8 minute read

Home sweet home

Safeguarding the sense of place in new residential landscapes requires considerable commitment, argues Nicholas Miller.

A ‘sense of place’ embodies both personal experiences and emotional connections to surroundings that hold meaning for us. The legitimacy of this concept lies in its ability to prevent homogenised design.

For landscape architects to truly grasp the meaning of a sense of place, it is advantageous to set aside preconceptions derived from professional experience and education. Genuinely listening and empathising with the perspectives of those inhabiting the spaces affected by our work is crucial. As Geoffrey Jellicoe warned, ‘There should be no such thing as an international style, for the reduction of all design to a pattern would reduce us to the animal state.’

The transformation or creation of residential landscapes can bring numerous benefits to a neighbourhood. However, it can also pose challenges for residents, as they often hold cherished memories associated with the physical places that come under threat. Regeneration frequently raises concerns about the potential of disruption to existing communities and the loss of local identity. Therefore, change is often met with resistance.

I consider myself fortunate that the neighbourhood of my childhood home in Bolton, Lancashire (sic),1 has remained almost unchanged. Reliving fond memories in the suburban streets, woodlands, and fields of that environment brings me great comfort and happiness. As a result, I hold an almost spiritual connection to that place. Indeed, my subconscious mind often returns to that home in my dreams, despite having lived in several cities since.

While the character of satellite towns such as mine remains largely intact, central Manchester has undergone dramatic change. It has transformed into a vibrant and modern city through significant investment. As the latest wave of redevelopment has swept across the city, places where many families lived, including my own, have unavoidably changed. The Victorian streets where my mother grew up were deemed uninhabitable by modern standards and demolished, leaving behind a soulless grass verge in its place. Planning decisions such as this sever the connection between cherished childhood memories and the geographic location.

The singer Morrissey offered a very poignant perspective on the impacts of this as part of a BBC documentary. ‘The place where I grew up no longer exists, apart from in the local history library. Queen’s Square was a very strong community, and it was also quite happy, but there’s nothing of it now. It was like having one’s childhood wiped away, it has been completely erased from the face of the earth. I feel great anger, I feel massive sadness. It’s like a complete loss of childhood, because when I pass through here it’s completely foreign to me.’

In the professional sphere, one can become desensitised to the fundamental impacts our work can have on real lives, but perhaps drawing upon our own experiences can aid empathy.

My professional attentions shifted to London where I’ve lived and worked for the past decade, which has undergone even greater regenerative change. This transformation has revitalised existing residential areas and forged new ones, fostering vibrant communities across the city. While it has spurred economic growth in many previously deprived areas of the city, these changes have also significantly contributed to gentrification, disproportionately affecting lower-income demographic communities.

The place where I grew up no longer exists, apart from in the local history library. Queen’s Square was a very strong community, and it was also quite happy, but there’s nothing of it now. It was like having one’s childhood wiped away, it has been completely erased from the face of the earth.

London, with its rich histories and diverse cultures, traditionally embodies a strong sense of community and working-class solidarity. Local values typically include pride in identity, a history of trade and industry, and a welcoming attitude to newcomers. Over recent decades high-rise developments, often built on brownfield sites, have led to positive economic impacts and improvement in the quality of public space. However local people across the city have experienced significant challenges. The ability to remain living in central areas, or even in the wider city, has been challenged by spiralling house prices. Also, the dramatic rate of change often causes alarm, as communities struggle to maintain a connection with a rapidly evolving urban environment with familiar landscapes transforming beyond recognition.

Case Study - The Aylesbury Estate

The Aylesbury Estate is a large modernist social housing estate currently undergoing redevelopment in south London. It experienced many challenges since construction was completed almost 50 years ago, characterised by antisocial behaviour and high crime rates. The unwelcoming brutalist architecture and modernist site planning has often been blamed as part of the problem. Despite being impersonal and lacking human scale, there remain popular aspects to the place among residents who, despite hardships, have fostered a strong local community.

Residents acknowledge the unacceptable living conditions but have expressed a deep-seated fear of community breakup and relocation. Local pressure to repair rather than rebuild was fuelled by scepticism about the real drivers behind attempts to improve the area.

Redevelopment commenced a decade ago, with phased construction replacing the existing buildings with new housing and community spaces. The redevelopment aimed to address various issues, including concerns about the estate’s layout, safety, and the quality of living conditions for residents. In response to these challenges, HTA Design devised a new landscape-led masterplan. One of the founding principles was to reintroduce the safety of traditional streets, knowing this could encourage well-understood behaviours, due to the passive surveillance it fosters.

The remaining veteran trees became crucial markers, mapping the ghost of the Victorian street pattern and representing the last remnants of a long-forgotten place. Historical road names were reintroduced, and the proposed housing was laid out accordingly, rehousing every resident in new accommodation. The masterplan retains the modernist parkland trees also and is complemented by extensive new planting, which significantly increases the range of species. The look and feel of the new streets give a nod to the modernist estate through the carefully chosen hard landscape proportions. However, the spaces were softened to moderate the negative feelings often associated with developments of that period.

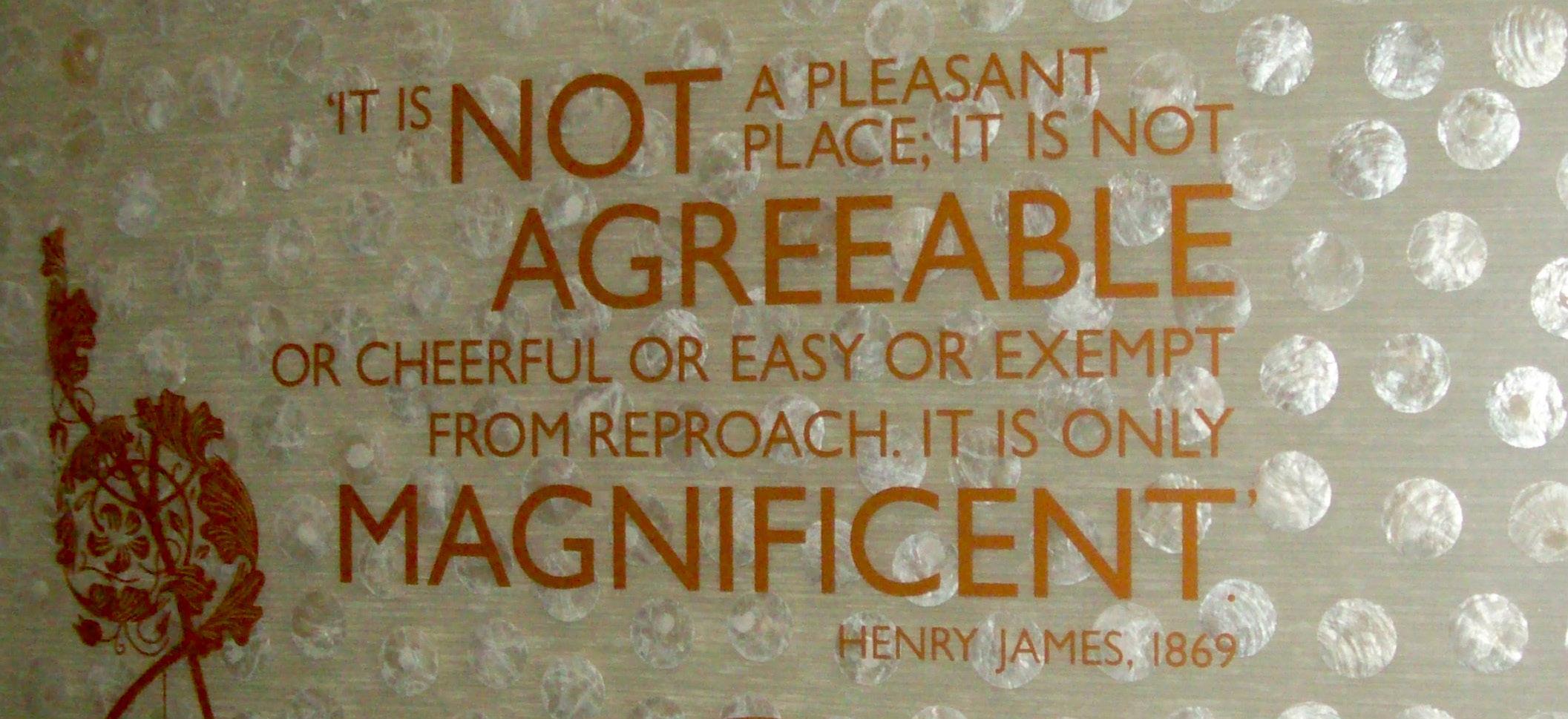

The initial phases of redevelopment included the creation of several new public spaces of various scales, which hosts a new library and healthcare centre. The array of squares, parks and gardens offers a variety of human scales and amenities, with comfort at the heart of the design. The first phase has been seen to be successful, evidenced when observing positive use and behaviours. The design of landscape spaces provides much needed comfort, however; as Time magazine argues in its essay ‘What Makes a City Great?’, comfort alone does not make a place great.

The project has achieved great success in a challenging context. As future phases progress, residents and community groups alike suggest that there appear to be opportunities to hone the placemaking strategy even further. Spaces could integrate features that celebrate the cultural and historical aspects of the estate, which resonate with the collective memory of the community. Greater consideration could be given to referencing character and materials of the site’s past incarnations. Planting design could be themed to reflect the diverse multicultural heritage of the community.

Valuable lessons could be drawn from the success of the neighbouring Burgess Park redevelopment. The BMX Park, for example, a source of several Olympic gold medals, has effectively taken on a nurturing role by making teenagers visible in positive, constructive ways. Various aspects of the park’s social infrastructure address the specific needs of the communities, such as outdoor cooking and sports facilities, which have proved very popular.

Safeguarding the sense of place in new residential landscapes requires the pre-existing community to remain at the heart of transformation. Addressing gentrification requires thoughtful planning, inclusive policies, and a genuine commitment to the wellbeing of all residents.

It is suggested therefore that the long-term success of new residential landscapes is contingent on our ability to:

– Celebrate local distinctiveness

– Develop informed site-specific landscape responses

– Ensure that the design is truly informed by community engagement

– Help decision makers, who are ideally reflective of the local community, understand the nuances of the place

– Retain and promote locally distinctive businesses

– Safeguard the local community by providing a range of affordable housing that meets the existing and future tenure required Safeguarding the sense of place is vital to the success of new residential landscapes. It can help to bridge generational gaps, foster community resilience, and ensure new chapters in the story of a place are informed by lessons of the past. We should endorse a deeper understanding of place as designers, recognising our projects not merely as ‘sites’ but as repositories of meaning, memories, culture, and identities. In the words of Jan Gehl, ‘First life, then spaces, then buildings: the other way around never works.’

Nicholas Miller is a Landscape Architect with 16 years’ experience of the design and delivery of residential environments and public realm. He is also a Visiting Lecturer at UEL.