Pot by Blue Mink.

LL: Yeah, I remember.

GTR: I guess that, for me, was an example of why I believe that multiculturalism is a good thing, of course. Because what I basically think, as you go through life, you pick up ... “Nothing is original,” as Paul McCartney once said. So you pick up little traits and little things from the better people that you meet on the journey, and you introduce those into your own life. I guess it’s the same with culture.

LL: It’s exactly that. Nothing is original. Well, in the sense that every single human being goes through pretty much the same dilemmas that we all go through from the beginning of time. So we’ve always had to deal with this stuff, but it’s just our willingness to do it, which becomes fresh with each generation.

GTR: Yes, so true. Lindy Lee, finally, we spoke earlier about the body. You spoke mainly about the body is always in movement ... sorry, the mind’s in movement, but the body is always in the moment. How important is it for you to be in the moment mentally, et cetera, when you’re creating?

LL: Okay. So getting back to your question of whether I’m Australian or Chinese, the thing is that if you let go completely into this moment, you do it without any preoccupations about ... When I’m creating, I can’t [inaudible 00:27:30]. It’s complicated too. Of course I have a bag of tools, of course

I have my history, of course I have all of these things. But in the moment of trying to make the ‘decision’, my heart and mind have to be absolutely clear and just receive what is occurring. So it’s not about being anything, but actually cultivating the capacity to receive what is happening within the studio, with this, with that. And then build on it. Not build on my preconceptions and my ... Therefore, my preconceptions have already dictated what it’s going to be, because I’ve already had that idea. That’s what a preconception is. To be truly creative, actually, is to acknowledge that you’ve got all this stuff, but to arrive at a point where you genuinely ... It’s a Zen thing. In Zen, there’s a beautiful expression, “Only don’t know.” Meaning, don’t put your preconceptions, all of the constructions that you’ve ever thought about the world, leave them aside and allow the world on what’s happening within this space, in this minute, to speak with you, and see what happens. And that’s the discipline.

GTR: That’s wonderful. I guess also, Lindy, it’s about finding that balance, that delicate balance of trust and whatever, I don’t know if we call it naivety, but trust, to remain open through your life. Because, of course, you can only accept things by being open.

LL: That’s right. In Buddhism, one of the great [inaudible 00:29:15]. Okay. One of my favorite vows in Zen Buddhism is, “Dharma gates are countless. I vow to open to them.” That just simply means ... A Dharma gate is just like in every single moment of your existence, you have a choice to be open or shut down to your life. I vow to be open to them, is that I vow to be open to every single moment of my existence. I love this bit. Even if you’re shutting down, even if it’s just too hard to bear, then you are okay. It’s like, “Okay, I can’t deal with this at the moment.” Or, “This is too painful.” But even acknowledging that is being open because you’re being true in this moment to exactly who and what you are. That is the way I try to live my life, and of course I fail all the time, and that’s okay.

GTR: But we do gain from that openness too. Thanks for your honesty. I guess there’s so much more to talk about. It’s an incredible thing. I’m stimulated by your work to the point where it encourages discussions on philosophy, so thank you very much, Lindy, for being part of this.

LL: A great pleasure, Greg. I just wish you luck with all these podcasts and stories.

GTR: Thank you so much. It’s a wonderful thing. We’ve been speaking with Lindy Lee, famous Australian painter and sculptor, whose exhibition is a collection of Lindy’s work. Lindy Lee at the National Gallery of Australia until June next year, 2025. Get along and see that. Thank you once again, Lindy.

LL: Pleasure, Greg.

Aboriginal Contemporary is a Sydney art gallery committed to the fair and ethical treatment of First Nations’ artists and their communities.

Owner, Nichola Dare, regularly travels to remote art centres in Australia’s central and western deserts, and Arnhem Land. Together with her understanding of indigenous culture and Country and exquisite eye for fine art, the trusted relationships she has built over 14 years enables her to source artworks not otherwise available to Australian buyers and collectors.

Aboriginal Contemporary has a year-long exhibition schedule, showcasing both established and emerging artists. Paintings by senior artists, whose work hangs in international galleries, can cost up to $20,000, but there are also smaller artworks that mean anyone can have authentic Aboriginal art in their home for just a few hundred.

Australia’s First Nations peoples are the world’s oldest continuously living culture and ethical practices and the fair treatment of artists are a cornerstone of the gallery’s business model. Aboriginal Contemporary is longstanding member of the Australian Government’s Indigenous Art Code.

Greg T. Ross: Welcome to The Last Post magazine and Radio Show, Kat.

Kat Rae: Hi, Greg. Thanks for having me.

GTR: It’s a pleasure. And geez, when I look at your work, and I feel inspired because of course we do have an edition coming out with the Art is Life theme and you’re a good part of that. You’re the winner of the 2024 Napier Waller Art Prize.

Now of course we’ll go into the meaning of all that, but I guess from your side, what did that mean for you?

KR: It meant enormous, a lot. It was very validating, first of all, as an emerging artist and someone who left the army after 20 years of service, to become an artist. To be validated by institutions and a judging panel of such high caliber was very reassuring that I’d made the right steps.

In addition to that, the work itself was enormously poignant with very important messages of which I wanted to have broadcast at a national level.

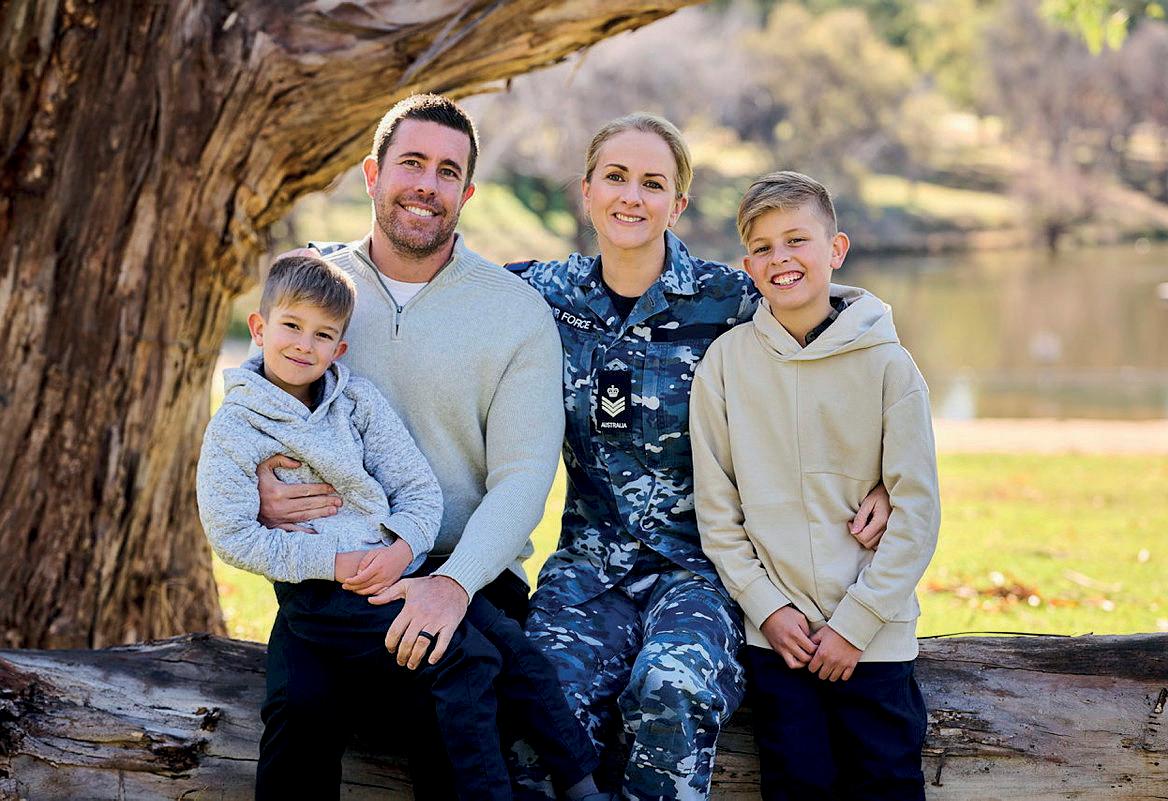

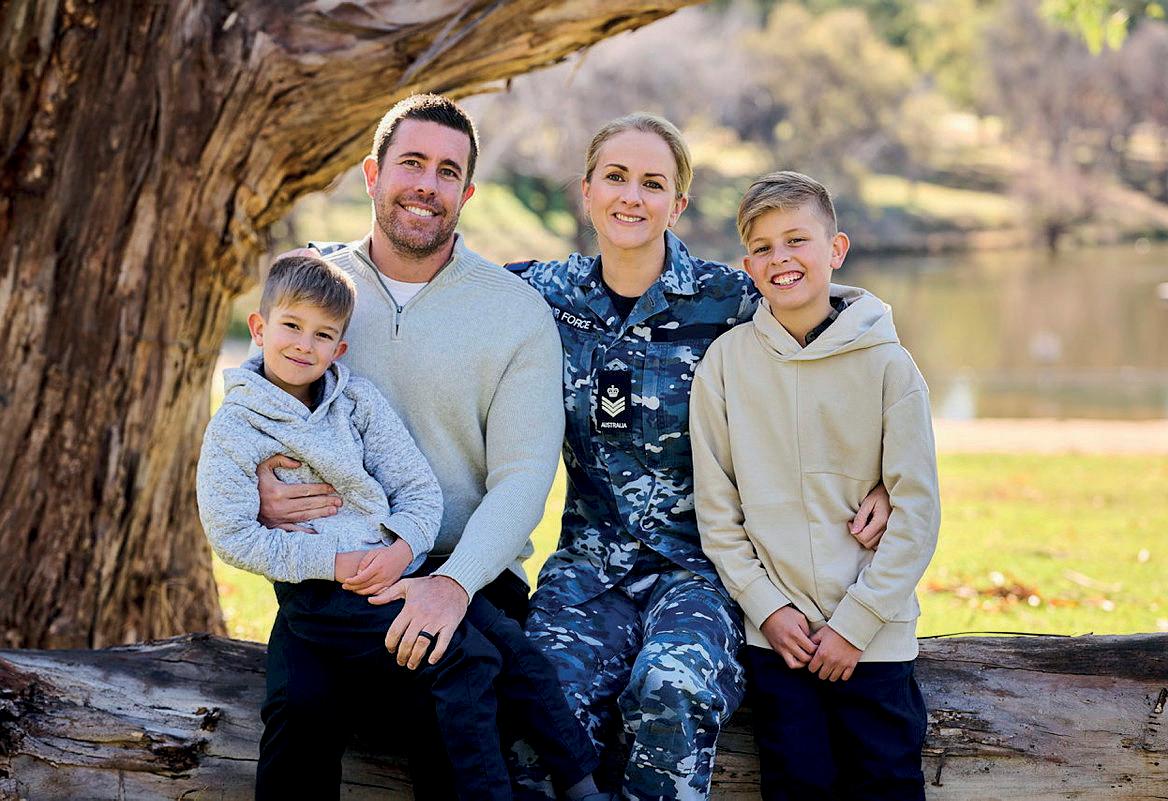

The Australian War Memorial is proud to announce that Kat Rae, who served in the Australian Army for 20 years before becoming a full-time artist in 2019, has won the 2024 Napier Waller Art Prize with a thought-provoking installation.

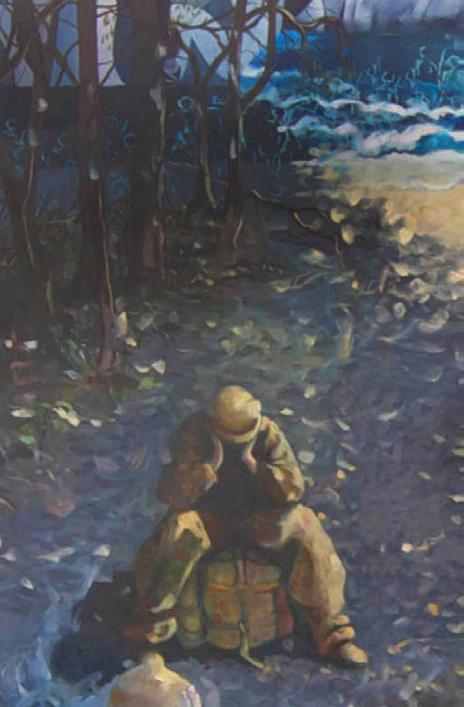

Her winning artwork, Deathmin, is comprised of stacked paper, vinyl, plastic, leather and metal representing the "stack of post-death admin" the artist inherited after her veteran husband Andrew suicided in 2017. Ms Rae took inspiration from her late husband’s experience with the Department of Veterans’ Affairs and her own experiences with the Inspector General ADF and the Royal Commission into Veteran Suicide when creating the work.

2024 Napier Waller art prize launch event, 29 May 2024. AWM24.PR.058.

And to be able to contribute to a dialogue in Parliament House with War Memorial hierarchy, military hierarchy, and politicians, as well as the general public, felt really important to me.

GTR: Of course, the winning piece was your Deathmin. Now, I guess art cuts through on so many levels, and of course there’s so many levels to the story of the creation of Deathmin. Can you just describe for listeners what it’s actually about, what it looks like and the art of creating this?

KR: Well, first of all, I should probably give a little trigger warning up front that the work contains themes of suicide, domestic violence, and I guess weaponization of bureaucratic administration, of which I know a lot of veterans would feel pretty triggered about.

So yeah, the artwork itself is a stack of paperwork. At my height, I’m 5’3” and the weight of my late husband, so well over 100 kilos of paper. And

it’s the actual paperwork of which he petitioned to Department of Veterans Affairs for support for his broken back and his declining health. Then after he suicided, it’s the paper trail of after his death, which involved me with legacy, freedom of information, all of Andrew’s paperwork, and then trying to build a case which took over a year to claim more widow status.

It has coroner’s reports, it talks about police reports from the domestic violence that I experienced at the hands of Andrew before he died. It has the Inspector General ADF drafts and redrafts whilst they tried to look the other way and blamed his death on anything other than Defense. So yeah, it’s a massive stack of paperwork and I think anyone who’s a veteran would understand how difficult it is to keep applying thousands and thousands of pages to get the support you need.

It also talks about the cathceresque nature of institutions and how they ask

for your whole... well, they ask you to put your life on the line, but then when you need it, they don’t support you back.

GTR: Look, what an amazingly unique way of expressing your reaction to a situation that many hope not to go through. The essence of art, I guess, is to make us think, and everyone will have a different definition of their... Well, everyone’s reaction will be slightly different, but I think on this level, it’s such a unique expression. It comes through loud and clear. That’s one of the reasons that no doubt that you won.

I guess the Head of Art, Laura Webster, is it at AWM, was appreciative of your work. Look, Andrew’s suicide in 2017, Kat, life obviously changed from that moment on, but had it been changing before that? Had this been an evolution and an evolving of a situation that you saw coming or did it take you completely by surprise?

KR: Well, look, he had been injured on Special Forces selection course back in 2010, and then again in 2011. So he had life-changing injuries with a broken back after that, and he was in chronic pain. So look, that was pretty life altering and mood altering. And I guess he was on a decline after that, even though, I mean, he deployed after that, he still got promoted after that, and he did his best to rehabilitate himself.

I mean, I guess I could see that he needed support and he was trying to get it through DPA. I was trying to provide it the best I could as well. But yeah, I guess I kind of was surprised when he died. It’s in some ways shocked but not shocked. Shocked and horrified, but also in some ways, I’m not surprised. I’d always thought that I would be a young widow in the fact that he lived his life with so much risk taking. But I kind of expected by young widow, I thought maybe fifties or sixties, not in my thirties.

GTR: No, it certainly is a life-changing situation to lose a partner no matter what the circumstance and of course, things had probably got a little out of hand there. Anyhow, as far as your expression with art, were you driven during your years in the Army to express yourself with art or was this something that had evolved from childhood? When did it actually start happening for you with art?

KR: Yeah, I always would wanted to be an artist as a child. And I remember my mum asking me what I wanted to do when I grew up. I was in year 10 and I said, “I wanted to be an artist.” And pretty much without missing a beat, she said, “Why don’t you join the Army?” And I thought I’ll just appease her by applying, just because I also did Army Cadets and I grew up on a farm and I was the oldest of six children. So I already had

a fairly robust life experience, and I guess had leadership through just even being the oldest of siblings.

So yeah, I did get a scholarship to go to Australian Defense Force Academy. And at that time I thought, well, yeah, I guess a lot of my favorite Australian artists had done military time. I’m thinking about Arthur Boyd and Albert Tucker and McCubbin, like a lot of these guys had done their military time. And I thought, well, I guess part of being an artist is garnering an interesting life. I mean, I probably got a little bit too much bargain for.

But I remember early on at ADFA, we went to the Australian War Memorial. It was the first time I’d ever been there in Canberra, and I saw how much art was in the War memorial, that took me by surprise. And I thought, well, maybe I can be an artist because there’s war artists. I didn’t realize.

So then I realized that actually war artists are people who are commissioned by the Australian government to fly in, fly out and depict the war as an outsider. So I guess along my artist’s journey, I’ve realized that actually the experience of veterans and war widows, there’s a whole lineage of them from trench art who were actually making art that was from their lived experience. That was not to diminish anything of official war artist because of course those experiences are real as well. But I think being a veteran, it gives you a certain privileged experience of service, especially over the course of 20 years.

In addition to being a war widow, I felt like, well, actually I can contribute back to the National Archives here and make art that talks about lived experience. Yeah, I kind of consider myself an unofficial war artist now.

GTR: Yeah, yeah. Well said. I mean, a lot of people at the beginning before delving too deep into this, wouldn’t maybe not see the connection between art and war, but there is a big connection, and as you’ve just noted, some of the artists that have been part of a military service. So it’s becomes part of Australian history also. During your 20 years in the Army, Kat, tell us what you did actually just give us an outline of what your day-to-day routine was.

KR: Well, I guess in the Army it’s a whirlwind of experiences and postings and deployments and courses and moves throughout Australia. So yeah, I guess I went to ADFA as an army cadet and did an undergraduate humanities degree in, well, I did a double major in literature and I did politics and history.

I went to Duntroon and after that I graduated as a lieutenant and I posted to Hobart as the Adjutant, a

reserve unit down there. And then after that I posted to Darwin as a platoon commander. As an ops’ lieutenant actually, and then as a platoon commander to Kuwait. After that, I posted everywhere in between, from Darwin to Melbourne and Sydney, Canberra and doing a range of jobs from 4th-line logistics to... Sorry, I’ve got COVID, so I’ve got a bit of a cough.

GTR: Yeah, that’s fine.

KR: And then training institutions, representational work, ceremonial work. I deployed three times all up. Once as a lieutenant, once as a captain and once as a major. I was at Command and Staff College doing a master’s in military history and defense strategy, when Andrew died. After that, I was posted to the career agency for officers, as a career advisor.

Operated after that as a lieutenant colonel and did a posting at joint logistics command as the ops officer. At that point, I realized how difficult it was to be a solo parent of a very young child. Andrew and my daughter was at that stage about three or four. She was two when he died. And I also just felt completely burnt out by the experiences of it all.

GTR: Yes, it was 2019, wasn’t it, when you decided to leave the Army and become a full-time artist?

KR: Yeah. And then I just realized that I’d always really wanted to be an artist. And from my experience with Andrew, I realized you’re not guaranteed a long life. I was in my late thirties by that stage, and I felt like if I’m going to give this a go, I really need to move or else I won’t give it enough time in my life to really explore and give it a proper go.

So I decided to leave the Army and apply for art schools. And I got into RMIT, School of Art in Melbourne, and I’m just finishing my honors there now.

GTR: Well, congratulations on that too, Kat. And I guess with art, is it imagination that fuels creative skill or creative skill that fuels imagination? It’s such a wonderful beast. It would be hard to describe, but you would have thoughts going through your head daily about new artworks and creativity.

KR: Yeah, I do actually. I feel like I’ve got a lifetime of experiences of which I can make art about. I’m also really engaged thanks to the education that the military gave me into the political and cultural landscape of this nation. So I’m always interested in making art that’s relevant and tries to contribute to a national dialogue about the things that I really care about.

I guess most artists would appreciate just actually how difficult it is to be an artist because it takes so much time to be good at anything. And there’s so many mistakes, and in some ways

it’s not like the army, which is quite validating. It feels like every year going on another career course or another posting or promotion. When you’re an artist, there’s not so many validating elements because no one’s going to stick a badge on your chest or another pip on your shoulder. You’re just working alone a lot of the time, thinking deeply about things and making lots and lots of mistakes. So yeah, I hadn’t really experienced... I had thought about how difficult it would be, but at the same time, I think it has been really important to find studio spaces or new community and the sense of discipline of which you have in the army, but you can transfer into artist life and try and be... and mix with artists who also really understand the challenges involved with it all.

A bad day at art school was nothing like a bad day in the army and the fact that no one’s probably going to get killed or anything like that. But at the same time, there’s challenges to make it real and poignant and of making art of gravity. I mean, I live in Melbourne where there’s an artist in every corner. There’s job shortages all in Australia for skill shortages, but there’s no vacancies for artists. It’s probably there’s thousands more artists than there are jobs for it. So yeah, it’s got its challenges, that’s for sure.

GTR: Well, it’s interesting you say that too, Kat, because there is art in everyday life, and I guess it’s the artist’s blessing to be able to see that. And maybe some people need a reminder of this through the work of artists like yourself and writers and musicians, et cetera, that there is art in everyday life. You capture that well, I guess with your work Deathmin and the story behind that, you’ve captured that so well.I guess also, Kat, to be an artist, an underplaying of this is that you must have true belief in yourself and your ability to express yourself?

KR: Yeah, I mean, I feel like sometimes the greater the doubt, the better the faith. You know what I mean? That idea that, I think as an artist, you’re regularly questioning yourself. I mean, every now and again, I make something and go, “Bloody hell, genius.” But mostly I’m like, “Is this silly? Is this a real job?” So there’s definitely...

But I know there is art in everyday life, and I think there’s a certain... I think a lot of people... What I really like about the Napier Waller Art Prize that the War Memorial runs, but also the work that Australian National Veterans Art Museum ANVAM does is they show veterans and veterans families and the wider community I guess the cut through, the important cut through that art does give to people. The way that it does transcend language and life experience and words and connects people on a transcendational kind of way.

I mean, it’s really beautiful to see a connection of such disparate veterans, which can often be quite tribalistic and fractious in some ways, services,

years of service, officer, soldier there’s so many friction points in the veteran community, but art can surmount those things.

GTR: Yes, it does have a way of cutting through. And I guess that may be exemplified by dementia patients who may forget just about everything, but remember the words to songs, et cetera. So that’s a beautiful thing too. Now, writers have writer’s block. Do you ever have a painter’s block or an art block where you find it hard to...

KR: Yeah, I guess so. I often go to an exhibition if that’s the case and see what other artists are doing. I often journal or do some exercise, go for a walk, listen to a podcast, I go to an art opening and talk to different artists about what they’re doing. I read broadly.

I think sometimes when you just show up and try, that’s when the magic happens. And I guess for me, I’ve got a lifetime of experiences of which I can draw on. I don’t normally feel blocked in that respect. I guess for me also, I’m a solo parent to a now 9-year-old so my time is extremely limited. I’m so busy with raising her and trying to forge a new career that I’m on the clock as soon as I’ve dropped her off at school and I’ve got six hours to produce and make and think and also keep fit and run the household. Yeah, I kind of feel like sometimes having those severe time limits actually ensures that I don’t have time to sit blankly-

GTR: Yes, yes, I understand completely.

KR: ... at the paper. I don’t know what to do.

GTR: Yeah, no, I understand completely. It reminds me of, as we get closer to the closing dates of each edition of the magazine, somehow I seem to be doing more work and doing more good work, and that’s interesting.

So with life, I guess memory, all these contributions to art, experience, everyone’s going to have a different way of expressing themselves. And we’re so glad that you’ve left the Army and become a full-time artist because it’s a wonderful contribution to the history of Australia and to the history of art in this country. And I guess almost finally, Kat, how important is art? How important is it?

KR: Well, I think it’s essential to humanity. Artists hold up a mirror to humanity and ask for a better version of ourselves. You and I were talking about out how difficult it has been during the invasion on Gaza and the complete crimes against humanity that are happening there, and how important it is for artists if no one else would stand up and speak out. How important it is that artists ask for a better world and can try and traverse the barriers of language and beliefs and try and really agitate change.I mean, I’m not idealistic enough to

think that art will change everything, but I think I could definitely try and make a difference.

GTR: Actually, that’s very good point. Because if art is silenced, it will never be, but if it is attempted to be silenced, then we increase the risk of moving to a world examples given with 1984 and Brave New World as two books that come to mind. And I guess when we were younger, when I was younger, I did believe for a number of years that we could change the world. I know now, and I’ve known for a long time that that’s not going to happen. But in a small way still, perhaps.

KR: Yeah. I mean, and even if what we’re doing to humanity in our environment is on an irreversible descent downward, at least we’ve still got art, thank goodness at least.

GTR: And holds up a mirror that’s what allows us-

KR: Even as the Titanic was sinking, the band kept playing. So yes, thank goodness for art in real-

GTR: And it does hold up a mirror to ourselves. And I guess that’s one of the reasons why everyone will see art from a different perspective because it’s holding up a mirror to each of us, and each of us is different. So yeah, I understand completely on that. What are you doing now? Any great works?

KR: What am I doing now. Yeah, so I’m finishing writing my Honors Exegesis, which is like a small thesis, and I’m entering my work into art competitions. I’ve just finished a group exhibition with some friends, I did Honors with. Full circle, I guess, when I was at the Australian Defence Force Academy. And one of my teachers taught me war literature, Adrian Caesar. He’s now a published author, novelist, and poet. He’s writing a poetry book, which he’s asked me to illustrate. So it’s great to reconnect with someone who, I was an admiring student of him as a teacher back in 2000. Now, quarter of a century later, we’re collaborating together, which is really great.

GTR: That’s fantastic stuff. And poetry is a great way to express yourself too. And of course it’s greatly edited, which suits some of us because there’s not too much carry on. It’s always very much to the point, poetry, which is beautifully... Rather like painting, I suppose, because once you’ve done a painting, you can’t edit or expand on that. There it is. There it is.

Kat Rae, it’s been an absolute pleasure speaking with you. We could go on for hours. I know there are so many issues associated with art and the role of art in a society of turmoil and war that perhaps it invites another podcast of itself. But in the meantime, we do thank you very much, and may good things continue to happen to you in your role as an artist.

KR: Thank you, Greg. It’s been wonderful to talk to you.

Philadelphia cheese on bagel, toddler vomit on marble floor, three palms thru the window like hairy insects on poles.

A winter breakfast at the Portofino Inn café.

Outside, L.A. dude feverishly smoking in car, listening to ‘Barrel of a Gun’ by Depeche Mode; blond woman with tattooed calf muscles descending stairs, rapidly moving lips – ‘You’re not going to suck on those, are you?’

He stubs out the butt, satisfied he got one in.

I wonder when he’ll light another c-stick, whether he’ll ever get out of jail.

My wife and I zip, button, brush, and pack. We walk to bus stop, daughter in stroller, where we shiver and wait in cold drizzle.

There is a clear, assignable cause why the bus is late.

I also know that if I take a twenty-metre walk to the 711 to buy an iced caramel donut, the bus will suddenly arrive –out of nowhere.

JEREMY ROBERTS

PUBLISHED SEPTEMBER 2024, ARDEN

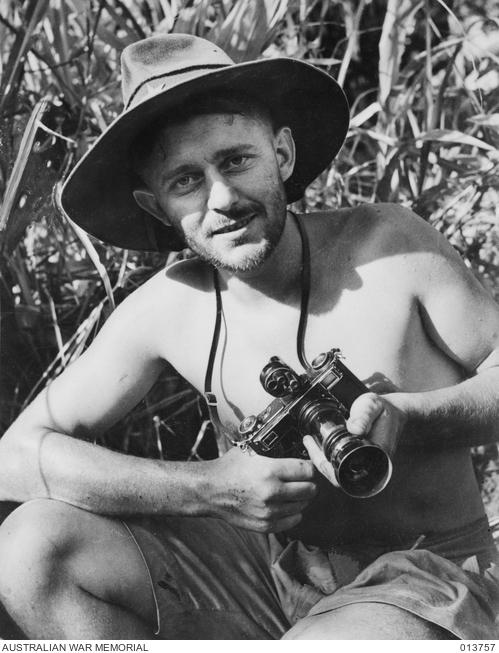

‘With The Buna Shots, Stephen Dando Collins reminds us of his pedigree as the foremost reporter of wartime history. He takes us into the battles of the war in New Guinea and into the lives of those involved, most noticeably, photographers George Silk and George Strock. A brilliant book that left me wanting more from this writer of great note.’

GREG T ROSS