8 minute read

Integrating the city and food systems: an Indian perspective

By Sandeep Balagangadharan Menon

Sandeep Balagangadharan Menon is a practising landscape architect and a core faculty member at KRVIA, Mumbai. His academic interests range from ecological urbanism, landscape ecology, sustainable urban water management, ecological corridors and wetland systems.

Availability of food has been one of the primal considerations to help a species decide on its habitat – including humans. This explains the location of some of the earliest civilisations near fertile river valleys.

Producing food is a complex process which depends on seasons, biogeographic qualities of the land and the intertwined issues of economic gains and socio-cultural histories of food-producing societies.

The advancements made in the last century in storage and transportation have made it easy for food produced in distant lands to be made available in the local super markets within days, with an assurance of enhanced shelf life. This is a game-changer in ‘urbanperiurban-hinterland’ relationships, but it has also in effect alienated the perceived connections between the acts of producing food and the eventual consumer. This alienation, even though it is a global phenomenon, has distinct effects on the lives of urban dwellers, especially in the ‘Global South’, or less developed regions.

Indian cuisine is myriad and diverse. Local ingredients, traditional cooking techniques, bioclimatic peculiarities and cultural beliefs have traditionally led to a great diversity. It may be a bit naïve to imagine the ‘spicy curry’ as being the epitome of Indian cuisine, since in India the word ‘curry’ could connote a variety of dissimilar dishes with entirely different ingredients depending on the location within the country.

The role played by ’food’ in the history of the Indian sub-continent is very interesting. The European quest for controlling the ‘Asian Spice Trade’, especially of the Malabar black pepper, propelled the late 15th century Iberian expeditions of Christopher Columbus and Vasco Da Gama. Columbus’s expedition lead to the ‘discovery’ of the Caribbean islands in 1492. What followed was an exchange of plants, diseases and culture – often referred to as the ‘Columbian Exchange’. This expedition introduced tomatoes, chillies, potatoes, pineapples, cashews and many more plants to the “Old World”. Vasco da Gama’s voyage to India opened up new avenues for spice trade from the shores of the Malabar Coast to Europe, and also led to the introduction of many of the common ingredients which were unknown to the gastronomic palate of the region. The following centuries saw the introduction of many new species of plants which have since become an integral part of the Indian cuisine. Easily cultivable vegetables with longer shelf lives gained prominence over the native species, including potatoes, tomatoes, chillies and tapioca.

More than 820 million people globally do not have secure access to food (1). In an increasingly unequal world, the proportion of people who are “food insecure” is growing at an alarming rate, especially in cities in times when urban immigration has reached peak levels. (UN Habitat 2010).

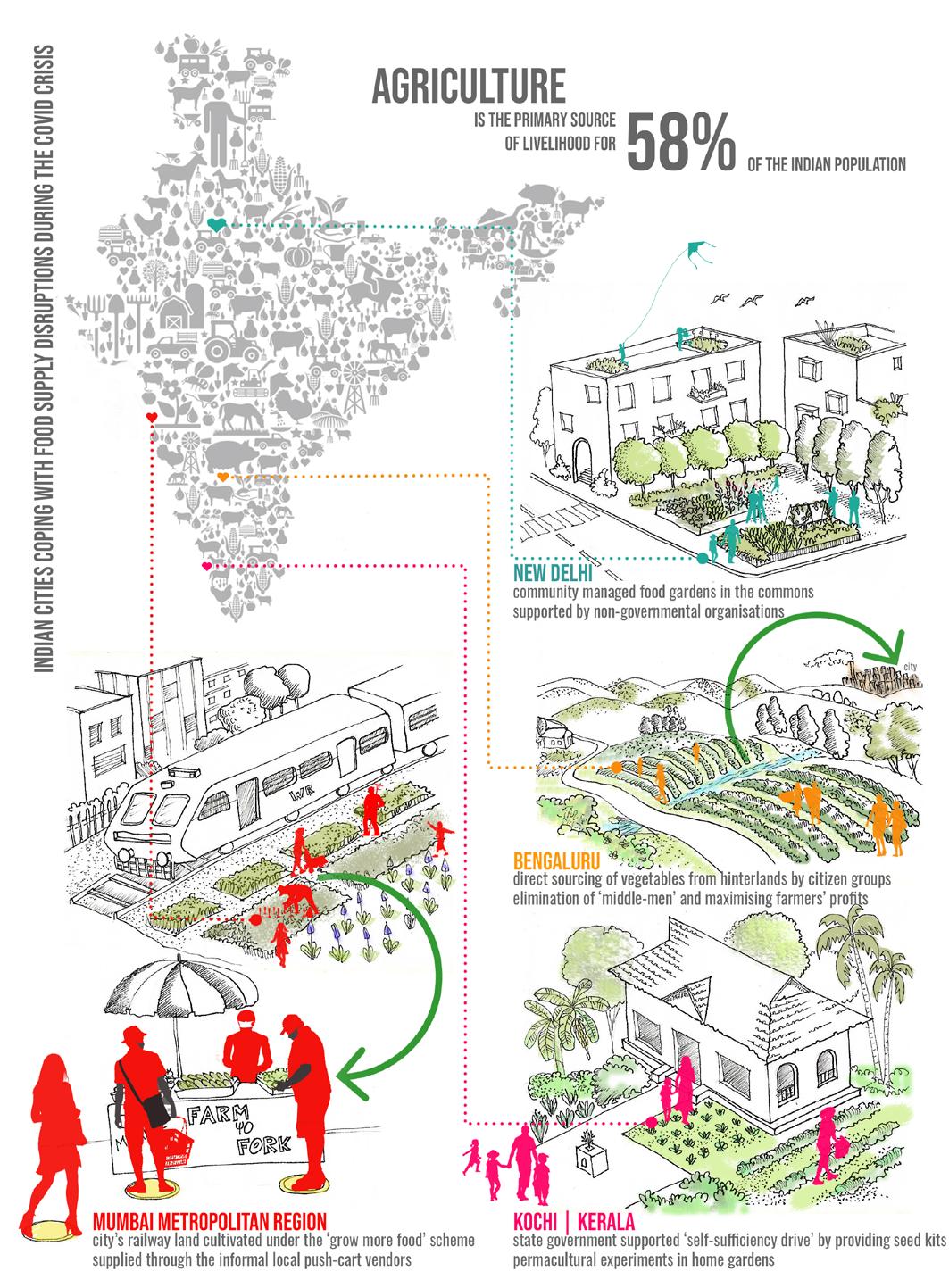

Agriculture is the primary source of livelihood for about 58% of India’s population, and India is among the 15 leading exporters of agricultural products globally (2). However, Indian cities have been witnessing an massive increase in their urban immigration rate coupled with climatic vagaries that destroy crops, leading to localised food crises. This is further complicated by the varying food cultures, cuisines of choice, and consumption patterns of the various cities within one country. The lockdowns imposed as part of the COVID-19 pandemic control measures led to an unprecedented disruption in the food system chains from rural zones to the urban areas. This has revealed a chasm in the urban systems of Indian cities, an implicit dependence on rural hinterlands for agricultural produce, and the lack of urban farms in cities.

Railway vegetable gardens

© Sandeep Balagangadharan Menon

Access to food is heavily compromised for the urban poor, primarily due to their low income levels and the rising costs of living in cities. The choice of food in such cases may be dictated by the lower costs of sourcing it, and not necessarily on its nutritive value, leading to malnourishment and severe deficiencies of micro- and macro- nutrients. Indian cities are marked by the presence of the ‘informal sector’, which also includes the informal food systems produced and consumed within cities. This sector is deemed invisible while planning for cities, and an unusual focus is often given to the act of ‘formalising the informal’ in the planning processes within the city.

A ride on the suburban system of trains in Mumbai would reveal another facet of this informal chain: the planted strips of coriander, spinach, okra and other leafy vegetables along the edges of the railway tracks throughout the city and its suburbs. This is an outcome of an innovative scheme by the Indian Railways titled ‘Grow More Food’, which prevented encroachment of the railway lands in the 1970s, wherein vacant railway land in the city of Mumbai and its suburbs were allotted to railway employees on lease for cultivation, and to help them earn extra income to support their families3. However, the lack of quality control in the system and high chances of contamination (due to the use of untreated sewage water for irrigation) are likely to put the health of consumers, mostly the urban poor, at severe risk. The informal sector of food supply is crucial in bridging the gap between the supply and access of food in the city. The planning and design for urban zones in the ‘Global South’ needs to take the informal sector into cognisance and allow for provisions to augment them.

The COVID-19 induced lockdown – and the subsequent mass exodus of migrant workers from Indian cities to the countryside – have exposed the inadequacies of the urban systems, especially the informal systems in the urban milieus. However, this time of crisis also spurred hope within individuals, organisations and some local Governments, who are taking food security and sufficiency seriously and rising to the challenge with some ingenious ideas.

Households in the coastal State of Kerala in peninsular India witnessed a renewed interest in cultivating food in one’s own yard. The State is well known for its dependence on food and raw materials from neighbouring States, despite having salubrious weather, fertile lands and abundant water resources. The lockdown imposed by the Government, combined with panic buying, led to scarcity of essential food and vegetable supplies. Government organisations like Vegetable and Fruit Promotion Council Keralam (VFPCK) and HortiCrop initiated a ‘food selfsufficiency drive’ by encouraging homestead farming. VFPCK launched the sale of ‘Vegetable Challenge Kits’ comprising of biomanure, organic pesticides, growbags and seeds priced at reasonable rates, encouraging a new crop of homestead enthusiasts to indulge in farming local varieties of vegetables suited to the climatic and dietary patterns of Kerala.

Local produce

© Sandeep Balagangadharan Menon

Megacities like Mumbai, Delhi and Bengaluru witnessed a new citizen-led movement of sourcing fresh produce directly from farms. These movements attempted to solve one of the biggest paradoxes of our modern food production systems: the marginalisation of the actual producers due to the heavy handedness of the middlemen, who siphon off a substantial share of the profit. The lockdown and interstate movement restrictions forced the established logistics and supply networks to cease to function. Multiple citizen groups in various parts of the cities got together, and arranged the supply of fresh produce directly from small scale farmers and food producers who were apprehensive of the lockdown and its subsequent consequences for their harvest. The recent push by the Indian Government to adopt digital payments at the grass roots has also helped farmers receive timely payments.

The pandemic also gave environmental activists and NGOs in cities an opportunity to push for more localised food systems. They also ensured that the negative impacts of large scale agriculture on biodiversity are being brought to the forefront of policy discussions. Many residents in group housing societies and high rise apartments came together to indulge in community farming in their balconies and terraces, using the seed kits provided by the NGOs. These NGOs and citizen groups have also been trying hard to fill in the voids in supply chains to the urban poor, and are augmenting the informal systems of distribution to the vulnerable in society.

The pandemic and the climate crisis do force us to question the greater challenges of long term support to these sustainable models of production and supply. This is an opportune moment for landscape architects and planners to integrate these models and tackle constraints concerning the changing climate and environmental issues. Innovations in how food production can be reimagined as an integral part of city living are the need of the hour. Homestead farm patches, terrace gardens and urban common gardens could be the key to offsetting at least part of the food demand for cities. The notion that food has nothing to do with urban landscape planning and design needs to be revisited. The ongoing Smart Cities programme of the Indian Government, which focuses on urban technological upgrade, spatial design enhancements and urban inserts, need to be reimagined and keep in mind the issue of food security to ensure a truly resilient urban future.

© Sandeep Balagangadharan Menon

References

1 ‘The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2019, ‘Safeguarding Against Economic Slowdowns and Downturns’. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO); Rome, Italy: 2019. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/ca5162en/ca5162en.pdf [accessed on 1 October 2020)].

2 https://www.ibef.org/industry/agriculture-india.aspx [accessed on 20-11-2020].