25 minute read

rm in Amsterdam and Jakarta 3 At the offi ces of the architecture fi

3 AT THE OFFICES OF THE ARCHITECTURE FIRM IN AMSTERDAM & JAKARTA

Eduard Cuypers: young and promising

Amsterdam: 1872-1878: From Roermond to Amsterdam

Born in Roermond in the southern part of the Netherlands on April 18, 1859, Eduard Cuypers completed his schooling in 1875. 1 When not at school he was a regular visitor at the workshop of his uncle P.J.H. (Pierre) Cuypers (1827-1921). Although his uncle moved to Amsterdam in 1865, he kept his workshop in Roermond for the production and restoration of church sculptures. Pierre Cuypers had steady work and took on an average of fi fteen new construction projects annually, especially in Germany. He travelled back and forth a lot between Amsterdam and Roermond and frequently visited his clients, to monitor progress on the construction site. From 1874 onwards, Pierre Cuypers worked annually on more than fi fteen new churches, mainly in the Netherlands. He designed in neo-gothic style, his signature style. A year later Pierre Cuypers received two important assignments in Amsterdam: Central Station and the Rijksmuseum. Pierre owed these secular building projects to his brother-in-law, Joseph Alberdingk Thijm and his friend and government advisor Victor de Stuers. Both used their favourite neo-Gothic exclusively. They regarded it as the only answer to classicism and other imitations, and they would also like to fi nd this architecture in government buildings. For fear that those buildings would become too neo-gothic, read too Catholic, many architects opposed these assignments. Young Eduard must have noticed that opinions about architecture can be quite divided. Diff ering opinions also came to the forefront in the Architectura et Amicitia Society (A et A) in Amsterdam, where P.J.H. Cuypers was an honorary member. Eduard Cuypers moved with his parents and three sisters to Amsterdam in 1876, where he could follow his uncle closely. He must have identifi ed less with the world view of his uncle, grafted on the Catholic Church and the Middle Ages. He was for renewal. On January 13, 1877, the fi rst of 8,000 poles went into the ground for the Rijksmuseum. To allay fears that it would become a typical Catholic building, Pierre Cuypers chose to use sculptures and ornaments from Dutch history. He set up a workshop for this purpose in a shed on the construction site. Pierre needed, as he said, ‘young people who are going to carry out the decorations on the building, in the fi rst place sculptors’. Eduard also went to work there and had to work strenuously, as he said later. He could not sculpt himself, but made sketches, drawings and building plans, that appealed to him, as did the organisation around it. It is possible that he met Marius Hulswit on the construction site, who was then the 15-year-old son of an Amsterdam apothecary. 2 Eduard observed the building process. He may have been involved in the discussions about the most ideal light in the museum, because he later devoted much attention to light in his designs. 3 He set aside part of his earned money to set up his own architecture fi rm Eduard, unlike his uncle, was open to the latest developments in architecture. 4 For that reason, he spent a great deal of money on books and international journals in the fi eld of architecture. 5 In 1878 he became a member of the architects’ association Architectura et Amicitia (A et A). His uncle may have recommended his young cousin. Perhaps Eduard travelled to Paris that year to get inspiration at the World’s Fair, but also to see a city that must have fascinated him. Paris was a city full of new construction in the style of the French Renaissance and classicism.

Amsterdam 1879-1884: ‘Family is family’

In 1879 Eduard worked on the construction of the fi rst American Hotel in Amsterdam, the predecessor of the present one. His father also contributed to this as a decorative painter, by applying the coats of arms of the various American states on the ceilings. In 1879, Pierre Cuypers’ workshop on the building site of the Rijksmuseum was formally converted into the drawing school for art crafts ‘Kunst-Nijverheid-Teekenschool Quellinus’. Here Eduard followed an architectural training. Hereby he obtained access to the necessary papers to start his own architecture fi rm. In 1881 he began working as a small independent entrepreneur using the name Ed. Cuypers, in order to avoid confusion with the offi ce of his uncle Pierre. He designed a representative façade for the Rondeel Hotel in Amsterdam. ‘The façades were erected in the style of the new

Amsterdam, Hotel Rondeel designed by the 23-year-old Eduard Cuypers. ‘The façades have been erected in the style of the new German Renaissance’, according to the Algemeen Handelsblad on September 6, 1882. ‘The decoration includes seven medallion busts of famous world travellers’ saa

Amsterdam, the offi ce stamp hni-croi

Amsterdam, the fi rst American Hotel on the Leidseplein co-designed by the 20-year-old Eduard Cuypers, who made this drawing saa, atlas kok xxix-084

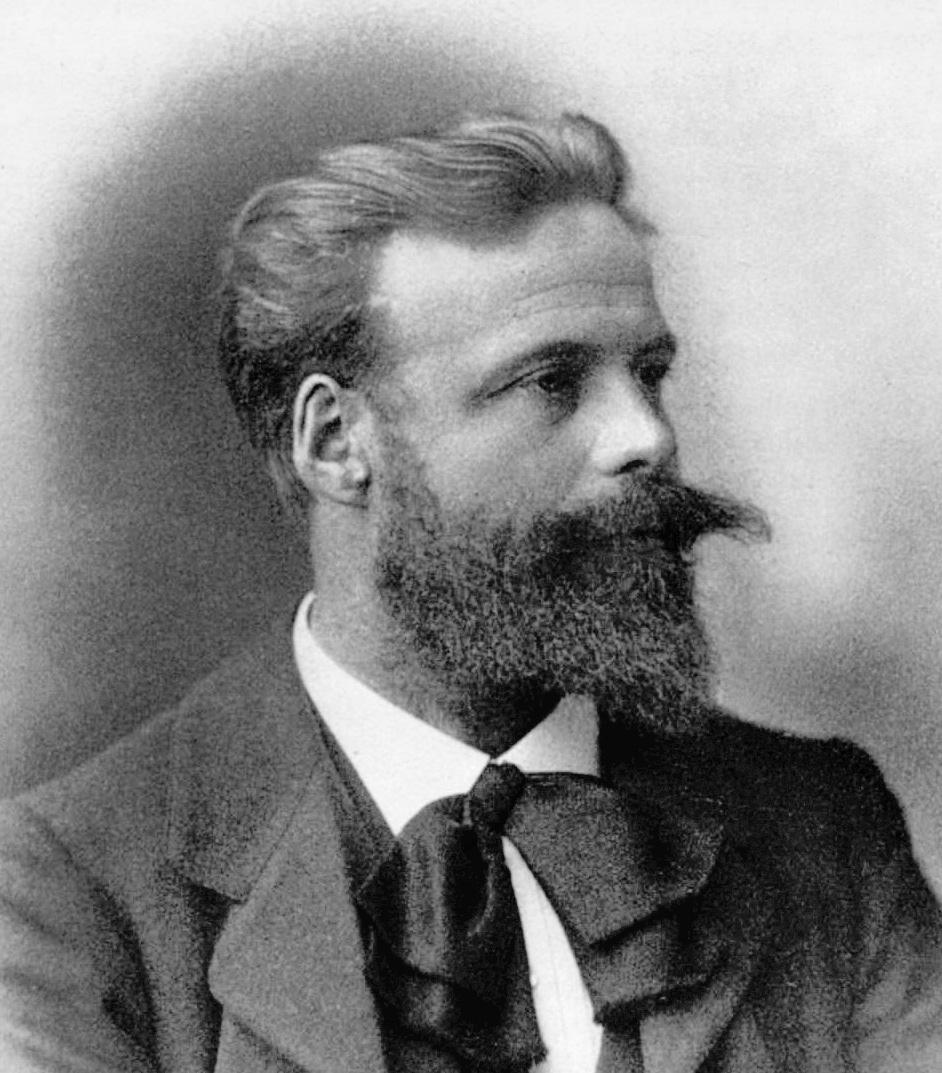

Amsterdam, Eduard Cuypers, older than thirty-fi ve years saa gerlagh 2007 p. 134

German Renaissance’, according to the Algemeen Handelsblad newspaper, ‘The decoration includes seven medallion busts of famous travellers’. ‘The models are supplied by the sculptors Van den Bossche and Crevels, two highly talented young artists, according to the newspaper. Both would soon break through as the two best-known sculptors in the Netherlands. 6 Eduard received another commission in Amsterdam, Maison Stroucken. He designed the banquet hall and gave the façade something theatrical in a variant of the French Renaissance. ‘No expense has been spared to make it pleasant and comfortable for visitors. That this honours the young architect, everyone will agree with us, ‘wrote a journalist. The building is now part of the renewed De Lamar Theatre. Because the renaissance styles gave him little design space, Cuypers soon turned to eclecticism. This is not so much a building style as a design rule-free method that could be free and decorative. He must have experienced this as very liberating. 7 He allowed his client to decide on the style, neo-Renaissance, classical, or eclectic. He aimed at a diff erent market segment than his uncle with the emphasis on private houses, hotels and restaurants, building types where the personal wishes of the client played a prominent role. This meant that he was not in competition with his uncle and that he could even hope that his uncle referred clients to him. Eduard was himself diff erent from his uncle, who mainly positioned himself as a master builder

Amsterdam, Maison Stroucken designed by Eduard Cuypers saa, gerlagh 2007 p. 139

and, above all, as an expert, as someone who knows what is good for a client. 8 As with many other architects, Pierre Cuypers referred to knowledge and insights that were documented in manuals. Eduard, on the other hand, wanted to create a relationship with the client as a starting point for his design. He presented his client with examples from books and recently published international journals. His orientation was international. He attached great importance to applying the latest techniques. ‘Hundreds of people used the new lift in the’ American Hotel ‘on the Leidseplein during both Whitsun days’, according to the Algemeen Handelsblad on May 31, 1882. Presumably, the 23-yearold Eduard Cuypers helped to ensure that one of the very fi rst passenger lifts was introduced in the Netherlands. Since his membership of the A et A, the social life of the Society fl ourished. He organised evenings and excursions. The ‘Rijksschool voor Kunstnijverheid Quellinus’ became a success in the meantime. The school had about sixty pupils in 1882. P.J.H. Cuypers was on the school board. The twentyyear-old Marius Hulswit taught here, fi rst in drawing and later in what was called ‘all kinds of techniques’. He did so that for at least three years. Eduard Cuypers did not allow himself time for such an activity. He preferred to put all his energy into his own architecture fi rm. In 1882 Eduard ‘s mother died at the age of 53. He decided to move in with his father and his three

younger sisters. His architecture fi rm was at a diff erent location. Undoubtedly, he visited the International Colonial and Export Trade Exhibition, which took place in Amsterdam in 1883. There he saw for the fi rst time what the Dutch East Indies had to off er: beautiful fabrics and many arts and crafts. In 1884 Eduard became a board member of A et A. As the society’s librarian, he ensured that the small library of the society grew into a ‘visual school’ for architects. 9

Due to his enthusiasm, the number of members increased from about one hundred to about 250. In 1884, A et A relocated from Maison Stroucken, where the club was bursting at the seams, to the American Hotel. Internally there were frictions. As the construction of the Rijksmuseum progressed, the criticism increased, also on the designer P.J.H Cuypers, both within A et A and nationally. Although Eduard’s architecture had taken a diff erent path, he kept himself out of the discussions. Family is family.

Surabaya 1884: A return trip to Surabaya

Marius Hulswit sailed to the Dutch East Indies in April 1884 to start a new life there. 10 But in December of the same year he sailed back with his future wife, a Dutch woman, whom he had met in Surabaya. She was the daughter of a contractor who had hired him. Shortly afterwards she had become pregnant by Hulswit. They travelled together to Genoa. On their way to Holland, Marius Hulswit and Johanna Merghart decided to marry in Switzerland. They travelled by train to the Netherlands where they registered in Roosendaal on January 28, 1885 as a married couple. They went to live in Apeldoorn, where their son Jan Frederik was born on April 18, 1885. 11

Amsterdam 1885-1895: Building with the latest techniques

In 1885 the opening of the Rijksmuseum took place. The Dutch king Willem III failed to attend, he did not want to go this event. Without saying this publicly he thought the building was a Catholic cathedral. A new concert hall was built in the garden behind Maison Stroucken, designed by Eduard Cuypers. In addition, Eduard provided the layout of the halls of the International Art Association, which led to a follow-up assignment, namely the design for the studio of Van den Bossche and Crevels, who become good friends of his. 12 Commissioned by Eduard, they would later make the statues and ornaments that adorn various bank buildings of the present Bank Indonesia. 13 Through them he came into contact with other sculptors, who inspired him to search for new forms of art in the style of the English Arts and Crafts, which precede those of Art Nouveau or Jugendstil. Marius Hulswit lived in Amsterdam again at the end of 1885. He worked at the architecture fi rm of Van Rossem and Vuyk. There they mainly designed utilitarian buildings with iron constructions, which made Hulswit extensively acquainted with them. Perhaps he knew about the construction of the SaintJoseph church in Groningen. The church, fairly unique to the Netherlands, featured an openwork spire of cast iron. During the construction, Father Antonius Dijkmans S.J. (1851-1922) was involved, chosen by the church administration, as supervisor. In 1889, Ed. Cuypers designed no less than four capital mansions on the Sarphatistraat. Possibly he met Marius Hulswit there, because the architects Van Rossem and Vuyk worked at the same time on the construction of an adjoining building. After completion of the Rijksmuseum, the discussions between proponents and opponents of P.J.H. Cuypers became more intense within A et A. Most members wrote him off as someone who belonged to the past. That was, in their eyes, everyone who held on to the international neo-styles. While discussing, they agreed on the idea to look for a Dutch national style. The debates also dealt with the role of technology in construction. For Eduard, the application of new techniques was self-evident. The great élan that Eduard Cuypers had brought into the Society for fi ve years disappeared through all those discussions. In 1888 he left the board of the association. He remained a member of A et A for more than 25 years, but whether he was there frequently is doubtful. 14 He may have escaped that oppressive architects’ coterie with a visit to the impressive world exhibition in Paris. In the years that followed, his offi ce produced many designs in the style of the neo-Renaissance, including that for the station of ‘s-Hertogenbosch. Its style was diff erent to that of Amsterdam’s Central Station, it was unfortunately destroyed by bombing in the Second World War. In 1892 the architectural offi ce of the 33-yearold Eduard delivered the twentieth project. The audience saw the opening of Hotel Polen on the Kalverstraat as a sensation, due to the contemporary but still extremely rare facilities such as electric lighting, central heating, a hydraulic lift and numerous telephone connections. At the same time, Berlage who was three years older and without even one building to his own name, taught at the Quellinus school. 15 The name of his predecessor Hulswit would certainly have been mentioned. Outside the school walls, Berlage held fascinating lectures about what he considered good and bad in architecture. Many young people were hanging on his every word. Eduard Cuypers was given another project. Amsterdam received another appealing building in the same year following the latest architectural developments in America. 16 At the Spui, a shop was built, which with its high windows was impressive and inviting. The furniture store Jansen received positive criticism from abroad. There was something sparkling about his concepts, which were lacking in later rationalism advocated by Berlage. 17

Amsterdam 1890, for Eduard Cuypers, the city had to be an artwork. He designed the richly decorated houses on the right in Sarphatistraat photo: g.h. heinen cra

‘S Hertogenbosch 1896, Eduard Cuypers designed the station in this city, visible in the background. Visitors were greeted with very representative and decorative buildings and Eduard Cuypers was happy to contribute con

Jakarta 1890-1895: Hulswit returns to the Dutch East Indies

On April 9, 1890, the Roman Catholic Church of Jakarta collapsed with thunderous sound. 18 Thankfully, there were no victims. The building, once a residence, was converted into a church in 1880 with a ‘fi tting front’. A new church had to be built. Pastor Dijkmans S.J., who had swapped his fi eld of work in the Netherlands in 1888 for Jakarta, started to design it himself. He drew a large neo-Gothic cathedral. Possibly he felt that Jakarta did not have to be inferior in relation to Cologne in Germany, where barely ten years earlier the impressive Gothic cathedral, after many centuries, had been completed. Although there was no money for such a large building, the construction commenced. After a few months the foundations were there, but there was no money left. The church services were forced to take place in a wooden shed specially built for that purpose. Father Dijkmans S.J. left for the Netherlands on sick leave. Money, a lot of money, had to be collected, especially in the Netherlands, to carry out the ambitious plan.

In 1893, Marius Hulswit returned to the Dutch East Indies with his wife and child, to build a new life there. The young family settled in Jakarta. Hulswit was employed by an employment agency, which leased professionals to companies. In order to publicise their activities, the fi rm regularly placed advertisements in newspapers with texts such as: ‘Our technical engineer, Mr. Hulswit, who has managed construction of large buildings both in Europe and in the Dutch East Indies, can perform all work in this area with knowledge and accuracy. Of this we can assure you’. 19 It worked. He was approached for the construction of the accommodation of the Court of Justice in Surabaya. An engineer from the Waterstaat had made a sketch plan for this. 20 They asked him if he wanted to check whether this was constructively correct, but also whether he wanted to build it. He wanted to, but not from Jakarta. On May 4, 1894 he left Jakarta and he sailed with wife, child and sister-in-law to Surabaya. 21 Presumably, his parents-in-law also suggested that he join in their family business at that time. From that moment his place of work was the Boomstraat (now: Jl. Branjangan) in Surabaya. Here he presented himself not only as a contractor, but also as an architect. Weekly advertisements appeared in the newspaper in which he advertised his workmanship. Meanwhile he worked together with the engineers of Waterstaat on the construction of the Court of Justice. The design was largely based on the manuals of which Waterstaat made intensive use. These were based on building practices in Europe. 22 In the Dutch East Indies, however, much had to be improvised, especially with regard to building materials, because otherwise everything had to come from Europe. In 1895, part of the roof came down during construction. 23 Inspections followed to see if the construction was reliable. 24 That was not the problem. The soil was not very suitable which Hulswit could not be blamed for. He expanded his network within Surabaya and came to be known as a practical builder. This also contributed to his involvement with the extension of the Ursuline Sisters’ building. He also presented himself as a specialist in the fi eld of plastering with portland. That made money, because almost every building in the Dutch East Indies was built using plaster because of the inferior quality of the indigenous brick. In August 1895 the Court of Justice opened its doors in an appropriate way. There was further subsidence, but that was not visible on the building as long as the seams were regularly closed with cement. Around that time, the Catholic parish in Surabaya needed a new church building, for which Hulswit made a proposal in 1896. He designed a church in Roman style and added a rough price estimate of the construction costs. In consultation with the church administration, he adapted the design, but after recalculation the plan proved to be too expensive and the execution did not go ahead, perhaps not only because of the costs, but possibly because of the architectural style. In the Netherlands and, apparently also in the Dutch East Indies, every Catholic church had to be neo-Gothic in style.

Amsterdam 1896-1897: There is more than the Netherlands In 1896 Berlage came to the conclusion that: ‘The architecture of P.J.H. Cuypers is the only one that deserves to be viewed, simply because that is the only architecture with lasting value’. 25 Eduard Cuypers’ station in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, which was completed shortly before, apparently did not deserve that attention. Berlage’s infl uence grew in the Netherlands constantly. The station was given a negative judgment by the professional world for decades. George Willem van Heukelom (1870-1952), working for the railways, made the station roof in front of the station in ‘s-Hertogenbosch. Cuypers and he worked together very well and became friends. Made curious by Berlage’s statements, they attended Berlage’s lecture to fi nd out his secret. 26 They must have discovered that Berlage’s comments on architecture were fascinating, but that he was rather compelling in his judgments. He also was calculating shortly thereafter, P.J.H. Cuypers, as councillor of Amsterdam, suggested Berlage as architect for the construction of the Stock Exchange the socalled Beurs in Amsterdam, Berlage called it an ‘immortal merit’ of Pierre Cuypers that he had ‘enabled the recovery of architecture’. 27 To interfere in discussions such as this did not interest Eduard. He did not think and did not design from the theory, but he did work intuitively. For him architecture did not belong to the pleasures that could come about through the reason. Yet Berlage aroused his admiration, if only because his view of architecture aroused debate among all his colleagues. Despite this view of Berlage, Eduard made a number of critical com

Surabaya, Court of Justice around 1930, built by M.J. Hulswit in 1895. It was demolished after major war damage con

Amsterdam, inaugural festivities in 1898 with honoured visitors from the Indonesian archipelago, including, seated from left to right: Amidin Pangeran Mangkoe Negoro, son of the Sultan of Kutai, Pangeran Ario Mataram, brother of the Sushuoenan of Surakarta, Jang di Pertuwan besar Sjarif Hashim Abdul Djali Saifuddin, Sultan of Siak, Hassanmudin Pangeran Sosro Negoro son of Sultan of Kutai. Standing from left to right: Raden Mas Aryo Kusumowinoto of Surakarta, Guards Mas Pandji Puspo Atmodjo of Surakarta, Raden Mas Matthes, son of the Pangeran Ario of Mataram gedenkboek 1898 p. 313 ss

ments in 1896, and commented publicly, on the design of the Beurs presented by Berlage. 28 His objections mainly concerned the façade at the Damrak side of the building in Amsterdam. He found this façade design much too closed and therefore downright unkind in terms of experience. Moreover, he regarded it functionally as very illogical that the public entrance was visibly more important than access for traders. Berlage did not agree and neither did the client, the municipality of Amsterdam. Since then, Cuypers refrained from commenting on other people’s work, while most colleagues increasingly made a habit of it. For example, the city of Amsterdam introduced a regulation in 1899, which stipulated that the architecture of a building fi rst had to be approved by the municipal council. Only then did the municipality sell the building plot. This must have been experienced by Eduard as curtailing creativity. 29 It undoubtedly also went against his feeling that not a municipality, but that the client determined the character of a building. Cuypers must have feared that he would soon be dictated a style of closed façades with a sober character. Eduard had no interest in ‘walls that completely surround you because they isolate and make you gloomy’. In his own words: ‘the cheerfulness of a room or a building is in the closest connection to the number of openings that it possesses’. 30 At a meeting of the ‘ Maatschappij ter Bevordering van de Bouwkunst’ (Society for the Promotion of Architecture) he spoke excitedly about his most recent building, the Amsterdamsche Bank on the Herengracht in Amsterdam. Enthusiastically, he showed his colleagues the building after the meeting. The façade on the Amsterdam canal was transparent with high windows and was in a cheerful Tudor style with a touch of Art Nouveau here and there. 31 Eduard’s source of inspiration consisted of a mix of innovative infl uences from England, France and Belgium. Later reactions from colleagues showed that both Art Nouveau and the Arts and Crafts from England were dismissed by many as ‘sickly, unnatural and un-Dutch’. 32 They found the bank building not rational and not ‘Dutch’ enough. They pointed to the national building tradition and a national style. In architectural education also, ‘a search for an original and contemporary Dutch beauty’ took place with the underlying goal of fi nding its own style. Eduard ignored these attempts to reduce architecture to one or two styles. He preferred to concentrate on developments abroad. Because of his involvement in the construction of the Dutch pavilion at the exhibition in Brussels in 1897, he must have come into contact with foreign colleagues. 33 That will have prompted him to look for it especially outside Dutch borders.

Amsterdam 1898: Amsterdam looking festive

In 1898 the inauguration of the Dutch Queen Wilhelmina took place in Amsterdam. The Rotterdamsch Nieuwsblad of September 5 reported: ‘The festive decoration of the arrival

Amsterdam, the ‘Amsterdamsche Bank’ designed by Ed. Cuypers in 1897 with a completely open, imaginative façade. The building was demolished in 1966, even though the city only owned one such special building saa

Amsterdam, after the inauguration of Queen Wilhelmina cra ss nieuw

Amsterdam, the ‘Nederlandse Bank’ (Dutch Bank) festively decorated on September 6, 1898 photo j. olie saa

route is designed by the architects Ed. Cuypers and W. Kromhout. The part that Mr. Cuypers designed personally is truly festive, light and colourful [...] Mr. Cuypers did not need triumphal arches. High poles, widened at the foot by a square shell painted in light colours. Here and there the poles along the centre have been widened with fl ower baskets. On the Frederiksplein there are masts around the large fountain, from which curls jump in asymmetrical, pleasantly modern style and carved from thin wood painted in light colours’. The newspaper continued: ‘The golden carriage was the most talked about. This ‘tribute from the Amsterdam people to Her Majesty Queen Wilhelmina’ was on display in the Paleis voor Volksvlijt’. The sculpture on the carriage was by Van den Bossche and Crevels, with whom Eduard maintained a friendly bond. The paintings on the carriage show residents of the the Indonesian archipelago, who bring a tribute to a European-looking dignitary. The young queen got written congratulations from: the Susuhan of Surakarta, the Pangeran of Pakualaman and the Sultans of Yogyakarta, Mangkunegaran, Sambas, Riouw, Pontianak, Langkat, Siak and Deli. Some royalty had come over and were received with many others in the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam. Eduard Cuypers, who came here regularly as concert-goer, had redecorated the big hall for this occasion. The visitors were impressed by the result. At his architectural fi rm, he and his men worked on plans for four villas, including the house and the adjoining architect’s offi ce for Eduard himself. Beside the architect’s house the building also off ered space for the architecture fi rm, several showrooms and a studio and living space for employees such as Joan Melchior van der Meij (1878-1949) and Michel de Klerk (1884-1923). 34

Surabaya 1898: Berlage also knows better at a distance

Marius Hulswit suff ered many setbacks in Surabaya. His wife was probably admitted to a mental institution. From the board of the Catholic Church he heard that his colleague W. Westmaas (1848-1914) from Semarang was commissioned to build the new church of Surabaya. Westmaas produced a neo-Gothic design and the budget was approved. Hulswit was awarded a project to build an offi ce building on the Willemskade (now: Jl. Jembatan Merah) in Surabaya for the life insurance company ‘De Algemeene’. His design was sent to the head offi ce in Amsterdam for approval. It took a long time before he received a response because Berlage was also asked for his opinion. 35 Berlage rejected it. In a letter to the client he wrote: ‘the design is that of a villa-like shophouse designed by a small architect. It is this architecture that has made our beautiful cities and towns ugly.’ 36 He was later to repeat these words at a lecture. Hulswit made a new design, which was again subject to Berlage’s judgment. He remained dissatisfi ed and now started to draw it himself. He adopted the design of Hulswit and mirrored the façade, creating symmetry. This doubled the building in width. In the high cowl he incorporated several work areas, which was unusual in the Dutch East Indies: a roof was there only for ventilation. 37 . The architect Charles Wolff Schoemaker (1882-1949) later called the building ‘completely unsuitable for the tropics’. 38 As a consolation, Hulswit was told that he could be the supervisor at the construction site. The company J.E. Scheff er became the contractor. 39 With Berlage’s design almost all building materials had to come from the Netherlands. Hulswit had a hard job on his hands as site supervisor. Fortunately, there was better news from Jakarta. 40 On the basis of an approved cost estimate, he was allowed to complete the new Catholic church there. 41 The basic design did come from the aforementioned pastor Dijkmans, but he had fi nally left for the Netherlands. The foundations were now hidden under overgrown vegetation, but funds were suffi cient. Hulswit decided to move to Jakarta and sold, as was customary in the Dutch East Indies, his household eff ects on a so-called ‘vendutie’. He sent his 13-year-old son by boat to the Netherlands. 42 Jan Frederik grew up with his uncle and aunt. Hulswit entrusted his company to a partner, with the consent of his in-laws, who still participated fi nancially. Perhaps he did not rule out that he would return to take it again. Without the involvement of Hulswit, the contractor Scheff er fi nished the design of Berlage, based on that of Hulswit, at the Willemskade (now: Jl. Jembatan Merah) in Surabaya.

Jakarta 1899: The cathedral is completed

The construction of the cathedral in Jakarta underwent a veritable restart in 1899. Hulswit selected the people who could do the job. He worked with them as his teacher P.J.H. Cuypers had done during the construction of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. During the construction of the church he met a new love, Elize Karthaus (1880-1930), a woman from a wealthy family. In Surabaya, his fi rst marriage was formally dissolved. 43 Shortly after, the couple became engaged. 44 Hulswit came in contact with pastor M.J.D. Claessens in Bogor. With him he arranged that the older boys at the Vincentius Institute could make the church furniture in his workshop, which he arranged there. He also worked on the new building for this institute. The plans were already fi nalised and had been drawn up by the architect Van der Ploeg who died suddenly. The fi rst phase of this building was completed on February 15, 1900. Hulswit followed the plan of Father Dijkmans for the cathedral with the exception of the spires. Hulswit opted for cast iron. He made the drawings for the spires, which went to Europe by ship, to be manufactured there. A few months later the spires arrived by ship in parts in Jakarta. All parts of each tower peak were hoisted about fi fty meters high along bamboo scaff olding. 45 At that height they were assembled.