landscapeinstitute.org Summer 2023 £15.00 Making it home: Creating a hospitable landscape

Product Range: Heavy-Heavy, beamsize: 14 x 21 cm

Wood option: FSC® Recycled 100% Hardwood

Twin option: Lava Grey (recyclate)

STREETLIFE BV enquiriesUK@streetlife.com I www.streetlife.com I t. +44 (0) 20 30 20 1509 I FSC® license number: C105477 Drifter Bench with USB Charger Lava Grey (recyclate) TWIN Extraordinary for Landscape Architects Rough&Ready Curved Bench

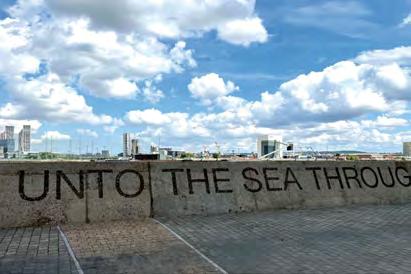

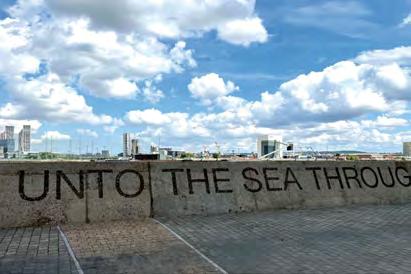

Thames Barrier Park Royal Docks in London (UK) by Mott MacDonald

Heavy-Heavy Loungers

Project:

Product:

Mobile Green Isle Oval movable & modular seating elements Love Tub CorTen

PUBLISHER

Darkhorse Design Ltd

T (0)20 7323 1931

darkhorsedesign.co.uk

tim@darkhorsedesign.co.uk

EDITORIAL ADVISORY PANEL

Saira Ali, Team Leader, Landscape, Design and Conservation, City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council

Stella Bland, Head of Communications, LDA Design

Marc Tomes CMLI, Director, Allen Scott

Landscape Architecture

Sandeep Menon, Landscape Architect and University tutor, Manchester Metropolitan University

Peter Sheard CMLI, Landscape Architect

Jaideep Warya CMLI, Landscape Architect, Allies and Morrison

Jenifer White CMLI, National Landscape Adviser, Historic England

LANDSCAPE INSTITUTE

Editor: Paul Lincoln

paul.lincoln@landscapeinstitute.org

Copy Editor: Jill White

Proof Reader: Johanna Robinson

Immediate Past President: Jane Findlay PPLI

CMLI

CEO: Sue Morgan

Head of Marketing, Communications and Events: Neelam Sheemar

Landscapeinstitute.org

@talklandscape landscapeinstitute landscapeinstituteUK

Creating the hospitable landscape

Landscape architects are ideally placed to create a welcoming environment for everyone, from tourist, refugee and visitor to pedestrian or cyclist. The welcome may be developed through signage systems, cartography, planting, or a hard landscape with materials that carefully offer a route and a navigation through the city. The creation of maps and signpost schemes, like Legible London and Legible Bristol, are interesting examples that offer a form of welfare, an embrace of the visitor that says, you are welcome in this place.

and a student-led consultation in Hackney, East London.

The research section highlights thermal comfort as an essential area of landscape expertise and demonstrates how co-design has become an essential area of expertise across all of the built environment professions. And finally, LI chief executive Sue Morgan examines the ground we stand on to ask how much of it provides a truly hospitable landscape.

Paul Lincoln Editor

Print or online?

Landscape is available to members both online and in print. If you want to receive a print version, please register your interest online at: my.landscapeinstitute.org

Landscape is printed on paper sourced from EMAS (Environmental Management and Audit Scheme) certified manufacturers to ensure responsible printing.

The views expressed in this journal are those of the contributors and advertisers and not necessarily those of the Landscape Institute, Darkhorse or the Editorial Advisory Panel. While every effort has been made to check the accuracy and validity of the information given in this publication, neither the Institute nor the Publisher accept any responsibility for the subsequent use of this information, for any errors or omissions that it may contain, or for any misunderstandings arising from it.

Landscape is the official journal of the Landscape Institute, ISSN: 1742–2914

© 2022 Landscape Institute. Landscape is published four times a year by Darkhorse Design.

This edition of Landscape considers what it means to create a hospitable environment. Considering a childhood experience of learning to cycle in North London and a UNESCOsupported child-friendly landscape in Ilford, we also showcase the way in which the early work on Legible Bristol and Legible London schemes has further evolved from New York to Toronto, Brick Lane and Bankside. We explore plans for dramatic improvements in Newhaven and celebrate the unsettling life of the City of London bollard.

Our interview with the creators of Elephant Springs traces the development of a landscape made from porphyry stone as it is carved and tested and then transported from its quarry to create a childfriendly environment in Elephant Park. Our book extract explores how skateboarding has improved the hospitality of Malmö, and our university briefings update on an innovative collaboration in Bangladesh

WELCOME

landscapeinstitute.org Making it home: Creating a hospitable landscape Cover is based on a photograph of the Legible London map. Credit TfL.

3

Contents 4 Signage makes a world of difference to an urban stroll 6 Signs of life A new park seeks to become iconic draw 34 Elephant Springs Eternal Examining making and design 39 The Experience Book Creating an inclusive environment through wayfinding 29 Newhaven’s Wayfinding Masterplan When it comes to history, bollards have a clear role to play The hospitable bollard 24 FEATURES A rich heritage inspires a child-friendly public realm Ilford through the lens 19

Sue Morgan selects some of her most hospitable landscapes 61 The Ground We Stand On 64 CAMPUS: Learn from anywhere LI LIFE RESEARCH 46 Skills Development Report Launch of an online hub UNIVERSITY BRIEFING 42 Gramer Haor Helping a village to grow sustainably RESEARCH RESEARCH 52 The Value of Co-design The ‘Towards Spatial Justice’ Research Project 57 Thermal comfort Ensuring liveability by developing heat resilience UNIVERSITY BRIEFING Showcasing work on the Nightingale Estate 48 University of East London 5

Signs of life

Signs can make the world of difference to an urban stroll. Designed to point, indicate and control – sometimes they also offer comfort and support.

FEATURE

No 1. ©

1. Model Traffic Area

British Pathé Ltd

6

1.

1 Model Traffic Area, London https://lordshiprec. org.uk/what-to-seedo/model-traffic-area/ https://museummum. com/2018/05/17/ local-london-mta/

Jill White

We are always looking for signs. From judging the clouds to see if the weather is on the change, eyeing the colour of the smoke emanating from the Vatican at conclave, to looking for that road-signed turn-off we’re supposed to be taking, or checking if that’s a disabled toilet over there. We’re looking for messages and reassurance, an acknowledgement that this place has us in mind, that it’s designed to be used by people like you and me, or that it’s safe. Although we bridle at over-zealous instruction signs and hate feeling corralled, having the ‘rules’ set out in our environments is often what makes it work. Funnily enough, those double-yellow lines are there for a reason.

We’ve been keen on signs for a long time, from cave art to traditional travelling cultures which recorded important hunting and subsistence locations through graphics, song and story. Romans invented milestones and from the 16th century parishes had responsibility for signposts in their areas. When cars came along from the 1890s onwards, the first warning and danger signs appeared for steep hills and bends, as vehicles then had much more entertaining braking and clutch capabilities. Before the advent of mass-production of relatively cheap vehicles, road signage was largely a local matter, and the result was a variety of styles and forms sometimes understood clearly only by locals. In the late 1950s, the government commissioned designers Jock Kinneir and Margaret Calvert to sort out the mess and to come up with a coherent style which was later applied across the UK and became the international template that we know today. It even has its own fonts designed by Calvert – ‘Transport’ and ‘Motorway’ – chosen

after rival fonts were exhaustively tested by aircraft pilots sitting on a platform in the middle of an airfield, working out what could be seen at what distance and travelling speed. It was Calvert who previously came up with the black type on yellow background approach (for Gatwick Airport), which is still widely recognised as the best, especially by the visually impaired. The mix of lower-case and capital letters enables them to be read faster than just using all capitals. The three shapes employed are codified as triangles for warnings, circles for giving orders and squares for supplying information. All of our suite of signs for pedestrians, horse riders, cyclists and vehicles now complies with the Kinneir-Calvert system.

Of course, not all signs are visual and on a flat surface. We take clues about how we are likely to experience the environment in the form of sound, touch and smell, too. The reassuring bleep of the controlled crossing that helps us navigate a busy road; the warning reversing alarm of the local authority dustcart; the passenger announcements on public transport – they’re all given as a form of sign to

help us get around and function in the world safely. Other more subliminal signs are displayed by features of landscape schemes: planting that allows enough visibility for vulnerable groups to feel safer; benches which have proper back and armrest support for disabled or elderly users, inviting a rest; also the use of scented plants for the visually impaired. These, too, are signs which make for a friendly landscape, one that says, ‘Yes, we’ve thought about you and we hope we’ve designed it so you’ll like it enough to visit again.’ Of course, there’s a place for warning signs such as ‘Danger’ and ‘Offenders will be towed’ (also designed for our wellbeing), but it isn’t always about the rules. How do we learn about all of this signage, overt and otherwise? As a child, I learned how traffic lights worked, what road signs meant and how to behave as a cyclist at the Lordship Recreation Ground in Haringey, North London. Apparently, the world’s first, opening in 1938,¹ to this day it still has some of the same layout. Learning the rules can be made fun and the Model Traffic Area also allowed me to feel that here was

FEATURE 7

something designed for me and so I was welcome there.

Later in life as a landscape architect designing a play area in a local park, I came upon this feeling again when children told me that the first thing they do when they go into a new area or park is to look for the brightly coloured stuff and then they know it’s for them – a sign that it’s the space where they’ve been thought about and so feel welcome. I was thinking how fed up they must be with the same old coloured equipment, but they were interpreting it as a navigation sign. Of course, they also enjoyed the more natural non-coloured play facilities, too.

What are we doing today to help people navigate or to signal a welcome? And how has this changed in recent years? Legible London was set up particularly to help pedestrians find their way around the capital more easily. The project was originally the brainchild of Pat Brown of Central London Partnership around 1999. It was promoted by a number of London boroughs together with Transport for

London and has now been taken up across the capital. It was given a boost by the London Olympics. TfL worked with boroughs, businesses and disability groups to create an easy-touse wayfinding system of routes and signage that was also linked to transport hubs and underground station exits. Although this was achieved using a suite of recommended sign styles, information ‘pillars’ and other physical devices, it also tackled street clutter by streamlining multiple signs and getting them out of the way (or easily locatable) for visually impaired pedestrians. Information maps installed on the street use the ‘heads-up’ approach, orientated to the users’ direction of travel rather than the usual north/south. The overarching concept, according to Pat Brown, was that ‘the city should put a sublime arm around you and say welcome’. The pedestrian would not necessarily know why they were being aided. It was a physical manifestation of the city helping people find their destination,

allowing them to feel confident to get lost, safe in the knowledge that they would end up in the right place.

Wherever possible, routes guided people to Tube stations from where most other hubs and stations were walkable, encouraging them to explore and access more areas on foot by building confidence in a ‘five-minute walk’ (or 400m) ideal journey model. The wayfaring map system was also designed to help users understand if there will be dropped kerbs and pedestrian crossings along the way –important for those with buggies, disability scooters and wheelchairs. Early consultation demonstrated that fewer strategically placed signs were just as effective as more numerous badly placed ones. Signage with existing provision, such as on bus stops, was adopted, as was positioning some road signage at a lower level where pedestrians could see it far more easily. The aim of the Legible London project is to roll out its consistent and easily recognisable signage across as many areas of

2.

2.

2 Regulations for road signage www.gov.uk/ government/ collections/trafficsigns-signals-androad-markings FEATURE 8

2. Legible London map design © TfL

The wayfaring map system was also designed to help users understand if there will be dropped kerbs and pedestrian crossings along the way –important for those with buggies, disability scooters and wheelchairs.

London as possible. Other global cities, such as New York (see Case Study below) are also creating more legible and consistent approaches to helping people navigate around.

How important is consistency in approach? Road signage and some pedestrian signs are regulated by the Traffic Signs Regulations and General Directions 20162 which provide sizes, font size, minimum clearances over carriageways, footways, shared routes and bridleways. However, a surprisingly large variety of deviations from the standard approaches to design in this field can be seen. There have been a number of zebra crossings installed which employ a range of different colours. I have also seen a good deal of ‘artistic’ use of independent metal studs meant for use as tactile paving. They are sometimes also employed as a non-slip device: tactile surfaces are intended to be an essential safety feature which advise pedestrians who need them on the location of safe crossings.3

back to those local variations in signage that caused all the problems in the past.

And where are we heading now, in this brave new world of technological solutions? Has it allowed us to free ourselves from the mostly visual signage of the past and allowed us to consider other forms of messaging? Why can’t our immediate environment simply tell us what’s going on? With the Talking Lamppost project (a Playable City initiative)4 everything from street furniture to post boxes and cranes becomes interactive, with pedestrians able to trigger a talking response from inanimate objects which can tell them everything from how they’re feeling (yes, really) to inviting dialogue via text messaging about what local area improvements they’d like to see.

3 Guidance on tactile paving surfaces www.gov.uk/ government/ publications/inclusivemobility-using-tactilepaving-surfaces

4 Talking Lamppost project https://www. playablecity.com/ projects/

https://www. mediacityuk. co.uk/newsroom/ talking-lamppostsbecome-a-reality-atmediacityuk/

5 RNIB REACT Talking Sign System

https://react-access. com/

https://www. sightadvicefaq.org. uk/independentliving/transport-travel/ react-talking-sign

https://www. chroniclelive.co.uk/ news/north-eastnews/talking-lampposts-help-blindpeople-1449652

Invented in Japan in 1965, the range of warning surfaces also includes corduroy paving, which has rounded bars in the surface to provide warning of hazard, such as top or bottom of stairs, a ramp, level crossing and so forth. Is it acceptable to play with set standards that some sections of the community vitally need to navigate their way in the world? Do we really find it acceptable for a blind person arriving in a new town to have to wonder what the hell is going on with an artful arrangement of random size studs conveying who-knowswhat, instead of what they need and rely on? Is it right that a visually impaired person is bewildered by whether the art on the road is a right of way zebra crossing, or just a bit of fun or a political statement? There is a boundary somewhere between frivolity and the preservation of safety and life.

Getting this wrong can have serious consequences and I do know blind people who have had major accidents, such as falling onto train lines, because the wrong tactile signage had been used. There is a danger that we could just be going

It’s not just major cities in countries like Japan, USA, Canada and the Netherlands which are having all the fun. Talking Lampposts has also been rolled out in Bristol, Nottingham and MediaCity UK in Salford. Users scan a QR code on a given object and this will prompt an interactive ‘conversation’ via text, with answers to questions in real time. This talking signage also provides users with local information and interpretation about the location. Fun though it may be, this is not an exercise in levity, but also has a serious intent to garner opinion and to help with future development.

The talking signage phenomenon is also being taken to a new level and becoming a permanent wayfinding and information system for people with visual impairment. In Newcastle, for example, the RNIB (Royal National Institute for the Blind) REACT (React Audio Triggering System) Talking Sign System5 has been installed to provide spoken information via speakers attached to lampposts and other features. Users carry an electronic keyfob or use a phone app which triggers the speaker at distances up to 8m away and it provides all kinds of information, from routing and wayfinding to transport times and location details. This has been installed in many transport locations around the UK and the variety of possible uses is clearly enormous and should not

FEATURE

4.

© TfL

3. Legible London wayfinder with map

9

3.

necessarily be restricted to owners of smartphones. Other ‘triggering’

caring about them and wanting to meet their needs.

The next time you’re considering how to impart information to users of any space, instead of just showing them, perhaps consider actually ‘speaking’ to people directly about what they need to know, too. Think

also about other senses such as touch to impart information and understanding. It’s a sign you care about them.

Reference to village names

Village names are already embedded in London’s bus system.

others they are caring for to study maps and timetables in tiny print. It could also feel more relevant and friendly if a local accent or dialect is used in the delivery.

It doesn’t have to be an important countrywide signage scheme that makes a landscape more friendly and hospitable. Little project touches, such as the 3D sign6 made for visually impaired visitors to a walking labyrinth in Seaton, Devon, go a long way to making people feel the environment is

Building better knowledge

We all know from our usual modes of transport that we use our own mental get about. Drivers navigate London by landmarks and, from this, develop an advanced) vocabulary of favoured routes. Tube travellers see London as a collection points, lines and intersections. When cyclists plan their journeys, they think safety, effort and environment.

To create effective support for pedestrians developing their mental maps we

FEATURE

Jill White is a writer and landscape

6.

5. Legible London, A wayfinding study, ‘London’s Villages’ © Central London Partnership

6. South Island, New Zealand © Graham Macey

simplify London in a way that is useful for walkers. London has plenty of memorable

London’s ‘villages’ London has a wealth and named areas, clusters of neighbourhoods distinctive localities. can form a code connect their knowledge.

Changing the culture

10

5.

Darkhorse Design

Founded in 2005, Darkhorse Design is a full service communications agency and content publisher specialising in the built and natural environment.

St Helens Council

The Dream site in St Helens was one of seven chosen from over 1,400 publicly nominated locations for the Channel 4 series The Big Art Project. Working alongside artist Jaume Plensa and local focus groups, Darkhorse created a visual wayfinding system including striking black-and-white imagery to reflect a dream-like state. The site was reimagined to create a sense of local ownership and place with planet positive fabrication of signs using locally reclaimed and repurposed material where possible. Digital aspects include on-site signage with downloadable audio guides, plus augmented reality which is used on-site to show the original mine shafts; visitors can look through their camera phones and watch as the mine shafts appear, transporting the viewer back in time to the working Sutton Manor Colliery.

United Utilities

A wayfinding and interpretation system was required across thousands of acres of regularly used United Utilities land with supporting communications collateral to encourage safe and responsible enjoyment of the countryside. Highlighted points of interest on the maps are brought alive by accessible 3D illustrations that attract attention to the key destination points, and a colour coded system is applied to walks for different audiences. Innovative and sustainable cost-effective signage, sympathetic to their individual surroundings and usage, were plotted across the sites providing local information as well as public safety and awareness messages. Joint venture project between Darkhorse and Sundog Creative.

Bury Council

The Irwell Sculpture Trail, which spans over 33 miles, is the UK’s longest public art trail. It features over 70 artworks by local, national and international artists in rural and urban settings. Its aim is to connect various aspects of the Irwell Valley, its people, its heritage, its parks and countryside using artworks in the environment. We developed a brand strategy following extensive research in both local communities and the tourism marketplace. This cultural project required the delivery of a family of accessible signage to work across a range of locations with varying environmental considerations covering demographically different user requirements. On-site digital interpretation is available with a website providing interactive and downloadable maps, QR codes, mobile apps, on-site audio guides, and sustainably printed seasonal visitor guides.

CASE STUDIES

The overarching concept of Legible London was that ‘the city should put a sublime arm around you and say welcome’. This legacy has led to many developments in signage and mapmaking designed to welcome the visitor. This selection of case studies illustrates current approaches.

1.

2.

3.

1. Dream at St Helens

2. Thirlmere

11

3. The Lookout at Clifton Country Park

Steer

An infrastructure and transport consultancy. The core areas that define the practice are place, identity and movement.

Toronto Natural Environment Trails

Toronto’s forested ravines and natural trails are well-loved and heavily used. As trail usage increases, so do the pressures on these areas, alongside user expectations for wayfinding. In response, the City of Toronto engaged Steer to develop a custom information system specifically suited for the needs of its trails and its users on foot and bike. The system combines wayfinding, interpretation, trail rules/etiquette, and emergency safety instructions into a simple, durable, and cost-effective system of panels mounted to timber posts.

See Paddington

The canal side around Paddington Basin suffers from a lack of visibility, coherence and sense of place. The Paddington Partnership commissioned Steer and Jedco to address these issues. The outcome was See Paddington – a coordinated package of interventions in the form of perforated steel panels that graphically integrate locally inspired stories and public art derived from Paddington’s heritage, community and nature to create a narrative trail linking key gateways with the canal between Bishop’s Bridge Road and South Wharf Road.

STUDY

CASE

4. Trail head and fingerpost © Steer

5. Interpretive panels and painted mural © Steer

4.

12

5.

CASE STUDY

Toronto 360

Toronto’s TO360 wayfinding strategy supports walking as the connecting mode that enables multi-modal transportation in the city. TO360 provides information for pedestrians, cyclists, transit users and motorists through unified signage and mapping. Steer has supported the City of Toronto since 2011 in the preparation and delivery of the system. After successful evaluation of the 2015 Financial District pilot, the project is now being rolled out citywide by the City of Toronto and its project partners including BikeShare, TTC and Metrolinx.

Bankside

Southwark Council and TfL launched a competition to address pedestrian conditions on Lavington Street as part of Bankside Urban Forest. In response, Steer designed a new modular product that enabled widening of the narrow footways to allow more space for people on foot, with buggies or in wheelchairs and accommodate a cycle contraflow. This innovative product demonstrates how streets can be rapidly reconfigured to respond to changing pressures, accommodate increased footfall and support safe movement around construction sites or roadworks.

6. TO360 Fingerpost © Steer

7. TO360 Map sign © City of Toronto 8. Bankside Boardwalk © Better Bankside

6.

7.

6. TO360 Fingerpost © Steer

7. TO360 Map sign © City of Toronto 8. Bankside Boardwalk © Better Bankside

6.

7.

13

8.

City-ID

Information and wayfinding solutions to integrate people, movement and places.

WalkNYC

WalkNYC was designed to help the 8.5mn residents and 50mn visitors a year to walk, bike and use public transit by providing new types of information and a standardised system of parts. It provides an intuitive, legible and extendible information system with an elegant family of products, robust design standards and a confident visual identity, all inspired by New York City and its iconic Subway system.

The project continues to expand above ground and below with the renovation of NYC Subway system as part of the New York City Transit Enhanced Station Initiative.

CASE STUDY

9. Presentation boards © City-ID

10. Product family © City-ID

9.

14

10.

CASE STUDY 11. New York Wayfinding © City-ID 12. Printed maps © City-ID 11. 12. 15

Interconnect Birmingham

Interconnect Birmingham is a partnership and framework initiated in 2006 by Marketing Birmingham (now West Midlands Growth Company) within which infrastructure and design for Birmingham’s city centre streetscape is being evolved and improved, with a focus on people, their journey, interaction and activity. Interconnect delivers an integrated pedestrian wayfinding and transport information system through an innovative research-led approach, focused on improving experiences for residents and visitors of the West Midlands. The mapping and products were updated across the city centre in readiness for the 2022 Commonwealth Games.

CASE STUDY

13. Wayfinding system © City-ID

14. Bus stop wayfinding system © City-ID

13.

16

14.

17 CASE STUDY

15, 16, 17 & 18. City wayfinding system and map detail © City-ID

15.

17.

18.

16.

GreenBlue

Time

For further information on our versatile products visit woodblocx-landscaping.com or telephone 0800 389 1420 Sustainable timber solutions for the built environment with limitless design potential The world’s #1 modular timber system Street Furniture | Raised Planters | Free Design Service LIJ Advert 2023.indd 1 23/3/2023 7:54 pm Provides amenity and biodiversity Creating healthier urban spaces in harmony with nature T: +44 (0)1580 830 800 E: enquiries@greenblue.com W: greenblue.com #MakeAChange Green Blue Smart Space Air RootSpace HydroPlanterReLuminate AQ Planter

Urban’s unique suite of products act as the interface between nature and the built environment.

to

change. 18

make a

Ilford through the lens

A rich photographic heritage has inspired the design of a child-friendly public realm built on the site of the former Ilford factory.

1.

1.

FEATURE

1. Packaging paper in 1894

19

© Courtesy of Michael Talbert ‘photomemorabilia.co.uk’

With an emphasis on child-friendly design, the newest urban quarter in Ilford and one of Redbridge’s largest regeneration schemes was given a resolution to grant planning just before Christmas. Connecting the area’s rich industrial heritage with a relatable and hospitable landscape for children provided a unique placemaking opportunity.

Harnessing the abundance of opportunity that the £18.8 billion Crossrail project is bringing to Ilford, this Telford Homes scheme features 837 new homes and 447 student accommodation bedrooms with 3,500m²+ of commercial floor space, and almost 7,000m² of new public realm. With the potential to set a precedent for future development in the area, this development will mark a significant change of use and improve permeability in central Ilford.

As one of only a few UNICEF child-friendly boroughs in the country, Redbridge Council advised Telford

Homes on a specialised engagement strategy. Chapel Place was named as the pilot scheme within the council’s Child-Friendly Action Plan, and Telford have therefore taken as many opportunities as possible (to date) to put youth engagement at the heart of this strategy. While child-centred design was a key element – with youth ambassadors influencing the design from the outset, framing the engagement process was the industrytransforming innovation that has characterised Ilford’s past.

Celebrating the heritage of Ilford, the design narrative focuses on the former Ilford Ltd (previously Britannia Works Factory) – a photographic plate factory – on which the development is planned. Founded by Alfred Harman in 1883, Ilford Ltd developed innovative photographic technologies including glass photographic plate production, the silver emulsion to create photosensitivity, and film and cameras which transformed the photography industry at the time.

Our design for public realm at Chapel Place was inspired by the innovative technologies that succeeded in putting Ilford on the world map. Concept design sketches were developed, refined and folded into this design narrative. Two concepts based on the fluidity

of silver emulsion and photographic plate geometries were used within the site to help create two distinct areas. The photographic plate concept was applied to an urban linear space which would function as a retail and commercial corridor, while the more curved silver inspired spaces would be more suitable for a central green space (named Britannia Gardens – reflecting a former green space in the factory grounds) that would form the heart of the development.

To strengthen the link with the heritage of Ilford Ltd, its branding and packaging colour schemes of sands, buffs and greys were used to inspire the hard and soft material palette. Intended to reinforce distinct character areas in the site, these paving designs and colours created a natural navigation through the site. Similarly, planting and furniture designs utilised the bright colours of the packaging labels through flower and seed head colours and powder coated accents to the metal work of the furniture.

Enshrined across Redbridge policy is a commitment to children’s rights at the heart of every council decision. With 25% of Redbridge’s half a million residents aged 0–15, achieving UNICEF UK Child Friendly Community status for Redbridge was a key manifesto pledge for the

2. Innovations of Britannia Works factory

© Courtesy of ‘Silver by the Ton: A History of Ilford Limited 1879-1979’

3. Innovations of Britannia Works factory

© Courtesy of ‘Silver by the Ton: A History of Ilford Limited 1879-1979’

4. Innovations of Britannia Works factory

© Courtesy of ‘Silver by the Ton: A History of Ilford Limited 1879-1979’

With the potential to set a precedent for future development in the area, this transit-oriented development will mark a significant change of use and improve permeability in central Ilford.

Pierre Chin-Dickey and James Blower

2.

3.

Pierre Chin-Dickey and James Blower

2.

3.

FEATURE

4.

20

current administration. Redbridge’s Child Friendly Action Plan provides a UNICEF-aligned programme to put children’s educational development at the centre of public space design. Ensuring that key design priorities on Chapel Place were linked to the UNICEF child rights principles was important for framing the public realm and landscape strategy. UNICEF Child-Friendly Cities Initiatives1 explore ways of elevating community voices, needs, priorities and rights of children, allowing them to form an integral part of public policies, programmes and

decisions. The initiative’s practical toolkit based on the seven Principles of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child were used by designers to ensure that at no point in the design process were children an afterthought. Divided into general principles (Life, Survival and Development; NonDiscrimination; and Participation) and human-rights principles (Dignity; Interdependence and Indivisibility; Transparency and Accountability), they ensure a quality of care and provision in children’s lived experience.

For this scheme, we partnered

with UP Projects to empower young people to shape the narrative through both public art and infrastructure. Using the photographic heritage of Ilford Ltd as a lens to frame engagement, workshops included meeting local Ilford artist Andrew Brown to look at Ilford Ltd’s heritage items and explore photographic techniques.

This strategy provided an opportunity for an emerging neighbourhood to connect with communities both old and new as the project started to take shape. It allows

FEATURE

5.

6.

5. Proposed Britannia Gardens’ allocated open space

© Image courtesy of Rockhunter 6. Proposed Britannia Gardens’ allocated open space

21

© Image courtesy of Rockhunter

art and creative practice to sit at the heart of this development and gives people the chance to develop what and how this cultural offer might shape and deliver tangible social value to both young people and adults.

This philosophy remained at the heart of the strategy and design of Chapel Place. Structuring engagement sessions with activities for young people to participate in led to helpful design responses that the design team could incorporate, such as space promoting digital arts innovation and a community hub to access digital art

technology.

Seeing how photography could inspire young people, Ilford’s photographic heritage played a key part in devising Chapel Place’s play strategy, with the design of individual features inspired by different photographic key principles: perspective, light, texture and colour. These features include a silver-themed climbing feature; picture frame-inspired play features; brightly coloured play items representing the packaging materials; and iridescent objects that play tricks on the eye by shifting

with light and shadow. Similarly, it was determined that any public art should, as well as reinforcing historical narratives, be functional and used for play or seating.

While these principles framed the design approach, implementation of child-friendly design has to be relevant to the context. Harnessing the lived experience of Redbridge Youth Ambassadors through engagement gave children an opportunity to shape placemaking strategies and ‘places’ where they feel connected. The crux of the challenge with Chapel Place was to make the powerful heritage relevant to the modern youth perspective, in so connecting the past with the future.

As placemaking specialists, creating successful public realm can create a multitude of challenges and

FEATURE

https:// childfriendlycities.org/

1

7.

8.

7. Ilford Community workshop activities

© Copyright Up Projects Consultation Curator and run by local artist Andrew Brown.

Photo by Bronwyn Jones.

8. Photographic plate production concept sketch

9. Camera aperture concept sketch © Courtesy of Michael Talbert ‘photomemorabilia.co.uk’

10. Packaging paper in 1894 © Courtesy of Michael Talbert ‘photomemorabilia.co.uk’

9.

22

10.

While Chapel Place is inspired by the past, the engagement with local young people has shaped a relevant design for the future.

overlooking young people can limit success. Young people demonstrate energy and dynamism that should be nurtured and catered for. While Chapel Place is inspired by the past, the engagement with local young people has shaped a relevant design for the future. As Chapel Place has already been given a resolution to grant

planning, moving forward into the next stages of design, its future success hinges on ensuring these young voices are heard.

Client: Telford Homes and Sainsbury’s Team: HTA Architects (Lead Consultant), UP Projects (Public Art and Consultation), Mayer Brown (Transport), Ramboll (Engineers)

12

FEATURE

Pierre Chin-Dickey CMLI, CLARB, LEED A.P. is a landscape architect and Design Director at Macfarlane + Associates

James Blower MA – Urban Designer and Sustainability Lead at Macfarlane + Associates

11. Aspirational townscape sketch depicting the development and changing Ilford context

© Image courtesy of HTA Design

12. Proposed Chapel Way Winston Way Gateway

© Image courtesy of Rockhunter

23

11.

They’re back!

Two popular sandstones have returned to our Commercial sandstone range.

Both sandstones are as strong as they are beautiful, meaning they can be deployed in heavily trafficked areas and withstand the test of time. This strength, combined with the size of the quarried blocks also means they capable of creating even the largest bespoke furniture items.

Visit: marshalls.co.uk/commercial

to start designing with Marshalls sandstone

SANDER RED

Choice and versatility from the Marshalls sandstone range

BROWNRIDGE

BRACKENDALE

THORNLAKE

Laurel Bank: Hawks View:

a former best-seller, with beautiful, smooth creamy tones.

a stunning dual-colour available in 4 finishes.

Blasted FlamedClear blastBush hammered & brushed

Blasted FlamedClear blastBush hammered & brushed

New New

Blasted

The hospitable bollard

Ross

Bollards: you can’t sit on them; they don’t help with litter and they bar your way. Some even carry self-important branding telling you who’s in charge. In many situations, bollards can be positively hostile: hard lines of metal, clearly intended to prevent movement.

So, compared to other pieces of street furniture, can bollards be described as ‘hospitable’?

The City of London is a good place to contemplate this question. With a long history of installing ‘posts’ in its streets, today the City is a bollard hotspot. Wherever you stand in the

1. A Culture Mile bollard All images © Cathy Ross

When it comes to contributing to a city’s history, bollards have a clear role to play, acting as reminders of an ever-present past.

1.

FEATURE 26

Cathy

3.

Square Mile, you will probably spot a bollard or two. All types and sizes are here from modern, impact-tested, steel cylinders to ancient cast-iron boundary posts marking parish land. By far the most distinctive designs are the two bollards associated with the Corporation of the City of London, the Square Mile’s governing body. What’s now termed ‘the D3 type’ first appeared in the 1820s, when it was a ‘flat post’. More showy is ‘the C3 type’, formerly known as a ‘guard post’, and dating from the 1860s. With its black-and-red livery, octagonal body, lemon squeezer top and star collar, the C3 is a slightly pompous presence. The basic design has been much tweaked over the years. Variations on the theme include the thin, dainty B5 which arrived in the 1980s to fill the holes in the ground left by parking meters; and a modern streamlined, high-security C3 whose heritage exterior hides an

inner core of crash-proof steel.

These hard-core C3s are the latest addition to the City’s bollard population and they arrived along with growing anxiety about terrorism. Over the last 20 years or so, bollards have become ‘hostile vehicle mitigation’ measures in ever-increasing numbers. The new arrivals no longer carry the coat of arms of the City of London, so have a more forbiddingly anonymous look. Standing in long lines around significant buildings, these are the grey squirrels of the bollard population: invasive displacers, now the dominant species.

So, are City-branded bollards hostile or hospitable? Despite the association with terrorism, I’d come down on the side of hospitable – with the proviso that bollards elsewhere may have different stories to tell. Here, however, I’d suggest that what makes bollards hospitable is their potential

to be playful. Maybe it’s something about their scale and appearance, but City bollards do seem to have a rather silly side. They can easily be given a personality by placing a hat on their head; and the tendency of odd singletons to move around the City, popping up in the pavements or disappearing, seemingly at random, gives them a kind of agency. This playfulness encourages interaction. Stray hats aren’t the only things that bollards attract. City bollards bear all sorts of gifts – scarfs, gloves, the inevitable drink cans. Their hospitable qualities extend to hosting stickers: a few summers ago, many City bollards evidently joined Extinction Rebellion. On its website, the World Bollard Association underlines the ability of bollards to add imagination and humour to the public realm. In the City, the Corporation requires its public realm to have a certain gravitas (‘safe,

Over the last 20 years or so, bollards have become ‘hostile vehicle mitigation’ measures in ever-increasing numbers.

FEATURE

2.

2. The D3 bollard

The hard core revealed

3.

27

high quality and inclusive’), which mitigates against the wacky end of playfulness. However, the one aspect of bollards that seems to be tweakable is colour. Bollards in Leadenhall Market are painted in rich shades of plum, while those in the City of London Cemetery are green. In 2016, the City promoted its ‘Culture Mile’ strategy by wrapping some bollards in a colourful vinyl sleeve designed by Richard Wolfstrom. Does the future promise more colour for official City bollards? Given that the Corporation regularly repaints its bollards to freshen them up, this is at least a possibility. On the seafront at Margate is a rogue Corporation bollard, a seaside day tripper painted a rather stylish bright yellow. Apart from playfulness, the oldfashioned design of the C3 may also add a hospitable note. As the City’s new office blocks become bulkier, taller and more hard-edged in mood, so the faintly ridiculous 1860s items

at ground level acquire a new allure, indeed a new softness.

To 1960s modernists, fauxVictorian street furniture was shamefully backward-facing. Today’s planners seem to hold more nuanced ideas about the contribution historic character makes to a sense of place. And bollards have a clear role to play here. Small reminders of the everpresent past, they perhaps also add some sense of reassurance about the future for people who brush past daily – residents, workers and visitors alike.

‘The City bollard is an indisputable symbol of the City of London,’ said the Corporation’s Annual Report in 2005. Nearly 20 years later the City has changed, as has the detail and role of the bollard. But they remain familiar and, to my mind, friendly parts of this particular urban landscape.

Bollardology: observing the City of London, by Cathy Ross. Quickfry Books, 2022. ISBN 978-1-39992123-7. £12.99. Available from the Guildhall Art Gallery shop and online.

As the City’s new office blocks become bulkier, taller and more hardedged in mood, so the faintly ridiculous 1860s items at ground level acquire a new allure, indeed a new softness.

Cathy Ross is a historian and author

4.

Cathy Ross is a historian and author

4.

28

4. Hostile bollards? © Cathy Ross

Newhaven’s Wayfinding and Signage Spatial Masterplan

Newhaven has a commitment to creating an inclusive environment by ensuring that all aspects of an area’s wayfinding and signage are carefully investigated and planned.

Newhaven is a small East Sussex port town with a population of 13,000 people lying at the mouth of the River Ouse. The local authority, Lewes District Council, received funding of just over £5mn from Government’s Future High Streets Fund (FHSF) and Newhaven Town Deal funding to ‘re-connect the

Town’. The FHSF ‘Re-imagining Newhaven’ prospectus provides a foundation of baseline information, analysis and overarching themes to help deliver some big ideas and aspirations for the town.

The prospectus acknowledges Newhaven’s poor public realm and the fact that there’s little sense of arrival

FEATURE

1. Cover page of final report © Credit Lewes District Council

Marc Tomes in conjunction with Lewes District Council

29

1.

when entering the town from transport interchanges, and by the severance caused by the river, railway corridor, industrial estates and existing road network. The ring road known locally as ‘The Collar’ is a particular issue, effectively cutting off the town centre from its surroundings. Like many towns, a past emphasis on traffic planning and engineering has led to the dominance of cars, an infrastructure that does not lend itself to pedestrian or cyclist movements and a town centre that ‘turns its back’ on its surroundings.

Over time, notions of civic pride have eroded along with the quality of public realm, further diminishing the sense of place and amenity value. The furnishings and materials are repaired and added to in an ad hoc manner, leading to increased clutter and visual discontinuity.

One of the threads emerging from the prospectus is to improve wayfinding and access across Newhaven, to reconnect the town

centre and the high street with key residential and business areas, increasing footfall and dwell time, while reducing traffic and improving air quality. Key to achieving this aim is to create clearer, more legible and engaging routes that simultaneously promote local identity and enhance public realm.

Lisa Rawlinson is Head of Regeneration at Lewes District Council. ‘The desire was to install new signage at key access points and gateways to the high street including from the railway station and through to riverside walks,’ she says. ‘This required a strategic approach to working out where to put this and what this might look like to help create something that reflected Newhaven’s unique characteristics.’

Lewes District Council engaged landscape architects, Allen Scott, to prepare a Wayfinding & Signage Spatial Masterplan for Newhaven, to deliver a pilot scheme for new visitor trails along the river, and to spark

interest in Newhaven’s heritage.

‘As landscape architects, we wanted the spatial masterplan to be a comprehensive approach to wayfinding and signage for the whole town, taking a holistic and spatial view of movement and inclusive access and to use it to deliver some of the emerging ideas for the town,’ says Marc Tomes, Allen Scott’s Director.’ Ultimately, the Spatial Masterplan needed to improve people’s experience, making the town easy, safe, convenient and attractive for people to find their way around and to spend more time there.’

Following contextual analysis, the project team undertook consultation with a number of key stakeholders including East Sussex County Council, Newhaven Enterprise Zone and Newhaven Town Council. This framed a structured methodology based around four steps involving research and site visits, targeted workshops and presentations and initial conceptual illustrations of potential outcomes.

2. Reconnecting the town centre by improving connections to the high street © Allen Scott.

The project highlighted to us all that wayfinding isn’t just about signs. It’s about how people experience a place or a journey.

FEATURE

2.

30

The ethos behind the Spatial Masterplan went far beyond considering replacement signage. It resulted in helping to set the scene for vital and necessary improvements to the public realm across Newhaven.

The content of the masterplan covered town-wide wayfinding principles, locations for wayfinding and signage improvements and better visual language and potential materials. Using these principles, the team then defined specific improvements in key locations across the town and prepared an action plan.

Says Rawlinson, ‘The project highlighted to us all that wayfinding isn’t just about signs. It’s about how people experience a place or a journey.’

Combining these concepts demonstrated that the experience of a ‘place’ involves a number of factors, including the physical environment of the public realm and the elements and activities within it. Together these provide both intuitive and informative navigation, leading to a better sense of that place. This leads to connections that are more positive between people, places and each other, encouraging active and healthy lifestyles and reducing air pollution through a reduction in car use.

‘The ethos behind the Spatial Masterplan went far beyond considering replacement signage. It resulted in helping to set the scene for vital and necessary improvements to the public realm across Newhaven,’ says Rawlinson.

‘We kept coming back to the town’s distinct character, a juxtaposition of marine, coastline, countryside and industry within such a small geographic area, and our desire to reflect and respect this in our design response,’ says Tomes. ‘We felt it was important to ensure the essence of Newhaven, its history and evolution, for better or for worse, was not lost to homogeneity but that emerging projects and actions followed principles to preserve the character while enhancing the amenity

of the local community and visitors alike. The pragmatic starting point, though, was that the current quality of the public realm and amenity spaces is poor with tired infrastructure in need of investment.’

Before embarking on the action plan, the team sought to gain a deeper understanding of how people currently make their way through the town and to what extent these could be rationalised and improved. Primarily through personal observations, available visitor data, footfall data and consultation, Allen Scott analysed the various visual cues and physical elements such as public realm furnishings materials, signage, public art, vegetation, buildings and infrastructure that impart the current ‘sense of place’ and amenity value to help unpick the challenges and inform potential solutions. In Newhaven’s favour is its geography, topography, river, coast and proximity to the South Downs National Park, which all help with intuitive orientation. Long views towards the town centre and the river from the east, west and south and panoramic views from Castle Hill and the fort provide a valuable sense of where you are within the wider landscape. The town centre and high street currently suffers from severance to the river, the coast, the South Downs National Park and to its residents. The analysis reinforced outcomes and recommendations from previous studies to improve the

navigation and connectivity for all abilities and all ages. This included enabling ease of movement and connections for people who are visually impaired.

Applying best-practice principles to this analysis with more specific principles for Newhaven provided two overarching directions, better arrival and destinations and better routes and pause points. Derived from the research and discussions, the team then applied four themes to assist

FEATURE

4.

3. Newhaven railway station, one of the key gateways into Newhaven

© Allen Scott

4. Contextual analysis included spatially mapping baseline information

© Allen Scott

5. Opportunities identified include improved gateways, routes and places to stop across Newhaven

© Allen Scott

3.

31

5.

in formulating specific projects and actions. These were: re-imagining the sense of arrival into Newhaven; reconnecting the town centre; reestablishing relationships between land, river and sea; and repurposing under-utilised spaces. Best practice principles include wayfinding that’s inclusive, relatable, simple and legible. Newhaven’s town-wide principles include wayfinding that is well-placed and integrated, consistent and coordinated, and in the context of the Towns Fund and FHSF improved wayfinding could also act as a catalyst for further enhancements and positive change.

Under these themes, 33 projects

were identified and organised, each one located and described with a number illustrated and expanded upon. Importantly, the Spatial Masterplan included a series of recommended actions to help deliver it. These include strategic and aspirational improvements such as major enhancements to the Transport Interchange Hub (ferry, train, bus interchange) through to quick wins of decluttering and rationalising signage and furnishings. There are also recommended overarching actions and projects such as gathering coherent content about Newhaven, its past and present, and formatting this in a way so it is easy

to use for future information boards, website information and public realm enhancements. Grouping the actions into the four themes enabled the team to demonstrate how specific issues can be resolved through physical improvements, although many proposals also deliver multiple themes and benefits. Priority ‘early win’ pilot schemes were identified that would deliver the objectives set for the project as well as objectives set within the Town Investment Plan. Working with Newhaven Historical Society, a heritage interpretation trail has been created along the River Ouse. The new bespoke information boards reflect the visual language and materials palette of Newhaven. They also include QR codes linked to further information about Newhaven and its heritage.

Says Rawlinson: ‘The Spatial Masterplan includes several ambitious “Big Idea” projects aimed at addressing issues that go far beyond just wayfinding.’

Prioritising projects for the longer term is challenging without further planning, design and engagement with stakeholders. To assist with this, the report included an assessment toolkit to help council officers and their partners prioritise projects based on success criteria.

The Spatial Masterplan sets out an ambitious and holistic way to deliver improved wayfinding across Newhaven over time. Some

The Spatial Masterplan includes several ambitious ‘Big Idea’ projects aimed to address issues that go far beyond just wayfinding.

FEATURE

6.

6. Conceptual ideas for a family and a hierarchy of bespoke signage © Allen Scott

32

7. Principles, overarching directions and themes for application help deliver a reconnected Newhaven © Allen Scott

projects will take far longer to deliver than others, but the more complex projects are broken down into a series of smaller manageable projects to simplify staged delivery.

It was not the purpose of the project or the report to propose a complete ‘materials and furniture palette’ for Newhaven. However, in the interest of steering a consistent

and coherent approach to future public realm improvements and wayfinding interventions, the Spatial Masterplan report included the principles applicable to material specification.

The report also insists that integrated sustainable approaches to design, specification, implementation, ongoing management and maintenance are part of the solutions,

actions and interventions. This includes sustainably sourced products and materials, environmentally sensitive designed solutions that provide benefits to biodiversity and climate action, integration of appropriate vegetation to help with air quality control and reduce the heat-island effect, potential for sustainable drainage solutions such as rain gardens, swales and permeable paving and information and interpretation that explains climate change and the biodiversity crisis.

Newhaven’s Wayfinding and Signage Spatial Masterplan was adopted by Lewes District Council and signed off by the Town Deal board in 2022. An initial pilot scheme is due to be implemented this summer.

Marc Tomes is Director of Allen Scott and a High Street Task Force Expert. He has more than 20 years’ experience working within the landscape and environment sector in the UK, Australia and New Zealand

FEATURE

8.

9.

8. Conceptual ideas for improving one of the key gateways by applying the Spatial Masterplan principles, direction and themes

© Allen Scott

33

9. Conceptual illustration of a ‘Pause point’, applying Newhaven’s family of signage and materials © Allen Scott

Elephant Springs Eternal

A £4 billion redevelopment programme has seen radical change in South London. It’s hoped that a new two-acre park will prove an iconic draw for generations to come.

34

1.

We looked at how we could create biodiversity in any residential areas, as well as the park itself.

Alice Charles

In South London, at the heart of one of the capital’s busiest routes, sits a ‘little oasis’, Elephant Springs. Opened last summer, the distinctive ‘pocket park’ has proved a draw for hundreds of people across the city. Elephant Springs is part of Elephant Park, a mixed-use development by Lendlease and Southwark Council, which when completed will offer 3,000 new homes, 50 new retail spaces, a library, heritage centre and nursery. There are also plans for a new office building and an NHS community health hub. The development is scheduled for completion in 2026 with a bold ambition of achieving net-zero operation by this time.

Elephant Park itself is intended as a ‘community space’, with rain gardens and walkways, and forms part of a £2.5bn plan by Southwark Council and Lendlease to boost the local economy.

Nearly 15% of people who live in the borough are estimated to earn less than the living wage and Southwark has the sixth-highest rate of child poverty out of all local authorities in the UK.

Zena Wigram is Head of Marketing at Gillespies in Clerkenwell, London. The project has been ‘a long time coming,’ she says. Previously, the company had completed a number of major projects in Southwark, including a public park for the apartment and

workspace complex Bankside Yards, a landscape courtyard for the office development The Forge, as well as ITV headquarters and the park at the apartment complex, the Biscuit Factory in Bermondsey.

For the Elephant Park development, Gillespies was retained by Lendlease back in 2014 to devise a masterplan, covering 28 acres, including a new two-acre park. ‘It’s a big footprint,’ she says. ‘We looked at how we could create biodiversity

FEATURE

3.

1. Porphyry quarry Albiano, Nr Trento, Italy

© Hardscape

2. Mel Chantrey among the Porphyry in Italy

© Hardscape

3. Elephant Spring complete © Hardscape

2.

35

There was also a story about play and what we could provide.

in any residential areas, as well as the park itself. There was also a story about play and what we could provide.’

After the pandemic hit, this idea of including a ‘playscape’ for local children became central to the project’s development, and Gillespies describes Elephant Springs as ‘a rocky water-world of fountains, waterfalls and sandy beaches created from 300 tonnes of Italian porphyry stone. Elephant Springs is … a tactile space designed to delight, challenge and excite children and adults alike.’

During the pandemic, how we use public spaces came under sharp focus and the company undertook a lot of research, looking at how water and sand could be used in the Elephant Springs project, which sits at the heart of one of London’s busiest routes, providing a respite from the heavy traffic.

Neil Matthew is Senior Associate at Gillespies but when the project began nearly ten years ago, he was Senior Landscape Architect and has seen his career progress as the project reached completion. ‘I was leading the team, public consultations and client meetings,’ he says. ‘It was a very collaborative process.’

When the project started, a steering group was formed called the Park Action Group (PAG) made up of local residents and professionals who met regularly and acted as a ‘sounding board’ throughout the design process. They were found by posting notices up on the site. ‘It was important to have resident input as the park was next to existing properties,’ says Matthew. The company was charged with developing a focal point for

Elephant Park, which was delivered in two phases, protecting the site’s existing mature trees and adding new ones to provide a canopy, as well

as a wildflower meadow to act as a ‘welcome’ to the area.

Trying to complete the project during lockdown required a change in their way of working. Says Matthew, ‘Obviously, we worked remotely most of the time. But we all know each other well and that made things easier. It was easy just to pick up the phone, and a lot of site visits were conducted virtually via video calls.’

For the park’s water feature, the company worked with artist Mel Chantrey from the Fountain Workshop. Chantrey had previously worked with Gillespies on a larger water feature project in Woolwich, London, called the Royal Arsenal Riverside Waterfront in 2016. Chantrey also designed the

Trying to complete the project during lockdown required a change in their way of working. Says Matthew, ‘Obviously, we worked remotely most of the time. But we all know each other well and that made things easier.

FEATURE

4.

4. Porphyry in Albiano quarry, Italy, selected for the project © Hardscape 5. Watercolour drawing © Hardscape

5.

36

waterscape for the Diana Princess of Wales memorial playground in Kensington Gardens. ‘He was the natural choice,’ says Matthew. ‘He’s a great collaborator.’

For Chantrey, whose background is in fine art, Elephant Springs was a real labour of love. ‘I grew up in the Pennines, wandering about springs and streams, and that became the narrative that informed this project,’ he says. Chantrey learned that there had previously been a watercourse

on the site and had the idea of creating a water feature. ‘The water would emerge from the ground into a tumbling watercourse, ending in a kind of delta, and the course would change colour as it ran through. I had everything hidden, even the drains, so that it looks natural.’

Having previously travelled to a quarry in northern Italy for the project in Woolwich, Chantrey was introduced by Hardscape to the colour and finish of porphyry stone, selected

for its durability and beauty. ‘I don’t use computers,’ he admits and so produced hundreds of drawings, which in the end proved invaluable. He also spent 18 months making precise Plasticine models to scale in Gillespies’ offices. ‘I knew exactly how it would work,’ he says. ‘And I wanted it to be inclusive so you can get wheelchairs in there, you can play with jets. But it’s not just for children, it’s also for adults.’

A presentation to Lendlease went well and Chantrey’s models, drawings

Plasticine model of mound 1 and 2. Mel Chantrey

3D model by Hardscape rendered to show colour variation.

Mound 1 nearly complete. Test layout in Italy. Hardscape

Mound 2 laid out in Italy complete.

FEATURE

Hand watercolour impression and vision. Mel Chantrey

Planning the project

Design view to the north. Lendlease Porphyry paving with jointing material test colour. Mel Chantrey

Paving between mounds and beginning of laying on the project site. Mel Chantry

Elephant Springs porphyry design in construction. Lendlease

37

Water feature paving and porphyry blocks being laid with 5M ‘bridge stone’ (in one piece) in the background. Lendlease

and equipment were shipped to Italy, but just as the project was about to go ahead, the pandemic hit – with the Italian village where the family-owned quarry was located in the epicentre of the outbreak.

Weeks passed and it was eventually decided to work remotely. Cameras were mounted overlooking the quarry yard with round-theclock access so that Chantrey could see what he was doing. ‘I worked every day, from 7am to 6pm, from September to December. It had to be done by Christmas before the snow came,’ he says.

The process was long and involved. For every stone to be used, three or four had to be selected. Says Chantrey, ‘Porphyry is a volcanic rock; a slab can be half a metre thick. I was looking for colour – it was like doing a jigsaw puzzle long distance. In the end, 70% of the product was built in Italy. It sounds crazy, all the odds were stacked against us, but it worked like a dream.’

Chantrey is full of praise for the Italian family that helped bring the vision to life. ‘These guys are artisans,’ he says. ‘It was an incredible working relationship. They ended up adopting me.’

Lendlease had originally intended for the work to be recreated in a field in Kent before being transported to site but having lost several weeks due to the lockdown, the stones were shipped straight to the site itself.

Again, it was necessary to work remotely with cameras set up on site and Chantrey ended up giving the engineers and construction crew a half-day ‘creative induction’, featuring his many drawings and models.

‘People went the extra mile,’ he says. ‘It was a crazy bit of work but so much care has been lavished on this thing –the workmen really upped their game.’

Mathew Haslam, director of Hardscape, has known Mel Chantrey for more than 20 years and had a 30year relationship with Gillespies, since the company first formed. He was involved in early discussions about the project. ‘Mel built an amazing model,’ he says. ‘The digital world doesn’t bring a project to life in the same way. People may sneer at anything old-time, but I think they [Lendlease] fell in love with the Plasticine model.’

But the project was not without its issues. ‘Because of Covid, there was real uncertainty about how it was all going to turnout. It was difficult to predict,’ he says. ‘Porphyry is granitic. It comes out of the ground in sheets, not in blocks. With a digital model, you couldn’t predict the stone height or dictate water flow. It required a leap of faith – and a real team effort with construction team P.J. Careys Ltd.’ Lifesize models were created in the quarry, which required each slab to be numbered and a GPS coordinate assigned, so that each piece could then be reconstructed in London.

An independent risk-benefit

analysis was carried out by the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) on site when the project was 80% completed, and then another assessment was conducted just prior to the park opening in June 2021. In the interim, the company undertook ‘slight changes’, which in the end won the company an award. Mathew is very positive about this process. ‘It’s always good to be recognised,’ he says. ‘It was a feast of innovation.’

Would he undertake such a project again? ‘Oh yeah,’ he replies without hesitation. ‘In Mel, we had someone who wants to reinvent Hadrian’s Wall, the Italians were proud of their material and Lendlease didn’t waver from their vision. It was a real human endeavour. The best projects are a real challenge and produce the best result.’

Meanwhile, when lockdown finally lifted, and Chantrey could travel from his home in Manchester, he visited Elephant Springs and spent some time speaking to the people who had come to enjoy the space. He is delighted with the outcome.

‘The opening was fantastic,’ he says. ‘You’re not sure how things are going to work until the public are there. I saw people on the Tube coming with buckets and spades, and the sound was terrific. For me, it’s a real success. People have come back together, a new community is forming. During the day, I saw families with children playing, people having lunch, and I talked to people in the evening. It wasn’t originally meant to be a playground; it was a “peoplescape”, but it also accommodates the people who had been displaced from Heygate Estate [demolished ten years previously]. The park provides the glue, putting a community back together.

‘It doesn’t look like a playground, it’s a lyrical, romantic landscape – at night the lighting is beautiful. It could have been an abject failure but it worked. It was extraordinary.’

©

People have come back together, a new community is forming.

FEATURE 7.

Alice Charles is a London-based journalist.

38

7. Design view to the south

Lendlease

The Experience Book: For Designers, Thinkers & Makers

The Experience Book examines the design and making of experiences that define the spaces where we live, work and play. Landscape showcases two projects.

On Paradise City

The idea behind The Experience

Book is a simple one. With the evolution of humans as a cultural and technological species, we have become increasingly adept at putting our ideas into the world. At the same time, the word ‘experience’ has been used to sell everything from theories on a new economical era to toothbrushes to holidays to whole cities. A guide to and source of examples of the designed experience, the book is an attempt to (re)anchor ‘experience’ as being fundamental to what it means to design, for better and for worse.

Skaters worldwide have brilliantly subverted the privatisation of public space. This repurposing of what the artist Nils Norman calls the ‘vernacular of terror’ is taken to its wonderfully logical endpoint in Malmö, Sweden. It’s not perfect, but it’s a prototype for how we might go about designing our public spaces from grassroots up and in the interests of all.

On Kids with hammers

Health and safety has become the designer-in-chief of what it means to be socially responsible. This is especially true of how we treat our children, who must suffer our fear for their health and their safety. The

Land and other similarly risk-tolerant adventure playgrounds are a fightback in the name of today’s children, who are being denied the very things – the freedom to experiment, to be hurt, to fail, to test their bodies – that were the making of their parents and grandparents.

PARADISE CITY

A vernacular of inclusiveness: how a city reinvented itself as a skateboarding mecca

Modern concepts of ‘public’ and ‘space’ are easily read (if we take the time to look) in the design of our public realms, whether controlled by public or private bodies or both. The escalation of defensive or hygiene programmes

FEATURE

Adam Scott and Dave Waddell

©

Creative commons licence

1. Skatepark, Malmö, Sweden

Maria Eklind

1.

39

and hardware – mosquito alarms, anti-homeless spikes, pay-per-minute benches, pavement sprinklers, and so on – is the ‘vernacular of terror’ that the artist Nils Norman says is exercised against those we consider not us: the ‘destitute’ and the ‘anti-social’.

It’s not like this everywhere, however, and especially not in the Swedish city of Malmö. Unusually for a long-winter destination, Malmö is a skateboarding mecca, the design of the city’s skate-friendly public realm the result of a long partnership between the not-for-profit skaters’ association Bryggeriet and the municipal authorities. It wasn’t always this way – Malmö’s council was once much the same as city councils the world over, either shepherding skating into acceptable spaces or demonising it as a public nuisance. However, unable to ignore the association’s reactivation of spaces otherwise left to rack and ruin, it donated the site of a decommissioned brewery, and in doing so changed the fortunes of a city that had never fully got over the collapse of its shipbuilding industry.

The details of the role the association and skating in general played in the regeneration of Malmö are a story for another time. Suffice it to say, it has evolved considerably. At the beginning, it was all about what the city could do for skating; today, it is all about what skating can do for

the city. The result: a vernacular of inclusiveness, designed by the once excluded.

KIDS WITH HAMMERS

The world’s greatest playground and the department of health and safety is not invited.

The Land is a small and fenced-off piece of land in a housing estate in north Wales. You could be forgiven for mistaking it for an illegal dump. Tyres and pallets lie scattered across the site. A small stream is full of junk. A large piece of green tubing hangs from a tree. Makeshift seating and the remains of fires betray signs of human activity. It’s what you’d hope your local authority would classify as a health

and safety hazard, and certainly not anywhere you’d bring the kids.

Only, it’s not a hazard; it is exactly where many of the estate’s children play, and everything you see is actually meant to be here. That’s because The Land is an adventure playground, ‘a space’, as it says on its welcome sign, ‘full of possibilities’, and which – in the hands of a band of ever-present and yet unobtrusive playworkers –is wholeheartedly devoted to the business of risky play, including lighting fires, climbing high, hammering nails, and sawing through anything except each other. It’s hardly a new concept, but still an almighty breath of fresh air in an age of stranger fear, hover parenting and internet pervasiveness.

The Land is one of a growing number of such playgrounds, all of which are descended in one way or another from Copenhagen’s wartime ‘junk playgrounds’. Just as the Danish landscape architect Carl Theodor Sørensen was inspired by the creativity of children’s play on bombsites, so it is continually informed by its organisers’ observation of the children it serves. It’s a place of possibility, directed by children for children. Take the kids: it’s wonderfully dangerous.

The Experience Book: For Designers, Thinkers & Makers is published by Black Dog Press.

The Land is one of a growing number of such playgrounds, all of which are descended in one way or another from Copenhagen’s wartime ‘junk playgrounds’.

FEATURE

2.

3.

4.

40

2, 3, 4 Children playing on the Land © Land Plasmadoc

A 100% FSC Manufacturer www.factoryfurniture.co.uk design+ make+ collaborate

A new podcast from Landscape and Open City. Available on: Listen to Talking Landscape 41

Photo - Macgregor Smith Quay Loungers in FSC Redwood and galvanised steel

Gramer Haor –helping a village to grow sustainably

Two years ago, Landscape showcased the collaboration between Birmingham City University and Shahjalal University of Science and Technology. The Prince’s Foundation which supported the project and the academics involved provide an update.

Background

The Gramer Haor Co.Lab was initiated during the summer of 2019 to explore

ways to support sustainable growth of the village of Kazir Gaon in Bangladesh. Kazir Gaon was experiencing rapid growth and expansion, which was occurring in haphazard, unsustainable ways. To tackle these issues, an international partnership was formed between Eccles Ng, Course Director for BA (Hons) Landscape Architecture and BA (Hons) Landscape Architecture with Urban Design at Birmingham City University (BCU), Kawshik Saha,

Associate Professor, Department of Architecture at Shahjalal University of Science and Technology (SUST), and Abubokkar Siddiki, a British Bangladeshi architect. The support of The Prince’s Foundation and use of its Rapid Planning Toolkit (RPT) were integral to the Co.Lab studio. The RPT is a four-step process designed to guide a multidisciplinary approach in the inclusive planning and design of rapidly growing cities and towns.

Following the success of the process, the local government informally agreed to allocate approximately 2.5 acres of land to develop a community hub, which would provide facilities for Kazir Gaon residents.

1. Group photo following the community workshop in January 2022 © Naimul Islam

UNIVERSITY BRIEFING

Eccles Ng, Abubokkar Siddiki and Victoria Hobday

1. 42

1

The Co.Lab continues to be an important opportunity to apply the RPT in Bangladesh and for students and stakeholders to learn through their involvement in a live project.

Project evolution

Given the nature of the location and culture, the RPT activities were adapted to suit Kazir Gaon’s village setting. This bottom-up approach and engagement with villagers and local stakeholders helped build trust with the panchayat (village council) and villagers, which ensured their permission to pursue the project in their village. The initial intention was for the students to work together in Kazir Gaon to develop a collaborative plan for sustainable growth.

Season One – January 2021

With the BCU team not able to travel because of the pandemic, the first cohort of Gramer Haor Co.Lab from SUST made visits to Kazir Gaon, toured the village and met with villagers in small groups to gather information and data. The first cohort worked on the masterplan of the village, including the bazaar, Bhumin (social housing area) and the old village. Their brief was to look at how the village can grow sustainably. The vision emerged through conversations with students,