Pioneering the park of the future Community engagement, climate emergency and inclusivity.

landscapeinstitute.org Autumn 2023 £15.00

landscapeinstitute.org Autumn 2023

£15.00

Front cover and inside front cover images: The Grand Entrance (Front cover) to Birkenhead Park and the exit (Inside front cover).

Designed by Lewis Hornblower, with amendments by Joseph Paxton. © Robin Maryon

PUBLISHER

Darkhorse Design Ltd

T (0)20 7323 1931 darkhorsedesign.co.uk tim@darkhorsedesign.co.uk

EDITORIAL ADVISORY PANEL

Saira Ali Team Leader, Landscape, Design and Conservation, City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council

Stella Bland Head of Communications, LDA Design

Marc Tomes CMLI, Director, Allen Scott Landscape Architecture

Sandeep Menon, Landscape architect and university tutor, Manchester Metropolitan University

Peter Sheard CMLI, Landscape architect

Jaideep Warya CMLI, Landscape architect, Allies and Morrison

LANDSCAPE INSTITUTE

Editor: Paul Lincoln paul.lincoln@landscapeinstitute.org

Copy Editor: Jill White

Proof Reader: Johanna Robinson

President-elect and Acting President: Carolin Göhler

Acting CEO: Robert Hughes Head of Marketing, Communications and Events: Neelam Sheemar

Landscapeinstitute.org

@talklandscape landscapeinstitute landscapeinstituteUK

Pioneering the park of the future

The gates to Birkenhead Park have been open for more than 150 years. In its application to become a World Heritage site, the government has called it, ‘a blueprint for municipal planning that has influenced town and city parks across the world’. However, as Karen Fitzsimon asks in her feature on Birkenhead, ‘Do large parks like these tie us to a public park concept that is no longer relevant to current needs?’

Responses to this provocation can be found throughout this issue: in Rajasthan, where improvements at Udaan Park have recently transformed an underused, lakeside park into a safe public space and in three parks in Dubai, all of which demonstrate approaches to irrigation and planting that are of immense relevance to the UK.

The important work in Glasgow is reinforced by research at Leeds University, which has led to new guidelines designed to make parks and green spaces safer for women and girls across the UK.

Although Covid briefly put parks on the national map, the focus on the health benefits of green space is no longer a high-profile issue. However, the relationship between park management and design, backed up by funding which recognises their significance, is crucial in creating parks that are fit for the future.

At the heart of every park, from Birkenhead to Udaan, is the relationship between design and management. This edition examines these through the lens of community engagement, climate emergency and inclusivity.

Landscape is available to members both online and in print. If you want to receive a print version, please register your interest online at: my.landscapeinstitute.org

Landscape is printed on paper sourced from EMAS (Environmental Management and Audit Scheme) certified manufacturers to ensure responsible printing.

The views expressed in this journal are those of the contributors and advertisers and not necessarily those of the Landscape Institute, Darkhorse or the Editorial Advisory Panel. While every effort has been made to check the accuracy and validity of the information given in this publication, neither the Institute nor the Publisher accept any responsibility for the subsequent use of this information, for any errors or omissions that it may contain, or for any misunderstandings arising from it.

Landscape is the official journal of the Landscape Institute, ISSN: 1742–2914

© 2023 Landscape Institute. Landscape is published four times a year by Darkhorse Design.

Aberdeen’s Union Terrace Gardens has defied commercial development and brought a much-contested site back to life. In Tottenham, extensive community consultation is leading to the creation of a brand-new park for a fast-growing part of the capital.

Glasgow City Council is putting women at the heart of planning. The council has made Glasgow the UK’s first feminist city, noting that ‘in order to create public spaces that are safe and inclusive for women, ...it is fundamental that women are central to all aspects of planning, public realm design, policy development and budgets’.

What we are now witnessing is the start of a fascinating process. For inclusion on the World Heritage List, a site like Birkenhead Park must be of ‘outstanding universal value’. The debate on how we interpret this, and nurture a dynamic public park concept that offers value to both current and future needs, is just beginning.

Paul Lincoln Editor

WELCOME

© Robin Maryon

3

Print or online?

Contents 4 Exploring the influence of Birkenhead Park 6 Pioneering the park A new park for Udaipur, India 14 Udaan Park Parks regeneration in Aberdeen 34 Reclaiming the Gardens A new park signals a greener future in North London 30 Tottenham Hale Irrigation, planting and parks in the Middle East Lessons for a changing climate 24 FEATURES How the Future Parks Accelerator programme is changing local authority thinking More than the sum of our parks 19 POLICY 38 Glasgow Implementing a feminist planning policy RESEARCH Realising the potential of landscape 45 Active travel 42 Sheffield The politics of street trees revisited

Carolin Göhler becomes President-elect 62 A champion for landscape architecture 67 Green Infrastructure Partnership New assessors 69 TMLI LI LIFE Squaring the circle of sustainability A change in the landscape 55 Ecocity World Summit 60 Venice Biennale REVIEWS TECHNICAL GUIDELINES 49 The Pathfinder tool A technical evaluation 52 Park design and management Improving safety for women and girls 5

Pioneering the park

‘Without Birkenhead Park, there would be no Central Park and without Central Park, there would be no New York City’. But how much of this legacy remains relevant for the designers of the climateresilient park for the 21st century?

FEATURE

1. Central Park –rocky outcrop & skyscrapers.

© Karen Fitzsimon

6

1 https://www.gov. uk/government/ news/seven-sitesconfirmed-in-therunning-for-unescoworld-heritage-status

2 It is on the Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest.

3 https://whc.unesco. org/en/criteria/

In April 2023 the UK government’s Department for Culture, Media and Sport announced that Birkenhead Park, ‘a pioneering project to bring greenery to urban environments’ providing ‘a blueprint for municipal planning that has influenced town and city parks across the world’, would be added to its Tentative List for consideration as a World Heritage site.¹ Inclusion means the government will support Wirral Council in the development of a bid to UNESCO for the prestigious status. Currently the UK has 33 World Heritage Sites, none of which are publicly commissioned civic parks, making Birkenhead Park the first, should the application succeed.

Birkenhead Park, near Liverpool, is ‘pioneering’ because it was globally the first free-to-enter park commissioned by a municipality, paid

for with public funds. It commenced an urban-park movement that had international impact, including on the design of Central Park in New York City, possibly the world’s most famous metropolitan park.

Of course, parks have been around for centuries, the earliest ones adapted from royal or private estates, or created through philanthropy, but they were not universally accessible. For example, in 1811 The Regent’s Park, London (Grade I listed) was designed by John Nash (1752–1835) under royal commission.² However, initially it was accessible just to residents of villas built around the park and only in 1835 did a section open to the public. In 1840 Derby Arboretum (Grade II*) was opened, commissioned privately by benefactor Joseph Strutt and designed by influential Scottish author and designer JC Loudon (1783–1843), but was free to enter only on a limited basis. Victoria Park (Grade II*), London, was the most publicly accessible large park of the period. However, it was a Royal Park, having been commissioned by Queen Victoria, albeit following public petition, and paid for by Royal Grant. Designed initially by James Pennethorne (1801–71), of the Crown Estate, with early modifications by

others, the 215-acre site opened to the public in 1845, transferring to municipal ownership in 1887.

For inclusion on the World Heritage List a site must be of ‘outstanding universal value’ and satisfy at least one of ten criteria.³ Birkenhead Park’s management team considers the site satisfies three of these: it represents ‘a masterpiece of human creative genius; it exhibits, ‘an important interchange of human values, over a span of time or within a cultural area of the world, on developments in architecture or technology, monumental arts, town-planning or landscape design’; and it is ‘an outstanding example of a type of building, architectural or technological ensemble or landscape which illustrates (a) significant stage(s) in human history’. Birkenhead has rightly high hopes for its bid, but it has much to do to develop a successful nomination, a process that can take several years.

Given such developments, it seems timely to gain an historical perspective on the impact of two major mid-19-century parks that have broadly formed our perception of what an urban public park should be, at least until recent times. This article examines Birkenhead Park and Central

2. Nineteenthcentury map of Birkenhead Park.

© The Williamson Art Gallery & Museum, Birkenhead

Karen Fitzsimon

FEATURE

7

2.

Park, to consider common themes in terms of their commissioning, design and influence over the past 180 years

Birkenhead Park

From as early as 1822 Loudon had campaigned for the creation of universal public parks as metaphorical ‘breathing places’. This push grew from public-health concerns within the rapidly expanding urban areas, when disease was thought to have been spread by ‘miasmas’ – bad air

emanating from decomposing organic waste and contaminated water. Although the mechanism of air pollution or its management were not then understood, there was a sense that green spaces could help. Additionally, parks could offer the city-dweller an antidote to an increasingly industrial lifestyle and concurrently improve moral behaviour by providing a distraction to publichouse culture. They could also advance local land values, especially when

aspirational villas were part of the layout design. The case for planned public parks was reinforced by the 1833 Select Committee on Public Walks, whose remit included consideration of ‘the best means of securing open spaces in the immediate vicinity of populous towns, as public walks calculated to promote the health and comfort of the inhabitants’.⁴

Birkenhead, which sits at the north end of the Wirral Peninsula in northwest England, has 12-century

4

3. Nineteenthcentury Newman engraving showing the Swiss Bridge, Birkenhead Park.

© The Williamson Art Gallery & Museum, Birkenhead

4. Contemporary image of the Swiss Bridge.

© Robin Maryon

parliament.uk/pa/ cm201617/cmselect/ cmcomloc/45/4504. htm FEATURE

https://publications.

3.

8

4.

monastic foundations. Water and transport were key to its development – initially the monks operated a ferry across the Mersey to Liverpool to deliver produce to market. It remained a small settlement until the early 19-century when, like elsewhere, steamboats replaced rowed vessels and the town expanded. In 1833, following the Select Committee, Birkenhead Improvement Commission was enacted to provide municipal services. Soon they received requests to provide a public park. This was made possible through the 1843 Birkenhead Extension Act of Parliament, which permitted the town to use public money to create a civic park.

The commissioners promptly borrowed £60,000 from the government and purchased poorquality, low-lying marshy land on the town’s edge. An area of 125 acres was allocated for the park and a further 60, around the periphery, sold for private houses to bolster funds. Keen to maintain control of the overall aesthetic, the Commission mandated adherence to their own housing style guide.

Joseph Paxton (1803–65), eminent

horticulturist, author and head gardener at Chatsworth Estate, whose recent work at Prince’s Park, Liverpool (1842–44) for philanthropic industrialist Richard Vaughan Yates had been admired, was appointed directly by the Commission to design Birkenhead Park. Paxton laid the site out between 1843 and 1847 for a fee of £800. His design concept was to bring a piece of countryside into the urban setting. A combination of open meadows,

naturalistic woodland, tree clumps, rocky gorges and two sinuous ribbon lakes with islands were created, all of which afforded a comfortable combination of wide views and intimate spaces. Paxton drained the site and used excavated lake spoil to create topography, in places raising it ten metres, on an otherwise flat site. The resultant landform concealed the town and heightened the sense of rus in urbe. The work was supervised by Edward Kemp (1817–1891), a protégé from Chatsworth, who later established himself as a successful landscape designer and author.

Traffic segregation was an innovative element – the park was connected to the town east–west by Ashville Road, while a peripheral carriage route circumnavigated the site, beyond which were the villas set in private gardens. The only part of Paxton’s design to accommodate flower gardens was the transitional zone between villas and park.

Perambulation was until this time the traditional activity undertaken in parks, and so a series of winding footpaths moved people through the site. However, in yet another innovation he extended the scope of activity by creating large areas of grassland for sports, principally cricket and archery. Architectural elements were expected by the client and Paxton employed Liverpool architect Lewis Hornblower (1823–1879) – who also co-designed Sefton Park – to design structures

FEATURE

5. Contemporary image of the Rustic Bridge, Birkenhead Park.

© Robin Maryon

6. Contemporary city living, Central Park.

© Karen Fitzsimon

6.

9

5.

FEATURE

7. Map of Central Park, New York City, 1868. © wiki commons

8. Bethesda Terrace, Central Park, late 1880s. © wiki commons

8.

10

7.

including a tripled-arched grand entrance (which Paxton considered too conspicuous, but was nonetheless approved by the town), lodges, bridges, boathouse and an ornate Swiss bridge.

Birkenhead Park was completed in autumn 1846 at an estimated cost of £227,000. It was a milestone in the British urban-park movement and was enthusiastically received when it opened in spring 1847. Today, most of Paxton’s original design still exists and the now Grade I listed park receives around two million visitors a year, which undoubtedly will increase substantially should it receive World Heritage status.

Central Park

In 1850 Fredrick Law Olmsted (1822–1903), an American gentleman farmer, spent six months travelling Europe to study agricultural systems. He was in England during May and was charmed by the beauty of the neat countryside, including that of his ancestral home, Olmsted Hall, Cambridgeshire. He went to see the

layout of Birkenhead new-town, where by chance a shopkeeper urged him to visit the town’s new park. It was a serendipitous suggestion that changed the course of Olmsted’s life, and that of the urban-park movement.

While critical of the ostentatious grand entrance and elaborate flower beds, Olmsted was enthralled by everything else and ‘the manner in which art had been employed to obtain from nature so much beauty’.⁵

He admired the rich planting of trees and shrubs and the sheep-grazed meadows, the topography, the successful drainage system, segregated traffic routes and the cricket. But what struck him most was that the park was ‘enjoyed ... equally by all classes’ and he dubbed it ‘The People’s Garden’.⁶ Olmsted published his findings in several papers and became a champion for universal public parks.

Meanwhile, New York City was rapidly expanding and overcrowded, yet its 1811 grid layout provided no large park. There was a danger that all land could be built upon before one

was created. By 1853 the city, under pressure from advocates, started to acquire land for one. They already owned two large Midtown reservoirs (constructed in the wake of an 1832 cholera epidemic), and for economic expediency, and following a suggestion by influential landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing (1815–52), they decided to build the park around the reservoirs. This was legally enacted by the Central Park Act 1853. Commissioners were appointed to raise funds and acquire the remaining land. The creation of the park was considered part of the city’s critical public-health infrastructure as ‘lungs of the city’. The 843-acre site on Manhattan Island was mostly rocky and swampy. But it wasn’t totally inhospitable – a community of home-owning African-Americans and immigrants lived in an area called Seneca Village, where they had established small gardens and woods. In an act of social cleansing, they were relocated to facilitate the park’s construction.⁷

In 1857, Olmstead, by then a

5 FL Olmsted, ‘The People’s Park at Birkenhead’, in Fredrick Law Olmstead Essential Texts, ed. Robert Twombly (New York: WW Norton & Co, 2010), 42.

6 Ibid., 43.

11

7 ‘The creation of Central Park’, Central Park Conservancy, accessed May 16, 2023, https://www. centralparknyc.org/ articles/senecavillage.

successful reporter on matters of agriculture and social reform, was appointed Central Park Superintendent to oversee its development. A year later the commissioners held a design competition. Paxton’s apprentice Kemp was purportedly a judge. Thirty-three entries were received including ‘The Greensward Plan of Central Park’ from Olmsted and Calvert Vaux (1824–95). Vaux, a British architect, had moved from England to NYC in 1850 to work for Andrew Jackson Downing, soon becoming partner. Downing’s accidental death in 1852 left Vaux running the practice and, in tribute to his former colleague who had the original vision for Central Park, and probably his own advancement, invited Olmsted to partner in a submission. They produced 12 illustrated boards, printed text, construction details and cost

estimates.⁸ Despite Olmsted not having previously designed, let alone built, a landscape, they won and received the $2,000 prize. It was an enormous commission for a complex site. Construction occurred in two phases, 1858–63 and 1865–78, and cost $14 million.

The ‘Greensward’ concept offered city-dwellers an experience of countryside and nature, as Vaux said: ‘Nature first and second and third –architecture after a while’.⁹ OlmstedVaux’s design pivoted around the centrally placed reservoirs. They anticipated that the city would grow enormously around the park and responded with a novel traffic management system: four sunken transverse roads for non-park users, screened to the sides by planting, with green bridges above for park users; serpentine carriage drives within the

park as well as a complex undulating footpath and bridleway network, all offering scenic views. A thick boundary of trees framed the park within which sinuous lakes, meadows, woodlands, sports areas and playgrounds were carved, offering a variety of spaces – the curvaceous forms of which provided urbanites with contrast to the unrelenting rectilinear city grid. Timber structures, such as summerhouses and pergolas, enhanced the rustic ambiance. As at Birkenhead, the designers eschewed formality; however, the commissioners’ civic pride required some – and so an asymmetrically placed tree-lined Mall led to the Bethesda Terrace with fountain and arcade. Elsewhere ornamental arches and bridges abounded, plus some ornamental buildings.

Olmstead acknowledged the

FEATURE

9. The Ramble Winding Rocky Steps, Central Park. © Karen Fitzsimon

10. Bethseda Fountain, Central Park.

Designed by Emma Stebbins in 1868. Stebbins was the first woman to receive a commission for a major work of art in NYC. The fountain commemorates the 1842 supply of fresh water to the city. © Karen Fitzsimon

11. Roman Boathouse, Birkenhead Park. © Robin Maryon

12. Gardeners at work in Birkenhead Park. © Robin Maryon

10.

12.

11.

9.

8 Morrison H Heckscher, ‘Creating Central Park’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Winter (2008): 26–27.

12

9 Morrison H Heckscher, ‘Creating Central Park’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Winter (2008): 28.

12 https://www.gov. uk/government/ publications/greensocial-prescribingperceptionsamong-cliniciansand-the-public/ exploringperceptions-of-greensocial-prescribingamong-cliniciansand-the-public.

importance of Central Park ‘as the first real park made in this country – a democratic development of the highest significance … the primary purpose is to provide the best practical means of healthful recreation for the inhabitants of all classes’.10 The Olmsted-Vaux design is mostly intact and the park, now a designated National Historic Landscape, is on the US government’s Tentative List for World Heritage status. Managed by the Central Park Conservancy on behalf of the city since 1980, the site continues to undergo restoration and adaptation to accommodate its annual 42 million visitors. Acknowledging the important link between Birkenhead and Central Park, Doug Blonsky, former president and CEO of the Conservancy, commented in 2013 that ‘without Birkenhead Park, there would be no Central Park and without Central Park, there would be no New York City’.11 Quite a thought.

The relevance of large public parks Having developed from a desire to improve public health, by the close of the 19-century the need for free public parks was considered an urban-form necessity, with Birkenhead and Central Park the launchpads of their respective national city-parks movements. Local and national political leadership and ambition was crucial to their creation, and artistic and technical vision by the designers was essential to their execution and enduring success. The projects redirected Paxton’s and Olmsted’s own careers in the nascent profession of landscape architecture and established our practice as one founded on open-space planning. But do large parks like these tie us to a public park concept that is no longer relevant to current needs? I don’t believe it does – yes, we now expect more social engagement in their development, but they continue to contribute to city life – not just to health and wellbeing, so ably demonstrated during the Covid-19 pandemic, where they diluted crowds so that smaller parks were not overwhelmed, but also for their utility in contributing to green infrastructure and its essential role in combating climate change – stormwater and air

pollution management, biodiversity, air cooling, etc. The relative informality and simplicity of planting, predominantly trees and meadows, continues to be a touchstone with nature and appeals to the contemporary user, while simultaneously assisting diminishing park maintenance budgets, being less onerous than more fussy planting. The concept of segregated traffic is as relevant now as it was in the past, despite vehicles changing. Popular sports might differ but grass pitches are still required. Large parks modelled on these heritage sites complement smaller city spaces and should be

viewed as part of a linked greenway system and, given the rise in green ‘social prescriptions’, be considered complementary to, and as essential as, the National Health Service.12

Karen Fitzsimon is a chartered landscape architect, historian and horticulturist. She researches, writes and lectures about British landscape architecture, is a visiting lecturer at the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL and is also an experienced urban food-grower.

FEATURE

13. Strawberry Fields, Central Park.

© Karen Fitzsimon

13

14. Bow Bridge, Central Park, by British designers Calvert Vaux and Jacob Wray Mould. Constructed 1862. © Karen Fitzsimon

14.

13.

10 Letter to John Olmsted, January 14, 1858, Frederick Law Olmsted Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

11 Doug Blonsky, former President & CEO of the Central Park Conservancy.

Udaan Park: the seed of a million trees for Udaipur

The World Health Organization recommends a minimum green cover standard of 9m² per capita for cities; Udaipur in Rajasthan offers just 2m² per person. This park seeks to redress the balance.

FEATURE 1. All images are of Udaan Park. © Ankit Jain 14

Ananya Singhal

There is no bigger adversity facing humankind today than the combined environmental challenges of global warming, biodiversity loss and waste. This is why Studio Saar’s approach to architecture is underpinned by the ambition to create sustainable solutions for society and the environment in which people, and the architecture we create, are part of the solution. It’s also the reason why landscape-led projects are so exciting to us, as landscape is often the prism through which these challenges – and ambitions – can be most fully explored and effectively delivered.

Our work in Udaipur, India, in partnership with local not-for-profit organisation Dharohar, is a prime example, focusing on ‘10 Lakh Vriksh’ (1 million trees), Dharohar’s city-wide planting initiative to revive community parks and gardens. Studio Saar’s ambition for the project is to foster a community-led initiative that will plant and nurture a million trees across

the city, through a network of local, accessible parks and gardens. The first of these parks to be completed, Udaan Park, has recently transformed an underused, lakeside park into an accessible, safe and inclusive public space. Featuring a canopy inspired by the local birdlife, a maze, games area, and extensive planting, the park has been designed to celebrate and reconnect locals with Udaipur’s native wildlife, boost biodiversity and address challenges around net zero.

India’s urban landscape has, in the recent past, prioritised growth over the sustainable development of green cover. A result of rapid urbanisation, this trajectory has brought improvements in quality of life, including healthcare, nutrition and education, but also a situation where India’s cities are at severe risk of depleting their stock of green cover and open public spaces. Where the WHO suggests a minimum green cover standard of 9m² per capita for cities, Udaipur offers just 2m², and if we measure the allocation in terms

FEATURE

15

of accessible public parks, the figure drops down to an A3 sized piece of land per person.

The parks and gardens of 10 Lakh Vriksh aim to provide a solution. For the citizen, they will provide a free-toaccess green space that welcomes people from all walks of life. These parks will be the foundation of a drive to reinstate a connection between local urban communities and native species of flora and fauna, growing their understanding of the value of green space, and promoting a sense of stewardship towards it. For the local authority, they will provide solutions to liminal development spaces, which can be transformed with a relatively small investment. For local organisations and businesses, who are encouraged to take financial and civic responsibility of the parks in the long term, they will provide an opportunity to link local economies to sustainable urbanism.

The challenge with getting such a project off the ground was that there is no frame of reference in Udaipur. Local people had never been exposed to the idea of a ‘community park’ before, nor been educated in the impact of trees and green space on their health and wellbeing. As such, they were unable to derive a sense of their own agency in creating a resilient, sustainable

Local people had never been exposed to the idea of a ‘community park’ before, nor been educated in the impact of trees and green space on their health and wellbeing.

FEATURE

2.

16

3.

neighbourhood. Added to this is that only 4% of India can meet the threshold to pay income tax, rendering local authorities unable to meet the costs for the upkeep of local park schemes.

We knew that to seed the project, we needed to focus on smallscale interventions, and alongside

Udaan Park, we are working on three more parks as part of 10 Lakh Vriksh, including the Gulab, Swami Vivekananda and Nyay Parks. It is hoped that these will act as the catalysts for a city-wide initiative, providing physical spaces that can be utilised as a nursery to grow saplings for other sites, and as an informal

educational facility, as well as a local green space contributing social and environmental benefits.

As the first project to be completed, Udaan Park offers a blueprint to be taken forward, with the aim of setting a precedent for the inventive reuse and repurposing of materials, and making steps

FEATURE

4.

17

5.

towards its net zero ambitions by paying close attention to embodied carbon. Reclaimed tyres were used as planters, swings and play tunnels, while recycled saree fabrics were used for swing ropes; concrete waste rubble from the site was reused as fill, and all non-structural metalwork was made from repurposed steel. The canopy – an awning of 34,000 bird-shaped cut-outs – is made of recyclable and UV-stabilised plastic.

The locally sourced planting scheme was selected for its ability to withstand the harsh climate, while also helping to support and expand the habitat for the bird communities on site, with over 30 bird species recorded since opening. Meanwhile, drought-resistant grasses and small trees create tranquil, shaded spaces for visitors, alongside flowering plants and medicinal herbs. The native planting scheme has also negated the need for a water-intensive irrigation system, which along with

the (community-led) decision to leave powered lighting out of the design, have combined to significantly reduce the operational demands of the site.

Udaan Park is a landscape that has enabled us to bring environmental dimensions to sustainability – from carbon, to water, to biomass –together with social dimensions, including education, participation and local economies. As an Anglo-Indian, landscape-led studio, we see great opportunities to incorporate learnings from our projects into our work in the UK. As a country that shies away from public-private partnerships in the creation of public space, we hope that Udaan Park can provide an example of how involving local businesses and communities in the creation and maintenance of local parks increases their long-term viability and regeneration potential.

When the community is invested in the process and its value creation, through the construction, maintenance,

and enjoyment of the space, then the longevity of that space, and its role in sustainable urban development, will be far greater. Udaan Park and 10 Lakh Vriksh is just one model, which we’re excited to see flourish in the context of Udaipur, but the core idea of bringing the social and environmental sides of sustainability together holds true in a far more global context. This is what good landscape design is all about.

Ananya Singhal co-founded Studio Saar with Jonny Buckland in 2003, England. Singhal has worked on projects in the United Kingdom and India spanning industrial, commercial, landscape and private residential buildings. Singhal created the first list of heritage buildings in Udaipur for the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage.

Udaan Park offers a blueprint to be taken forward, with the aim of setting a precedent for the inventive reuse and repurposing of materials

6.

FEATURE 18

More than the sum of our parks

The Future Parks Accelerator programme, which was set up by the National Trust and the National Lottery Heritage Fund, is enabling urban local authorities to rethink the role of parks and green spaces and design new ways to look after them.

FEATURE

increase

the

the city. © National Trust Images/ Paul Harris 19

1.

1. Planting for the Plymouth and South Devon Community Forest, which will connect and

canopy cover from rural areas into

heart of

‘The need of quiet, the need of air, the need of exercise … the sight of sky and of things growing seem human needs common to all.’

In 2019, as the National Trust was planning its 125th anniversary, these words from founder Octavia Hill still resonated deeply. With 84% of the UK’s population living in urban areas, the need for quality green space in our towns and cities had never been so acute. But a dramatic reduction in local government funding and capacity was threatening the quality and existence of these spaces. As an organisation that believes access to nature is a

fundamental human need, we wanted to help find solutions.

We teamed up with the National Lottery Heritage Fund – the UK’s largest funder of public parks and urban natural heritage – to create the Future Parks Accelerator (FPA). Our goal was to enable urban local authorities to rethink the role of parks and green spaces and design new ways to look after them long-term with their communities and partners. We recruited a cohort of eight authorities that shared our passion for making nature-rich green spaces accessible for all their residents. They saw the opportunity to address challenges faced by urban areas around the UK and globally – climate change, low-quality local environments and, particularly, health and social inequalities. Their approach was to develop and share solutions that would help other towns and cities across the UK.

Covid brought a whole new sense of focus. Parks and green spaces took centre stage not only in the headlines, but also in people’s daily lives, especially for those without gardens. People (re)discovered the places on their doorsteps, (re)gained the simple

While Covid showed that we all need access to nature near us, it also highlighted the significant inequalities of provision.

Ellie Robinson

Ellie Robinson

FEATURE

3.

2. Octavia Hill (1838 – 1912) (after John Singer Sargent) oil painting by Reginald Grenville Eves © National Trust Images/John Hammond

3. Women using park gym equipment in Camden. Camden & Islington Parks for Health programme. © Islington Council

20

2.

pleasures of connecting with nature on their daily walks, and they noticed how it made them feel better.

While Covid showed that we all need access to nature near us, it also highlighted the significant inequalities of provision; many neighbourhoods lack quality, accessible green space. Just looking after existing parks and green space is not enough.

As talk turned to a green economic recovery from the pandemic, this fuelled the Future Parks ambition: what role could nature play in building back healthy, resilient, thriving and just cities and towns of the future?

But as much as everything had changed, nothing had changed. Those systemic barriers persisted; local capacity and funding was even more scarce from dealing with the pandemic. It only fuelled the determination of our partner cities and towns to remain ambitious in designing nature-rich green and blue

infrastructure into their recovery and future. It also galvanised partnerships across councils and sectors and with communities to harness their energy, capacity and leadership for change.

These are some of the stories from Future Parks. All the resources are freely available at www.futureparks.org.uk

PUTTING COMMUNITIES AT THE HEART OF PARKS

In Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole (BCP), local charity The Parks Foundation has grown to become a core partner to the new unitary authority. They bring the social and environmental mission, fundraising capability and social entrepreneurship of a charity to ensure a city’s green spaces can become a popular cause and attract money and support using sources a council cannot.

BCP Council and the Foundation developed a Green Heart Parks model, which brings together community and nature recovery in neighbourhood parks at risk of neglect. So far, this has lifted 11 community parks out of a spiral of decline, with 40 in their sights. Interventions respond specifically to the needs of local communities, such as café, toilets, family activities and events, volunteering opportunities, while also boosting biodiversity through creating wildflower meadows and planting hedgerows and trees. Communities are empowered to take a long-term role in stewardship of the space.

Camden and Islington boroughs repositioned all their parks as public health assets for the 21st century. Comprising some of the most densely populated and deprived areas in London and the UK, with high numbers of people without gardens and cars, their parks are essential ‘open-air living rooms’, and the only opportunity for many people to connect with nature. The boroughs developed a highly replicable ‘parks for health’ model, focused on: reducing barriers that prevent people from using parks; developing both universal and targeted offers for health and wellbeing in parks, including green social prescribing; and partnering with voluntary and community sector organisations to run activities and recruit participants. Their work also informs infrastructure planning and investment to ensure that spaces and facilities are designed to improve health and wellbeing.

URBAN NATURE RECOVERY

Creating space for people to connect with nature and enabling nature recovery across cities and towns is a core motivation for all FPA places. This includes easy wins, like changing maintenance regimes to create wildflower meadows from mown municipal grassland across 30–40% of a green estate. There are also more ambitious long-term plans to improve the quality and connections of a whole green infrastructure network that meets the framework and standards

FEATURE

21

3.

published in January by Natural England.

The City of Edinburgh Council became the first Scottish city to develop a Nature Network, mapping supply and demand of a range of ecosystem services provided by green space. The Linking Leith’s Parks project, delivered with the Scottish Wildlife Trust and Atkins Landscape Architects, will be the first major project driven by the Nature Network. It will design a spatial plan to connect a neighbourhood of parks in Leith, identified as one of the areas most in need of enhanced access to quality green space. The team is working hand-in-hand with the local community to develop detailed plans to make each park a nature-rich space to benefit people and wildlife. The approach will inform the development of Local Nature Recovery strategies, using this mandatory requirement as a hook to deliver greater benefit for those communities most in need, while restoring biodiversity.

Plymouth City Council is developing the UK’s first urban habitat bank to drive biodiversity net gain payments from developers into the creation of nature-rich spaces where they will most benefit people and nature across the city’s ‘Natural Grid’. This approach has been tested in the creation of a major new green lung at the heart of the city – Derriford Community Park – which aspires to be a leading centre for youth skills and training, outdoor learning and community wellbeing. Plymouth’s urban landscape is also being transformed by the new Community Forest for Plymouth and South Devon – 1,900 hectares of new forest from city centre to rural fringe will increase carbon capture across the area by 83% from current levels once fully established, supporting the city’s path to net zero.

CITIES OF NATURE

Birmingham City Council has put environmental justice and natural infrastructure growth at the centre of its vision and plan, Our Future City: Central Birmingham Framework 2040,¹ Having mapped the environmental and social inequalities facing communities across the city, Birmingham identified wards and neighbourhoods most in need of nature for people’s health, wellbeing and resilience. The actions to advance this environmental justice are now embedded in their exciting Future City Plan, with a programme of improvements to both existing green spaces and the creation of new ones, and green connectivity being planned with their communities.

1 https://www. birmingham.gov.uk/ news/article/1331/ city_s_quest_to_ become_a_leading_ international_ location_set_to_be_ supercharged_by_ new_plan

FEATURE

4. New River Walk team planting/ volunteering session led by community rangers. Camden & Islington Parks for Health programme.

© Islington Council –Vanessa Berberian

22

4.

Cities and towns

Nature-based solutions at an urban landscape scale Cities and towns in FPA and beyond are showing how the healthy, resilient and connected green infrastructure underpinning their places brings everyday joy and wellbeing for people living in them; but more than that, it can provide nature-based solutions to the existential problems of health and social inequalities, the climate crisis and biodiversity loss.

Of course, there is no silver bullet for sustainable funding, but FPA places have shown there are many good

sources of existing and new finance to capture and blend. The benefits of access to nature and green space for everyone are a powerful motivation for many funders and investors across the public, private and philanthropic sectors.

Perhaps the most important lesson of all is the power of partnerships, within and across local government, with voluntary and private sector partners and – most importantly –communities at the heart of decisions about their green spaces. This requires a change of culture from us all and

a real sense of shared vision and ambition to gain the big prize of naturerich cities and towns.

Ellie Robinson has led the National Trust’s strategic programme and partnerships on urban green space since 2016. Together with Drew Bennellick at the National Lottery Heritage Fund, she set up the Future Parks Accelerator. Previously she was Assistant Director of External Affairs at the Trust, influencing decisions on environment and land use policy, funding and practice.

FEATURE

5. Devon Community Forest, which will connect and increase canopy cover from rural areas into the heart of the city © National Trust Images/ Paul Harris 5.

23

in FPA and

beyond

are showing how the healthy, resilient and connected green infrastructure underpinning their places brings everyday joy.

Lessons for a changing climate

There is much to learn from arid regions to ensure that natural resources are adequately conserved. Three case studies from Dubai illustrate approaches to irrigation, planting and parks in the Middle East.

As the climate emergency intensifies, conserving natural resources has become an urgent priority. In terms of public parks, managing our water resources wisely through responsible and efficient irrigation, coupled with improved planting media and

selection of place-appropriate and locally available plants, plays a critical role in resilience for longterm sustainable maintenance and reduction of water consumption. By utilising responsible water conservation and horticultural strategies, we can effectively

1. Al Ittihad Park under The Palm Monorail showcases native plant species over ten hectares.

Photography by Alessandro Merati © Cracknell

1.

FEATURE 24

Colleen D’Souza and Mohan Baporikar

There is much to learn from these arid regions to ensure that natural resources are adequately conserved.

maintain the vibrant green spaces parks provide while reducing their impact on water demand and increasing their contribution to local sense of place.

In the UK, where it sometimes seems like it never stops raining and supply of water is something we can take for granted, there is less available fresh water than many realise. In 2021, Environment Agency Chair Emma Howard Boyd said: ‘If we continue to operate as usual, by 2050 the amount of water available in England could be reduced by 10 to 15 percent, some rivers could have between 50 and 80 percent less water during the summer and we will not be able to meet the demands of people, industry and agriculture.’¹

There are nearly 200,000 hectares of parks and green spaces in the UK.² With changes in rainfall and evaporation we need to think carefully about our use of water in parks and choice of planting with regard to water demand. These might seem

considerations that until recently only belonged in regions like the Middle East, where rain in Dubai can be only 13cm a year and temperatures can reach 48 degrees Celsius, but this is changing and there is much to learn from these arid regions to ensure that natural resources are adequately conserved.

Our work in the Middle East has taught us at Cracknell much about sustainable irrigation and planting strategies, and we have developed a thorough understanding of resilient, efficient and adaptable techniques.

IRRIGATION

Responsible irrigation practices conserve water and energy, reduce soil erosion and pollution, and improve plant health. Smart irrigation systems use technology to monitor soil moisture, wind speed and other factors, enabling operators to optimise irrigation programmes to further reduce water consumption.

With depleting available fresh water, exploring alternatives such as rainwater harvesting, recycled water (treated effluent/grey water) and condensate water has become ever more important. Here are some methods we have used.

The power of drip irrigation systems: Unlike traditional sprinkler systems that disperse water over a wide area, these systems target specific plant root zones in a park, reducing water waste from run-off and evaporation.

Harnessing weather-based irrigation controllers and soil moisture sensors – the tech for precise watering: These devices adjust watering schedules based on local weather conditions and soil moisture content, preventing overwatering on rainy days, or underwatering on hot ones. This smart approach ensures that parks are only watered when needed.

1 https://www.gov. uk/government/ news/new-watersaving-measures-tosafeguard-supplies#: ~:text=If%20we%20 continue %20to%20 operate,of%20 people%2C%20 industry%20 and%20 agriculture

2 https://www. fieldsintrust.org/ green-space-index

FEATURE

3.

2.

2. Provision for natural play encourages learning and interaction with nature. Al Ittihad Park 02.

Alessandro Merati © Cracknell

3. This resilient park landscape is actually the skin of the museum buildings. Museum of the Future.

© Museum of the Future

4. A canopy of native palms provides shade for exercise. Al Ittihad Park.

Alessandro Merati © Cracknell

4.

25

Organic mulching – a simple yet effective tool: Mulch retains water in the soil by reducing evaporation and ensuring that plants have a consistent water supply, thereby limiting the frequency and amount of water needed. Mulching also suppresses weeds and regulates soil temperature. Recycled material weed-control barriers can also help in reducing evaporation, cutting out light and nutrients to unwanted weeds that compete with the desired plants.

Soil moisture retention additives can also be used to reduce the percolation rate within the soil. These additives can be sourced from natural materials/minerals such as volcanic tuffs, perlite and Cocopeat. Mulching and retention additives also improve the soil structure of sandy soils and reduce fertiliser use through leaching prevention.

Rainwater harvesting: nature’s answer to irrigation needs:

Rainwater collection systems can be used to gather and store rain from rooftops and other surfaces in irrigation storage tanks, thus reducing reliance on municipal water supply. Where possible, water can be harvested by installing a sub-surface drainage system from which the water can be treated and fed back into the irrigation network.

Using grey water – a second life for used water: If local regulations permit, consider using grey water (lightly used water from sinks, showers, etc.) for irrigation. This practice not only conserves water, but also reduces the strain on sewage treatment systems. Grey water is not commonly used in the UK at all and there’s a perception that it may be less safe than mains or borehole water,³ but we are starting to investigate its use more as the climate crisis worsens, and this should be encouraged.⁴

In the Middle East, use of grey water for irrigation of public parks, streetscapes and major developments is normal. In Dubai, the quality of treated grey water is very good and there is a separate network of Treated Sewage Effluent (TSE) lines supplying treated water for irrigation. Many parks have their own storage tanks supplied from this Municipal TSE network. The water recovered from sewage is ploughed back into greening the cities rather than discharged into the sea. Treated water also benefits plant health, as it carries minimal amounts of nutrients such as nitrogen. Where practical, reed bed filtration systems can be used to treat grey water without using energy, while also creating wetland areas attracting birds for nesting sites.

Implement a water budget: A water budget can help parks stay on track with their water conservation goals by setting a limit on the amount of water to be used for irrigation. This strategy requires careful planning and monitoring of water use. In the MENA (Middle East & North Africa) region the Municipality’s sustainability guidelines, such as ESTIDAMA in Abu Dhabi, set water budgets that must not be exceeded; for instance, public open spaces with less than 70% hardscape cover, i.e. most parks, must not use more than 4.5 litre/m² water in a day.

Practice seasonal adjustments: Adjust watering practices based on seasonal changes, watering less in cooler months when plants are often in a dormant phase and more in warmer, drier months when water demand increases. Daily timing adjustments are also important. Irrigating during early morning or late at night in the summer minimises evaporation losses and allows efficient percolation. It is good to irrigate in short but frequent ‘bursts’ to minimise wastage and evaporation.

Windbreaks and shade structures – lowering evaporation rates: Windbreaks and shade structures can help reduce the rate of evaporation, allowing plants to retain more moisture. They can also provide aesthetic and functional benefits to parks, offering shaded areas for visitors.

5. Masses of nectar-rich flowers support native bees – including black Carpenter Bees (Xylocopa (Ctenoxylocopa) fenestrata). Museum of the Future.

In the Middle East, use of grey water for irrigation of public parks, streetscapes and major developments is normal.

3 https://www. foodstandards. gov.scot/ self-assessmentresources/watersources

4 https://www. waterwise.org. uk/wp-content/ uploads/2018/02/ Brewer-etal.-2001_Rainwaterand-Greywater-inBuildings_Projectand-Case-Studies.pdf

© Cracknell

6. Informative signage throughout the park teaches visitors about the value of native plants. Al Ittihad Park. © Cracknell

5.

6.

26

7. Back of house: The hub of the smart irrigation system manages the water application based on moisture content data received from soil moisture sensors and weather information from a local weather station. Museum of the Future.

8. The shade from the varied native and adaptive canopies in Zabeel Park are a huge draw for Dubai residents and visitors alike. Zabeel Park.

Capillary breaks to avoid saline ground water: Summer temperatures compound problems with saline ground water in the Middle East. High temperatures draw water to the surface leaving salt on the soil surface. If left to build up it disturbs the soil pH and prevents plant roots from taking up nutrients. To mitigate this, a capillary break is introduced under tree/palm pits to prevent saline water ingress.

Eliminate need for transportation of water: The use of many of the techniques here, such as rainwater harvesting, mulching, shade and selection of native water-wise planting, should eliminate the need for any transportation of water.

HORTICULTURE

The skills involved in water-wise plant palette selection and native plant cultivation are a vital component of tackling climate change and the sustainability challenges of water shortages. Responsible horticultural practices to be used in public open spaces include:

Specifying and sourcing native plants has the added benefit of improving ecological value by supporting native insect, bird and animal populations.

Routine maintenance – preventing water waste and Legionella growth: Even the most advanced irrigation system can waste water if it’s not well maintained. Regular inspections are vital to identify leaks, clogs, or other malfunctions, enabling timely repairs. A well-maintained irrigation system ensures efficient water use for a longer period. There should be a strategy for Legionella prevention by avoiding stagnant water at any point in the system. It’s advisable for the maintenance contractor to include in the O&M Manual a Legionella Management Plan based on the design drawings.⁵

Xeriscaping: Choose native, preferably local, adaptive droughttolerant plants that need less water and fewer nutrients to thrive. By opting for these species, parks can maintain biodiversity while reducing both their water footprint and requirements for fertilisers. Xerotropic plants possess unique adaptations, such as deep root systems and water-storing tissues, enabling them to survive in arid conditions, to withstand prolonged periods of drought and so reduce water consumption significantly. It’s also important to mitigate the effects of high mortality rates during the summer months in hot climates by choosing salt-tolerant species. Specifying and sourcing native plants has the added benefit of improving ecological value by supporting native insect, bird and animal populations.

Hydrozoning – a strategic approach to plant placement: Group plants with similar water needs together to minimise over- or under-watering. This practice ensures that each section of

the park receives the right amount of water, promoting plant health.

Nutrients – providing for growth in a poor planting medium: Desert sand is inherently devoid of plantaccessible nutrients; hence the planting medium must be amended to provide the plants with nutrition for growth. Planting medium is a homogeneous mixture of desert/ agricultural planting soil, organic fertiliser/compost and inorganic slow release/compound fertilisers, including

© Cracknell

Alessandro Merati © Cracknell

9. The flowers of native Tecomella undulata add vibrant colour to Zabeel Park.

© Cracknell

7.

8.

l8.htm 27

9.

5 https://www.hse. gov.uk/pubns/books/

a soil moisture retention additive to improve the water-holding capacity, allowing water to be retained in the root zone for release at the plant’s wilting point.

Compost helps mobilise the existing soil nutrients so that good growth is achieved with lower nutrient densities. By supplying humus and nutrients, biodiversity and long-term soil productivity is improved. The addition of compost also improves soil texture and the ability to retain moisture. An inorganic slow-release fertiliser is recommended to provide a steady supply of nutrients over a longer period of time, without waste through leaching.

Minimising transportation of materials: Minimising importation of planting materials and avoiding long transportation saves time and costs. Compost sourced in the UAE is generally local cow manure, heat treated and sterilised. Alternatively, it is sourced locally through green waste and meat meal from local abattoirs.

When developing green space in coastal environments, the existing soil is full of accumulated salt. The planting medium to be used is then sourced from the interior of Dubai where the inland ‘sweet soil’ (agricultural soil) is fit for planting. Other than manufactured fertiliser tablets, all plant nutrition is sourced regionally. Implementing water-efficient irrigation practices in public parks is a relatively small but important aspect of tackling the climate emergency. Landscape architects have a vital role globally in influencing developers and local authorities alike in the merits of water-wise schemes and placesensitive native planting. The role of public awareness and education should not be underestimated: signage, interpretation and events programmes can teach visitors about water conservation, why it’s essential and what they can do to help by adopting water-saving practices in their homes and communities. By employing these strategies, parks can continue to provide beautiful, green

spaces for communities to enjoy, contributing to health and wellbeing, while making a tangible contribution to global water conservation efforts.

CASE STUDIES

Zabeel Park

Zabeel Park in Dubai provides a nearly 50-hectare oasis of relaxing shaded green space, popular with the whole community. An integrated smart irrigation network optimised water usage by using weather-based sensors to analyse local climate patterns and adjust irrigation schedules accordingly. By avoiding overwatering and minimising evaporation, the park achieved a 60% reduction in water consumption compared to a non-smart system. The smart network also enabled remote monitoring and control, allowing park authorities to fine-tune irrigation settings in real time and provide necessary nutrients via a chemical injection system. The 2005 project not only conserved water

10. Native trees used include ghaf (Prosopis cineraria), Ziziphus spina-christi (sidr) and acacias, perfectly adapted to local environmental conditions and requiring minimal water and fertiliser to sustain them. Museum of the Future.

FEATURE

Implementing water-efficient irrigation practices in public parks is a relatively small but important aspect of tackling the climate emergency.

10. 28

© Cracknell

11. The steeply sloping nature of the mound elicited concerns about rapid loss of irrigation water from run-off from the root zone. To counteract this, water is delivered in short frequent ‘bursts’ to minimise wastage and evaporation, and subsurface geocells allow excess irrigation and stormwater to be harvested and recycled. Museum of the Future 04.

resources, but also demonstrated the feasibility of employing technologydriven solutions for sustainable landscaping practices in comparable parks. The plant selection strategy focused on incorporating a combination of visually appealing native and xerotropic species well suited to Dubai’s climate, providing an ecologically balanced, biodiverse and resilient landscape.

Museum of the Future

harvested and recycled. This ensures it isn’t released into the urban drainage system. Water usage under this system was reduced by 25-30%, substantially improving on the original KPIs (key performance indicators).

A key to ensuring landscape sustainability was to select plants with a low water requirement.

Al Ittihad Park

Al Ittihad Park in Dubai exemplifies a sustainable approach to landscaping by utilising more than 60 indigenous tree and plant species across 10 hectares, including Prosopis cineraria, Ziziphus spina-christi, Adenium obesum, Jasminum sambac, Typha domingensis and Moringa peregrina These native species showcase the distinctive beauty and resilience of the local flora, while minimising water requirements and maintenance demands, promoting biodiversity.

On inception in 2012, a continually updated list of native plants from which to expand, maintain and replace dead specimens was drawn up and continues to be used today. Postcontract management on site was vital to ensure adherence to the species lists and to see that contractors didn’t default to easier-to-source tropical species. Continued pressure on local nursery suppliers has helped to maintain a healthy stock and supply of native species regionally, and to build a consensus among nursery growers that native plants are a viable and more sustainable option.

This 2022 2-hectare resilient park landscape is actually the skin of the museum buildings – a berm and roof garden with a topographical profile not normally seen in urban Dubai. Working with slopes steeper than 60 degrees required innovative design solutions to suspend a soil ‘carpet’, as standard landscape techniques for soil retention could not be used. Green wall technology together with a recycledmaterial geocell system retain and stabilise the slopes, in conjunction with specialised in-line drip irrigation systems using grey/treated sewage water. All of these elements are contained within an engineered ‘sandwich’ that clothes the mound in its xerotropic living green carpet. Cocopeat (bio-product) and lightweight perlite improve the water-holding capacity of the planting medium and create a light soil that helps to limit the structural loads.

A key to ensuring landscape sustainability was to select plants with a low water requirement, and to design smart irrigation systems that would automatically manage the water application based on moisture content data received from soil moisture sensors and weather information from a local weather station. The steeply sloping nature of the mound elicited concerns about rapid loss of irrigation water from run-off from the root zone.

To counteract this, water is delivered in short frequent ‘bursts’ to minimise wastage and evaporation, and subsurface geocells allow excess irrigation and stormwater to be

One of the primary plants used for the mound was a variety of fleshy sea-purslane – Sesuvium portulacastrum – commonly found by the Middle Eastern coast. Quick growing, tolerant of heat/salt and requiring minimal irrigation, they are the ideal plant to ‘green’ the ‘mound’ in a sustainable way. Native trees used include ghaf (Prosopis cineraria), Ziziphus spina-christi (sidr) and acacias, perfectly adapted to local environmental conditions and requiring minimal water and fertiliser to sustain them. Their masses of nectar-rich flowers support native bees, and seasonal fruits attract wild bird populations. Further ecological value is brought by the native grasses and ground covers such as Cenchrus ciliaris, Zygophyllum qatarense and Sporobolus spicatus, which are supremely adapted to poor saline soils and are self-propagating; their seeds sustain local birds such as hoopoes, sparrows, sunbirds and white-eared bulbuls.

Colleen D’Souza is Director and Head of Cracknell’s Integrated Horticulture Team. She has been instrumental in expanding the plant typologies used in the MENA regions over the last 30 years, challenging local standards and adding ecological and resilience value.

Mohan Baporikar is a Director of Cracknell’s Integrated Irrigation Team. He is an ardent enthusiast for the implementation of efficient and sustainable design practice within irrigation and MEP works, learned from over 30 years of designing, executing and maintaining many types of irrigation, drainage and water feature projects largely in the MENA region.

FEATURE

© Cracknell

3.

29

11.

A new park and a greener future for Tottenham Hale

A park in North London is to be completely renewed, addressing climate resilience and the needs of a fast-growing population.

Down Lane Park is a well-loved green space at the heart of a rapidly changing community in

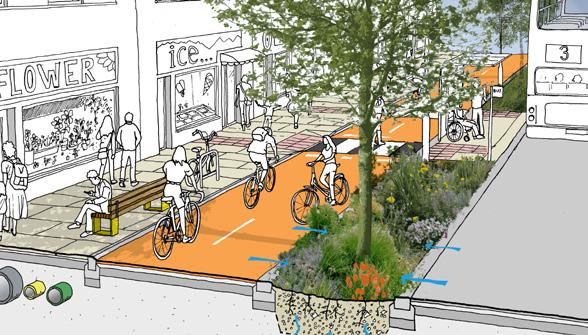

Tottenham Hale. It is a park of two distinct halves, which have differing but established landscape characters. Our masterplan for the park’s renewal has evolved through a process of co-design we have led since spring 2022, alongside our client Haringey Council (combining both Parks and Regeneration departments).

Plans to improve Down Lane Park have been created in partnership with

the Community Design Group (CDG), which preceded our appointment and was already a fully functioning group when we joined the project. The CDG is a diverse group that represents the local community and provides a range of lived experience. Their agreed focus is to shape the masterplan proposals, inform engagement strategy and build support for designs by channelling feedback from residents and groups using the park.

FEATURE

1. Community consultation event.

© Levitt Bernstein

1. 30

Kate Digney

Our initial aim of the co-design process was to establish two masterplan options to be taken to wider public engagement in the autumn.

Our first session with the CDG took place in May 2022 and aimed to give comfort in relation to our track record in delivery and our practice’s approach to people-centred and sustainable design. Working with Lisa Taylor from Coherent Cities as co-design facilitator, we mapped out the structure of meetings (always starting with a recap from the previous) and marked a timeline for the co-design process, with the goal of a planning submission in the following spring. The CDG’s commitment and investment in the process has been extensive and hugely appreciated.

Early CDG sessions involved understanding the site through the eyes of local people, agreeing priorities to be addressed and how ‘success’ might be measured for co-design. Key issues quickly came to the fore, such as inclusive access, opening up the park for more groups to feel safe and better catered-for (including young women and girls) and tackling crime and antisocial behaviour. Alongside these themes came an outpouring of concerned comments about funding, access to nature, adequate toilet provision and – the big one – how to create a park with sufficient resilience to support new residents resulting from the growth of Tottenham Hale.

Each CDG meeting dealt with a handful of pre-agreed topics like boundaries, entrances, and pathways and included a masterplanning session where the group was subdivided into tables, working with a landscape architect to express preferences on aspects such as routes, entrances, play locations and, critically, a community ‘hub’ building (either augmenting the existing or replacing).

Boundary railings were a significant talking point within the group and designs incorporated a range of responses, depending on setting and the intensity of use within their bounds. To the north, Down Lane Park presents as a classic London park, with perimeter railings lined by mature trees. The western street edge will be partly planted with native hedging, with future hedge-laying work envisaged through community stewardship. Dead hedges, formed by deadwood sifted from an abundance of lime (Tilia) trees and branches from large-scale lifting of clear stems, offer further habitat value while improving sightlines and a sense of safety within the park. At maturity, these new interventions will allow the future removal and recycling of railings, with funds from the scrap metal value being ploughed back into the park. To

the eastern street edge, there is an aspiration to connect a future school street to the park with the adjacent Harris Academy school; railings will be removed to help the park reach out and entice children across bridges over SuDS basins and towards glimpses of new play features. The park will remain ‘well defined’ but we expect these moves to enhance greening, improve permeability, and accessibility and start to reinvent the park’s current identity – given also that gates and railings are never locked at night under Haringey policy.

Our initial aim of the co-design process was to establish two masterplan options to be taken to wider public engagement in the autumn. This was achieved following six successful meetings with the CDG, and the strength of consensus within the group meant that the main key variable between the options was the location of the hub building. Public responses didn’t offer a clear consensus for either option for the hub location, and an exercise to review the existing building concluded that the form and structure was too constraining to be viable. The location of the existing facility repurposes a former recreational building (with bowling green) tucked into the south

FEATURE

2.

2. Fuzzy felt activity during the community consultation.

© Levitt Bernstein

31

of the park. Safe access through the park out of daylight hours and a lack of a park-facing sense of arrival are both problematic qualities. Despite very concerted efforts to address these failings by the facility’s operator, the decision to provide a high-quality new building, designed using Passivhaus principles, was agreed … the next challenge was to agree its location! A study showing a series of alternative building locations was put forward to the CDG, with an evaluation against each to consider aspects such as visibility, impact on trees, ease of access out of daylight hours and street presence. This stretched the agreed testing from two to eight locations but was critical to maintain support of the CDG and ensure that all voices and opinions were adequately considered. The co-design process can mean that unforeseen issues arise and radically change, or impact upon intended workflows, but flexibility in approach (and programme!) is critical to both sustaining relationships and achieving an outcome that maintains the confidence of the group.

The hub ‘vision’ is for a landmark, sustainable building that fulfils the needs of the local community, while minimising its impact on the park. A community garden will sit directly alongside the hub (another area of hardstanding to be turned into green space) with a playful boundary celebrating garden activities and inviting people to learn more about it. The hub building will provide ‘eyes’ onto the park, with a café offering a south-facing terrace extending towards a multi-age play area with existing trees. Existing sports provisions include tennis and an all-weather pitch – both to be retained and complemented by new courts for basketball and netball. A relationship between the sports courts, play and hub building will provide interstitial spaces to be designed and exploited by young people.

A recent engagement session to workshop ideas with young people, including women and girls, has shaped proposals for spaces that can support performance, socialising, watching sports, reading and flexible seating forms for friends and sibling groups.

Diversifying the offer of current ‘dead space’ within the park was a key observation from the outset and ensuring flexible use of space will be fundamental to detailed designs. Colour, pattern and vibrancy of surface materials have been favoured within areas around the hub and leisure zone, and the style of work by locally celebrated artists such as Yinka Ilori have been discussed as a forward-facing expression of the park’s identity. Traces of a rich cultural and manufacturing history around the

park also have their place, and play concepts being developed include pencil-shaving forms as sculpture, play and flexible seating.

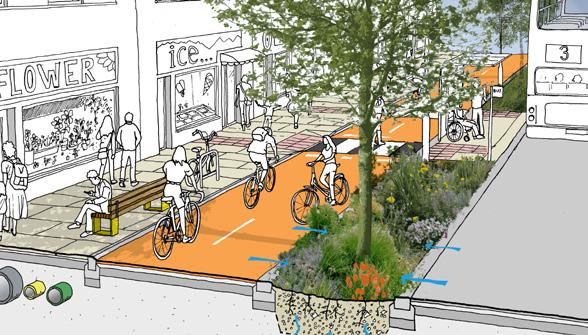

The new Down Lane Park masterplan will create a high-quality ‘green destination’ for local people, but the success of the project will also be measured on how the park serves as a green waymarker for active travel to wider Haringey destinations, including The Paddock, Tottenham Marshes, Walthamstow Wetlands and Tottenham High Road. Increasing

A recent engagement session to workshop ideas with young people, including women and girls, has shaped proposals for spaces that can support performance, socialising, watching sports, reading and flexible seating forms for friends and sibling groups.

FEATURE

3. South entrance facing play area.

© Levitt Bernstein

4. North path facing SuDS scheme.

© Levitt Bernstein

4.

32

3.

the permeability of the park, and the ease of arrival for all, is complemented by the ability of the park to signpost these wider destinations and act as a stopping point for cyclists and other wheeled vehicles. New park entrances to the south will promote alternative corridors of movement to and through the park, including in evening times when vibrancy will be created by neighbouring retail offers, the new community hub building, sports courts and more convenient park entrances. Lighting design (by Light Follows Behaviour) will complement and strengthen these safe movement routes, reinforcing points of arrival and celebrating new community assets like the hub building.

Phase one of the masterplan has just been awarded the maximum level of funding available from the Mayor of London’s Green and Resilient Spaces Fund (GRSF) for 2023. This will kick-start the creation of new diverse habitats and the introduction of sustainable drainage devices within the park, layering through interventions for play and spaces for outdoor gym and self-guided sports.

Our engagement with Haringey Council’s parks team, who are responsible for gardening and maintenance within the park, has informed proposals, and selective mowing regimes are already being introduced to better understand the species within the existing seed bank. Habitat creation will diversify species being supported while also creating more pleasant and attractive spaces that give a stronger sense of connection with nature. Existing woodland will be augmented to ensure ‘cool spaces’ are achieved in summer months and access to these areas will be substantially enhanced by a new network of crossing and perimeter paths (all with permeable construction).

Phase one will adopt the principles of climate change resilience, with a diverse new tree and plant palette selected for suitability for the changing UK climate. The introduction of new basin landforms edging the park to the east will allow surface-water runoff to be captured from an adjacent highway, reducing pressure on

drainage systems while creating a new habitat type for the park. The basins will be playable, promoting further interaction with the park landscape via a new network of pathways designed to connect all visitors with woodland areas – something the park currently lacks. Access to woodland ‘cool spaces’ will allow refuge for both people and wildlife, with features including dead hedges and log piles. These works will commence in time for spring tree planting in 2024, when we hope to welcome every member of the Community Design Group to help as the first new trees are planted.

Kate Digney is Head of Landscape at Levitt Bernstein where she leads sustainable design across a range of project sectors. Throughout her career Kate has drawn insight from working with local communities, putting the needs of local people at the heart of place-making proposals.

FEATURE

5. Landscape masterplan. © Levitt Bernstein

33

5.

Reclaiming the Gardens

The subject of many campaigns, this park in the heart of Aberdeen is now welcoming a new generation of users.

Despite this heritage, Union Terrace Gardens has been the subject of fiercely waged disputes that have split the city. Such was its decline over the past 20 years, there was even a proposal to fill in the park valley with a shopping mall.

Aberdeen’s Union Terrace Gardens is one of the UK’s most important park regenerations. Sited in the heart of the city, the park was designed by the architects who built many of the listed granite buildings that surround it and for which the city is famous.

While Union Terrace Gardens is the city’s most significant park, at £28m the level of investment in this project still contrasts sharply with diminished funding to other major parks and green spaces throughout the UK. The choice demonstrates trust in the power of high-quality green space to lead the regeneration of a city centre. We are at the start of seeing how that turns out.

The two-and-a-half acre Gardens are in a steep river valley and so have striking topography for a city centre. They opened in 1878 when the ‘bleaching greens’ next to the railway line were given to the people as a pleasure ground by the council and designed with lawns, a grand granite staircase to the lower level, fine statuary and formal planting including a Bon Accord crest, the Aberdeen coat of arms. The site is bounded to the north by a viaduct and to the south by Union Street, the city’s main commercial thoroughfare. To the east is the railway line and to the west Union Terrace. The decline

All images are of Union Terrace Gardens.

7.

© Christoper Swan

FEATURE 1.

Kirstin Taylor

1. 34

LDA Design had to somehow pivot distrust, disillusionment and consultation fatigue into a groundswell of support for regeneration.

of the Gardens in the late 20th century reflected the wider deterioration in the condition of central Aberdeen. Scotland’s third city grew out of fishing and shipbuilding and then the petrochemical industry. Industry downturn and the opening of two shopping centres led to Union Street going from the bustling Granite Mile to empty units and unkempt buildings.

By the start of the 2000s, the charm and beauty of the Gardens had eroded, and personal safety had become a growing concern. Poorly lit and with no facilities, a thick canopy of mature trees obscured sightlines and there was nothing to attract visitors and keep the place busy. The park became a magnet for antisocial behaviour, drug-taking and drinking, with even a small, tented settlement.

Proposals to regenerate the Gardens failed to unite support behind them, and then in 2010 a particularly intense public concern was triggered when an oil tycoon proposed building a subterranean shopping mall in the valley, with ribbons of modern park above. The scheme appeared to promise a massive injection of external investment in the city centre, and for some this seemed good enough. However, the Friends of the Gardens fought a hard campaign. The argument

that the city needed green space more than increased major retail space was won, but not before bitter divisions had opened up between residents across the city.