8 minute read

ALBERT KUHN

FUTURE NOSTALGIAS

Albert Kuhn (1986) is a filmmaker from Barcelona. He graduated with a Bachelor in Journalism (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona) and studied for three years in the Cinema School of Catalonia (ESCAC). His work focuses on the relation between the personal and the political.

His film Abdala Lafdal (2016) has been screened in festivals internationally, and his interactive project Vertical / Horizontal (2015) received mass media coverage in Spain. He has also worked as assistant director and producer for artists like Jordi Colomer, Iván Argote and Marcel·lí Antúnez.

www.albertkuhnbosch.com

[This text is the first chapter from the research publication “Future Nostalgias”]

The 1st of December of 2017 I woke up at 5AM and watched, non stop, the 21 hours of home videos that my father had filmed during the childhood of my brother and me. Watching these old tapes gave me a deep feeling of an absence being created (or at least manifested) by the act of filming: the absence of the presence of my father when he filmed. Filming in such a way, I felt, created the conditions for nostalgia in the future. In other words, the absence that the act of filming created in the past was the reason for my present nostalgia. A desire to go back to the time of the images, to a feeling that maybe was never there.

With regards to watching the tapes in a row, an editor told me: “I don’t think that is an experience any human being should have”. She was right to the extent that when I finished, I felt bad for having condensed all my childhood into a few hours. What was really disturbing, however, was that nothing really strange happened. I had expected such an experiment to bring some insights about my family history and me. Instead, the images were only a support for memories that I already had. Why did I think that in these tapes there was something to be found out? What remains relevant, though, is the gesture of watching the tapes in one go.

I always had the feeling of having a bad memory. Compared to some of my friends, who can recall many details about their childhood, I could barely remember a few moments. I had hoped that the tapes would trigger some hidden memories. That was not the case. Nonetheless, three shots were very telling. A few seconds among 21 hours.

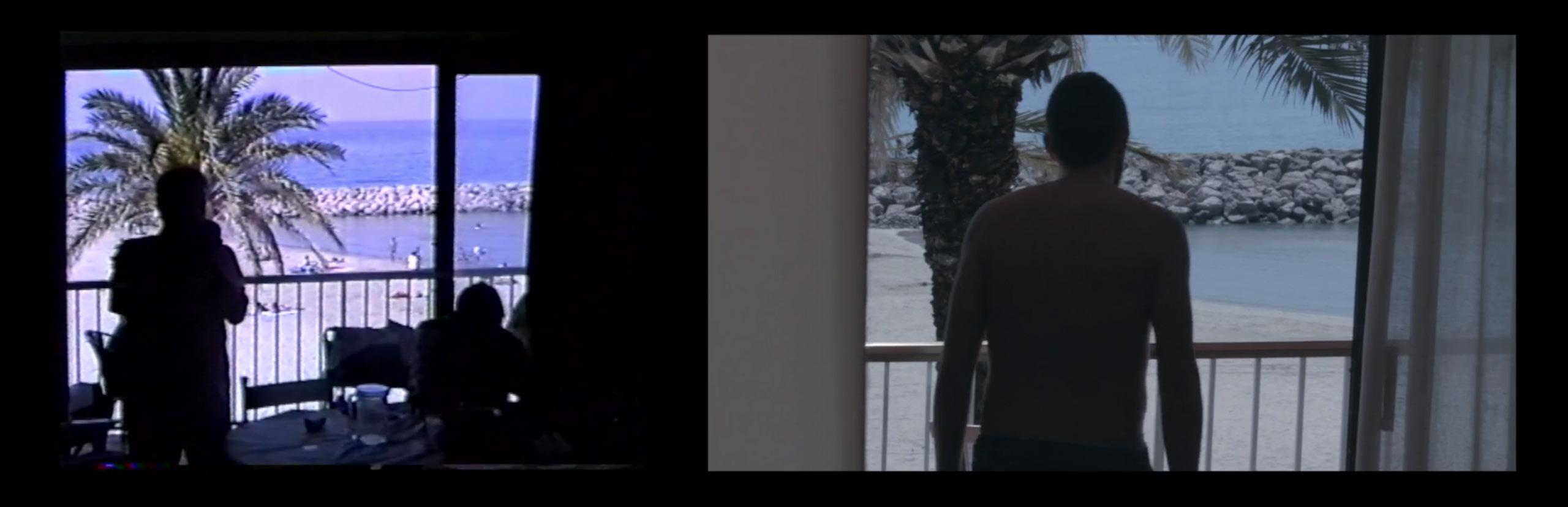

In the first shot, my father, the cameraman, zooms out and finds himself in a mirror, shadowed. In the second shot, my mother looks at the sea and I, still a baby, sit next to her. In the third shot, my mother is reading on a terrace, and I am also sitting there. In the end, my father zooms in at me and I look at the camera. Now, to move on, I need to go back.

In 2011, when I was studying cinema in Barcelona, I made a short film called El Retorn (The Return). It has always meant a lot to me since it was the one time that I worked in a different way. Usually, I would pick up a political issue and develop a story around it. I used to test different cinematic approaches for such a purpose, but the message remained the same: different versions of David against Goliath. But with El Retorn it was completely different. Something burned in me and I had to get it out.

I did not know how, so I moved in the dark. I wrote a very simple script, with no dialogues, and it resulted in a melancholic film echoing Antonioni’s Trilogia dell’incomunicabilità. It was not easy to explain it in words but I liked what the film conveyed. I felt I had worked honestly, whatever that meant, and I could re-watch the film time after time. So, imagine my surprise when I found the similarities between the three shots described above and three other shots from El Retorn. The characters from El Retorn seem to behave just like my mother reading a book or looking at the sea and my father hiding in the shadow, only visible through the mirror.

For me it was not just a matter of coincidence. I wondered what my gaze was. Maybe I was simply repeating someone else’s gaze, namely my father’s? The question transcended the making of El Retorn. No doubt I had inherited my political approach from him, so maybe also in the other projects I had done I was simply repeating an approach that was not mine? Was it my gaze? Was it my politics? A feeling of repetition and determinism arose.

Some insights are to be drawn from this experience. When I made El Retorn, I let my unconscious take the lead. Prior to the encounter with the images that my father had filmed 25 years earlier, watching the film was a return in itself. It worked as a melancholic balm that would calm some of my anxieties of a given moment. That is how melancholy itself works; the eternal return to some unfathomable lost harmony, the acknowledgement of which produces Victor Hugo’s “la bonheur d’être triste”.

At the same time, that unconscious way of working allowed me to reach a very neat image of an obstructed drive: the impulse to go back, to reconnect with a lost past. However, it is the conscious reflection upon it, six years later, which gave the 21 hours’ exercise the possibility to become movement and initiate a change. In other words, while El Retorn was the longing for an impossible return, contrasting it with the shots filmed by my father allowed me to start breaking the eternal repetition of my habits.

Lastly, I wonder what would have happened if I had watched the 21 hours of home videos spread over a month, instead of in one go. My suspicion is that I would not have recognised the similarities between the shots of my father and the ones in my short film. Because they belong to different tapes, I probably would have watched them on different days and would not have connected them. I would have watched, and thus seen differently. I believe it was the gesture of being almost one full day in front of my old me, which created an opening that allowed me to see these images from that perspective.

In other words, it was an experience that “no human being should have” that allowed mw to start breaking the predictable, the repetition.

PROJECT: DREAMS FOR A BETTER PAST

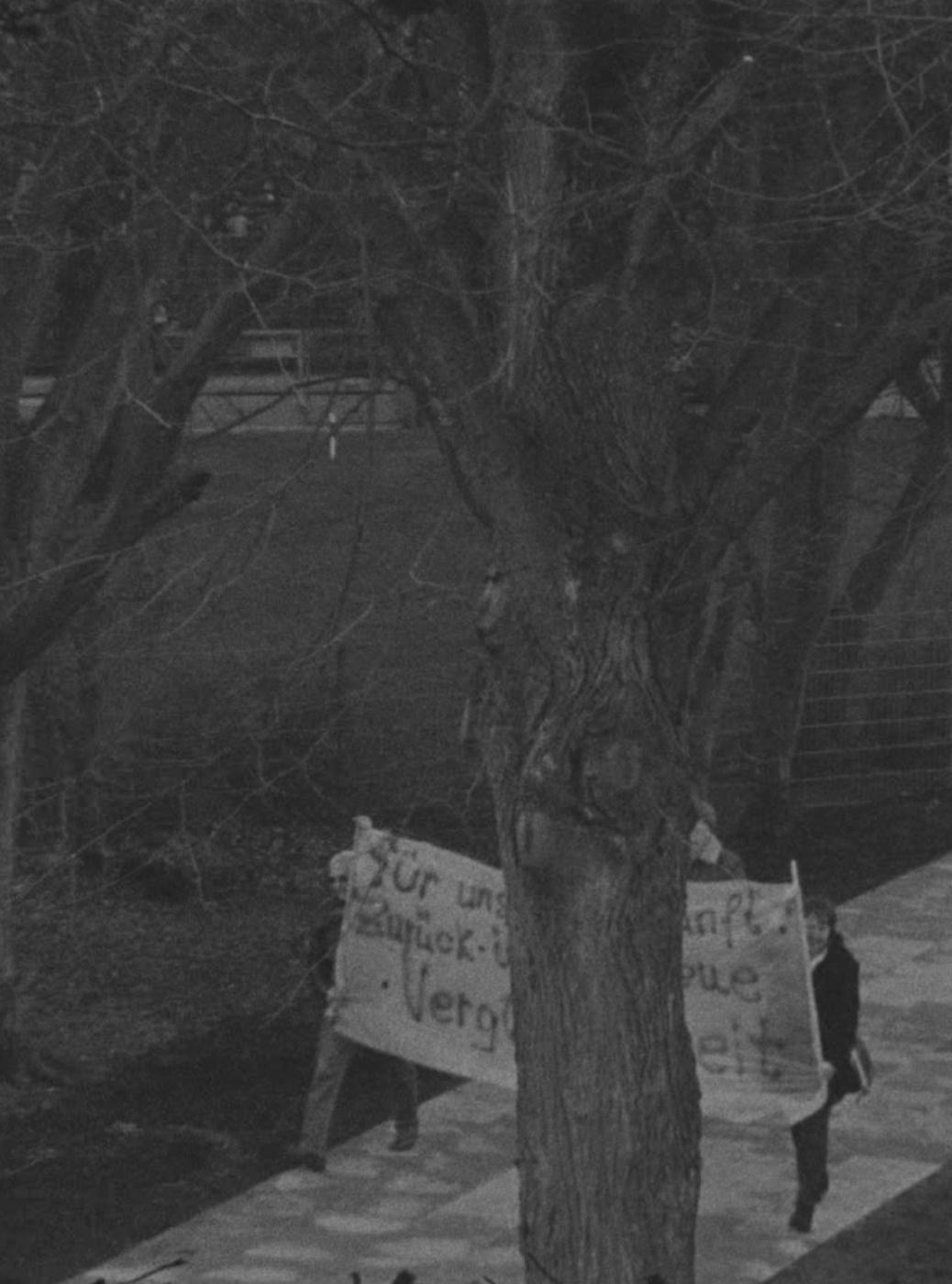

I find a picture of my father when he was a baby in the hands of his parents, they are smiling. It’s March 1944 and my grandfather is wearing an SS officer suit. The image feels like an original sin. I wonder what the relation is between this image and my father’s political activism during the 70s in Berlin. Furthermore, I wonder how this past echoes with me today, and with my relation to the world of images.

The information is limited and my father’s memory leaves room for improvement. So I try to approach the past by asking my father to read out loud, in front of the camera, some of the letters that my grandmother wrote to my grandfather when he was in prison after World War II. My father plays along for a while.

But then he gets tired of it, stops and says: “I am on strike. This is a neverending story”.

Faced with an ungraspable past, I take this no, this wall, this impasse, as an opportunity to imagine, speculate and create my own understanding of what (could have) happened. Reenacting old dynamics in front of the camera is an intervention which allows me to access that past. But a question emerges: how far (in time) do I want to go?

Dreams For A Better Past inscribes itself in the frame of films revisiting May 68 to check how that period resonates today. In The Intense Now (Salles, 2017), for example, the revolt is seen as a moment of synchronicity between personal and political will. And in A German Youth (Périot, 2015), the German students are portrayed as part of a generation whose political subjectivity is determined by the coming of age realization of their parents’ crimes.

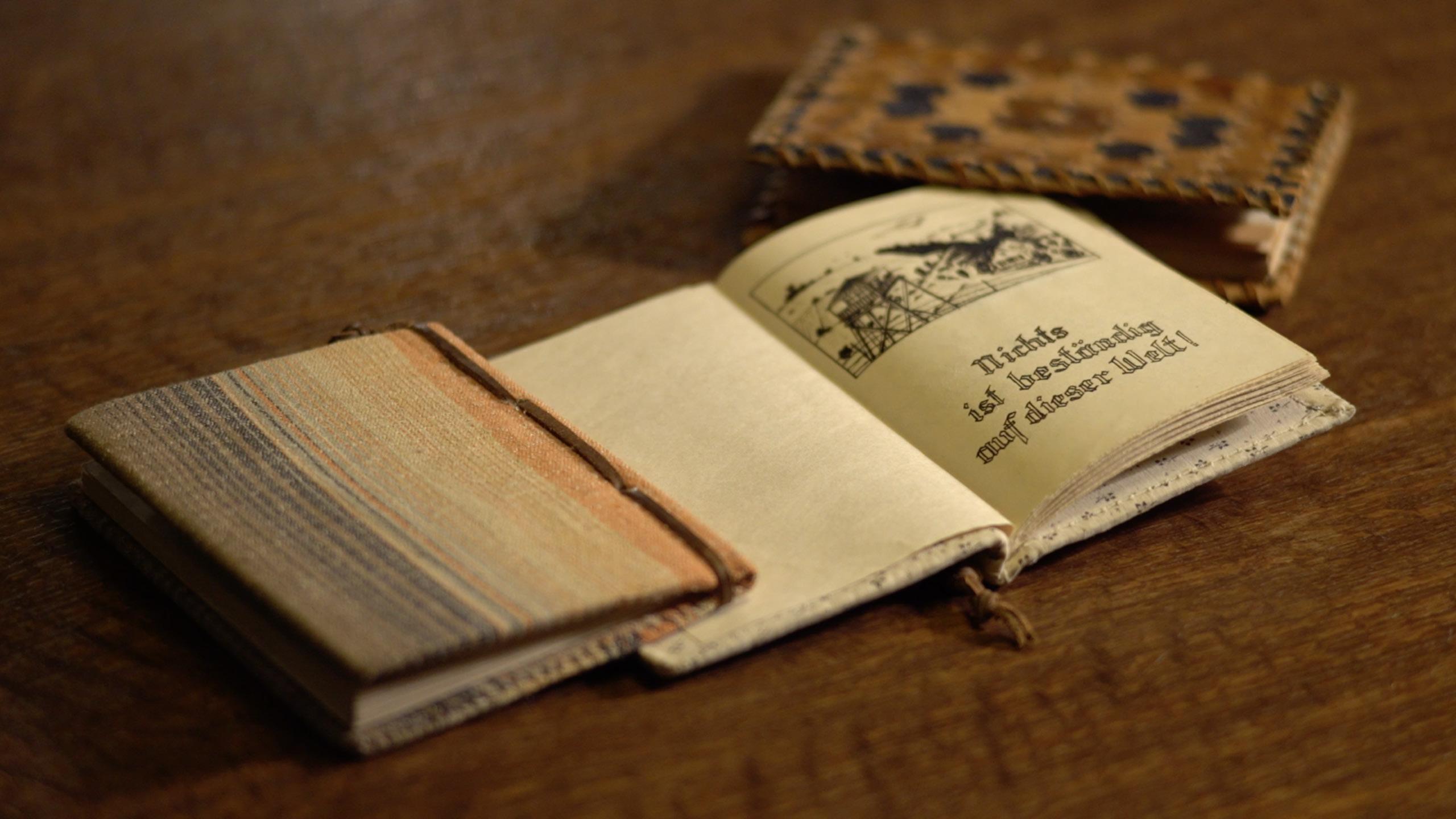

How to approach May 68 without falling into nostalgic idealisation and how to consider one’s subjectivity beyond a reactive logic, are the themes of Dreams For A Better Past. The core question of the perception of time affects both themes. While the usual experience of time as a horizontal phenomenon - as a linear succession of events - pushes us to feel nostalgia for the past and explain our actions as a consequence of previous episodes, vertical time - as a merging of past, present and future - opens the space for (re-) creating our own understanding of what happened and thus possibly having a different presence in the present.

Cinematic editing and reenactments are wonderful tools to deal with vertical time, blurring past and present. By intervening in the home videos that my father filmed in the 90s, when my grandfather was still alive, and by staging scenes for which I do not have any images I will appropriate May 68 from my perspective, from my subjectivity.

Script and direction Albert Kuhn Editing Diana Toucedo