3 minute read

Notes

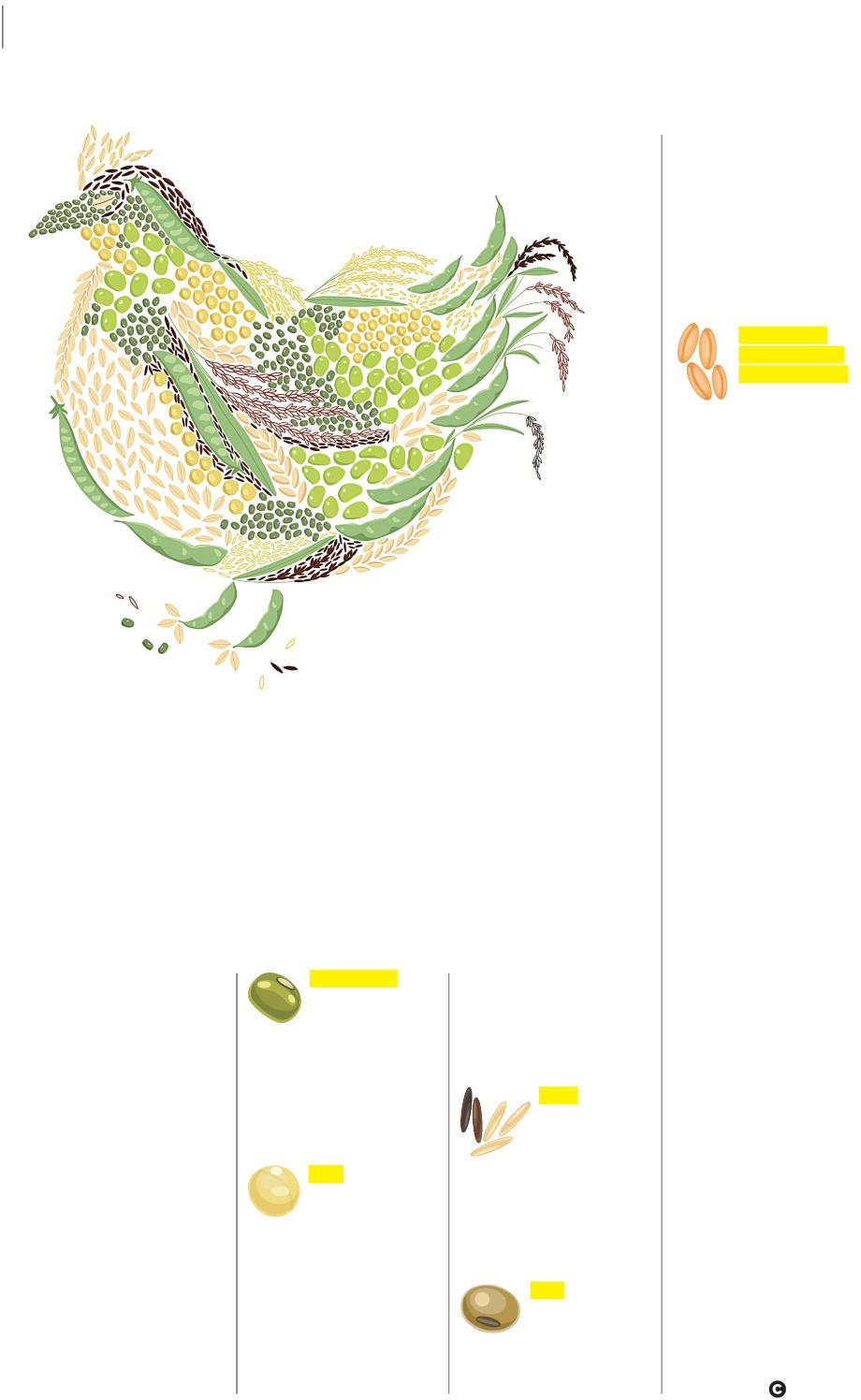

What’s really in your plant-based meat?

A guide to plant proteins and what they do

Advertisement

Written by EMILY KICHLER, RD Illustration by STEF WONG

FROM VEGAN CHICKEN to faux fish sticks, plantbased meat alternatives are popping up in grocery aisles and on chain restaurants ’ menus in record numbers—and they ’ re expected to make up a third of the market for protein products by 2024. Responding to massive consumer demand (nearly 40 percent of Canadians are incorporating more plant-based foods in their diets), companies are formulating tastier-than-ever burger patties, breaded nuggets and ground “ meats, ” often with qualities that mimic those of animal products surprisingly well. But where does the protein in these products come from, and what role does it play?

Proteins are made of nine essential amino acids, which must come from our diet. These amino acids combine to form “ complete ” proteins. Unlike animal sources, plant-based ones are often low in one or more amino acids, making them incomplete. Since each plant protein source contributes different properties and nutritional value, they ’ re often used in combination. Here ’ s a breakdown of the most popular plant-based sources.

Mung bean

Mung bean protein is typically included as part of a combination of plant proteins because it has excellent gelling qualities, which helps create the texture of meat alternatives.

Pea

Pea protein, one of the most common ingredients in plant-based products, is made from yellow peas that have been dried, ground and rinsed to remove the starch and fibre so that only the protein remains. Compared to protein isolated from other plant sources, it’ s more easily digestible and contains a more complete profile of essential amino acids. One downside? It can have a pronounced pealike taste.

Rice

Rice protein is most often used in combination with pea protein because it’ s high in methionine, the amino acid that pea protein is low in. Together, they form a complete protein.

Soy

Originating from soybeans, soy protein has a neutral flavour and is unique because it contains all of the essential amino acids, making it a complete protein on its own. Soy is also high in isoflavones, which may offer protection from some cancers. One caveat: Soy allergies are relatively common, which takes this option off the table for many people.

Vital wheat gluten/wheat protein isolate

Unsurprisingly, both vital wheat gluten and wheat protein isolate come from wheat.

When wheat flour is hydrated, the gluten (a type of protein) becomes activated. This hydrated mix is then processed to remove everything but the gluten, which is dried and ground into a powder. The main difference between vital wheat gluten and wheat protein isolate is the concentration of protein—the latter contains more of it.

Vital wheat gluten, the primary ingredient in seitan, is chewy and slightly rubbery, which helps it mimic the texture of meat.

Neither option works if you have gluten intolerance or celiac disease, however.

WHILE THEY MAY be healthier than actual meat, many plant-based meat alternatives don ’t automatically deserve the “health halo ” they often receive. Highly processed plant proteins also tend to contain additives (such as texturizers, dyes and emulsifiers) and can contain a large amount of sodium. They ’ re often made with palm or coconut oil, so they can be high in saturated fat, too.

Just as a whole chicken breast is better for you than chicken nuggets, minimally processed sources of plant protein (think beans, lentils, chickpeas, tofu, nuts and seeds) are a more nutritious choice than many plant-based meat alternative products.