7 minute read

Roger Fenton

Photography Pioneer Roger Fenton

By Margaret Brecknell

Advertisement

The son of a wealthy Lancashire businessman, Roger Fenton is regarded as one of the key figures in the early history of photography, even though his career as a photographer lasted little more than a decade.

Roger Fenton was born at the family home of Crimble Hall, near Rochdale, on 28th March 1819. As well as his business interests, Fenton’s father, John, was also Rochdale’s first MP.

After graduating from the University of London in 1840, Fenton Junior looked set to pursue a career in the law. However, his real passion in life was art.

In the early 1840s, he travelled to Paris to pursue his artistic ambitions. Here, he met some of the leading French artists of the day including Paul Delaroche. It may well have been Delaroche who introduced Fenton to the then strange new concept of photography. The French artist is famous today for allegedly exclaiming, “From today, painting is dead” after seeing a photograph for the first time in 1839. Yet, in fact, he was an enthusiastic early advocate of photography, who, in a report to the French Government, commented that the “process completely satisfies all the demands of art”.

Subsequently Fenton returned home to London and continued his art studies, but, in 1851, he took the momentous decision to give up painting and focus on photography. He is said to have made the decision after seeing a display of photographs on a visit to the Great Exhibition, held that year in London. He held his first exhibition the following year, including scenes of the capital and portraits of family and friends.

In August 1852, Fenton was invited by the civil engineer, Charles Vignoles, to photograph the construction of a suspension bridge across the Dnieper River near Kviv. Now the capital of Ukraine, Kyiv was at that time in the Russian Empire. Fenton took the opportunity to travel extensively round the whole country and photograph some of its most iconic landmarks such as the Kremlin in Moscow.

These photographic images of previously unseen exotic locations caused quite a stir upon Fenton’s return to London in late November and brought his work to the attention of some very influential people. He began an association with the British Museum and was charged with taking pictures of its important artefacts. A special photographic studio was constructed on the Museum’s roof, which remained in use for well over a century until it was demolished during the 1990s.

In 1854, Fenton was asked by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert to take photographs of the British royal family. His first photos of the Queen were relatively informal in composition. This indicates that they were not intended for public display, but rather for private use by the royal family. The royal couple were known to be early photography enthusiasts and supported Fenton in his work.

In early 1855, Fenton set off on a mission to document events in the bloody conflict between the British Empire and its allies and the Russian Empire, which was then taking place on the Crimean Peninsula. He travelled with official letters of introduction to top-ranking British officers from Prince Albert. His trip was financed by a Manchester publishing firm called Thomas Agnew & Sons, who were hoping to publish his images.

However, it seems Fenton also had the backing of the British Government. British forces in the Crimea had already suffered heavy casualties and the war was becoming increasingly unpopular with the public back home. Fenton appears to have been given the brief of presenting the conflict in a positive light and to avoid any graphic images of the wounded and the dead.

Fenton travelled to the Crimea accompanied by his assistant, Marcus Sparling and a servant called

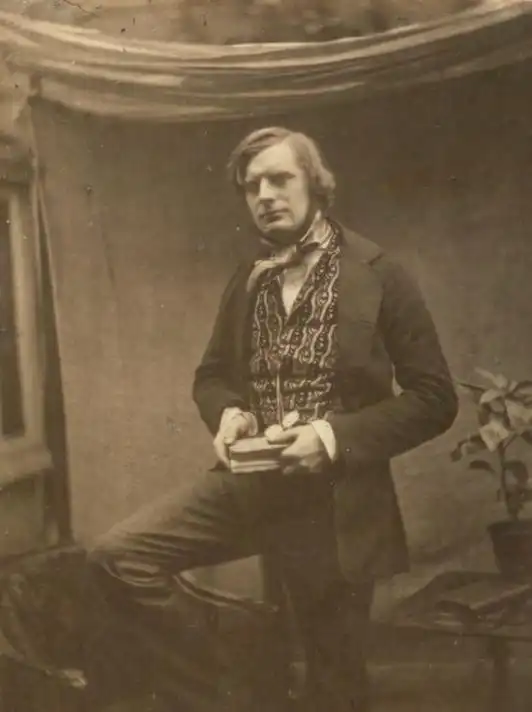

Roger Fenton 1852 Self-Portrait

Officers of the 4th Light Dragoons during Crimean War Photograph by Roger Fenton

William. He also carried with him a huge amount of photographic equipment. One of Fenton’s photographs is of Sparling seated at the front of the specially converted large horse-drawn photographic van, which was used to transport this equipment and also served as a mobile darkroom.

Fenton’s connections in high places allowed him unprecedented access to the British military campaign, but several factors meant it became impractical to take shots of the action on the battlefield. Conditions were far from ideal, with the light and heat making the process of photography and development difficult. In addition, although Fenton’s “photographic van” was a necessity, it made him conspicuous to the enemy and was fired on by Russian forces on more than one occasion.

Nevertheless, the photographer took some 350 images of the conflict during a four-month stay in the Crimea, thereby providing the first extensive documentary picture gallery of a war. He took pictures of the top army officers and scenes in camp. His most memorable images, though, were the scenes picturing the aftermath of battle. Fenton’s most famous war photograph, entitled Valley of the Shadow of Death, was taken in April 1855. The image captures the desolate landscape in which the war was waged, littered with cannon balls from the conflict. His photographs were published in newspapers of the day and thus brought images of war to the general public in a way that had never been done before.

Fenton returned home in late June after contracting cholera and over the following months an exhibition of prints from the conflict toured the country. He was summoned to Osborne House, the royal family’s summer residence on the Isle of Wight, to give Queen Victoria a personal account of his experiences in the Crimea. The story goes that because of his illness the Queen permitted him to lie on a couch during the audience. He also travelled to Paris to show his prints personally to Emperor Napoleon III. The Crimean War finally ended early the following year.

For the remainder of the decade, Fenton travelled all over the UK, taking pictures of the architecture and landscapes of his native land. He photographed the royal residences of Windsor and Balmoral Castles. He visited many of the country’s most impressive cathedrals, such as Salisbury, Lichfield and Lincoln, and ruined abbeys like Fountains, Rievaulx and Lindisfarne. Fenton also returned to his native Lancashire to take pictures of the countryside surrounding the River Ribble and views of the River Hodder in the picturesque Forest of Bowland, as well as striking photographs of Stonyhurst College.

Fenton also continued to experiment with new techniques and themes. In 1858, he produced a series of portraits in his studio on an Oriental theme, possibly inspired by his travels across Russia and the Crimea. Two years later, he experimented with still-life images of fruits and flowers in what appears a deliberate attempt to reproduce in photography the kind of still-life portraits more traditionally seen in the oil paintings of artists.

Domes of Churches in the Kremlin Moscow Photograph by Roger Fenton

Shadow of The Valley of Death Photograph by Roger Fenton

This work was very well received, but, in 1862, to the surprise of nearly everyone, Fenton suddenly abandoned photography. He sold all his equipment and resigned from the Photographic Society, of which he had been a founding member. Instead, he decided to pursue a career in the law.

Various reasons have been suggested for this sudden change of direction. Back home in Lancashire, the family’s cotton manufacturing business was suffering serious financial problems as a result of the cotton famine in the early 1860s. Fenton may well have decided to return to the law belatedly, as it provided a more secure financial future for his wife and children.

Other sources claim that Fenton was unhappy with the direction in which photography was heading. He viewed it as an artistic endeavour. However, in the 1862 International Exhibition, held in London, photography was not placed in the fine arts section, but rather, for the first time, in the section containing machinery and scientific instruments. Photography was now considered a trade rather than an art form.

By the time that Fenton passed away, aged 50, in August 1869, his death only merited a passing mention in the newspapers. It seems that his role as one of the pioneering figures in photography was already then being forgotten. Yet, through his work he showed the many ways in which this then relatively recent invention could be used to portray subjects that had previously been the sole domain of the fine artist.