7 minute read

PANDEMIC HEALTH HEROES

F E E L I N G good

PANDEMIC H E A LT H HEROES

Advertisement

As Covid-19 began invading America’s most densely populated cit y, the 47,000-plus s taf fers at NewYork-Presby terian Hospital prepared as best they could for an onslaught. Meet three caregivers who fought the fight of our lives.

MARIE-LAURE D. ROMNEY

EMERGENCY MEDICINE PHYSICIAN NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center

On January 21, as she heard reports of Seattle’s first confirmed Covid-19 case, Marie-Laure D. Romney, MD, thought about New York City’s packed subways and sidewalks. She realized it was only a matter of time before the emergency department (ED) she oversaw at the Allen Hospital, a 200-bed community facility in Upper Manhattan, would be overrun with coronavirus patients. To prevent the overloading of hospital systems and the spread of infection in close quarters, she and her colleagues would have to completely reimagine the ED. And they’d have to do it fast.

After some preliminary discussions, Romney’s team officially met in early March to determine how they would handle the isolation and ballooning volume of Covid-19 patients. And as the outbreak picked up speed in mid-March, it was time to put their plans into action. First, a wing of outpatient rooms was converted into a respiratory unit where critically ill patients were housed together. Romney assigned staff specifically to the unit, which allowed them to work more efficiently and extend the life of their valuable personal protective equipment, since they wouldn’t have to remove it to treat the uninfected.

As coronavirus cases proliferated, an open treatment area was transformed into an additional pop-up ICU. Partitions created makeshift private rooms; fans and vents filtered the air to prevent pathogens from escaping. In tents outside the hospital, fever and cough clinics allowed low-risk patients to seek treatment without risking exposure in the ED. “There were points when we were stretched thin, but at least our plan made for organized chaos,” says Romney.

By April 7, as many as 85 percent of the Allen’s beds were occupied by Covid-19 patients. Romney’s team helped facilitate family video chats and frequently checked in with those infected to remind them they weren’t alone. Romney herself dove into 12-hour shifts, checking oxygen-tank levels, coordinating shift changes, and quickly directing the newly admitted to their bed assignments—all to keep patients moving through the ED to make room for new ones.

In mid-April, the Allen’s ED staff learned that, for the first time in weeks, discharges outnumbered admissions. That energized Romney—as did witnessing her colleagues, New Yorkers, and people all over the world banding together. “For better or worse, our actions impact one another, as a local and global community,” she says. “That’s a fundamental lesson that I hope will translate beyond this crisis.” — A R I E L D I XO N

“We had to keep thinking one step ahead. If we had approached this like it was any other day in our emergenc y depar tment, it would have been chaotic.”

—MARIE-LAURE D. ROMNEY

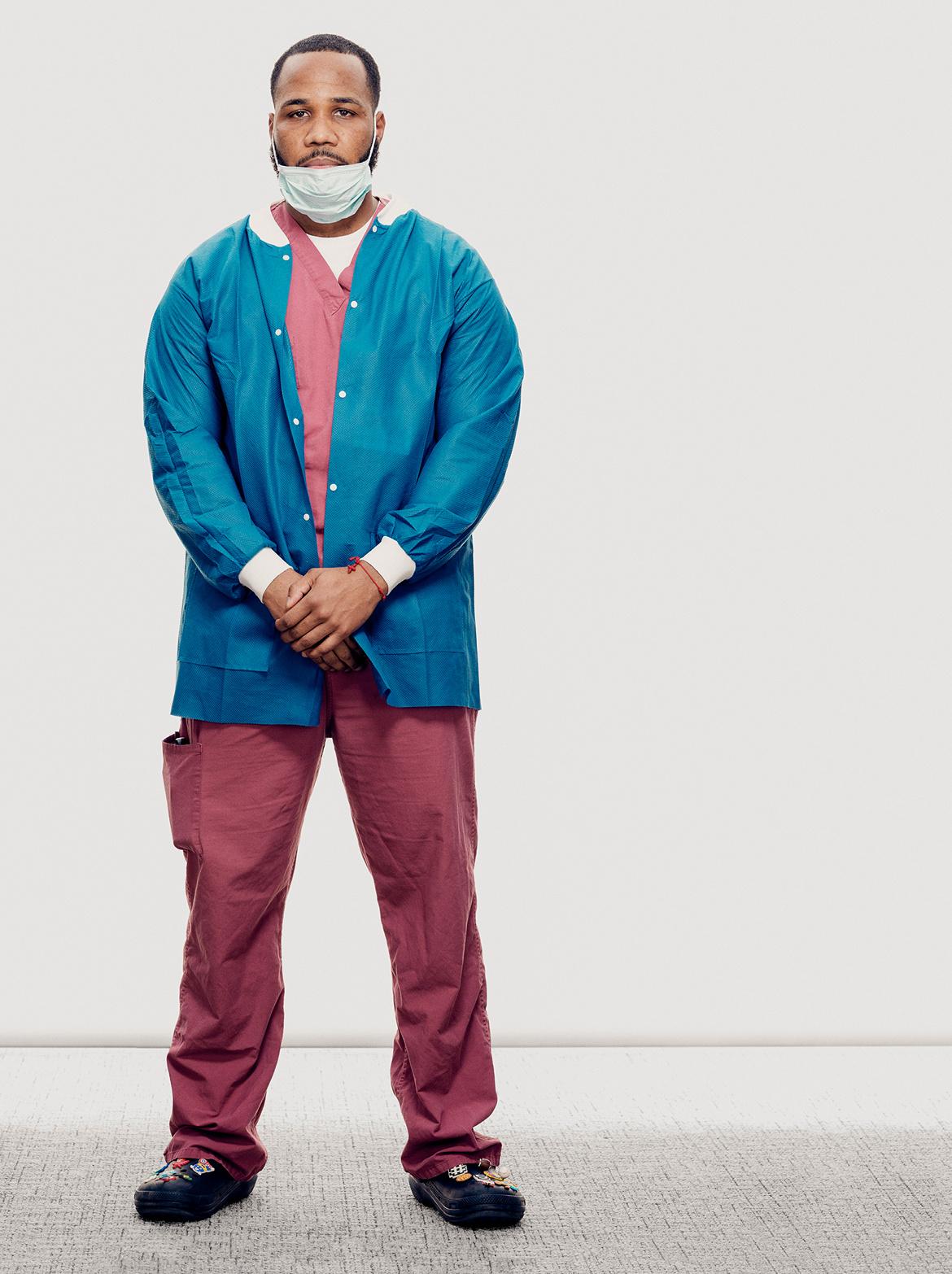

EUGENIO MESA

ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES WORKER NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital

About 25 times a day, 28-year-old Eugenio Mesa walked into a Covid-19 patient’s room wearing a blue disposable cap, goggles, two face masks (one N95, the other surgical), purple rubber gloves, and a full-length yellow surgical gown over his red scrubs. His black Crocs— decorated with a bluebird, a pizza, a red electric guitar, and other colorful charms—were encased in blue booties.

As quietly as possible, Mesa wiped down every surface with disinfectant and mopped the floor; sweat trickled down his back, and his goggles fogged up. Knowing he couldn’t touch his goggles or face, he focused on his breathing and his methodical work. Before leaving, Mesa lifted medical waste from its bin, taking care to ensure nothing spilled, and double bagged it. “I stayed calm by reminding myself that as long as I was protected and doing the job correctly, I had nothing to fear,” he says.

Mesa had been housekeeping at the hospital for a little over a year when his supervisor pulled him aside in early March and asked whether he would clean the rooms of Covid-19 patients—a job many people would be unwilling to do out of fear for their (and their loved ones’) lives. But Mesa didn’t hesitate: “Yes, I can do it.” He soon found himself working seven days a week, sometimes 16-hour shifts, with a team of four other housekeepers. “This is about helping out and making sure we fight this as a unit, all together,” he says. “The few of us who go inside these rooms—we’re brave.” Mesa and his colleagues worked two to a cart, switching off between cleaning and managing the supplies. A fifth housekeeper continually ran to the basement to replenish the stock of disinfectant, garbage bags, and other necessities.

As an athlete who played baseball at Sullivan County Community College and still participates in several softball leagues in Manhattan and the Bronx, Mesa was in good shape for the physically demanding role; his competitor’s mindset helped him stick with his grueling new schedule. When he’d leave the hospital after his shift, he’d often work out, eat, and go straight to bed. “I had to make sure I stayed strong so I could wake up the next day and do the same thing again,” says Mesa, who feels an obligation not just to the patients but to his fellow caregivers. “Working nonstop is stressful, but I also feel good about contributing to the cause. Making sure those rooms are clean and organized makes it easier for the doctors and nurses to do their jobs— and help people get better.” — M A R Y PAU L I N E LO W R Y

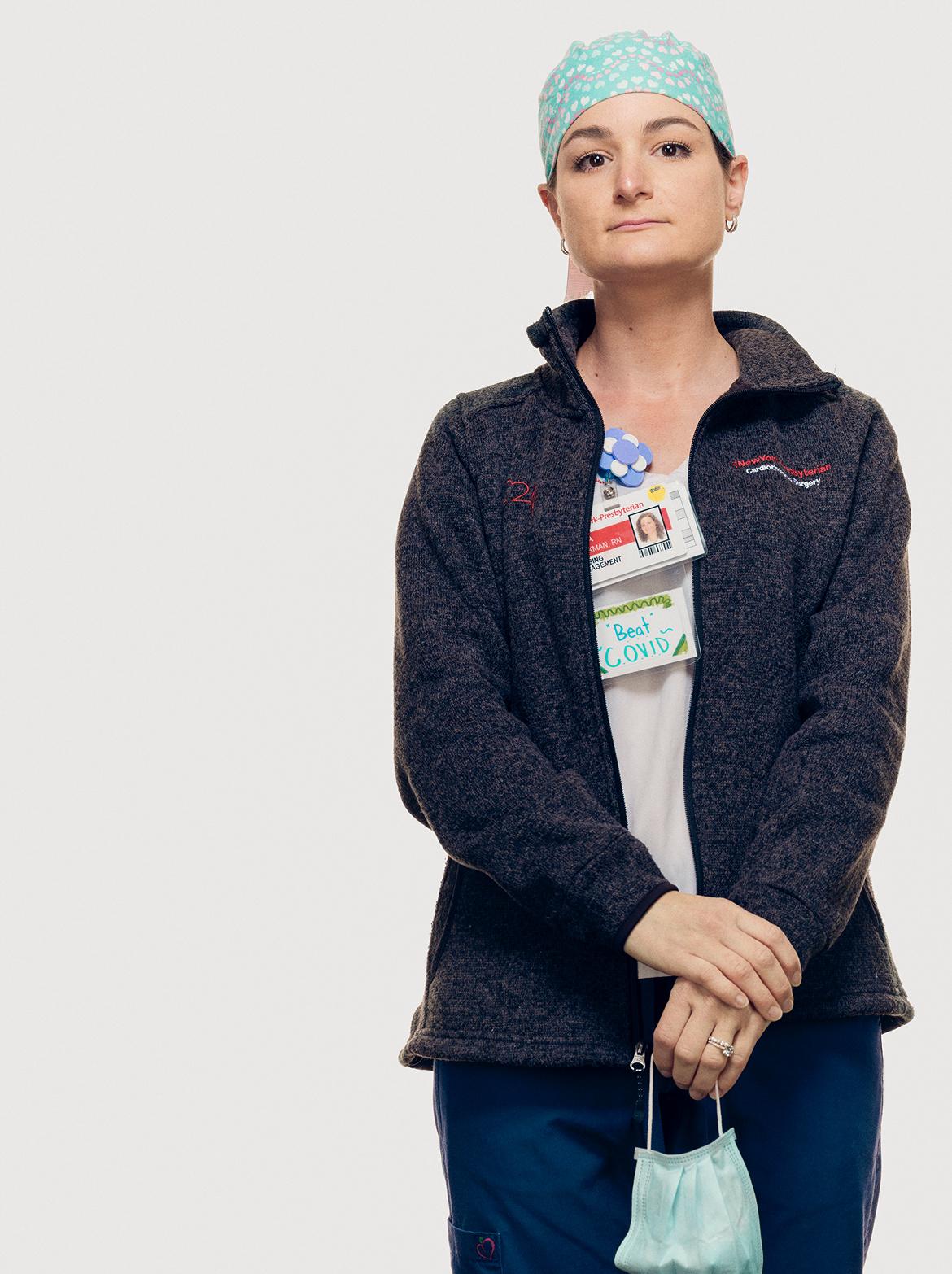

DIANA BRICKMAN

C R I T I CA L CA R E N U R S E NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

Like every healthcare worker in New York in mid-March, Diana Brickman knew the coronavirus was bearing down on the city. But she had no idea why she, a program coordinator in NewYork-Presbyterian’s cardiac unit, had been summoned to the small conference room that was serving as the hospital’s Covid-19 command center.

Her boss’s boss, the chief cardiac nursing officer, got straight to the point: Could Brickman train the hospital’s nurses to treat the tsunami of Covid-19 patients headed to the ICU—and by yesterday? The ask felt surreal. True, for the past two years Brickman’s job had been to educate and assess the hospital’s cardiac nurses, but training an army of caregivers from a half dozen specialties for potentially deadly work for which there were barely established protocols? “Luckily,” she says, “there wasn’t time to be nervous.”

On-boarding a new ICU nurse normally takes about three months— and those caregivers have often already spent a few years preparing specifically to treat patients in critical condition. Now nurses certified in anesthesia, pediatrics, and operating-room care were being tasked with the job. Their new patients would be the sickest of the sick, dependent on catheters, feeding tubes, and multiple intravenous lines. Each bed in the ICU is surrounded by a phalanx of machines measuring temperature, blood pressure, pulse, and respiration rate. “You’ve got to interpret what all the numbers mean and anticipate what the patient is going to need next,” Brickman says. “It can be overwhelming.” Even more daunting, the nurses would be required to monitor a ventilator, a necessity for most Covid-19 patients in critical condition. “People with breathing tubes can’t talk or cough, so you have to know what signs to look for if they need suction or can’t tolerate the airflow.”

For four days, Brickman and a team of eight colleagues worked nonstop, at the hospital and at home, to streamline a curriculum from a 12-week process into a laser-focused, three-hour prep course. Then they put their plan in motion, converting three hospital conference rooms into classrooms, each dedicated to a specific topic. The trainees arrived in batches—30 in the morning, 30 in the afternoon—according to their specialty so that the instruction could be tailored to their particular knowledge gaps; an operating room nurse, for example, would need more ventilator training than a nurse anesthetist would. The lessons were both general (how to handle common ICU medications) and specific to Covid-19 (how to minimize the chance of exposing yourself to the virus while inserting and removing a breathing tube). In just ten days, Brickman’s task force transformed 413 nurses from throughout the hospital into critical care specialists.

As the surge of coronavirus cases inundated the ICU, the team Brickman helped assemble rose to the challenge, and as the number of discharges ticked up and New York City’s curve started to flatten, she eventually saw reason to be hopeful. “I’m optimistic that many of our patients will continue to get well,” Brickman says, “and that someday soon, there will be an end to this disease.” — C A T H E R I N E G U T H R I E

Photography and initial reporting by Benedict Evans and his assistant, Marion Grand, on behalf of Hearst Magazines.