7 minute read

Post-COVID-19: a bio urban future

Michael Cowdy is a Director and Studio Leader for McGregor Coxall based in the Bristol and London studio

Fraser Halliday is a Senior Landscape Architect working for McGregor Coxall in the Sydney studio

Until only recently, the sudden and radical transformation of our daily routines seemed unfathomable. Many of the protective measures introduced in lockdowns globally have challenged the very essence of urban lifestyles, planning, governance, conservation and management.

And while we can only speculate upon the longlasting repercussions sweeping our social, economic and political spheres, we can anticipate that like many pandemics before, COVID-19 presents an opportunity to accelerate progressive changes to cities’ open space models, as well as stimulate investment into the conservation of our wild areas.

The former is required to address the weakness in our physical and social infrastructure exposed during lock down, whereas the latter is essential to prevent further habitat destruction and the multibillion-dollar international wildlife trade, which, according to the WWF, is the cause of emerging zoonotic infectious diseases. And more worryingly, since February this year, environmental agencies have reported an uptake in deforestation as well as increases in poaching, animal trafficking and illegal mining worldwide, the consequences of opportunists expanding their activities and taking advantage of diminished forest monitoring and government presence.

Therefore, it is critical to recognise that conservation and city planning are absolutely interlinked. The challenge we face is ensuring governments and local authorities embrace a fast paced, bold planning approach that rethinks the open space model, one which applies a more holistic and systematic blue and green infrastructure framework. Cities need to transform from a static planning system to a more adaptable model which is performance and target based.

Low Carbon Ballast Point Park.

© McGregor Coxall

Recognising that cities need disruptive, smart solutions to tackle shared global challenges, McGregor Coxall established the Biocity Research Studio in 2006. Combining science with technology and design, it conducts research via global partnerships with universities, industry, private investors, NGO’s and government. A key initiative arising from the research is the Bio Urbanism platform. Developed as a largescale open source systems-based planning framework, it seeks to foster regenerative relationships between cities and the biological systems upon which they depend. Utilising advanced GIS technology and data modelling, the platform reviews ten systems – five urban and five bio – to measure the environmental performance of cities against targets and global best practice indicators. The bio indicators rate factors such as carbon, biomass and ecological health, and the urban indicators rate factors such as infrastructure, thermal comfort, urban form, density and energy flows. To achieve urban prosperity, Bio Urbanism maintains that any major planning decision should create favorable outcomes across all ten systems.

Sustainable framework for a new city district in the Middle East.

© McGregor Coxall

In the Middle East, we are currently planning a city which spans multiple ecological zones and geographic conditions, encompassing environmentally significant habitats and cultural heritage sites within a largely undeveloped but heavily debilitated landscape. The ambitious blueprint recognises that progressive cities must become early adopters of strategies that promote low carbon living through fossil fuel divestment, thus enhancing economic competitiveness and climate resilience in the digital age.

The regional plans create frameworks where people, planning, policy, and technology work together to foster innovation and address critical questions of environmental stewardship, social equity, and sustainable economic growth. Crucial to this is shifting from a linear economy where we ‘Take-make-waste’ and move to a circular economy, where waste either falls into the biological process or remains in circulation as part of the technical process. Adopting this bold framework has resulted in significant development of a Bio Urbanism circular economy framework. The latest thinking is that the ten systems work together to produce minimum drawdown on natural capital. This will prevent damage to habitats, vegetation, hydrology and soils, and assist in stabilising regional ecology, while living systems integrated into urban design will enhance climate and infrastructure resilience.

During the pandemic, the value of nature has been heightened as people have re-established a relationship with local parks, rivers and wildlife. Our natural systems are crucial to increasing the urban environment’s resilience to climate change, whilst also performing well documented biophilic benefits. In recent years, our work in China has been focused on China’s Sponge Cities program, where flood mitigation through natural-based solutions is viewed as critical.

Lingang Bird Airport and Eco Park.

© McGregor Coxall

This is also demonstrated on Lingang Bird Airport and Eco Park, where an 80-hectare industrial wasteland was recreated into a wetland habitat located along a key bird migration route known as the East Asian Australasian Flyway (EAAF). The ecological design consisted of the creation of a series of habitats designed to support the specific needs of more than fifty species of birds in three different water habitats. The habitat strategy was supported by a comprehensive water management strategy, using treated wastewater as a source for the wetlands.

This environmentally focused project also played a crucial social role for the living and visiting community by providing an attractive and engaging natural space. Access to adequate multifunctional open space has become vital during the lockdown and placed a lens on the importance the public realm plays in supporting physical health and mental wellbeing. The challenge is ensuring a post-COVID world learns from its past mistakes and invests in quality open space that is accessible and connected.

Creating an Interconnected Blue Green Network with Transport for London.

© McGregor Coxall

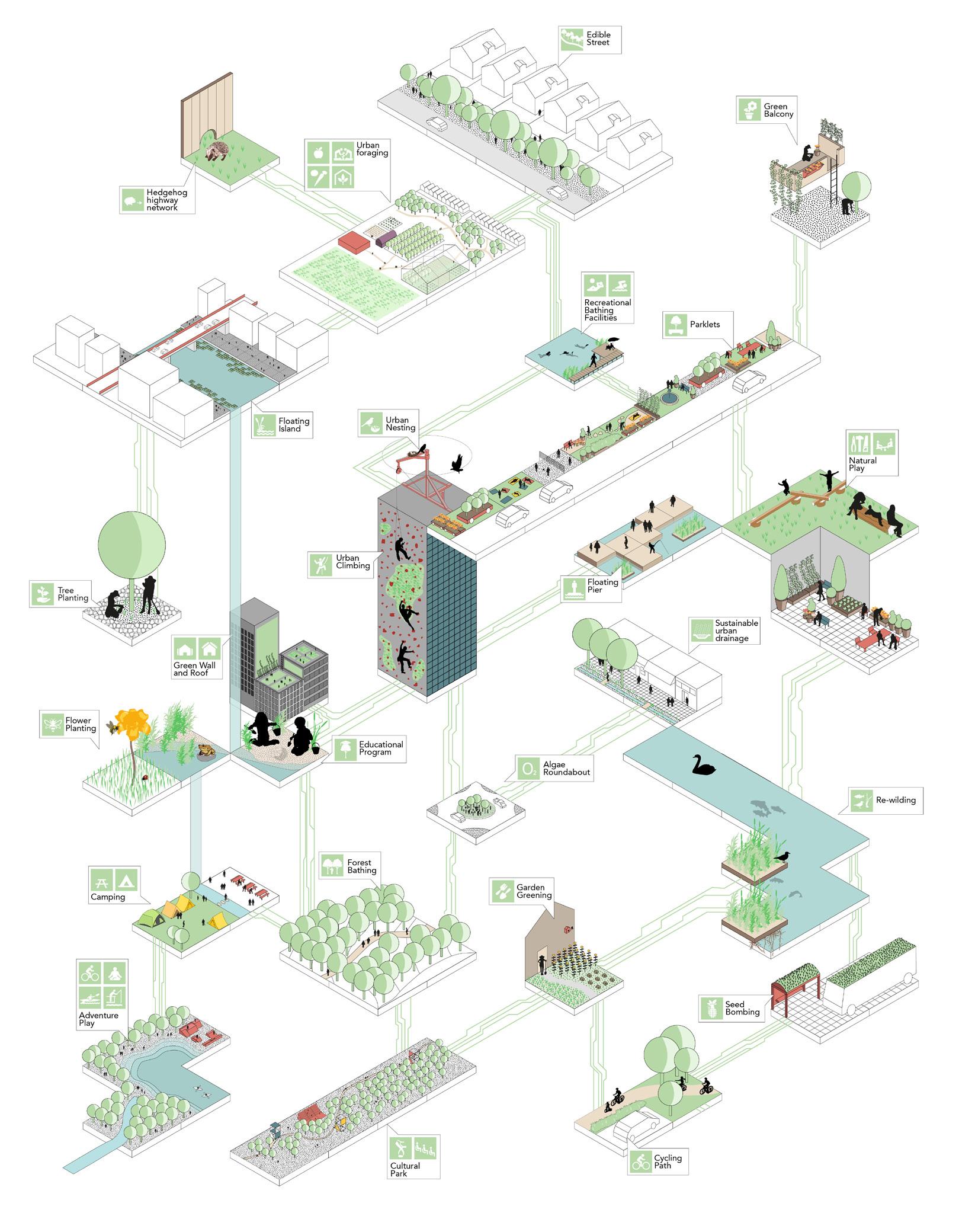

Our ongoing work with Transport for London aims to address inequity across the city by establishing key performance metrics to 2,500 hectares of TfL’s development sites. It looks at ensuring all sites are held accountable for their social, environmental and economic performance through a Sustainable Development Framework, which adopts ‘Triple Bottom Line’ thinking. In particular, we’ve been providing Green and Blue Infrastructure strategies and Healthy Street Checks to identify targeted initiatives that promote active transport choices, active lifestyle, biodiversity net gain and increased urban greening.

High streets around the UK are facing unprecedented challenges due to changing economics, the environmental impact of climate change and the social inadequacies of our public realm, which have been exposed by COVID-19. However, what the pandemic has done is reveal our high streets as community centres and reconnected people to the importance of the shopkeeper. A recent high street renewal project we’ve completed is in Maitland, Australia, where a declining centre with a 50% vacancy rate is now a thriving place with a purpose. The project looked to reposition Maitland as a leisure-based retail centre supported by an experiential night-time economy of local produce & Hunter Valley wine. The design was focused on a new ‘shared zone’ and River Link building that established a connection between the high street and Hunter River. Planned with embedded flexibility for future change, the high street embraces smart technologies enabled through free Wi-Fi and programmable LED lighting. This allows the entire street mood to be instantly changed to support the new calendar of events and festivals.

Maitland High Street and River Link Building.

© McGregor Coxall

With demands on our public realm changing, technology offers a solution to support the creation of flexible and adaptable spaces. Embedding technology into our public realm enables us to monitor user demands to intelligently inform decision making and create vibrant, engaging spaces. In the City of London, our smart street concepts employ digital surface treatments and modular furniture systems that allow spaces to adaptively respond to users’ demands. This multifunctional technological street creates engaging public spaces that facilitate social interaction, healthy living, community connection and cultural expression to curate public life.

Cheapside and Bank Junction Smart Carpet.

© McGregor Coxall

The value of quality public realm and space needs to be prioritised so that adequate budgets are identified. Both the public and private sector need to adequately invest in the spaces they create and manage, as they are proven to enhance a place’s social, environmental and economic performance. A collaborative approach between local authorities, stakeholders and communities will ensure greater understanding of the importance of Blue Green Infrastructure, ownership of the strategy, and commitment to delivery of its intended outcomes.

Measuring, monitoring and reporting of policy outcomes and delivered priority actions is essential. All best practice examples of Blue and Green Infrastructure have embedded a process of reviewing its successes and failures. Don’t fear failure – embrace it, learn from it, and implement better solutions. The path to prevention of future pandemics lies in a holistic approach to city planning, conservation and managing resources across the globe. Decision makers globally need to be aware of these dynamics moving forward, as they begin to think about investing and managing resources in the future to kickstart the economy again.