Open Mic A conversation with Alessandra Rampazzo (AMAA)

Curated by students enrolled in the “Video, Media, and Architecture” class taught by professor Marco Brizzi at Kent State University in Florence in Spring 2022.

Curated by students enrolled in the “Video, Media, and Architecture” class taught by professor Marco Brizzi at Kent State University in Florence in Spring 2022.

Alessandra Rampazzo is a young architect located in Venice, Italy. She graduated from Università Iuav di Venezia (IUAV) in 2010 with a Master’s degree in Architecture and then completed her PhD in History of Architecture in 2017, with her thesis “Steel like Straw” which was about Louis I. Kahn, a famous American architect, and his work in India. Her thesis was published in 2020.

Rampazzo cofounded AMAA in 2012, with her former IUAV classmate, Marcello Galiotto. Prior to starting their own firm, they worked alongside famous architects Massimo Carmassi and Sou Fujimoto. AMAA’s main office is in Venice, Italy, and an additional branch was opened in 2015 in Arzignano, Italy. AMAA works at a variety of scales, from local to global projects both for private commissions and architectural competitions. Since 2010, they have received many awards, such as the Runner Up in the Europan 11 competition (Linz, AT), Third prize at House in the Milano Sesto Competition. More recently as a temporary group (RTP), AMAA won first prize for a residential building for IPES in Bressanone (BZ) and for the RSA extension in Borgo Chiese (TN). In 2020, AMAA’s “Final Outcome” project was awarded first prize in the Young Italian Architect’s competition.

Allison: Okay, so I have the first question. So first of all, thank you so much for coming. We’re all very excited for this opportunity. And the first question I have for you is that AMAA is described as a collaborative office for research and development. So what does the research aspect look like in your office? And how is it represented? And then why have you chosen to represent your research in this way?

So we start with a very difficult question. Summarizing everything just with the one question. So first of all, the name is actually a very funny but complicated story. We are two partners, Alessandra and my partner Marcello [Ed: Galiotto], so it’s actually A and M. We both started studying with the same professor, in Venice, architect Massimo Carmassi. He was also based in Florence for a long time in his career and he’s very into designing with perfect shapes, kind of trying to reference Louis Kahn’s architecture.

And so we started thinking that even if we were two, we were working for more than two, let’s say for four. So then we said: okay, let’s do it like A plus M, but in a squared design so it’s actually A plus M square. The result was very complicated but then we wanted to keep the reference to the formal shape.

The communication of the name was unfortunately getting more complicated and sort of annoying. That is why we started to simplify the name. And in the end, we discussed with a web communication agency that we contacted to restyle our profile. They were the ones suggesting to keep only letters and avoid any symbols or numbers.

The meaning was not at all changed because it’s A plus M but then 2 is two A, so AA, so that’s the name. And actually the story of the names is also important

because it’s also related to the fact that we’ve never been alone and that’s why we added the statement: collaborative research office. We were always two, but then we decided to (as partners) we were never only two. We were always collaborating with other people and with other students. We worked in the University as teaching assistants since the begining, and we were always in contact with the students that were coming to the office to do their internships. As a result we were constantly more than two. I mean, architecture is always working in team. Discussing with other people always improves the project and that’s why we use the expression “the collaborative office and research and development”. Yes, it’s an office that is dealing with designing like projects, but it’s also trying to set up a language that is related to the research that you can do through the project itself.

“We were always more than two. I mean, architecture is always working in a team.”

But also through trips and readings, researh basically. All those aspects, we tried to relate with our profession, put together in the name.

Eleni: Speaking about the research that you do in your firm, how does that differ from what most architectural offices have to offer?

I don’t know if we are different. We’re trying to establish our way of dealing with architecture, but it’s actually something that you’re also taking from others.

For this reason were collaborating with other young practices through competitions and also with projects for private commissions. We are trying to follow our route that is related to what we had learned at university, and what we had the chance to to learn with Massimo Carmassi.

After that, both Marcello and I experienced getting a

“It’s always evolving for sure, because what we did the first year is not the same as what we’re doing today.”

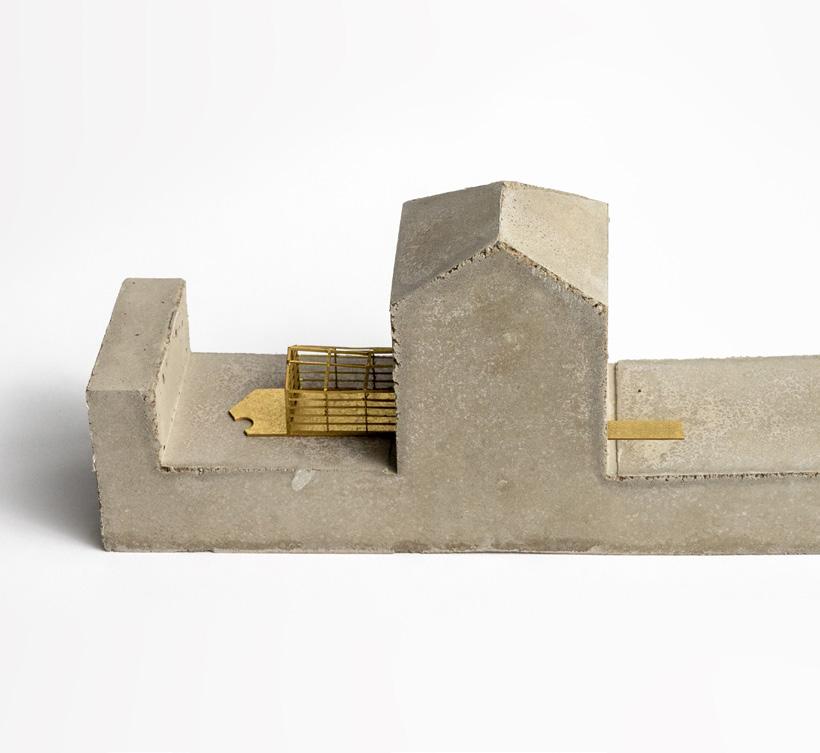

AMAA Final Outcome Model Workshop in Arzignano 2019

Photo by Francesca Vinci

AMAA Final Outcome Model Workshop in Arzignano 2019

Photo by Francesca Vinci

PhD at IUAV in Venice. I got a PhD in the history of architecture. While he was more into the Design field. In the meantime, while I was traveling to India for the research, Marcello went to Japan for one year and he worked for Sou Fujimoto Architects in Tokyo.

We try to follow all those inputs; putting all those inputs together while we try to go on with our language in a way. I mean, it’s always evolving for sure, what we did at the very beginning is not the same as what we’re doing today for sure. But in a way you can kind of recognize a specific manner of dealing with the project, it’s actually the process that’s important. We are following the same kind of approach but expressing the final project in a different way, of course.

Colton: Being such young architects, how do you fit in and work alongside the older architects, with their education and history of the surrounding cities they know how to build and function with what’s given to them, Is this intimidating to you at all? Let’s see. Being young architects sometimes makes the work a little bit more difficult. You have to support yourself and kind of show that you can do it, I mean that you are able to do it, even if you don’t have such a great or long experience in doing it. In other

words, you have to convince the client that you are okay for the assignment. This is something that may give you the possibility of more freedom, and maybe even more in comparison to older architects. You probably want to experiment more and you also have more enthusiasm than the people that are older professionals. They have already arranged to the level that they wanted. So being a young architect can be difficult but it’s also something that you have to take for what it is. It’s okay to deal with older architects, but it also depends on who they are. They can be a reference and they can also be a help because you can even call them and ask for advice.

It was maybe at the beginning difficult but the more you work, the more you can talk at the same level. It’s not that the older architect is, for sure, the more expert they are than you. I mean, maybe you can do something better and so can they, but you can also add something else from a different side.

It’s a source, it’s always a matter of collaborating even with history and architects from the past. Regarding this, I think it’s more or less the same: you can take from the past what you need, as advice and references. This we immediately learned how to do it, as we started working in Venice. We think you cannot avoid confronting

“It’s always a matter of collaboration.”

what already exists. For us and our experience in design, we can say that we can do it better than confronting with a flat void land. When we have a reference within the context (it can be a monument, or it can also be everyday architecture, even a generic place in the countryside that has no specific value) it’s always better for us because we feel to have hints to start the process of the project in this way it is easier for us to get the point of the design. You know, it’s always a matter of adding something to what exists already, and this is something that we feel is more stimulating than having a flat land, where we can do whatever we want.

In a sense, it’s always a matter of collaboration, a collaboration with the context.

Logan W: My question deals with your decisions towards representation and communication of your work. It seems like you are very intentional towards your means of representation, using models dominantly. I was wondering if choosing to only present your work through a platform such as Instagram is also intentional and what kind of benefits or effects that you have seen?

Yeah, it is actually. I mean, everything is. We started in

Space within a Space Model Demonstrates the scale and tension created by the stacking of the 8 shipping containers.

“The use of the model is actually very important for our practice. It’s not something that we use as a little nice product that you can show at the end, but it’s something that is within the broad process of the project.”

a way, and later on when we decided to renovate our image. We understand that not everything needs to be published, and not everything deserves to be shown to the rest of the world, let’s say. And so, of course, the fact that you only see part of our work is perfectly intentional. And the use of the model is actually very important for our practice. It’s not something that we use as a little nice product that we can show at the end, but it’s something that is within the broad process of the project. Even if it seems that it’s nicely prepared and it’s all perfect, it’s actually something that we use to discuss the project in the office. It is also true that we are making different kinds of models. The ones that are shown are mainly the ones that are made in concrete and with golden piece on top, but we are also using study models that are more informal, less precise, and quicker to be done. Also, the selection of the materials used for the model as a reference to our work is really related to what we do as architects at the real scale of the building. The fact that we are using the same kind of concrete that we use in the project is not unintentional. It’s actually coherent with the importance we give to concrete. It has a specific value for us since it is something that you can cast the way you want. It expresses what you were actually thinking for the place. And it can be very perfect but it can also

be very rough. We have a lot of examples for that. I mean, it can be also used for a lot of purposes and in various ways, but in the end, it gives the different feelings to the space.

So since we are using a very limited amount of materials and on the same project, the fact that with one material, you can express a lot of things is reall important to us. There is a possibility to experiment a lot, still within the idea that using less materials is better than adding more.

Tim: I have a follow-up question about physical modeling… you said you use it in your discussion with the office, but then you also portray it digitally so that other people can find and see those physical models. Since you specifically choose not to show all your work online, what is the intention behind showing your physical models to the world?

It’s a sort of language. I mean there are architects that are controlling drawings a lot in order to be shown, like Valerio Olgiati for example, who at the Accademia [Ed. the Accademia di architettura in Mendrisio] is working with the students, asking to use different, specific pens for sections and other parts of drawings. We are also very into controlling (because it’s never

unintentional) even the drawings. This approach is coming from Massimo Carmassi, and his attitude tiward drawing, for whome drawing is very important.

But also, the model is a tool in architecture. It’s very important to use drawings, but of course we’re using models because especially at this first stage it’s abstract enough not to go into too much detail too soon. It’s also very useful with clients because sometimes they don’t perceive the space; they need something to understand how the volumes are. If you immeadiately start modeling digitally, the risk is that you go too far and too fast into details and they start discussing something that is not useful for that moment of the process. There is something more important in the design before those details. The model gives you this kind of abstract approach that shows the volumes and the relationship with the context as well, but not too much detail. And actually on Instagram, the posts are always structured like that.

We have the models and we have some specific drawings that are meaningful for that project. Then we are also adding images of the project , a few renders in order to understand materiality as well. So we are actually using all the tools that are available nowadays. I mean digital is good, but we think that

it’s also useful to remember that we’re coming from traditions, and knowing how to use the basic tools like drawings, models, sketching, perspective gives you the possibility to better use what we have today, which is 3-D modeling and renderings as well.

Gwen: What has been the most difficult part of owning an architecture firm thus far? What advice do you have for architecture students who want to start their own firm after graduation?

So, nothing is actually easy in life but I mean, architecture is not just a job. It’s a passion first. So whenever you feel passionate, you can actually face everything even though it’s not easy. I mean, if you don’t have any real connection with this world already, it’s even harder.

When we started the firm, we had some connections. At the beginning, we graduated and then we started as a firm that was only doing competitions; we decided to take like two years to experience competitions in order to sortof create some publicity. We started like that: let’s say that it was more a theoretical approach because the competitions you can participate in at the beginning are always complete idea competitions. So they’re never going on after you’ve won or after it’s finished

“...Architecture is not just a job. It’s a passion first. So whenever you feel passionate, you can actually face everything even though it’s not easy.”

but it gives you the sort of experience in designing that Marcello and I have. We had some other people that we were discussing the competitions with but we were the only ones working on the projects, and we were doing like three or four competitions a month so that was a lot of work. Basically 24 hours of architecture. So that’s why I’m saying that if you don’t feel the passion it is even harder. I mean, because then you cannot accept that you are physically working so long on the same kind of project or field. After these two years, my dad, who owns a construction firm in Venice, gave us our first client. It was a huge help. I mean, we don’t have to hide under a finger because it’s always like that: having proper connections makes life and things easier. But then you have to keep going because with the first client you have to prove that you can manage what they’re asking for and then you have to keep pushing towards your bigger goals. We also decided to always keep both sides of the profession.

One side is the private commissions, and the other is competitions because otherwise, you’re kind of limiting your possibilities because private commissions are okay but then, even if you’re very lucky and you have a private commission for a big building or very important building, you are still often limited to the private sphere the owner. In other

words you cannot really show yourself and your work to the public. While with a competition, if you have the chance to win and then if it goes on till the final construction then you have a public building that holds your name as a designer.

Eleanor: How did you go from studying and working in education to transitioning into owning and practicing with a firm? What were some of those necessary skills you found you needed to develop to be successful in the professional world, that you might not have seen in the education world? Hmm. It depends on the university actually. For example at IUAV, the School of Architecture of the University of Venice, you always have to build up your own personal way of doing stuff. This is very useful for the next steps in the professional life. In a smaller universitymay be smaller, so students have a more direct relationship with their professors and, consequently, find more support. Coming out of such a school, you will feel a big difference when you start your own practice and you are more into the working environment. IUAV was actually a great school in this sense since you are left basically alone in the process of building up your own future.

Marco: How many students are in the classes? Just to give an example.

At least 60 to 70 in the design courses. The history of architecture classes might have more than a hundred students enrolled. This is why I’m saying that you are kind of alone… numbers make a difference. Talking about profession, you have to sort of adapt to the client and be open to discuss and to be discussed, also. Sometimes you’re suggesting stuff are not really appreciated, but you feel the need to ustify your choices same as you would have done infront of a professor at the university.

Allison: I wanted to ask you because you’ve been working with Marcello for so long: what advice do you have for working in a partnership?

Not easy at all. It was a great opportunity since the begining because we can discuss on the project which is always better than being alone. Once feel the pain for working on the project you cannot really take a step aside and be a critic on what you did. That’s why it’s always important to discuss with someone else. Being more than one is always more difficult, but of course, me and Marcello are kind of used to work together because we started this collaboration from the second year at the University more than

10 years ago. Right now, we are not really working together like it was at the beginning since we have two different offices.

One is in Venice where I am, the other is near Vicenza. We have different projects, but of course, I trust what he does and he, does also because we have already set a sort of a guideline to follow. The beginning, was more about continously sharing opinion. What is interesting is that we have never been overlapping each other. We have different skills. In selecting partners it’s important to avoid the possible overlapping: then you can always think to add something without erasing something that he did or I did. It is important to keep a criticalapproach bu with the idea of always adding something new solutions or alternatives.

Logan A: I’d like to transition the conversation a little bit to some of the ongoing thoughts and ideas from your practice. I’ve noticed that your approach doesn’t restrict the design to being finalized through drawings and models, but you will allow the project to evolve during the construction process. So considering the economic systems in which we operate today as designers, how do you overcome some of these restraints or pragmatic limitations

to extend the construction phase as a continuation of the design process?

Actually, the site is always a great problem. I mean we think that the project is never and really finished especially if you’re dealing with existence (the process of restoring and adopting or reusing existing buildings). The site is part of the process and part of the design itself. There is a lot of things that you cannot really predict from the beginning, its’s impossible even if you are very precise. There’s always something that happens that you cannot control, and that’s why the project itself needs to be more of a guide or like a bigger idea that you have that you can follow even if the circumstances change during construction. This is a little bit different when you’re dealing with public projects, and also it’s less like that when you’re dealing with something that is completely new. I mean, if the project is completely new, then you have to predict everything because you’re not supposed to change anything on site. Also with public projects it’s a little different because there the budget is fixed and it’s always difficult to increase it. But still, if you’re facing existence then you have to cinsuder the necessity of keeping woring on the project during the site. That is something that could be really interesting.

Logan A: You’ve mentioned that you’re interested in the notion of the unfinished, and particularly allowing the process to evolve during construction. So, do you ever think that the notion of the unfinished can extend beyond construction into occupancy, or do you ever anticipate unexpected adaptations from the users of the space?

It depends on the use of the building. I mean, we did a lot of residences and we tried to design almost everything inside the house, especially the fixed furniture. This, because we think that it’s not something that is separate from the space, but it is actually something that makes space as well. But it’s also true that you have to accept the change that the occupants can do inside their home. This may be difficult for us as architects. There was a very interesting thought on that at the Swiss pavilion [Ed. at one of the past International Architecture exhibitions of La Biennale di Venezia]: they were documenting the fact that architects are taking pictures of their projects, when they are completely empty, not accepting people or anything not decided by the architect itself. It’s also true that we may have to start to also accepting the fact that the use is important for people that you are designing for. This is something that we

took from the Japanese lesson, since Sou Fujimoto was very focused on the idea that the design is for people. Avoiding everything coming from the people and within the space is then impossible. Yeah, architecture is not finished until whenever.

Dominic: I’m curious on how you value the relationship between permanence and impermanence or rather rigidity and flexibility?

As Italians we have the idea that the architecture (buildings) should remain. This isn’t everyone’s view. Coming from different parts of the world, it’s not obvious at all. The experience in Japan gives us the idea that this concept we have is not obvious at all. People are changing without any attention or without feeling the need of preserving what they have. As Italian architects we tend to keep almost everything, even too much sometimes. The use of the materials is related to this idea of permanency and this way of seeing architecture, for sure. Concrete is more permanent than wood. They have different levels of permanency and that’s why the material is also related to what it’s expressing within the buildings. Concrete or steel are used for structures which need to be more permanent. Then you have all the other materials that can be added, dismounted, and then changed.

Eleni: As architecture students, we have had architectural history classes, studied precedents, and students may have many opinions about how we disagree with decisions on projects. Were there any specific moments in your architectural education where you felt a strong urgency or inspiration to make a change in the architecture industry? And if so, how do you plan to work towards that?

This is something that we are discussing, maybe more now where it looks that Italy doesn’t really have a younger generation of architects. If you look at the newspaper or in the bigger press, you don’t feel this presence. What if we look next to each other next to the other architects we are collaborating with we seeing a lot of young people doing stuff, feeling exactly the opposite, not only us but a lot of other younger practices are now expressing their languages and they’re doing it pretty well. This is not appearing to the world, but it is something that we’re questioning a lot. This (interview) is something that we can be proud of, I’m here, so, thanks for that because it’s also an opportunity. It’s something that still helps young generations to be shown maybe not to the world but to a bigger crowd, for sure. This is the bigger urgency that we feel:

how to show ourselves to the world, as a category of younger architects. If you’re looking carefully, you see a lot of practices that are not only being louder or have bigger projects that keep them going economically speaking, but they’re also trying to express a specific research. This is something that we are also trying to do.

Andrew: My question is pretty similar, being that I was curious, with you being from a different part of the world than us, what do you see in Europe, or Italy specifically, are some of the biggest issues within architecture today? Would you say politics, or economic issues like we have back home, or if you think it’s more issues dealing with young designers being underpaid or overworked? Or if it’s a totally different dynamic here, with what you’re saying, which is to imply there aren’t as many young designers here, I’m curious what you think?

No, it’s actually that there are a lot of young designers, it’s just that they are not really sponsored by the bigger press...

And that is maybe because here, in a way, we are always relating to traditions, same for buildings and same for practice. That’s why we feel the urgency to kind

of find a way to show our world. And, also, this is why we always thought that it’s important to collaborate with other offices, with different offices, it is not easy at all, and it’s actually very rare. But we always had this approach, I mean, we always wanted to share. We are open to share whatever you need and whatever we’re asking for: we’re not really hiding anything. I mean, if you ask to come to the office, you can come and see whatever we are doing. This “generous” attitude is not that obvious and this is what might lack today among younger practices. As I said at the beginning, this would make stuff easier. So, we have to keep fighting...

Dominic: I’m curious about the process that you go through. You talk a little bit about how the site is sometimes like the most difficult portion that you deal with. Do you face other obstacles such as social context or program that might be just as difficult?

I mean yes. The inputs for the project are a lot. There can be limits, but also within the limits you can have occasions. For example, rules seem annoying at the beginning, but then within the rules, you have to find your way to express something that goes beyond those limits. This is what we always try to do. Not just

“This is something that we can discuss right now and maybe this is the bigger urgency that we feel: how to show ourselves to the world.”

reading the rules, and then being flat, but trying to evolve the design in order to go beyond what is visual. Nobody is inventing anything, at least now. So it’s always a process that comes from the concept phase, goes to the design, and then the construction as we said before. But it’s never linear. It’s not always like a theory to order, and then the final outcome, it’s always a mix of that. When you think that you are okay with the design, you start having doubts and then you go back to theory and the concept as well.

So if you’re making a restoration, you go into the site and you still have doubts and so you go back to the theory. So, its not even a circle. Just a very confusing process that has those three moments that are always mixing.

Justin : You talked about the collaborative ability for two to share information between each other. You also referenced both Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn, who worked extensively with each other, almost as a master and apprentice. Considering that the globalization of information allows learning to be accessible to almost everyone, where do you see the relationship between master and apprentice going in today’s context?

It’s the relation with history and what happens— what happened before you arrived at the building, or it’s the thing we were saying before regarding older architects. You are studying the masters in order to get something that is useful for the project, for your language, in order to express your ideas. So every study you do can help you to get what you need. It’s a sort of silent collaboration, because of course, masters are not here anymore.

Marco: You can get information about many master architects very easily today. Access to information is easier than in the past. However, there are fewer masters that you can meet in person. Yes of course, you have more information as well. It actually makes everything easier, but at the same time it depends on what you read and how you read. You can have access to a lot of information, but

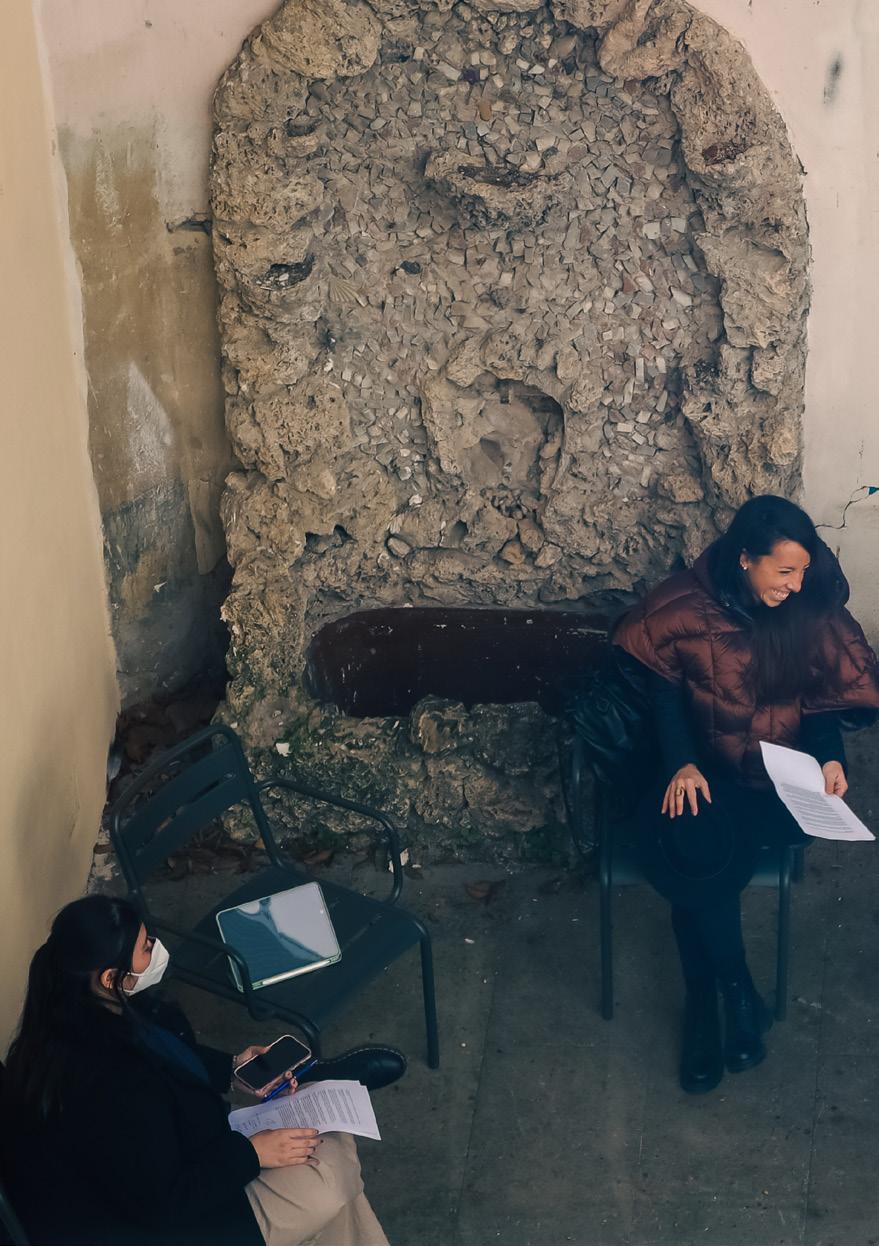

Pleonastic is Fantastic Model Study of tension between old and new created by the stairway.

Photos by Francesca Vinci

you have also to learn how to process it and select the one you want for your practices.

Sometimes you have the feeling that everything has already been said about a specific project. Then you realize that it’s not true, and there’s always something that you can go deeper and deeper on.

Marco: Your experience with Louis Kahn is a clear example.

My PhD Thesis is actually about this. Of course, everybody in the world knew that he had done the Indian Institute of Management, but nobody was

“Sometimes you have the feeling that everything has already been said about a specific project. Then you realize that it’s not true, and there’s always something that you can go deeper and deeper on..”

actually there to see the buildings. If you go there you can see it, you can touch the bricks and finally you can study how they built up that complex. It made all the difference seeing the same building that was only explored before through images and texts. That means that there’s always something to discover.

Katelyn: I find the concept of pleonasm in architecture just really fascinating, particularly in regards to the Pleonastic is Fantastic Restoration that you guys did. So I was wondering if you could elaborate a little

bit about how you would define pleonastic architecture and sort of the value that you think that type of thing and those types of objects bring to the space. Yes, so actually the title was given to the project after we had a lecture on the web during the pandemic period. We had this talk through Casabella laboratorio. During the description of the staircase Francesco Dal Co questioned the real need of the diagonal support below it. The staircase is not touching anything, and in structural terms, it needed that support, but Dal Co was the one saying it was pleonastic. We took that as an idea for the title. Pleonastic is actually fantastic. The title was actually a joke for that project but it shows that even one single element can make a difference in the space. For us, it’s not pleonastic at all, it’s minimal. We didn’t want to be pleonastic at all; we wanted to be essential but iconic. We think that with specific elements you can make a huge difference in the space.

Marco: It’s not a methodology, but a neuronic answer to a question. [Laughing] Yes, sometimes. It’s not, you can see. Sometimes it happens that everything comes at the end of the process.

Katelyn: In an essay on ceramics and architecture Sou Fujimoto says, “I prefer something like the cave-like-unintentional space. Something that is in between nature and artifact—formless form.” And I know this quote has been brought up in the context of the Space within a Space installation, so I was wondering if you could talk about how this idea influenced the project and any influence he has had on your architectural outlook in general. So the reference to the cave is exactly coming from Sou Fujimoto: he’s talking about the nest and cave, and he focuses attention to the fact that you’re designing for people. So, you have to be careful on what you do, with the space, because the space needs to be prepared for someone. And so we had this space —and I’m referring to the Space within a Space installation — this free space next to the office, actually in the same building, and we tried to prepare the space using elements in the same way we did with the staircase project. So few elements that can be put together in order to completely change the spatial perception of the same space without erasing the bigger space itself. So you keep the building, the envelope, and then you’re completely changing also the proportions that you can feel inside of it.

In order to do that, we had this idea of recycling trucks, containers, and assembled them in order to get this idea of a complex space that you can go through. It’s an exercise. How can you change the perception of space with very limited things. You don’t need to do a lot in order to change the feelings within the space

Ramzey: I had a question regarding interiors. Of course, the most effective method of understanding and experiencing a space is by physically occupying it. Because this yet isn’t possible while designing, the next best option is to simulate the experience. In your design process, you express a desire to “... limit the use of perspective representations (renderings),which are very much in vogue today, which mimic a reality that is often inconsistent with the project”. Do you believe physical models are the best way to communicate interior spaces? Or do you feel more recent advancements including project animations, walkthroughs, and virtual reality can be used to better simulate the interior of a project? The tools that you use is related to the project, I think. And also the scale because we are always showing models

that are at a 1:500 scale more or less. For example, the ones with concrete bases and small objects on top. But we also do bigger models, like at 1:50 scale. With those models you go into more details of the interior space. Even 1:20 and bigger and bigger if we want to investigate something that is more detailed and related to the interior. So the same tools can be also used in a different phase of the process. But of course, when you’re talking with clients and also for your research on the project, it’s necessary to use other tools as well. I mean, digital modeling is impossible to avoid because it gives you the possibility to have the final image of the project itself where the materiality comes to life, which is also important for us.

We are choosing specific materials so you have to control them from the beginning. Having the possibility to use visuals or animations is very important. Especially if you want to communicate it to the client. We as architects have a lot of imagination and we can see things that are not really drawn. The clients don’t have the same skill as us and this is very important to know because we have to communicate and convince them. The more you show, the more they can feel the finished product.

This interview with Alessandra Rampazzo was focused upon the creation and management of a young architecture firm, intentionallity behind representations, and the challenges young architects face in the field today. It was a collaborative effort among students of the Video, Media, and Architecture course at Kent State University Florence. Guest lecturers were brought in from all over Europe for a Spring lecture series and students were tasked to create an interview before each of these lectures. After analyzing numerous interviews with other architects, students researched and explored the work of the visiting lecturers. Questions were then devised by each student, and these questions were analyzed based upon their thematic similarity and their relevance to the work of each lecturer. The most appropriate questions were chosen for each interview, and the specific students who created these questions then were charged with interviewing our guests, using the chosen questions as a base and posing any other questions that flowed with the interview.