6 minute read

Underground Urbanism Stitching together the layers of our urban landscapes

Landscaped spaces are often placed above buried infrastructure. Elizabeth Reynolds asks if landscape practice can become an integral part of the design process.

As our cities grow up, out and down, it is time we better understood how the different layers of these complex urban environments relate to one another.

Landscape architects have an important role to play in stitching cities together in a manner that optimises land while also ensuring that the journey of a pedestrian through a city is a coherent and enjoyable one. The notion of multi-level living is something which as humans we have had to adapt to. In his book Vertical, Stephen Graham asks difficult questions about the potential consequences for people living in dense, multi layered cities. For example, do citizens have a right to identify and experience natural ground level? Although people tend to experience underground places as interiors, cities such as Hong Kong and Singapore are developing more underground pedestrian walkways, and the same care should be taken to design these as coherent sequences within longer journeys as with external spaces.

Beyond the human element, it is worth also considering the natural systems disrupted by construction of the infrastructure needs of cities. Earth extracted for railway networks, utility pipes and basements is relocated and used, for example, to contour golf courses or reclaim land from the sea. The properties of that soil are therefore lost from the city, and the water previously held within it either extracted or diverted. What physical space and natural capital remains beneath our cities, and how can we balance the competing demands and consequences associated with urban development?

Overcoming urban severance

Since Le Corbusier’s vision of the Radiant City in the 1920s, a desire to create fast flowing elevated roads has scarred many cities. At street level, even contemporary road and rail projects designed to improve access and over long distances tend to create severance that impedes local connectivity. When considering the removal or scaling back of major road infrastructure, careful consideration should be given as to whether it is most appropriate to make lateral or vertical changes, such as new (deep) tunnels, shallow (cut and cover) decks or (elevated) bridges.

Lowline Lab – a testbed for the world’s first underground park by Raad Studio and Mathews Nielsen.

© Creative Commons (JCBergland, 15 March, 2016)

These decisions will largely depend on the surrounding street pattern and built form; subsurface constraints (such as utility diversions or ground conditions that could increase construction costs) and wider policy objectives. Although sinking road traffic into tunnels can create opportunities for landscaped public open space, it is important that these initiatives are taken as part of holistic measures to reduce car use, in order to ensure that air quality and other traffic impacts are not simply displaced.

Paul Lecroart, of the Planning Agency for the Paris Metropolitan Region (IAU), says that converting stretches of highways into multi-use boulevards and public spaces may open up new avenues for rethinking our cities in terms of liveability, mobility and resilience (Lecroart, P (2018). Lecroart has researched over 20 case studies of highways being converted to urban boulevards and linear parks including the Cheonggyecheon River in Seoul where a highway previously carrying 168,000 cars a day was removed and the previously culverted river restored. Traffic has significantly continued to reduce and in summer temperatures are now 5°C lower than on other arterial roads. In Boston, although the Big Dig project became a byword for mismanagement, it is an improvement to the amenity and landscape of Boston.

From its construction in 1959, an elevated section of the Interstate 93 highway divided downtown Boston from its waterfront, significantly impacting the quality of the urban environment. The eventual diversion of the elevated highway into a tunnel has enabled creation of the Rose Kennedy Greenway. A series of five interconnected parks stretch across 2.4km and are maintained by the Rose Kennedy Greenway Conservancy who describe the space as ‘a roof garden atop a highway tunnel’ (RFKGC, 2017). The parks have transformed the character of Boston and opened up new opportunities for the surrounding communities. Closer to home, Barcelona’s Ronda del Mig (by Jordi Henrich & Olga Tarraso) is also a good example of building over a dual carriageway to form a public park.

Multifunctional and adaptable infrastructure

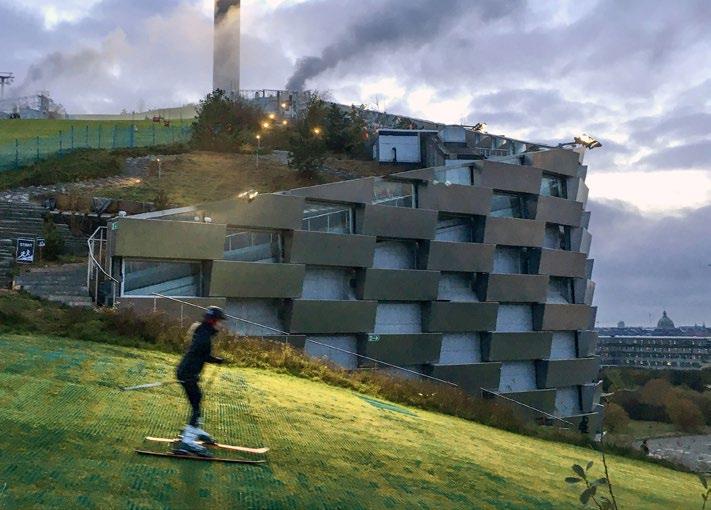

Coppenhill – an urban ski slope above a biomass waste to energy plant in Copenhagen, Denmark designed by Bjarke Ingles Group with landscape by SLA.

© Creative Commons (Kallerna, 04 November 2019)

The above examples tend to place landscaped spaces above the buried infrastructure, but can landscape architecture move from perhaps being part of the lipstick on an infrastructure gorilla, to a more integral part of the design process?

Copenhill is the world’s first ski slope on a waste recycling plant. The Amager Bakke as it is formally known, is a fully operational biomass waste to energy plant in Copenhagen, Denmark. Designed by architects Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) for Amager Ressource Centre, it is able to convert 400,000 tons of waste each year – enough to provide heat for 150,000 households and low-carbon electricity for 550,000 people. Working with Landscape Architects SLA, this has become far more than just a functional, single purpose structure, with BIG designing the building to incorporate a ski slope, hiking trail, and climbing wall. Reaching a peak of 85m, this manmade mountain has 10 different hiking and running routes landscaped with rocks, grasses, over 7,000 bushes and 130 trees.

Bjarke Ingels (Architectural Digest, 2019)

On the other side of the Atlantic in Manhattan, an entirely new form of excavated, rather than extruded, landscape is proposed. Located in a former tram depot, the Lowline takes a radical approach to the creation of new and much needed public open space in a dense urban environment.

James Ramsey, Founder of the Lowline and RAAD design studio.’ (Lowline, 2018)

The Lowline Lab was created to test the viability of the park and to help children learn about science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics (STEAM). The Lowline Lab comprised a 464 sqm installation of the plants and lighting that could feature in the Lowline park. Some 3,000 plants including mosses, herbs, vegetables and tropical fruits were grown beneath lighting prototypes that were designed and installed by RAAD and a Korean technology company, Sunportal, in a landscape designed by Signe Nielsen of Mathews Nielsen and built by John Mini Distinctive Landscapes.

As these case studies suggest, there is a role for ecologists and landscape architects to bring their understanding of urban ecosystems and interactions between man and nature to all layers of the city, from the highest spaces to the deepest places.

Underground Urbanism is published by Routledge and is available in bookshops and from the publisher: www.routledge.com

Elizabeth Reynolds MRTPI is a director of Urben Limited