11 minute read

David and Linda Hurley

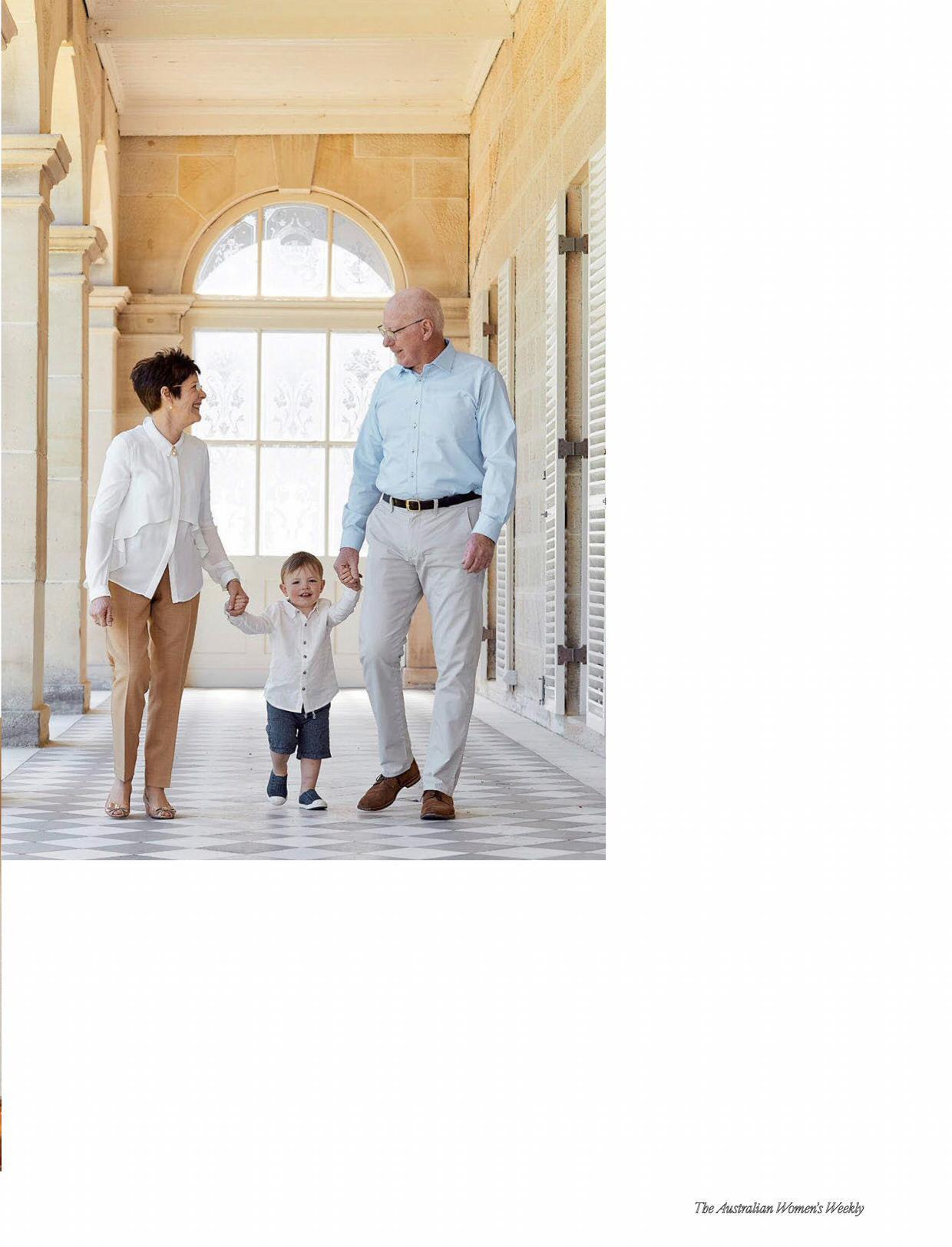

The Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia, His Excellency General the Honourable David Hurley AC DSC (Retd), dotes on his grandchildren, including two-year-old Charlie.

Advertisement

– Linda Hurley

The

Governor-General of Australia lifts two-year-old Charlie onto a chair so he can survey the many platters of cakes and biscuits laid out for afternoon tea on the dining table at Admiralty House. “Which are you going to choose?” the doting grandpa asks young Charlie, who hesitates, his eyes as wide as saucers. But then he grins and begins the painstaking task of choosing the best one. First he nibbles a lamington. Perhaps not; he passes the uneaten portion to grandpa, who finishes it off. A shortbread? A chocolate slice? Something that looks delicious with jam in the middle? Before long the Governor-General and Charlie have polished off at least half a dozen biscuits and are both looking pretty pleased with themselves. It brings to mind one of the Hurley family’s favourite children’s books, Possum Magic. If only there was a vegemite sandwich.

“I love Charlie. He’s such a character,” the proud grandfather tells The Weekly later that afternoon as we sit in his harbourside study, reflecting on an extraordinary year. “At the moment, I just enjoy watching him wander, to see what’s interesting in his life.” There’s reconstruction work underway at Admiralty House, down by the Sydney waterfront. “He sat down the other day and watched that digger for half an hour, and he talked about it. We didn’t see Charlie for four months during the lockdown and in that time, he developed a vocabulary.”

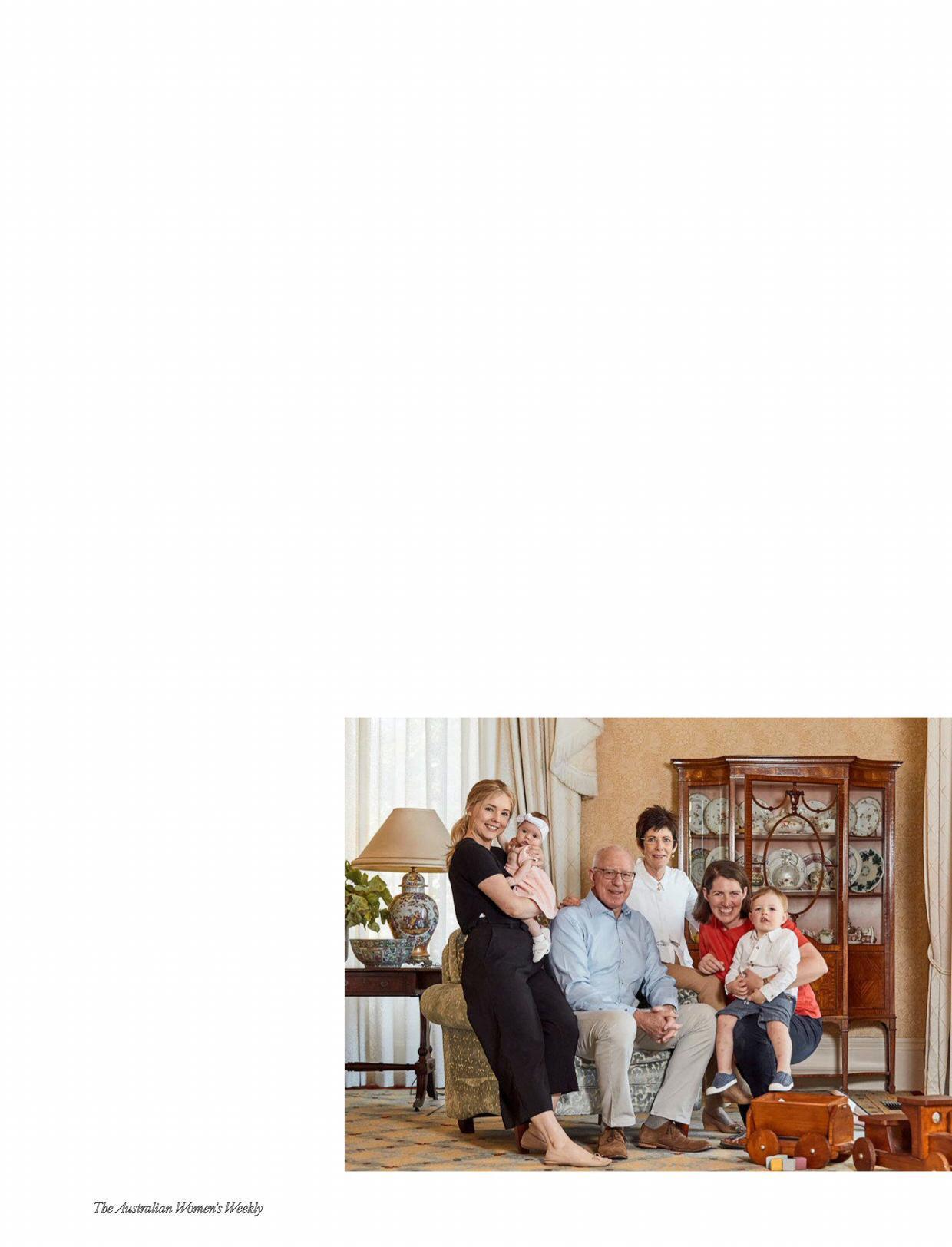

Charlie’s new conversational skill wasn’t the only major development in the Hurley family while its members were separated by the pandemic. While the senior Hurleys were confined to Canberra, their first granddaughter, Sabrina, was born to their middle child Marcus and his wife Rosanna in Sydney last August.

“It was a real joy,” says the Governor-General, even though there were no baby hugs, and for the first three months of her life, he only met Sabrina on Zoom. Mrs Hurley is quick to add that her husband is used to missing the births of his grandchildren. When their eldest daughter, Caitlin, gave birth to Charlie, the GovernorGeneral was in hospital with an injury he’d sustained while sanding back an old family bassinette for them.

Was Mrs Hurley left wondering which hospital to visit?

“Not at all,” her husband chuckles.“I know where I stand in the pecking order.”

But this time both grandparents were absent and while Mrs Hurley understands that many people lived through tougher challenges during COVID, she found the separation from her children and new grandchildren difficult.

Family is all-important to the Hurleys and, she admits, “I struggle a bit [with the idea] that perhaps I’m not a very good grandma because we’re not available. A lot of our friends can babysit or they have the grandchildren every Thursday and take them to the park. We can’t do that.

“When we do have time with them, it’s very special. When they come down to Canberra and we have leave, then we can just sit on the floor and play. And Caitlin really wants Charlie to know us. She comes over whenever we’re in Sydney. But I do feel I’m missing out on being the grandma that perhaps I could be ... I guess our time will come.”

When they were raising their own children – Caitlin (now 37), Marcus (35) and Amelia (31) – Mrs Hurley left her job as a teacher and for 15 years she was a full-time mum. The GovernorGeneral, then an army officer, was absent for long stints and the family moved often, across the UK, Germany, Malaysia, the United States and all over Australia. Yarralumla (Government House) and Admiralty House are their 28th and 29th homes in 44 years. But they don’t regret a minute of it.

“The children haven’t always been angels,” Mrs Hurley begins.“But they’ve all grown up to be beautiful people,” her husband adds. “So in that sense, I wouldn’t change anything.”

These days, the Hurleys’ public roles require that they take the much wider Australian community into their care. And since the Governor-General came to office almost three years ago, that has involved spending time with those whose lives have been rocked by one disaster after another – fires, floods, a pandemic – while still bearing up to the everyday struggles of life.

The Governor-General is endlessly surprised by people’s courage, and their willingness to share their stories.

“They just open up, out of the blue sometimes,” he says. “I think it’s because of their trust in and their respect for the office of GovernorGeneral. They’ll tell you things that they wouldn’t tell anyone else, sometimes quite unexpectedly.”

“I’ve met people who I will never, ever forget,” adds Mrs Hurley, who worked for a time as a pastoral carer in hospitals and hospices, and is a sympathetic listener. “There was one lady in particular – I would give anything to track her down and find out how she’s going. That was after the fires. We were in a big relief centre in Bairnsdale, in Gippsland, and I saw this lady who looked quite content, sitting quietly, crocheting. I thought, I won’t interrupt her, but she looked up and smiled at me. Thirty minutes later, she’d told me her life story, her history, and it had a lot of tragedy in it. She was looking after two grandchildren. Those boys were in her care when the fire came. Now she’d lost her home. There are so many stories and I write them down – I keep a diary – but I often think of that woman particularly.”

The Hurleys have been moved to tears by some of the tragedy they’ve witnessed.

“We went to Conjola Park,” the Governor-General explains. The town is perched on a steep hill overlooking a deep, blue lake on the NSW south coast. “We met a lady in the street who could stand there and point 200 metres away and say, ‘My husband died fighting the bushfire just there.’

“We went to Kangaroo Island and stood in a bus shelter in the middle of

nowhere talking to six ladies who had just lost their houses yesterday, and their husbands couldn’t come because they were out shooting stock and burying dead sheep. It was very confronting, but you’ve got to be there for them, and then you’ve got to follow up ...

“You meet people who are just on their knees. They’re on their knees but they’re not out. They know there’s a positive future out there somewhere and we have to help them get there ...”

In part, perhaps, people feel they can be open with the Hurleys because they are official, but not party political. They don’t have a barrow to push.

“And we don’t have a bag of money,” Mrs Hurley points out.

“Though sometimes I wish we did,” her husband adds.“Privilege is a word that is probably overused but we do feel privileged to be invited into so many people’s lives and experiences. We try to make sense of all this, and of what this office, this job, can offer in return.

“One thing we can do is offer reassurance that the country hasn’t forgotten these communities. Also, I make notes and when we leave, I’ll write or talk to ministers or to Shane [Fitzsimmons] at Resilience NSW, and I’ll say, ‘We saw this or heard this and it didn’t seem right.’ Or ‘You’re probably aware of this but just in case you’re not ...’ Then it’s up to them to respond, but people are very receptive.”

Visiting and revisiting these communities is a project that he says will occupy him throughout his term as Governor-General. Another is the reinvigoration of the Order of Australia, which he believes does not adequately represent the vibrance and diversity of contemporary Australia.

The representation of women among award recipients is particularly concerning. Between 1975 and 2019, women made up only 19 per cent of Companions of the Order (ACs), 21 per cent of Officers of the Order (AOs) and 24 per cent of Members of the Order (AMs). And since 1975, three-quarters of the members of the council that assesses public nominations have been men.

The Governor-General is on a personal mission to correct that, and to increase Indigenous and multicultural representation, too.

“We’ve been approaching businesses, peak bodies, state and federal governments, local members and councils about looking out in your community to see who should be acknowledged,” he says. He’s also updated the organisation’s data system. “So I can now write to peak bodies and say, ‘Here is your data for the past 25 years on women’s and men’s nominations. You’re not doing well.’”

And it’s making a difference.“Numbers of women have increased significantly over the last number of lists,” he says, “and the next list, on Australia Day, will be another step up.”

This concern for equity was also a hallmark of General Hurley’s time as Chief of the Defence Force, where he introduced systemic change to address sexual harassment and inequality, and to remove barriers to women’s full participation in combat. He was overwhelmingly considered a fair-minded and compassionate leader – qualities which have also defined his appointments as NSW Governor and then Governor-General.

After a life of military service, The Weekly asks, how has he been affected by recent allegations against Australian troops of war crimes in Afghanistan, and by the troubling rates of PTSD and suicide among those who served there?

The Governor-General sits quietly for a moment to gather his thoughts.

“Warfare is hard business,” he begins. “Sometimes people think Afghanistan was more like peacekeeping, but it wasn’t. It was war. That doesn’t excuse anything that may have happened. When you hear of things that may have occurred, it’s deeply distressing. This is not us. I’ve been a professional soldier for 40-odd years

– David Hurley

The Hurleys take a stroll with Charlie. Opposite page: With Rosanna and Sabrina (left) and Caitlin and Charlie (right).

and I know it’s not us. I just find it really distressing.”

And when the pressure leads to so much distress that veterans suffer intolerably or take their own lives ...

“If you expose human beings to that, you must anticipate change,” he insists. “People will be changed by operational military service. For many people, it’s to the good – they grow as human beings – but unfortunately, there will be a percentage who will suffer grievously from what they’ve experienced. It’s the history of warfare. It’s not a new thing. If you put people in those situations, the human mind responds to it, but our job as a society is to help those people when we get them back.”

Breaking into this sombre conversation, from across the corridor comes a wave of music. Caitlin and Charlie are playing the grand piano in the drawing room. The Hurleys are a musical family. Caitlin and Amelia both play piano beautifully, and Marcus and Rosanna are involved in musical theatre.

Mrs Hurley is renowned for the Christmas carol singing (at which she dresses as an elf) and the musicals she has produced for staff, family and friends both at Government House and Yarralumla. And she has introduced singing to almost every official event.

“I often write a song about the organisation we’re meeting with, but if not, we sing You Are My Sunshine, or a song I wrote called The Sunshine Song. Singing changes the vibe in the room. I know, when we started this, there were some who were antisinging. And there are probably still some people who think, ‘This is ridiculous. Why are we doing this?’ But you don’t seem to notice that too much anymore.”

Have there been stand-out singers?

“The National Judges Conference were brilliant,” she says. “They broke into harmony. I’d been nervous about that one. I was thinking, maybe not. But it surprises you. Then, when they were wrapping up their conference several days later, a group who had been here got up and suggested they finish the conference with You Are My Sunshine, and they did. So you have preconceptions about what organisations or people are like, but you can be totally wrong.”

Those surprises, the GovernorGeneral believes, are among the most rewarding aspects of the role. “It’s important,” he says, “because you don’t want the job to become automatic.” Another reward is having his faith in human nature, and in Australians, reaffirmed every time he and Mrs Hurley hit the road.

“There is an extraordinary richness of spirit in Australia,” he says finally. “Yes, we’ve got big issues but we’ve got great people. During the pandemic, in western Sydney and in Melbourne, people were just going out of their way to help one another. All these little organisations springing up and getting together and recognising that there was a need. We do that really well. I don’t need a survey to tell me whether Australians are good or bad, I see it every day. I always say I’m an optimist about Australia.” AWW