7 minute read

the timekeeper’s art

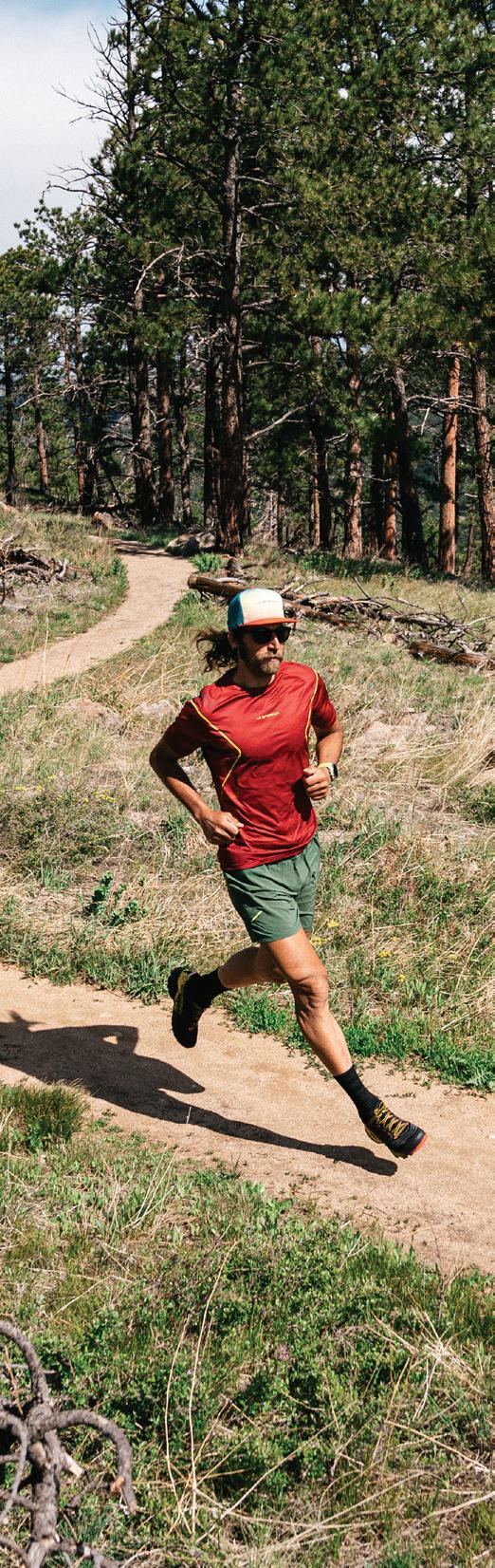

By: Anton Krupicka

Competitive running is a brutally objective world. The whole purpose of the track in “track & field” is to have a precise arena by which to dispassionately analyze performance. The mathematics of athletic value are seductively simple: how long did it take you to run this exact distance? When it comes to contending a record or measuring improvement, the onus is on one thing only: linear, unfettered, metronomic speed.

Advertisement

The mountain environment, on the other hand, is almost the exact philosophical and conceptual opposite of the straight edges and clean curves of a stadium track. Wild, untamed, chaotic and often unpredictable, the mountains and mountain culture–-be it rock climbing or mountaineering— have long been the muse for romantic ideals and the theater for classic human drama. The primary attempt at standardization in technical climbing is to assign a route a grade, which is typically proposed by the first ascensionist, then confirmed through crowd-sourced consensus. How hard do people who have climbed a given route feel it is? There is endless discussion surrounding said grades and sometimes there is ego involved in assigning them. In short, they are unavoidably subjective.

Whereas running around a track has largely been reduced to a science, climbing in the mountains is, even today, still an art where methods and inspiration and objectives are all chosen by the individual and are an expression of that person’s values. There are a lot of different ways to climb a mountain. How you do it says a lot about why you do it; such value-laden analysis is virtually irrelevant in the world of running around a track as fast as possible.

Of course, not all runners are scientists–-far from it—and not all mountaineers or climbers are artists. Not even close. But the tenor of each pursuit is unavoidably tinted by the ultimate goal of each activity—on the one hand, run as fast as possible; on the other, climb in the best style by the most beautiful and difficult route.

In my view, the meeting ground of these two end-members of the perambulatory spectrum is the arena of the Fastest Known Time, or FKT.

Origin of the Term

As far as anyone can tell, this term was coined by the effervescent Bill Wright–-an extroverted Boulder-area engineer, climber and runner (and skier and cyclist and tennis player and writer). He is also the founder and ringleader of a group of athletes who identify both as runners and climbers: the Satan’s Minions. When I first moved to Boulder almost 15 years ago I quickly became aware of this cadre of runner-climber hybrids who would not only climb the Flatirons—Boulder’s iconic backdrop of 500-1000’ rock faces all titled at roughly 50-55 degrees—but would do so without a rope, would link many formations together in a single effort, and would run the approach and egress in an attempt to see who could do it fastest and just how fast. This activity is the ultimate expression of a goal defined by terrain and imagination; distance is an afterthought. Start and finish at a trailhead, run and climb to those summits in the sky, and return as fast as you can.

In its early days, one of the fastest members of the Minions was the equally charismatic Buzz Burrell. Although Buzz’s athletic roots were most firmly planted in running, he was a similar jack-of-all-outdoortrades as Bill, but with an iconoclastic and philosophical yin to Bill’s engineering and timekeeping yang. Ultimately, Buzz and his bookish adventure partner Peter Bakwin (an atmospheric physicist) popularized Bill’s FKT concept by formalizing it in a basic website where such terrain-defined speed records could be tracked.

Why FKT’s?

To me, the mechanics of the record-keeping are not nearly as interesting or important as what the concept of an FKT represents: the wedding of the objective, timekeeping world of running with the more subjective, artistic—and, let’s be honest, adventurous—emphasis on terrain and tactical style found in the world of climbing and mountaineering. It is a unique balance. Climbing is, at its root, an irrational pursuit where choosing the most difficult route by the purest means is the ideal. These are notably squishy standards, even if the activity itself is highly athletic, and thus, prone to formalization. Evaluation of running performance has always been much more objective: a precise distance interrogated by the unwavering stopwatch.

FKTs tend to exist on routes where races aren’t allowed (or the organization of one would be far too onerous), but the line is so pure and obvious in the way it hews to a certain geographic or mountain aesthetic (summit link-ups, circumnavigations and range traverses all come to mind) that it simply begs to be cleaned in a single, concerted push. The satisfaction that comes from pushing oneself all-out to explore a personal limit is still there, but the hoopla and coloring-within-the-lines nature of a race isn’t, even if the preparation consists of as focused a training regimen as it would for a race.

In popularizing the concept of the FKT, Bill and Buzz and Peter were championing the notion that mountain athletes can have it both ways: left brain and right brain. Science and art. Clinical performance and creative interpretation.

A Brief History of My Running Prejudices

My own integration into the world of FKT’s had typical origins—I was first and foremost a runner. I grew up in rural Nebraska. This means that at least 90% of the running I did during my teenage years was on unimproved surfaces—rolling gravel roads, rangeland double-tracks and singletrack cow paths. From the beginning I had a predilection for the toughest, most interesting routes I could devise. While the footing in Nebraska is soft, it is also largely consistent and predictable, allowing for full-tilt linear propulsion in essentially a single plane. As such, I saw myself as simply, broadly, a runner. Not a roadie, not a trail runner, certainly not a mountain runner. Just: a runner.

Even at an early age, it was fairly clear that I didn’t have the talent to truly excel in the uni-dimensional realm of track and road racing. My lack of traditional running success and inherent attraction to high-volume over intensity made it easy for me to eventually become curious about the less exacting scene and more adventurous theater of ultra-distance races staged over rugged terrain. Nevertheless, during my first half-decade of racing mountain ultras I retained a misguided disregard for forms of movement that I felt were (if I’m being totally honest) beneath the Platonic ideal of a runner. Despite several years of being a runner in Colorado’s decidedly more extreme topography, I was still wed to my identity as a runner. To me, hiking and all-limbs-engaged scrambling did not belong in the same rubric as running. My basic philosophy was: if you were good enough, you could run it. If it was too steep or technical to be run, it wasn’t worth doing.

A Turning Point

It took breaking my leg in 2011 to finally abandon such a narrow view in favor of a more expansive perspective of what running could be. In the recovery from that injury I embraced steep, uphill hiking as a legitimate means for getting a workout—the true epiphany occurred when I realized I was able to power-hike some of the classic hill-climbs around Boulder, CO nearly as fast as I had ever stubbornly run them. And I reconnected with rock climbing, a side-hobby that I’d sporadically pursued in college, especially whenever injury would force me to soften my monomaniacal focus on running.

This mindset shift in acceptable movement ultimately precipitated a key change in how I defined my relationship with foot travel. Instead of evaluating all efforts through the clinical, immutable metrics of time and distance, I began to draw inspiration and motivation from the landscape itself. No longer did mileage matter to me. What mattered was the kind of ground I covered in that mileage, and where that mileage took me.

Embracing Diversity of Movement

My daily running decisions were now driven by terrain and topography, not arbitrary distance. Reaching a summit, connecting a series of peaks or traversing a ridgeline all became worthy goals instead of simply covering a predetermined amount of miles. When the emphasis shifts from distance to topography, the form of movement becomes much less important, only that it’s self-powered. Suddenly, I no longer saw hiking, scrambling and climbing as liabilities to my weekly mileage goals. Rather, they were assets in my daily pursuit of achieving topographic high points by the most efficient and aesthetically-pleasing line.

As I sought steeper and more direct routes up the local peaks in Boulder, my eyes naturally turned to the most obvious and imposing manifestations of that ideal—the tall, sheer-seeming eastern faces of the Flatirons themselves. Buzz was my introduction to this steeper, more technical world. We had met five years previously when I had run—and won—my first Leadville 100 in a pair of La Sportiva Mountain Running shoes, the Slingshot. Buzz was the manager of Sportiva’s Mountain Running® Team at the time and, indeed, ever the visionary, had been its primary instigator. He offered me some free shoes and my entrée into the outdoor industry was set.

In 2012, the first season after my broken leg, the concept of FKTs offered a compelling framework within which to find inspiration and to focus my athletic efforts. The shift in perspective and skillset initiated by the previous season’s broken leg combined naturally with my competitive running background and mindset to open up a whole new-to-me world of mountain exploration and athletic expression. I increasingly felt limited and less inspired by the formalized world of trails and races, but still took great joy in pushing myself physically.

In the ensuing years I made attempts on FKT’s that ran the gamut of distance, terrain, and format. Largely off-trail routes to range highpoints, multi-peak link-ups that required continuing through the night, backyard efforts less than an hour in duration, endurance ridge traverses that never dropped below treeline, even some multi-sport objectives that combined endurance and athleticism with technical skill and know-how. In my view, all are fair game and the scope and style of further challenges are only limited by my energy and imagination.

FKT’s Going Forward

The pandemic in 2020—when virtually all formal races were canceled—turbo-charged the dissemination of the FKT into the mountain running community’s broader consciousness. With no races to contend, athletes around the world turned to testing themselves against routes of their choosing, on dates of their choosing. To me, the great gift and appeal of the FKT—and ideally its lasting impact—is this emphasis on individual agency and creativity.

The timekeeping aspect, while fundamental to the concept, is I think a bit of a red herring to the specific approach and mindset that FKTs enforce. It doesn’t really matter who is fastest, but, for me, I know a deeper connection is formed between myself and a place if I am operating closer to my zenith of physical effort. FKTs offer a reason to go to some of the most beautiful places in the world, seek a compelling route, develop a meaningful relationship with that place, and finally, through focused effort, have a rich experience that imparts a durable memory. There is value and reward in striving to be the best version—or, at least, a better version—of yourself. FKT’s provide an apt framework for this fruitful striving.