6 minute read

VASILI VIKHLIAEV

THE UNLIKABLE I

ENGAGEMENT WITH THE FOREIGN ELEMENT

Vasili Vikhlaev (1983 Moscow) is a Russian born, German based filmmaker. His artistic background is music, documentary directing and editing. He graduated from ZeLIG School for Documentary in Bolzano, Italy and was part of the Script-Lab (Drehbuchwerkstatt) at the Munich Film Academy, where he is a part time editing mentor. Vasili uses the camera as a tool to bump into, confront and wander around areas of himself and his surroundings. Can the camera be blamed for this unlikable character? Can the camera be likable itself? Vasili uses filmmaking to explore family relationships through play and dialogue.

vasiliv@gmx.de vasiliv3.wixsite.com/researchpublication

THE UNLIKABLE I - DEVELOPMENT OF A CHARACTER I was taught two ways to breathe during my early childhood: while speaking Russian and while playing the accordion. Then we moved to Germany, and I kept playing the accordion. The German language fought for supremacy, twisting itself around my mother tongue, eventually trading places. I noticed it for the first time when I involuntarily cursed in German: Scheisse! сука!

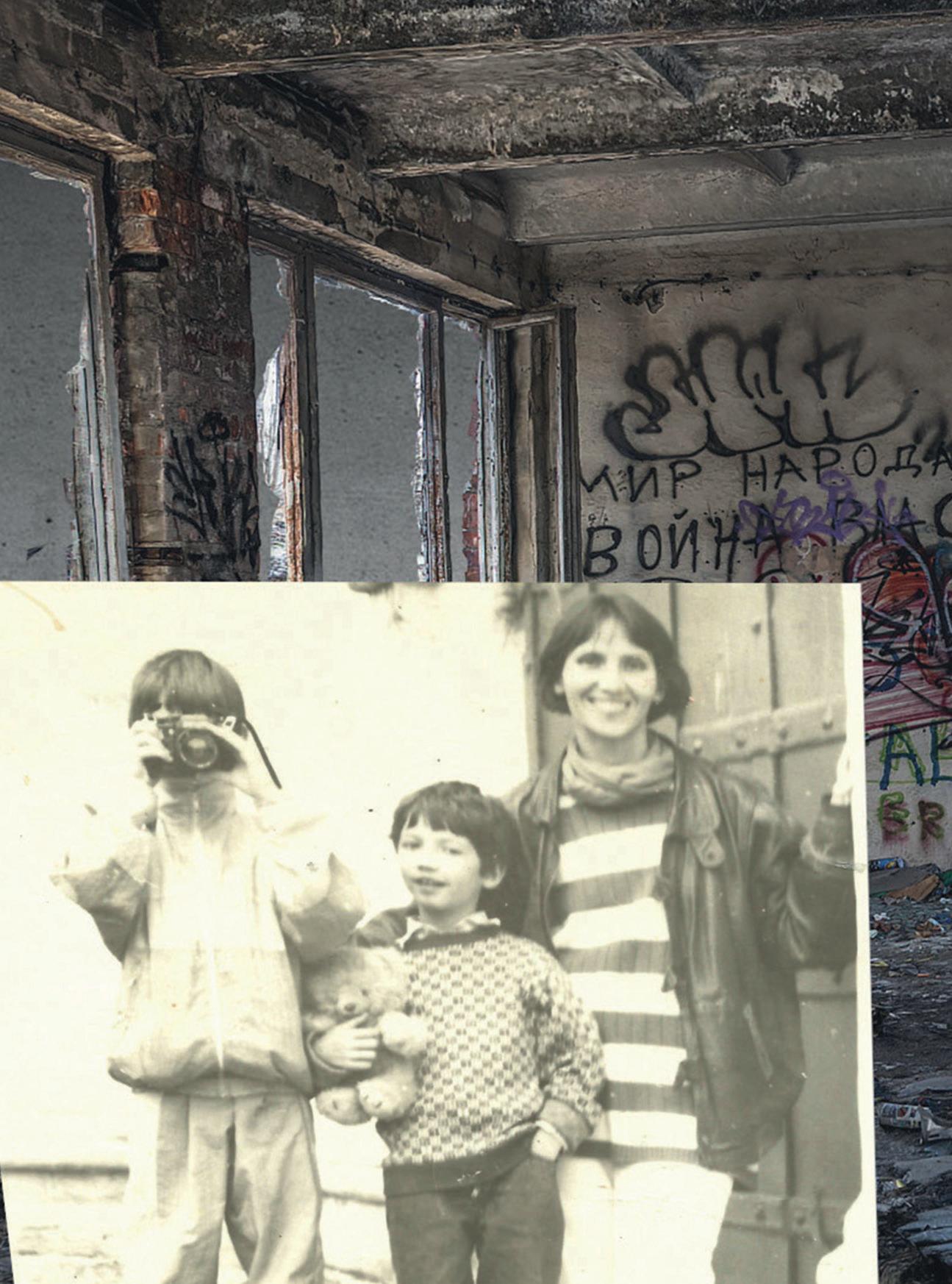

As a child I never knew what to do with my hands when I got nervous. Trading the soviet-bunkers for posh Munich made my hands very nervous. Everyone seemed aloof and so effortlessly stylish. I never knew whether my clothes or hairstyle were cool enough for this cool new home. The camera became a kind of cure against these insecurities. Something to hold onto, to focus on and most importantly, to hide behind. The camera became a shield, a protection and an instrument to dream of proximity - at a distance. Filmmaking became a distancing practice for me. Investigating childhood memories, already at a distance, through the lens of my distancing camera: somehow, I felt my memories come closer.

When I was a Moscow-City child I had a gorgeous red warrior-shield, made of cheap Soviet plastic (it smelled of iced motor oil). My best friend had exactly the same shield. We used to run into each other with our shields. Whoever fell backwards, lost.

(I usually won, but not always)

A game for boys who could not hug and had to use a form of violence to experience some kind of bodily contact. The impact was the highlight of the game, the ersatz intimacy. The impact was the purpose and the shield was the point of connection. The shield enabled the impact in the first place - by cushioning the violence of the collision. Just like boxing gloves are the necessary condition for full contact fighting.

(What I loved most about boxing was the heartfelt hug of your opponent after the fight)

((I often wonder why I cannot hug my brother?))

My foreign self appeared after my self became foreign. The accordion remained the solid, unmovable language.

“When I feel an inspiration, I die of fear because I know that once again I’ll be traveling alone in a world that repels me. But my characters are not to blame and I treat them as best I can.“

Clarice Lispector from A Breath of Life. the alpha douche bag / the jealous lover / the condescending brother / the pick-up artist / the coward / the patriarchal asshole What is his morning routine like? Does he skip breakfast, like I do? Does he do his own laundry or does he ask his mother, because he could never be bothered to learn how to use the washing machine?

Who are these characters? What are these labels? Did they exist before cinema was invented? Were they part of me before I discovered filmmaking?

The first time I met my inner asshole was when saw myself on film footage after I had turned the camera on myself for the first time (a year ago). I cringed when I saw my stonecold face next to the vulnerability on the face of my little brother sitting beside me. Who is that condescending prick?

My artistic research is like this: I use my camera as a shield to run against all that scares me: - the block of ice that grew between me and my brother and between me and other people (and between me and my self)

and:

- the parts of me that would prefer to be forgotten: the alpha douche bag, the jealous lover, the condescending brother, the coward, the guilty, the shameful… the unlikable character, the despicable me-man, formed at the intersections of capitalism, xenophobia, patriarchal gender roles and private insecurities.

I use filmmaking as an interrogation technique to explore the brutal reality of social roles and hierarchies as they manifest themselves in me, my family structures and all other relationships.

The camera is more than just a passive observer. Sometimes the protective layer of the lens is needed to face the things that make your hands sweat: the parts of yourself that drive you mad or cause you shame. The unlikable character appears on film footage. Where does he go from there?

Something happened between me and my brother around that time. I don’t know what exactly. Our estrangement runs deep and is layered. I’m peeling a half-rotten onion.

Can I use filmmaking as a tool to start the dialogue? |I record a video letter for Vova and let him reply.

Vova: Could you maybe not smoke? Me: Relax. It’s just smoke. nothing will happen to you...

(I never even look at him)

Me: Let’s reverse the dynamics. You teach me salsa dancing. You’ll be the master, I’ll be the student. I want you to be in charge! Vova: If that’s what you want… (…) Vova: 1-2-3- and on 4 you stay still. The fourth beat is a pause. (…) Vova (smile): Because, you know, Cubans love to take breaks. Me (smug smirk): that’s racist. Vova (flustered): No, it’s not. I mean, everybody likes to take breaks. Vova remembers our stepfather calling us “faggots” because we played with dolls. (I don‘t remember that...) he also remembers me smashing his toys shortly after.

(I don‘t remember that either...) ((Was that the birth of the alpha douche bag?))

I’m filming our family cat being gentle and caring to my brother. Does it make my filming “gentle and caring” by association?

The theoretical foundation of my work is critical theory and feminism. bell hook’s book The Will to Change has drastically influenced my thoughts about the toxic mask of patriarchal masculinity and has fueled my desire to rethink and transform my masculinity without giving it up entirely.

Another big inspiration for me was Ben Almassi’s paper Feminist Reclamations of Normative Masculinity: On Democratic Manhood, Feminist Masculinity, and Allyship Practices (2015)

Almassi suggests to adapt the practice of allyship to the feminist cause that is grounded in feminist values as a new form of normative masculinity. An ally is a supporting character who doesn’t claim to be at the center of the struggle. He occupies the margins and takes pride in helping to achieve justice and equality. the good-hearted saint-like figure is the main character of the novel, even though he always plays the supporting role in the stories of his brothers. He doesn’t drive the plot, he reacts, supports and analyses.

On Wikipedia Alyosha is described as “immensely likable”, but rumor has it that Dostoevsky planned on turning Alyosha into a revolutionary against the Czar in the sequel novel, one that Dostoyevsky could not write because he died.

Alyosha’s transformation from a monk to a revolutionary was never written, but it makes sense, considered his position as the radical ally.

I want to understand what is the potential of the (immensely) unlikable character. Can he be an ally, a supporting character as well? My research is still ongoing.

This echoes Dostoevsky’s last novel The Brothers Karamazov, in which the author makes clear that Alyosha,