21 minute read

Health News

students with disabilities represent 18.5 percent of students with disabilities under the Individual With Disabilities Education Act, but they make up 29 percent of students with disabilities referred to law enforcement and 35 percent of students with disabilities subjected to school-based arrest.

Effects of Systemic Racism

Advertisement

When Black parents try to enlist help for their children, medical professionals often don’t take their concerns seriously—a form of implicit bias that can play a significant role in medical outcomes for Black people in genera l. When researchers at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine evaluated more than 9,000 notes in the medical records of one clinic, they found that doctors were more likely to use judgmental words that suggested skepticism (such as “claims” and “insists”) for Black patients than for white patients, and that Black patients were more likely to receive lower quality of care.

When it comes to developmental delays, a pediatrician may dominate the conversation and ask Black parents fewer questions, Dr. Spinks-Franklin says, even when their child is at high risk. “Simply asking parents what their expectations are about normal development would give them the opportunity to voice their concerns and discuss issues that need to be addressed,” Dr. Spinks-Franklin says.

Breanna Major, a social worker in Aurora, Colorado, and mother of an 8-year-old daughter on the spectrum, says that her family’s experience was a clear case of implicit bias and racism. Major always suspected something was different about her daughter from infancy and started trying to get help for her at age 2, but she didn’t receive an autism diagnosis until her daughter was 6. After being bounced around to different agencies by her health-care provider, she was unable to convince anyone her daughter might have autism. Instead, she faced questions about her own aptitude and was directed to programs to improve her parenting skills. “They made it seem like it was my fault and even asked culturally insensitive things such as how often I washed my daughter’s hair,” Major says. During a visit to her own doctor, who is also Black, Major expressed her frustration about not being able to find help for her daughter. “My doctor said, ‘I think you’re being discriminated against because you’re a single Black mother,’ ” Major says.

“When I finally met with an evaluator at a children’s hospital, I was told that my daughter’s prior evaluations had been enough to get her a diagnosis, and it wouldn’t have been a problem if I were white,” Major says. She says she’s filed an official complaint and shared her story with a regional administrator to address concerns regarding bias and providers’ cultural competency.

Not only is there cause for Black people to be wary of the medical establishment, but kids with autism have behavioral issues that legitimately make parents uncomfortable about how they will be viewed in health-care settings, says researcher Emily Feinberg, Sc.D., a clinical nurse-practitioner and associate professor of pediatrics at Boston University School of Medicine. A child might bolt from their parents, for example, or struggle with clothing textures due to sensory issues.

That was a feeling Major was very familiar with when attempting to get a diagnosis for her daughter. “At each appointment during the evaluation process, I made sure we were both well-dressed and her hair was combed well,” Major says. “I didn’t want to give them any reason to suspect that I was a negligent parent.” In fact, a study by Dr. Feinberg and her team found that Black mothers worry that discussing their own mental health challenges could trigger the involvement of child protective services—findings that suggest similar fears could also be a barrier to discussing concerns about their child’s development.

WHEN FAMILY AND FRIENDS QUESTION YOUR CONCERNS

If you find yourself on the defensive when you share worries about your child’s development, Dr. Adiaha Spinks-Franklin suggests these responses:

“Children with speech delays are more likely to struggle with learning how to read and make friends. I don’t want my child to have those problems, so I am going to talk to the pediatrician about getting help for them.”

“I would rather be safe than sorry. I am worried about my child’s development, so the wise thing for me to do is to ask the doctor to help us find the support they need, so they can be as successful as possible in life.”

“I know that Uncle Jerry was a very late talker and that he had a hard time in school. He didn’t have access to the kinds of help and resources that we have today. We don’t want our child to struggle more than they have to when there are many ways to help them while they’re young.”

“When we know better, we do better. We didn’t wear seat belts in the 1970s, but now we do. They used to use lead paint until we learned it wasn’t safe. Now we know that developmental delays can be a sign that something is seriously wrong, and we have resources to help children.”

A Sense of Stigma Among Friends and Family

Compounding the problems parents often face in health-care settings are ones they can experience closer to home. Not all parents know what the signs of autism and other developmental

disorders look like, Dr. Feinberg says. A study in Pediatrics found that Black mothers were more likely to consider their child to be “just different and developing on their own time” rather than developmentally delayed.

However, parents like Gulley , who do have concerns, may delay seeking help out of fear of being judged by family and friends, Dr. Brewer notes. When a child has behavioral issues associated with autism—such as not responding to their name, having a limited vocabulary, losing previously learned skills, and having meltdowns—some Black parents say it’s common to hear skeptical remarks from elders and peers. “When people see my son behaving a certain way, they make comments—like I’m not disciplining him enough or that I’m using some kind of new-age parenting style,” Gulley says. “In my community, people love using social media to call out another Black mom who let her son yell and have a tantrum in the store.”

It can be understandably hard for parents to address worries about their child when they get conf licting information from family and friends who believe there’s a stigma associated with autism and disability, says Davis-Pierre. Kenya Eaton, a mother of four in San Dimas, California, didn’t receive an autism diagnosis for her son until he was 3, even though she’d raised concerns with their pediatrician when he was 18 months. Not only did she get pushback from relatives about her suspicions, but even her husband gave a contradictory account of her son’s behavior to the pediatrician, making it more difficult for Eaton to get a referral for an evaluation.

And those messages should ideally be delivered by trusted sources. A history of medica l discrimination can ma ke it hard for some Black families to accept information conveyed by a source they believe to be untrustworthy, Dr. Spinks-Franklin notes, and accepting advice that one’s child would benefit from special services can be more difficult when it comes from someone

who doesn’t look like you. Yet currently only 4 percent of speech-language pathologists are Black, 3 percent of occupationa l therapists identify as non-white, and less than 10 percent of developmental pediatricians identify as a minority.

Sending the Right Health Messages

Eliminating racial disparities in the medical system is a tall order, one that requires systemic changes. But there are some concrete ways to help make sure that all children get the diagnosis and treatment they need. For starters, public-hea lth campaigns about developmental milestones and delays should target people of color in a way that makes them feel seen, Dr. SpinksFranklin says. “Posters in pediatricians’ offices need to represent every community they serve. You can’t have a picture of a blond-haired, blue-eyed girl with autism and expect Black and brown people to think it applies to their kids too.” Initiatives similar to those waged to educate communities about COVID-19 and vaccination could also be beneficial when it comes to autism and other developmental delays, Dr. Brewer notes. That may mean health experts visiting churches, traveling to underserved communities, and hosting events after hours to accommodate varied work schedules. “The more we’re able to provide access to different services—whether it ’s hea lth fairs, drives at libraries, or evaluations at day cares and schools—the more we can improve health equity,” Dr. Brewer says. Creating safe spaces for Black families within health-care settings will go a long way toward reversing feelings of always being judged, Davis-Pierre says. And the more everyone learns about autism and delays, the more parents will be supported (not blamed) by their peers, their village, and society—and the sooner more children on the spectrum will have the opportunities they deserve.

Special Report

Hover your phone’s camera over the smart code to read “The Children Left Behind,” a Parents digital spotlight on the inequities in our education system.

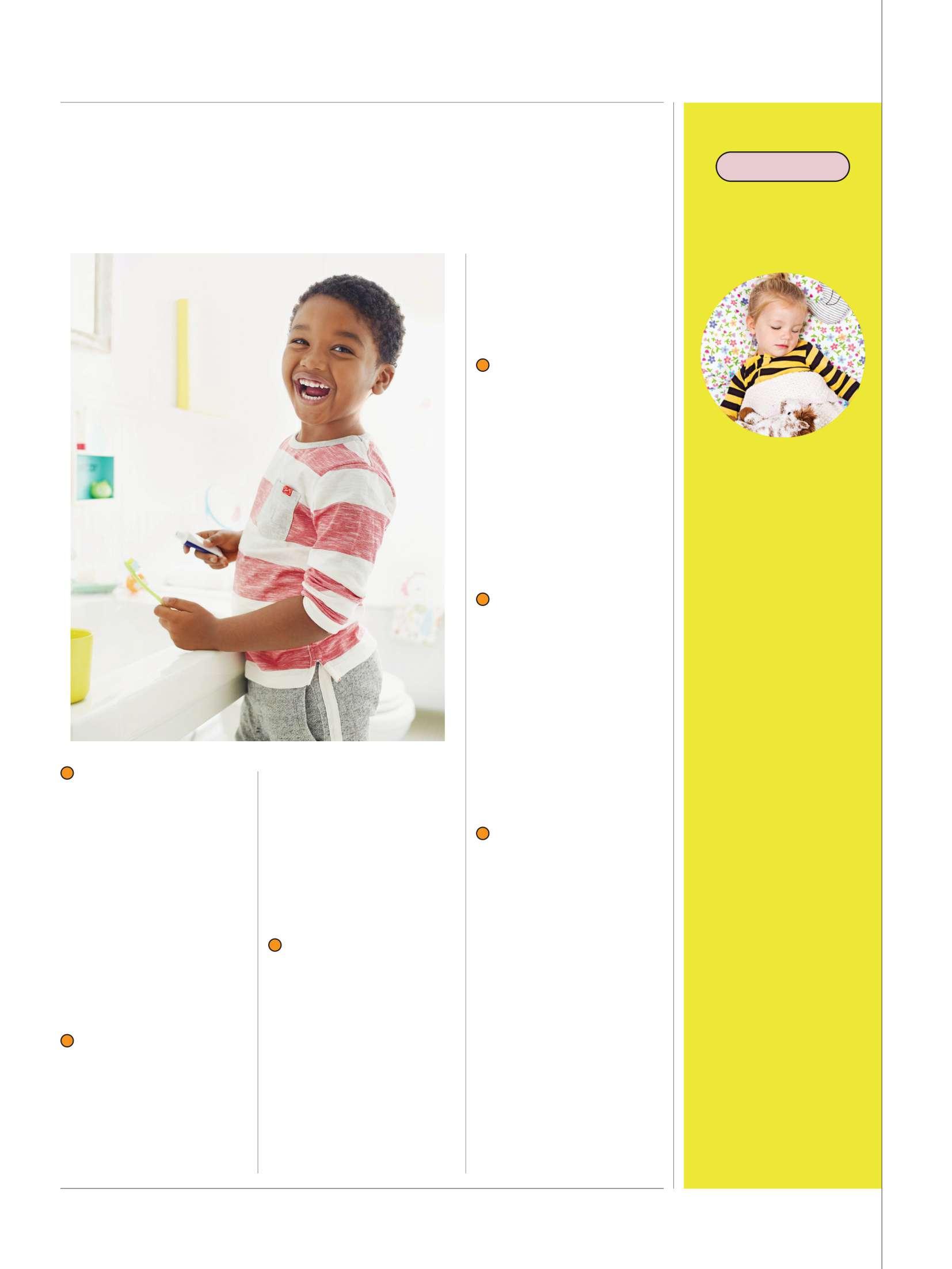

Spa rk l i ng K id Te eth , M i nu s the B at tle

If your child is a speedy brusher, prone to clamping down when you try to get in there, or too young to brush on their own (start when their teeth come in!), these tips from pediatric dentists can help take the stress out of sink time.

K E E P I T F U N It helps when parents create little challenges to encourage brushing, says Grace Yum, D.D.S., a board- certified pediatric dentist in Newport Beach, California. “If your toddler ate dinosaur chicken nuggets, say, ‘I see dinos in your mouth! We have to get them out!’ ” Or, she says, try a game of “You brush my teeth, and then I’ll brush yours.” Using a brushing app or singing a song while they brush can also keep the time from feeling like a drag.

F I N D F AV E F L AV E S “Try different flavors until you find the one your children like,” says Jeannie Beauchamp, D.D.S., president of the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry and a pediatric dentist in Clarksville, Tennessee. Let their taste buds guide the way, whether that means strawberry, bubble gum, or plain old mint. Remember to use a small amount and get a child-specific one, which will have the right fluoride content. Look for the American Dental Association Seal of Acceptance, and steer clear of whitening toothpaste, which can be too abrasive on young teeth.

L E T T H E M P I C K Give them a say in their brush too. A sense of ownership goes a long way, and a brush with their favorite character on it can be fun. An electric toothbrush with soft bristles and a small head is an especially good option: The vibrations break up food debris without requiring a child to use the proper pressure or have the dexterity that a manual toothbrush calls for. “It also helps you,” Dr. Yum says. “If you have a toddler, you probably have about 20 seconds to get in and out.” Dr. Yum suggests stocking up. Keep toothbrushes in every bathroom and in the kitchen so your kids can brush whenever inspiration strikes.

G E T T H E S TA N C E Your instinct might be to face your child while brushing their teeth, but it can be easier to stand behind them, says Dr. Beauchamp. This way, you can tilt your kid’s head back slightly and lean over with the brush. Dr. Yum suggests switching your usual grip when brushing someone else’s teeth. “Holding it like a pen is easier, because then you have a lot of wrist rotation.”

G O F O R T R I C K Y S P O T S

“Whatever dominant hand your child has, they will brush the opposite side of their mouth first, so that side is much cleaner,” Dr. Yum says. Offer to take a second pass and focus on their dominant side, which they probably skimped on. And while you’re choosing sides, be sure the back teeth are getting special attention. The chewing surface of molars has grooves where bits of food can stick.

S P L I T U P F O R S U C C E S S

When parents say brushing has really become a battle, Dr. Beauchamp suggests brushing their child’s bottom teeth in the morning and the top at night. “That way, at least once a day, all of them get brushed.” And if you absolutely must choose one time, prioritize nighttime brushing. You don’t want their meals from the day sitting on their teeth overnight. Dr. Yum explains that during the day, saliva acts as a natural buffer against cavities. “When you’re sleeping, saliva is not flowing, so your mouth becomes an acidic environment that is a feeding ground for bacteria,” she says. This means that before a nap is also a great time to brush.

P A G I N G D R . M O M

The good news is that most kids don’t hurt themselves while sleepwalking. But it’s worth being on heightened alert for the first third of the night, when sleepwalking is most common, and around life events such as travel and illness, which can disrupt sleep and trigger episodes.

Be sure to lock windows and doors and install gates by stairs. You shouldn’t need complicated locks since most people don’t do complex tasks while sleepwalking. You can also put an alarm or a bell on their door so you can hear if they’ve left their room.

Keep the area near their bed and their walking paths clear of tripping hazards. If episodes occur frequently, leaving a dim light on will help you and your child make it to and from bed safely.

You’ve probably heard this before, but unless your child is in danger, try not to wake them. Instead, if you see them, gently guide them back to bed. If they wake, know that they will be disoriented. They likely won’t remember sleepwalking, but they will remember waking up to your scared face. Do your best to remain calm so that they can too.

Source: Parents advisor Maida Chen, M.D., director of the Pediatric Sleep Disorders Center and a pediatric pulmonologist at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

IMPORTANT FACTS

This is only a brief summary of important information about PALFORZIA and does not replace talking to your healthcare provider about your condition and treatment. For complete product information, please see full Prescribing Information, including Medication Guide, at www.PALFORZIA.com.

WHAT IS THE MOST IMPORTANT INFORMATION I SHOULD KNOW ABOUT PALFORZIA? PALFORZIA can cause severe allergic reactions called anaphylaxis that may be life-threatening.

• You will receive your first dose in a healthcare setting under the observation of trained healthcare staff. • You will receive the first dose of all dose increases in a healthcare setting. • In the healthcare setting, you will be observed for at least 1 hour for signs and symptoms of a severe allergic reaction. • If you have a severe reaction during treatment, you will need to receive an injection of epinephrine immediately and get emergency medical help right away. • You will return to the healthcare setting for any trouble tolerating your home doses. Stop taking PALFORZIA and get emergency medical treatment right away if you have any of the following symptoms after taking PALFORZIA: Trouble breathing or wheezing; Chest discomfort or tightness; Throat tightness; Trouble swallowing or speaking; Swelling of your face, lips, eyes, or tongue; Dizziness or fainting; Severe stomach cramps or pain, vomiting, or diarrhea; Hives (itchy, raised bumps on skin); Severe flushing of the skin. For home administration of PALFORZIA, your doctor will prescribe injectable epinephrine, a medicine you must inject if you have a severe allergic reaction after taking PALFORZIA. Your doctor will train and instruct you on the proper use of injectable epinephrine. Talk to your doctor and read the epinephrine patient information if you have any questions about the use of injectable epinephrine. PALFORZIA is only available through a restricted program called the PALFORZIA Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) Program. Before you can receive PALFORZIA, you must: • Enroll in this program. • Receive education about the risk of a severe allergic reaction (anaphylaxis) by a healthcare provider who practices in a setting that is certified through the REMS program. • Understand that you will be monitored in a healthcare setting during and after the Initial Dose Escalation and for the first dose of each Up-Dosing level. • Receive education about how to maintain a peanut-free diet. You must attest that you will continue to avoid peanuts at all times. • Fill the prescription your healthcare provider gives you for the injectable epinephrine. You must attest that epinephrine will be available to you at all times. Talk to your healthcare provider for more information about the PALFORZIA REMS program and how to enroll.

WHAT IS PALFORZIA?

PALFORZIA is a prescription medicine derived from peanuts. It is a treatment for people who are allergic to peanuts. PALFORZIA can help reduce the severity of allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis, that may occur with accidental exposure to peanut. PALFORZIA may be started in patients aged 4 through 17 years old. If you turn 18 years of age while on PALFORZIA treatment you should continue taking PALFORZIA unless otherwise instructed by your doctor. PALFORZIA does NOT treat allergic reactions and should not be given during an allergic reaction. You must maintain a strict peanut-free diet while taking PALFORZIA.

WHO SHOULD NOT TAKE PALFORZIA?

You should NOT take PALFORZIA if: • You have uncontrolled asthma. • You ever had eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) or other eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease.

WHAT SHOULD I TELL MY DOCTOR BEFORE TAKING PALFORZIA?

Tell your doctor if you are not feeling well prior to starting treatment with PALFORZIA. Your doctor may decide to delay treatment until you are feeling better. Also tell your doctor about any medical conditions you have. You should tell your doctor if you are taking or have recently taken any other medicines, including medicines obtained without a prescription and herbal supplements. Keep a list of them and show it to your doctor and pharmacist each time you get a new supply of PALFORZIA. Tell your doctor if you are pregnant, planning to become pregnant, or breastfeeding. Your doctor may decide that PALFORZIA is not the best treatment if: • You are unwilling or unable to receive (or self-administer) injectable epinephrine. • You have a condition or are taking a medication that reduces the ability to survive a severe allergic reaction.

WHAT ARE THE POSSIBLE SIDE EFFECTS OF PALFORZIA?

The most commonly reported side effects were: stomach pain, vomiting, feeling sick, itching or burning in the mouth, throat irritation, cough, runny nose, sneezing, throat tightness, wheezing, shortness of breath, itchy skin, hives, and/or itchy ears. PALFORZIA can cause severe allergic reactions that may be life-threatening. Symptoms of allergic reactions to PALFORZIA can include: Trouble breathing or wheezing; Chest discomfort or tightness; Throat tightness or swelling; Trouble swallowing or speaking; Swelling of your face, lips, eyes, or tongue; Dizziness or fainting; Severe stomach cramps or pain, vomiting, or diarrhea; Skin rash, itching, or raised bumps on skin; Severe flushing of the skin. PALFORZIA can cause stomach or gut symptoms including inflammation of the esophagus (called eosinophilic esophagitis). Symptoms of eosinophilic esophagitis can include: Trouble swallowing; Food stuck in throat; Burning in chest, mouth, or throat; Vomiting; Regurgitation of undigested food; Feeling sick. For additional information on the possible side effects of PALFORZIA, talk with your doctor or pharmacist. You may report side effects to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.T/medwatch.

N E W S T O S M I L E A B O U T

1

Charitable giving has increased. More than 90 percent of Americans say it is more important to support charities now versus before the pandemic, according to a report released by the cleft-focused charity Smile Train. Around 30 percent of those surveyed say their donations have increased, and 44 percent pick groups that help children.

2

Movement boosts vocab. Exercise may help a child’s vocabulary grow, shows research from the University of Delaware. School-age children were taught new words and then asked to do various tasks. Those asked to swim then did 13 percent better when tested on the vocab, while others showed no change.

3

Empathy lessons have additional bene�its. Teaching students to empathize with others improves their creativity, says a study from the University of Cambridge. Students ages 13 to 14 were taught to solve problems by considering other people’s perspectives. They then scored 78 percent higher on creativity tests than other students and displayed more “emotional expressiveness” and “open-mindedness.”

H o w t o Ta l k t o Yo u r K i d s A b o u t S t ay i n g H e a l t h y

Nina Shapiro, M.D., is on a mission to get kids to take good care of themselves. In her new book, The Ultimate Kids’ Guide to Being Super Healthy, using language that children ages 6 to 10 can relate to, she explains how the body works. Here’s how to answer your kid’s tricky questions.

“Why can’t I stay up later?”

I know that when we say it’s time for bed, you’d rather be doing something else instead, but did you know that sleeping isn’t “doing nothing”? So much happens inside your body during the night. It produces a substance called growth hormone that helps you get taller and stronger. Your body then goes through five stages of sleep that help your brain rest and store information that you learn during the day. Pretty cool! The stage when you dream is called REM sleep, or rapid eye movement sleep. Your eyes move back and forth super-quickly even though they’re closed. It’s so fast that you can’t even move them that fast when you’re awake. Plus, you did so much today! If you want to play tomorrow, your body needs a time to rest. Your breathing and heart both get to slow down overnight so you will have more energy to run around.

“Why can’t we have cookies (or cake or candy or ice cream) for dinner?”

I know you love sweets. I do too! And it’s okay to have them sometimes, but you can’t have them for dinner because you need to leave the most room in your tummy for nutritious foods. Sometimes sweets have healthy ingredients, but they are usually missing important things that help us grow and give us long-lasting energy. Proteins like the chicken, eggs, or soy on your plate give you strong energy, and the vegetables like broccoli, carrots, or peas on the side have vitamins that do all sorts of important jobs in your body, such as help you grow, have energy to play sports, and even focus at school. They also have fiber. Fiber helps move all the food you eat through your stomach, it slows things down in your body, and it helps you poop easily and regularly! You know what? There are recipes for cookies that have some of these healthy things too—let’s pick one to make for dessert.

“What’s the big deal about screen time?”

Just like cookies, I enjoy screen time too! But spending too much time looking at a screen can cause you to lose track of time and get impatient. It’s easy to get pulled into an exciting, high-speed game or group chat. But when you’re used to the speed of screen time, the real world can seem slow and make you frustrated when the click of a button doesn’t make things happen. Remember when we give you a time limit, and then it feels as if no time has passed? That’s because you get so focused on the screen that your brain is tricked into forgetting about the world around you. Plus, the light from the screen puts a strain on your eyes and makes it hard for your brain to switch to other things like playing or sleeping. Your screen is especially distracting at night. Let’s pick a family charging station where all the devices go at night. Grown-ups too!

Another Reason to Get the Flu Shot If your child gets

COVID-19, they’ll be less likely to suffer symptoms if they’ve had their flu shot this year. Researchers from the University of Missouri School of Medicine in Columbia reviewed more than 900 cases of children with COVID last year. Those who had received a flu shot had higher rates of asymptomatic cases (nearly 70 percent versus 61 percent). Through a phenomenon called viral interference, the inactivated virus in the flu vaccine increases the body’s resistance to a second virus, explains lead author Anjali Patwardhan, M.D. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has said the COVID vaccine and other vaccines can now be given within 14 days of each other .

1

The silliest thing T-Bone does is the boogie! It’s his happy dance after he eats.

2

I give T-Bone lots of kisses to take care of him.

A n ima l Hou se!

Naya, 6, and her German shorthaired pointer, T-Bone, 10, have each other’s back.

photograph by P R I S C I L L A G R A G G

3

We also have pet jellyfish, but T-Bone gets along with them.

4

T-Bone looks really cute when he begs for a treat.

5

If he had a superpower, it’d be throwing the ball by himself. Playing fetch is his favorite thing to do.