5 minute read

THE N EW NATU RAL

the new natural

In yards around the country, there’s a gardening movement that aims to work with nature instead of against it.

Advertisement

IT USED TO BE SIMPLE. To plant a “natural” garden, you banished strict geometry from the design and stuck to native plants. Today, though, the term is taking on a new meaning with a relaxed style that’s right at home in the typically more cultivated areas of the landscape (for example, the front yard). Four ecologically minded designers in particular are helping define the naturalistic garden in achievable ways for home gardeners.

Larry Weaner, a Pennsylvaniabased landscape architect with whom I coauthored the book Garden Revolution: How Our Landscapes Can Be a Source of Environmental Change, earned his reputation creating meadow and woodland plantings, but he understands the desire of many of his clients for more domesticated plantings, particularly in the areas immediately around their houses. Native plants, especially newer cultivated types (“nativars”), function well in such settings while still providing benefits to wildlife and pollinators. Why opt for Asian rhododendrons, Weaner says, when you can choose native azaleas that bloom from April to September and provide colorful fall foliage, too?

This new movement is still in the process of finding an ideological balance. Formerly, natural gardeners insisted on the sole use of only unhybridized native species. To include anything else was to doubt the gardener’s credibility as an environmentalist. But in a world where humanity’s fingerprints are almost everywhere, does it make sense to return

NATURAL BUT NOT STRICTLY NATIVE

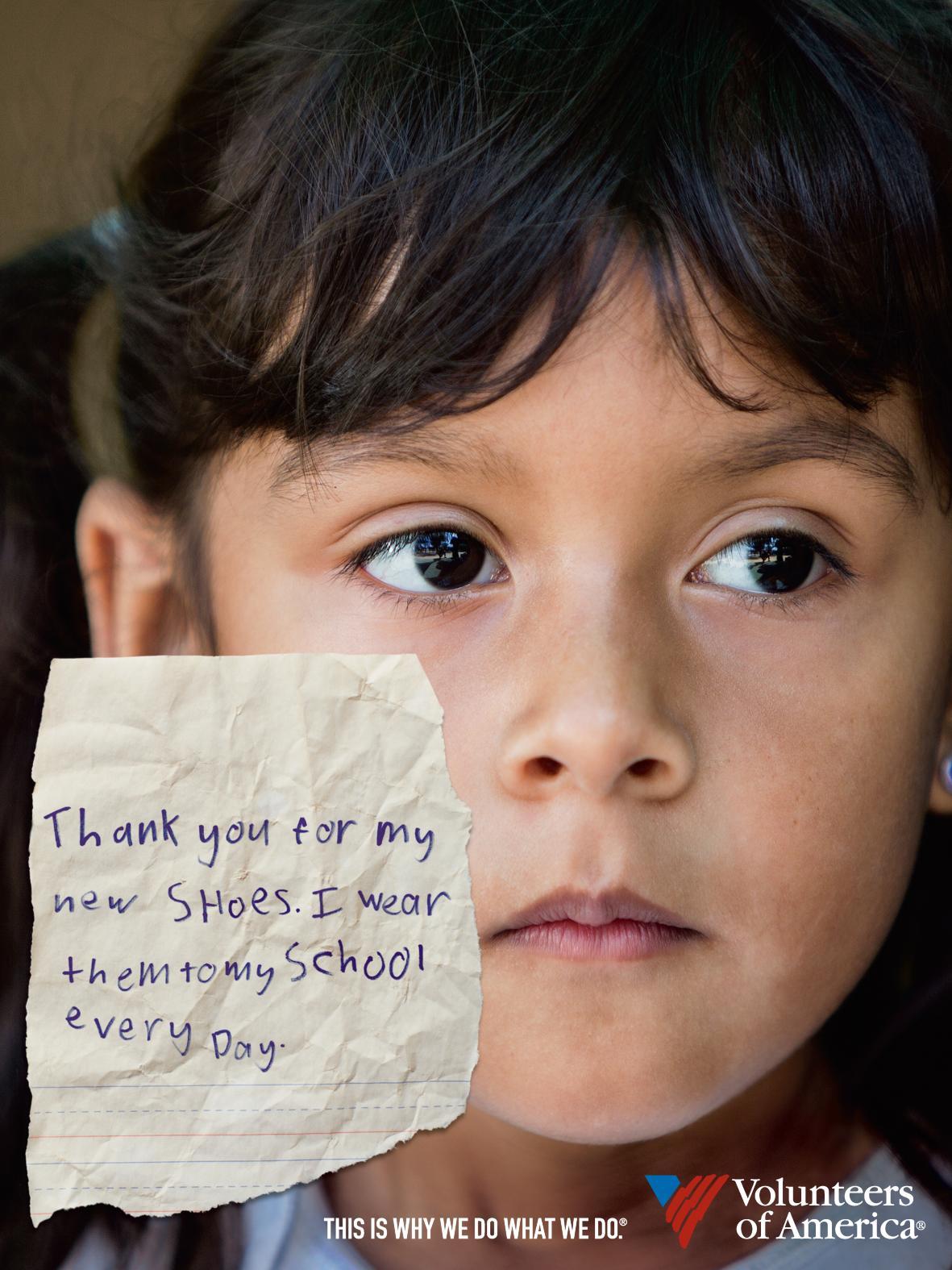

Mexican feather grass (Nassella tenuissima), Nepeta ‘Walker’s Low’, ‘Caradonna’ salvia, and ‘Purple Sensation’ allium mingle in the streetside border of Thomas Rainer’s Washington, D.C., home. (Caution: Nassella can be aggressive in some areas. Search invasivespeciesinfo.gov for your region.)

GARDENS OF ANY STYLE CAN BENEFIT FROM APPLYING NATURAL PRINCIPLES. —THOMAS RAINER

the home landscape to the wild? Thomas Rainer, a landscape architect based in Washington, D.C., thinks not, at least in most cases. Rainer says gardeners should move beyond the geographical origin of plants and focus more on whether a garden or landscape functions like a natural ecosystem. To accomplish this, Rainer designs plant communities, assemblages of compatible plants that are layered similar to their natural prototypes. A woodland garden, for example, should include a canopy layer of trees, a layer of smaller trees and woody shrubs, and an herbaceous layer of perennials and annuals that carpets the ground.

Where ordinary turf was once the rule, plants thrive in loose layers inspired by how the various species grow in nature.

September 2016 | BHG 63

Trademarks owned by Société des Produits Nestlé S.A., Vevey, Switzerland

The blending of wild with domesticated plants is clearly demonstrated in the work of Adam Woodruff, an award-winning, M issouri-based designer with a degree in botany. He deliberately mixes formal elements into wild-inspired gardens, using the formal to enhance the lush free-and-easy aesthetic. By incorporating structural elements, such as clipped hedges or repeating a pattern of trees and shrubs, gardeners can create a sense of formality and tension—pattern against wild—which helps link a naturalistic garden to the suburban home, he says.

Designed plant communities reinsert nature into all sorts of places, even in urban areas where people might lose touch with the natural world. Margie Ruddick, a Philadelphia landscape architect who has brought the wild into the hearts of cities in public projects such as New York’s Q ueens Plaza, values indigenous plants and relies on them heavily in her designs. Yet she also likes to include culturally native species—plants that have become important to the people of the region and make them feel at home. She cannot imagine, for example, the eastern Long Island landscape of dunes and beaches without the omnipresent wild rugosa roses, even though the shrub originated in Japan. Gardens cannot exist without gardeners, and these new natural landscapes seek above all to reunite the two.

RECOMMENDED READING

Q GARDEN REVOLUTION Larry Weaner and Thomas Christopher (Timber Press, 2016)

Q PLANTING IN A POST-WILD WORLD Thomas Rainer and Claudia West (Timber Press, 2015)

A manicured lawn and evergreen balance this informal border.

GROUND RULES

Transform your yard with these natural gardening techniques.

MIMIC NATU RE

Observe where native plants succeed in your region and grow them in similar sites (soil and sunlight) in your garden.

TRY NATIVARS

Cultivated forms of natives can be more compact or offer a wider color range than the species.

C REATE CONTRAST

Add formal elements such as a topiary yew to punctuate an informal planting.

VOLUNTEERS

Welcome those stray seedlings that pop up in unexpected places. Just weed out any that you don’t want. Q

Go a little wild

Learn how to apply naturalistic design strategies to your garden or landscape. BHG.com/Natural

drawing from NATURE

Stylist and author Selina Lake shares strategies for adding botanical style to your rooms. No digging required.

HANG A PRINT FROM A CLAMP - STYLE WOODEN PANTS HANGER.

“ THERE’S N O such thing as too many plants,” says Selina Lake, a Londonbased interiors stylist, author of seven decorating books, and a master at blurring the line between indoors and out. In her newest book, Botanical Style, Selina shows how to use plants and nature motifs to green up and play up your personal style —from boho to industrial. “I love decorating with nature,” Selina says, “whether it’s wallpaper with a leafy design, fabric with a floral pattern, or adding plants to a table.” For quick hits of nature, Selina uses botanical and entomology prints and illustrations. “Group them together or dot them around your space on mantels or shelves.” The best part? You don’t have to remember to water.

GREEN SCENES

Selina’s mantel, above, is home to a pink ‘Pennington Gem’ penstemon bound for the garden, cuttings, a cloche-covered Fittonia, and a dill and fern tray by Michael Angove. A potted Ginkgo biloba tree, right, plays houseplant before heading outdoors. The leaves look brilliant green against a black backdrop. Selina’s favorite black paint: Farrow & Ball’s Pitch Black.