8 minute read

The transformation of Medellín

INTERNATIONAL SHOWCASE, by Jota Samper and Carlos Escobar

Environmental remediation and community development is having a huge impact on the informal settlements of Medellin in Colombia.

Medellin is the secondlargest city in Colombia; it was the centre of agrarian production in the early part of the 20th century with the boom in coffee production, then transitioned to the manufacturing of goods such as textiles.

As with many Latin American cities, Medellin received a large influx of population from the rural areas in the late part of the 20th century generating a massive urban expansion. However, the collapse of industries resulted in a lack of opportunities for employment for those arriving at the city, the lack of jobs and affordable housing opportunities propelled these poor arriving populations to create informal settlements on the edges of the city. Most of them are in high slopes of the mountains or in flood banks of the hundreds of creeks that surround the valley. The combination of the hazardous condition of this geography and the vulnerability of these populations creates high levels of environmental insecurity. The frequent rains and slopes soils composition create a risk to landslides or floods and endanger the lives of the thousands of informal dwellers of the city. Just in 1987, a landslide in the neighbourhood of Villatina took the life of 500 inhabitants. 1

In the 1980s and 90s, Medellin experienced the most difficult moments in its recent history, high unemployment rates, violence and the continuous expansion of informal settlements. With the collapse of industries in the city, the illicit drug market emerged.

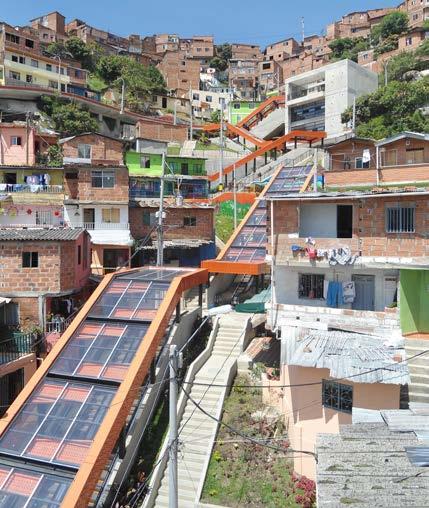

Escalators. Before and after.

© Jota Samper, Carlos Escobar

The informal neighbourhoods became areas ripe for recruitment for the violent efforts of drug cartels and for the hiding of illegal groups that were fighting the Government in the long, nondeclared civil war in Colombia. The low institutional presence and the lack of public investment, high unemployment rate, and the high levels of poverty turned the informal settlements of the city into favourable territories to house illegal groups.

The resurgence of the city over the last decade is the result of the collective efforts of initiatives of a social, academic, cultural and institutional nature. These include the Consajeria para la Paz (Peace Council), the municipal investments in public infrastructure like the METRO system, and the local communitarian organisations’ centres in the hundreds of informal settlements of the city. In response to the failure of military interventions to improve security in informal areas, the city made large investments in public works, such as cable cars, educational and cultural facilities, and urban projects in the poorest of the areas. These projects generated significant urban, social and cultural improvements in these neighbourhoods.

Childhood Park and tourists at Graffitour.

© Valeria Henao

The continued municipal effort maintained over several public administrations is known today as “the transformation of Medellín’’. The primary strategy was the use of physical urban projects to transform the city socially and physically. The most significant of those infrastructure strategies are the Integrated Urban projects (known in Spanish as PUI – Proyectos Urbanos Integrales). These PUI projects bring together various physical initiatives: libraries, schools, transportation, public space, housing, and environmental remediation. They built them in a short period throughout the most marginalised areas of the city. The interventions cover two critical problems: (1) social inequality, what public officials called the “social debt” of the city to the poor, and (2) violence, which has deep roots across all social classes . The value of the Medellin upgrading effort is significant since the state had not invested in many of these neighbourhoods in as much as sixty years.

The PUI comprises three areas of intervention. Firstly, inter-institutional coordination via the Empresa de Desarrollo Urbano (EDU), which dovetailed the different Municipal offices. Secondly, community participation through public meetings. Among all Latin American urban upgrading projects, the PUI stands out as an example of how to engage with marginalised communities. The PUI included a wide variety of projects that included public space, environmental remediation, housing, and transportation. The PUI projects are one of the most important contributions to the physical landscape of Medellín. The four PUIs up to today have become a model for dealing with informal settlements, and the project sites are attractions both for scholars and practitioners interested in dealing with issues of urban informality, as well as to tourists who come to see these unique spaces.

PUI of Comuna 13

The Comuna 13th, located on the western side of the city of Medellín, has an area of 450 hectares and a population of 145,000 inhabitants 2 Nearly 60% of this territory presents informal urbanisation and this has resulted in deterioration of natural resources, reduced mobility, absence of public spaces and facilities, little institutional coverage and poverty 3 . However, the most distinct feature of this district has been violence. Between 2003 and 2012, more than 1,200 murders occurred, and in 2010 the homicide rate reached 172.5 violent deaths per 100,000 inhabitants. These circumstances made Comuna 13 one of the most segregated areas in the city. The combination of lack of infrastructure and insecurity was the motivating factor for the city to implement the PUI – Comuna 13th between 2007 and 2012, to improve the district’s conditions.

The PUI is a strategy that simultaneously tackles the physical, social, and institutional problems of the district with actions in three areas:

1. Physical space – with increased public areas to improve human and social interaction, new facilities to increase the coverage of programs and public policies, and the improvement of pedestrian and vehicular mobility to facilitate social integration and free access to residents and resources.

2. Social initiatives: training of community organisations and the participation of locals in the conception, development, and construction of projects. The social work improved credibility in the Government and reduced indifference and social resistance towards public initiatives.

3. Institutional coordination: synchronizing the work of public institutions, to optimise their technical resources through coordinated action. The work of state institutions in these neighbourhoods made city management more efficient and improved the image of the state with the local population.

The PUI of Comuna 13, with an investment of 35 million dollars over 5 years, included eight parks, four community centres, two sports facilities, five vehicular roads and two pedestrian trails. A critical project was the construction of a system of public escalators to solve mobility in the high sloped areas of the district. The PUI encompassed more than 110,000 square metres and created 2,341 jobs whilst the EDU carried out 13,965 public engagement activities with a total participation of 171,491 residents 4 . The PUI reduced risk conditions in steep slopes susceptible to landslides, a place vulnerable to the effects of climate change. These projects were designed in compliance with building and safety codes, including earthquake resistance analysis. In this context, structural elements such as retaining walls, aqueducts and sewer systems were used to stabilise the soils, avoid further landslides and reduce the vulnerability of homes located in these neighbourhoods due to extreme weather.

In particular, the new spatial conditions of the PUI generated opportunities for cultural and economic development. Fundamental in such development is the way the local community appropriated some projects such as the escalators. In addition to providing solutions for mobility, this project has been a catalyst for the social and economic development of the community. Since the beginning, the escalator project has led to the arrival of visitors from all over the world, initially, those interested in knowing about its application in the context of Informal settlements. Later on, tourists have been interested in learning about new expressions of “urban art” strongly embraced by the population which the escalators have made more visible. The constant arrival of visitors to this place and the economic resources they bring with them have become an opportunity for economic growth for these impoverished communities. Local entrepreneurs capture these new resources through small shops like the sale of souvenirs, typical foods or drinks and through a new offer of specialised cultural and artistic services called the Graffitour. During these, visitors learn through urban art, the history of resilience and hope of the Comuna 13 residents. The visits are organised and guided by local youth groups, who have converted the new plazas, trails, retaining walls and façades around the escalators, into art galleries and meeting places. There, groups of local artists converge through murals, music, and dance, the stories of poverty, violence, physical transformation, and social rebirth that lived in this area during the last decades.

PUI Comuna 13, Master Plan.

© Carlos Escobar

Local artist group and tourists.

© Jota Samper, Carlos Escobar

Square, Graffitour’s area.

© Jota Samper, Carlos Escobar

The critical lesson from Medellin is about the synergy between state-risk infrastructure projects and communityled cultural projects. These cultural projects, many of which started as a response of residents to the violence in their communities, used the project’s success to export the positive values upheld by the community. It is through the synergy of the success of urban projects and the uniqueness of the community cultural projects that a new hybrid was created that catapulted both efforts to a new space in which state, local community organisations and foreigners, in the form of tourists, all help in the betterment of the community.

Jota Samper is an Assistant Professor at the Environmental Design Program at the University of Colorado Boulder. His work concentrates on sustainable urban growth and at the intersection between urban informality and violent urban conflict. Carlos Escobar is a Consultant from the Housing and Urban Development División at the InterAmerican Development Bank. His expertise as Coordinator of Urbanism and Architecture for the Integrated Urban Project at La Comuna 13 in Medellín, has led him to participate in different academic and urban initiatives in Central América and the Caribbean.