6 minute read

Experimental techniques

from April 2020

Are landscape architects in the region playing it too safe with planting palettes?

By Charles Lamb

Advertisement

The extreme climatic conditions experienced in the UAE presents a challenge for those creating plantings in the public realm: how to manage the competing elements of commercial clients for a ‘green’ landscape, whilst also considering the environmental implications of continual irrigation requirements. Yet the native flora of the UAE can provide a solution to this dichotomy, enabling a climate appropriate planting palette which, if coupled with sensitive design and a certain degree of re-education, has the ability to create public realm plantings that provide moments of seasonal delight, a more environmentally sustainable maintenance regime, and planting that intrinsically speaks of the place it is from and situated in.

That doesn’t mean that landscape architects and designers are limited to UAE natives, rather they can draw on a planting palette from areas of similar climatic conditions worldwide to create highly ornamental, yet more sustainable, public plantings. To fully understand the structure and ecological function of varied plant communities, there is no better way than exploring their natural habitat. Since the UAE is home for us and we have an abundance of native flora and fauna, we will start here. The recent heavy winter rains provided ideal conditions for exploring plant communities in the wild and we saw an explosion of wildflowers as a result. The wadis around Jebel Jais in Ras Al Khaimah have been carpeted by soft pink flowers. These expanses of Erucaria hispanica, erupting from a dormant seed bank, provided not only a seasonal spectacle but also inspiration for temporal elements of the landscape that could, with imagination, be re-created in the

public realm. Often growing in the mixture of coarse rubble on a wadi bed, such growing conditions could be replicated in designed landscapes with a similar, manufactured planting medium to create a low nutrient base to encourage shorter, but more climatically resilient, vegetation. The effect would be visually stunning, creating seasonal changes in colour, texture and form by manipulating seed sowing, planting medium and levels of irrigation. Yet experimentation with unconventional planting medium is not new, and has been trialled for many years by James Hitchmough and Nigel Dunnett at the University of Sheffield in the UK. Research projects have included: planting through thick gravel mulches to reduce weed infiltration whilst retaining moisture in the soil; combining crushed building material with varying proportions of expanded clay granules and organic matter to create a nutrient-poor planting medium for ‘steppe’ planting designs (done to great

effect by Nigel Dunnett at Beech Gardens at the Barbican in London); and sowing onto a thick layer of sand, irrigating whilst the seed germinated and then limiting maintenance to an annual cut, managing species that may become particularly dominant and weeding as required. Sowing on such a scale, often for planting schemes within the public realm, is the subject of Hitchmough’s book ‘Sowing Beauty’, with schemes ranging from China to the UK. However, establishing large scale public plantings by seed sowing remains largely in the experimental stages in the Middle East. Sowing a pre-determined seed mixture over a wide area has the ability to create a sizeable massing effect and the ‘wow’ factor that comes with closely planted vegetation, whilst reducing the level of irrigation that would otherwise be required to establish and maintain more conventional planting. Having pre-determined the proportion of certain species within the mixture,

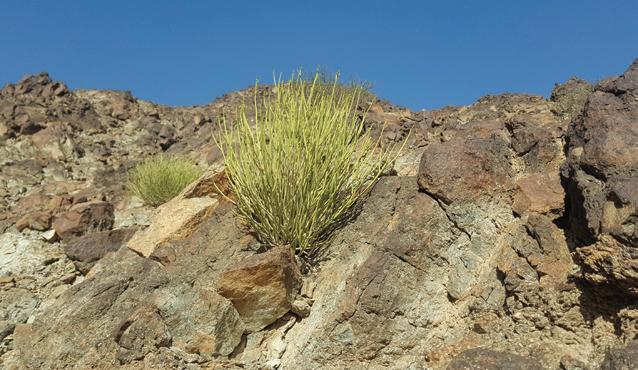

the randomised repetition of species across the sown area creates visual continuity across the whole, as can be found in natural explosions of colour such as those which included swathes of Erucaria hispanica at Jebel Jais in Ras Al Khaimah. The London 2012 Olympic Park, employing such massed seed sowing by Hitchmough and Dunnett, created a platform for this visual spectacle on the world stage. Research undertaken by the University of Sheffield has also shown a positive correlation between flowers planted en masse in a public landscape and the mood of people who view them. In the UAE, where ‘happiness’ is a key indicator used by the Government, perhaps plants should also be included in this equation? However, whilst seasonal wildflowers may create moments of interest at certain points in the year, they do not provide the structure for the year-round continuity of a planting scheme. Shrubs and trees can provide such structure, whilst also adding varying degrees of shadow and texture to interplay with the planting below. Again, the native flora of the UAE offers a variety of forms and shapes that can be employed by landscape designers, from multi-stemmed Acacias with filigree leaves that would not be out of place in a contemporary towngarden, to the more rounded Euphorbia larica, both equally happy growing amongst the rocks and rubble of the nutrient and moisture-poor hills around Shawka, Ras Al Khaimah. These environments provide inspiration for how to incorporate such plants into designed landscapes, and an example of the successful integration of native UAE planting into such schemes can be seen to great effect at Al Faya Lodge, Sharjah.

With the landscape designed by local studio desertINK, native trees and shrubs planted in a predominantly sand planting medium punctuate swathes of hydroseeded, regional planting mixes, with the textures and forms of these plants blending seamlessly into the surrounding desertscape. Whilst irrigation has been required to establish planting of such density, and

subject to constant scrutiny from passers-by, the level needed in the long-run is likely to be significantly less than that for planting schemes more heavily focused on ‘green’ planting, often including tropical plants in their design as can more customarily be found in the UAE. The planting at Al Faya Lodge works so well primarily because it encapsulates its location: surrounded by the Hajar mountains and the desert, it would arguably seem incongruous to have a highly irrigated, lush landscape within such a setting. The planting of the desert, within the desert, speaks of the place it is in with a seamless transition between the two. However, the translation of such native planting into a highly-urbanised environment may prove to be more difficult – whilst the desert and mountains surrounding Al Faya Lodge works in favour of the native plant palette, the highly urbanised, cosmopolitan cities of the region arguably require planting that reflects the gradation of rural to urban, and the expectations that this brings. Hitchmough, in his work researching plant suitability for the urban environment, includes plants

from varied regions of the world but which originate in similar climatic, nutrient and moisture stress conditions. Taking this to an environment such as the UAE, the gradation of planting from the desert to the urban could be managed by including those within the plant palette from other desert regions around the world. The more unusual, ornamental aesthetic of such plants, transitioning into the more urbanised areas, would provide a clear distinction between the desert and the city whilst also having similar irrigation requirements to those native to the region. The result could be a more highly ornamental plant palette than that limited to UAE natives, but one which also corresponds appropriately to its environment. Whether such bold moves are adopted to any great degree remains to be seen, but in an age of sustainability, depletion of groundwater supplies and the power required to desalinate water, it is arguably time to bid farewell to petunias stretching for miles along the highway and embrace more environmentally appropriate and sustainable planting.