17 minute read

SWEET CHARITY

Creativity was simply not an aspiration for the very first pupils of LEH, back in the eighteenth century. But even so, their sweet singing stole the hearts of all of those who heard it, paving the way for the freedom to express themselves and the rich imagination enjoyed by pupils today, reveals LEH archivist Elizabeth Hossain.

Anyone, who visits LEH today or reads about it through Holles Connect, will know that creativity thrives at LEH in the twentieth-first century. There are wonderful displays of artwork from students along the corridors, exciting and impressive music making in concerts and carol services and who, of those present, for the performances of ‘Chicago’ which inaugurated the opening of the Jane Ross theatre will ever forget the exuberance and professionalism of all who contributed to that production.

Girls today have a myriad of opportunities to display imagination and originality. They do so at school, and many choose careers in creative areas or enjoy choirs, amateur dramatics or art in their leisure time.

The early days

The situation was quite different when the school was first established in Redcross Street, Cripplegate. Creativity was not an aspiration the patrons and trustees of the ‘Lady Holles’ Charity School’ had for its pupils.

In 1710 the emphasis was on girls learning their catechism, followed by learning to read. Once the girls could read ‘competently well’, they were to be taught to knit stockings and gloves, to sew and mend, to spin and, finally, perhaps to write. Learning to write was at the discretion of the Trustees and, in the eighteenth century, only a few were chosen to be taught writing. The aim of the school was that the 50 poor girls who attended would know their place in society, be good members of the Church of England and earn their living as domestic servants.

A far cry from the plethora of opportunities and resources students at LEH have today to use their imagination and ideas to express themselves in writing, art, design, drama and music!

However, even in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries charity schools in the London area became known for their singing. On June 1st, 1710, just after the Lady Holles’ Charity school opened, the first 50 girls took part in the annual procession of charity children to St. Sepulchre’s Church in Giltspur Street to celebrate the setting up of charity schools. The girls were part of almost 3,000 charity school children attending the service which ended with a specially written hymn sung by all the children in unison. The Lady Holles’ girls then returned to school for a celebratory dinner.

These are the words of the hymn sung in 1710.

A Hymn for Any School

On this auspicious happy day, What incense shall we bring? What grateful humble homage pay To an Almighty King? Be his dread name on earth confessed, As ’tis by those above! What is th’ employment of the bless’d, But songs of praise and love? That breath from heaven we did receive, We thus in hymns restore; And while we on his bounty live, We’ll wonder and adore. Rescued from want, and vice and shame, We’ll all our future days Our great Creator’s love proclaim, And live but to his praise. May heart, and voice, and life combine, His goodness to express; May all that hear us with us join, And our Redeemer bless.

Source: An Account of Charity Schools …, 9th edn. (London: Joseph Downing, 1710), 61; and issued separately as A Hymn to be Sung at the Anniversary Meeting of the Charity Schools (London: Joseph Downing, 1710).

From 1782, as the numbers attending had grown so large, the service was held in St Paul’s Cathedral and the massed singing of the students began to attract a wider audience. Girls were prepared with extra coaching for months before given by the church organist of St Giles’ Cripplegate. Some idea of the spectacle can be seen in this engraving - on the right - from 1842.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the meeting of the charity children had become a huge and moving public occasion, reported regularly in The Times. The singing had an emotional impact on those who heard it. After his visit to the service in June 1791, Joseph Haydn wrote in his ‘London Notebook’, ‘No music ever moved me so deeply in my whole life’. In 1851, after hearing the charity children in St Paul’s, Hector Berlioz wrote to his sister that, ‘I have never seen or heard anything as moving in its immense grandeur than this gathering of poor children singing, arranged in a colossal amphitheatre’. It is reported that he was so impressed with the impact of the chorus of 6,500 children that he added a part for children’s voices in his ‘Te Deum’.

Hackney years

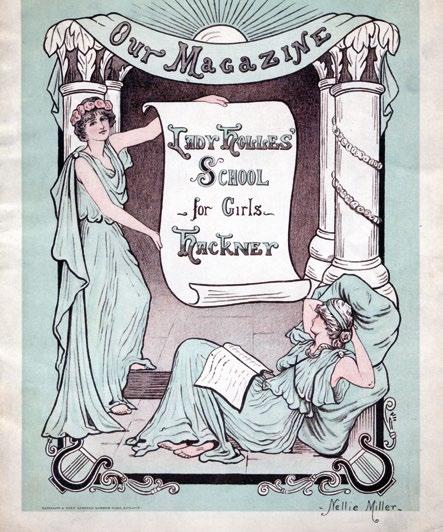

Aspirations for pupils changed in 1878 when the Lady Holles’ Middle School was set up in Mare Street, Hackney for the education of middle-class girls. Drawing and vocal music were on the curriculum and individual piano instruction was available as an extra. However, it is not until 1902, when the Hackney School became part of a national system of secondary education, that we have real evidence of greater creativity from the school magazine which was started in 1902. The original cover design for the magazine, shown here, was the result of a competition amongst pupils.

‘Our magazine’, the school magazine from 1902 until the start of the First World War in 1914, shows the enthusiasm of many pupils for creative writing and poetry. From 1906 the school had a dedicated Art Studio and the annual prize giving, usually in December, was always followed by a concert. In December 1905, the concert began with a piano duet and several solos, then a recital, ‘The Death of Sydney Carton’ from Dickens’ ‘A Tale of Two Cities’, and ended with the performance of an operetta, ‘Princess Zara’.

Margaret Bartlett, who regularly wrote fairy type stories for the magazine, went on as an ex-pupil to write a children’s play, ‘The Fairy Twin Sister’, with songs and music by Gilbert Carpenter. The play tells the story of the joys and sorrows of Mary Meadows and her fairy twin sister. Scenes are set partly in the woods and partly at Dame Crochett’s school. In the early years

Art Studio at Mare Street

of the twentieth century, before the outbreak of war in 1914 pupils regularly referred to themselves as ‘Holly fairies’ with Miss Clarke (Head Mistress) as Queen and to the school as ‘Hollyland’. We may smile at this innocent world today but can surely identify with the sense of community and participation it encouraged. societies were amongst the first. Despite war time conditions, the societies got off to a good start. By 1941 the Art club had grown to 100 members and was holding fortnightly competitions. The Literary Society had put on two plays and the Music Club had given three concerts including one given by Iris Loveridge, a former pupil who was a concert pianist.

The Fairy Queen, centre stage, with the help of elves and fairies putting all to rights for Mary and her fairy twin sister.

Dame Crochett’s School

Unfortunately, school magazine production ceased with the onset of war in 1914 and was not begun again until 1935 so we have few examples of creative work from these years. But, from interviews with staff and pupils from Hackney, we know creative work continued, both at school and in the ‘Holly Club’, the society for ex-pupils.

Move to Hampton.

There was some disruption when the school moved to Hampton in 1936. The need to focus on making best use of the temporary accommodation in ‘Summerfield’ and then setting up the school, attracting pupils and moving into the new building on the Hanworth Road site in 1937 took priority. But, at the end of the Spring term 1939, Nora Nickalls, the Head Mistress who had co-ordinated the move from Hackney to Hampton, judged the school was on a sound enough footing for clubs to be started and Art, Literary and Music

Iris Loveridge The tradition of an annual school play, usually produced at the end of the summer term, was also started in this post war era. Margery Duce, appointed Senior English teacher in 1947, played a key role in producing plays such as Lady Precious Stream (1951), The Rivals (1953), Murder in the Cathedral (1956), The Romanticks (1957) and The Servant of Two Masters (1959).

Encouraged by successive Head Mistresses at Hampton, these modest beginnings provided the foundations for Art, Music and Drama to take the more central place in the curriculum which they do today.

Elizabeth Hossain

An orchestra took longer to take shape but, by summer 1948, seemed to be gaining in expertise as it was noted in the December 1948 magazine, ‘The School is usually rather unkind in its comment on the orchestra, but this time the School must admit that, even to the most sensitive ear, they gave a very pleasant performance’. PS - Backdrops for these plays in the 1950s were provided by the Art department. We’d love to hear from anyone who took part in any of these plays from the 1950s, either on or backstage, with their reminiscences.

At the end of the summer term 1947, the first school drama competition was held. This had been initiated by the girls and organised by ‘an enthusiastic member of the LVI’. This proved so popular that it set the pattern for a drama competition organised by the Sixth Form which gave all students the chance to take part and which was often judged by an outside adjudicator.

We’d also love to hear from players from other productions to help us build up the archive.

Creativity Is the Secret Sauce in STEM

The essence of being creative is the ability to generate ideas, look at things with a fresh eye, examine problems with an open mind, make connections and use imagination to explore new possibilities. All essential ingredients when you’re studying Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths, reveals LEH STEM Co-ordinator Andy Brittain.

Every day I take the bus to work, past Michael Faraday’s grace-and-favour residence, Mason House, just round the corner from LEH near Hampton Court. It was awarded to Michael Faraday in the mid-19th century by Queen Victoria for a life-time’s devotion to science.

Queen Victoria was a passionate patron of the sciences. She believed wholeheartedly that Britain’s role as a great nation depended on its scientific advances and intelligent use of emerging technology. She acknowledged the true meaning of technology: the “science of art”. At LEH we extend this to the science of “artistry”. Creatives are welcomed into STEM with open arms: take these tools and build something new.

We form an understanding of our world through the relationships we form in our mind: our schema. The frameworks we construct start off basic: I release something, it falls to

Students with samples of moon rock the ground. They become more subtle: I release a feather, it gently drifts to the ground. They accommodate significant variations: I release a helium balloon, it rises. After a while we feel confident that our models are sufficiently nuanced to enable accurate predictions to be made.

In our idle moments we reflect upon what could be. Are there behavioural categories of motion? What common features do these objects share? Could we prevent things falling to the ground or rising to the sky? Does initial altitude matter? Does it matter over which patch of ground we drop things? Do they fall at the same rate? Do they glide, or plummet? Do they bounce or shatter? Do they tumble or remain stable? Does their temperature change?

Questions are the birth of creative thought. We can choose to be neglectful parents and let our progeny dissolve into the aether or we can search for new ways to articulate, represent, and communicate our ideas: we can synthesise solutions. This approach is found to a greater of lesser extent in every subject. However, in STEM it finds a uniquely productive form of expression, as revealed by the extraordinary achievements of LEH students - even during a pandemic.

Just as we became aware of the murmuring approach of viral hoards, moon rocks landed at LEH - on loan from the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC). Youthful imaginations burned like a thousand suns. Questions, hypotheses and investigations pushed beyond mere display case observations into the realm of poetry, art and experiment.

Students of photography acquired images and conducted real time examinations of the macro and microscopic. Observing texture, density, morphology! We scrutinized the visible and uncovered the invisible. Some of our artists painted planetary landscapes, while physicists employed magnetometers to map ethereal influences. All appreciated the scientific narrative: accumulated information, proffered alternatives, gathered data and communicated findings. Unconfined application of mind!

LEH is a member of the Institute for Research in Schools (IRIS). At the online IRIS Student Conference, two of our research groups discussed the interaction of leaves with

Moon Rock Landscape by Lauren in U6D

nuclear emissions. They proposed this investigation themselves and exposed their samples to alpha, beta and gamma radiation. Carefully controlled conditions did not limit their imagination in the slightest – it was channelled, like a tidal bore!

Some variables were fixed and others adjusted. Desktop technology and bespoke software identified and processed data. Collective knowledge and understanding secured conclusions. Observation and selective combination produced originality. To reinterpret Cicero: freedom is our power to do what we please, as long as we are not prevented by natural laws. Very well done to several members of our Sixth Form, who all submitted video presentations.

Creativity and innovation cannot be judged by one standard. Students that reach new heights before being formally handed the tools, deserve our admiration and recognition. When Sophie and Heidi, both in U4, first explored the Bifilar Pendulum they had no idea what this mechanical system was. They researched, they studied, they innovated. This is authentic learning. They recorded their data over several weeks, compiled their report, completed their analysis, and submitted a video summary. They secured a CREST award for this work, but their objective was to make an original discovery. The structure of the study might have already been well established – but they were not aware of that. They forged their own path. They created something new.

Collaborative endeavours present new and exciting challenges. Administrative and communicative issues need to be considered. Technology can provide the means, and our students are very good at finding new ways to transfer information, but it doesn’t configure the content.

LEH researchers, Zeta, Eleanor, and Sadie, presented their investigation using sonified data to study magnetic undulations in space at Queen Mary University’s “CosmicCon” virtual conference. This was in collaboration with representatives from Reach Academy and Grey Court school. The selection of appropriate data, means of display and expression all fell to the creativity of the students. High levels of oracy facilitated careful use of descriptions and phrases to best convey the meaning of the study. Innovation and combination demands careful reflection - as was shown in each submission to the STEM/Geography/English poetry competition. Who would have expected a student to write a poem entirely in binary code? Again we see rules channelling creativity.

We also stretched our “thespianic” muscles in the cross year-group rehearsals of Durrenmatt’s “The Physicists”, and the Thirds STEM/ Drama adaptation of Dr Who: “Nikola Tesla’s Night of Terror”. The musical musings of Mr Ashe, Composer in Residence, adapted atmospheric signals to more appropriate acoustics. This achievement reached the magical manuscript milestone – with a pending public performance.

Creativity extends beyond the direct product of one’s endeavours – great though that product might be. In the U4 Sophie, Heidi, Prakriti, Saanvi and Clemmie made up our Design Award winning BIEA team, calling themselves “Fanatical about Physics”, and representing LEH in a global webinar (with speakers from the US, Barbados and Malaysia) on bringing STEM designs to market. Our pupils consistently expand the horizon of collaborative exploits. We continue to find new combinations: within year groups, between schools, in partnership with higher education and with industry professionals.

Sophie and Heidi in U4 exploring the Bifilar Pendulum

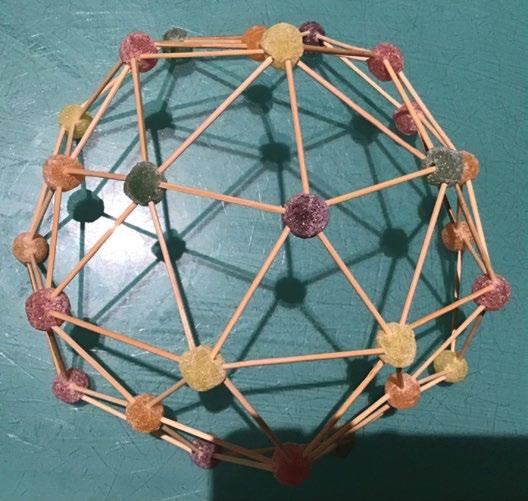

Serena, in the Thirds, was inspired by the James Dyson Foundation Geodesic domes construction project to build her own dome

Recognizing the value of collaborations – Heidi, Prakriti and Sophie, were founding researchers in a project funded by the Royal Society’s Partnership Scheme. This project has a long-term remit to monitor the environment with sensors built by LEH students using the resources and talent of the DT department and skilled science technicians.

Components were ordered from companies all over the world. When they arrived, we faced the challenge of soldering delicate circuitry. Our girls carefully followed the guidelines set by Kings College London, who have been providing advice and support throughout the process.

Again, during lockdown, pupils in L5 Lina, Anna, Mathumita, and Sunny won Bronze in the International Astronomy and Astrophysics Competition. “Attack on ZombieCats” presented their concept of a space sleep schedule system at the NASA International Space Apps Competition. L5 student Catherine also developed an app that supported people suffering with dementia. Among the many accolades her invention accrued was a prestigious Gold CREST Award, with a certificate signed by Professor Alice Roberts. Catherine went on to have her work listed by the British Science Association as one of the most creative scientific projects undertaken this year by a student. Oxford recognized her talent too, by awarding her first prize in their Physics Schools Poster Competition.

Indeed, LEH’s work with the BIEA is gaining such renown that L5 pupils Catherine, Avni and Wenyue were interviewed by the China Global Television Network, achieving international recognition from the broadcast.

The success and overall engagement of our students was applauded in a school STEM assembly, a webinar interview given by this correspondent to the British Science Association, and an article in the Times Educational Supplement.

The extent to which our STEM pupils reach out to the wider world cannot be overstated. A record number of the LEH community won medals in the British Physics Olympiad’s Junior Challenge last year. While Ella received a Platinum Award for participation in the Isaac Physics programme run by Cambridge University and Polina has pitched for the prestigious Arkwright Engineering Scholarship.

Serena, in the Thirds, noticed the James Dyson Foundation Geodesic domes construction project – which combines artistic aptitude with technical know how – and built her own dome!

The production line of innovative ideas continues to rumble on: The first LEH STEM Fair mooted and advanced by Polina and Phoebe in U5P, during the early days of the pandemic has gained some traction. Amazing video investigations were submitted- and three virtual speakers agreed to participate in the event: Professor Heather Jarman (Consultant Nurse), Geraldine Cox (Imperial University’s Artist in Residence) and Marlo Garnsworthy (US Science Communicator).

Both our incumbent L6 STEM Scholar, Arabella and our incoming STEM Scholar, Isabelle, U5, contributed inspirational videos to the Fair. Arabella has advanced her own initiatives by issuing regular STEM newsletters and assembling an elite squad of eco diversity warriors in the Thirds to take part in the BP Ultimate STEM Challenge.

It is exactly these qualities of passion, imagination and creative thinking, which as you can see, extend right across the school, that are key if we are to fit our pupils for the challenges that lie ahead – be they future pandemics, climate crisis or automation in the workplace. For all our sakes, creativity in every subject, but perhaps most especially STEM, needs to be a priority.