Quatervois

EDITORS-IN-CHIEF

TVISHA GUPTA

ANNIKA LEE

LEAD SELECTIONS EDITORS

SOPHIA MA (ART)

ANVITHA MATTAPALLI (WRITING)

PRODUCTION MANAGER

MELODY CUI

PR EXECUTIVE

SONIA VERMA

SECRETARY/TREASURER

ALYSSA YANG

KAAVYA AHUJA, PALAKDEEP BASSAN, MIKAYLAH DU, MICHELLE

HUANG, ALETHEIA JU, TANVI KANDERI, ASHLEY KWONG, BERNICE

KWONG, SAARIKA NORI, KATIE

WANG, SELINA WANG, DANA YANG (EDITOR), JESSICA ZHOU

MIKAYLAH DU, JILLIAN JU, CARINA

January is the month of new beginnings, of yearly resolutions, of bright-eyed wonder. Although the sun rises and sets like any other day, as the clock strikes midnight and we nd ourselves in a new year, we cannot help but hope for good things in our futures: boba with friends, celebrations with family, and achieving our goals.

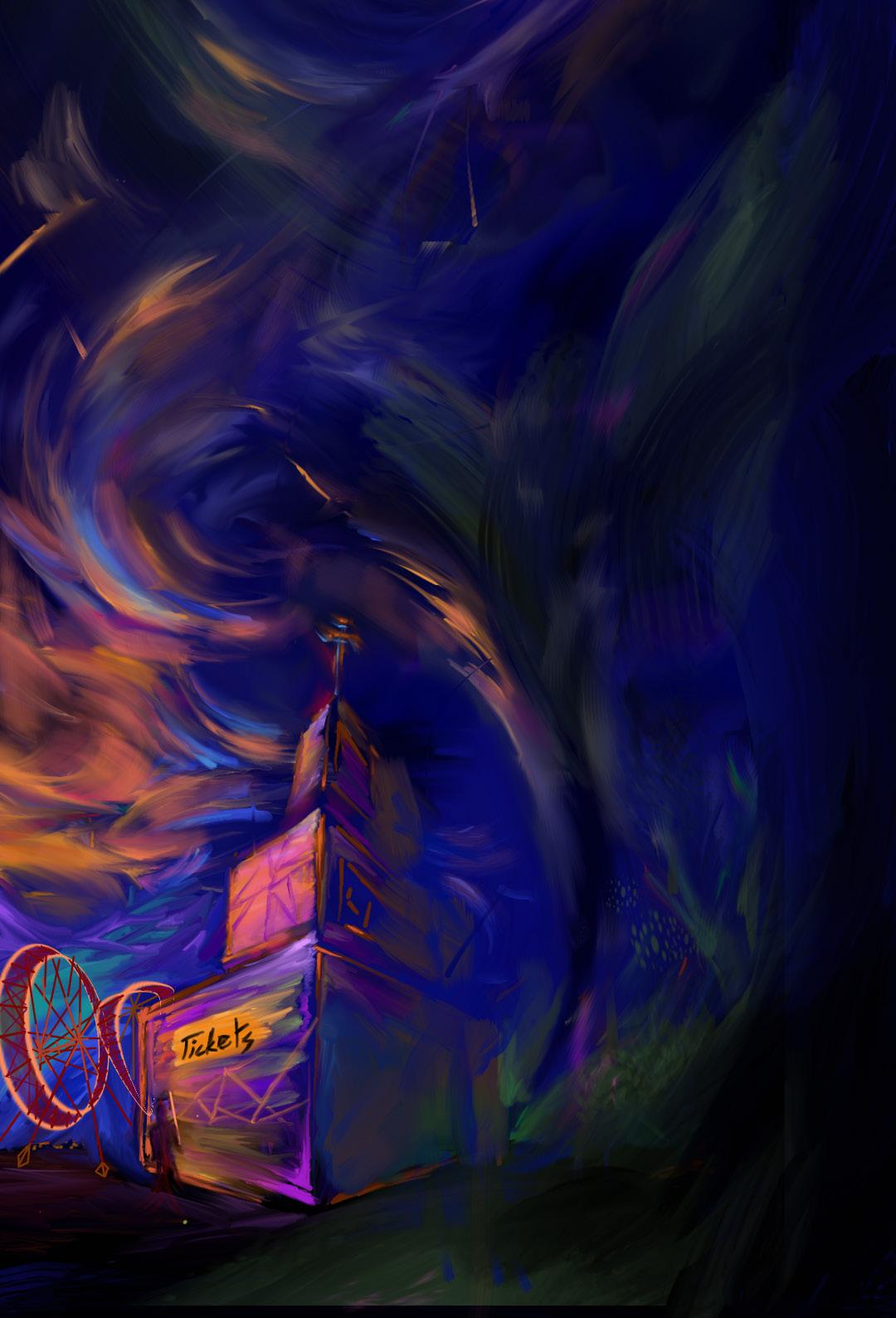

e road ahead is unclear. None of us know what the future will bring, but all of us stand at crucial turning points in our lives. For seniors, our paths are unclear, and we teeter on the edge of the hazy unknown. We will make one of the most important choices of our lives this year. Juniors bite their nails as they begin to turn their attention to the monster of college applications, a thousand tiny decisions in front of them. Sophomores, settling into the groove of their second year, face di erent but no less challenging choices. Which classes will they take next year? Will they branch out to di erent clubs? And freshmen, entering high school with wondrous eyes, have a myriad of pathways before them. e next few years of their lives will be spent here, trying new things and meeting new people. Regardless of our grade level, however, the new year brings with it new decisions to make. Our choices de ne us. ey shape our lives. Perhaps if we chose this, we would be happier. Or perhaps if we chose that, our lives would be lled with sadness. But choices are just that—choices, neither inherently good nor bad. In Volume 03: Quatervois, we reject a harsh separation between light and dark. We visit clown conventions and enter melancholy subway stations. We stroll on ocean cli sides and peek into dance studios. But no matter where we go, all of us stand at a crossroads. And regardless of how di cult our decisions are, we move forward. Grasping both joy and sorrow in hand, we welcome the new year and everything that it entails.

KE, GILJOON LEE, JANICE LIN (EDITOR), SUHANA MAHABAL, ANIKA

MATHUR, RUDRIKA RANDAD, AASHI

VENKAT (EDITOR), ALICIA XU, JUSTIN YAUNG

(n.) a crossroad, critical decision, or turning point in one’s life

by Dana Yang

by Palakdeep Bassan

by Aashi Venkatby Justin Yaung

by Jillian Ju

by Bernice Kwong CHUSEOKS by Giljoon Lee THE BATH by Selina Wang

by Melody Cui

by Saarika Nori

by Anvitha Mattapalli

Suhana Mahabal

by Tanvi Kanderi

by Aletheia Ju

by Kaavya Ahuja

by Rudrika Randad

by Mikaylah Du

by Alyssa Yang

S I L E N C E

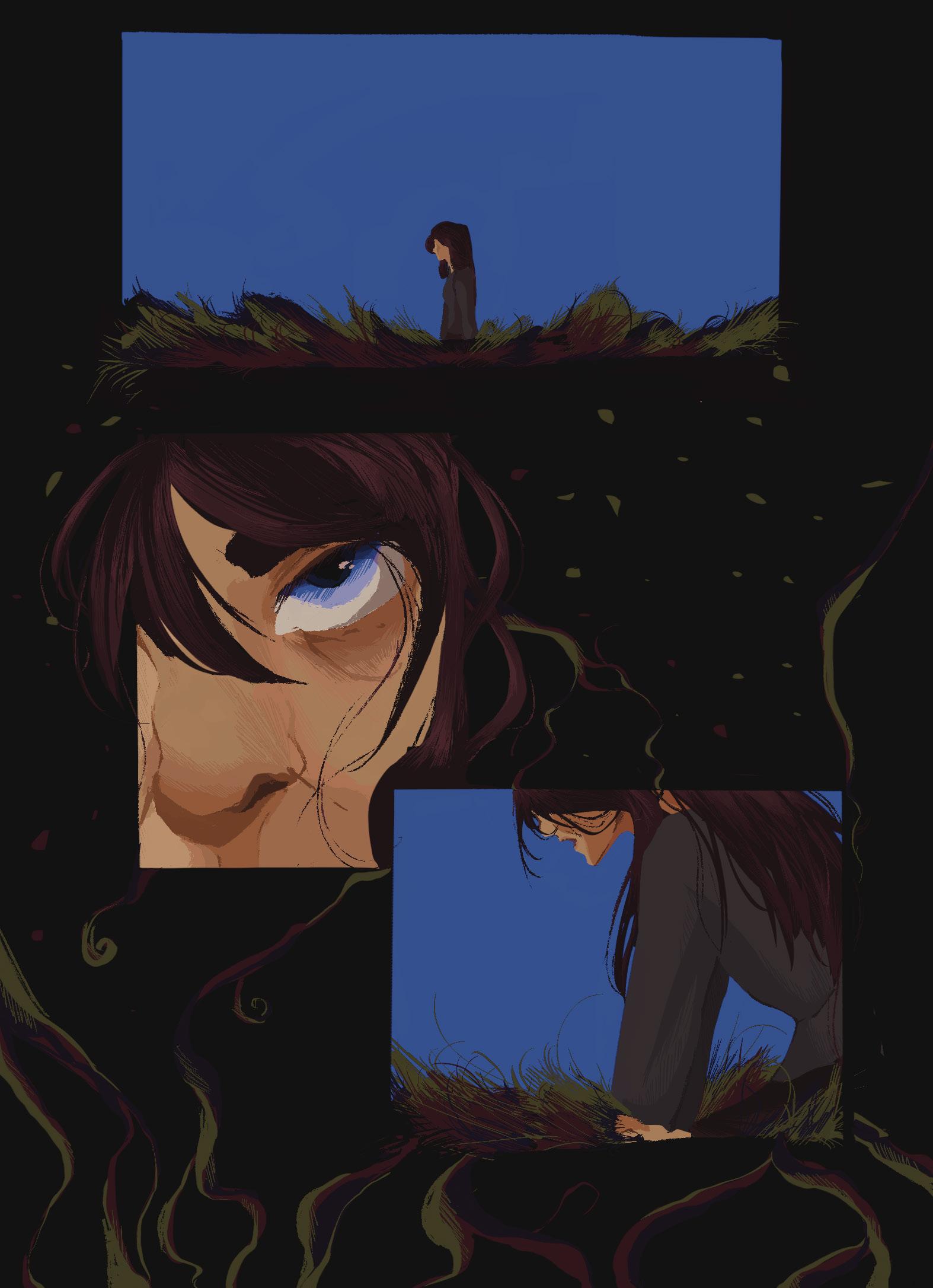

When I was younger, I dreamed of being a ballerina. Seeing them twirling in their satin skirts, their tights molding perfectly around their lean muscles, I immediately knew that was my destiny. So I practiced, morning to evening, around the clock, nailing every pirouette and refusing to leave if I didn’t, starving myself to embody their perfect body, giving up my childhood, my life, to emulate the dancers I saw through the window that day.

Now, staring into the studio with tears ooding my eyes, I don’t remember why I ever stopped. Students my age are now the ones to look up at in awe, with their e ortlessly awless jetés and graceful arabesques. And from where I stand outside, textbook in my arms, with my mind and heart focused on polar opposites, I can’t help but wonder what I could’ve been.

Look down, keep your head down, look not at the mirror but at the words on the textbook instead. Seeing them twirl as squiggly black lines, memorizing every word on every page. Eliminate everything, absolutely everything else. Forget ballet, forget everything other than the words on the page. Only then will you get into the Ivy League; only then will you succeed.

Dropping a passion for socially-deemed success, a binary decision where I simply couldn’t win. Leaving ballet for a major I never really wanted to do: why? For what?

e promises of success, money and an enviable future. Yet every single one of those was now a shattered facade, a lie simply unattainable by the restraints of my ability to do well in something I had no actual interest in pursuing.

Hesitantly, I turn to look at the girl in the mirror. And for the rst time in so long, she’s smiling back at me.

As the dancer in the front turned and met my eye, their golden ecks igniting a re within my once bottomless black holes, realization struck. My textbook drops to the oor — Calculus simply wasn’t for me anymore, if it ever was — and I step foot back into the studio for the rst time in years. Strawberry-scented perfume joins the stale air, wa ing its way into my nose and taking me back in time. Each crevice in the wooden oor feels like an old friend, greeting me a er all this time we passed in silence. Hesitantly, I turn to look at the girl in the mirror. And for the rst time in so long, she’s smiling back at me.

More prepared than ever before, desperately longing to stretch my restless legs and become airborne once again, I set myself in rst position and braced myself to dance the number alongside the dancers.

But now, now, I’m nothing. I worked my whole life, drained all the passion from my blood until it ran dry, every last drop, only to be rejected from every school I applied to.

And yet again, though for another reason, I’m starved.

What if I had stuck with ballet, continued it despite the pleas of my parents, begging me to do otherwise? Would I have achieved the childhood dream — would I have gotten into Juilliard?

Longingly staring at the beauties through the window, I nally stop and consider what success really means.

eir hands on my waist, their golden ecks meeting mine, it all came back more naturally than riding a bike or even walking. And as I was thrown into the air for the rst time in forever, adrenaline pumping through my veins and heart uttering in anticipation, that’s when it hit me: success was not getting into an Ivy League or being the CEO of my very own technology company.

To me, success was my dance. So I never needed to pursue success, I never even needed to try, because I had it. From the very rst day I peered into the dance studio to see the ballerinas who loved to dance, to every day a er.

“Hurry up and nish your breakfast. I’ll be waiting in the car,” I said to Ollie as I walked through the kitchen. Grabbing my keys o the peg, I walked into the garage. Soon enough, Ollie joined me in my Camry.

As he entered, he turned to me and asked, “Ell, why is Dad so sad?” I nearly stomped on the gas, catching myself at the last second. I coughed into the nook of my arm to hide my surprise.

“Huh? What do you mean?” I made a right onto Main St., stopping in front of the light.

“I saw him crying last night. People only cry when they’re sad, so why is Dad sad?”

Oh. Unfortunately, I knew what Oliver was talking about. I had seen it too—I just didn’t realize Ollie had as well. I had woken up from some in nitesimal sound, and walked into the living room to see Dad clutching a picture of my mother in his le hand and a bottle of beer in his right, sobbing quietly into his drink. I just hoped Ollie didn’t put two and two together and associate the drink with the sadness.

“You know how Dad’s been sick for a while? Well, he was getting better, but he hasn’t been doing as well recently. He’s trying though—really, really hard.”

A er that, he seemed satis ed. I steered the conversation away.

“So, Ollie, what are you guys doing for the last day of camp?”

“ ey said it was going to be a surprise!” And with that, I let him out of the car, wished him a good day, and drove home.

A er uselessly messing around on my phone for an hour or so, the phone rang.

“Gab? What’s up?”

“Yo man, it’s summer! We’re going to college in like a week! e hell are you doing sitting around? Open the door already, Elliot.”

I hung up on him, opening the door to see him bouncing on his toes, waiting for me.

“C’mon, we’re going to the movies to get you some time in the sun! You need that vitamin C!”

“You do know movies are indoors, right? And it’s Vitamin

D.” Gabriel was my best friend, and

he had more energy than anyone else I knew. I trusted him with my life, and he understood me about as well as you can.

“Gab, can we talk about something?” As I got serious, so did he, sitting down next to me and assuming a more suitable expression. “I think I’m going to take my break year.”

Gab’s face went from confused to bewildered to, eventually, angry. “Why? You could’ve told me before I already said I wasn’t going to. I would’ve stayed with you. I thought we were going to UCB together.”

I sighed. “I don’t like it either, man. Look, Gab. Dad’s getting worse again. Ollie is, I think, starting to catch on. I need to be here for the fam.”

“Elliot... I’m sorry, dude. I understand, though. You should talk to your father. Work something out. You can’t stay in this dump forever, you know.”

“I’m just going to lie to him—tell him I want to stay because I was really stressed from high school and needed a break. I don’t want to make him feel guilty.”

He stared at me. “Absolutely not, Ell, you have to tell him. Do you understand? You feel responsible for your brother and your father, and that’s completely reasonable. However, he is your father. is means that he has responsibility as well; ten times more responsibility than you. You have to talk to him.”

“Maybe you’re right. I’m just unsure. I don’t know how to even talk to him about that.”

“Look, Elliot. You know your dad better than I do, but I’ve interacted with him, and if you get to him while he’s sober, he will absolutely understand. If you want, I can help you gure out how to talk to him.”

“ anks, Gab. I really appreciate it.”

I turned to Gabriel. “Alright, we should have some time until my dad gets back. Let’s do this?”

Not long later, we heard my dad pull up, and Gabriel hurriedly le through the back.

I opened the door for him, steeling myself for the talk. Gabriel’s parting words were still running through my brain: “It’s not a speech, Elliot, it’s a discussion.”

Dad walked through the door, dropping o some groceries in the kitchen. A er we were done restocking the fridge and cabinets, I turned to him.

“Dad, can we talk in the living room?” I grabbed myself a cup of water, taking a sip on the couch and motioning him over.

“So... I’m not really sure how to start this.” Swallowing,

I began. “Dad, I’m going to take my break year.”

“Oh, is that all?” He chuckled. “And here I thought something bad happened. Where are you going to go next year?”

“Wait, wait. Let me nish. Look, I’m taking my break year because... well, because I don’t think you can take care of Ollie in your current state.” At this, he opened his mouth, but I cut him o immediately. “No, no, let me continue.” A er he nodded, I went on. “He’s getting older, and he’s not as oblivious anymore. He’s picking up on things, and I’m his older brother, you know? And I’m still not happy you didn’t show up when I wanted you there. I can’t leave it up to chance that you won’t just abandon him, too, when he needs you.”

Dad hadn’t showed up for my valedictorian speech, leaving me with just my aunt Jennifer and Ollie in the crowd. Later, we found Dad in his car, passed out drunk, and I spent graduation day cleaning up puke. at day, I despised him. Today, I didn’t know how to feel.

I meant what I had said.

“Elliot. How old were you when your mom passed? Eight? I’m trying here, Elliot. Give me some time. You don’t need to stay home. Go to Berkeley with Gabriel.”

is conversation wasn’t going anywhere. “Let me make this choice, okay? Maybe I don’t trust you to take care of him. Maybe I’m worried you’re only going to get worse. Maybe I want Ollie to have someone here for him, because I know what it feels like to be alone.”

His shoulders slumped a little. “Yeah. Yeah. Maybe you’re right. Look, I’ve been thinking. I have some plans, if you’re interested.”

“Let’s hear it,” I said, hopeful despite myself.

He sighed. “I hear you, but Elliot, I know you don’t actually want to take this break year. You’re not taking it.”

I hardened my tone. “Dad. I’m going to stay. is is my choice, okay? I’m 18, Dad. I’m an adult. Let me make some hard choices too. I need to be here for him, and I think I can help you get better as well. I need to do this.” I took a long swig of water, swishing it around my mouth to try to remove the a ertaste I was getting.

“Elliot, I know I haven’t been there for you. And I’m really sorry for not being the father you wanted. I just want to tell you that even without me or your mother playing signi cant portions in your life, you’ve become an amazing young man, and I’m proud of you.”

As emotionally charged as I was, that resonated with me, and I had to blink back tears. Even so, that wasn’t what I wanted from him. I wanted him to own up to being a bad father to me, and I wanted him to let me shoulder my responsibility and take care of Ollie.

“What, are you saying that you can be an absentee father and Ollie will turn out good anyways? What kind of garbage excuse is that? Are you a father or not?”

He visibly tensed. I regretted the words instantly, but

“Let’s hear it,” I said, hopeful despite myself.

A er letting out an exhale, he began. “It’s been, what. A decade? More? Too long for me to be living like this. I think I’m.. going to go into rehab. I have to cut this o now. I’m sorry I wasn’t around for you, but maybe I can x myself so that I can be here for Ollie.”

I was at a loss for words. “I... Are you really going to do that? Who’s going to take care of Ollie while you’re gone? Isn’t this just more reason I should stay?”

His eyes lit up a little. “Do you remember your aunt Jennifer? Well, I guess you know her as Aunt Jen. She went back to college a couple years ago, remember? Well, she’s done now, and I asked her if she would take care of Ollie. And obviously, I’ll still be around over Facetime or whatnot. Now go dial up Gabriel and tell him you’re going to Berkeley this year.”

“Okay, Dad. We’re picking Ollie up from camp tonight, right? We’re going to tell him?”

He nodded at me, and I le the room, lled with new hope.

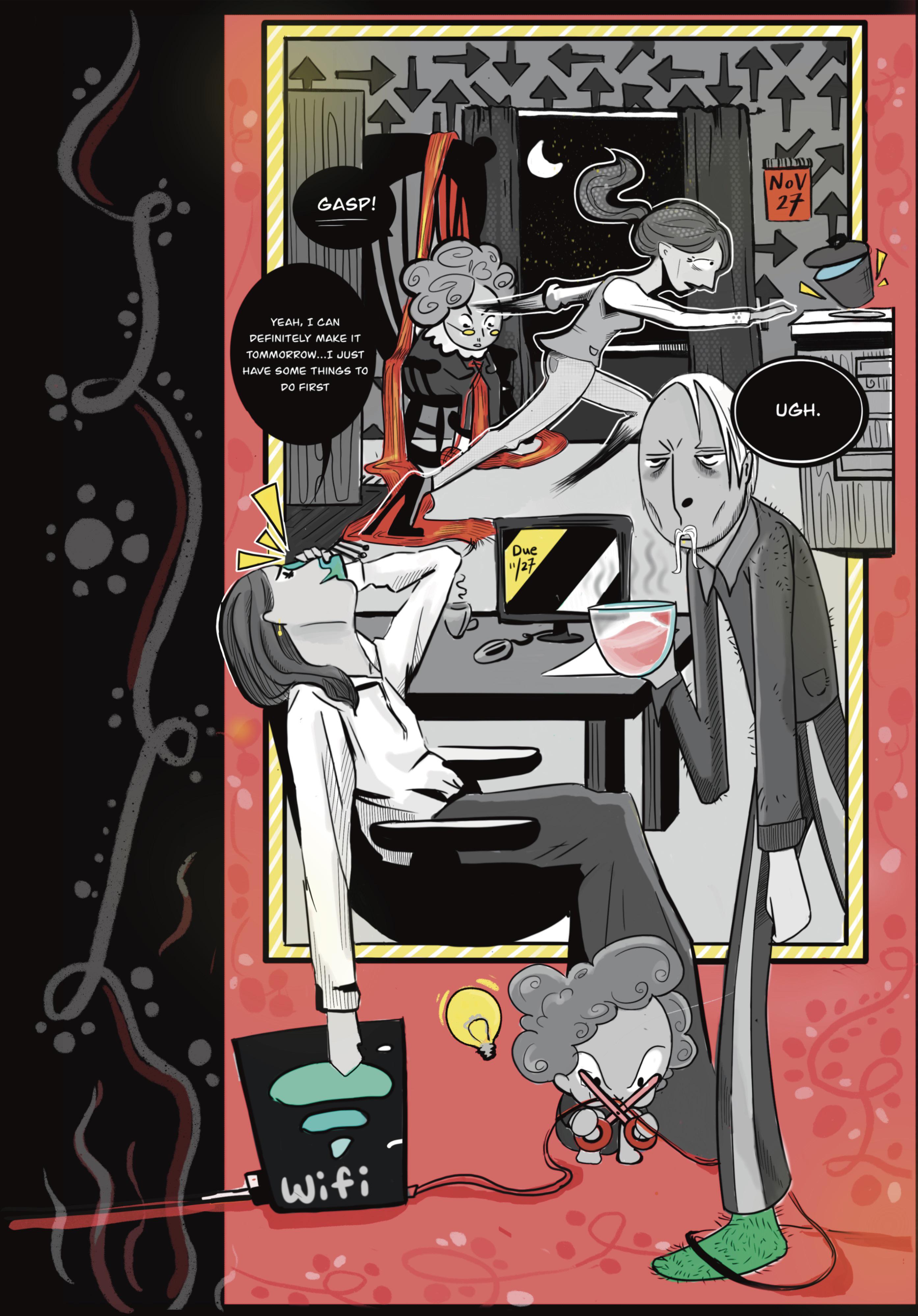

enny took me to a clown convention. I didn’t want to go to a clown convention. I wanted to park near a McDonald’s and down too many watery co ees and marinate in my own anxiety as I waited for DataGenerics to call me back, but you can’t always get what you want.

“It’ll be fun!” she told me. “You can’t just keep moping all day. You need some clown in your system to balance it all out! You know?”

I didn’t. And I still don’t.

But Denny, she has her life together. Her job at one of those background check agencies sounds boring, except she’s lled with career stories that make it sound like the most eventful thing ever. She knows what she wants to the point where she can show up at a clown convention and feel absolutely no self-consciousness. Right now, she’s listening attentively to someone dissecting the anatomy of a balloon animal.

Denny, she has her life together. Me, I have a rocky history of freelance jobs, a useless degree, and a few dreams rotting in my studio apartment. e dreams looked pretty promising—accounting seemed solid, baking would be fun, and at one point I even seriously considered being a career clown. But that fell through.

I’m stuck between acknowledging her point and allowing myself to feel horri ed at the idea of spending hours at a clown convention.

She shakes her head. “Besides, the comedy panel is about to start, and we both know that you de nitely need to learn how to take a joke.”

I can only attempt to reason as she pulls me in the direction of the crowd.

wait is the comedy panel starting…

“I know you mean well—”

hey I heard that Marla Mars is going to be here…

“—but you can’t just tell me not to worry—”

I’m stuck between acknowledging her point and allowing myself to feel horri ed at the idea of spending hours at a clown convention.

“Data analyst” sounds mind-numbing, but what alternative do I have? Continuing to take odd jobs might be enough to sustain the life I have right now, but it’s nothing in the long run. Taking the o er would give me stability—at what cost?

Am I willing to give up the excitement of a vague future?

Am I willing to settle for a routine?

Am I willing to continue living like this—

“Are you willing to actually pay attention?” Denny says, annoyed. “I know you’re caught up in your own decisions, but you just need to unwind! Take your mind o of them! You stayed up all night thinking, right? ese few hours won’t make a di erence.”

uh, what does true crime have to do with clowns?

“—I need to make this choice, Denny—”

I dunno, just heard that she might be around…

“—the rest of my life literally depends on it.”

Finally, she pauses, unwise considering the sheer volume of people who are suddenly pushing past us. But maybe she nally has something to say.

Turning around, she wears the exasperated face of a mother lecturing a child. “Look—” Which is as far as she gets before someone slaps me in the face.

“AAAAAAAH—” I scream re exively, stumbling into a clown. “WHO—”

Denny frowns and looks around, spotting the perpetrator battling a sea of clowns abound; it’s a guy in a gray suit, shoving through the confused crowd. He’s remarkable at making progress, just as he’s remarkable at turning heads. A few others adopt the same confused expression as me, not that there’s much to be debated. e culprit is the only one dressed in depressing gray among a sea of color.

“Are you okay?” Denny asks as we slip into a less crowded area. “ at looked like it hurt.”

“Yeah.” As if everything else isn’t already a slap in the face.

“But you’re okay now, right?” She’s glancing at the

passing convention-goers like she’s more eager to rejoin them than remain here with me. “Nothing bad?”

“Yeah,” I repeat sarcastically. “First I get my sixth consecutive sleepless night, then I spend all morning agonizing about my job and my future, then I get dragged to a clown convention, then I get slapped in the face by some guy whose fashion sense is literally ‘concrete,’ none of which helps the fact that I need to make this choice before I run out of alternatives—I wouldn’t call that bad.”

“You wear all gray too,” she murmurs.

“ at’s not the point,” I say, wishing I was anywhere but a clown convention. “ e point is that I wanted to ask you for your advice about a choice that’s too big to make myself, because I trust you. And you’re my only friend.”

Denny gives me a sad smile. “You know, I can’t tell you what kinds of choices to make. ere are sides to each, like you said- I can’t tell you that there’s some right decision. at wouldn’t be true.”

“Sure, but I’d appreciate some kind of input, some kind of opinion besides telling me to distract myself. And that slap really didn’t make me feel any better. It’s career, Denny, you’re lucky to have something you like-”

“You’re making me worry about my own job.” She pulls out her phone and starts scrolling. “Oh, look, an old applicant. A new request. Some notes I need to update. An urgent pro le. Is this what you want? Do you want? Do you want to spend a day out like this when you’re already stressed enough?”

I open my mouth to reply, but before I can, she spots something over my shoulder. “Wait. Is that…”

I sigh preemptively.

“TRUE CRIME PODCAST HOST MARLA MARS?”

“I don’t even know who that is,” I try to say, but before I can she’s already handed me all of the stu in her hands and dashed into the crowd.

I need to make this choice. I need to decide sooner or later, otherwise my future (or lack of one) will be my fault completely. I can’t just naively chase my dreams, nor can I dismiss them. Pay. Passion. One of them. Not both. But I need both. I need to make this choice. I need to—

“How’d it go?” I ask Denny as she comes back, beaming.

“I’m pretty sure it wasn’t her,” she says, taking her coat and phone back. “But she’s also a huge fan of Marla Mars, so we just had a nice conversation before she said she had to check on her dog! Which is weird, because no dogs are allowed here, but… she was nice!”

Seeing her cheerfulness, I’m a little wary of bringing up the gloom again, but I can’t help it. What else is there to think about? “Denny, please, I need you to just tell me your opinion. Just tell me this once and I’ll shut up, okay? Do I take the job or—”

My phone is ringing.

Oh.

“Who’s calling?” she says, leaning over to look, before her face turns pale. “Oh.”

“Do you... do you want some privacy?”

I’m about to say no, but she gives me a nervous thumbsup and runs o anyway. “Hello?”

“Yes?” I say, my heart pounding.

“Hi, I’m calling from DataGenerics to update you on the status of the position you applied for.”

“Oh.” As if that wasn’t the only thing I’d been thinking about for the past week. “ at.”

“Yes, it seems that you were interested in the data analyst entry position, correct?”

Here’s my chance. ere’s no going back.

So do I take the job or not?

On one hand, the pay. On the other, the passion. Pay. Passion. Pay. Passion. Pay—Denny’s phone is unlocked.

It’s open to an application pro le, minimized in the upper right. Taking up most of the screen are her notes on the person:

– Lazy

– Disruptive at large gatherings (e.g. clown conventions)

– Described by previous employers as “annoying” and “pessimistic”

And the big REPORT button at the bottom.

It’s the guy who slapped me. ere’s no name or picture, but the description is dead on. I could. Whatever job he’s applying for, I could get him dismissed right now.

It’d be immoral.

It’d be ne.

He had it coming.

So I press the button, and under “Concerns,” I put “bad employment history” and “horrible fashion sense.”

REPORT DELIVERED

I close the app.

Now just to think.

Pay.

Passion.

Pay.

I’ve made up my mind.

“Actually,” I start, but my voice is a dry rasp.

Come on, tell him that you want to—

“Unfortunately,” he continues, “you’ve been disquali ed from the position.” ...what?

“Our background checker has found some issues with your application, and as this is a highly sought a er job, we will not be able to hire you at this stage. I’m calling to let you know that you’re no longer being considered.”

…no.

“ ere has to be some kind of mistake.” is can’t—

I’ve been thinking about this for so long—

How could they—

“If there is an error,” he says, “it’s that they put ‘horrible fashion sense’ under the list of complaints.”

From the tables of the breakfast bar at Seoul’s Shilla, I can see your rundown one-room apartment complex through the oor-to-ceiling windows. e building’s exterior is made of gray faux-stone bricks, its windows tinted with grime, clothes racks with partially dried clothing on its cramped balconies. You moved into the apartment a year ago from the apartment he and Grandma shared with you.

I’m wearing the pop art-print sweater you gave me as a hand-me-down. You said it was out of style; you had bought it a month ago. When he saw me wearing it a er the ight, waiting for him to pick me up, his smile was contaminated with a grimace. e expression was brief; I think he wanted not to sour the moment. He only sees me once a year, a er all.

A waitress dressed in a sharp black suit, a handkerchief over the arm, stops by the table. Eying the cup stained with the remains of orange juice and the empty plates with the residue of cranberry jam and bread crumbs, she asks with a plastic smile, “Are you nished with these, sir?”

I nod; she takes them away, stacked.

Reaching for the copy of e Giver that you got me on the edge of the table, I stare blankly at the cover, my thoughts wandering.

It was a year or two ago that you got me the book, during the day before the annual Chuseok family gathering. My quasi-annual visiting week. When you opened the front door and saw me there, you greeted me with a bright smile and a hug. Your face was caked with makeup—le overs from your unplanned outing with friends—and when you hugged me, the smells of your perfume, hair products, and cigarette smoke mixed into a chemical haze. Pulling back from the embrace, you said, “I can’t believe it’s been so long, I’ve missed you! e baby photos of you on my phone reminded me of the memories from when you were an adorable little child. Look at you now, you’re an American man!”

might...you know.” His voice trailed o

“I know, I know. Okay, yeah,” was your disembodied reply.

A moment of awkward quiet. en, as if wanting to forget about the conversation, he said, “Come out for family dinner in thirty minutes or so. I’ll call you.”

“Got it.”

A er the dinner was when you gave me the book. Seated on the living room couch, stomachs warm and lled with seolleongtang, you pulled it out and said with a cigarette breath, “I know your birthday is in a week, but you’ll be in America by then. So um, I got you this. I know you like books so I thought you might enjoy it. Don’t worry, it’s in English. I’ve only read the Korean translation of it, but it’s my favorite book.”

Taking the book in both hands, I thanked you.

You then rose and declared that you were going to spend the night at a friend’s. As you were putting on your shoes at the door, he warned, “Be here on time tomorrow.”

Despite you being eleven years older, that was the rst time you felt like an older sister.

“I will, don’t worry,” you assured him. en, you turned to me and said, “To be honest with you, e Giver’s the only book I’ve nished.”

I had read e Giver a few years back. I didn’t have the heart to tell you so.

Lying on the portable mattress of the living room that night, I remember thinking that despite you being eleven years older, that was the rst time you felt like an older sister. Someone who I had an emotional attachment to.

I forgot what I said in return. Probably some white lie about how much I’d missed you, my cousin-cum-older sister gure.

Saying you had to wash o the makeup, you rushed over into the bathroom and turned the fan on. You came out a few minutes later, face unwashed, and headed straight for your room. When I used it a erwards, the air inside was thick with cigarette fumes and a su ocating amount of Febreeze. Coming out of the bathroom, I asked him about it and his face contorted into one of exasperation.

“Haven’t I told you to not smoke in the house?” He shouted wearily through the door into your room. “ e upstairs neighbor complained about it twice already and you know Grandma’s lungs are weak. You don’t know what

I reminisce, albeit with hazy memories, sitting outside your locked room during Chuseok, pouting. At age seven, I was the nagging kid that just wouldn’t leave you alone. Taking inspiration from the Detective Conan episodes I had seen, I took a rogue paperclip and straightened it into a wobbly line in an attempt to turn it into a lockpick. I forced it into the keyhole, prodding around to no avail. I took it out, jammed it upwards, and with my little hands, attempted to turn it, the thin metal digging into my ngertips and palm. Eventually, he noticed me and told you to open the door. You complied with a sigh.

Cluelessly, I barged in with a triumphant yell, red marks on my ngertips, and jumped on the bed. You were videocalling with friends, phone propped up against a portable pedestal mirror. Vision xed to the screen, laughing at inside jokes incomprehensible to me. Jumping up and down on the mattress as if it were a trampoline, I made futile attempts to get your attention periodically: “Who’s the person on the phone?” and “Do you wanna hear about what I learned in Science class at school?” and “Why did the chicken not cross the road? ‘Cause it chickened out!” You responded with distracted “okay”s and smiles too wide to be real.

e next day, before the Chuseok ceremonies and dinner, you came in through the door, as promised. You were the same as yesterday: heavy makeup, chemical haze. You greeted the family with hugs and exaggerated smiles.

e next day, right before the Chuseok ceremony took place, he texted you frantically, asking where you were. “Sorry, some things came up. I’ll be there in a bit, start without me!” you texted back. His face ashed in anger, then into one of forced calm with hints of annoyed wrinkles.

“Okay, guys, let’s start,” he called the family.

e proceedings went as normal. We set the table up elaborately; soups, jeons, pears, rice cakes, and cheongju sprawled out on faux-wood. e family sat around it on red velvet cushions; Grandma said the familiar request of blessings to ancestors, to Grandpa. We bowed. We ate dinner: duck roast shared on a stained wooden dining table, its chairs creaking, legs uneven.

“So, how are things going with work?” he asked you with a mouthful of duck.

“Not bad,” you replied. “ e cafe’s not exactly a very exciting job.”

“Well, it’s part-time too, right?”

“Yeah.”

“Any plans for a er the cafe?”

“Not really. I dunno what I’m doing now—how can I know about the future?”

“Does anyone know where the kid is?” he asked the family about you.

“Not particularly,” I said.

“Is she at some karaoke bar, like last time?” I shrugged.

“I swear, if she does that again, I will—” Grandma put a hand on his shoulder and his voice trailed o .

“I’m sure she has a good reason for it,” she assured. “Trust her a little.” He pursed his lips.

“I read that baristas are hot these days,” he said. “Hot in the, you know, trendy way.”

“Don’t you need a license for that?”

“Maybe. But you should try it.”

“Eh. We’ll see.”

“Well what else are you going to do then?” he questioned.

It only took a few moments of silence for him to regain his irritation. “She’s twenty-six, not a high schooler.”

“She’s still guring things out. And besides, she could join the family business in a few years if it doesn’t work out,” Grandma said.

“What would we even hire her for? She’s been bouncing around part-time jobs. She’s got to start sticking with things for longer than a few weeks.”

“I’ve got no idea. I’ll gure something out,” you replied.

“You can’t keep on going around borrowing money from me that you’ll never repay then get mad when I confront you about it and couch surf for a week. At least just try something.”

“I am.”

“You aren’t, and you know it.”

Over the sounds of the two bickering, I texted you under the table. “grandma and him are arguing about you they’re getting pretty worked up.” You texted back in seconds. “thats kinda funny tbh. what are they saying?”

“the usual. he just said that you can’t stick with anything for longer than like four weeks.” “oh.”

“Okay, okay, I get it.” You stood up from the chair and let out a frustrated sigh, muttering, “God, you’re always just mad at me.”

You picked up your phone and walked out. e sound of the metal apartment door was heavy, your footsteps echoing in the hallway outside, the elevator’s chime and its door closing.

“What are you looking at under there?” Grandma asked. “Oh nothing,” I said, turning the phone o and tucking it in my pocket. His phone vibrated, an alert. Mine did too. We had identical noti cations on our home screens: you had le the family group chat.

A er a few weeks of couch sur ng friends’ houses, you found a dingy little apartment in Seoul, one next to Shilla. In the breakfast bar, I put down e Giver and reach for my phone, scroll till I nd your contact. Eyeing the apartment complex, I call you.

the yellow orb glows with its radiancy, and I want it I want the thrills of ignorance and of indi erence, the only thought in the world being so trivial there’s none, where the problems of existence are incomparable to the merits, a yellow-tinted lens in place of every single imaginable horror.

And I want it because I want it, and I want it because everyone else seems to have it, and I want it and I want it so bad because if there was a cure to the poison of life, this would be it.

And I see other people with it, their hands fondling it like it’s a toy,

with their smiles and their careless laughter, unaware of how much I want it.

And they act like its a birthright, like they deserved it just because they got lucky, treating it like it’s nothing yet everything just because I don’t have it. I would wrench it out of their hands if I could because I want it more. I need it more. I crave it more.

And if I want it so bad, shouldn’t it be mine?

And if I want it so bad, shouldn’t I deserve it?

And if I want it so bad, why can’t I have it?

Anvitha Mattapalli

when the world burns to ashes, lush hues become obsidian. the owers wilt away from the radiance of the sun, whispering to each other about their hope that’s seeping between their petals while their bees buzz o for shelter in their hives. as the tides wash our souls from the shoreline, mixing them with broken promises and unkept secrets, stardust and honey paint our sky a sickly gold, taunting us for choosing riches over nature, the world breathes its last breath. and through it all, i don’t turn tail and run. i lace my hands in yours, and face the end with you, for you. for i choose you.

Annika Lee

plant this where the seaside blooms the roads diverge where the sunset ends in the meadow pale pink and fresh. call it a seed a wish planted on promise turns into the bridge between branches that bend and lives that converge yet never splinter and sprouts early call it a leaf fragile and delicate for it trembles like seafoam fading but stretches for joy under touch. call it a root anchor it sinking and slipping to the past through homes and memories call it a trunk lled with joy love growing steadily in earth settling on untouched stone call it what it is me.

No one at the station that day was paying any attention to them. e crowded concrete room was lled with too much cigarette smoke and sweat, the heady late June sun already bearing down on the city in the early morning.

e businessmen shi ed uncomfortably in their decadesold suits, their thoughts already enraptured with their next meeting. e few teenagers skipping school anxiously eyed everyone, as if any one of them were a truancy o cer. e college students sat with their headphones in and books in their laps, trying so, so hard to hold onto their romanticized ideas of adulthood.

But their eyes were locked despite the tracks between them. Her eyes couldn’t leave his and his couldn’t leave her lips. To anyone who might have seen them, it would have looked like a scene right out of a movie—the scene where the two leads realized this was love at rst sight—this was what they had been missing out on all their lives.

It felt like fate had had a part to play, intertwining their paths.

e metro rolled in, lling the dank air with a sense of urgency as people crowded on, barely glancing back as they pushed past people, hands ying and heads whirling. But they walked on slowly, slipping through the crowd as if they were made of liquid glass, their minds xated on only one person and only one idea.

“Hi—” he started, and she could already see that he was already absolutely in love. She felt a smile creeping on her face knowing she felt the same as she took in his open demeanor, the crinkle of his eyes as he smiled, the slight curving of his shoulders as though he was unsure of where exactly he t in. His warm laugh that seemed to run through her entire body as they sat together, exchanging stories about everything that itted through their heads because they couldn’t possibly leave behind the conversation and the other person.

“I’m sorry, this is so sudden. But this a ernoon, do you maybe want to come to the park with me? Take a walk or something? You don’t have to—”

UNREQUITED

Jessica Zhou

e idea of loving someone was painfully uncomfortable and scary

but if it would really hurt that much then why did it feel like fate had brought them together for a reason?

you can always say no no one’s forcing you

But maybe this time, just for fun, she’d say “yes.”

And he smiled and said, “See you there,” and she smiled, and wondered if she’d ever actually see him again. She hoped she would.

Sitting up on his apartment roo op, she leaned into his shoulder, feeling his head lay on top of hers, a slight smile curving along his face. As they watched the sunset blaze over the thousands of buildings, eventually slipping below a darkening ocean, she felt herself slipping into unconsciousness.

“What’s your favorite thing?” he asked, pulling himself away to look in her eyes. Her heartbeat sped up like it always did. Two months had done nothing to soothe her feelings around him, no matter how many times she watched him snore in his sleep—in fact, maybe it just made her fall more in love. Even the most simple things about him still entranced her, a er all this time. His cozy laugh that felt like roasting chestnuts over a replace at Christmas. His slightly crooked smile that wasn’t perfect but lingered in every room he had ever walked into. His eyes that melted at everything she did.

“I guess just this. Watching the sunset with you. Anything with you,” she replied, meeting his eyes with a slight smile. When their lips touched, she felt sparks along her arms and legs and throughout her body, tingling with the sensation of his mouth. As she watched him watch her, she noticed how his shoulders seemed straighter and broader, more con dent in his stance and demeanor, a drastic di erence from two months ago. was it because of me?

Arms interlocked in an embrace that felt like it might go on forever, ears listened to each other breathe on that roo op high above a city that never seemed to darken. e millions of people with their own winding life pathways and intersections and crossroads that might cross with each other but never touch, some holed up in their apartments, others out on weekday nights, the lights on in their apartments—the city never fell silent. But up there on that apartment roo op? You could have heard a pindrop.

mind and words.

“I love you too,” he said, and at that moment, they could have sworn that things changed. e air shi ed a little and the energy brightened and suddenly, it felt like fate was hovering over their shoulders and another gate had been opened.

It was them and only them in their little corner of the world.

She knew what was about to happen. It was as clear as day. e moment, the feeling she had been longing for since she was a little girl with a plastic princess tiara on her head, stumbling through the house in her mother’s heels.

She could see it in the nervous bounce in his knees and the twitch in his ngers and the location he hadchosen. Because really, who chose to go on a walk on the beach at sunset, fully dressed in formal wear?

And yet she still felt the thrill rushing through her bones when he got down on one knee. e chill spiraling through her bones at the idea of forever with him—not a prison sentence but an exciting promise. Saying yes meant letting another person in and signing away a part of yourself and your freedom. But wasn’t love about sacri ce and choice? Wasn’t this what she had wanted to do for so long, ever since they locked eyes in that grim subway station?

Forever was a very, very long time. But with him, forever seemed not like a curse, but a sanctuary.

So when she answered and he smiled and took her in his arms and swung her around it felt right and nothing had ever felt more correct this was the way it was meant to be maybe fate did exist.

Fittingly, the day was as balmy as the day they had met.

An end to a story, she thought grimly, gazing down at his placid face. His eyes that had once enraptured her now lay shut, his features as expressionless as a statue. At this point, he was nothing more than a statue.

Forever was a very, very long time. But with him, forever seemed not like a curse, but a sanctuary.

It felt so obvious to her the way that they both felt. e glances across tables, hands clasped together, laughing at just a look that said everything that they meant. Vocalizing it felt like a di erent story entirely.

“I love you,” she said, and almost immediately it seemed like time stopped for a second and the second thoughts started to creep in, weaving their way through her lips and

Beside her, her sister slipped her hand through hers, resting her head on her shoulder. Looking up at the sky, a thousand thoughts raced through the woman’s mind. All of a sudden, it felt as if she was holding up the world, her shoulders shaking under the weight.

Every moment, every touch, every memory raced through her blood as she looked at his cold body. Looking back, every I love you now felt like an omen of death, an ever lingering chill in her blood.

“At least you had all of those years. You wouldn’t want to give them up,” her sister whispered to her.

Maybe I would for you, she thought silently as she looked down on his beautiful face.

at night, sitting up on their apartment roo op, it occurred to her that tonight, the city was silent.

The path winds around the top of the cli . On each side a border of sea campion mingles with clumps of overgrown scarlet nightwort, leaving withering petals strewn over the earth. Sharp, narrow insects have burrowed thousands of minute holes into the earth, almost like frostbitten sponge.

creamy-seeming clouds spiral and break in vanishing galaxies across an azure luminosity;

Beyond the mossy patches of owers, the cli takes a sharp drop into the ocean. As you approach the edge, you peer over to look at the view: black reefs emerge from the froth here and there, lubricated by the surf and crowned by haloes of mist. e sun corrodes the surface of the sea on the far horizon, painting a visage of obscene gra ti onto the water.

glitter crosses the textures of water as if swarms of insects; e a ernoon has yet to make its entrance, so you stand at the edge, waiting—for what? for—

A sharp gust blows in from the ocean, and you watch crows tumble like paper planes in the wind, before returning to the dirt path.

As you walk down the cobbled-together trail, an abstract numbness settles across your body. Have I walked this path before? you wonder, as you leave small dust clouds in your wake. e road is simple and plain, the empirical line of lines, as the shortest path between two points without depth or breadth or any sort of sentimental value and all that remains of the path is a featureless walk like that of a corridor in a madhouse and every single step takes you closer to the end—the end of what? i don’t know. why do you say that? i don’t know. alright. A sharp snap sounds from under your boots; you glance down to nd a blot of vibrant scarlet on the dirt.

scarlet

scarlet

sca

and ruined his drawing,” or “Charlie vomited in the ball bin today”). You would try wandering around the room doing a little shimmy shake, or crossing your eyes and crowing, or putting peanut butter on your nose and trying to lick it o with your tongue. Most of the time, these activities just irritated your mother, and she’d shut you up with, “that’s not amusing, that’s disgusting,” or “stop it, you’re giving me a headache.” But once in a while, you would get a smile, and then all your sorrow would vanish.

On the rare occasion, her eyes would glaze over, and she’d run to the kitchen and prepare a pretty little meal, just for you. It would be so extravagant and arranged, it frightened you. ere would be colored paper napkins, and table setting, and perfectly cut PB&J sandwiches— except the jelly would make a little smiley face on top of the sandwich, and there would be orange juice served in a wine glass right next to your plate, because she’d forget that you were still young and couldn’t handle delicate stemware. But that was irrelevant because for once, she would do something for you.

She would carefully dress up, all sparkling attention and she would look at you, all ears and attention for you

—the end of what? i don’t know. why do you say that? i don’t know. alright.

You knew you had to be appreciative, and you would make a big show for her. “Oh boy, my favorite!” you’d say, then rub your stomach in a caricature of hunger. But then your mother would laugh and it would all be worth it.

As you grew older, it became more and more obvious that your little tricks wouldn’t do anything; if you couldn’t get approval, you would get a reaction and that would be enough. Anything was better than the blank eyes, at voice, and the tired staring-out-the-window. You started with:

“Can I have a cat?”

“No, you cannot have a cat.”

“Why?”

“Cats might carry diseases that would be bad for us.”

A scarlet bathrobe, draped uncaringly on your mother.

An image from years past: her sitting at the dining table, still with the bathrobe on when you returned from school for lunchtime. ere would be a cup of co ee sitting in front of her, long cold, and she would be staring blankly out the window and smoking, ashes falling into the cup. God knows how much ash and crap you ate because of her.

It was an unspoken rule: there would be no lunch ready for you, you would have to make it yourself, and she would call out directions in a taciturn manner. “ e milk’s in the fridge. To the le . No, the le . Don’t you know your le ?” She sounded so tired. Perhaps she was tired of you.

More than anything, you had wanted to make her laugh—to make her happy. You would tell her about funny things that happened at school (“William got a nosebleed

“But you don’t care.”

A sigh, a pu of smoke. “Other people care.”

“Can’t I have a dog, then?”

“No. No dogs either. Can’t you nd something to do in your room?”

“Can I have a parrot?”

“No. Now stop it.” She wouldn’t really be listening— these were all at responses. “Can I have nothing?”

“No.”

“Oh good! I can’t have nothing!” You would crow. “So I get to have something. What do I get to have?”

“You know, sometimes you are a pain in the ass.”

“Can I have a baby sister?”

“No!”

“A baby brother then? Please?”

“No means no! Didn’t you hear me? I said no!”

“Why not?”

at was the tipping point, that would do it.

She might start crying and throw her co ee cup and hit the kitchen counter, or she’d run out the door and collapse into a sobbing mess on the front porch, or she’d slap you and then cry and hug you, or it might be a combination of it all. Or it could just be the crying—she would shake all over and gasp for breath, choking and sobbing.

You could hardly tell what to say at that point: you were happy when she was unhappy and when she was at peace, you were unhappy. You would pat her, as if she were a dog, saying, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry.”

But you gloated in those moments, congratulating and patting yourself on the back because you had managed to create such a visceral reaction.

Ironic, then, how any semblance of viscerality seems to have ed your system now.

Hours had now passed, walking endlessly on the path. e scarlet splotch of a once-bug-now-dead lies far behind you now, and all you can see is continuous sea. i feel myself not a concrete thing, not even a glori ed jelly sh marooned on a rock; e so , early-a ernoon glow of the ocean had dissipated the billowy clouds and morphed into the excruciating heat of the late a ernoon. You scan the

horizon, looking for something but there is nothing: the sea is melted glass and the sky is bleached cloth unbroken except for the hole seared by the sun. Everything is so empty.

Water and sand and sky, trees, fragments of past time. You glance down to check the time; the sun is hardly a clear indicator of where it stands. e watch is a stainlesssteel casing with two mother-of-pearl watch faces—it was a gi from who? i dont know. how? it was a gi by someone, wasn’t it? a gi cannot exist without its creator. then do i exist?

A blank face is what is displayed, an absence of time. A jolt of terror runs through you. Nobody, nowhere, knows what time it is.

but a eld of light and oscillating matter, wrapped in a scarecrow silhouette of shirts, jeans, and sneakers

Signs of any civilization had long passed; you had probably walked past them while being submerged in reminiscent thoughts. e shrieks of the birds above as they rotate lazily in circles and the distant ocean crashing over reefs almost sound like holiday tra c.

i feel as though i am approaching the end of the world. is that so?

and yet, the world is still so beautiful.

hm.

Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister on the bank, when suddenly a White Rabbit with pink eyes ran close by her.

“Oh dear! Oh dear! I shall be late!”

She ran across the eld a er it, just in time to see it pop down a large rabbit-hole under the hedge.

e rabbit-hole went straight on like a

At the bottom of the rabbit-hole, she found herself face to face with the Rabbit.

e Rabbit shrugged. Nothinggoesexactlyhowyouexpectitto.Now, choose.

In another moment down went Alice a er it, never once considering how in the world she was to get out again. isisn’thowit’ssupposedtogo, she said, not quite knowing why she felt that way, the steady ticking of the Rabbit’s pocket watch making her anxious for some reason or another.

Aren’tIsupposedtogettwo di erent choices?

Alice shakes her head furiously, Iwon’t,Iwon’t!

but the Rabbit pinches her nose and forces it down here isn’t where you’re supposed to be brave, Alice, you have to wake up to no good, are you, Alice, her sister scolds

ere is no more Rabbit, and no more magic potions, just her sister on the river bank and an ordinary watch in her hand.

He held out two vials: one labeled “grow bigger,” and the other labeled “grow bigger.” Nowwheredidyougetthatideafrom? Didyounotknowyourfate?Youmustgrowbigger.

e Rabbit pressed the vial against her mouth. Drink, he says. It’stimetostopdreaming,Alice.

and Alice blinks awake from her slumber. Tick, tick.

“Stop being a child, Alice. It’s time to go.”

Mercedes Soledad Rosario gave birth to a beautiful baby boy, or so the nurses said. A er swaddling the infant and counting ten ngers and ten toes, they passed him to his mother, who looked down at his blank white eyes and screamed.

For a week Mercedes lay, exhausted, in the doctor’s shabby cot, listening to her baby’s wheezes. He never cried and he was wholly unresponsive to light, though occasionally he would curl towards Mercedes’ touch. e nurses had no explanation for her—and their sympathy could only go so far. Precisely seven days a er Mercedes gave birth, an infection bubbled up in the village and deposited coughing visitors at the doctor’s doorstep, and then Mercedes and her unnatural baby were alone in the streets again.

e rst thing she did was take the baby to their village’s priest. Father Pérez held him in his long, spindly and hemmed and hawed for a good few moments. “Your child’s eyes are an extraordinary gi he said, and refused to elaborate no matter how much Mercedes begged. Finally the old priest caved and wrapped a string of prayer beads around the baby’s wrist. He looked solemnly at Mercedes and said, “You must pray every day, Mercedes Soledad Rosario, and be more dutiful than you ever have before. As your son grows you must teach him the same. Should God hear, He will be the only one who will be able to help you.”

In the end, Mercedes le the church with the rosary, a new sense of foreboding twisting in her intestines, and a name. Father Pérez had refused to let her leave without one, and so little Gabriel’s breaths rattled so Mercedes’ back as she walked through the streets.

“My life has no place for you,” Mercedes said to Gabriel. e heavy chill of dusk was settling across her shoulders, and he had curled into her chest, his fragile bird bones and the beads around his wrist shi It would be so easy, Mercedes thought, to just make him disappear—to pretend that the last year of fear, vomit, hunger, cold, and misery had been nothing more than a nightmare.

As her ngers tightened around his blankets, Gabriel blinked up at her with his horrible white eyes. Mercedes felt her ugly heart twist into itself, and made her decision. Mercedes and Gabriel slept in a small shack on the edge of the village. Neighbors spit slurs at her in the streets. She couldn’t keep a job. at’s the woman who bore the child of the devil, someone would whisper, and then Mercedes would be back out on the streets, her hands still raw from the latest oor they’d been scrubbing. Still, she made enough for a thin, hungry woman and for a thin, quiet baby to get by.

And Gabriel was so quiet and so thin. He grew as if his esh was struggling to keep up with his bones; his skin looked as if it was constantly stretched taut. His eyes, sunken into his head, never lost their cloudy, blank look. Once he learned to walk, Mercedes could never do

anything without his rattling breaths and clacking rosary beads trailing a er her.

“Blue,” he said one day, so so ly and so abruptly that Mercedes almost thought she had imagined it. Over the years, the occasions he’d spoken were so sporadic that Mercedes was never sure if he was truly talking or if she’d become delusional. is time, Gabriel rocked back and forth on his heels, repeating to himself, “Blue, blue, blue. Snap. Blue.” Mercedes, who had no patience le for him, deposited Gabriel in the care of the wizened old woman who lived next door and went to work.

As she was wringing a more fortunate family’s linens out

had been experiencing pains and coughing blood, but they couldn’t a ord the village’s only doctor and wanted to hear Mercedes’ omens. None of Mercedes’ denials would deter them. She felt her heart twisting between their haunted eyes and between Gabriel, who she could hear inside, turning the rosary beads around his wrist with that distinctive clack-clack-clack.

“Fine,” she said, nally.

Gabriel stared at the empty space to the le of the woman’s head for a good while before declaring, “Firstborn will rot,” horrifying the couple. Nor would he say any more, no matter how much they urged him.

Yet despite that disastrous rst message, people kept coming. Gabriel never grew any less cryptic, nor did his omens become less tragic, but people came to have their worst sins and darkest fears con rmed.

seen him take in years. Eventually he seemed to realize the futility of his e orts and stopped.

And that was when the screaming started.

Mercedes woke one morning to a horrible, guttural sound piercing the air. She was on her feet before she knew it, some long-held instinct guiding her towards where Gabriel slept, and where he was writhing on the oor, screaming.

“Gabriel!” Mercedes shouted, forgetting in her panic that he never responded to her. Even the strangeness of his premonitions had never le him like this. When she grabbed his hands his screaming intensi ed as he thrashed against her hold and tried to throw her o . She managed to wrench his hands away from his face, and screamed at the sight of blood gushing freely from empty eye sockets.

For a brief, unhinged moment, Mercedes was convinced

Our vassal, we called it, the goddess’ gi . Saving our ancestors so long ago,

It was to it that our lives were owed.

Telling us all we needed and all to do,

Without it we’d be lost, forever unable to choose.

It was our hero, our savior, our guiding light, But it was dying slowly, its glow no longer bright. e body of stone was crumbling to dust, e voice of the gods was no longer guiding us.

It sent me away to the goddess’ home,

To nd us a savior out in the world alone. e world it had warned us of and never let us see Still I went, because it was our vassal’s decree

I’d barely le the village when the road split into two. On the right were some trees to hide me from the sun, But on the le was a eld where it was easier to run. Both choices were good and I had no way to choose, So I waited for our vassal to tell me what to do.

It didn’t take long before the voices chimed, ey told me to go le , for I had little time. With their tranquil hum and gentle tone

‘You need to hurry, to bring a new vassal home.’

But on that path I saw a dog in the distance. Its body poised and wild eyes gleamed,

In the walls of the village, it was a danger unseen. It was a reason our vassal told us to stay,

So I turned quickly and I went the other way.

e voices turned sour, rage lled my head, I knew I should do as our vassal said.

ey told me to go back ‘it was the right way’ But I went forward because I was afraid.

e voices continued ooding my mind, I needed food, but they were not kind.

ey would not help when I asked to be led. ‘You should’ve listened’ they hissed instead.

I had nothing to eat, so I looked around, And I’d found berries, plenty, on the ground. e voices would not say if they were safe to eat, Only ‘You should’ve obeyed’ on repeat.

All turned to black, as I tried to choose, I told myself to think of what I could do. But the vassal had given us a list very long, Of what would happen should we choose wrong.

I wanted to repent, to ask for help again, But the voices roared, even louder then. I was saved when I saw a ferret begin to feast, Finally showing me that the berries were safe to eat.

I soon reached the mountain where I could see e temple stood atop, waiting for me.

I made up my mind, I knew what to do, I would not wait for the vassal to choose.

I didn’t need its direction, I didn’t need its aid e night was dark, but my light stayed. e plague of voices silenced, a wild beast tamed, And I knew I was free from the vassal’s game.

In the temple there was no goddess, Just a mirror, surely blessed.

Clearly I could see,

In its re ection: me.

Wait, no. Stop. What? Who did you say you were?

No, you’re not. I’m me.

I’m you.

I don’t know what else to tell you. I’m you. Older you. Don’t look at me like that.

Like what?

Don’t pretend like you don’t know what I mean.

Yeah, okay. Whatever. So let’s say you’re me–

Ouch, could the sarcasm be any louder?

Oh, get over yourself. Can’t believe you’re letting the younger version of yourself hurt your feelings, that’s embarrassing.

So you do understand we’re the same person!

I am so sick of you already.

I deserved that.

As I was saying. Why are you here?

Do you not want me to be?

Well... No, not exactly. I was just wondering if you were here to, I dunno, talk to me for any reason in particular.

I guess I’m here to be, like... your big sister?

Could you be any more cryptic?

Alright, alright! I’m here to give you sisterbonding-sleepover-type life advice, I guess. Like, I’m here to tell you everything I wish I had known when I was your age.

Hm. Okay. Fine. Hit me. What do I need to know?

at we’re both, objectively, pretty bad people.

What?

No, wait, hear me out! It’s okay! Because, well... alright. is is gonna sound bad.

Indulge me, then. What’s on your mind?

You’re old enough to know life is gonna break your heart. It’s happened already, hasn’t it? And I’m sure you’re spiteful because of it. God, are you spiteful—towards your surroundings, towards life itself.

You’re telling me this? You think I haven’t gured this out on my own yet? I don’t need you here for me to realize this, you know that. I’ve been spiteful for as long as I can remember. What, are you telling me now that there’s a better way I could’ve been living my life? I gure out how to get rid of all my problems and poof, all of a sudden I’m drinking green tea for breakfast and doing yoga for three hours a day, is that it?

You could make a preteen writing angsty fan ction cringe with that.

I’m trying to be vulnerable here.

You say that a lot, don’t you?

Okay. Yeah. I’m sorry. ...Huh?

I bet you say sorry a lot.

Oh. Heh, you picked up on that fast. Yeah, I do. I guess I feel it a lot.

Funny you mention the fan ction though. Do you remember that one time in sixth grade when we–

Alright. Gonna stop you right there. Let’s let sleeping dogs lie.

Ha.Anyways. No. Well, yeah. I get what you’re saying. But no. I guess what I’m trying to say is, in a cold and uncaring universe like this one, the most spiteful thing you can do is care. Have hope. Let it drive you. Choose to change your life. Choose to know beyond just who you are now. Choose to look for who you can one day be. If that makes sense.

at’s really existential.

Yeah... growing up is just code for becoming aware of the mortifying ordeal of being known. I guess.

But I feel like if I let go of the spite and pettiness I have holed up in me, I won’t even know who I am anymore. I feel like it’s the only thing I have le of myself.

So who’s the existential one now?

Oh... I mean, was that not the memo?

No! No, I’m just kidding... haha. Sorry. Sorry. at’s not funny. Anyways. Don’t you think it’s about time you nd out who you will become?

I’m not telling you to get rid of your spite completely. at’s not it at all. In fact, that’s probably not even possible unless you’re, like, literally perfect and on the verge of ascending to some higher dimension. Hey, you like music, don’t you?

Years into the future and I see we still can’t stay on a single topic for more than three sentences.

Woah, okay, too much self awareness! Don’t call me — us? — out like that. Whatever. Just answer the question.

Yeah, I like music. You should know that.

Oh, you snarky little– Moving on. So there’s

Man. at’s actually... at’s actually really insightful of you.

a poem by Emily Dickinson. One where she says that “hope” is the thing with feathers. It’s perched in your soul like a little bird, and it sings the tune without words, never stopping at all. She doesn’t say that you never stop hearing the song — only that it never stops playing. e song of hope is always there. Can’t you hear it? e music is swelling. It’s about time you nd out who you will become. It is, isn’t it!

I guess you have a point. I don’t particularly feel very proud of myself, most of the time. But when I look at how far I’ve come... It’s nice.

Yes, exactly! at’s the spirit! Don’t you see how in nite you are?

When you put it like that... Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Okay.

I hope you know I’m always rooting for you.

And not out of obligation. I know you’re trying to communicate something so incommunicable, to explain something so inexplicable. Something you can only feel in your bones, in your blood. But you’re doing good, kid. Real good. I know you’re trying. And that’s all you need to do. Choose to keep trying.

Okay. Yeah. at’s all, I guess.

If you say yeah one more time I’m going to lose it.