Towards the Future of Research Education in Architecture based on the international symposium held

at KTH in Dec. 2023

at KTH in Dec. 2023

of

Education in Architecture based on the international symposium held at KTH in December 2023

School of Architecture KTH

Printed in Stockholm 2025

10

63 78 86 94 104

Perspectives

Chalmers Gothenburg

KTH Stockholm

LTH Lund

UMA Umeå

AHO Oslo

EKA — Estonian Academy of Arts

KADK — Royal Danish Academy

KU Leuven

TU Delft

UCL The Bartlett

Doctoral programmes — facts and figures

ResArc — a brief history and future possibilities

The funding landscape for PhD positions in Sweden

Final notes — challenges and potentials

Appendix

What are the main challenges that architectural researchers need to address in the near future? What approaches, knowledges, and skills thus need to be ensured and passed on through research education? From a backdrop of the pressing concerns that dominate the present moment — rapid technological transformations, increasing socioeconomic divides, vast concentrations of power, escalating levels of war and violence, and where the effects of climate change have become ubiquitous — these issues sat at the core of a two-day symposium, held at the School of Architecture KTH in December 2023.

Organised around three interwoven themes — topics and challenges; methods, skills, and knowledges; and the significance of research for practice and society at large — the symposium gathered an international array of researchers, educators, scholars, and stakeholders in close-knitted round-table conversations. A common premise for these discussions was that architectural research today is a multi-modal, explorative, and heterogenous field — verging from critical historiography and the humanities to critical urban cartographies and digital fabrication — defined by cross-, inter-, and transdisciplinary exchange.

The symposium made it clear that research

education is not only about fostering academic skills, but encompasses a larger sphere of knowledges, tools, and practices related to the built environment, as informed by a strong ethical agenda. Discussions were held on the role of architectural research in shaping public discourse and policy, on expanding on the forms of dissemination, and on its potential to influence how societies respond to climate change, urbanization, and social inequities. In particular, there was a strong call for research that actively engages with marginalized communities, recognizing their voices as essential to the creation of just and resilient built environments. The importance of fostering a research culture that is both rigorous and responsive to real-world challenges thus emerged as a central concern.

Offering a critical space for dialogue and reflection, the symposium was an initiative of the Swedish national school of research education in architecture ResArc (https://resarc.se ). Drawing on its agenda and our collective experience of providing doctoral courses to PhD candidates for now over a decade, the symposium was integral to the process of assessing these years and in making preparations for those to come. With this publication, Towards the Future of Research Education in Architecture , we wish to make some of the insights that emerged through the symposium more accessible to a larger group of stakeholders. Placing the emphasis on the voices and perspectives of those

actively involved in research education — rather than on policies, charters, and other steering documents — the contributors to this publication are all researchers and educators, situated at the four architectural schools in Sweden and in six other European countries. Forming part of the institutional network that ResArc has developed over the years, the international contributors provide an important context for our assessment of the challenges and potentials of conducting research education in Sweden. To further that end, in this publication we are providing additional information as regards to the varying conditions of educating researchers as defined by national and institutional regulations. Special emphasis is placed on the funding of doctoral students in Sweden together with an account of ResArc’s history, which has not previously been documented.

Less a record of the symposium, and more a forward-looking guide as regards to the potential of research education, with this publication we are addressing all those who share our commitment in safeguarding and advancing research in architecture, and who recognize the significance it holds for making, interpreting, and shaping the built and lived environment. While we do not claim to provide an overview of this field, nor a complete survey of the different conditions for conducting PhD education across Europe, we are confident that the voices, perspectives, and facts compiled in this publication

are sufficient to capture some crucial matters of concern. The issues raised in this book are not just theoretical; they have practical implications for how we train future researchers, for how research may inform policies and practices, and for how it can contribute to global conversations on sustainability, equity, and social justice. Therefore, this publication also serves as a call for action, for stakeholders both within and beyond academia, in order to ensure the stability and long-term continuity of architectural research in Sweden.

Catharina Gabrielsson, Gunnar Sandin & Isabelle Doucet. Colleagues in ResArc

Catharina Gabrielsson is Professor in Urban design and Urban theory, and director of the doctoral programme at the School of Architecture KTH since 2022.

Gunnar Sandin is Professor in Theoretical and applied aesthetics, and former director of research studies at the Department of Architecture and Built Environment LTH.

Isabelle Doucet has been Professor in Architectural theory and history at Chalmers University of Technology (2018–2025), and is currently Professor with a focus on the architectural humanities at the University of Sheffield (UK).

This section is a compilation of ten perspectives from educators and researchers engaged with doctoral education at schools of architecture in Sweden and abroad. Drawing on the symposium, contributors were asked to consider four topics based on their own insights and experiences. Questions could be responded to freely, and we encouraged a personal note. The topics and questions are as follows:

What makes research in architecture socially relevant? What makes it different or uniquely wellplaced for addressing certain (societal) questions? Which strands, traditions, or emerging practices do you see as particularly important, and why?

What importance (if any) do disciplines have in a cross-, inter-, and transdisciplinary age? What are the benefits, and the potential drawbacks, of educating PhD students from mixed vs. similar backgrounds?

What knowledges, competences, and skills are the most important ones to pass on to young researchers? What are the most important factors of a “thriving” doctoral programme? Any aspects

that are overlooked and should receive more attention and care?

What are the greater benefits (professional or personal) of pursuing doctoral studies and gaining a doctoral degree? What are the potential drawbacks?

Chalmers University of Technology, Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering

ADoctoral studies in architecture — and research in architecture, more broadly speaking — cover a broad range of approaches including theory and history, artistic research, building technology, digital design, and more. While all of these can have societal and environmental relevance, some studies, more so than others, explicitly seek out critical perspectives and transformative action. I am feeling encouraged by how many doctoral candidates I meet who adopt such perspectives. Their historical and theoretical studies — the vantage point from which I, too speak here — expand and challenge dominant perspectives on architectural knowledge, e.g., by diversifying the canon, by expanding and uncovering overlooked (hi)stories, and by carefully listening to previously underrepresented voices.

I am reminded of Rebecca Solnit’s book Hope in the Dark , where she recalls histories of transformative practices whose impact was often only felt over longer periods of time, even beyond one’s own lifetime. Such stories bring hope in that no matter how small today’s actions may seem, they can instil change in the future: “though hope

is about the future, grounds for hope lie in the records and recollections of the past.”1 I often feel that doctoral studies could be considered as part of such important, and generous, commitment. From here I jump to the question of the future.

DResearch in architecture theory and history can bring to the forefront histories previously deemed inconsequential or unworthy of mention; it can trigger action and change and stir up the status quo. In an academic (and funding) climate that increasingly pushes for fast research, high-paced outputs, and demonstrable applicability, critical researchers may struggle to convince others of the immediate (societal) relevance of their work. Frustrating as this may be, it could be taken as an invitation to diversify ways of working, e.g. at different speeds and scales, and to diversify outputs. I think for example of how the Australia-based research project and web platform Parlour: Gender, Equity, Architecture , cleverly combines qualitative feminist research with quantitative data analysis, and provides an online platform offering a wide range of formats: research articles, interviews, personal stories, debates, survey results, opinion pieces, and more.2 While contributing to long-term change and taking the time for difficult discussions, also immediate action is taken. In Sweden, the strong, and sometimes sole, reliance on external funding for appointing PhD

students (and for funding research more generally) poses challenges for developing critical (and longterm) research agendas.

I see an important opportunity for theory, history, and artistic research in architecture in the rethinking of the agency of architecture and the built environment in connection to environmental questions. To this effect, exciting research and doctoral studies can be found at the intersections of architectural studies and the environmental humanities. This brings me to the question of disciplinarity.

BArchitectural studies borrow methods from other fields, including ethnography, feminist historiography, art history, science studies, and philosophy. I am particularly excited to see how a situated, embodied, and relational approach to knowledge production, as proposed by Donna J. Haraway, Anna L. Tsing, and many others, is inspiring doctoral students in architecture. Such approaches prompt us to think the world through connections, placing ourselves, as researchers, firmly within those networks of connections, and not outside of it.

Doctoral students are thus challenged to carefully listen to the worlds they study and co-inhabit, to become curious and attentive to the many connections at work (as Tsing argues)3 all along while thinking through their own positionality,

their own agency in those worlds. Such unpacking of architectural concerns, and to “stay with the trouble,” as Haraway invites us to do,4 is important but challenging work. It unsettles assumptions around suitable source material, which archival traces to follow, which voices to forefront, and how to write such entangled accounts. It also may lead one to decentralise architecture, and the architect, in favour of other agencies.5 It will also, unavoidably, lead to questions of decolonising. That many doctoral students are today willing to take this on, I find very inspiring. But it is sensitive, vulnerable work, and this brings me to the final point, related to doctoral education.

CWhen we want to “stay with the trouble”, we must learn to approach critical questions in inclusive and ethical ways, and with integrity and curiosity. It means that we must learn to listen well, and to also develop ways of writing “with” rather than writing merely “about”. All this takes time, practice, and courage. I feel therefore that while doctoral training should be concerned, of course, with subject-specific content, methods, ethics, and writing, it also should commit to the creation of safe environments where doctoral students feel comfortable to wrestle with partial knowledge, sensitive questions, and with writing “with”. This means to carefully craft pedagogical formats that encourage

collaborative learning through critical engagement, vulnerability, and integrity. In a recent doctoral course that I created within the ResArc network, invited scholars commented on the students’ texts, and the course participants also provided feedback on each other’s.6 Instead of just commenting and focusing on content, participants were tasked to become attentive to how they write comments.

Taking on the role of editor/reviewer, one could more explicitly practise how to write critical feedback constructively and in ways that open for, rather than close, critical consideration and discussion. This dialogic space allowed for sharing the struggles with researching and writing through solidarity and generosity.

1 Rebecca Solnit, Hope in the Dark. Untold Histories. Wild Possibilities Canongate, (2016 [2004]), p. xvii.

2 https://parlour.org.au

3 E.g., Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015)

4 Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016)

5 I experienced this in my studies of multispecies encounters in architecture e.g., Isabelle Doucet, “Interspecies Encounters: Design (Hi)stories, Practices of Care, and

Challenges” in: Environmental Histories of Architecture, ed. Kim Förster (Canadian Centre for Architecture, 2022)

6 Situating Research: Approaches, Ethics, Collaborations, Writing course, 2022–2023, held within ResArc, at Chalmers University of Technology.

AThe social relevance of architectural research plays out both within and beyond the discipline. Whether approached in terms of methods and skills, a form of knowledge maintained through discourse, or simply taken as a synonym for buildings endowed with certain qualities — architecture entails crucial issues to do with spatial processes of production and use along with their intrinsic values. Used as a conceptual lens, it contributes to the building-up of knowledge in the social sciences and humanities; fields that similarly tend to be overlooked in research policies targeting sustainability.

Unlike many other disciplines, however, architecture is firmly anchored in a projective and propositional mode that, to a considerable extent, remains centred on an ethos of bettering lives. It’s a propensity that frequently teams up with — indeed, is indistinguishable from — notions of progress, economic growth, and technological advancement that increasingly are identified as causes for the current crises. Yet, through a close engagement with research, architecture holds the potential to advance more relevant and carefully tuned proposals that take on the challenges societies today are facing everywhere. Architectural research is

vital for supporting the development of practice, for expanding on the scope of what architecture is and does, and for identifying the epistemological blind spots in how spaces are built, organised, used, and controlled. Thereby, it’s part of a much larger movement that counter-acts the “ecology of bad ideas” (as Gregory Bateson once called it) that propagates in the system and destroys the conditions for human and non-human lives alike.

Historically, a number of difficult questions to do with architecture’s contingency with its “background conditions of possibility” (to paraphrase Nancy Fraser) have been suppressed into the disciplinary subconscious. Seen as a coping strategy , this suppression is not unique; all disciplines are based on tacit assumptions that, to a certain extent, are prerequisites for the production of knowledge. But this means that critical insights on how architecture may function as an instrument of power and control, for instance, have primarily originated from outside the discipline, e.g. from philosophy, critical theory, and history.

Feminist architectural theorists and scholars, in particular, have been of crucial importance for bringing such insights into the discipline, reshaping the way architecture is perceived, and expanding on the limits of interrogation. Cross- and interdisciplinary exchange is thus central for archi -

tectural research. But it’s equally important that doctoral students get a sense of the particularities (histories and counter-histories) of their own discipline. The question of disciplinarity thus ultimately concerns the ability to question the seemingly natural laws and boundaries that are installed through education (or disciplination, to speak with Foucault). But it also concerns the ability to see yourself from the outside; to discover and strengthen your own expertise in ways that allow you to contribute with people, thoughts, and ideas from other fields of expertise.

CThe forward-looking, projective, and propositional mode that characterises architecture — both in relation to other academic fields, and to other forms of aesthetic practice — is often also carried over to research. Lenin’s question, “What is to be done?”, resonates in architectural research, no matter how far removed it may seem from practice, and distinguishes it from, say, art history. I like to think of it as an acute awareness of the fact that something is at stake in knowledge production, and in what we do as researchers. It matters how problems are chosen and formulated; in what is taken as sources and collected as data; in how methodologies are devised, and in how we frame, narrate, and compose our findings.

In advancing new perspectives on that which has been ignored, denied, hidden, or overlooked, research (at best) carries an impetus for change. Training the sensibility that creates such an awareness is one of the most important aspects of research education. I see it as an institutional space that should be loaded with tools, materials, ideas, and sources that students both must learn from and explore through peer-to-peer exchange. It constitutes a workshop — a place where “things” are made — but like any workshop, for activities to be meaningful, they must have a direction and an intent.

DSomeone has suggested that academic training, to a great extent, is about the ability to offer and accept critique. Despite the intense focus on individual achievements and the hard-wired competitive system that defines academic careers, research is essentially a collective form of knowledge production that comes with an ethics of respect and care. This is transmitted in everything from selecting sources and working with quotations to techniques of writing and presenting one’s findings in a fair, equitable, and just way.

Installing such virtues in future academics, pompous as it sounds, is not only upholding the principles of science but also of democracy. Along with receiving an education that broadly sets out the framework of what has taken us thus far; learn -

ing to question and to negotiate, gaining confidence and trust in others’ as well as in your own capacities — I like to think that doctoral students are of benefit to society in whatever future path they take. Insisting on academia as an (as yet and in principle) free space is also to acknowledge the fragility of that space. It depends on a shared commitment, and it needs to be porous to the outside; allowing “things” — people, matter, insights, and ideas — to seep through in both directions.

Catharina Gabrielsson, Professor and Head of research education

Lund University LTH, Department of Architecture and the Built Environment

It should be quite clear that current urgencies related to climate and warfare disasters have everything to do with what has to be built, re-built, and altered in the world. To create possible worlds for those escaping from, or staying with, the factual current and future circumstances of precarious life, we need not only to innovate design but also architectural knowledge refined through a long history of previous challenges. The recently awakened intentions to make living conditions for not only humans but also for the species we interact with is also likely to be a growing area for architectural research in the future.

In recent decades, our views on social resilience — or what is regularly traded as “sustainability” — there is a tendency to think in terms of societies or communities. This choice of “target” is, of course, only natural, but even if social conditions are of an overarching concern, it is, on an everyday basis, experienced by individuals. Still, individual existence in the sense of existential perspectives tied to belief, capability, and consciousness are facets that have not yet been recognized sufficiently in architectural research. There is a need to include such perspectives more accurately in the future, not least because when they are not considered, they may brutally

threaten all other traditional community-based societal conceptions, known as “democracy, “agreement”, or “decency”. There is a need for reconsidering the ethics of architecture, not only as a set of rules for how to trade architectural projects, or ideas of what serves nations or communities best, but as grounded in closely felt world views. Research education in architecture can be one of the means needed to formulate from the ground up what such “existential resilience” could mean.

When PhD students from different schools or different subject areas come together, or when they are supervised from more than one discipline, they start the process of internalising a multitude of views and incorporating them into their personal projects. Although it constitutes a necessity for all true processes of knowledge development, interdisciplinary research can be an overwhelming task, balanced only by maintaining attention to certain recurring architectural values — such as the impact of spatiality, materiality and the human relation to these. Such values are hence likely to be cornerstones also in future programmes.

These very palpable and tangible facets, or values, are furthermore what many other disciplines lack or ignore in their perspectives and analyses of “space” and it is a challenge for architectural research, sifting down also to the pedagogical parts of research education, to make others more aware of these values.

The gaining of a doctoral degree is of course not a value per se , even if current CV-oriented paradigms play their role in the affairs of employment, etc. To be able to feel the backbone of knowledge in whatever you start working with after the four (or so) years of contextualised project-centred PhD studies, becomes the ground for your future consultation capacity, depth of design competence, and build-up of new research environments.

Dr. Gunnar Sandin, Professor in Applied aesthetics and Chair of ResArc programme committee 2012–2024

AWhat is needed today is a new beginning, making the world more resilient while recovering and expanding its democracy. It concerns a future change of both the human and more-than-human habitat, one that recognizes the dangers of the pluri-crises we are confronted with, turning towards new horizons of possibility by addressing the impact of global warming, migration, war, inequality, identity, colonialism, nationalism, energy, technology, materiality, and digitalization. To overcome the pluricrises, we need to change our relationship with the physical and spatial world. This necessitates that architecture, urban design, landscape architecture, and their cultural technologies reinvent themselves. Only then we will be able to develop livable futures that constitute a good life for all.

To perceive and experience what new opportunities are possible in the current and future conjuncture — opting for a strategy based on global concern while acting locally — architectural research is of utmost relevance. It enables society to imagine how such a livable civil society could become a reality. After all, architecture remains one of the only spatial and visual expressions in everyday life, allowing us all to experience those projected other worlds and their distinct forms

of organization and value, while simultaneously its architecture projections enable us to imagine another future that architecture’s particular techniques of realization allow.

Architects, more than any other educated group in society, must engage with both economics and biology, human collectives and geometry, history and matter, energy and desire, nature and artifice, technology and automation, care and pleasure, aesthetics and politics. From this perspective, architecture at its core can only be understood as relational and interdependent, operating across many different fields. Consequently, its research must inherently be cross-disciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary.

For a long time, transdisciplinary research analysed the complex realities that architecture is part of without developing alternative routes for how architecture could have a positive impact. While learning from the humanities and the social sciences heavily steered architectural research, empowering a much-needed critical analysis of architecture, its research often foreclosed how architecture could contribute to change; how through architecture’s own zone of competences; the one of spatial, urban, and landscape planning; infrastructure, construction, typology, tectonics, surface and volume, texture, light, material, colour and place

emancipatory influence can be exerted through its performative design.

Now that we are living a rather alarming moment, even transdisciplinary research cannot continue to focus solely on critically examining the architectural consequences of the state of things. What must be taken into consideration is under what conditions, and with respect to what forces, architecture could become active and creative, rather than reactive or nihilistic in confronting the multi-crises of the world today. Such an architecture of polity is as much about thinking and practicing architecture, as cutting a path in the linear flow of history opening the way for some new yet unimagined possibilities, as it is about the discovery, and invention of new forms. Feeling lost and paralyzed, while celebrating the many crises in ever more beautiful prose, is no longer an option. Future research should explore how renewed ideas of societal value and architectural expression (form) can reconnect, daring to create spaces for lives of sustained optimal well-being and joy.

CThe PhD programme at UMA aims to educate architectural scholars who are not only deeply knowledgeable in their specific areas of research but also adept at navigating the complex intersections of architecture, urbanism, landscape, and technology from theoretical, historical, and practical perspec -

tives within diverse cultural, social, and political contexts. Its research is oriented toward the training of scholars in the study of architecture and urban design through technical, historical, theoretical, and natural scientific research and practice, as well as through a more artistic research approach that focuses on the critical analysis of the non-verbal artifacts of architecture beyond the written word. This is achieved by deploying different techniques of visualization and modeling. The programme specifically focuses on generating new knowledge that contributes to human and more-than-human interactions and experiences, as well as embracing the transdisciplinary nature of the subject and the object, celebrating a wide diversity of focal points and methodological choices.

At the Umeå School of Architecture, we champion forward-thinking and an inclusive environment where holistic, transdisciplinary, and innovative approaches are essential for addressing global challenges and opportunities within architecture and the built environment. Research and postgraduate education within the department are organized into four primary thematic areas: Architectural design; Architectural history and theory, and critical studies; Landscape and urbanism; Building construction; Materiality; and Computational design.

Doctoral candidates are supported in positioning their research within a particular field of

knowledge and its discourse, identifying gaps, contributing to the discourse and its practice through new knowledge, and participating in dialogues through various formats of dissemination. They also develop their unique research approaches and methodologies.

Furthermore, the programme focuses on cultivating the doctoral candidates’ capacity to independently advance their research and serve as significant and proficient research collaborators in projects that impact people’s environments and life situations, encompassing environmental, technical, societal, cultural, and aesthetic perspectives. Through collaboration with peers, PhD students nurture and advance their individual projects within a supportive environment of collective research in Umeå, Sweden, as well as at other universities internationally. They also engage in dialogues and collaborations with the wider society, public sector, and industry.

DArchitecture research loses sight of its conditional nature and propositional power when it takes no risk in speculation and experiment, circulates as a form of administrative inquisition over the world paralyzing architecture practice. What our current society needs is a different kind of research — one that breaks open the conservative way space is experienced, thought, produced and distributed.

This research should displace the binary dialectics of colonizer and colonized, the one against the other by introducing a third that belongs to both, the one and the other, while opening alternative horizons. Such an approach positions architecture as a vital ally of processes of emancipation addressing the multi-crises of our world today. It’s within this framework that a prospective future for doctoral researchers in architecture resides, both in practice and academy, as we face the urgent need to reimagine the world anew.

Roemer van Toorn, Professor in Architecture theory, Director of doctoral studies

The Oslo School of Architecture and Design, AHO

These reflections are made on the subject of architectural research as it appears within a PhD programme whose scope specifically includes research strands that do not define themselves as being part of architecture. Within this context, there are returning questions about what horizons should be employed to define societal relevance. Must we prioritise research that leads to immediate effects that change societal practices? How can we defend “ground-research” whose immediate significance is apparent to small, probably elite academic groups and whose immediate societal effect is harder to discern? When is it useful to bolt the word “research” onto an action of writing, or making, or designing, and when is it best to use other yardsticks of valuation?

At AHO through the 2010s we created momentum for research in architecture that contributed to the very academic field of architecture history. Since 2020 we have started to link historical and archive studies to much more pressing societal questions relating to re-use, extraction, appropriation, and circularity. We now believe that one of the values of this strategy is to train actors through PhD studies who can master the tools traditionally used in historical studies and use these

to operate at the level of architectural — or indeed wider cultural — practice. This change in emphasis is now informing the way in which we apply for external funding, for example, the recently awarded Norwegian Research Council project “Provenance Projected” (https://provenanceprojected.no ). Provenance Projected uses history to look at questions of architectural circularity. It involves PhD projects directly related to such initiatives, and within the architectural history-group we are currently training “both-and” PhD candidates who combine archival research expertise and design skills very closely.

In this endeavour, disciplinarity is essential to us. The benefits of being involved in cross- or interdisciplinary projects seem to us to depend on extremely rigorous training within the specifics of disciplines, and of sub-disciplines, at PhD level. So, we see PhD training very much as using a small and very focused research project to develop expertise in particular research tools, and at the same time to begin to understand the potential of this expertise in wider, probably cross-disciplinary processes. We think that there is a tendency in PhDs from design schools to be over inter-disciplinary — people wanting all their kinds of activities to be defined as “research” within the PhD project — and we think that this causes problems for the value of PhD training. PhD projects are probably not a very good vehicle for interdisciplinary research. On the other hand, positioning disciplinarily-focussed PhD

projects within funded higher-research projects that combine actors from practice and research, or from various research practices, seems to us very productive. Notably, in the initiative we have had at AHO to develop a prototype project for a “practice-based” architectural PhD, three out of five candidates eventually used the vehicle of a history-led monograph thesis as a basis through which to refine the thinking in relation to the architectural practice that they wished to pursue.

Within this initiative of generating practicerelevant historical research, it is also important to reiterate the use we make of the interface between masters-level teaching and PhD projects. Our group of completing PhDs have all been involved directly in teaching design within the professional master’s programme in architecture. In some cases, empirical material for the research project is generated through this interaction, but more often the teaching context provides the foil that allows the candidate to see the potentials and relevance of their project within a wider societal frame. The honing of a skills set “outside” the PhD can be very useful as a way of triangulating the importance of the PhD itself — to define what is and what is not research.

I’ve reflected so far on the limited case of our PhD candidates whose research subject is specifically architecture-related and who have chosen historical methods as a way to frame their enquiry.

Because we are a generalist programme, we have a real challenge in identifying what aspects of method are valuable to train at the programme level (archival methods are relevant for one sub-group but not for all). Our difficulty and risk is that a tradition that employs a “one size fits all” approach to the educational component of PhD education still occupies too much of our candidates’ time (we still teach 18 ECTS general obligatory courses; we aim to tailor the activities to individual PhD projects, but at the end of the day we are still teaching in the common ground of what makes research research at a general level, rather than in the skills areas that make particular modes of enquiry resilient).

We believe that certain aspects of this common-cause approach are useful: depending on the inter-disciplinary PhD group, we find that clearer understandings evolve of how knowledge is valued differently in varying fields, and these combined activities build a resilient PhD group. But we still need to understand how to value and understand the specific methods-based tutoring that goes into PhD projects within very different research contexts. We lack some tools for understanding the interface between individual supervision and programme training.

At the same time, we understand that we need, in terms of identifying and arguing for the “relevance” of PhD subjects, to identify and argue for the relevance of PhD fellows. This translates

into a question of thinking about career-development. It seems fair that in answering the question of “what tools have you gained by taking a PhD?” that we have an answer to the question “and how/ where might these be used”. This is not, emphatically, to suggest that the intellectual investment in a PhD should be dumbed down, or that projects should be predicted by a narrow definition of “societal relevance” (this weapons system; that fertilizer; those car tyres). Rather, we need both to understand ourselves, and to help our candidates understand, where are the quiet slots in which particular skills gained in focussed PhD training fit into complex cultural processes.

Tim Anstey, Professor and Head of research education

AArchitecture adjusts humans and space. As space and time are the fundamental modes of human consciousness, it is difficult to overestimate the relevance of research in architecture. The problem here is that due to the nature of architectural phenomena, it is very often not clearly understandable to the wider public. Architecture amalgamates the material reality, social codes, particular as well as universal cultural values, and power relations which usually have also strong spatial dimensions. This complex of layers and foci is not easy to unravel, but this is one of the most important aims of architectural research. The other aim, not less relevant for the culture, is to predict and speculate about the future skills and knowledge necessary in architectural education amongst the rapidly emerging technological and social changes. This means making predictions in the time horizon of 10–15 years — an almost impossible task. Until humans are structured by space and time: the phenomena of architecture remain important.

BThe material reality, social codes, cultural values, and power relations make architectural research a priori transdisciplinary. When architectural

education is focused on creative and technological directions, its research should be wider and comprehensive. This also predicts that it has to be in its entirety both cross- and interdisciplinary. Certain “full spectrum” analyses are necessary to deal with complex architectural phenomena. If we adopt the wide scope of architectural research, it becomes obvious that it cannot be disentangled within one PhD thesis or even within one “school of thought”. It needs a wide vision and background. It is not important if the students are of similar or mixed backgrounds, the essence to my mind lies in the critical mass of PhD studies in architecture and related disciplines. I am afraid, that if we take the whole Balto-Scandia area, it still lacks the critical weight to harvest the synergy created by the unified field of these PhD studies.

CThe knowledge, skills, and competencies in the education of architectural research can be summarised as erudition and a holistic world-view. In the Digital Age university education is radically changing. Much of the work is actually more effective via digital networks. What cannot be learned individually and via networks is erudition in a particular field. This needs the culture of research as well as collective guidance to understand what is essential and how is it related to the human past and future. Knowledge and skills without the world-

view remain atomised and cannot be united to the holistic understanding, necessary for architectural research. Here one also has to criticise the widening approaches of artistic research and research by design. In general, these approaches do not generate the necessary quality and scope of erudition. With the Bologna tradition, which does not favour professorships based on experience and outstanding creative work, we will face academia with missing erudition and experience in practice.

DThe Digital Age will allow us in the timeframe of five years search and summarise all mankind has written and much it has imagined. This will change the history, theory, and philosophy of architectural phenomena in a radical way. Several paradigms and discourses will be interpreted anew and several new ones will be put forward. It is a really interesting time to pursue a doctoral degree, hopefully with the necessary erudition and humanistic world-view.

Dr. Jüri Soolep, Professor and former Dean of EKA, partner of AB Medium

Royal Danish Academy: Architecture, Design, Conservation, KADK

In what follows, I will endeavour to answer the individual questions but will do so by — initially — pointing to the conditions for research training in Denmark , which, so to speak, have fundamentally shaped our work to develop a PhD programme at an architecture school.

A condition which, after thorough ministerial committee work, became the basis for ministerial recognition of the development of a research training programme at the Royal Danish Academy (a development which, on the basis of this condition, was initiated in 2012) was that we had to work according to a generally recognized research concept. In other words, we should not work with architectural research as something special, but with the acceptance that research in architecture is characterized by generic competences valid for any field of research. We had to train researchers in architecture with an understanding of what is required of researchers in any recognized research field.

This meant, on the other hand, that we could work with many different scientific disciplines in relation to architecture, which has enabled an interdisciplinarity which is a special challenge — and opportunity — in relation to the various scientific disciplines that we as an institution can involve in

research in architecture. As an institution based on a long, artistic tradition, we are aware that architecture is a special field, which is why the outlined requirements for our wish to supplement the institution’s work with the involvement and development of scientific research have given us the opportunity to work with many different scientific approaches to architecture as a supplement to the development of our artistic tradition.

The decisive challenge has been — and continues to be — to create “kinship” (Chakrabarty/ Haraway) between these different approaches: scientific and artistic, and thus to create a fruitful collaboration between differences for the benefit of the development of architecture in a world, characterized by hitherto unrecognized challenges that require this cooperation. In other words, it is my opinion that the condition that was the prerequisite for us to be able to develop a PhD programme at the Royal Danish Academy: that we work in accordance with a generally recognized scientific concept, turns out to be a very relevant advantage, which means that we as an institution can contribute to architecture now and in the future learning from many different scientifically created insights.

I mean by this to be in the process of answering the question of the societal relevance of architectural research at a time when society is becoming aware that we live in and must inhabit a “critical zone” (Latour) or an Earth System (Chakrabarty)

which our so-called modern society has previously ignored. The societal relevance is that, via scientific research efforts involving many different scientific fields, we can expand on the understanding of what architecture can be, in a time that needs this richer, faceted, cross-, inter-, and trans-disciplinary attention. This situation has been tackled with new measures in our education from the first to the third cycle. From the start of education, we work with the students’ understanding of what it takes both to create knowledge (research) and to design while involving knowledge. We endeavour to develop the students’ understanding of working with different, qualified studies of the world, which they must make habitable with architecture.

We must educate with an up-to-date understanding that architecture is a special discipline, where an understanding of both firmitas, utilitas , and venustas collaborates, which requires both specific, focused research in dialogue with, for example, engineering or social sciences and an understanding of the knowledge gathered in an architectural proposal. In this way, what we develop at the research level becomes relevant for the education from the first year of study. This synergy is extremely important for both education and research to thrive at the institution.

Let me conclude by pointing out that involving research in education in a school with a long artistic tradition is characterized by many differ-

ent challenges. However, it is my opinion that these challenges anticipate challenges that we as a society face when, with the involvement of research, we have to learn to inhabit the planet differently than we have done in the past. With our challenges and drawbacks — as stated it’s not an easy task without obstacles — we are at the forefront of reaping experiences that others can benefit from. At least that’s the hope.

Henrik Oxvig, Head of the doctoral programme

A

Research in architecture has the potential to be(come) an invaluable partner to address the complex crises, which we face today. I would like to support this premise with three arguments. First: An important assumption is that the response to current crises requires a combined analysis from different domains. The diversified research environment in architecture can be accommodating here, since it covers a versatile spectrum of expertise and approaches, based on engineering, design, arts, history, and social sciences.

Another crucial advantage would be that many researchers in architecture are trained in inter- and transdisciplinary learning trajectories, which stipulate collaboration with various experts. Therefore, they needed to develop skills to realise cooperative efforts. Last but not least, in current crises, we are often confronted with ill-defined problems. Also in this regard, architects and designers have an essential advantage, given that they are trained in (re-) defining the question first: the problematisation is the starting point of a process of “design” and of “creation”. On a personal note: I would be far more selective when defining the focus of research in architecture. Not all research topics are equally relevant to society, whereas the

challenges for society and also for architecture are immense.

BWhile the benefits of cross-, inter-, and transdisciplinary research approaches are evident in addressing ill-defined, complex problems, the relationship between different (sub-) disciplines is complicated and holds significant complexities, risks, and challenges. Such cooperation can be very intense and time-consuming, and efforts are often underestimated. For instance, creating a shared language and understanding can be a significant hurdle that needs to be addressed already in the education of PhD students.

A major challenge is also to gain recognition for methodologies and research output that deviate from classic scientific approaches. As relatively young fields, artistic, design-led, and practice-based research are confronted with a struggle to advocate for the validity and rigour of research methods within the broader academic community. Furthermore, research across academic disciplines, as well as transdisciplinary collaborations with practitioners, also require careful consideration of process design and communication. A set of skills for effective collaboration is essential to involve practitioners, stakeholders, and end-users, leading to comprehensive outcomes.

When you are trained as an architect, there is no self-evident transition to start a doctoral research in architecture: a good designer is not necessarily also an excellent researcher. In my opinion, doctoral candidates benefit from a doctoral programme that provides the necessary methodological foundations (1) to learn how to problematize an issue in order to formulate relevant, sharp questions, (2) to get to grips with the diversity of approaches in a multifarious epistemological landscape, (3) specifically, to become familiar with domain-specific approaches such as artistic, design-related, and practice-based research, to understand how an issue can be investigated from different perspectives, (4) and to support the candidates in systematically analysing the research field, to be able to write a focussed rationale and a state-of-the-art overview.

Ideally, the doctoral training iterates with the feedback of supervisors to sharpen the research design. On another page, the doctoral programme should also provide insights into funding opportunities and challenges (this is often overlooked), and it can facilitate exchanges between doctoral candidates from various research groups to create interpersonal skills and a fundamental openness towards inter- and transdisciplinary collaborations.

Whereas a bachelor in architecture is trained in the basics, a master’s student is skilled in more complex matters and ready to start as a practitioner (more or less ready). Through the PhD, a candidate can build an expertise on a specific issue, from a critical reflective position. In this third cycle of education, a PhD candidate excels in systematic analysis and synthesis. A disciplined observation and investigation of socio-spatial issues is relevant for academia as well as for practice. Furthermore, a PhD is expected to build a critical awareness about systemic conditions, and to be able to question the questions (this though is not always appreciated in practice).

At times, academics experience how perception works against them, e.g. when it comes to the assessment of the practical use of a PhD, or to the perception of speed in academia and in practice. While research allows one to work on a topic during several years, practice is confronted with a need to respond much faster. In my view, the combination of creative design approaches with systematic research methods allows to build fast-forward, experimental as well as rigorous modes of knowledge production. This important benefit is often underexposed.

Annette Kuhk, Policy advisor for research

AIn 1943, Winston Churchill said “we shape our buildings and afterward our buildings shape us”.1 Although Churchill’s comment was made specifically in relation to the shape of the British Commons Chamber, which needed to be rebuilt after being destroyed by incendiary bombs during the Blitz — the question at hand was whether the chamber should be rectangular or horseshoe-shaped — this comment can be extrapolated to the built environment at large. The shape and layout of the built environment create affordances. It enables and supports certain uses while prohibiting others. The shape of the built environment is thus intimately entangled with the organization and operation of society. Understanding these entanglements — and the affordances embedded in built environments — in different contexts and across different times is thus imperative.

BDifferent disciplines have different (historic) lineages. These lineages inform disciplinary views on what topics deserve attention and which methods can (or should) be used to conduct research. For instance, some disciplines have a long tradition in practicebased research, while others favour statistical

analyses. Furthermore, while some disciplines are firmly established, others have emerged more recently. Conducting research that brings together different disciplines enables these disciplines to learn from each other. It can, for instance, provoke different views on what topics merit attention and what research methods can be deployed. Conducting cross-, inter-, or transdisciplinary research can thus bring new insights to topics that have already been studied (by approaching them from another angle or through different research methods), open new research avenues, and expand disciplinary boundaries. The risk, however, is that an in-depth understanding of the epistemological foundations of specific disciplinary cultures is eroded if such cross-, inter-, or transdisciplinary research is embarked upon without carefully considering the ethos and background (and the failures and felicities) of their historic research lineages.

CGiven the contemporary information overload and considering the rapid ascendence of artificial intelligence (AI), among the key messages that doctoral education should instil in young researchers is an awareness of the partiality of sources and the situatedness of research, and an understanding of the role and position of the researcher. The necessity to raise this awareness and cultivate such an understanding requires greater attention in doctoral

education as the infamous “god trick”2 stubbornly continues to dominate academic research, including research in the architectural humanities.

DDoctoral education hones not only research but also reasoning skills and sharpens scholars’ awareness of their position in the face of broader societal questions and challenges. A potential drawback of promoting and pursuing doctoral studies is the growing pressure on universities to award doctoral degrees and on graduates to obtain them. Doctoral education, like higher education in general, has become part and parcel of capitalist economies. To conduct research (including doctoral studies), scholars increasingly rely on third-party funding, including funding from private, for-profit organizations. This arrangement can undermine academic freedom and erode scholarly independence. Furthermore, with an ever-growing number of doctoral degrees awarded and a limited number of (tenured) faculty positions available, careers in academia have become increasingly volatile and precarious.

Janina Gosseye, Professor of Building ideologies

1 “Churchill and the Commons Chamber”, UK Parliament, https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/ building/palace/architecture/palacestructure/churchill/. Accessed 8 July 2024.

2 Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective”, Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (Autumn 1988): 575–599.

AFollowing the UK Research Excellence Framework perspective (the UK Government’s 6-yearly HEI research assessment process: www.ref.ac.uk) , UK architectural doctoral research education is required to produce internationally “original, rigorous and significant” research outcomes. UK doctoral architectural research (e.g. at UCL, Edinburgh, Newcastle, Manchester, Liverpool, Bath, Sheffield, University of the Arts London) enables doctoral communities, pedagogues, assessors, and candidates, to achieve these criteria as:

a. artefactual design, and disciplinary, contributions to professional agendas, which benefit excellence in the built environment sector and architectural industries (e.g. commercial/non-academic built design, such as: public and private commercial and cultural/public buildings; urbanism, housing and masterplans, climate, and decarbonisation design; architectural landscape design; structural and environmental, engineering; computational design; policy and heritage conservation); And/or:

b. interdisciplinary and/or experimental design outcomes which may range in innovative and transformative methods/forms/outcomes that augment, or transform, architectural design through, e.g.:

visual, written, and design artistic artefacts, poetics, voices, and performances; explicitly “situated” (cf. Haraway) political, social, environmental and climate justice agendas, together with ethical advocacy and analysis of structural social (including anti-racist, anti-sexist/homophobic/ableist), economic, environmental and conflict injustices; critical approaches to computational and technological approaches to climate change and fabrication methods; And/or:

c. architectural research outcomes/artefacts for communities external to the profession, including: vulnerable international/local communities who face structural injustice in 21st c. built environment, e.g. in housing/professional access/professional discrimination; experimental academic and cultural practices, such as those enabled by the visual and performing arts; pedagogic communities external to formal higher education; experimental and speculative design outcomes (cf. “blue sky”, “A-type”, experimental — i.e. not-applied — research outcomes).

In contrast to the traditional definitions of autonomous scientific disciplinary criteria, UK doctoral design-led education is perhaps still more interdisciplinary in its methodologies than some areas of doctoral research in other nations/regions. In part, this may be because UK doctoral educators include

high numbers of academics themselves trained in interdisciplinary methodologies (e.g. feminist architectural history and theory or in literary and visual arts practices), but also because early modes of UK design/practice-led doctoral education (now sometimes referred to as design-research, cf. Hill 2014), partly followed artistic practice-led doctoral educational principles as references (e.g. see Gray and Malins 2004), which explicitly promoted experimental practice-led (e.g. artistic, or design) research, rather than through the demonstration of traditional academic or scientific methods, as found in the social, physical, natural sciences and humanities.

UK architectural doctoral education therefore often offers a wide range of modes of research practice/method and forms of membership in the academic professional research community. On the one hand, programmes enable researchers to develop original scientific contributions to knowledge, as defined within specific professional disciplinary focii (e.g. design, urbanism, engineering, professional practice). On the other hand, UK doctoral education often promotes critical interdisciplinary innovation of these professional, legal, and or commercial categories/traditions, by nurturing doctoral communities whose agendas, methods, practices, and communities are distinctly “other”, or intentionally external to, the traditional profession commercial priorities.

UK HEI research agendas also underpin the significance of architectural doctoral education extending beyond the built environment’s professional economic agendas. As such, UK doctoral programmes may intentionally train researchers in critical examinations of architecture as necessarily structured by the intersecting “relational” (see Rawes 2013) social, economic, and methodological forces or agendas, and which, therefore, may also reflect the urgent contemporary international challenges (also see UN habitat, climate, and anticonflict policies).

CUK doctoral programmes normally follow a 3+1 year model of completion: 3 years of research inquiry + 1 year of “writing up” (sometimes called “completing research status”). Note, however, that new UKRI and EU funding awards are beginning to put pressure on doctoral completions within 3 years. UK doctoral education is distinct from Scandinavian and many EU providers because programmes will support funded and unfunded students equally. UK HEI does not require that doctoral programmes only accept/educate funded “scientific” researchers (e.g. in receipt of institutional, UKRI, or international scholarships), and UK doctoral architectural and fine art programmes also commonly support part-time enrolment. UK doctoral architectural programmes may therefore

be very large: e.g. UCL’s Bartlett School of Architecture currently has c. 135 enrolled researchers across 5 doctoral parallel programmes: architectural design, and architectural/urban history and theory (each may include landscape and environmental-led research); professional practice; computation and digital design; space syntax. Such large communities of researchers and supervisors support both interdisciplinarity and disciplinarity, e.g.:

a. high variety of intake student skills: architecture, art, design, built environment, fashion, film, illustration/graphic design, theatre, landscape, humanities, social science, engineering, medicine, manufacturing;

b. diverse alumni professions: international academic lectureship/postdoctoral appointments in architecture, social science, humanities, arts, and engineering; international architecture profession, built environment sector, policy, heritage, academic publishing and architectural criticism, visual arts, museums, curatorial and creative sectors, cognitive design fields, journalism, and communications.

In addition, all enrolled doctoral candidates (full-time, part-time, funded/unfunded) have employment rights to apply to relevant advertised PGTA or teaching fellowships in their respective institution or in other HEIs (i.e. no restriction is placed on which doctoral cohort can apply for relevant jobs, nor is there a requirement that doctoral students must have academic appointments during their PhDs).

UK HEI and REF2029 commitments to improving EDI (Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion) in the sector, means that architectural doctoral education is required to continue to reflect these structural legal and social equity standards more fully and explicitly, e.g. in REF2029 “People, Culture, and Environment” submissions (also see Athena Swan Charter www.advance-he.ac.uk/equality-charters , and UK Equality and Care Laws, 2010 and 2011). Doctoral architectural education must therefore demonstrate that its student intakes, its scientific methods and practices, and its community (students and academic supervisors) reflect these concerns, and constituencies, including anti-racist, anti-sexist/ homophobic/ableist, agendas and recruitment. Recent high-profile reports on discrimination and harassment in the UK academic sector (e.g. UCL’s Howlett Brown Report), the UK HEI sector reliance on Overseas student fee income, the now-previous UK Government’s immigration restrictions on visas (still in place, as I write), highlight the structural political and economic nature of these issues.

New models of “shared governance”, ethical and equitable educational/pedagogic responsibility, and provision are being developed in the UK HEI sector, which is being reflected in architectural design departments (i.e. not exclusively located in/ specific to doctoral training). Recent examples include institutional pedagogic/research agendas at:

UAL’s social purpose agenda; UCL Bartlett School of Architecture “Shared Governance”; Newcastle’s AHRC Translating Ferro/Transforming Knowledge grant; Liverpool’s decolonial architectural history training grants; London School of Architecture’s professional access principles; Architecture Foundation’s New Architecture Writers’ programme.

Peg Rawes, Professor of Architecture and philosophy, Director of research

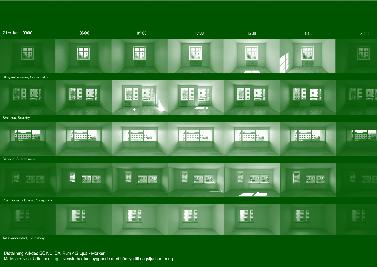

The requirements for pursuing doctoral studies and for attaining a doctoral degree vary significantly across Europe and the EU — by country as well as by institution. Most EU countries require candidates to hold a master’s degree or equivalent in a relevant field. Some countries may accept candidates with only a bachelor’s degree if the candidate has demonstrated exceptional academic ability. PhD candidates are often required to submit a research proposal outlining their intended project, as part of their application, but they may also be enrolled as a junior member of a research team.

Some programmes offer funding or stipends, while others may require students to secure their own funding through scholarships, grants, or assistantships. PhD programmes typically last between 3 to 5 years, depending on the country and the nature of the research. Some institutions also offer joint PhD programmes and collaborations with industry. There is no standardized requirement for ECTS* credits specifically for doctoral programmes, but many require students to take 30–60 credits from coursework related to research methods, discipline-specific studies, and other training.

Doctoral studies in Sweden differ from those in many other countries, in that it comes with a salary and is a form of employment. The study period — 2–3 years to Licentiate, 4–5 years to PhD (doctoral degree) — depends on other institutional tasks such as teaching (up to 20%). The predominant

system of distributing research funding in Sweden — a competitive model based on applications in response to calls — means that doctoral candidates are increasingly funded through project grants (from external funders) in combination with faculty means. Studies may also be funded through collaborations with industry (which usually means studying part-time). Self-funded studies, e.g. as supported by individual scholarships and grants, are in most cases not permitted.

* Within the EU, The European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) is commonly used to measure educational attainment.

Location: Gothenburg, Sweden

www.chalmers.se

The department has three doctoral programmes: Architecture; Civil and environmental engineering and Applied acoustics. The Architecture programme currently has 13 doctoral students. Mandatory courses are taught at Chalmers centrally. Non-mandatory courses are taught at department level and students also take courses in other departments at Chalmers or in broader research networks. The majority of doctoral students have a master’s degree in architecture, but there are also a few with other backgrounds, e.g. from a medical field, social sciences, and industrial design. Funding comes largely through external funding or, in some cases, through internal university funding.

Location: Stockholm, Sweden www.kth.se

There are currently 15 active doctoral students, of which 7 are due to complete in 2025. The doctoral programme has six mandatory courses at 7,5 ECTS each. Courses train knowledge and skills in scientific theories, research methods, and communication (including participation in seminars). Students must also take one course tied into one of the research strands of the department: Architectural theory, history, and critical studies; Urban design and urban theory; Architectural design, technology, and representation. Mandatory courses are taught at KTH and/or are offered within the ResArc network. Other courses can be taken at KTH or within a broader network of universities. Most PhD students have a master’s degree in architecture, but there are also a few with other backgrounds (e.g. art history, interior design, building conservation, or urban planning). Students are increasingly funded through project grants (from external funders) in combination with faculty means. KTH no longer accepts students funded by scholarships.

Lund University LTH, Department of Architecture and the Built Environment

Location: Lund, Sweden

www.lu.se

The PhD programme at Lund has three research education subjects: Architecture; Construction and architecture; and Environmental psychology. At ABM (winter 2024–25), there are in all 13 active doctoral students: 6 in Architecture, 3 in Construction and architecture, and 4 in Environmental psychology. In the Architecture programme there are three mandatory courses: Introduction to PhD studies; Research ethics; Theory and methods of architecture research. The course part of the education consists of a minimum of 60 credits (20 mandatory and 40 selectable). Apart from the courses, every PhD student runs a personal project with mandatory seminars at 50% and 90%. Doctoral students in Architecture have a master’s degree in architecture or a corresponding background in the social sciences, humanities, or art that concerns spatial forms of expression. LTH usually does not accept students funded by scholarships (with some exceptions). PhD students are generally funded through external project grants in combination with faculty means.

Umeå School of Architecture, UMA

Location: Umeå, Sweden

www.umu.se

There are currently four PhD candidates enrolled in the department. The coursework component comprises 70–90 ECTS, combining mandatory and elective courses that are tailored to the specific needs of each PhD student. UMA offers a series of mandatory courses designed to build expertise in architecture and its research methodologies, along with courses that address general research skills in science and technology. To meet the required ECTS, students are expected to take courses both at UMA and at other universities, with an emphasis on schools of architecture within Sweden. All PhD candidates hold a master’s degree in architecture and are fully funded by the Technical Faculty at Umeå University. Three of the current PhD positions were established in connection with the appointments of two new professors and an assistant professor, while one was created as an open position. Future PhD candidates are expected to secure funding from external sources.

The Oslo School of Architecture and Design, AHO

Location: Oslo, Norway

www.aho.no

There are currently 38 PhD students in the programme, and 4–6 internally funded candidates are enrolled per year, in the subject areas: Architecture, Design, Landscape architecture, and Urbanism. The project period is 3 years, with a selection of calls that include a 4th year of teaching. Externally funded candidates may apply to be taken up in the PhD programme requiring a project proposal, supervision fit, and proof of funding for the proposed project. The majority of candidates are working within larger research project contexts, some funded by external sources. PhD students may also be funded in collaboration with employers, the so-called Industrial PhDs, or Public Sector PhDs. The PhD programme offers 18 ECTS credits for mandatory courses: research methods and cultures, state-of-the-art/literature review, writing workshop, and framing/completion workshop. An additional 12 credits are attained through elective external courses and presentations, to achieve the total of 30 ECST required. The majority of PhD students have post-professional research-level qualifications, extended research and practice backgrounds, or extensive teaching experience.

Location: Tallinn, Estonia

www.artun.ee

The faculty of architecture currently has 25 doctoral students enrolled in the doctoral programme Architecture and urban planning. 8 of these are external, which means that they don’t participate other than to defend their thesis. The average number of years for a PhD is 4 years, with additional time depending on departmental tasks, such as teaching. The programme offers and/or requires course credits of 51 ECTS (out of 240 for a doctoral degree). The majority of PhD students have a master’s degree in architecture, but several have other educational backgrounds, such as in philosophy, photography, landscape architecture, or art history. Research studies are funded as a researcher position by EKA or through an EKA stipend.

Royal Danish Academy: Architecture, Design, Conservation, KADK

Location: Copenhagen, Denmark

www.kadk.dk

There are currently 42 PhD students enrolled. The average completion time for a doctoral degree is 3–4 years, and the PhD programme is equivalent to 180 ECTS points, of which 60 ECTS should be covered by courses, teaching, and presentations at seminars and conferences. About 30 ECTS courses are offered internally per year. Courses can also be taken at other universities, nationally and internationally. Teaching at the bachelor and master level is a requirement. The PhD programme educates researchers with many different backgrounds, and projects can be related to any of the five faculties. In addition to creating an understanding of what it means to produce research-based, qualified knowledge, the ambition of the PhD programme is to create dialogue across the faculties, and to enhance and qualify the exchange between science and art. The PhD scholarships in Denmark are wellfunded but require that the studies are completed in approx. 3 years. PhD projects often involve collaborations with design studios and businesses.

Leuven,

Location: Leuven, Belgium

www.kuleuven.be

There are currently about 73 doctoral students (around 18 new students are accepted per year). The regular trajectory of a PhD study period is 4 years and research is carried out in one of four sections: History, theory, and criticism of architecture; Architecture & design; Design, engineering, construction; Architecture or urban design; Urbanism, landscape, and planning. A few PhD projects are explicitly interdisciplinary and about 10% are joint or double PhDs, in collaboration with other universities. The minimum requirement of credits for training activities (courses) is 6 ECTS. The PhD student is required to do at least five formal presentations, to teach at bachelor or master level, and to present at conferences. Most students have a master’s degree in architecture, engineering, interior architecture, urbanism, or urban planning. The majority (approx. 80%) has a full-time employment, mostly funded by external research funders at national or EU level. Studies may also be funded by means acquired by the supervisor and/or through the university. A small share of students has a part-time employment or receives a bursary from their home countries (e.g. from Pakistan, China, Indonesia, or Luxembourg, as well as Global South scholarships).

Location: Delft, Netherlands

www.tudelft.nl

There are currently about 60 PhD candidates enrolled in the department. Courses are offered from which PhD students can choose, having to gather 15 ECTS in three different categories: discipline-related skills, research skills, and transferable skills. The total amount of credits to obtain is 45. All PhD candidates have a master’s degree in architecture, and about 60% are self-funded. We cannot apply for institutional funding (from TU Delft) or national funding (from the Dutch national science foundation) for PhD scholarships. PhD candidates typically apply to other funding bodies, such as from their home country, or from private funding bodies, such as the Volkswagen Stiftung or the Gerda Henkel foundation. Some PhD candidates are employed on larger research projects that have been applied for by a senior member of staff.

UCL, The Bartlett School of Architecture of the Built Environment

www.bartlett.ucl.ac.uk

There are currently about 135 enrolled PhD students across five parallel programmes: Architectural design; Architectural/ urban history and theory; Architectural practice; Architectural space and computation; Architecture and digital theory; Space syntax. The study period is typically 3–4 years. PhD students are expected to partake in activities and present their research at regular intervals, and the programme holds a variety of seminars that target essential skills and allow for dialogue and exchange. Although the focus of a PhD is primarily on independent research leading to a dissertation, UCL encourages students to engage in transferable skills training, which can involve around 60 ECTS credits worth of activities over the course of their studies. Students are expected to audit postgraduate programmes in Architectural history, Situated practice, and Urban and historical environment modules. The educational background of PhD students is very varied; students come from architecture, art, design, fashion, film, illustration/ graphic design, theatre, landscape, humanities, social science, engineering, medicine, and manufacturing. Programmes support funded and unfunded students equally. Grants and scholarships are offered through UCL or external sources.

After a period of intense preparations, The Swedish National Research School in Architecture (ResArc) started in 2012. It originated from a meeting held in 2009 in Stockholm, where representatives of the four Swedish schools of architecture took the decision to approach the Swedish funding agency Formas through a two-step application strategy. The first step would be stating an interest to do preparatory work and elaborating common ideas, followed by a second, full-fledged, concept for a future research school with elaborated plans of activities: courses, seminars, retreats, lectures, etc. Apart from a kernel of representatives from the four Swedish schools, the ensuing application also included names and schools at an international level for future cooperation.

The initiative followed an international evaluation of Swedish architectural research (commissioned by Formas in 2006) that came up with mixed conclusions. On the one hand, it was appreciated how research in Sweden was integrated with practical and societal needs, but it was also seen as suffering from the low mass of publications in architecture-oriented research journals, hence only sparsely taking part in an international academic community concerned with and forming the field of architecture theory. To deal with the situation, Formas decided to support two strong research environments (Architecture in Effect and Architecture in the Making) and, above that, one research

school. It was decided that ResArc, in cooperation with the two research environments, should aim to improve the quality and training of theory and method in up-to-date architectural research.

In Sweden, similar to in many other countries, research education centres on developing an individual PhD project combined with a set of courses. As the course part allows for the individual student to include external courses (beyond those provided by the local faculty), the field of cooperation lies open, between faculties and between seats of education, nationally and internationally. The PhD student’s possibility to choose courses, and also in some cases co-supervisors in their individual projects, increases the potential to create a well-tempered, widely recognized, critical, and transparent sphere of knowledge, while also acknowledging the formal requirements stated in the Swedish Higher Education Ordinance.