Emerging technologies pose significant opportunities for the landscape sector to grow, thrive and contribute its expertise. It is incumbent on all of us to engage and seize this opportunity together.

Rob Hughes CEO, Landscape Institute

Find out more on page 64

In today’s world, it can be easy to synonymise ‘digital’ with ‘technology’. But following Sam Bailey CMLI (p39), technology is a far broader term, encompassing the digital, mechanical, material and biological, in “the application of scientific knowledge for practical purposes, especially in industry.”

How digital technologies integrate with other forms of technology, as well as other forms of life and nature, is what gives them their strength. It’s also what makes them so effective at bringing industries together in sight of shared goals – whether that be decarbonisation, environmental net gain, or community engagement. This ‘Digital’ edition of the journal explores how these technologies can be harnessed to progress the landscape profession, aid better collaboration and improve outcomes for people, place and nature.

“Central to this process is translating multidisciplinary inputs into a common language – data,” we learn from McGregor Coxall (p32). But “the primary challenge [for] landscape practice lies in the unique intrinsic characteristics of landscapes,” says Giuliana Santos (p20) and the fact that “access to digital networks depends on who you are, where you live, what you can afford and the government you live under,” says Ed Wall (p15).

This perspective puts digital technologies at an emergent front between the arts, sciences and built and natural environments. It is therefore vital that landscape professionals are the ‘synthesiser’

(p12), so that the outcomes are landscape-led.

This edition of the journal follows on from the success of the Digital Practice & Technology for Landscape conference in July this year, the Landscape Institute’s (LI) first in-person conference since the pandemic. The LI extends its thanks to all the speakers and attendees on the day, as well as those who have contributed articles here, in particular the members of the LI’s Digital Practice working group and its chair, Mike Shilton CMLI, whose knowledge and input have been invaluable.

Josh Cunningham Managing Editor

PUBLISHER

Darkhorse Design Ltd

T (0)20 7323 1931 darkhorsedesign.co.uk tim@darkhorsedesign.co.uk

EDITORIAL ADVISORY PANEL

Saira Ali, Team Leader, Landscape, Design and Conservation, City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council

Stella Bland, Head of Communications, LDA Design

Marc Tomes CMLI, Director, Allen Scott Landscape Architecture

Sandeep Menon, Landscape Architect and University Tutor, Manchester Metropolitan University

Peter Sheard CMLI, Landscape Architect

Jaideep Warya CMLI, Landscape Architect, Allies and Morrison

Jane Findlay PPLI, Director FIRA Landscape Architects

LANDSCAPE INSTITUTE

Managing Editor and PR & Communications

Manager: Josh Cunningham josh.cunningham@landscapeinstitute.org

Proof Reader: Johanna Robinson

President: Carolin Göhler

CEO: Rob Hughes

Head of Marketing, Communications and Events: Neelam Sheemar

Director of Policy & Public Affairs: Belinda Gordon

Landscapeinstitute.org @talklandscape landscapeinstitute landscapeinstituteUK

Print or online?

Landscape is available to members both online and in print. If you want to receive a print version, please register your interest online at: my.landscapeinstitute.org

Landscape is printed on paper sourced from EMAS

(Environmental Management and Audit Scheme) certified manufacturers to ensure responsible printing.

The views expressed in this journal are those of the contributors and advertisers and not necessarily those of the Landscape Institute, Darkhorse or the Editorial Advisory Panel. While every effort has been made to check the accuracy and validity of the information given in this publication, neither the Institute nor the Publisher accept any responsibility for the subsequent use of this information, for any errors or omissions that it may contain, or for any misunderstandings arising from it.

Landscape is the official journal of the Landscape Institute, ISSN: 1742–2914

© 2024 Landscape Institute. Landscape is published four times a year by Darkhorse Design.

Redefining the relationship between urban spaces and the ecosystems that sustain them with McGregor Coxall. Find out more on page 32.

FEATURES

8

The lay of the land: A landscape perspective on artificial intelligence

Denise Chevin looks at the implications of AI for the sector

20

Seeing double: The landscape of digital twins

Applications of digital twins in landscape practice

31 Conference insight: Golden rules for landscape BIM modelling

Key takeaways for landscape professionals

15

Imperfect forms of public space – even in a digital age

Ed Wall provides insights from the University of Greenwich Centre for Spatial and Digital Ecologies

18

Yukako Takanashi argues that data centres can be sites that contribute to nature recovery A landscape-led approach to data centre design

25

Digital Frontiers: Reshaping landscape through data CASE STUDY CASE STUDY

Pioneering work at the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park

26

Scoop behind the foliage: How information shapes landscape

Thomas Yunqing Bai on the data revolution

Living Infrastructure: A digital approach to urban ecosystems 32 CASE STUDY

McGregor Coxall’s Biourbanism Lab is transcending disciplinary silos to address complex urban challenges

Three industry perspectives on key technologies for implementing Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG)

Insights on key technologies for reducing project carbon, from the Landscape Institute Landscape and Carbon Steering Group

Denise Chevin sets out the basics of artificial intelligence, explores its application in landscape practice and highlights implications for the future of the profession.

1. AI-assisted rendering of landscape project.

Credit: Nick Tyrer

From smart assistants like Amazon’s Alexa to spam filters on your email, to online chatbots and robotic vacuum cleaners, artificial intelligence (AI) has been incrementally impacting our everyday lives without many of us even registering it.

Over the past 18 months these advances have been moving at warp speed, with the development of

so-called generative AI. New tools are fundamentally changing the way creative professionals work –landscape practitioners included.

Generative AI, in the form of ChatGPT, Microsoft Copilot and image creation models like Midjourney, DALL-E3 and Stable Diffusion, to name a few, has the potential to provide huge efficiencies in concept design and is taking the strain of more

administrative activities like generating reports and writing submissions.

Coupled with other still-embryonic software, this offers huge potential in devising and planning landscape in consideration of biodiversity, climate and soil conditions. These tools can potentially help streamline workflows, reduce costs and ensure that the design is environmentally sound. The prospect is being met in the landscape

community with an understandable mixture of trepidation about job security and excitement at the creative possibilities it offers and so at this stage its use comes with a health warning: AI in all its formats should be used as a starting-off point, not a panacea.

“We’re in the full-on experimental phase, where most people are playing with off-the-shelf products to see what’s possible,” says Phil Fernberg, Director of digital innovation at USbased landscape consultancy OJB and a member of the American Society of Landscape Architects, who holds a PhD in AI and landscape architecture. “But as far as full business transformation or workflow integration, that’s still in the beginning. People are still trying to figure out how to use it.”

So what is artificial intelligence?

AI is software that can analyse large amounts of data, recognise patterns and make predictions or decisions based on that data, continuously improving its performance over

time. According to Fernberg, “AI is a whole umbrella of different ways of approaching automation and there are different ways of conceptualising and characterising it. One way is according to its abilities, of which there are three categories.”

These categories are, firstly, artificial ‘narrow intelligence’, which is the capability to perform a discrete task or a discrete set of tasks – like virtual assistants. Secondly, artificial ‘general intelligence’ is where it’s getting into the ability to perform generally on a wide range of tasks, just as humans would in novel environments and novel contexts and at the same rate as humans, like driving a car and this is still a work in progress. And then, thirdly, there’s artificial super intelligence, where it surpasses that of humans and is still in the realms of science fiction.

“When most people talk about AI these days they are talking about generative AI – so that’s programs like ChatGPT, DALL-E and Midjourney,” says Fernberg.

These types of programs are still classified as ‘narrow intelligence’ but operate at a game-changing level. They use deep learning from vast amounts of data taken from the internet (or internal documents) to analyse and understand text or images and then generate their own output based on prompts provided by the user.

Alan King, head of global membership development at

When most people talk about AI these days they are talking about generative AI –so that’s programs like ChatGPT, DALL-E and Midjourney.

IMechE and founder of AIYourOrg. com, says, “If you’re asking AI to generate a picture of a cat, it’s looking at millions of pictures of cats and then asking itself, ‘What does a cat look like?’ Then it creates an image that it thinks answers your question.”

When it comes to landscape images, generative AI programs

can generate multiple design variations, exploring numerous possibilities based on parameters like space constraints, environmental conditions and aesthetics. For landscape designers, bespoke software is being developed in the form of plug-ins to existing design that can help create optimised outdoor

environments, adjust landscape layouts quickly, or create planting plans and assess irrigation needs.

‘Democratising’ landscape design

Such is the speed of development that it’s off-the-shelf general programm that have been shaking up the design sphere because they are so easy to use.

Nick Tyrer is a practice leader in computational design and research at BDP Pattern, the sports and entertainment division of BDP. An architect by training, he has been using generative image tools like Midjourney to help create concepts for competition submissions where requirements are visual rather than necessarily requiring full landscape considerations.

“The AI image-generating tools are very good from a designer’s perspective, whether you’re an architect or a landscape designer. You can open the program and just start describing what you want and it will generate an image, based on your prompts. It might not be what you want, but it might be close and you can just keep honing it with more prompts. Alternatively, you can use it just for inspiration.”

Tyrer finds that current constraints are to do with biases in training data and potential reinforcement of existing stereotypes. For architects, that amounts, for example, to a prevalence of American-style architecture in AI-generated images of houses. He warns that, used naively, the tools can lead to a false sense of creativity and the designer simply presenting random, unoriginal content.

Tamae Isomura, senior landscape architect at Ground Control, echoes many of these sentiments from her experience of experimenting with AI tools. She observes how generative AI is a potential threat to the work of landscape designers, but is also providing benefits.

Ground Control is a design and build contractor which works entirely digitally, using traditional computer aided design (CAD), Geographical Information Systems (GIS) and 3D modelling. Plants are included in BIM models, specifying the plant species

and Autodesk’s Revit is also used for planting plans.

Isomura says that they are using image-based generative AI mainly for concept development, brainstorming with the software to generate ideas, as well as improving design statements and identifying areas for improvement based on previous projects. The company is also testing Microsoft Copilot Pro, which can be customised by scanning and searching internal documents saved on the company server. In practice, Isomura says you might prompt the tool to write up the design statement from the rendered plan or drawings, which would produce a basic structure of the concepts and description. You might then ask how the design might be improved and the AI would search previous projects from the internal files saved on the server and suggest various ideas.

“It is useful as a time-saving tool. It’s not perfect but the pace of improvement at the moment is dramatic so we can see the potential,” she says.

Isomura also sees some potential downsides – and is concerned that AI could tempt some practices to replace junior roles in design, particularly in

the early stages of projects, such as pre-planning concepts where the landscape professional’s input is often visual.

She also observes that Ground Control often finds that they will have to redesign schemes at the construction stage if the visual concepts are generated by others using AI without any landscape qualifications. “It might be that because of the retaining wall, the planting doesn’t work in a given area, because of the soil conditions or the micro-climate.”

Isomura adds that it is possible to use AI for planting while also taking into consideration the site conditions and site layout scenarios, but it needs to be validated by experts.

“For me, the important thing is that landscape practices do not replace the junior landscape architects with AI, because we need to develop the future generations to have human intelligence. We need to give people the opportunity to learn.”

Designers across the board flag up the issue of copyright as another major concern. Fernberg says the unattributed use of imagery has become like the “wild west”. He and

others point to general confusion, user terms evolving on the hoof and the need for clear legal frameworks to be developed.

As well as the ethics of intellectual property and of creativity and creative agency in the design process, another worry for some is the environmental implications. “The data centres powering generative AI models are power hungry and therefore carbon intensive,” says Fernberg.

There is an industry consensus that AI can be a useful assistant. But with all parts of the design process being pervaded in some way by AI, there is also a strong general view that it will only be a matter of time before these systems are joined up and the whole design process becomes more automated, with designers acting in the role of ‘’synthesiser”, as Fernberg describes it.

“You won’t see it for a while, but what you will see is that some of those individual elements of the design process will be made far more efficient and completely transformed. And they’ll link in with systems that were already around even before

4. AI-generated planting image, generated in Midjourney with prompt: landscape architecture, planting bed, rudbeckia, buxus, lavender, rosemary, trees.

For me, the important thing is that landscape practices do not replace the junior landscape architects with AI, because we need to develop the future generations to have human intelligence. We need to give people the opportunity to learn.

generative AI – like parametric design and greater machine learning models for spatial data – to transform the entire design process.”

Professor Andy Hudson Smith, from the Centre of Advanced Spatial Analysis at UCL, paints a similar picture. One of the projects he is involved with is converting Met Office data into written text and using AI to generate landscape images, to understand what AI can create from data feeds and whether it can generate realistic representations.

“The technology is advancing monthly. If you’re a landscape designer, you might cut and paste your client’s brief into an AI program and see what it comes up with. And it will probably come up with something which is wrong. But roll forward two or three years and it’ll probably come up with the plans, the drawings, look at the long-term flooding and storm water management, drought-resistant planning, carbon footprint and write your client report at the same time.”

“What is also attractive about generative AI is you can write software yourself. I’m an urban planner with a geography-based background, yet I can write software using ChatGPT and ask it to build the things that I want to do. So suddenly you become the expert in almost all things, because you can build the software.”

Alan King is also convinced of the huge impact AI will inevitably have.

“As we go forward, these models are going to become supercharged,” he says. “Most AI systems require a lot of human interaction and input and prompting to get to the kind of output you might desire. But over the next five to ten years, the capability is going to get better exponentially, with AI programs solving tasks together and taking humans out of a number of steps in the loop.”

“So you might produce a photograph of the land that needs to be developed, ask it to develop five possible designs and it will go away and do that. It will cost it, tell you

Carry your projects through from start to finish with the speed and reliability you require. With the latest in Vectorworks, you’ll find faster workflows at every stage of design, minimising interruptions and maximising productivity.

Start your free trial at VECTORWORKS.NET

where you can get all the materials you need and will pull the whole project together and give you the finished plan. And then it will be a case of choosing which one you’re going to work with.”

It seems that the industry is set to change significantly in the years ahead. But while much of what has historically been the job of a landscape designer may become automated, currently the expertise, skill and intelligence of a human would still be essential for choosing which of those five possible designs would be best. As long as that is the case, it will remain essential that landscape professionals are trained, educated and engaged in the process, so that the outcomes of projects are landscape-led. As Dr Fernberg says, it’s about being the synthesiser.

Denise Chevin MBE is a freelance writer and editor specialising in the built environment and is a former editor of Building Magazine.

What is also attractive about generative AI is you can write software yourself.

¹ https://www. routledge.com/ Contesting-PublicSpaces-Social-Lives-ofUrban-Redevelopmentin-London/Wall/p/ book/9781032163567? srsltid=AfmBOopt4cfK Zr2NucAzX8GoIoZULE

rrtTxFQbUbqSVHdwVe

W0_X8qx4

Through a series of vignettes, Ed Wall explores tensions across old and new public platforms, revealing the entanglement of spatial and digital ecologies and far-from-ideal forms of public space.

Ed Wall

How have public spaces changed? In recent work, I settled on defining public space as sites and practices of coming together around issues of concern¹ – places that are inclusive of the social and spatial relations of streets and squares, cafes and pubs, town halls and libraries, newspapers and television news, political meetings and violent protests. While none of these are perfect forms of public space, claims of some digital platforms as sites of free speech and emerging democracy require a rethinking of what public spaces can be.

Media

It has long been accepted that social media platforms create public spaces for coming together, sharing and debate. With the advent of platforms like Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, public space has expanded, like it did in the 17th century with the

innovation of printed newspapers. Published media disseminates issues of interest, it provides forums for people to come together and it has the power to hold business interests and elected officials to account. New ecologies of digital public spaces have been further formed as print media migrates to online platforms, leaving behind their declining print sales.

Despite fears that physical spaces of public discourse would also disappear into the web, in some UK cities over the last four decades the number of publicly accessible landscapes has grown. Many new forms of public space have also emerged, but these are often not the state-mandated forms of community parks and town

squares that we were familiar with in the UK up until the 1980s, or even through the New Labour government of the 1990s. Instead, we see largely privately owned public spaces financed by corporate interests and facilitated by local, metropolitan and national government.

There have long been varying forms of public space in cities like London where streets, squares and parks are owned and managed by the different councils, government departments, the Crown Estate, housing associations, commercial developers, private landowners and more. But when their terms of ownership and publicness significantly shift, it could be argued that these sites are no longer effective public spaces. They become seen as compromised platforms for governments or corporations to push partisan agendas that serve commercial interests. Concerns in the digital realm are similar. In 2022, Elon Musk claimed that Twitter was a ‘de facto public town square’ and that ‘Free speech is essential to a functioning democracy.’² When he acquired the platform, Musk fired content moderators in order to make speech less regulated. But as behavioural scientist Douglas Yeung wrote, ‘Firing all the rangers might let anyone walk into national parks, but trails would go unmaintained, trash would pile up, traffic would snarl and the majestic landscapes that attracted everyone to begin with would suffer.’³

The lack of regulation of big technology companies has left the publicness of their social media increasingly skewed. But as with historic tensions regarding physical public spaces or traditional news outlets, where self-regulation has long been argued for, governmentimposed controls raise concerns about free speech and independence. The nature of regulations and policing impacts publicness and the motives behind these controls can push them further towards a private realm. When journalists critical of Musk are excluded from X⁴ for reasons beyond the platform’s ‘terms of service’ the

publicness of this town square comes into question.

Much like the privately owned public spaces that dominate many contemporary cities, the private ownership of social media platforms –whether by individuals or corporations – makes a difference that many commentators struggle to reconcile with traditions of public space. But just because Musk bought Twitter and changed the name and rules for the social media platform, this does not preclude its presence as a public space. While all public spaces have restrictions placed on them, by varying combinations of governments, owners and managers, the rules also establish tensions which contribute to the contested politics that frequently plays out within these spaces.

Public spaces are of course not neutral containers of political activities or impartial platforms across which public life is performed. Whether in city halls or online forums, there are always limits to public spaces, from legal boundaries to digital surveillance cordons. To simultaneously advocate for free speech while restricting users of the platform to do so is a paradox, as we have seen play out across digital and physical realms. Public spaces are not free spaces and town squares have never been synonymous with free speech. To claim otherwise ignores long histories of public space exclusions, told through the experience of women, homeless people, marginalised groups and enslaved populations that have in the past been shut out of public life.

² https://x.com/ elonmusk/status/ 150777726165460582

8?lang=en

³ https://www. rand.org/pubs/ commentary/2023/01/ the-digital-town-squareproblem.html

⁴ https://newrepublic. com/post/177936/ twitter-suspendsaccounts-journalistscritical-elon-musk

⁵ https://placesjournal. org/article/a-city-is-nota-computer/#ref_34

⁶ https:/theconversation. com/jan-6-was-anexample-of-networkedincitement-a-media-anddisinformation-expertexplains-the-dangerof-political-violenceorchestrated-oversocial-media-220501

⁷ https://www. routledge.com/ Contesting-PublicSpaces-Social-Lives-ofUrban-Redevelopmentin-London/Wall/p/book/ 9781032163567?srsltid =AfmBOorH5rgI9L33Z fyEuGmpTV4PseHRXU XsZcqWYuRuzzvcSq O4-oVw

Public spaces are now designed, managed and used spatially and digitally: landscape architects plan simultaneously for CCTV surveillance and Instagrammable scenes; global events are broadcast from one city onto large pop-up screens in another; and everyday functions of waste collection and traffic control are managed with smart technologies and digital twins. But can digital be the answer to such a plethora of spatial problems? The writer Shannon Mattern cautions against such an embrace of digital technologies: ‘the city as computer’ she claims, ‘appeals because it frames the messiness of urban life as programmable and subject to rational order.’⁵ It is also unlikely that the inefficiencies of a public life that are produced through many diverse actions would survive the rational mind of computer scientists or the drive for profit of corporate owners.

We can recognise that digital technologies have accelerated public debate and public actions – online and on our town streets. Issues of concern, like violence that has disrupted communities, rapidly draws angry publics together, often to spill back into urban public spaces. What has been termed ‘networked incitement’⁶ can be seen around the world, including the role of social media platforms in the January 6 insurrection in Washington DC in 2021, or the UK summer riots in 2024. Events in public spaces, whether cultural celebrations or political demonstrations, have also recognised that digital platforms are essential to amplify their message or generate

more revenue. Political organisers know that photos of single protesters with bold signs are more attractive to media audiences than the issues around which public demonstrations form.⁷

Despite a spatial-digital hybridity evident in many urban public spaces, the planetary expansion of digital networks and what the philosopher Nancy Fraser terms ‘transnational publics’ points to further forms of spatial-digital public landscapes. Disparate networks of activists and communities, which come together to raise concerns around collective issues, from climate change to racial justice, define new public spaces. These constellations of public spaces have been facilitated by the expansion of digital networks and access to social media. They are frequently grounded in specific landscapes, where impacts such as those of global warming or racial discrimination are most pronounced. The entanglement of spatial and digital public spaces provides a means to form collective action while revealing the relations between where decision makers reside (usually capital cities), landscapes impacted by these decisions (frequently less visited places) and public sites of resistance (more visible city squares and media platforms).

Public spaces are unevenly distributed and not consistently accessible. The provision of public spaces between and within cities is rarely fair. Restrictions and regulations imposed on public spaces also vary between nation states. Access to digital networks and social media platforms depends on who you are, where you live, what you can afford, the government you live under, as well as the rules of engagement of each platform. X is a distorted form of public space – but so was Twitter before Musk bought it. And while in a space like Trafalgar Square, its relation to the state may limit public rights to access and protest, this does not make X a ‘de facto public town square’. Social media is just one of many public places where people come together to form publics – even when the ‘terms of service’ are inconsistently enforced.

Ed Wall is the director of the Centre for Spatial and Digital Ecologies at the University of Greenwich and a visiting professor at Harvard University. He is the author of Contesting Public Spaces: The Social Lives of Urban Redevelopment in London.

With an increase in demand for data comes an increase in demand for data centres. Yukako Takanashi highlights how a landscape-led approach can help these sites to contribute positively to local nature recovery strategies.

In the UK, there are over 500 data centres and the demand for data storage is continuing to escalate. The increasing use of cloud computing, big data analytics and digital services is driving high data storage and processing requirements, posing a challenge to industry and government.

According to Savills, the number of data centres will need to increase by almost 2.5 times by 2025 to meet the increased demand for storage in Europe.1 The Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) recognises this growing demand for data storage, processing and digital services, whilet the new Labour government has designated data centres as Critical National Infrastructure,2 and the revised National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) currently being consulted on emphasises that local planning authorities must make planning decisions that address the need for more data centres.3

However, data centres have a significant environmental impact, from energy consumption and land requirements to water consumption and ecological footprint. Reducing the overall consumption and carbon impact of data centres demands further research, design innovation and policy. Some progress is being made by major tech giants including Microsoft, Amazon and Google by sourcing energy from their renewables projects or through Power Purchase Agreements (PPA). For example,

Amazon’s wind farm projects in Bäckhammar and Microsoft's PPAs in Sweden and Denmark sourcie contracted electricity from wind and solar farms.4 But on a global systems scale, there is much work still to do.

So, what can landscape architects offer? Landscape design for large industrial sites has historically been driven by functionality and stringent security, serving the primary purpose of the facility. However, the design ethos for digital infrastructure is on the verge of significant change and landscape designers should play a key part in enabling these sites to become more outcomes-led, to make a positive difference to local nature recovery. Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) is now a mandatory requirement in

1 https://www. savills.co.uk/ insight-and-opinion/ savills-news/336014-0/ savills--pipeline-ofdata-centres-needs-tomore-than-double-by2025-to-meet-demandfor-storage-in-europe

2 https://www.gov.uk/ government/news/ data-centres-to-begiven-massive-boostand-protections-fromcyber-criminals-and-itblackouts

3 https://www. montagu-evans.co.uk/ articles/switchinggears-can-planningreform-accelerate-datacentre-development/ 4 https://www. datacenter-forum.com/ microsoft/microsoftsigns-ppas-in-swedenand-denmark

https://www. aboutamazon.eu/news/ sustainability/amazonsfirst-operationalwind-farm-in-europedelivers-clean-energyto-sweden

https://cloud.google. com/blog/topics/ sustainability/cleanenergy-projects-beginto-power-google-datacenters

5 Method based on The Biodiversity Assessment using Biodiversity Metric 3.1 (Natural England 2022)

6 Footprint data based on Gensler data centre projects

England and this legislation must be leveraged alongside robust strategies for green infrastructure, landscape character and environmental assessment, incorporating regenerative design principles and utilising land efficiently to unlock the contextual value of sites.

A standout example is a six-hectare data centre campus in south-east England, designed by Gensler Architects and Landscape team. Sitting within the London green belt, the site is currently occupied by industrial businesses and contains a Grade II-listed building which is a reminder of the former farmland.

The project aims to revitalise the site with the introduction of a quality data centre, with the listed building as a functional office at the heart of the development. Surrounding the data centre facilities are a plethora of rich landscapes, connecting the industrial site to the green belt.

The aspiration for the landscape proposal is to restore the aesthetic farmhouse setting, while providing site-wide green infrastructure for ecological enhancement. This is addressed by a mix of green infrastructure including swales and raingardens, an intense biodiverse corridor of scrub planting, species-rich wildflower meadows and green walls.

The landscape strategy is built upon the established biodiversity of the surrounding context, encouraging a diverse ecological habitat. The proposed scheme will increase the green infrastructure coverage from 4% to 26%, resulting in an on-site net habitat gain of nearly 4,000%.5

Data centre footprints in a rural context tend to be in the region of 50–60% of the total project area.6 What’s left is for external uses, such as road circulation, security, stormwater ponds, raingardens, swales and landscape buffers. These spaces provide a significant opportunity to enhance local nature recovery and environmental net gain and help to ensure that degraded brownfield sites can be brought back to life as part of ongoing planning reforms. A landscape-led approach, as ever, is key.

Yukako

Takanashi CMLI is a Landscape Design Manager and Technical Lead at Gensler London.

WSP UK BIM Lead, Giuliana Santos, looks at the trajectory of digital twins within the landscape sector and what potential they hold for the future.

Giuliana Santos

With the rapid expansion of urban areas, sustainable, efficient and resilient city planning is crucial. Emerging technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT) and digital twins, are revolutionising design, management and interaction in the built environment. Together, these technologies are underlining the need for landscape disciplines to collaborate digitally within the construction industry. While Building Information Modelling (BIM) has been a stepping stone in this journey, it is digital twins that now capture the imagination and meet the growing demands of clients, alongside rapid advancements in AI.

Digital representations offer a more compatible, responsive and

user-focused approach to designing the environments we live in. The primary challenge in applying the technology to landscape practice lies in the unique intrinsic characteristics of landscapes and their interrelations. So how can digital twins support a landscape-led design approach, improving data management and delivery?

Taking a step back to how BIM emerged, this technology has historically been connected to aerospace design and development, aiding in visualisation, performance testing and design optimisation when building aircraft prototypes. The term ‘digital twin’ was then coined by NASA’s John Vickers in 2010,¹ with NASA being a forerunner in adopting the technology. Today, NASA’s Earth System Digital Twins (ESDT) continue to merge models of both Earth and human systems with continuous observations and information systems, offering unified, detailed representations and forecasts for monitoring information and providing decision support.

Taking this across into landscape, Digital Futures in Landscape Design: A UK Perspective,² by Mike Shilton CMLI,

chair of the Landscape Institute Digital Practice Group, explores the role of BIM in reshaping the construction industry to address environmental challenges. It highlights how BIM supports design, construction and waste reduction and enhances decision-making processes. “All too often BIM is focused on delivering efficiencies and improvements during the design and construction phase of a project and we lose sight of where the most significant savings can be realised: the lifetime management and ongoing maintenance of the asset,” the article says. Indeed, with relevance across various industries, digital twins have the potential to create more sustainable, healthier environments. They can achieve greater efficiencies to minimise waste and emissions and enable data-driven decisions that improve the health and sustainability of urban green spaces. As Shilton’s article argues, “The digital twin concept not only uses the virtual model to build the real world, but through sensory feedback, becomes a real-time dashboard of how the asset is performing.”

¹ https://www. technologyreview. com/2024/06/10/ 1093417/how-digitaltwins-are-helpingscientists/ ² gispoint.de/fileadmin/ user_upload/paper_ gis_open/DLA_2021/ 537705028.pdf

1. WSP’s Demystifying digital twins

© 2024 WSP

2. WSP’s Digital Twin Guide Levels of Maturity

© 2024 WSP

At WSP Global, we define digital twins as a dynamic digital representation of the built and natural environment that can be used to plan, visualise, report on and control assets and operations.

³ https://www.wsp. com/en-au/news/2022/ wsp-tool-demystifiesdigital-twins

⁴ https://oecd-opsi.org/ innovations/land-iq/

Digital twins vary in complexity and capability based on an organisation’s digital maturity and desired outcomes, ranging from simple data visualisation tools to comprehensive platforms. WSP’s Digital Twin Guide³ applies three key dimensions: the size of the asset(s) to be twinned (Size), the asset life cycle stage (Lifecycle) and the maturity of systems and available data (Data Maturity). The interactive tool allows users to explore how a digital twin can benefit a specific project, asset, or group of projects or assets, providing practical insights into the application of digital twins in a professional context. Digital twins can be managed and adapted for different uses across project life cycles by integrating multiple data sources such as BIM models managed on common data environments (CDEs), survey data, GIS, point cloud models, reality data such as photogrammetry and others. The data is input into the digital twin and seamlessly combined with relevant information such as weather patterns, topography, biodiversity, plant species monitoring and land use data.

4.

Digital twins can be used to support planning applications and facilitate public consultations and work to bring together specialists in mobility, accessibility, health and safety for collaborative decision making. For example, in collaboration with Giraffe and Aerometrex, WSP Australia has developed Land iQ,⁴ a groundbreaking spatial tool to revolutionise land use planning for the local government. Land iQ is a dashboard that can be used to identify

sites with a set of criteria, undertake site layouts and feasibility studies and make preliminary assessments of business cases. It assists strategic planning and development by analysing data from local to regional scales, helping planners to understand existing economic, social, demographic, cultural and environmental contexts. Land iQ is underpinned by over 40 land use typologies, enabling a consistent approach to scenario analysis across government.

The models can then assist with data analysis and simulation during the design phase, interrogating the 3D model, design validation, clash detection, quality checks, improvements, data extractions, carbon footprint analysis and visualisation, informing decisions throughout construction phases.

In this fashion, WSP has developed a simulation workflow using iTwin and Unreal Engine to test the design before building it, using virtual reality (VR) and human-centred design (HCD) with end users. The method commences by converting BIM data into a VR digital twin. Subsequently, behavioural tests are developed, followed by expert design evaluation and refinement. Once refined, the model is ready for public consultation, assessment and analysis by behavioural scientists and recommendations. Finally, the design undergoes further refinement. This process can be tailored to projects and address design challenges in

public spaces, such as accessibility, security and evacuation, wayfinding, environmental comfort including air, acoustics, wind, temperature, vibration, shading and delivery monitoring. At each stage of the process, the digital twin acts as the central tool of effective collaboration and decision-making.

When discussing digital twins, we must consider their use in conjunction with the Internet of Things (IoT). IoTs have the potential to revolutionise city operations by enabling real-time monitoring, data collection and automation. By embedding sensors in physical objects and connecting them to the internet, the IoT enables a more targeted response to maintenance, for example by embedding moisture content sensors in soils and tree pits, which alert managers when watering is required.

For the Metro Tunnel Environment Monitoring Platform, a project involving

the construction of a new 9km twin tunnel and five new stations underneath Melbourne’s central business district, at a cost of AU$11 billion, several environmental performance requirements were set. One of the station sites, Parkville, is surrounded by a range of sensitive environments including animal laboratories, radiotherapy machines, sensitive electron microscopes and medical and legal institutions. WSP, in collaboration with Arup, developed a plan to keep track of 132 categorised, labelled ecological requirements. Called the Metro Tunnel Environment Monitor, the system monitors noise, vibration and air quality so that the sensitive environments can be monitored. It uses a combination of digital twins and an IoT to make the validation possible, storing telemetry, analysing and processing data, providing easy access to raw data through a user-friendly interface, sending instant alerts and offering reporting workflows.

Despite the potential that the IoT and digital twins offers landscape design and management, several challenges must be addressed to realise their full benefits. Unlike buildings, living systems are dynamic and constantly adapting to various factors, including weather, soil conditions and human activities, which can make data collection and analysis difficult. Moreover, deploying IoT sensors in outdoor environments presents challenges due to weather conditions and the potential difficulties involved in fixing them in strategic locations, where they are able to capture accurate and meaningful data. But there are many opportunities for landscape architects to use the technologies. They can be used to simulate the impact of different landscape designs on local ecosystems, helping to create environments that support a diverse

range of species. There is also huge potential to assess the benefits of green infrastructure, such as green roofs, rain gardens and urban forests. Projects could monitor plant biodiversity, shading and growth by combining multiple data sources and it is worth noting too that use of this technology does not have to be complex. For simple data tracking, a ‘dashboard’ can be built using a website, or a Microsoft PowerBI form linked to the data, making it universally accessible.

As digital twins evolve, their adaptability will encourage collective efforts to shape their use and align with industry-specific demands. By integrating these technologies into landscape management, professionals can unlock new opportunities to enhance the health and functionality of green space, while addressing critical environmental challenges such as climate change, resource scarcity

As digital twins evolve, their adaptability will encourage collective efforts to shape their use and align with industry-specific demands.

and biodiversity loss. In a world where urbanisation and ecological pressures are increasingly required, the ability to integrate BIM, IoT and digital twins with living systems will be a critical factor in shaping future cities.

Giuliana Santos is a Landscape Designer and BIM Lead at WSP UK

THE JOBS BOARD FOR THE LANDSCAPE PROFESSION

The LI Jobs Board is the best way to get your landscape role or project opportunity in front of a wide audience of qualified applicants.

KeySCAPE

KeySCAPE offers a single solution that takes you from concept, through detailed design and contract documentation and beyond.

KeyTREE offers compliance with the latest British Standard and includes many features to help you create clear and readable tree survey drawings inside AutoCAD. GET THE LATEST UPDATES!

KeyTREE

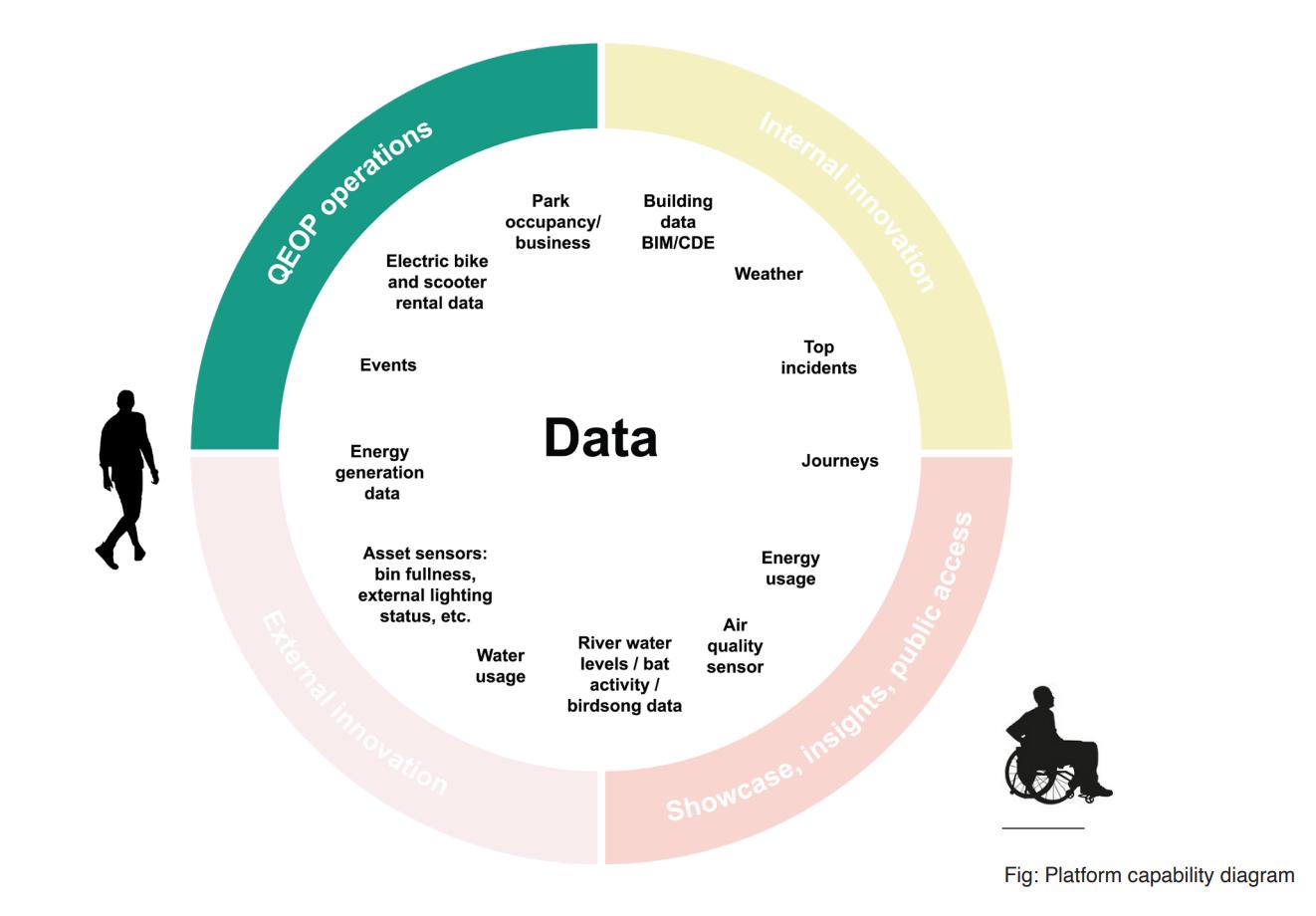

The Digital Frontiers project at Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park (QEOP) is pioneering a new approach to urban spaces, where the physical and digital realms converge.

Professor Andrew Hudson-Smith & Professor

Duncan Wilson

The Digital Frontiers project is an innovative data ecosystem aiming to transform how we understand, manage and design urban landscapes.

Run jointly with SHIFT (a catalyst for east London’s innovators, bringing together business, academia, government and local communities) and University College London’s Connected Environments Lab, the project aims to offer new and emerging opportunities through access to and understanding of data relating to the physical landscape. Real-time data streams from across Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park are being made openly accessible to provide insights into the hidden life of the park that were previously unattainable. For example, urban heat island effects can be mapped in detail, allowing for targeted interventions in landscape design.

Biodiversity monitoring, from butterflies through to the real-time tracking of bats from audio sensors enables a deeper understanding of how landscape elements impact local ecosystems. Park usage patterns, captured through Wi-Fi and mobile data, inform more responsive design decisions and water usage. Data from buildings and waterways supports more sustainable water management strategies in landscape design. Above all, the system opens up data to all stakeholders, to share, view and analyse data from the park.

The technological backbone of this system is based around both Internet of Things (IoT) sensors and Long Range Wide Area Networks (LoRaWAN), creating a mesh of data collection points throughout the park. This data and network feed is being utilised to create a bottom-up digital twin of the park to support collaboration and virtual

experimentation with landscape modifications before physical implementation. Not only does this enable visual insight into proposed landscape interventions, but via simulation techniques, also the ongoing impacts of both design and policy choices.

These emerging technologies are aimed at enabling landscape architects and urban planners to move beyond static, point-in-time analyses to dynamic, responsive approaches. The integration of diverse data streams – from air quality to energy usage – provides a holistic view of the urban ecosystem, informing more comprehensive and sustainable design strategies.

The implications of this approach extend far beyond QEOP. The open-source model for real-time data has the potential to scale to city-wide or even national implementation, transforming evidence-based policymaking for urban environments. Landscape architects could play a crucial role in interpreting and applying this wealth of data to create more resilient, sustainable and userfriendly urban spaces.

Andrew Hudson-Smith is Professor of Digital Urban Systems and Duncan Wilson is Professor of Connected Environments at The Bartlett Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis. See the full report at shiftlondon. co.uk/shift-announces-digital-frontiers-roadmap/

LI Digital Practice Group member Thomas Yunqing Bai CMLI charts the what, why and how of information management in landscape practice.

3.

Thomas Yunqing Bai CMLI

Landscape architecture is often seen as a profession focused on the beauty of plants, nature and outdoor spaces, with designs traditionally communicated through drawings, images and photographs. However, there’s much more to the field than meets the eye. Behind the delivery of every garden, park or public space lies a complex system of information management. Handling this information is crucial not only for ensuring the successful completion of projects, but also for meeting industry standards and fulfilling contractual obligations. In the past, landscape architects managed this information mostly on paper. Contracts, drawings and project details were stored in large filing rooms and communication often relied on physical documents, with some firms still using fax machines until relatively recently. While these methods worked for a time, they had many drawbacks. Finding specific information was often difficult and revising or updating designs could be a slow, manual process, but as digital technology advanced, the landscape architecture industry began to shift towards more efficient ways of managing information.

Our practice, Ares Landscape Architects, is a good example of this transformation. Like many other practices, we initially relied on manual processes for our design work. We stored documents on paper and while we created 3D models, they were mainly for visual presentations rather than being part of a larger information system. This approach was common across the industry, where information management was often inefficient.

In 2016, we took a significant step forward by adopting Vectorworks, a drafting software compatible with Building Information Modelling (BIM). Integrating BIM into our workflow allowed us to manage information in a more organised way, aligning with new industry standards. By 2018, we had fully embraced BIM Level 2 compliance, which was later replaced by the UK BIM Framework, incorporating both 2D and 3D

modelling along with alphanumeric data. This shift wasn’t just about using new software; it fundamentally changed how we approached design, documentation and working with others.

Transitioning from traditional methods to a BIM-based process came with its challenges. One of the biggest was resistance to change. Moving away from familiar ways of working required a shift in working culture. Employees needed training not only on the new software but also on new ways of managing and thinking about information. Another challenge was the sheer amount of data that needed to be included in the BIM models. Beyond the 3D geometric data, requirements also include alphanumeric information such as facility, object and specificationrelated asset data. Ensuring that this

data was accurate, up-to-date and accessible required the development of new workflows and the adoption of data management practices.

The landscape industry also faced the challenge of adapting BIM – originally designed for building and architecture– to the specific needs of landscape projects. Many existing BIM standards didn’t directly apply to landscape work, leading to gaps between the available tools and what landscape architects actually needed. This often meant that landscape architects had to find creative workarounds to make BIM work for their projects. On one hand, the standardisation required by BIM extensively streamlined the design and delivery process of projects. On the other hand, it also restricted the flexibility and creativeness of the information output.

New digitised practice also brought new risks, such as the possibility of data corruption, ownership of changes, cybersecurity threats and the loss of important information by technical failure. While digital systems made it easier to store and share information, they also increased the chances of hoarding unnecessary information, mistakes and security breaches. This required firms to implement new protocols to treat and protect their data.

Despite these challenges, the benefits of adopting BIM and digital information management have been substantial. One of the most important advantages has been the improvement in the accuracy and quality of project delivery. By bringing all relevant information together into a single model or from a single source, landscape architects can produce more accurate designs, reducing the likelihood of errors and ensuring that the final product meets the client’s expectations. Adopting BIM can be driven by the need to comply with public sector project requirements. Our work in the education sector for the UK’s Department for Education (DfE) required us to follow strict

BIM standards. The standardised processes enabled by BIM allowed us to efficiently manage multiple school projects, ensuring that each one met DfE’s design requirements within tight deadlines. The implementation of Common Data Environments (CDEs) has also made it easier for the design team, DfE and contractors to find information and track the progress of each project, providing greater transparency and accountability. However, BIM has also led us to more efficient workflows as a practice. The adoption of hybrid drafting and compliance with BIM information management standards, including the use of CDEs, has streamlined the design and documentation process for Ares. This has made it easier

7. Utilising geometrical data for detailed design and construction. © Ares Landscape Architects

for the team to collaborate, share information and ensure that everyone is working from the latest and same set of information. It dramatically enhances efficiency and makes project information easily accessible. Moreover, the ability to ‘pre-build’ projects in a digital environment has been revolutionary. Creating detailed 3D models allows landscape architects to spot potential issues and clashes with other consultants before construction begins. This proactive approach helps reduce costly mistakes, saves time and ultimately enables us to make better decisions.

Looking ahead, the landscape architecture industry is likely to further embrace BIM and other emerging

The landscape industry must remain vigilant to the potential risks associated with digital practice and information management. Cybersecurity will be an ongoing and increasing concern, not only in terms of protecting data from external threats but also in ensuring that information is properly managed and protected within the practice.

technologies to improve information management and project outcomes.

While BIM has already had a significant impact, there is still much potential to be unlocked, especially in landscape architecture, where its use is still

relatively new. The data assets in the model could offer benefits not only for construction, such as quantity take-off and costing, but also for laying the groundwork for future facility maintenance and management by the end users.

One promising area for future development is the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) into BIM workflows. These technologies could help automate daunting tasks like data entry and checking, freeing up time for landscape architects to focus on more creative and strategic design work. Additionally, data-driven processes by AI and ML could be used to generate multiple design options based on set criteria, allowing professionals to explore a wider range of possibilities and find the best solutions for each project.

Sustainability and carbon calculation are also likely to be key areas of focus for the future of BIM in landscape architecture. As the industry continues to prioritise environmentally friendly practices, BIM can play a crucial role in modelling the environmental impact of different design options by utilising integrated data and optimising resource use during construction.

As BIM and related technologies continue to evolve, all practices will need to keep up with the latest developments to ensure their processes remain in line with best practice. This will involve ongoing training and a commitment to continuous improvement.

The landscape industry must

remain vigilant to the potential risks associated with digital practice and information management. Cybersecurity will be an ongoing and increasing concern, not only in terms of protecting data from external threats but also in ensuring that information is properly managed and protected within the practice. As digital tools such as

AI become more integrated into the design process, the industry will need to develop new protocols to safeguard against copyright, data loss, bias and corruption, ensuring that information remains fair, accurate and secure.

As the industry continues to evolve, by embracing new technologies and prioritising

sustainability, the role of BIM will become more central to the practice of landscape architecture. However, it is crucial that the industry remains adaptable and continues to rethink how these tools can be used not just to meet client requirements but also to genuinely improve the design process and project outcomes.

Something I learnt at the LI’s Digital Practice & Technology for Landscape conference was, ‘It’s not about how the tech works, but how it works for us’. With a focus on collaboration, innovation and security, the future of landscape architecture in the digital age looks bright and promising.

Tamae Isomura chaired a discussion on BIM for landscape at the Digital Practice & Technology for Landscape conference. Here she reflects on the key takeaways.

Tamae Isomura CMLI

Landscape design encompasses both natural and built environments, making the task of landscape BIM modelling particularly challenging. But there are plenty of opportunities: integrating environmental analysis tools into planting design processes; streamlining manual workflows through digital automation; managing data and information; maintaining quality assurance – the list goes on.

Surrounding all of these benefits, argued Alejandro Masferrer Gatica, Principal BIM Manager and Abhinav Chaurasia, BIM Coordinator and 3D Visualization Specialist at Gillespies, is the ability of BIM to foster collaborative work and interdisciplinary coordination, bringing stakeholder alignment on complex project challenges.

Nehama Shechter-Baraban, landscape architect and BIM expert at Arch-Intelligence, put forward four golden rules to consider when using BIM for landscape.

– Start with existing site: Utilise BIM 3D modelling capabilities to understand site constraints, such as existing buildings, roads, work limits and areas designated for preservation. BIM can significantly enhance the understanding of the site in three dimensions before the design process begins.

– Transition to 3D models: Transitioning from 2D layouts to 3D models allows for enhanced design decisions. By leveraging the BIM model, designers can gather crucial information that informs and improves their design decisions. It is essential to understand the basic layout before diving into detailed modelling.

– Adopt a surface hierarchy: A landscape model is akin to a quilt, where every element, whether it be a path, plaza or slope, is carefully placed and integrated into the overall design. Rather than viewing the landscape area as one single, continuous surface, it should be approached as a collection of distinct parts. The hierarchy in modelling should follow this order:

1. Constraints: Identify and define the boundaries and limitations of the design.

2. Primary Surfaces: These are the main elements of the landscape, such as large open areas or key features.

3. Secondary Surfaces: These include smaller, detailed elements that complement the primary surfaces.

– Use a larger reference surface: Control the grading and overall topography of the site by using a larger reference surface, ensuring that all elements are properly aligned and integrated.

McGregor Coxall’s data-driven design philosophy seeks to transcend disciplinary silos in the built environment to address the complex interdependencies inherent in urban systems.

Michael Cowdy FLI and Jorge Sainz de Aja Curbelo

Planet Earth is a vast, intricate web of interconnected systems that sustain life. For millennia, humanity coexisted with these natural systems, our impact barely a whisper in the grand symphony of nature. However, industrialisation and urbanisation have dramatically altered our landscapes, introducing complex socioeconomic and environmental challenges that reverberate across cities worldwide.

With over half of the global population now residing in urban areas, cities have become the primary habitat for humanity. This rapid urbanisation has led to a host of challenges – pollution, habitat destruction, climate change and a rise in health issues ranging from respiratory ailments to mental health disorders. These challenges not only threaten urban populations’ well-being but also strain healthcare systems, energy resources and the resilience of both urban and natural environments.

Yet there is a growing realisation that cities and nature are not separate entities. A powerful shift in perspective is underway– one that seeks to restore and redefine the relationship between urban spaces and the ecosystems that sustain them. This vision emphasises the essential ecological services that underpin urban life, from air and water purification to climate regulation and mental health benefits.

Digital technologies are pivotal in helping us to realise this vision. Tools such as artificial intelligence, digital twins and data-driven design provide new insights that empower landscape practitioners to craft more resilient urban ecosystems. These technologies enhance decision-making, ensure design consistency and enable more efficient urban spaces. By harnessing these digital tools, we can develop integrated solutions to the urgent challenges of climate change, biodiversity loss and public health, ensuring that our cities not only survive but thrive in harmony with nature.

The Biourbanism Lab, McGregor Coxall’s research and development arm, drives this vision forward through innovative research and data analytics. The lab’s approach transforms data into actionable insights that directly inform design decisions. By linking research and design through data and using custom key performance indicators (KPIs), the Biourbanism Lab bridges the gap between vision and implementation.

This data-driven design philosophy is embodied in McGregor Coxall’s Living Infrastructure Framework, a holistic approach that integrates natural systems within built environments. The framework is organised around four key areas: social health and wellbeing, climate adaptation and resilience, sustainable and green economy, and smart governance and delivery. Each area is supported by sublayers with custom KPIs, allowing the lab to evaluate and optimise design performance.

What sets this framework apart is its ability to transcend traditional silos within the Architecture, Engineering and Construction (AEC) industry. By cross-referencing data from diverse thematic areas, the Biourbanism Lab addresses the complex interdependencies inherent in urban systems. For instance, by examining the interplay between economic and ecological criteria, the lab uncovers insights into ‘Ecologic-Economics’ – exploring how economic activities and ecological health are intertwined in urban environments.

1. Living Infrastructure Framework. Image showing different key areas and sub-themes evaluated through the framework. McGregor Coxall, 2024

2. Digital Approach. Set of steps to establish interrelationships between disparate datasets towards design task support. McGregor

Figure 3. Analytical and Categorical models generated by the Living Infrastructure Framework implementation. Note that analytical models generate a full 3D model thanks to LIDAR point cloud data. McGregor Coxall, 2024

Central to this process is translating multidisciplinary inputs into a common language: data. This approach empowers stakeholders from various backgrounds to collaborate effectively, linking non-design disciplines to design tasks through a parametric approach. By moving away from isolated, discipline-specific practices, the Living Infrastructure Framework fosters a highly complex and interconnected system that informs every stage of the design process.

The practical application of this process begins with data gathering, facilitated by the Living Infrastructure platform – an innovative in-house tool developed by the Biourbanism Lab. This platform aggregates data from various official and open-source datasets, including Ordnance Survey, Landsat 9 and DEFRA among others, integrating them into a unified model. However, the platform’s capabilities extend beyond data collection. It implements a sophisticated knowledge graph that establishes interconnections between data points based on the Living Infrastructure Framework. Each data point is categorised and weighted according to McGregor Coxall’s extensive project experience, ensuring the data reflects the nuanced realities of social, cultural and environmental contexts.

This curated data is then utilised in two models available to designers: a 3D analytical model that visualises the results of all analyses and a 2D categorical model that organises data according to the Living Infrastructure categories and subcategories. These models

enable designers to make informed decisions and establish a solid foundation for project development.

One of the most effective methodologies employed by McGregor Coxall is the Multiple Objective Evolutive Algorithm (MOEA). This advanced algorithmic approach optimises design scenarios based on project goals, stakeholder input and Living Infrastructure KPIs. By clearly defining project objectives and their relative importance, the MOEA generates design options that align with broader goals.

This holistic approach ensures that every design scenario is rooted in a deep understanding of the complex interrelationships within urban ecosystems. By leveraging the power of data and digital technologies, McGregor Coxall is charting a new path forward –one where cities and nature coexist in harmony and where urban development contributes to a healthier, more sustainable future for all.

Michael Cowdy is the UK Founder and Director of McGregor Coxall and a Fellow of the Landscape Institute.

Jorge Sainz de Aja Curbelo is the UK Biourbanism Lead at McGregor Coxall and holds a PhD in data-driven urban regeneration strategies.

With the implementation of Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) comes a significant opportunity for more data-driven approaches to design, as well as more collaboration on projects. Here, three perspectives on key technologies provide insight into how.

From Geographic Information Systems (GIS), to computer aided design (CAD), to Building Information Modelling (BIM) and beyond, digital technologies are becoming essential tools for landscape professionals to provide integrated services that help to boost biodiversity on projects and help nature recover.

In this series of perspectives from across the landscape sector we look at these technologies, as well as where

they overlap and interact, finding out how they can be incorporated into workflows and bring disciplines together collaboratively on projects.

The mapping capabilities of GIS enable the spatialisation of data, which forms the basis of any biodiversity or ecological assessment of a given project. Combined with the design functionality of CAD, this data can be incorporated into landscape designs which ensure the right planting is used in the right place to make best use of

the land, alongside other competing objectives and outcomes. By using BIM, designs can be visualised as 3D models that can track live data over time, which is fed back to practitioners to model design iterations and inform project maintenance. The possibilities are growing all the time.

With BNG providing the stimulus for more data-driven approaches to decision making, as well as more collaboration between disciplines on projects, how can technology help?

Over the years landscape architects and ecologists have been like wo tribes – one using computer aided design (CAD) to design, the other using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) for site management and spatial analysis. But with Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG), there is a real need to collaborate.

While an ecological survey will establish the current biodiversity baseline on a site, it will often be a landscape architect’s design that will define the biodiversity value post-development. A 2022 Landscape Institute policy briefing¹ suggested that, for landscape architects, BNG would mean liaising closely with project ecologists from inception, translating their recommendations into plans and designing sensitively to retain and enhance key existing habitats. It also recognised that the ‘accurate translation of habitat boundaries between GIS and CAD is vital to avoid frustration and delays’.

I’m not a CAD user, or a practising ecologist, or a landscape architect. I’m a GIS specialist and I love to collaborate, working daily alongside both ecologists and landscape architects. I wanted to better understand the issues both groups experience around GIS, CAD and BNG, so I reached out and spoke to both groups.

A number of factors contribute to the issues involved in integrating data from CAD to GIS, from there being so many CAD systems, each with their own proprietary functionality, to poor drafting

and layer management in CAD, which result in errors imported into GIS software, to the sheer number of disciplines that may have worked on a CAD file before it arrives with the ecologist. Here’s how to improve the workflow for better collaboration:

– Be aware that the main map projection used in the UK for BNG assessments is EPSG 27700: British National Grid, and ensure coordinates are set to metres before providing data to an ecologist.

– Remove page elements, including legends, unrequired layers and design revisions.

– Ensure good drawing practice and layer management to ensure data integrity.

– Discuss your needs with landscape architects and ask for unnecessary layers to be turned off.

– Be specific about the projection needed, setting coordinates to meters and that habitat area calculations require continuous polylines and closed polygons.

– Request data to be saved as ASCII format DXF, which will make it easier to import and work in GIS systems.

– Discuss UK habitat classifications, plant codes and pallets with the landscape architect to aid understanding and interpretation.

Matthew Davies is a GIS specialist and founder of Maplango.

QGIS BNG Assessment Project with CAD data loaded to the Proposed Habitat layer. Background map © OpenStreetMap

¹

2. Performing a

Urban Green utilises Geographic Information Systems (GIS) for data collection, data analysis and presentation, as a valuable tool to inform all aspects of site assessment across in-house teams including landscape, ecology and urban design.

Often, the initial baseline assessment consists of an ecological and biodiversity survey, undertaken in accordance with the UK Habitat Classification System (UKHAB). The ecology and Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) teams use an on-site GIS data collection survey system that is specifically tailored for UKHAB surveys and BNG metrics. Species lists and condition scores are then recorded within the system, accurately positioning and associating to their mapped habitats to inform the Biodiversity Metric¹ baseline data.

Once the on-site data has been collected it will be transferred through to GIS software. The data will then be processed and mapped on to the site’s topographical survey to map habitat data and tree surveys live in the field, supporting assessments and feeding into the landscape proposals.

Through close collaboration between the Landscape Design and BNG teams, the proposals are tested and refined to maximise the on-site opportunities available and explore ways to incorporate new or enhanced habitat types and landscape features.

¹ https://www.gov.uk/ guidance/biodiversitymetric-calculatethe-biodiversity-netgain-of-a-project-ordevelopment

² https://publications. naturalengland.org.uk/ publication/ 5846537451339776

This design information is produced in CAD to enable the habitat areas, linear features, blue infrastructure and other components to be measurable and quantifiable. These quantities are then transferred into the BNG metric calculator to show

both the pre- and post- development elements of the site and if the required minimum 10% net gain has been achieved.

The existing and proposed habitat maps will then be translated into an Urban Greening Factor² map which simplifies the UKHAB classifications. This simplified version can aid the end design of the projects, allowing for the best biodiversity net gain results.

BNG is still evolving. Local authorities and developers are still new to the processes and requirements and no two projects are the same, so a flexible approach is required.

The use of GIS technologies in particular aides this flexibility, furthering interdisciplinary collaboration through an efficient, accurate and comprehensible way of producing a BNG assessment. This is a key asset in the production of holistic, environmentally conscious schemes which are beneficial to both the local wildlife and the communities they serve.

Tim Calnan CMLI

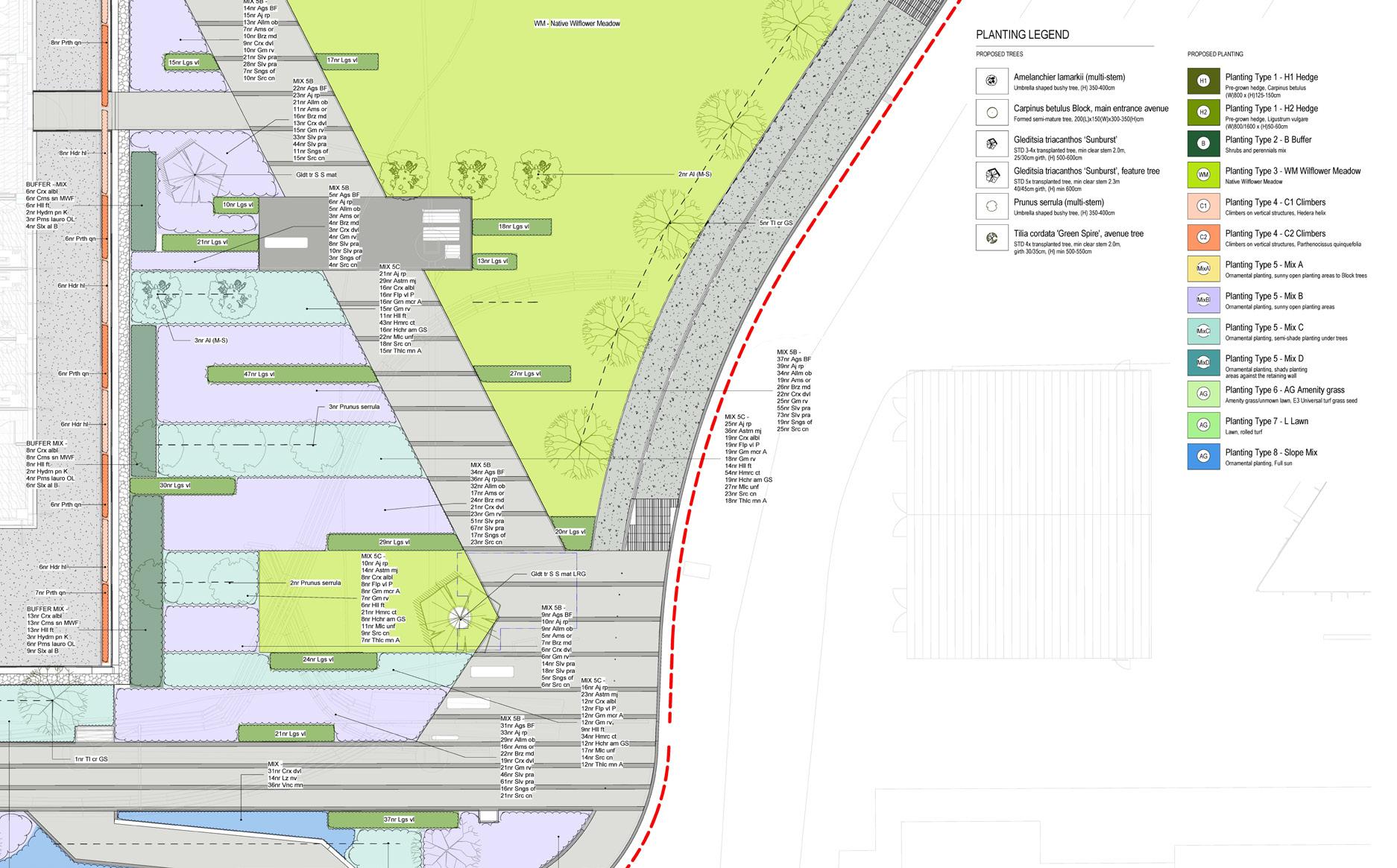

The University of Birmingham Molecular Sciences Building, completed in 2023, is an £80 million project including a landscape designed and delivered using Building Information Modelling (BIM).

The university gardens’ planting scheme was created using BIM to design single planting, area planting and the creation of planting mixes. Rather than having to manually define planting types, specification information and quantities, the project team was able to use a centralised, cloud-based platform to create and manage plants and mixes collaboratively throughout the design phases.

Importing directly from cloud-based planting libraries, the design team created palettes of single species and mixes that best reflected the specific requirements of the project, which incorporated shade, semi-shade, sun, slopes, buffers and retaining walls. The planting in the model was automatically populated with characteristics such as

height, form, spread, growth rate and ultimate height at maturity of each specimen. With any changes to the model immediately displayed in plan, section, elevation and schedule views, the team was able to test and evaluate their choices in real time as the design progressed.

Being able to view planting components in a 3D model enabled the team to consider the impact of trees above and beneath the ground, whether as a result of their canopies, growth, ultimate height and spread, shadow casting, tree pits and root balls. Used alongside other technologies, more opportunities open up, as design options can be used in conjunction with virtual or augmented reality technologies to provide users with an immersive 4D experience of the designs.

Models such as this can also be used in Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) assessments, helping practitioners to map out different potential habitat scenarios and measure design iterations against the anticipated net gain throughout the design process. Combined with Geographic Information System (GIS) data, practitioners can model project change over time and once built, the model can even become a digital twin, modelling live, real-time data and informing ongoing management and maintenance.

From plant selection to real-time iteration, tools for design automation, review, modification and visualisation are becoming essential for better collaboration, coordination and efficiency.

Tim Calnan CMLI is founder of Cloudscapes.

Landscape and Carbon Steering Group member

Sam Bailey CMLI takes a broad definition of technology to look at how new innovation can help to reduce carbon in landscape projects.

Sam Bailey CMLI

‘Technology: the application of scientific knowledge for practical purposes, especially in industry.’1 Taking this broad definition of technology, which could span the digital, mechanical, material or biological and harnessing it to take a perspective from today, one might expect that the rapid advancement of technology this millennium and the explosion of knowledge spawned by the internet, would have spurred a great amount of progress for its use in sustainable development. However, construction can be a slow beast to adapt and the landscape sector remains engrained in traditional construction methods used for many decades. In contrast, buildings and all the elements they are made of, have benefited from technological advancements, including Modern Methods of Construction (MMC) and advances in renewable technology which are making them cleaner and more efficient.

The slow uptake of technological improvements in our industry may be attributed to the inherent perception that landscapes are simply nice, green and environmentally friendly. However, the hidden carbon costs of these projects often go unnoticed. The carbon impact of landscape development is a fraction of building and structural elements, but the carbon reductions that can be made, with relative ease, are significant. Understanding that impact is key and easily comparable knowledge will help bring that into decision-making.

The consideration of carbon in projects presents an important dilemma: How do we balance the creation of biodiverse landscapes, active travel and neighbourhood regeneration while ensuring that the materials and methods we employ to create them do not impose an unsustainable environmental