CLAY CITY

Alexander Brodsky Artist in Residence

Amsterdam Academy of Architecture

Alexander Brodsky Artist in Residence

Amsterdam Academy of Architecture

From Table to City Foreword

A large empty table stands in the courtyard of the Amsterdam Academy of Architecture. Almost square but not quite, it measures 8.75 by 10 metres. It is winter. As it rains, small puddles form on the dark table top. The water reflects the chestnut tree branches and the patches of blue sky between the grey clouds. The table waits as time passes by; an imaginary city is in the making.

The city still exists in the students’ imagination. They are shaping the city’s building blocks with their hands, using Chamotte clay, at a scale of 1:300. Working only from memory, the students model the clay into houses, flats, bridges, churches, railway stations, office high-rises, museums, factories, schools, swimming pools, an airport, a zoo, a stadium, and so much more of what makes a city a city. The students are hard at work within the Academy walls. While the table in the courtyard patiently awaits.

Then, a short Russian gentleman wearing a red coat climbs onto the table, chalk in hand. He tentatively draws some lines, erases them, and draws them again. A river divides the table top into two, the contours of islands appear, neighbourhoods take shape. He adds more lines, until the plan of the city feels complete.

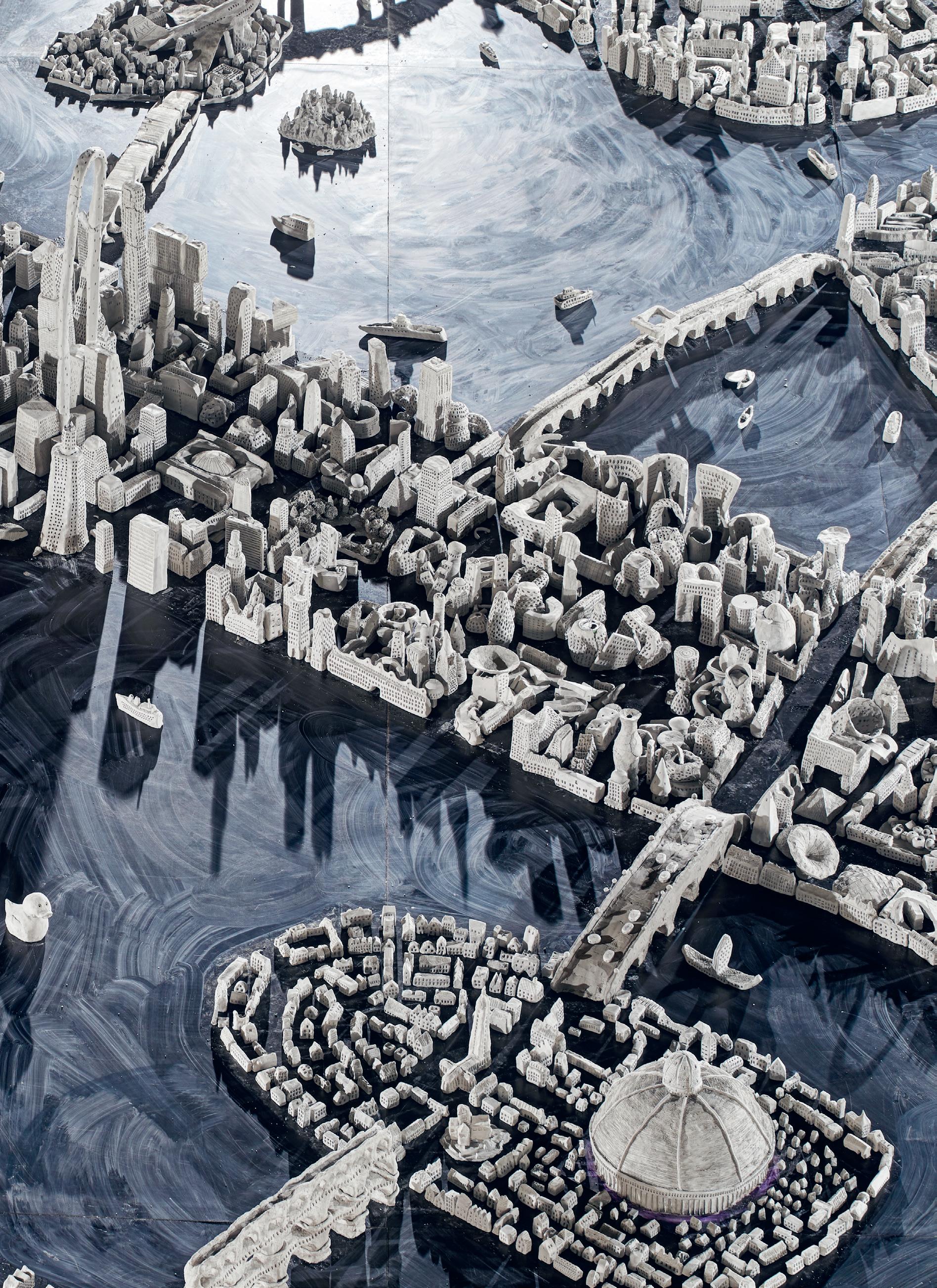

Finally, the moment has arrived. Students emerge from all corners of the school bearing large wooden trays full of small clay buildings, like platters heaped high with delicacies. They slide the trays onto the edge of the table. The building of the city commences. The gentleman in the red coat is Alexander Brodsky: architect, artist, and artistinresidence. Together with the students he picks and chooses elements, places and repositions them, until all the clay buildings have found their place. The city gradually grows and fills the table: office blocks down-town, residential neighbourhoods lining long streets, industrial parks at the perimeter, museums and schools dotted around, plus a railway station. Finally, the bridges that connect the different city parts. Despite the cold and rain, work continues unabated, even into the late hours when construction lamps are brought out to illuminate the emerging city.

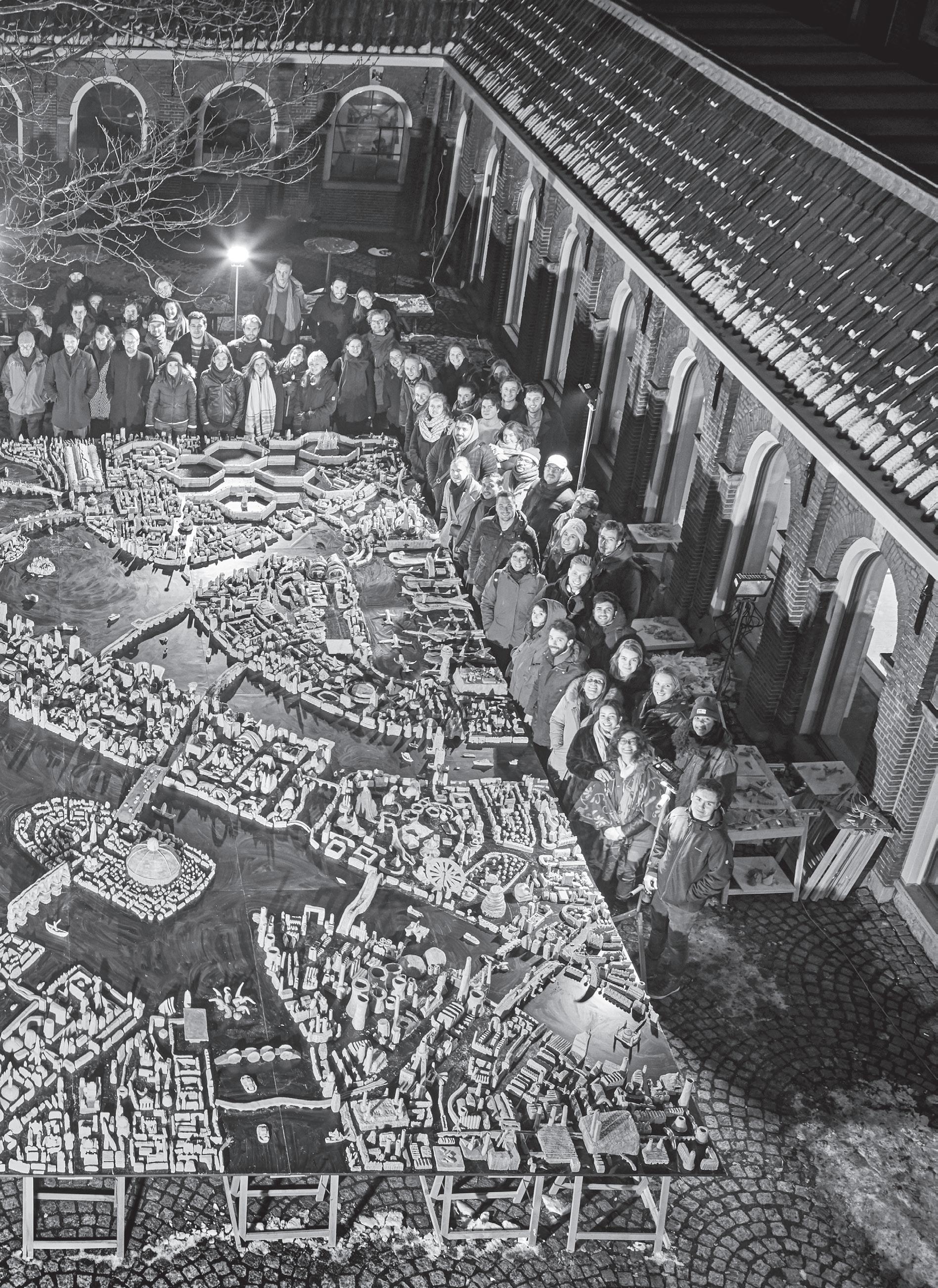

The final day: 25 January 2019. The Academy building resounds with the music of Dmitri Shostakovich: String Quartet No 7, followed by a prelude, an elegy and a polka. The performance by the renowned Brodsky Quartet celebrates the creation of this new city. Three violinists and a cellist captivate the audience in the packed hall. After thunderous applause, the courtyard quickly fills up with people, eager to see the city of clay: Alexander Brodsky with his family, students, Jan-Richard Kikkert, lecturers, invitees, academy staff, the musicians. Looking intently, gesticulating, taking photographs, attempting to recognise familiar fragments of this clay cityscape. The empty table has transformed into an imaginary city; one that will live on in the memories of those who experienced it.

Madeleine Maaskant Director, Amsterdam Academy of Architecture

Introduction

This publication presents Clay City, the 2019 Winter School at the Amsterdam Academy of Architecture led by the Russian architect and artist Alexander Brodsky. He was invited as an artistinresidence as part of the AIR programme of the Amsterdam University of the Arts. Together with Brodsky, 136 first and second-year students worked tirelessly from 14 to 25 January 2019 to collectively build an imaginary city of clay. Temporarily occupying the Academy’s courtyard, it was an impressive sight: a vast, dense cityscape handmade with an incredible wealth of detail. It took us on an architectural tour through history from ancient Rome to future Amsterdam. Then left to the Dutch elements for six weeks, the city started to disintegrate. This edition of the Winter School was not about choosing a winning presentation; instead it centred on the idea of making something that exceeds the individual to achieve an end result to be collectively proud of.

The opportunity to invite Alexander Brodsky to Amsterdam presented itself during our annual European tour to Russia in 2018. At Nikola Lenivets Park, 175 km south west of Moscow, we saw two of Brodsky’s pavilions among the landscape installations: Rotunda, which was made from salvaged doors and construction elements, and Villa PO-2 built from recycled concrete fence units, the most ubiquitous construction element in the former Soviet Union. These pavilions evoked a poetic quality that I recognised from Brodsky’s fantastical etchings which incorporated history, depth and imagination. Later that week, Brodsky gave us an introduction to his work at his office, and we visited an exhibition that showed his drawings beside Piranesi’s – the effect was overwhelming. Themes in Brodsky’s work such as the notion of history, circularity and vision fitted well with what I wanted the students to explore for the upcoming Winter School.

Initially, Brodsky was slightly daunted about the fact that there would be 136 students in the group; this is when he thought of a collective project to build a city out of clay. It was about creating something together that no one could achieve on his or her own. I believe it is important that students learn to collaborate and the Winter School was the ideal opportunity to do this with a large group.

The plan to build a clay city was settled, but we needed a site for it – and a large one at that. After scouting around Amsterdam for locations, we realised that our own courtyard was ideal. We built a table of 28 standard concrete form plywood panels (1.25 × 2.50 metres), so the model measured almost 90m2. For the base we reused material from the previous graduation show, staying true to Brodsky’s approach.

At first the students were slightly puzzled about Brodsky’s brief to make 1:300 clay models of buildings from memory, but carefully followed the instructions. Some days later the Dutch antiauthority mentality surfaced and the students started interpreting Brodsky’s assignment in their own way.

By that time the city became truly a work of collaboration. The intense production sessions were peppered with additional programmes such as a lecture by Prof. dr. Martijn Meeter about human memory, and a screening of Brodsky’s favourite film July Rain, a 1967 Soviet film directed by Marlen Khutsiev which portrays Moscow in a period of apparent détente, paired with film fragments about Amsterdam curated by Jord den Hollander. As drawing is a crucial part of his work, we asked Brodsky to make a drawing for the Academy. Parallel to the clay city outside, Brodsky drew a 10 meter long abstraction of a city inside – a section of the drawing is featured on the inside cover of this book. We also asked Robbie Cornelissen and Carlijn Kingma to give a drawing master class, where the students made two drawings parallel to Brodsky’s to reflect on the Winter School. In the meantime Brodsky steadily worked on his own immense drawing, stopping only to enjoy his daily herring.

Due to the Academy’s concurrent model where students engage in professional work by day and attend class in the evening, the classrooms were empty until 6pm. This gave us the opportunity to quietly make rounds through the building where we saw the number of clay objects steadily accumulating – there were thousands of pieces. Brodsky carefully observed the students’ work, imagining what city he could make of this. At a certain stage he requested some larger objects such as a train station, power plants, an airport and a hippodrome. Some iconic works appeared: Libeskind’s Jewish Museum in Berlin and OMA’s CCTV headquarters. But also the Sydney Opera House, Mies’s Nationalgalerie, the Battersea Power Station including Pink Floyd’s flying pig, Oscar Niemeyer’s Igreja São Francisco de Assis and Bjarke Ingels’s VIA 57 West.

When we figured there were enough models, we asked the students to bring and arrange their pieces by size on the tables around the courtyard. This was an impressive moment because the clay creations just kept coming and coming – there seemed no end to them. By then everyone was curious to see what all this would lead to. Brodsky drew a rough layout of the city on the table – for him a city always starts at a river, so water became the main structuring element. By this time it became clear that we would need a lot of bridges.

The models showed the imagination but also the personalities of the students: neat, provocative, meticulous, ambitious. The clay beautifully merged all these individual qualities into one magnificent cityscape. The buildup of the city also generated spontaneous interventions such as a hill that suddenly appeared in one corner. The level of precision was apparent in a candid movie. While assembling the neighbourhoods, one of the students – who didn’t know he was being filmed – played the quality controller. He checked whether the models were made carefully enough; those that didn’t make the cut were tossed into the cooling tower.

The end result looked familiar at first, with its mass of pitched roof buildings, as Brodsky instructed. But like in Italo Calvino’s Le città

invisibili this model doesn’t represent a real city but an idealised version. The true meaning of the work became clear in the weeks after it was finished. Exposed to the extremes of the Dutch winter, the clay started to ‘melt’ and the city fell apart. Almost symbolically the dome of Albert Speer’s Volkshalle fell first. Bridges collapsed, highrises toppled, the city was the site of a terrible fate, vanishing like the fading frescos in Fellini’s Roma. The deterioration continued: familiar buildings dissolved, little remained of the aeroplanes and the site resembled pre historic remains of a wooden settlement. This decay symbolised the passing of time, or as Brodsky put it: we come from clay and we return to it, a perfect cycle. The project became a portrait of this generation of students who used their memory and imagination to express what they find important.

I wish to thank Alexander Brodsky for his im mense contribution, Madeleine Maaskant for her support, the Amsterdam University of the Arts for making this possible, everyone that helped produce (and clean up) the Clay City, and of course the students who gave two weeks of their energy and enthusiasm to make the dream of this magnificent city a reality.

Jan-Richard Kikkert Head of Architecture, Amsterdam Academy of Architecture

In the lecture hall, Brodsky ‘live’ sketches the plan of the Clay City.

In Conversation With Alexander Brodsky: Clay

Interviewed by Jeanne TanJT How did you start working with clay?

AB There was this huge sculpture factory in Moscow where I was working for many years, it doesn’t exist anymore. At that time in the late 1970s it was an important place that made models of the main monuments in the Soviet Union like huge statues of Lenin and soldiers. They made the models in 1:1 out of clay, then made a plaster mould of it and sent it to the factory to make a statue out of bronze or stone. I spent a lot of time making my own small objects in this factory and was really impressed by the clay. Tons and tons of clay were used and reused every day for these sculptures. There was this amazing machine to mix the clay. You have to understand that clay is a material that can be used forever if you don’t fire it. Just dry it, add water, it melts and is mixed with this machine and then it can be used over again. I was so fascinated with this material.

JT Was it a special kind of clay?

AB Yes it was a special kind of clay, I haven’t seen it anywhere else. After the factory closed I never saw it again. It came from a place near Leningrad. It was not grey but a beautiful light green. For some reason they used this type of clay and they had a huge amount of it in storage. I was using this clay every day, and the funny thought occurred to me that this clay was all the time circulating in the factory, so that every piece of clay could be anything, like Lenin’s nose or a soldier’s leg. Because you use the same clay, melt it, mix it, dry it, so on. So each time I took a new piece of clay I thought it could have been 200 different things before, and now I’m making something with it myself, which was interesting. I started using clay more and more, I made some exhibitions in the 1990s with clay objects and installations in Moscow. The Grey Matter exhibition was in New York in 1999. Somehow clay became one of my favourite materials. I never fired it. I just left it to dry, and sometimes I reused it.

JT Why did you leave it unfired?

AB I liked this beautiful texture, this beautiful feeling of fragility. The feeling that it’s dust, and now it’s a piece of art but it can become dust again, and it keeps circulating and be reused over and over.

JT How would you compare the process of working with clay and making etchings?

AB Etching and clay have something in common, it’s difficult to explain – they look good together. When I started working with clay I didn’t make etchings anymore because I didn’t have space to do it. For many years I didn’t make etchings, but I always went back to clay.

JT And the clay cities?

AB The city first appeared in Moscow in an installation in a gallery called Coma. At first I didn’t think about making it from clay, originally the idea was to make the city out of sugar so then it could melt into water. But sugar was not the right material because it would dissolve too fast and the city would have to be pre formed somehow or made of sugar cubes. So finally I decided to make it from clay. Somehow this

was the beginning of a long period when I made a lot of things in clay. After Grey Matter I had an art commission for a nursing home in the Netherlands, where I made a number of clay objects.

JT Did you experience the city in a different way while shaping it from clay?

AB I’ve built the city three times previously: once in Moscow and twice in Milan. The main thing I remember was this amazing feeling of working alone in the gallery, building everything myself. It was this wonderful feeling of creating a real city, changing the streets and looking at the city from different perspectives.

JT What was the idea behind the Coma installation?

AB The main thing I wanted to say with Coma was to represent the city as a patient on a surgery table in hospital, where doctors do something bad to the body of the city. So it was mainly about Moscow and the bad things that have happened to Moscow for the past years, as with many other cities. On both sides I placed medical needles with black oil and video fragments that I made of the city. This black oil started dripping, the city was sinking. People who saw the exhibition in Moscow said different things: it absolutely looks like Barcelona, another said Venice, others said something else. The city didn’t flood completely during the exhibition because we didn’t have enough time, but by the end it was half sinking in the oil.

JT You grew up in Moscow. What fascinates you most about cities?

AB Usually I look for surprises in every city. You turn the corner and see something you don’t expect. Moscow used to be full of surprises but day by day they changed everything, destroyed old parts of the city and I became less and less surprised. Contemporary architecture in the way they use it in Moscow doesn’t give me surprises anymore; it’s a very personal thing. What I used to like about Moscow was this strange unpredictability; you find some corners, yards, layers of different times and so on. In every city it’s more or less the same. Now in the city centre, they take an area that was complex, full of small scale streets and little yards and then destroy it and put one or two buildings there instead: that becomes too simple, it changes the space. Before it was like a whole world. Now all you see is just a small piece of space with a couple of buildings and nothing more.

JT The clay cities seem like an entire world, mysterious, surprising and intriguing.

AB That’s partly because of clay itself, the texture, it’s very alive. You make something with clay, put in simple windows, then it’s a building. It has some life in it, which is mysterious. When there are thousands of buildings, of course it feels much stronger. In a huge city, you find yourself inside this world and get lost in it somehow.

JT How has your relationship with the city evolved during your career?

AB I never moved away from Moscow, I grew up there and I still live there except for the few years I spent in the US. I never left the city. So I can see all the changes that happen day by day. Moscow is a very different city now. I remember Moscow from

the late 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, it felt completely different. The atmosphere was very cosy. It was a huge city but somehow cosy. Some parts were like a big village in the centre. There were some really wild places near the Kremlin, big courtyards that were like lost worlds. But now it’s not possible to find these sorts of places anymore. Of course it happens to all cities; sometimes I’m really sad about this atmosphere we’ve lost.

JT How did you start making clay facades?

AB Some time ago, I was preparing an exhibition with clay models and I made a sketch of the gallery with clay models on tables. I thought we should put something on the wall. I made some drawings on paper and suddenly I saw that my picture also looks like a clay object on the wall – I thought why not? Why can’t I make a clay drawing that hangs on a wall like a real drawing but be made of clay. So I made a few things and I understood it was possible, even with transportation. They are very fragile, but we’ve sent them to different places, to London, Berlin, even to a museum in Sydney. As long as you don’t drop them…

JT Does this flat format show the material in a different way than when it’s three dimensional?

AB Yes it gives a different impression. You look at this piece on the wall, you see the texture, you see how the clay is all cracked. The first time you see it you don’t know what’s inside: a very thin metal structure holds it together. It’s quite strong.

JT You describe clay as a material that can be used for making memories as physical objects. Can you tell us more about this idea?

AB Clay is very easy to work with, physically it’s a soft material. If you know how to use it, you can make absolutely everything, even huge complicated structures. You work slowly and carefully, knowing the nature of clay, with no structure inside. Pottery makers can make huge hollow clay pots, adding layer by layer. It’s not like working with stone where the physical part takes a lot of time and you need special tools. All you need is a piece of clay, your brain and your hands and you have it. All together this reminds me of making memories. I’m sitting, recalling images in my head, my hands are looking inside my head and I reproduce images in this soft material. The neutral grey colour reminds me of memories when you don’t think in colour but in black and white like old photographs. These things together and the grey clay are a symbol of making memories as physical objects. When an object is still wet, you can keep adding and changing it. When you’re satisfied with it, you leave it to dry and it becomes one of these memories.

JT Are there new ways you want to experiment with clay?

AB At ETH Zurich, where we made another smaller city, some students fired the buildings at a very low temperature. Suddenly I saw that the clay looked very beautiful; it became darker with a nice grey colour. It was somewhere in the middle – it had not become ceramic yet, so it was still clay but much stronger. It’s complicated to find this exact temperature. So I’m thinking of doing something with this process, to make something a bit harder that looks like it has just dried but is not so fragile.

December in Florence

There are cities in this world to which one can’t return.

The sun beats on their windows as though on polished mirrors. And no amount of gold will make their hinged gates turn.

Rivers in those cities always flow beneath six bridges.

There are places in those cities where lips first pressed on lips and pen on paper. In those cities there’s a richness of scarecrows cast in iron, of colonnades, arcades.

There the crowds besieging trolley stops are speaking in the language of a man who’s been written off as dead.

Joseph Brodsky 1