11 minute read

How food can save the world

By Carolyn Steel

Carolyn Steel is a leading thinker on food and cities. Her 2008 book Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives is an international best-seller, and her concept of sitopia (food-place) has gained broad recognition across a range of fields in academia, industry and the arts. A director of Kilburn Nightingale Architects in London, Carolyn studied at Cambridge University, and has since been a visiting lecturer at Cambridge, London Metropolitan and Wageningen Universities, and at the London School of Economics, where she was the inaugural Studio Director of the Cities Programme. A Rome scholar in 1995-6, Carolyn is in international demand as a speaker, and her 2009 TED talk has received more than one million views. Her second book, Sitopia: How Food Can Save the World, was published by Chatto & Windus in March 2020.

Carolyn Steel argues that putting food at the heart of our thinking represents our best chance of creating an equitable, healthy and resilient society.

How will we live in the future? More specifically, how can we thrive on our overcrowded, overheating planet?

By 2050, 80 percent of us are expected to be living in cities. But what will those cities look like, and what effect will they have on their productive hinterlands, and the natural world in which both sit? The current pandemic has thrown such questions into high relief, raising fundamental issues concerning our relationship with nature, the urban-rural partnership, and our very idea of “a good life”. And at the centre of all these questions is one that often gets overlooked: that of how we are going to eat.

Living in a modern city like London, it can be hard to see how profoundly food shapes our lives. Industrialisation has obscured the vital links without which no city could survive: those linking it to the countryside. The empty supermarket shelves that greeted shoppers at the start of lockdown were thus a wake-up call for many: the moment when the illusion of effortless plenty was shattered. For ecologists, of course, this was far from news as many had been warning for decades that our increasing encroachment on wilderness and loss of biodiversity was exposing us to a number of threats, such as climate change, mass extinction and zoonotic disease.

The crisis we now face is the result of a 12,000-yearold experiment in eating and living. The invention of farming and subsequent rise of urbanity around 5,500 years ago represented a radical shift in the way our ancestors lived. For the previous two-million-or-so years, humans had been hunter-gatherers, living in small numbers in a variety of habitats: plains, forests, mountains, deserts, sea coasts and arctic wastes. Our ancestors’ ability to thrive for millennia in such diverse environments is testimony both to our human flexibility as omnivores and our inventive use of technology to help us survive. Aboriginal Australians’ modification of their landscape through practices such as the strategic burning of forest dates back a remarkable 50,000 years (1) . The success of such forager societies bears witness to our human capacity to live in harmony with the natural world.

So when did we lose the knack? The short answer is that our advancing technological capacity has blinded us to the need to maintain such a balance. This was not the case for our ancestors: on the contrary, early city-dwellers were quick to recognise both the promise and danger of their new way of life. Most creation myths conflated the discovery of grain with the birth of civilisation, while simultaneously viewing the activity that produced it as a curse (2). When our ancestors took up farming, not only did they work harder than before, but their health suffered: average heights and life expectancies shrank, as people began suffering from previously unknown diseases of malnutrition such as rickets, scurvy and anaemia (3). By swapping their rich natural diets for the relative poverty of domesticated foods, our ancestors started down a path with which we are now all too familiar. Today, we know that complex, diverse diets are fundamental to plant and animal health, yet we remain locked into a system bent on producing the very opposite.

COVID-19 has served to highlight what was already clear to anyone who cared to look: our relationship with nature is dangerously out of kilter. If we are to maintain our current lifestyle to the end of the century and beyond, we’ll need a very different strategy for living and eating – activities so inextricably linked that they effectively form one indivisible whole. Whether or not we realise it, we live in a world shaped by food, a place I call sitopia (from the Greek sitos, food + topos, place). Since we don’t value food, however, we live in a bad one; so bad, indeed, that it threatens our destruction. In rethinking our lives and their relationship with the natural world, therefore, there is no better place to start than food.

Urban Paradox

Since food was highly valued in the pre-industrial world, it provides us with plenty of clues as to how we might re-adopt a similar attitude. Both Plato and Aristotle, for example, saw self-sufficiency as the ultimate aim of the polis (state), since this was considered key to its political independence. Both philosophers described an ideal state as one in which every citizen would have a house in the city and a farm in the countryside from which to supply it. Household management, or oikonomia (from oikos, household + nemein, management) was thus the building-block of the state, in contrast to chrematistike, the making of money for its own sake, which Aristotle condemned on the basis that it had no natural limits and thus could never bring happiness – a warning that modern economics (derived, of course, from oikonomia) seems to have forgotten.

Roman food miles. The Food Supply of Ancient Rome.

© Carolyn Steel

Ambrogio Lorenzetti: Allegory of the Effects of Good Government – A rare moment of city and country in harmony.

© Bridgeman Images

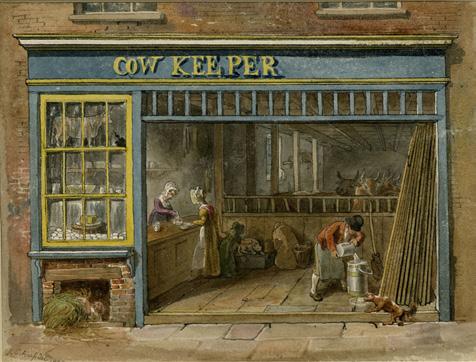

Most pre-industrial cities did in fact practice some form of oikonomia, since most had highly productive local food economies. Towns and cities of every size were invariably surrounded by market gardens, vineyards and orchards, where fruit and vegetables could most benefit from ‘night soil’ (human and animal waste) that was carefully collected and rotted down for manure. Most households also kept pigs, chickens or goats, feeding them on kitchen scraps. Since cows and sheep could walk, they were often reared far from the city, and were fattened up on spent brewers’ grain before being finally brought to market. Since fresh meat was a luxury that few could afford, most city dwellers survived on bread, rice or some other staple, with a little dried meat or fish, cheese, pickles and vegetables for flavour. Menus in the pre-industrial cities were simple, and due to the difficulty of feeding themselves, most cities remained small.

With occasional exceptions such as ancient Rome (which used its military might and a vast slave-driven navy to import most of its food from its conquered territories), this urban model survived intact until the coming of the railways. The ability to transport food rapidly and cheaply over great distances effectively emancipated cities from geography, and they soon began to spread, in tandem with their hinterlands. Within a decade of the railroads’ arrival in the American Midwest, most of its native animal and human inhabitants (an estimated 60 million bison and Native American tribes including the Niitsitapi (Blackfeet), Sioux, and Chippewa) had either been slaughtered or removed to reservations, and its grasslands converted into the largest expanse of grain the world had ever seen. Chicago became the food emporium of the world, its meatpackers growing rich on cheap grain fed to cattle. The packers were the original pioneers of the modern food industry, inventing many of the systems and processes – efficiencies of scale, streamlined production, logistical mastery and ruthless business practices – that would come to shape it. They laid the foundations that twentieth-century industrial farming would complete: the illusion of cheap food. As the countryside became increasingly mechanised, rationalised and drenched with chemicals, city dwellers basked in lower prices, while politicians turned a blind eye to the mergers and acquisitions that were creating the giant food corporations that bestride the globe today.

A cow-keeper in Drury Lane, London, 1825. Fresh milk in the pre-industrial city

© Trustees of the British Museum

Effects of Good Government

The question of how to eat in the twenty-first century is a ‘wicked’ problem, since it involves everything from ecology, politics and economics to culture, values and identity. In pursuit of the modernist dream, however, its importance has been systematically obscured. What is increasingly clear is that the way in which we feed ourselves can no longer be left to the vagaries of the market. After decades of conveniently ‘leaving it to Tesco’, our politicians must accept the responsibility that their ancestors always recognised as primary: feeding their people.

What does this mean in practice? Certainly not a return to the nationalisation of wartime, but rather a recognition that, since it is central to our chances of living well in the future, food must be central to our political thinking. By extension, so must the question of how we use and inhabit land. Five and a half millennia into our human urban experiment, nothing essential has changed. We still depend on nature for our sustenance, and our greatest collective responsibility is to maintain a balance between our needs and those of the natural world.

The invention of cheap meat. Chicago Union Stockyards, 1880.

As utopians have long recognised, this means achieving a balance between city and country. Perhaps the most famous image of this – Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s 1338 series of three frescoes, The Allegory of the Effects of Good Government – depicts the medieval city-state of Siena, its urban and rural halves in perfect, productive harmony. Its message is clear: look after your countryside, and it will look after you.

Growing food in the city. Ben Flanner, Brooklyn Grange Rooftop Farm.

© Carolyn Steel

The concept was reworked for the railway age by Ebenezer Howard in his 1902 plan for a Garden City. Recognising our human need both for society and nature, Howard argued that a network of dense communities of limited size (32,000 residents) surrounded by countryside could provide the benefits of city and country living, while negating the downsides of both (6). The Garden City was, in effect, a prototypical city-state, in which all land would be owned by the trust, so that when land values rose, it would be the citizens, not private landowners, who would benefit. Howard got his idea from US economist Henry George, who argued in his famous 1879 book Progress and Poverty that the land belonged to everyone, and those who wished to use it exclusively should pay for the privilege through a community land rent, or land value tax. Such a ground rent, Howard believed, could not only fund public services for the Garden City, but would preserve the agricultural land around it, which private owners might otherwise be tempted to develop.

One hundred years on, the time for such ideas has come. The evidence is overwhelming that we need to put the oikonomia back into economics: we must revalue land and its most essential product, food. We have entered a neogeographical age and can no longer afford industrial food’s externalities. Revaluing food would be a radical move yet would also be our most direct route towards rebalancing our relationship with nature. Industrial meat or palm oil gained at the expense of lost rainforest would become unaffordable, while locally produced organic vegetables would emerge as the bargain they have always been. Using food as a lens to rethink the ways we share and inhabit land could create new landscapes in which both humanity and nature can flourish. As Patrick Geddes once put it, we can make ‘the field gain on the street, not merely the street gain on the field’ (7). At every scale, from kitchen gardens and neighbourhood orchards to regional food networks, post-fitted metropolises and regenerative farming, we can bring society and nature closer together. Alongside the necessary land and tax reforms, we can build a world in which everyone can afford to eat and live well – surely the baseline for any great society.

COVID-19 has thrown up numerous unanswered questions, not least what the future urban-rural relationship will look like. Yet the pandemic has also shown that more regionally-based, less frenetic lifestyles are not only possible, but desirable for many. Could such findings form the basis of a new vision of what constitutes “a good life”? Nowhere is the question more acute than in the UK, where our imminent departure from the EU will bring massive disruption to all forms of trade, while our theoretical freedom to choose how we farm and eat in future will test our values as never before. Whatever the outcome, however, one thing is for sure: putting food at the heart of our thinking represents our best chance of creating an equitable, healthy and resilient society fit for the future.

References

1 See Bill Gammage, The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia, Allen & Unwin, 2012, p.xxii.

2 The Bible famously does this in the story of Adam and Eve.

3 See Tom Standage, An Edible History of Humanity, Atlantic Books, 2010, p.18.

4 E. F. Schumacher, Small is Beautiful, Vintage, 1973, p.81.

5 See Aristotle, The Politics, T.A. Sinclair (trans.), Penguin, 1981, p.85.

6 Ebenezer Howard, Garden Cities of To-Morrow, (1902), MIT Press Paperback Edition, 1965.

7 Patrick Geddes, Cities in Evolution (1915), Routledge 1997, p. 96.

Watch Carolyn Steel speaking at the LI CPD Day: Bringing nature into the city

https://campus.landscapeinstitute.org/video/opening-session-4-keynote/