Sketchbook Contents

5. Woodland Cemetery Stockholm, Sweden

7. Hunts Points Riverside Park Bronx, NYC

8. Vietnam Veteran’s MemorailWashington Mall, DC

6. Mahabodhi TempleBodh Gaya, India

6. Ta Prohm TempleCambodia

5. Woodland Cemetery Stockholm, Sweden

7. Hunts Points Riverside Park Bronx, NYC

8. Vietnam Veteran’s MemorailWashington Mall, DC

6. Mahabodhi TempleBodh Gaya, India

6. Ta Prohm TempleCambodia

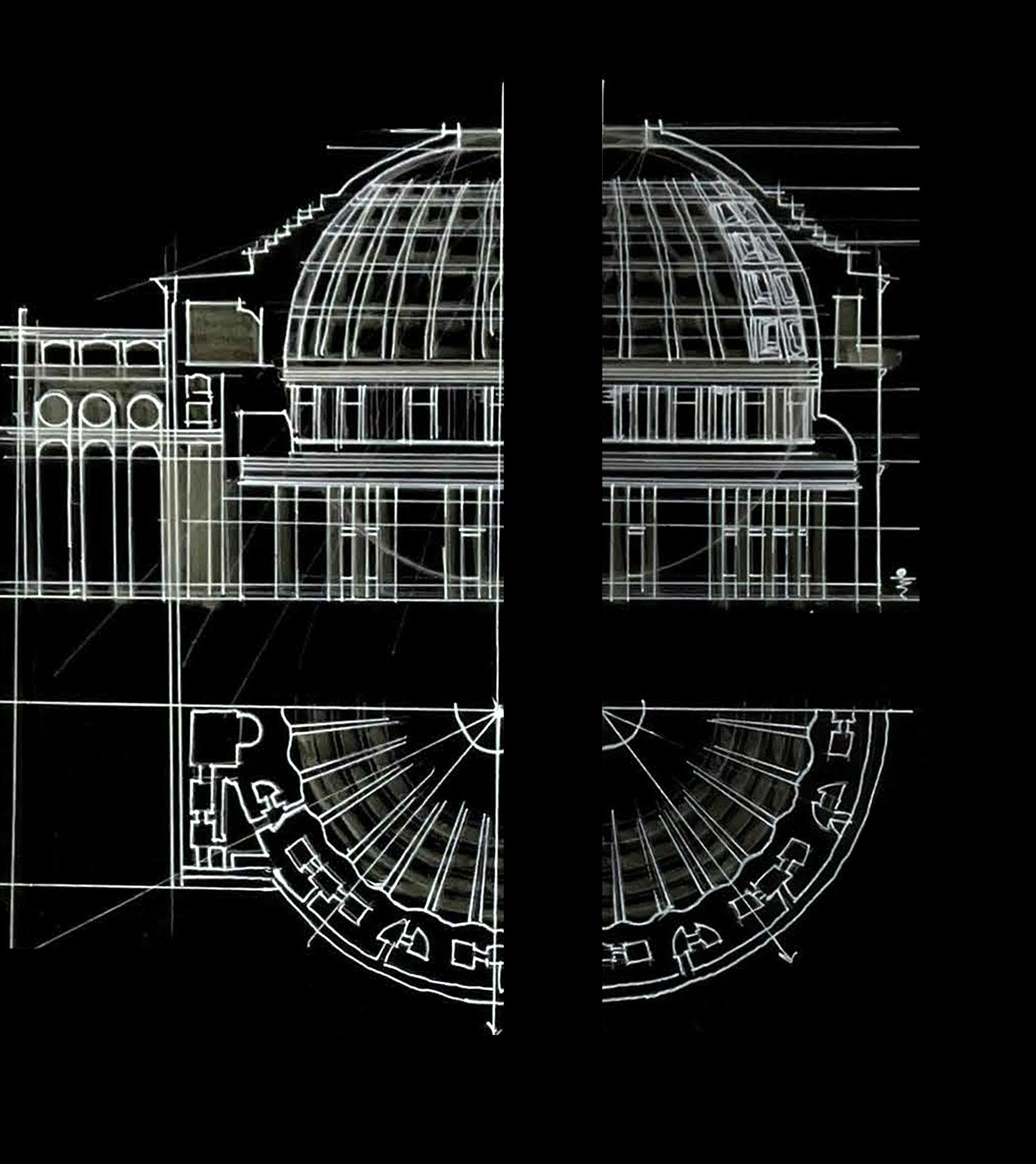

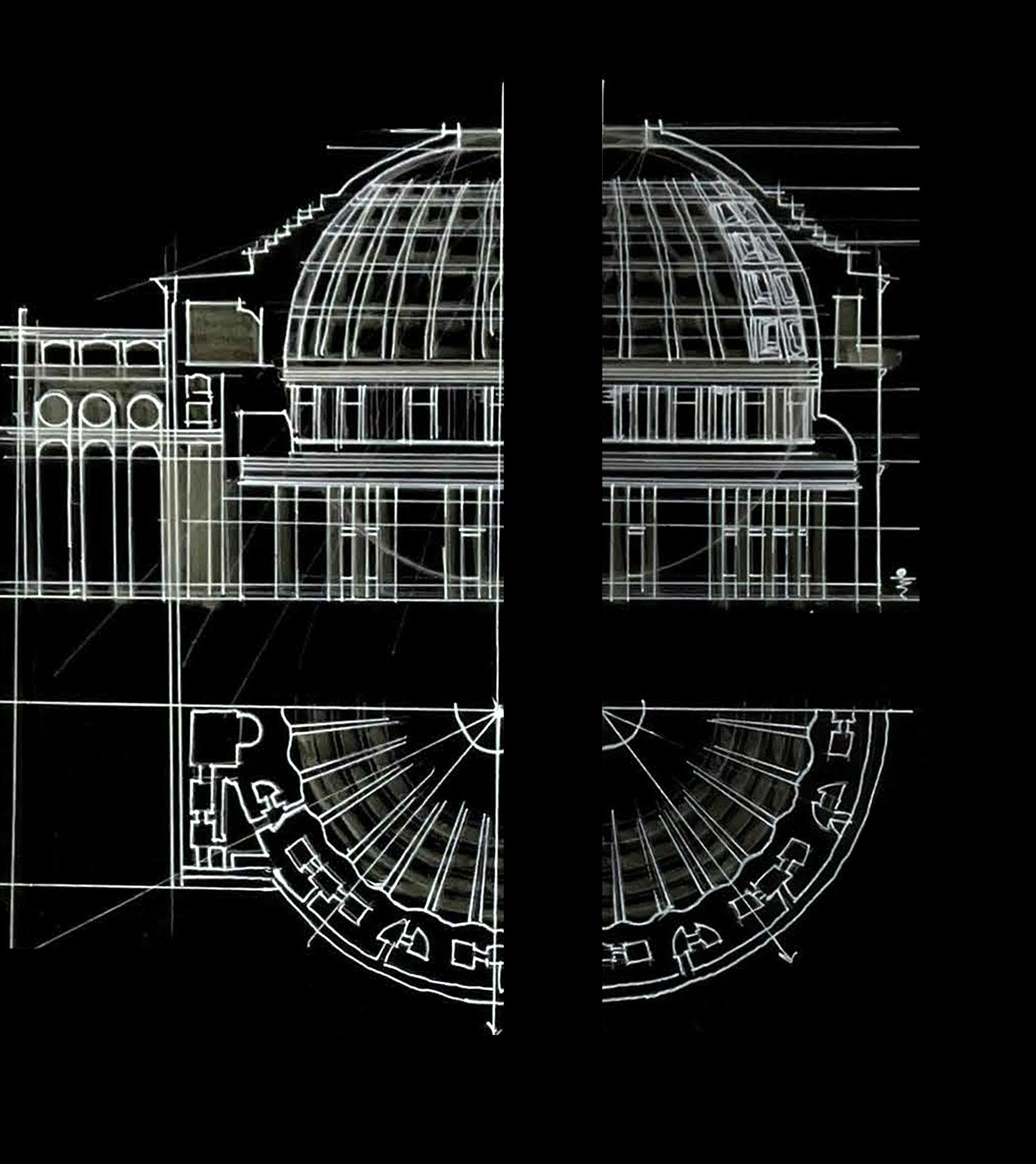

The Pantheon is a timeless work of architecture that exhibits aesthetic qualities in construction, which led me to investigate how it connects our bodies to the ethereal. The illustration begins by understanding the quality of light and how it enters the space from the oculus. The oculus produces a circle of light that projects onto the interior of the building when the time is true noon. The light’s four stages from the rotunda to the floor are the winter solstice, the equinox, “Dies Natalis,” and the summer solstice. “Dies Natalis” is the name of the phenomenon for the rebirth of the sun (in Latin it means ‘birthday/anniversary’), and this day falls on April 21st. This celestial alignment falls perfectly in line with the entrance into the Pantheon. When it is noon on April 21st, the doorway becomes a spiritual threshold due to the way the light is pouring into the doorway. The oculus of the Pantheon becomes an instrument for transcendental moments through the way it “necessitates the assistance of light and silence” (10).

The work “Between Cathedrals” resembles a palatable architecture that is meant to evoke the user in their experience within a space by framing the space. The secular nature of Between cathedrals is through both materiality and form; the architecture is made to stand out as a juxtaposing geometry, but remain silent behind the landscape. The architecture is meant as only a stage or a window to view nature from. These palatable strategies are highly reminiscent of Mies’ Farnsworth House. The Farnsworth is a home designed very simply in order to act as a conduit for viewing nature and its foliage. Two solid planar slabs held up by eight tectonic columns and separated by a glass curtain wall provide framed views of nature. This produces the effect where people are the guests witnessing nature, and this architecture becomes a place of serenity. “Materials that transcend materiality.”1

Medium: Vellum, led pencil, Tombow ABT Watercolor Pen

Vantaa, Finland

In his chapter, Pallasmaa discusses the secular spirituality evoked by architecture, and how sunlight becomes material for the spiritual. Sunlight alters our perception of the atmospheric quality of a space, its form, scale, and materiality. The illustration displays Juna Leiviska’s Myyrmaki Church in Finland to further investigate illuminance as a material, or how to recognize illuminance as a spiritually secular substance. The interior walls of the Myyrmaki church loudly exhibit thoughtful choreography for how sunlight travels across the wall throughout the day. Correlations can be drawn between the Myyrmaki Church and Pallasmaa’s claim, “all material is made out of light.” the built construction of the Myyrmaki church actively diagrams the process in which we conceive light; the material surface casts a shadow; the shadow belongs to the light source; the light is the source of all being. Architecturally, this is done through the pulling and pushing of planes to expose the interior to the sunlight streaming through the skylights. Light is what connects us with the natural realm and the constantly changing phenomena of the sun and cosmos. James Turrell, a spatial and lighting artist, seeks to “capture light and hold it for physical sensing,” as if light were independent materiality or substance.1 Sunlight is the subject of Leiviska’s church, and not only defines the atmospheric quality of the interior, but the rhythm influences how the space should be respected. Turrel captures moments in time when sunlighting is perceived as substance – his sculptures act as photographs of everlasting lighting. And similar to a photograph, the Myyrmaki church repeats the same sunlit rhythm and cadence across its walls.

The properties of Turrell’s diffused light equating atmospheric weather conditions (fog, rain, shine) change the characteristics of the material light. Another piece of architecture that emulates the practice of light as a substance is Le Corbusier’s Notre Dame Du Rampchamp in France. Andoni Karaklas paired Le Corbusier’s chapel with Turrell in how both engage with color to alter the atmospheric quality produced by light. Le Corbusier choreographed multiple moments for different times of day within the interior of the chapel, and these moments are directed by colored and tapered apertures. How lighting is treated as a captured moment-in-time substance within Rampchamp emulates the characteristics and photographic qualities of captured light by Turrell.

Junahi Pallasmaa chose to compare these precedents and artists to create a network between different artists that exhibits light being used as a substance or material. Architecture is revealed in counterpart with its surroundings and is heavily influenced by its environment. Within all of these sacred architectural sites, sunlight is the muse of the project, and every architect uses multiple techniques to capture and disperse lighting. Pallasmaa’s listed architects dual as both designers and photographers of lighting; composing moments of lighting in a space.

Medium: Vellum, led pencil, Tombow ABT Watercolor Pen

Partner - Gabriel Blake

Different people can synthesize a specific place as serene or spiritual, whether or not it yields a religious connotation. Many individuals who visit these places, however, cannot articulate how the environment is performing. They are only aware of its harmonizing nature with human senses, and how it silences them. Vincent Scully compares works of architecture that polarize on the historical timeline of precedented architecture. The sacred timeline illustrated on the beside page categorizes the architectural characteristics of a space that evokes silence or spirituality. Overlayed in a bee trail is the chronological timeline that connects with the new timeline network.1

The timeline begins at Stonehenge and ends at the Myyrmaki Church in Finland. Additional arrows cast how our phenomenological strategies cannot be categorized according to era. The timeline beings with the depiction of an arrival; viewing the personified architecture from the afar view planned for the user; the Acropolis in Athens, Greece, and the East Rock Outcropping in New Haven, CT. The network descends into architecture that interacts with the Earth and the sky. Architecture can both juxtapose and complement the landscape. Light has always been an entangling feature in architecture that aids in defining space and spacial qualities. The light and the sky have been what have motivated civilizations to build up from the ground and reach the sky; the empire state building in new york city and Temple 1 in Tikal, though predating the skyscraper by 1200 years, both aid the fulfillment of extending our beings towards the sky and the cosmos. Scully capitalizes on this phenomenon because it symbolizes the human perception of divinity and unity for architecture built toward the cosmos.

The Pantheon of Rome serves an architecture that serves many phenomenological qualities of architecture; geometry, light as substance, threshold, and celestial connection. More details regarding its phenomenological ties to the characteristics of spiritual architecture have been laid out in my first analytical sketch. The way humans used to conceive architecture was through the landscape, and how it connects to the body. Now, we find phenomenological qualities of space articulated by light in both ancient and present secular architecture.

Different people can synthesize a specific place as serene or spiritual, whether or not it yields a religious connotation. Many individuals who visit these places, however, cannot articulate how the environment is performing. They are only aware of its harmonizing nature with human senses, and how it silences them. Instead, we might find it much easier to distinguish spaces we are repelled by and nominate characteristics that produce spiritual space. A typology chart that simmers-down

Medium: Vellum, led pencil, Tombow ABT Watercolor Pen, Adobe Illustrator, Photoshop, & InDesign

the spacial ornamentation of every historic piece of architecture can help designers figure out what qualities make it transcend into the present. The typological form of the interior space created by the architecture can be distilled into trapezoids for the Parthenon, triangles for central-American and Egyptian pyramids, a circle for the Pantheon, and so on. Secular architecture can be analyzed through very different avenues, such as the impact of light, stereotomic material, or geographical orientation; their graphic successfully synthesizes the relationship between an articulated space and the human body.

Stonehenge, UK; Temple of Apollo, Athens, Greece; Unity Temple, IL; East Rock Outcropping, Connecticut; The Acropolis, Athens, Greece; Temple 1, Tikal, Guatemala; Empire State Building, NYC, USA; Abbey Church of St. Marie-Madeline, Vezelay, France; Pantheon, Rome; Notre Dame Du Haut, Ronchamp, France; Myyrmaki Church, Finland; MIT Chapel, Cambridge, MA, USA

The human body is the summary for “here and now,” and yet we pay no attention to our bodies’ relationship with the environment. Ando slows our focus to better experience the now by producing Shintai architecture. Within this connotation, Shintai is mean the relationship the body has with space; the way our body perceives the built environment through sense.

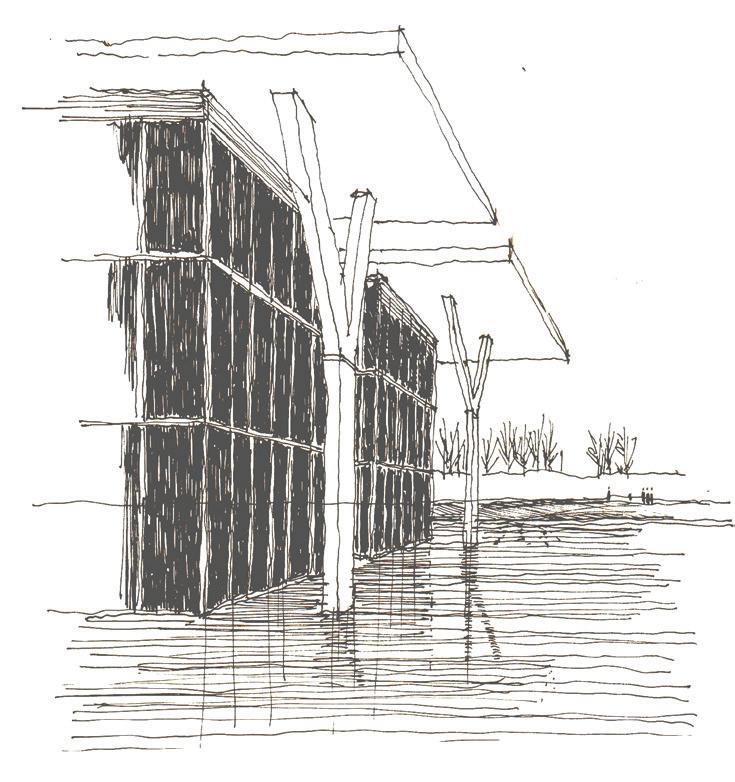

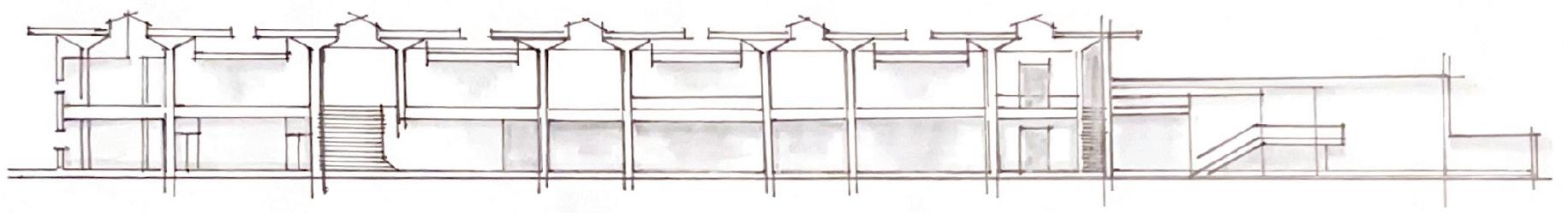

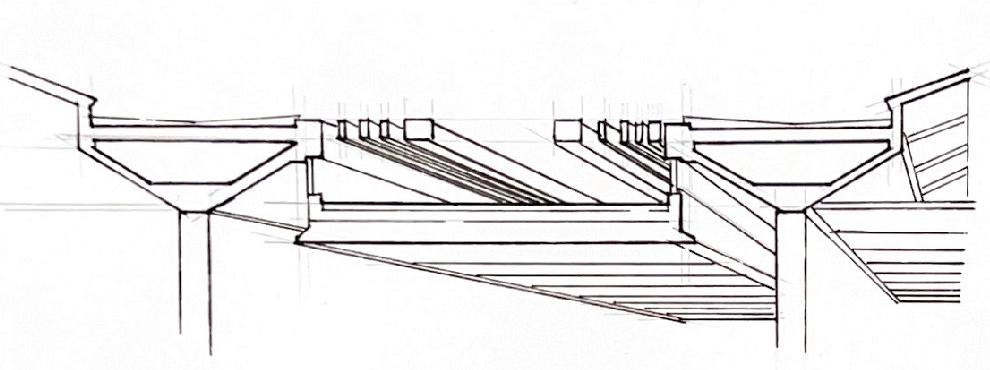

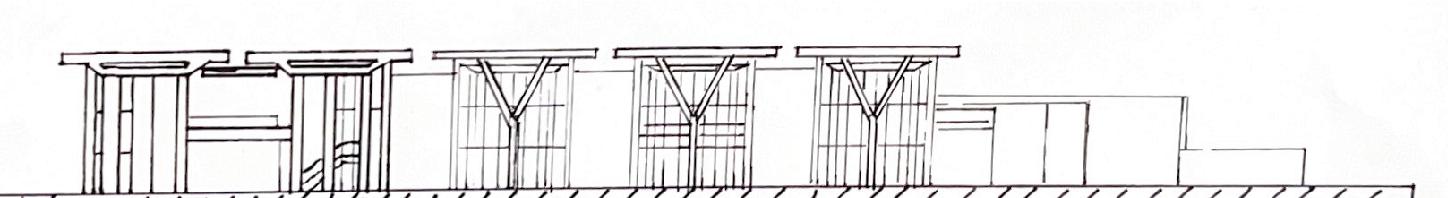

Located in Fort Worth Texas’ cultural district are a handful of notable art museums designed by highly regarded architects, such as Louis Khan’s Kimbel art museum, Philip Johnson’s Amon Center, and Tadao Ando’s The Modern. Ando recognized the relationship these museums had with one another and therefore proceeded with a design concept that is sympathetic in dialogue with Khans Kimbel art museum. The art museum as described by Ando is a building within a building; a lantern above the water’s surface; an arbor for art. The structure is in yin and yang with both the tectonic and the stereotomic. The iconic symbol associated with the modern art museum is a series of five large-scale Y-column structures. The 40-foot tall columns embody a growing tree, or a reaching swan; personifications in nature. The Y-columns support the massive concrete-slabbed roofscape that cantilevers over the entire museum. Stereotomic characteristics of the building’s identity are juxtaposed by a fragile curtain wall facade. The modern elevation reflects shintai by “introducing nature and human movement into simple geometrical form.” The timeline demonstrates simplicity in geometry in our model study. The curtain seals the soul of the body like an envelope.

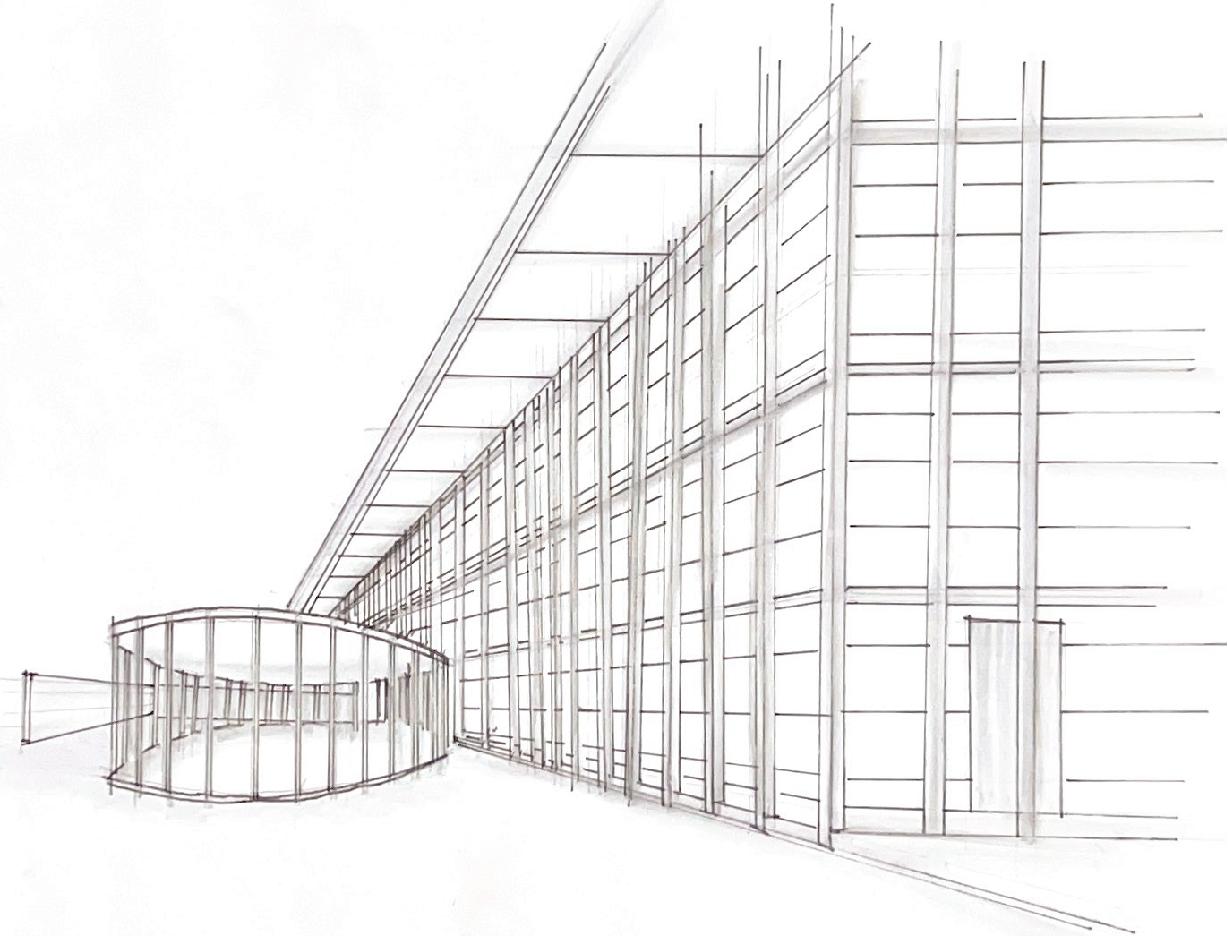

The grand curtain wall is held up by tectonic steel and glass, visually dismissing the barrier from the outside. By manipulating reflections from water views and the ferrovitreous structure, “visually, there’s no barrier between the inside and the outside. There is, of course, a physical barrier made from glass and steel that protects an individual in a conditioned environment. However, the lack of boundaries is heavily influenced by natural light.1

Ando sees light as a dimensional body that we as humans are in constant interaction with. Naturally, lighting visually connects us to an awareness of ourselves in this world, and this experience can be summarized within the entrance of the museum alone. With a limiting view, The minimalist selection of the building construction materials was intentional due to Ando’s belief that architecture should stand silent behind art and nature. Ando frames the view with walls of daggering concrete that tell the viewer exactly where and how far they are allowed to look.

Partner - Gabriel BlakeTadao Ando painted a sacred way that leads visitors on a journey to the arrival of Buddha. The sacred way is the choreographed movement a visitor will take that guides them to the sacred monument. Approaching from a distance, an individual is led by the folds and dips in the landscape. Their eyes follow the concentric rings of lavender plants to the peak of the tallest mound within the rippled terraformed landscape. The hill of lavender is similar to an ancient pyramid in how both terraced monuments mimic the landscape. Ando chose lavender to fuel how “man articulates the world through his body” by drawing attention to how the scent of lavender centers us to our bodies. This tallest mount is Tadao Ando’s Hill of The Budda. Tadao Ando buried the monumental statue of the Buddha in a concrete cavern, with dirt added on top to present the dome as a piece of the existing landscape. An oculus exposes the head of the Buddha to the sky. As an individual descends toward the threshold of the Hill of The Buddha, the exposed head slips out of sight and is eclipsed by the terraced dome. Ando framed sight lines by terraforming the landscape that tells the individual how far, and where they are allowed to look, whether for suspense or contemplation. The passenger slightly descends to the immediate arrival of the monument. The dome’s entrance is low and the cold atmosphere from within juxtaposes the open and bright air above. The cavernous entrance swallows the entering sunlight. Natural light becomes a method of wayfinding that allures the body to the statue of the Buddha. The concrete materiality of the walls produces a reverberation of every little sound, begging for silence whilst entering. The concrete makes the statue feel as though it was carved out from the rock of the Earth. After stepping forward, an individual’s eyes focus on the beacon of light penetrating its way into the cave where the statue of the Buddha lays. As an individual circulates from one interior space to another, they are met by both ceilings and walls cast in concrete. Ando’s intention for the architecture was to stay silent behind nature. Silence to Ando does not mean planar walls; instead, he designed the concrete to be cast with bends and folds to catch the atmospheric qualities of natural lighting. Sunlight diffuses naturally on the textured walls and interacts with the architecture harmoniously.

Time, Memory & Silence - Wentworth 2023

Team - Gabe Blake and Laura Pease; Professor - Meliti Dikeos

Architect - Tadao Ando

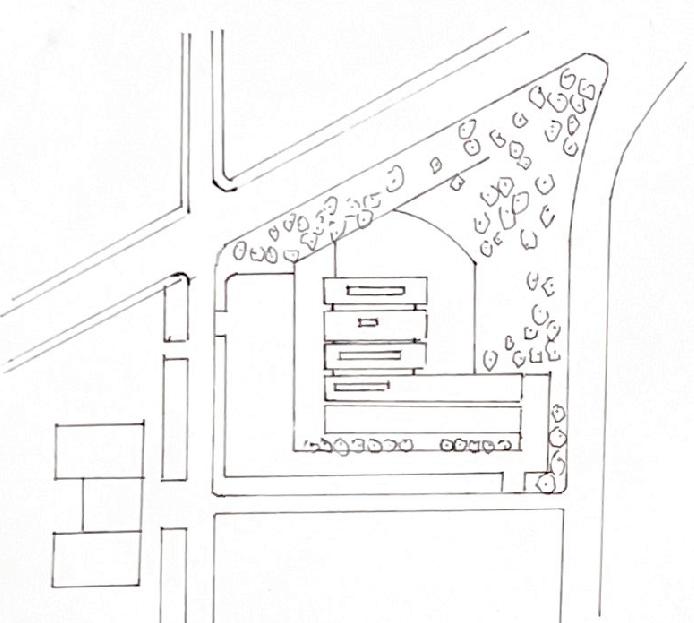

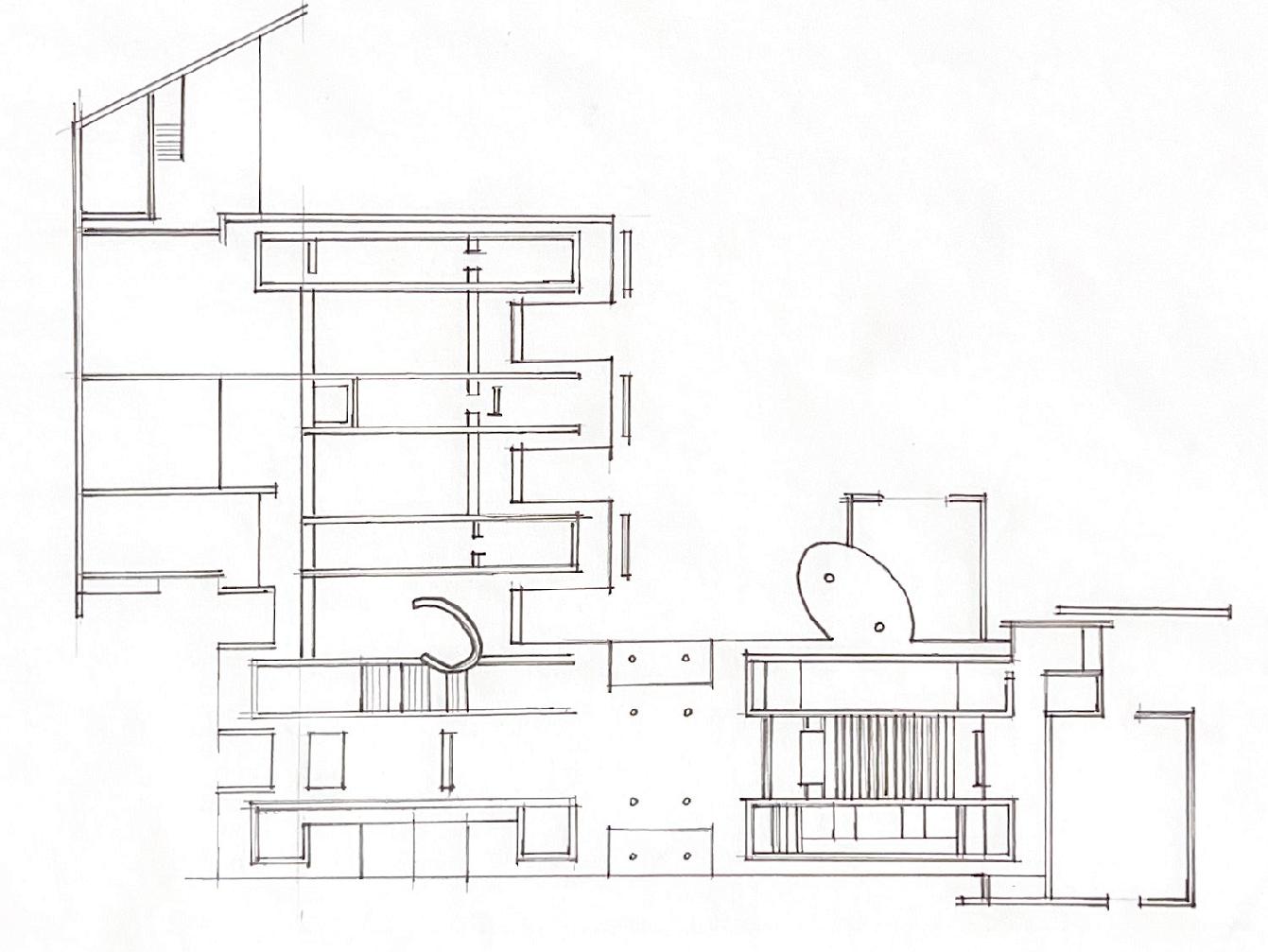

Spacial/Site Plan

Location - Fort Worth, Texas

"An Arbor For Art"

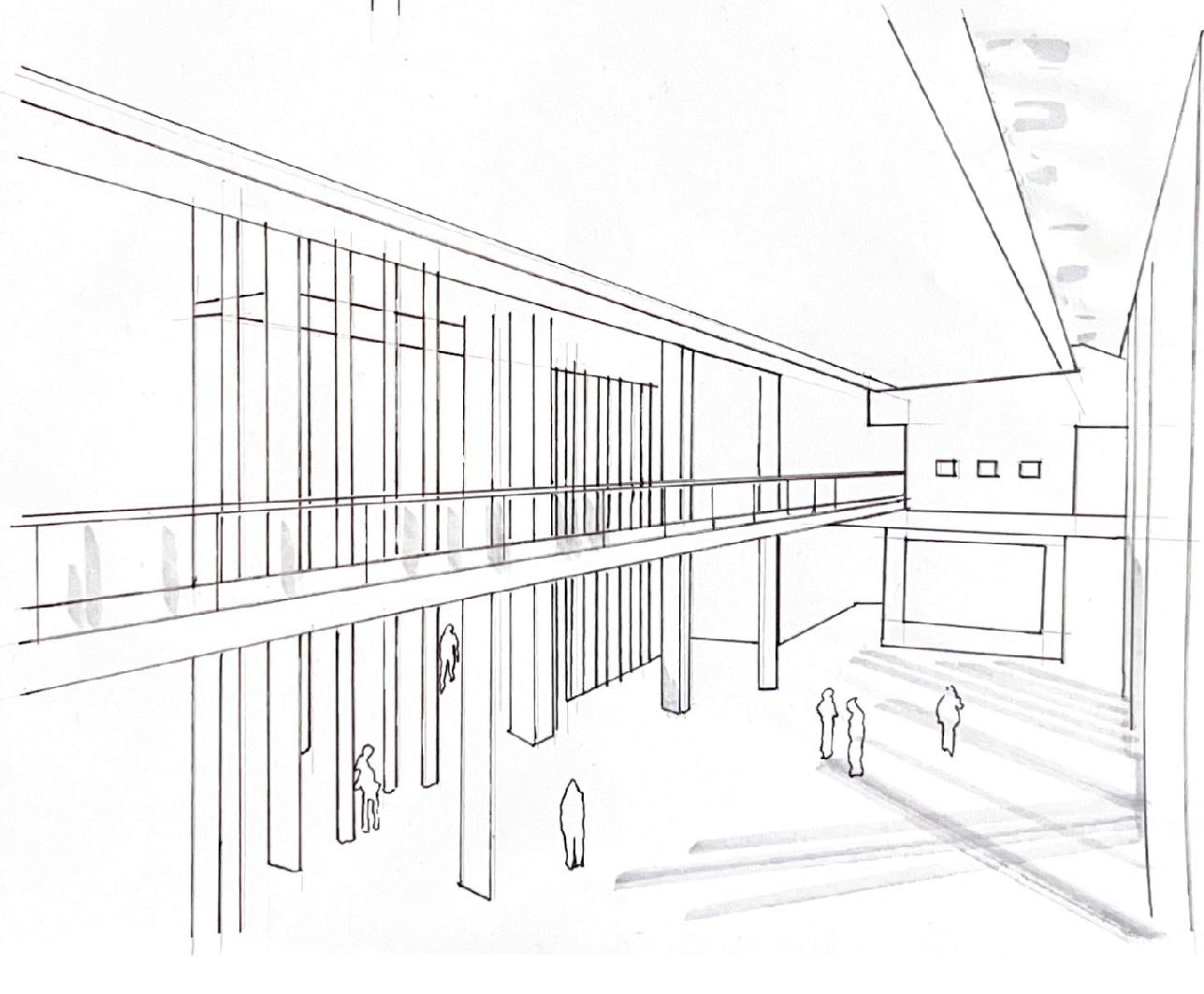

Interior Perspective

The building appears as floating lanterns on the surface of the water.

The chief curator Michael Auping worked closed with Ando to ensure every piece of artwork would receive adequate lighting conditions. Ando introduces both reflected and diffused light in the gallery spaces.

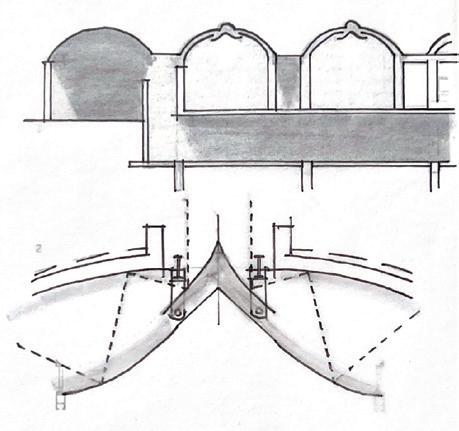

Modern Ceiling Section

Ando Was chosen amongst six other notable architects but was chosen due to the way he designed a building concept that was sympathetic with the dialogue presented by the Kimbell Art Museum. Ando introduced a similar deliverance of diffused light in the Modern Art Museum.

Exterior Perspective

Section A

Tadao Ando - The Modern Museum Precedent Study

Kimbell Ceiling Section

Exterior Perspective

Influenced by Japanese techniques for simplicity, Ando designed with a simple materiality palette and formed the materials using simple geometries to better incorporate the natural environment.

Geometry

Ando describes The Modern as a building within a building. An outer 3-story glass curtain wall surrounds the inner concrete gallery walls. Cantilevered cast-concrete roofs are supported by large Y-column 'forks.'

Section B

Building Plan

Heavy Space Light Space

Team - Gabe Blake and Laura Pease; Professor - Meliti Dikeos

Model Images

Medium: Bass wood, Arcyllic, Super glue, Lazer cutter

The site for the Woodland Cemetery in Stockholm began as an old gravel pit. The existing land use of the site challenged designers both conceptually and physically; how can one turn an industrial wasteland into something sacred? The site has a high point in the landscape where the central clearing is visible “above the site’s periphery, creating a physical void where key elements of the cemetery emerge.”1 Architects Gunnar Asplud and Sigurd Lewerentz designed a wall that separates the sacred cemetery from the profane forest. Within the forest clearing, the individual is brought to a pause to observe the sky above. The cemetery provides an example of “the archetypal power of the forest and clearing for contemplative” and numinous space.

Upon approaching the entrance of the Woodland Cemetery, the user finds themselves walking along a cool-toned stonecoursed wall preventing them from knowing what happens within. While continuing down the path of pleached trees, a sudden opening within the wall appears. The stone wall folds into a half-circle, with its midpoint leading to the entrance of the cemetery clearing. As the individual gently ascends through the entry, their movement and eyes are directed only forward. A temple facade tucks itself into the left wall. Its architecture both compliments and contrasts the surrounding material, but ultimately is desolate to the remaining cemetery. The temple frames another stone face not composed of the same coursing as the first wall. This stone resembles a cyclopean bond; a stone coursing that is constructed with vertical rock joints to produce a sense of the sublime. These rock joineries are reminiscent of the construction methods that were once used in the sacred city of Macchu Picchu; the workers would carve the stones to niche into place with one another. This enabled the buildings not to be glued together by mortar and therefore dance in place during an earthquake. Water flows down the face of the rock, creating a miniature ecosystem with flora, and affecting the coloration of the rock face. Framing these are columns of Nordic classicism.

The reflection garden at Blodel Reserve is framed as a room within the forest, with a window to the sky. The room of the reflection silences the individual and brings one in tune with their senses. It is comprised of ground, water, plants, and sky; each in its elemental form. The site of the reserve lies within a primordial forest, located on Bainbridge Island, Washington, US. Although it is a contemporary garden, it was inspired by Japanese lineage and traditions surrounding meditation, connection with nature, and inner reflection. The space is entirely contained within the hedged precinct that is defined by the water. A horizontal view of the borrowed scenery that surrounds the garden. The concept behind borrowed scenery

Medium: Vellum, led pencil, Tombow ABT Watercolor Pen

is not only for the framed vignette but to produce a comparison between the miniature and the small, and the small brought near. Yew hedging is planted around the perimeter of the pool to not only built the room but as well to clip out the view of the messy forest floor covered in dead branches. The corners of the hedging don’t touch, and this is where the user enters and exits the garden. The hedging acts similarly to the concentric fencing at the Ise Shrine in Japan; creating different boundaries that one can and cannot pass through. In addition to providing a window towards the sky, the water within the pool resembles a stillness in nature. This is then later juxtaposed with the bird sanctuary; a social and louder communion with nature.

Many of Richard Haag’s gardens within The Bloedel Reserve were inspired by the narratives of numinous and sacred spaces. While within Bloedel Reserve, the user is meant to transition their movement between gardens of meditation and meander through pathways into the deep forest. A sense of destination, changing places, and hidden and revealed approaches throughout the journey in conscience within an individual. The rhythm of the forest suggests a slow-medium speed of movement, and the trees stand tall and proud like people. A sense of destination is accomplished when the user crossed the threshold; a level change into the reflection room produces feelings of ascension, while the changing lights and shadows equally demonstrate a passing through spaces. Haag capitalizes on the relationship between man and nature. In his lectures, Haag would never share a real aerial view with his students of the reflection pool itself. This was because the juxtaposition of geometry and nature intertwined with phenomenological water qualities produced a perception of the space that is unique to every user. The pool juxtaposes nature through its manicured straight lines, and the simplistic design presents a more meditative space; even the benches were changed to remove distractions. Using geometry as a counterpoint in the reflection room personifies the reflection garden with its complement and contrast of nature, unique to the multiple gardens at the Blodedel reserve.

1. Rebecca Krinke, “Nature, Healing, and the Numinous”

The Sleuk Rith Institute brings sacred and spiritual vocabulary into the contemporary era. The building’s massings are inspired by the Cambodian landscape it resides in and reflect the architectural mantras and practices of ancient Buddhist architecture. The Sleuk Rith Institute is a sacred place, or Tirtha, of its time. Designed by Zaha Hadid in 2014, the sophisticated research center elaborates the words from the Buddhist faith to represent a modern interpretation of our evolving cultures. The namesake for the Sleuk Rith Institute is derived from the dried leaves that are named Sleuk Rith. These dried leaves are native to the geographical region of Cambodia and had been used for centuries as a tool for documentation. The importance of documentation of knowledge is emphasized as the Institute’s goal, therefore is how the institute received its namesake. The way we understand history is not only through documentation but also through the site. The site was once the location of a High School that had unfortunately been bombed during Cambodia’s devastating wartime period. In reflection of the site’s sacred historical context, the program of the building is made to support five main functions: a research center, Grad School, Museum, Archives, and Library. The building stands within the landscape as a landmark and draws an individual toward its grandeur. It is surrounded by five large-bodied reflection/retention pools; five to complement the five building masses. Between the ponds is the only visible linear path into the building. Otherwise, there are no main axial pathways that bring the visitor to the front door. Instead, individuals are led to the building’s entrance by ‘desire lines’ that weave within the landscape. The choreography of movement is the only gesture made for an individual to arrive at the site. While meandering through these arrival paths, the attention of the individual is focused on the whole environment around them. One’s eyes are left scanning the forestscape beyond.

The Shikara, or the peaks of Mount Meru, are emulated in much sacred Buddhist architecture that inspired Hadid. The temples at Khajuharo are architecture that emulates these mountain peaks. From the exterior perspective, the shapely characteristics of Meru’s Shikara are seen by the individual. Within the interior of the temple, the experience is a cavernous one. The mountain’s peak governs a cave-like chamber below, the Garba Griha - the innermost womb chamber of the temple that is said to be the embryo of life. The Sleuk Rith Institute takes inspiration from these temples and Buddhist architecture alike and brings the characteristics of this large scale into the building’s wooden structure.1

Shui, or water, is captured by the Institute’s large retention ponds through a capturing system. Besides their technological function as a greywater system, the retention ponds act as an

Medium: Vellum, led pencil, Tombow ABT Watercolor Pen

instrument for jyotirlinga - the manifestation of visible light. “Light is not the Ambiance of seeing but is the icon of Tirtha” itself. Sunlighting embodies the invisible threads that tie the highest heavens to the ground of Earth. Within the Institute, natural lighting is framed to exhibit the phenomenological qualities of light and sky. The architecture “contains what heaven and the highest heavens cannot contain,” which is channeled through earth and geometry. The structural form of the Institute complements the environment further; Hadid’s parametric architectural design emulates natural forms by using geometry. The beauty of this site is how the architecture made by humans yields to nature and instead gives into blending entanglement. The melting of nature into the architecture was made intentional, however, through time, the architecture has completely surrendered to the forestscape melting into its seams. The institute inverts the direction of melting wood and directs verticality upwards. If ever constructed, this site would be a precedent for contemporary Buddhist architecture and more.

Upon an oblique aerial view, the Ganges River is seen framed by geometric architectural stone-stepping. When seen in elevation, many traits of the city of Varanasi’s facade along the water can be nuanced. The framed geometric stone stepping that perimeters the coastline steps down into the water. The scale of the steps emphasizes the Tirtha of the river Ganges, and one’s sacred descent. There are many typologies of how one may descend into the water, and what sacred rituals or daily routines one might perform. Examples of these uses include large-scale public events, like hosting masses, events, or ceremonies. Daily routines would include chores like washing clothes. Many temples sprinkle the skyline of Varanasi like stars in the night sky, giving its nickname the city of temples.

Hunts Point, Bronx, NYC; Santiago, Chile

Chapter Author - Michael Sheridan Architect(s) - Alejandro Aravena; Bruner Foundation, Inc.Integrating value and concepts of the ‘numinous’ provide equal opportunity for all citizens to have equal access to the assets of their city. Spirituality is considered “a process of human life and development focusing on the search for a sense of meaning, purpose, mortality, and well-being;” in relationship with one’s self, others, and the universe. The Bicentennial Children’s Park designed by 2016 Pritzker prize winner Alejandro Avarena both respects and takes advantage of the topography in the site’s existing condition. Before the construction of this adult & children’s playground, in Santiago, Chile, there was nowhere for an individual to take a long leisurely walk without being interrupted by a street. Alejandro’s Bicentennial Park answers directly to Martha Nussbaum’s notion of the “thresholds” required by everyone to pursue a dignified and flourishing life. In particular, the pillar of “play” is heavily felt in this place. This is an individual’s ability to laugh, play, and enjoy themselves.

Martha Nussbaum emphasizes the interactive nature of social human justice and stresses that the capabilities are “not just abilities residing inside a person, but also the freedoms or opportunities created by a combination of personal abilities.” She further comments on how some living conditions deliver life to people that is worthy of their human dignity, while others neglect these needs. She goes on to discuss the notion of an individual’s “threshold” into a just society, and how this threshold is identified by one of the ten required capabilities: life, bodily health, bodily integrity, senses & imagination, emotions, practical reason, affiliation, relationship to the world, play, and one’s control over their environment. The numerous must be accessible to all people, which is why to aid those most marginalized by society, designers must design within the margins of the city.1

Architecture impinges on spiritual growth when it limits the individual and presents boundaries within the built environment. The Hunts Point Riverside project located in the Bronx, NY, galvanizes community and ecology by removing conceptions of boundaries and transforming the edge of a city as a destination. The project transformed a degraded industrial area into an ecological community sanctuary located on the waterfront of the Bronx. In many cities, the harbor is zoned for the water-dependent industry due to the harbor providing many main economic benefits both for the city and federally. However, this has led to a decline in the environment, on an individual’s spiritual growth, and has created boundary conditions within our built environment. Not only does the project address the needs of both the

Medium: Vellum, led pencil, Tombow ABT Watercolor Pen

to be. This project galvanized the community in its ability to make a dramatic change by providing access to the waterfront and connecting back to more neighborhoods. Our society has suffered the consequences of severing ourselves from nature, and Hunt’s Park takes initiative to reconnect the city to the coastline.

Washington, DC

Designer - Maya LinThe city of Washington DC inquired for there to be a memorial added to the mall of DC that commemorated the victims and survivors of the Vietnam War. Memorial architecture in post-WWII Washington transitioned from monumental to universal architecture to prioritize the symbolism behind the survivors’ loss rather than celebrating a victory. These types of architecture are unique in that “it is one of the few types of architecture whose fundamental function is not to shelter but rather to feel and to remember.”1 Washington wanted a subtle design to respond well to the landscape of the chosen site. The site for the monument was chosen under the guidance of the National Parks Service, and a design contest was organized for candidates to anonymously submit a memorial design. As a part of the studio curriculum, a professor at Yale organized a project in his architectural course where every student of his would submit a memorial design for the new Vietnam Memorial competition. Maya Lin, who was taking his course submitted her design. Although she received a B for a grade, she was the announced winner of the competition, beating over 1400 competitors - that included both her classmates and professor, who also submitted a design. Maya Lin has mentioned in interviews how she wonders if she would have been selected if her submittal was under Maya Lin, instead of as an anonymous contestant with a number.

As a part of her design, Maya Lin responded well to the commission’s inquiries for both a subtle memorial design and an apolitical symbol. She created an unchanged monument of moving composition, and by doing so respected the topography of the site. Her design “Uses traditional forms of sculpture and monument dotted around a landscape.” The descent towards the origin is slow and is best understood by moving through the site. One’s movement is directed intentionally to arrive and depart towards the site from two paths led by the wall’s faces; no other paths of arrival are permitted on the lawn of Washington Mall. Maya Lin’s design resembles a “striking gash” in the landscape that remedies Washington’s inquiry for a non-sheltering nor monumental architecture. The subtle design by Maya Lin makes the whole landscape feel manicured and intentional. In an aerial, the memorial points like a compass towards more monuments within the mall. The two arms open 125 degrees; one towards the Lincoln Memorial, the other towards the Washington Monument. Although her memorial design is meant to be apolitical with its lack of patriotic symbols, each arm is oriented toward another monument within the Washington Mall that is a reflective part of America’s Political History. How the site is used and visited today by new generations is how the experience of the Vietnam War is brought into the present. The names of every victim from the war are written

Medium: Vellum, led pencil, Graphite Pencil

on the faces of black stones that are hung from the retainment structure. The names of the victims are not written in alphabetical order, however; the names are listed chronologically by the date of their death. The act of tracing a loved one’s name that is engraved into the wall is a personal way for every visitor to both engage and interact with the wall. Paper slips and pencils are provided for visitors to bring a piece of the wall back home with them. When an individual approaches the wall’s face of the wall to better read its names, one can see themselves very vividly through the reflection of the wall. Seeing this reflection feels like peering into the looking glass, and witnessing a world where the fallen victims exist. The monument was constructed for the victims of the Vietnam War. The monument was intrinsically needed to validate the emotions of the victim’s families and provide a public place to grieve with others who empathize. Maya Lin’s memorial provides a place where “one can remember, mourn, and try to make sense of intangible emotion….humans have always needed something permanent and tangible to make sense of loss,” and by providing an abstract landscape to make sense of the loss, victims are able to physically connect with both past and present.1

1. Peter Eisenman, “Is there a religious space in the twenty-first century?”