REPOSitioning balenciaga

This report gives an insightful view of the current challenges Balenciaga faces in terms of regaining its devoted consumer base, resonating with a diverse selection of segments particulary Generation Z and repositioning itself to a growing Middle Eastern market. Firstly, a rationale will be developed using relevant theories to acknowledge Balenciaga’s illnesses and then to prescribe solutions. The growing need for touch and integration of virtual and reality has caused Balenciaga’s urgency to change; the Armstrong-Gibbs and McLaren (2017) brand equity model has provided a framework for this report to follow to show how Balenciaga can restructure its product-centric business model to one that embodies the consumer. As part of the rationale which links to the further recommendations is the suggestion that the flagship store in London moves location in order to resonate with Gen Z consumers, showing that Balenciaga’s repositioning to different geographical areas can have a positive impact. Secondly, creative recommendations have been pitched that include the collaboration between Balenciaga and the Museum of the Future which will allow flagships stores to become an experience rather than just a point of sales. Other recommendations enhance the post-purchase experience for consumers, such as the app membership, physical magazine and personalised clothing to create a brand at home not only in-store.

A dynamic mission to deliver craftmanship through creativity, with the ultimate ambition to be the world’s most influential

luxury group, Kering captures the current and future zeitgeist (Kering, 2022). The elevated consumption of fashion has manipulated consumer beliefs between their actual needs and wants, made possible through Kering’s strong marketing strategy (Hameide, 2011). The fusion of corporate brands and independent brands together has exposed the group’s presence onto the high-end fashion and haute-couture market, encouraging consumers’ eager appetite for more (Hameide, 2011; Posner et al, 2015). In this instance Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (1943) could be argued that in today’s ‘always on’ society consumers have easy access to their desires before deficiency needs are met. A McKinsey report (2020) shows that Generation Z consumers look beyond the tangible products but consider the brand equity as a more important reason to buy (Armstrong-Gibbs and McLaren, 2017).

Balenciaga, one of Kering’s houses, considered one of the most influential brands of this generation exhibits unconventional ready-to-wear structures laced with hautecouture silhouettes, yet how does this superiority trickle down to the mass markets (Solca, 2022)? If Gen Z consumers drive the change and expectations in the fashion industry, Balenciaga needs to reposition itself to a market that resonates with a younger generation (McKinsey, 2020). Kering’s vision elaborates that it enables individuals to be artistic, bold, and free: consequently, this report will challenge that declaration using Balenciaga as a focus to make that vision accessible for everyone (Kering, 2022).

Balenciaga’s breakdown, regarding its advertising scandal, has urged the brand to take into consideration public sensitivities when releasing controversial marketing campaigns, with demand for the brand declining already, Balenciaga need to avoid the long-lasting backlash like that of Dolce and Gabbana due to its racial insensitivity (Williams, 2022). Using the Armstrong-Gibbs and McLaren (2017) brand equity model, Balenciaga’s current position and the necessary actions it needs to fulfil to establish salience with its core consumer will be developed. Once the go-to brand for edgy accessories and clothing, Balenciaga’s tainted brand values have caused conflict for many of its “luxury gourmands” (those who completely dress in designer daily) and discouraged the “luxury nibblers” (those who rarely buy luxury items, only usually as a reward) to buy from Balenciaga at all (Seo and Buchanan-Oliver, 2014). To regain its customer base, in particular Generation Z which have thrived off the democratisation of luxury, Balenciaga must build its brand equity firstly with salience, emphasised by the performance and the imagery of the brand, the feeling and judgement it alludes, to finally demonstrate resonance (Armstrong-Gibbs and McLaren, 2017). In order to do so, a shift from the outdated product-centric business model to a customer-centric one would create an ideal brand, Balenciaga’s focus on previous profitable products has overlooked the future needs of its consumer causing marketing myopia (D’Arienzo, 2016; Gupta and Ramachandran, 2021). To secure relevancy, Balenciaga must now consider the customer’s experience pre-purchase, during, and postpurchase with a focus on the sensory stimuli in all areas, the brand touchpoint wheel has exposed Balenciaga’s missed opportunities in its advertising, point of purchase displays, loyalty program and customer services, therefore it should be used as a catalyst for Balenciaga’s crisis management (Peirson-Smith, 2021).

A new generation of subversive, experimental consumers have questioned industry standards regarding communication and engagement strategies, that connect the brand to the consumer emotionally, instigating Balenciaga’s need for change (Piancatelli et al, 2020). Postpandemic, hyperphysical retail atmospherics create a memorable and engaging experience for Gen Z consumers, 56% of which go to brick-and-mortar stores for fun, a direct reaction to the metaverse paradox (Chitrakorn, 2022; Illenberger, 2022). The physical and environmental characteristics of a store enlighten customer’s five senses, by delving into the deeper atmospherics of the lighting, music, and temperature, Balenciaga have the opportunity to connect with consumer feelings on a higher level to reach ultimate brand loyalty (Xu and Nuangjamnog, 2022; Chitrakorn, 2022). Balenciaga’s raw architecture aesthetic provides a visual brand identity throughout its stores, faded graffiti obscuring distressed exteriors, dim lighting filtering across abandoned spaces consistently reinforces the brand’s eccentric personality (Hameide, 2011; Parkes, 2021). The current aesthetic environment within Balenciaga stores lacks the ability to develop a customercentric approach, due to the dissonance of haptic ques, consumers’ need for touch to validate a purchase is overwhelmed by the solitary surroundings (Peck and Childers, 2003; Manlow and Nobbs, 2013). How a brand

perceives itself doesn’t always correlate to the consumer: over 80% of millennials and Gen Z consumers said their shopping habits would change if they felt more emotionally attached to a brand through an immersive experience instore, yet Balenciaga’s brand identity causes a detachment issue for many (Hameide, 2011; Buller and Scott, 2022). Using the Peck and Childers (2003) Need for Touch Scale (NFT) it shows there is two types of consumer; one that has enjoyment through direct contact with products (Autotelic) and one that has a need for information from a product’s physical characteristics (Instrumental), both of which Balenciaga need to consider to resonate with a wider audience. Balenciaga have a brick-and-mortar presence that compliments its ecommerce site, allowing consumers to identify risks by evaluating the product pre purchase, using tactile input leads to a guiltfree purchase decision (Manzano et al, 2016). But in today’s society how a product feels are not the only selling points for a consumer, moral guilt and social responsibility guilt are considered when making a luxury purchase which is evident in the decline of Balenciaga products since the advertising controversy, because it violates one’s moral values or social commitment (Ki et al, 2017). The brand management table by D’Arienzo (2016) >>

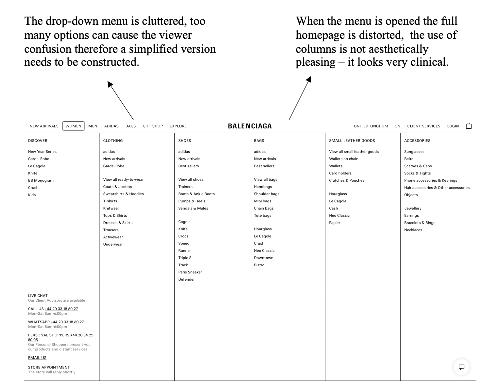

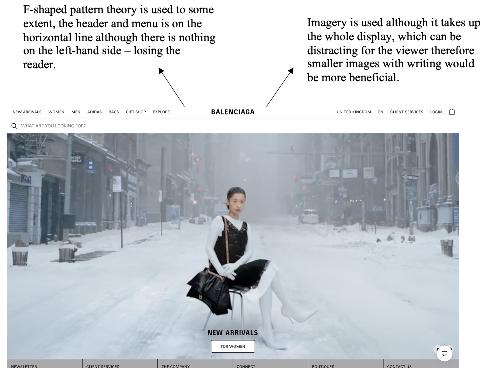

>> mirrors the dishonest and corrupt illness Balenciaga has, with a prescription that is based solely around the consumer, the instore experience must emulate the tactile, auditory, and possibly olfactory senses to over-deliver customer satisfaction (Hong, 2022). For a brand like Balenciaga, its economic gain is the most important element of the triple bottom line to succeed in, therefore the amplification of store atmospherics to fulfil hedonic motivations that impulse irrational buying is in the brand’s best interest (Foster and McLelland, 2015). Traditional retail landscapes have changed, with further penetration of e-commerce in the luxury sector Balenciaga’s online existence must match the customer-centric approach that is needed in-store as well (Sabanoglu, 2021). The digitalised world has seen emerging technologies such as 3D content and virtual reality provide a seamless customer experience enabling enhanced product viewing and interactive interfaces reflecting a level of luxury, yet Balenciaga’s version of luxury has turned to digital chaos (Kim, 2019). The brands sudden loss of acceleration could be caused by the conflicting online and in-store presence, the website is cluttered with no clear direction or omnichannel integration, but the product layout instore is distant and uninviting, disengaging consumers from the brand values (D’Arienzo, 2016). (See appendix one for an annotated Balenciaga homepage.) Balenciaga’s e-commerce site alongside its social media platforms is the first destination for consumers pre-purchase, therefore it is crucial that the marketing is aesthetically pleasing, attention-grabbing and most importantly gives off a message that resonates with the consumer (Armstrong-Gibbs and McLaren, 2017; Vempati et al, 2020). Balenciaga’s inconsistent channels have left consumers with a judgement that the brand itself is confused, but an omnichannel approach and/or integrated retail strategy would cause clarity and satisfy the growing needs for a combined physical and digital world (Alexander and Alvarado, 2014; Armstrong-Gibbs and McLaren, 2017). Through experiential marketing in terms of interactive displays created by artificial intelligence, opulent décor that suggests a sense of luxury and product varieties that resonate with younger consumers, Balenciaga could create a flagship store that embodies the full essence of its brand identity. If Kering’s vision is to enable individuals to be bold and artistic, then Balenciaga need to shift its hostile and cold store conditions to a space that offers multisensory opportunities and digital co creation (Spena et al, 2012; Kering; 2022).

The flagship store in London is housed on New Bond Street: out of the three stand-alone stores in the city this one arouses the London brutalism scene the most, which is obvious through the progression of Demna’s influence (Arrigo, 2015) (See appendix two for primary research on how Balenciaga’s flagship store made a Gen Z consumer feel.) The purpose of a flagship store should be to strengthen the link between the brand and the consumer, by viewing the store as a product or a publicity vehicle rather than a service creates tangibility for the consumer through the advertising and promotion within that space (Moore et al, 2010; Arrigo, 2015). The expression “the language of the flagship” embodies the full experience that the consumer endures, from the standard of service, the visual impact of the store and the geographical location it is placed (Arrigo, 2015). Luxury stores on New Bond Street (Mayfair) have on average 230 metres between them to reinforce the prestigious nature of the brands, although for Balenciaga this agglomeration can cause confusion and ultimately for consumers too, enabling a downturn of resonance (Armstrong-Gibbs and McLaren, 2017).The store is located just across from Chanel and Dior, yet Balenciaga’s brand values and identity differ from the two haute couture houses which alludes the question of whether the flagship store should be in a different location. Soho, only the next neighbourhood along from Mayfair, has a history of representing a refuge for people who felt lost within their society; with the explosion of drag culture, house music and drugs everyone felt some kind of freedom in Soho (Figueredo, N/A). Looking at how Balenciaga resists societal norms through its experiential clothing and advertising, Soho would be the perfect location in London for a flagship store to represent the younger Balenciaga consumer (Figueredo, N/A). Soho plays host to a variety of consumers but more specifically youth culture, looking to evoke their feelings through fashion, art and music, Balenciaga’s future repositioning between middle market and high-end fashion would resonate with the Soho cliental, leading to a higher economic gain (White, 2013; Armstrong-Gibbs and McLaren, 2017).

Yet the Balenciaga store represents the opposite, alluding connotations of ruggedness or rejecting societal norms.

This picture of New Bond Street represents the ideology of sophistication and luxury.

Clothing stores in Soho which have the same creative personality as Balenciaga.

This picture of New Bond Street represents the ideology of sophistication and luxury.

Clothing stores in Soho which have the same creative personality as Balenciaga.

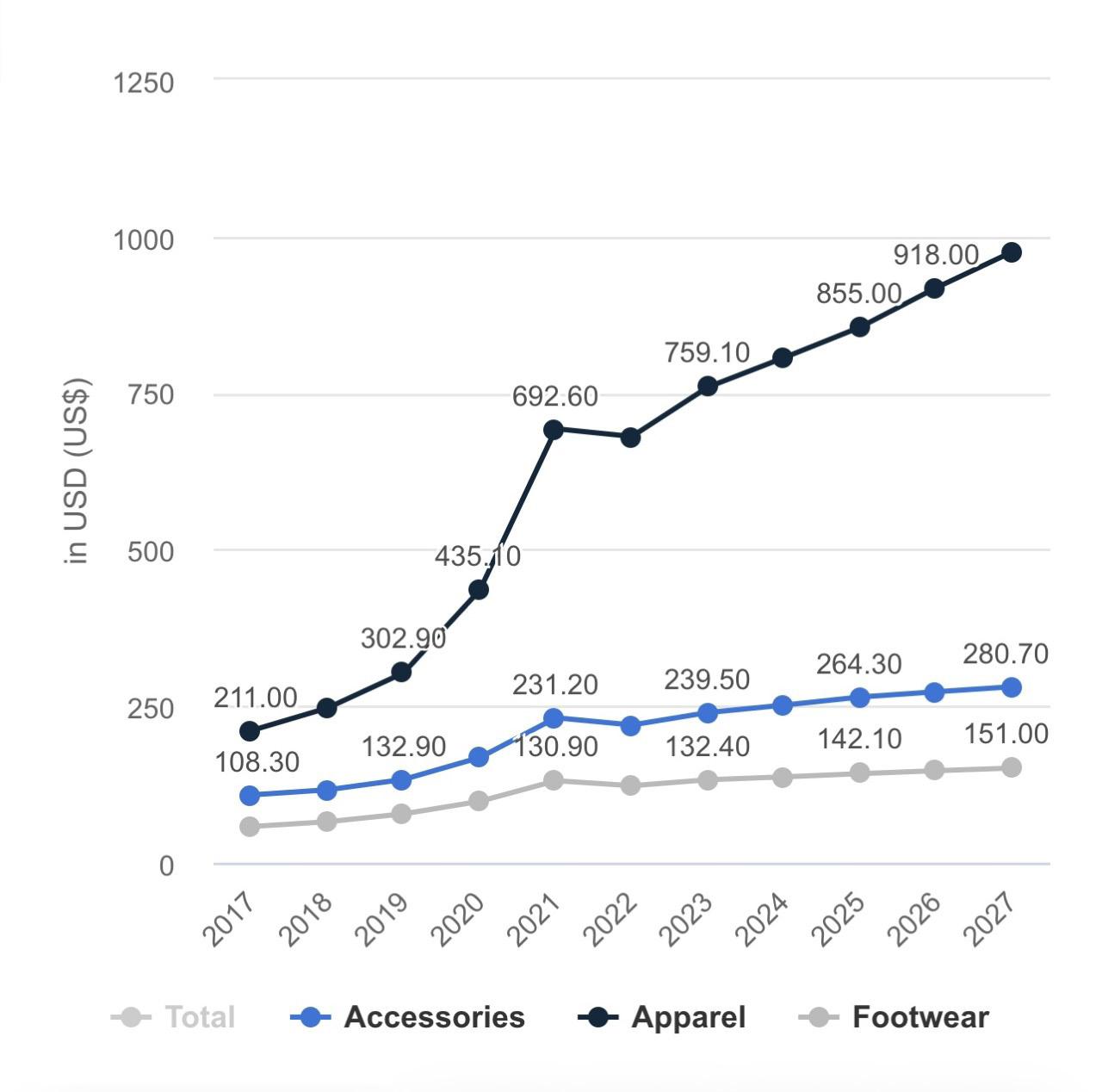

Average revenue per user by segment in The United Arab Emirates.

standard retail experience structure

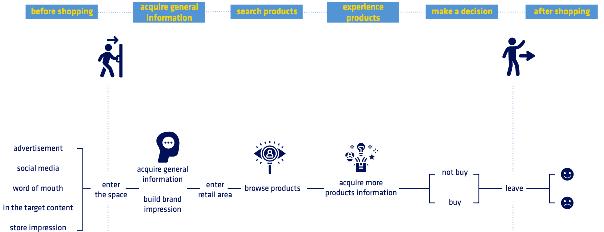

User experience journey of a smart retail space, showing that an integrated virtual world leads to higher consumption and brand loyalty (Barbara and Ma, 2021).

Balenciaga’s consumer demographic is predominantly based across Western Europe, the USA, and parts of Asia, yet the opportunity for growth in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is vast due to the geographical region that thrives of high purchases, high income, and the shift in attitude towards fashion for women (El Sawaf, 2015). Dubai is a key economic hub, a benchmark between the energy crisis in Europe and the fall in China, providing consumers with a new luxury Balenciaga can recall its challenging Gen Z consumer base by a revamped positioning in the Middle East (Mira, 2021). A recommendation for Balenciaga to restore salience and to enable Kering’s vision to be bold and free for everyone is to collaborate with The Museum of the Future based in Dubai, brands need to be more creative and digitally diverse in 2023 therefore this collaboration would set Balenciaga above the rest (Armstrong-Gibbs and McLaren, 2017; Amed et al, 2022). This partnership would allow Balenciaga to gain a benefitted brand awareness in an emerging fashion market, to build trust by directly accessing another consumer base and to show a new level of maturity as a luxury brand (Mrad, 2019). The Museum of the Future encapsulates the pressing challenges faced by society and the planet in an immersive experience fuelled by virtual and augmented reality, consequently showing visitors how this technology can be used to overcome the present and future problems (Sacheti, 2022). As previously mentioned, social responsibility guilt is taken into consideration when making a purchase therefore the collaboration between Balenciaga and The Museum of the Future would show Balenciaga’s efforts to overcome its previous issues by pledging sustainability that attracts environmentally conscious consumers (Ki et al, 2017; Sacheti, 2022). The implementation of this collaboration would be seen across all flagship stores, currently Balenciaga’s retail spaces are product-orientated but using the technologies developed in The Museum of the Future a smart retail space would be created, allowing consumers to access the brand in real-life and virtually (Park et al, 2006). The aim of this collaboration is to transform Balenciaga flagship stores into an exhibition, where consumers can endure all types of experience; entertainment, educational, aesthetic and escapism that can create memories with the brand to ensure trust (ArmstrongGibbs and McLaren, 2017; Barbara and Ma, 2021).

Employing a museological narrative would allow Balenciaga to retain its heritage instore as the simulated exhibition acts as a storyteller to the consumer; the history of Cristobal Balenciaga to the cultivating creative director that is Demna Gvasalia would be shown through a series of movable walls and displays that change in intervals (Bertola et al, 2016; Victoria and Albert Museum, 2017). Through an osmosis of ideas between The Museum of the Future and Balenciaga, a customer-centric store can be created that utilises digital systems such as facial recognition, cloud shelf and an immersive augmented experience to ultimately gain brand loyalty and resonance (Bertola et al, 2016; Armstrong-Gibbs and McLaren, 2017; Barbara and Ma, 2021). By integrating the history of Balenciaga with the future of technology enables a higher level of differentiation to consumers, an intensification of senses conveys a degree of authenticity to connect with consumer feelings to allow self-identification with the brand (Comunale, 2008; Barbara and Ma, 2021). Balenciaga’s illness of a disconnection between its autotelic and instrumental consumers can now be cured, the exhibition arouses sensory stimulation and hedonic interactions allowing an autotelic consumer to stay in-store for longer, leaving with positive sensory feedback (Jin and Phua, 2015; D’Arienzo, 2016). Due to the integrated virtual world in-store through the collaboration with The Museum of the Future, enables instrumental consumers to search for haptic information more easily using smart shelves that provide information about products, smart mirrors, and smart fitting rooms to gather a final judgement before purchasing (Jin and Phua, 2015; Armstrong-Gibbs and McLaren, 2017; Barbara and Ma, 2021).

The term ‘economy of experiences’ embodies the strategies used to create an emotional bond between consumer and company, so a recommendation for Balenciaga’s e-commerce site to match the experiential in-store presence is to create a lifestyle hub (Alexander and Blanquez-Cano, 2020). Traditional loyalty schemes include high discounts and promotional offers although this type of customer service would not suit Balenciaga’s overall business model, a paid membership plan that offers either a luxury or premium service would add value to the brand and the consumer (Stone et al, 2004). Balenciaga currently do not have a downloadable app, but by expanding the brand’s online presence would allow targeted consumers on the paid plan too access the online magazine, exclusive interviews and specific imagery creating an emotional connection (Comunale, 2008; Dauriz et al, 2014; Armstrong-Gibbs and McLaren, 2017). Consumers would be able to access their chosen membership plan via the app or the e-commerce site, acting as a digital business card Balenciaga’s website must compete with other luxury houses such as Chanel who currently have a ‘Chanel Inside’ section, reflecting its passionate brand storytelling (Heine and Berghaus, 2014; Kang et al, 2018).

By adopting Chanel’s innovative approach to sell its brand identity would transform Balenciaga’s product-centric website to one that represents the consumer even before they step in-store (Heine and Berghaus, 2014). A recommendation based on Burberry’s brand community project ‘The Art of the Trench’, which encouraged consumers to post in the iconic trench coat to be featured on the Burberry website, would allow Balenciaga to collaborate with its consumers and use its products such as the cagole bag to create an international community reflecting personal style (Heine and Berghaus, 2014; Lee, 2016). Chosen images would feature on the online magazine, giving Balenciaga the opportunity to regain strong brand equity through social approval and enable consumers to become part of a tribe (Armstrong-Gibbs and McLaren, 2017).

What the Balenciaga magazine front cover could look like: Image and Logo on the left created by Kimberly Martin on Canva and Word, using Photoshop to then layer the image on the right found on Pinterest.

The online magazine offers a pre-purchase brand touchpoint but what about post-purchase (Lee et al, 2013)? Beverland (2004) identifies six dimensions of luxury branding, one being brand image investments (marketing) so with the use of editorial endorsements and front-page coverage Balenciaga can use its magazine to revive the meaning of luxury whilst still being bold and creative (Moore and Birtwistle, 2005). Releasing a physical magazine alongside the online version allows the consumer to experience the brand away from the store and offline, tapping into autotelic consumers’ need for touch, reinforcing the psychological connection between brand and buyer (Peck and Childers, 2003; Armstrong-Gibbs and McLaren, 2017 ). Moeran (2006) suggested that magazines provide the connection between runway and ready-to-wear (RTW) so that consumers can buy into the latest trends at a more affordable price, which would allow Balenciaga’s magazine to influence those of a younger generation creating resonance (Armstrong-Gibbs and McLaren, 2017). Using Vogue’s duality to guide Balenciaga’s magazine enables cultural sensitivities to be taken into consideration, the magazine would operate on an international basis therefore the brand marketing communications must match the social, political, and ethical views of that specific country to resonate with the targeted consumer (Bailey and Seock, 2010; Armstrong-Gibbs and McLaren, 2017). Data from a survey based in Iran, showed that a homogeneous marketing approach was not effective in displaying a brand’s clarity or credibility, therefore a localised application of Balenciaga’s magazine to create clear signals would assist consumer’s perception process (Vaziri and Lopez-Belbeze, 2021). Moreover, the greater awareness of cultural codes that Balenciaga has consequently leads to more sales and a higher regard for the brand (Schroeder, 2009). Viewing Balenciaga as a metaphor that itself is a living thing, has proven that problem-solving solutions for its marketing illness can be treated proactively, with a newfound authenticity and uniqueness consumers can now self-identify with the brand (Comunale, 2008; D’Arienzo, 2016). (See appendix three for international Vogue examples.)

What the App front cover could look:

Each image is interactive and would take the consumer to a different section.

Balenciaga’s aim to resonate with a younger audience begins at the pre-purchase stage, with the marketing of the brand having the most profound effect on a consumer, therefore the need to modernise the logo and redirect the advertising campaigns is crucial to maintain the desirability that creates an emotional connection (Radon, 2012; Armstrong-Gibbs and McLaren, 2017). Thinking about Balenciaga’s brand values to innovate, to experiment and to dare, but to also be environmentally and socially conscious, does its current logo reflect its exciting brand personality (Aaker, 1997)? Data found by (Shaikh et al, 2006) proved that sans serif fonts have the personability traits of rigid, sad and, unattractive none of which match the ideology of Balenciaga. To change the logo altogether could be risk for Balenciaga, but to implement it on a line extension would diversify the brand away from its typical luxury gourmands and reach different segments particulary Gen Z consumers who are driving the change in the fashion industry (Seo and Buchanan-Oliver, 2014; Royo-Vela and Sanchez, 2022). Balenciaga as a luxury brand have associations with sophistication and high value, so it is questionable that a reduced price-range would have a positive impact on the brand image, but due to its current crisis the new range would show a level of social awareness (Royo-Vela and Sanchez, 2022). The new logo created on Canva is made up of 3D liquid chrome letters, mirroring the space-junk silver, modern armour and otherworldly remix trends that are currently storming the fashion industry, instantly connecting Balenciaga’s innovative brand values to Gen Z’s needs (Collins, 2022). The fashion industry is facing instability from all angles, but a range of clothing (incorporating the new logo) at smart price-point aimed at Gen Z consumers would create an outlet for escapism at a time of political upheaval (BOF, 2022; Collins, 2022; Kent, 2022). The new logo would feature on a range of casual streetwear items, with data from a YPulse survey (2022) showing that streetwear is the number one trend Gen Z consumers are interested in, enabling Balenciaga to stay relevant and keep its original branding credentials and selling points (Khan and Beverland, 2022). The line extension with a new logo design isn’t just about the economic gain, for Balenciaga it is a sign for change that building brand equity with its consumers through its performance, feeling and, judgement should come above controversial advertising to gain media attention (Armstrong-Gibbs and McLaren, 2017).

A recommendation for Balenciaga to build upon the line extension is to allow consumers to personalise the item the new logo appears on, whether that be the placement or the colour the individual can purchase a piece of clothing unique to them (Lourenco et al, 2017). For a luxury brand Balenciaga is readily available in comparison to other exclusive fashion houses, so the ability for consumers to bespoke an item combines the craftmanship era with the mass production era inevitably showing a degree of differentiation that Balenciaga has to offer (Bougourd et al, 2007). The collaboration between Balenciaga and The Museum of the Future has exposed technologies that can be used in other siloes of the value chain, not just marketing, but also the designing of products uniting both recommendations (Oosthuizen et al, 2021). The Fourth Industrial Revolution describes the personalised customisation system in which the design sector integrates the consumer as the producer, using this development Balenciaga stores will house design workshops across its flagship stores, installing new automated direct-to-garment printers (Lee, 2021; Industry News, 2022). This real-time fashion system has allowed products to be available immediately based on what that consumer needs, previous developments from Apple and Nike have shown the advancements through laser-engraving and digital DIY shoes but with Balenciaga a whole virtual world can be made a reality (Lee, 2021). Using the new logo customisable on said streetwear items (keeping the cost down) as a starting point for the digitised change in-store, shows future opportunities for Balenciaga that include 3D body scanning technology to create personalised fits for consumers, making Kering’s vision to be bold, creative and, free accessible for everyone (Lee, 2021; Kering, 2022).

Appendix two:

How did the Balenciaga store aesthetic make you feel?

A- When you first walk in the store it feels cold and unwelcoming.

Did it make you want to make a purchase?

A- The products were spaced out and the surroundings were minimalistic which made you look more at a product, you wouldnt if the surroundings were cluttered.

How could it be improved?

A - If the store had more colours and textures it would make the consumer feel more welcomed, whilst still giving the minimalism vibe.

Appendix three:

Vogue United Arab Emirates

Vogue Sweden

Vogue International Magazine Covers- Representing Culture and Lifestyle.

Vogue United Arab Emirates

Vogue Sweden

Vogue International Magazine Covers- Representing Culture and Lifestyle.

Alexander, B and Alvarado, D. (2014) ‘Blurring of the channel boundaries: The impact of advanced technologies in the physical fashion store on consumer experience’, International Journal of Advanced Information Science and Technology, 30 (30). pp. 29-42. (Accessed: 19 November 2022).

Alexander, B., and Cano, M.B. (2020) ‘Store of the future: Towards a (re) invention and (re) imagination of physical store space in an omnichannel context’, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 55, p.101913. (Accessed: 20 November 2022).

Amed, I., Andre, S., Balchandani, A, Berg, A, and Rolkens, F. (2022) The State of Fashion 2023: Holding onto growth as global clouds gather. Available at: https:// www.mckinsey.com (Accessed: 20 November 2022).

Armstrong-Gibbs, F and McLaren, T. (2017) ‘Brand Management’, in Armstrong-Gibbs, F and McLaren, T. Marketing Fashion Footwear: The Business of Shoes. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, pp. 180201. (Accessed: 15 November 2022).

Arrigo, E. (2015) ‘The role of the flagship store location in luxury branding. An international exploratory study’, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management. (Accessed: 19 November 2022).

Bailey, L.R. and Seock, Y.K., (2010) ‘The relationships of fashion leadership, fashion magazine content and loyalty tendency’, Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal. (Accessed: 30 November 2022).

Barbara, A. and Ma, Y. (2021) ‘Extended store: How digitalization effects the retail space design’. (Accessed: 20 November 2022).

Bertola, P., Vacca, F., Colombi, C., Iannilli, V.M. and Augello, M. (2016) ‘The cultural dimension of design driven innovation. A perspective from the fashion industry’, The Design Journal, 19(2), pp.237-251. (Accessed: 20 November 2022).

Beverland, M. (2004), ‘Uncovering ‘theories in use’: building luxury wine brands’, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 38 Nos 3/4, pp. 446-66. (Accessed: 30 November 2022). BOF (2022) ‘The Best of BoF: Luxury’s Blockbuster Year’, Business of Fashion, 23 December. (Accessed: 24 December 2022).

Bougourd, J., Delamore, P., Fauvel, R.D.P., Sjoberg, A., Lindstedt, M., Matzdorf, P., Blackford, S., McGuire, M., Bradburn, R., Robinson, A. and Boussou, S., (2007) ‘Case Studies in Personalised Digitally Printed Clothing’. (Accessed: 24 December 2022).

Buller, A and Scott, S. (2022) ‘Hyperphysical Stores’, The Future Laboratory, 15 June. Available at: https://www. thefuturelaboratory.com (Accessed: 7 November 2022). Chitrakorn, K. (2022) ‘From Jacquemus to Balenciaga: Luxury Fashion Brands Go Hyperphysical’, Business of Fashion, 4 May. Available at: https://businessoffashion.com (Accessed: 7 November 2022).

Collins, J. (2022) Footwear, Accessories & Jewellery Forecast A/W 24/25: Solid Materials. WGSN. (Accessed: 1 December 2022).

Comunale, A. (2008) ‘You are who you wear: A conceptual study of the fashion branding practices of H&M, forever 21, and urban outfitters’, Journal of the Re-tail Image. (Accessed: 20 November 2022).

D’Arienzo, W. (2016) Brand Management Strategies: Luxury and Mass Markets. New York: Bloomsbury. (Accessed: 15 November 2022).

Dauriz, L., Remy, N. and Sandri, N. (2014). ‘Luxury shopping in the digital age’, Perspectives on retail and Consumers Goods. McKinsey, pp.3-4. (Accessed: 30 November 2022).

El Sawaf, R.J.O. (2015) ‘New media marketing challenges in a multicultural environment: luxury fashion brands in Dubai’ Theses, Dissertations, and Projects.

(Accessed: 20 November 2022).

Figueredo, H.G., 8.5. (N/A) ‘The Soho Scene and the aesthetic transformation in British fashion in early 90s’. (Accessed: 19 November 2022).

Foster, J. and McLelland, M.A. (2015) ‘Retail atmospherics: The impact of a brand dictated theme’, Journal of Retailing and consumer services, 22, pp.195-205. (Accessed: 19 November 2022).

Gupta, S. and Ramachandran, D. (2021) ‘Emerging market retail: transitioning from a productcentric to a customer-centric approach’, Journal of Retailing, 97(4), pp.597-620. (Accessed: 15 November 2022).

Hameide, KK. (2011) ‘The Branding Process Phase One: The Brand Decision and Positioning’, in K.K. Hameide. Fashion Branding: Unraveled. London: Fairchild Books, 36–75. Bloomsbury Fashion Central. (Accessed: 6 November 2022).

Heine, K. and Berghaus, B. (2014) ‘Luxury goes digital: how to tackle the digital luxury brand–consumer touchpoints’, Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 5(3), pp.223-234. (Accessed: 30 November 2022).

Hong, N. (2022) ‘The Impact of Senses on Purchasing Decisions: Research on F&B Products at Service Points’, Journal of Trade Science, 9. (Accessed: 17 November 2022).

Hong, S., Kang, J.A., and Hubbard, G.T. (2018) ‘The effects of founder’s storytelling advertising’, International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 22(3), pp.1-9. (Accessed: 30 November 2022).

Illengberger, R. (2022) The Metaverse Paradox: Why the Industry needs Standardization. Available at: https://www. weforum.org (Accessed: 7 November 2022).

Industry News. (2022) ‘Kornit looks to ‘Metaverse’ for ondemand garment printing’, Images Magazine, 7 March. Available at: https://www.images-magazine. com (Accessed: 30 December 2022).

Jin, S.V. and Phua, J. (2015) ‘The moderating effect of computer

users’ autotelic need for touch on brand trust, perceived brand excitement, and brand placement awareness in haptic games and in-game advertising (IGA)’, Computers in Human Behaviour, 43, pp.58-67. (Accessed: 20 November 2022).

Kent, S. (2022) ‘What Europe’s Energy Crisis means for Fashion’, Business of Fashion, 9 Septmeber. (Accessed: 24 December 2022).

Kering. (2022) Our Strategy. Available at: https://www.kering. com/ourstrategy (Accessed: 6 November 2022).

Khan, A. and Beverland, M., (2021) ‘Building a Lifestyle Brand Through Extensions: Bhumi Organic Cotton’, In Fashion Business Cases: A Student Guide to Learning with Case Studies (pp. 118-123). Fairchild Books. (Accessed: 24 December 2022).

Ki, C., Lee, K and Kim, Y.K. (2017) ‘Pleasure and guilt: how do they interplay in luxury consumption?’, European Journal of Marketing. (Accessed: 17 November 2022).

Kim, J.H. (2019) ‘Imperative challenge for luxury brands: Generation Y consumers’ perceptions of luxury fashion brands’-commerce sites’, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management. (Accessed: 17 November 2022).

Lee, A. (2016) ‘Burberry’s Art of the Trench, A Hero Campaign for All’, Harpers Bazaar, 19 April. Available at: https://www. harpersbazaar.my (Accessed: 30 November 2022).

Lee, K., Chung, K.W. and Nam, K.Y., (2013) ‘designable touchpoints for service businesses’, Design management review, 24(3), pp.14-21. (Accessed: 30 November 2022).

Lee, Y.K., (2021) ‘Transformation of the innovative and sustainable supply chain with upcoming real-time fashion systems’, Sustainability, 13(3), p.1081. (Accessed: 30 December 2022).

Lourenço, N., Assunção, F., Maçãs, C. and Machado, P., (2017) ‘EvoFashion: customising fashion through evolution’, In International Conference on

Evolutionary and Biologically Inspired Music and Art (pp. 176189). Springer, Cham. (Accessed: 24 December 2022).

Manlow, V. and Nobbs, K. (2013) ‘Form and function of luxury flagships: An international exploratory study of the meaning of the flagship store for managers and customers’, Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal. (Accessed: 17 November 2022).

Manzano, R., Ferrán, M., Gavilan, D., Avello, M. and Abril, C. (2016) ‘The Influence of Need for Touch in Multichannel Purchasing Behaviour. An approach based on its instrumental and autotelic dimensions and consumer s shopping task’, International Journal of Marketing, Communication and New Media, 4(6). (Accessed: 17 November 2022).

Maslow, A.H. (1943) “A Theory of Human Motivation”, In Psychological Review, 50 (4), 430-437. (Accessed: 6 November 2022).

McKinsey. (2020) Meet Generation Z: Shaping the Future of Shopping. Available at: https:// www.mckinsey.com (Accessed: 6 November 2022).

Mira, N. (2021) ‘Why Dubai is increasingly a magnet for luxury’, Fashion Network, 29 October. Available at: https:// www.uk.fashionnetwork.com (Accessed: 20 November 2022). Moeran, B., (2006) ‘More than just a fashion magazine’, Current sociology, 54(5), pp.725-744. (Accessed: 30 November 2022).

Moore, C.M. and Birtwistle, G., (2005) ‘The nature of parenting advantage in luxury fashion retailing–the case of Gucci group NV’, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management. (Accessed: 30 November 2022).

Moore, C.M., Doherty, A.M. and Doyle, S.A. (2010) ‘Flagship stores as a market entry method: the perspective of luxury fashion retailing’, European journal of marketing, 44(1/2), pp.139-161. (Accessed: 19 November 2022). Mrad, M. (2019) ‘From Karl

Lagerfeld to Erdem: a series of collaborations between designer luxury brands and fast-fashion brands’, Journal of Brand Management, 26, pp. 567-582. (Accessed: 20 November 2022).

Oosthuizen, K., Botha, E., Robertson, J. and Montecchi, M., (2021) ‘Artificial intelligence in retail: The AI-enabled value chain’, Australasian marketing journal, 29(3), pp.264-273. (Accessed: 30 December 2022).

Park, E.J., Kim, E.Y. and Forney, J.C. (2006) ‘A structural model of fashion oriented impulse buying behaviour’, Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal. . (Accessed: 20 November 2022).

Parkes, J. (2021) ‘Balenciaga debuts “raw architecture” store aesthetic at Sloane Street flagship’, Dezeen. 26 October. Available at: https://www.dezeen. com (Accessed: 7 November 2022).

Peck, J and Childers, T. (2003) ‘Individual Differences in Haptic Information Processing: The “Need for Touch” Scale’, Journal of Consumer Research, 30. (Accessed: 15 November 2022).

Peirson-Smith, A. (2019) D&G Go Home Now! Cultural Sensitivities, Local Awareness, and Customer Relations for Luxury Brands Operating Overseas. London: Bloomsbury Academic. (Accessed: 15 November 2022).

Piancatelli, C., Carbonare, P.M.D. and Cuadrado-García, M. (2020) ‘Balenciaga: The Master of Haute Couture’, In The Artification of Luxury Fashion Brands (pp. 141-162). Palgrave Pivot, Cham. (Accessed: 7 November 2022).

Posner, H, Williams, S, & Posner, H 2015, Marketing Fashion, Second edition : Strategy, Branding and Promotion, Laurence King Publishing, London. P9-27. (Accessed: 6 November 2022).

Radón, A., (2012) ‘Luxury brand exclusivity strategiesAn illustration of a cultural collaboration’, Journal of Business Administration Research, 1(1), p.106. (Accessed: 1 December 2022).

Royo-Vela, M., and Sánchez, M.P., (2022) ‘Downward pricebased luxury brand line extension: Effects on premium luxury buyer’s perception and consequences on buying intention and brand loyalty’, European Research on Management and Business Economics, 28(3), p.100198. (Accessed: 1 December 2022). Sabanoglu, T. (2021) Online Personal Luxury Goods Market – Statistics and Facts. Statista. . (Accessed: 17 November 2022). Sacheti, P. (2022) ‘What exactly is a ‘Museum of the Future’, Art news, 25 May. Available at: https://www.artnews.com (Accessed: 20 November 2022). Schroeder, J.E., (2009) ‘The cultural codes of branding’, Marketing theory, 9(1), pp.123126. (Accessed: 1 December 2022).

Seo, Y and Buchanan-Oliver, M. (2014) ‘Luxury Branding: The Industry, Trends, and Future Conceptualisations’, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 27(1), pp. 82-98. (Accessed: 15 November 2022).

Shaikh, A.D., Chaparro, B.S. and Fox, D., (2006) ‘Perception of fonts: Perceived personality traits and uses’ Usability news, 8(1), pp.1-6. (Accessed: 1 December 2022).

Solca, L. (2022) ‘The Secrets to Kering’s Fashion Success’, Business of Fashion, 25 October. Available at: https://www. businessoffashion.com (Accessed: 6 November 2022).

Spena, T.R., Caridà, A., Colurcio, M. and Melia, M. (2012) ‘Store experience and co-creation: the case of temporary shop’, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 40(1), pp.21-40. (Accessed: 19 November 2022).

Stone, M., Bearman, D., Butscher, S.A., Gilbert, D., Crick, P. and Moffett, T., (2003) ‘The effect of retail customer loyalty schemes— Detailed measurement or transforming marketing?’, Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 12(3), pp.305-318. . (Accessed: 20 November 2022).

Vaziri, M., Llonch-Andreu, J. and López-Belbeze, P., (2021) ‘Brand clarity of local and global brands in fast-moving consumer goods: an empirical study in a Middle East country’, Journal of Islamic Marketing. (Accessed: 1 December 2022).

Vempati, S., Malayil, K.T., Sruthi, V. and Sandeep, R. (2020) ‘Enabling hyper-personalisation: Automated ad creative generation and ranking for fashion e-commerce’, In Fashion Recommender Systems (pp. 2548). Springer, Cham. (Accessed: 19 November 2022).

White, J. (2013) ‘Soho Magic’ Workshop Journal 75,(1), pp. 281-286. Oxford University Press. (Accessed: 19 November 2022).

Williams, G. (2022) ‘Four years on, Dolce & Gabbana speaks out after China scandal’, Campaign, 4 April. Available at: https://www. campaignasia.com (Accessed: 15 November 2022).

Xu, M. and Nuangjamnong, C. (2022) ‘Determinant Factors Influence the Purchase Intention through Balenciaga Handbags in the Luxury Product in China’, International Research E-Journal on Business and Economics, 7(1), pp.30-43. (Accessed: 7 November 2022).

YPulse. (2022) Gen Z Is More Interested In These Fashion Trends Than Millennials. Available at: https://www.ypulse. com (Accessed: 24 December 2022).