7 minute read

A beginner’s guide to the art of anchoring. by Felicia Schneiderhan

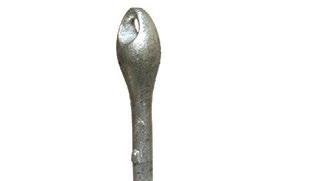

POPULAR ANCHORS FOR THE GREAT LAKES

MOST POPULAR

Boats 21’ to 50’

DELTA: Holds well in most bottoms. Struggles in rock.

MUSHROOM: Good for permanent moorings and soft bottoms. Good for permanent moorings and soft

BRUCE/CLAW: Holds well in most bottoms.

Struggles in clay/hard mud.

MOST POPULAR

Boats under 21’

DANFORTH/ FLUKE: Holds well in mud/ sand. Lightweight. Struggles outside mud/ sand.

STRONGEST

ROCNA/SPADE: Highest holding power but expensive.

PLOW/CQR: Responsive to wind/ tide changes.

Good for a wide variety of bottoms.

GRAPNEL: Good for river anchoring. Not ideal for longterm anchoring.

Wind

HOW TO ANCHOR

WHAT’S ON THE FLOOR? SAND is one of the best bottoms for anchoring. It’s good for setting a strong anchor, for all kinds of anchors. Best styles for sand are Danforth and fl uke anchors. We consistently have good luck with a Bruce.

MUD needs anchors with a larger fl uke area and wider shank-fl uke angle, which enable the anchor to set deeper where the mud has greater shear strength. And since mud often lies over another material, an anchor that can dig deeper into the next fl oor layer will hold stronger. Fluke anchors are recommended.

ROCK depends more on where you drop the anchor than on the anchor type. Grapnel and plow anchors — like the Bruce, CQR and Delta — have a strong structural strength and work best.

CLAY, SHALE and GRASS are the hardest bottoms to anchor in. The anchor’s weight is more important than design for digging deep and holding. Delta and CQR are known for piercing plant life, but be careful that the underwater garden doesn’t give you a false setting.

Boat in reverse Anchor digging in

power. In her book “Superior Way,” boating expert Bonnie Dahl recommends keeping a third anchor onboard, as the floors of many lovely anchorages can be riddled with rock or debris just waiting to steal your anchor. And, Dahl points out, make sure to have at least two different types of anchors onboard for the variety of situations that can arise (see sidebar on p. 43).

A SIMPLE START Let’s start with a basic anchoring in calm water with a sandy bottom. There are a few things to do before you slowly loosen that windlass or toss the anchor. First, check the weather — especially the wind direction. Are you staying overnight? Make sure to find out if the wind is predicted to shift. Falling asleep on a hook in calm water is lovely — until you wake up in the middle of the night to find the wind has shifted and you’re rolling like crazy. Select the harbor you anchor in based on wind direction for the length of your stay.

As you approach the harbor, watch where other boats are anchored. Which direction are they pointing? Are they all over the place or turned into the wind? This will give you a good sense of the wind direction and where to position your vessel. Note the water depth, watch the charts for how quickly the depth changes, and know the draft of your boat. With one anchor, your boat will likely move in a radius around the anchor, so make sure you have a wide enough radius so you won’t hit the bottom or another boat.

How far from another boat should you be? “Far enough that I don’t hear them talking,” Mark says.

Make sure the windlass is working before dropping anchor; it’s a pain to realize too late that you have to haul up an anchor by hand. Clear the area on deck; you don’t want anything — or anyone — getting caught in the anchor chain as it’s going down. Our kids love watching the anchor go down, but they know to stand a few feet back. This moment requires extra attention, as a windlass is one of the more dangerous pieces of equipment onboard. Make sure there is nothing behind your boat (like a Zodiac raft). It’s best if one person deploys the anchor and someone at the helm maneuvers the boat and watches for trouble.

You’ll need to let out a fair length of chain, called the “scope;” about five to seven times the length of the bowsprit to the seafloor is a good rule of thumb (see graphic above). So if the depth of the water is 7 feet, for example, and it’s 3 more feet from the water surface to the bowsprit where the anchor rests, it’s advisable to deploy 70 feet of chain.

Once the anchor hits the floor, shift into a slow

SCOPE GUIDE

Short Stay 5:1 Overnight 8:1 Heavy Weather 10:1

DEPTH: 10’ 50’ 80’ 100’

reverse; this will set the anchor. Until it’s set, your boat is not secure and will drift.

At some point you’ll sense tension on the chain. Shift to idle, and the boat will swing so that the bow points into the wind. You can feel the sense of being caught.

Once your anchor is set, take precautions to make sure it stays set. A GPS or chartplotter with an anchor alarm will alert you if the boat swings too far from its original position. You may have to adjust it so the alarm is not ringing in the middle of the night when there’s not really a problem. Your depth sounder can also alert you if the depth changes considerably. And then there’s simply paying attention. If you start to drift, or if another nearby boat inches too close, it’s time to haul up the anchor and give it another go.

When it’s time to raise the anchor, start the boat and motor towards the anchor’s location as you

WHAT’S THE SCOPE? Scope is defi ned as the ratio of the length of an anchor rode from the bit to the anchor shackle and the depth of the water under the bow of the boat measured from deck height. According to BoatUS, scope calculations must be based on the vertical distance from the sea bottom to the bow chock or roller where the anchor rode comes aboard. Most anchor manufacturers recommend that a scope of 7:1 ensures the anchor’s holding power. When in doubt, more scope is better than less. And then there’s the practical side: While a 7:1 scope is ideal, a crowded cove can inspire boaters to go with 3:1 or 4:1 scope. In these scenarios, you can securely set the anchor, and then shorten the scope as needed.

begin raising the anchor. The momentum of the boat moving forward assists the windlass in getting your hook onboard.

TRICKIER SITUATIONS Of course, waves are not always calm, the floor is not always sandy, and the harbor is not always spacious. There are a variety of more extreme anchoring scenarios to practice and prep for. For example, deploying two anchors will better secure your boat. In a small anchorage where you need to restrict the boat’s natural wandering, you can set one anchor close to shore and a second anchor in the other direction. You can also set two anchors off the bow, which will reduce the arc of movement but still lets the anchors hold even if the wind shifts and the boat pulls against them.

And then there’s the greedy floor that won’t give you back your anchor. We encountered this at Devil’s Island in the Apostles, when the rocky bottom snagged our Bruce anchor. Pulling at an angle would only lodge it deeper, so Mark’s solution was to maneuver the boat directly on top of the anchor and let the waves lifting and lowering the bow naturally jimmy the anchor loose. The lake didn’t win... that time.

Anchoring is an art, and developing your nautical intuition takes time and practice. But when you’re swinging on a secure hook, surrounded by water, there’s nothing better. ★