The Lawrence Business Magazine introduced our yearly impact issue in 2012 with the Women of Impact; ten years later, we decided to focus again on the Women of Impact in our community. We are fortunate to have so many incredible women from which to choose. But it also poses a big challenge. Unfortunately, we couldn't get all of the amazing women in this issue, and we are sure you have someone very deserving that isn't here, but along with our writers, we tried to find a collection of strong, diverse, and selfless women; individuals who reflect a multitude of different career paths and who represent various ways to make an impact.

Lawrence is and continues to be shaped by dedicated women. One woman, Elizabeth M. Watkins, was a philanthropist and a steward of education and health. She is known for her generous monetary contributions to the City of Lawrence and the University of Kansas. If you have ever come across a Lawrence building or organization with the name Watkins on it, such as The Watkins Museum of History at 11th and Mass St (and the location we chose for the cover shoot), there is a good chance its existence is the result of Elizabeth's philanthropic donations. From 1926 until her death in 1939, Elizabeth became a champion of health and education, which earned her the nickname "Lady Bountiful." The Lawrence Business Magazine celebrates Elizabeth Watkins as one of the original Women of Impact.

The Women of Impact throughout our community, whether mentioned in this issue or not, are the role models that uplift our youth and influence generations to become more impactful in their present lives. They inspire others to follow in their footsteps and leave their legacy on our future.

As we end the year, take inspiration from these women and all of those in our lives that are making a positive impact. Let's appreciate them, and do our best to honor them by making a positive impact on our neighbors and community. Please remember that all our advertisers have a stake in the local economy; we ask you to first consider them before looking to source your needs outside of the community. Try and shop locally as much as possible and avoid the urge to order online. If you find something online – see if one of our local businesses has it. We know that they would appreciate the business, and when you hear someone say, "We are all in this together," remember that our local businesses are at the center of our community.

When we Shop Local - Shop Baldwin, Eudora, Lecompton, and Lawrence (and use Local Services). We are not just supporting those businesses but giving back to our community and building a future together.

Happy Holidays, Ann Frame Hertzog Editor-in-Chief/Publisher Chief Photographer/Publisher

www.LawrenceBusinessMagazine.com

Note: Much of the information in this article is from “Experimental Autonomy: Dean Emily Taylor and the Women’s Movement at the University of Kansas,” by Kelly Sartorius, published in Kansas History: a Journal of the Central Plains, Spring 2010. Emily Taylor served as the Dean of Women at the University of Kansas (KU) from 1956 until 1974. In this position, she encouraged women students to look beyond their traditional concerns about dorm hours, social events and traditional feminine careers to greater personal independence and intellectual growth. She had a lasting impact on students at KU and across the nation in her position as Director of the Office of Women in Higher Education at the American Council on Education. While serving in this position, she helped establish a national program to identify women qualified to be high-level university administrators. She was viewed as a leader of educators by supporting for-

ward-looking women’s organizations, including those focused on the status of women.

Taylor was working at Miami University in Ohio at the time she was offered the position. Her negotiations for the job gave a clue about how she would approach the position. When Chancellor Franklin Murphy initially offered her the position of dean of women, Taylor was interested in the position because of Murphy’s progressive views on the involvement of students in their own governance. He emphasized that student personnel positions should encourage student achievement, develop leadership skills and foster personal growth. However, she was to be subordinate to Laurence C. Woodruff, who had recently been given the title Dean of Students instead of Dean of Men. Taylor refused to accept the current organization chart and requested that she report directly to the chancellor. Murphy agreed that Taylor would report to him without going through the dean of students. This allowed women (Taylor) a role in the

administration at KU. In addition, reflecting Murphy’s support for an independent role for the dean of women, Taylor’s salary was $8000 per year, $1300 more than the Dean of Men. She was also able to increase her staff. She began with one assistant in 1957, but by 1975, she supervised 11 employees and a graduate assistant. Meanwhile, the dean of men’s office depended on graduate assistants for its activities.

Through her career at KU, Emily Taylor supported initiatives that focused on women’s independence and their intellect. She was setting the agenda rather than the female students themselves. Her work with the Association of Women Students changed the focus from using rules and disciplinary action to women being more independent and in control of their lives.

Taylor wanted women’s living groups and the female students to take an active role in determining their own social standards. This was at a time when in loco parentis—the idea that university administrators would set

A woman ahead of her times, Emily Taylor gave the women of KU a sense of confidence and a drive to challenge steretypes during a time when women were treated as inferior to men.

rules that mimicked those established by parents before the women went to college—was practiced. At KU, the Associated Women Students (AWS) governed dorms and sorority houses by adopting closing hours, regulations that set hours for “men’s calling hours,” the hours women could visit men’s living quarters, and establishing a procedure for “late permission” to return after the normal closing hours. At the time Emily Taylor arrived on campus, residence halls dealt with minor infractions, while the AWS had a judiciary board to deal with more serious cases. Safety of women students was the rationale for all these rules, but if administrators were candid, they admitted that the primary purpose of these regulations was to limit time male and female students were unsupervised in order to enforce social behavior to prevent premarital sex.

Taylor indicated she was interested in the position at KU because the AWS reported only to the dean of women and the chancellor. She wanted her staff to encourage student leaders to influence and to help make university policy. She believed the females involved in women’s student government would develop leadership skills while allowing women to define their own policies. Taylor wanted female students to determine their own programming by bringing in lecturers who questioned the status quo for women in universities and encouraged them to become autonomous by developing personal behavioral standards and the confidence to apply them in their own lives without an authority dictating their personal actions, according to “Experimental Autonomy: Dean Emily Taylor and the Women’s Movement at the University of Kansas,” by Kelly Sartorius.

Taylor reorganized the AWS and established two committees: Bright Women to research KU alumnae with careers and Roles of Women to exam women’s place in society. She also changed the judiciary board to a board of standards because she wanted to downplay the disciplinary actions of the AWS. Instead, she encouraged women’s dorms and other living units to resolve the student problems that occurred. To be inclusive of all females attending the university, she expanded the prevue of the AWS to include even those living off campus. One student compared Taylor’s interaction with students as the student being a post and Taylor a pile driver. Taylor did not intend to provide traditional advice about boyfriends. In an interview with Sartorius on June 4, 1998, Taylor explained her no nonsense views.

I warned them that my advice would be very unconventional and that I had no sympathy for many things. … [One] young woman said she wanted to talk about … this awful story about this fellow that she was dating [who] was treating he so badly and [she] just went on and on. And I said … no I didn’t say anything for awhile, I just listened. And then she said, “What do you

think I should do?” And I said, “Well, I think you should get yourself another man.”

Taylor took her guidance of the AWS to a personal level by meeting with the president of the AWS Senate at her home every Sunday. She hosted receptions for AWS members and an annual overnight retreat. Anne Hoopingarner Ritter, AWS president during the 1960-61 school year, explained that Taylor asked women to think about their role in society and their reasons for attending the university. She had the women explain their plans after they graduated and expected them to consider options beyond being a wife and mother.

A sit-in by a group a women called the February Sisters in 1972 illustrated that Taylor’s ideas were taking hold. These women held a peaceful, 13-hour sit-in at the East Asian Studies Center. After meeting with university administrators including Chancellor Laurence Chalmers , the “sisters” reported they had achieved one of their goals with an announcement that a woman would chair the university’s affirmative action program. Other demands included a free day care center financed by KU. Other concessions included the appointment of a woman as vice chancellor for academic affairs, a woman administrator in the financial aid office, an autonomous women’s studies department and a women’s health program.

Though all of her accomplishments would be hard to include, Emily Taylor’s influence cannot be ignored. The following is taken from a “Tribute to Emily,” written by Casey Eike in July 1995, and provides an excellent summary of how she was viewed by her students.

Emily gave us what no one else could at the time, a belief in ourselves and in our abilities, a self-confidence we never had, even a belief that we could change the world. All that, and the chance to prove to ourselves and to others that we were becoming leaders. And, once leaders, she helped us to find our own way of challenging the usual, the stereotypes, the way it has always been. And when we were unsure and hesitant about our ability or talent, Emily would sigh, “Well,” and quote, “They said it couldn’t be done … so I didn’t even try.” Such recitation would shame us into forging ahead with our particular project or challenge, and once again we would prove to ourselves that, yes, I can do this. With her guidance, her witty nuances, her sometimes acid remarks, we finally saw the world and our place in it in a new way. And we would never be the same.

A woman among women. A mentor’s mentor. A role model which we knew we could never match. We thank you, Emily, for all that you are and all that we have become. p

Tammy Barta walked alongside her mother when she received her breast cancer diagnosis in 1993. She had seen Matthew Stein, MD, then a physician at the LMH Health Cancer Center, and knew when her mom received the news, she better prepare herself and take all precautions now in case, one day, she got the same call.

“In my mind, it was never if I would get breast cancer but when,” Barta explains. “I had prepared myself for years about what I would do if I ever found a lump. Of course, I checked myself regularly, and on my birthday in February of 2021, when I went to bed, I noticed a knot under my breast.”

She called her doctor the morning after discovering the knot, and they sent her to have a sonogram as soon as possible at the LMH Health West Campus. While nothing had appeared on Barta’s mammogram the previous November, after this mammogram, the radiologist and technician both said it looked pretty serious. “They had me in the next day for a biopsy, and just a couple of days later,

they called to confirm that it was cancer,” she says. “I was OK because I had it in my mind all these years. For my family, it was much tougher. After my husband had finished processing, we told our kids and the family.”

When Barta’s mom was going through cancer, she and her stepdad had cared for her. Her stepdad now lives with her and her family, and she says having someone who had walked this road before as a resource made a huge impact.

When it was time for treatment, Barta ended up needing chemotherapy but not radiation. She met with Jennifer Hawasli, MD, a breast surgeon with Lawrence Breast Specialists, who walked her through what was next.

“Dr. Hawasli answered all the questions I had about my surgery. She was sweet and kind and stayed positive,” Barta says. “She would affirm me that we could get this cancer out and would explain every step of the way—what I would have done, why— and it always gave me clarity knowing what was going on.”

In the coming days, she met with An-

continued to put her at ease, her knowing she was going to receive great care.

“Dr. Meyer is the sweetest man in the whole wide world. He was always reassuring and kind. Since we caught it early enough, he assured me it was only Stage 1, but we needed to move fast,” Barta says. “I met with Dr. Aldrich about breast reconstruction, and she was amazing at explaining everything. During my visit, she looked at everything she needed to, provided some wonderful suggestions and let me make my own decision on reconstruction.”

Barta remembers it all happening so quickly. She found the lump on Feb. 28, 2021. Her port was put in on March 25, and she began her journey through chemotherapy on April 6.

“From diagnosis to treatment, it all happened within a month. No one hesitated or missed a beat; it was boom, boom, boom, and I was ready for treatment,” she explains. “I truly

have to give credit to my coordinator, as well. There is a lot of information that comes your way. They gave me a printout that just gave me clear answers and schedules telling me where to be at what time. It made that portion so easy.”

Barta’s team determined she would need six rounds of chemotherapy. She would receive six different infusions when she went into treatment, and since she was HER+ (which can cause more growth of cancer cells), she would need six rounds of infusions for that diagnosis, as well. She says the nurses and medical staff were always kind and checked in often to make sure she was comfortable and doing alright.

“The team would offer me blankets and snacks, and would constantly check in and ask questions to make sure I was OK. Every time they would come care for me, they would explain exactly what they were doing,” she adds. “Though I was supposed to have six chemo infusions, by mid-July 2021, I had become incredibly sick and didn’t know if I could continue with the treatments.”

Barta’s sickness led to low magnesium and potassium, and she became anemic. She needed blood transfusions, magnesium and potassium infusions, and fluids, and later became an inpatient at LMH Health because she had nephrites (inflammation in the kidneys).

“This whole time, with any complication I had, the nurses continued to treat me wonderfully and were very responsive in getting things done and talking with me about my condition,” Barta says. “After my fifth chemo treatment, Dr. Meyer decided it would not be smart to complete the sixth. This scared me. My brain would say, ‘But what if, what if.’ Dr. Meyer talked me through this and said my body needed to heal before we began the double mastectomy and reconstruction.”

Once her body had healed, she met again with Drs. Hawasli and Aldrich to discuss surgery and reconstruction. The process was again seamless, and before she knew it, it was time for the procedure.

Barta had previously had breast-reduction surgery, so the process wasn’t completely unfamiliar. The team continued to assure her everything would be alright. After the surgery, she went home and began her recovery.

“Not too long after the surgery, I got a call from Dr. Hawasli,” Barta says. “She asked if my husband was around since he was with me every step of the way at the appointments, treatments and everything. I said yes, and she asked that I put him on speaker phone. She said she didn’t usually call, but she had to let us know some good

news. She said, ‘Tammy, we got it. We got all the cancer.’

At my next appointment with her, she couldn’t wait to give me a big hug, and I was just overjoyed. These people were now like great friends and family to me. To hear this news was incredible.”

She says her care team made her feel like she was also part of the team. There were no decisions made for Barta—they gave her all the information, made sure she felt calm and let her make the decisions that were best for her. She says she knows she made the right decision staying in Lawrence for her care.

“Years ago, I worked in IT (information technology) at LMH Health at a time where the reputation was that LMH wasn’t the best place for your care,” Barta explains. “It brings me so much joy to see how much has changed and how incredible the care that we offer our community is. I could not imagine having a better experience or a better care team. They made sure I was healthy, mentally and physically, and never made me seem like just another patient. I was always their No. 1 priority when I was in their care.”

Barta was amazed to see that even when the team members seemed like they were running 100 miles a minute, they still checked in to talk with her and make sure she was hanging in there.

“I have nothing but wonderful things to say. Even the scars from my surgery were fantastic, I don’t even see them,” she says. “I am grateful to be back to work full time and doing things with my family. If I see any member of my care team out in public, I would without a doubt give them a hug. I recommend the team at LMH Health to everyone and could not imagine receiving better care anywhere else.” p

The seeds of a life in public service were sown early in Kansas Rep. Barbara Ballard, who gained her drive toward civic duty from her allfemale high school and college, as well as with hands-on experiences during the Civil Rights Movement.

by Bob Luder, photo by Steven Hertzog

by Bob Luder, photo by Steven Hertzog

At the end of this year, Barbara Ballard will complete her 30th year as a member of the Kansas State House of Representatives, representing Lawrence’s 44th District. And having just been reelected last month—she ran unopposed—to a 15th two-year term beginning in January, at least a 31st and 32nd year in the Legislature appears certain.

At 78 years young, the ebullient and energetic Ballard shows absolutely no signs of slowing down.

“I’m asked all the time how long I’m going to keep doing this,” Ballard says from a conference room inside the Dole Institute on the University of Kansas (KU) West Campus, where she serves as associate director of Civic Engagement and Outreach. “When I wake up one morning and say, ‘That’s it,’ then that will be it. As long as I feel I’m making a difference and have energy to do it, I’ll do it. “I enjoy what I’m doing, and I hope it’s apparent I enjoy it,” she adds.

As Ballard is quick to point out, only 165 people—125 House representatives and 40 state senators—have an opportunity to serve the people of Kansas in the state Legislature at any given time, and she’s never lost sight of the honor and privilege she has been bestowed by her district constituents the last three decades.

“Serving is not easy,” she says. “You have to adjust your life to what you’re doing for your constituents. Keeping a positive outlook in what you’re doing is important.”

All evidence indicates the state’s Legislature has been the better for her service.

Since 1996, Ballard has served in House leadership and on the Appro-

priations Committee. She has been chairperson of the House Democratic Caucus and has served as ranking minority member on the social services budget and calendar and printing. She also has served on the Robert G. (Bob) Bethell Joint Committee on Home and Community Based Services and KanCare Oversight.

In 2007, the National Black Caucus of State Legislators named Ballard its Outstanding Legislator of the Year.

“Barbara is just a really nice person, a really caring person, and she listens,” says Brenda Landwehr, Representative of the state’s 105th District, which encompasses the Wichita area, and who has served for decades with Ballard on appropriations and social services budget. “She doesn’t play all the games. Social services can be very difficult. You hear some really sad stories, and it’s difficult to not get emotional and determine where the greatest needs are.

“Barbara’s been able to do that,” she continues. “She’s young at heart, and she really cares.”

Ballard grew up the second of four children. Her father was a master sergeant in the Army, but she’s quick to point out she was not brought up as a prototypical “army brat.” She only knew two homes growing up. Born in Petersburg, Virginia, the family quickly moved to Hawaii, where Ballard would spend much of her formative years.

She says when she was 14 or 15, her father was reassigned to El Paso, Texas, and it was there she received the seeds of a life in public service.

“The high school I went to in El Paso was the Loretto Academy, an all-girls Catholic high school,” she says. “All the students there were involved in so many things. That had a big impact on me.”

She says because there were no boys at Loretto, the girl students weren’t relegated to the background, as was the norm back in those days, and were actively involved in all sorts of civic endeavors. Her civic-mindedness was further bolstered when she attended Webster College, in St. Louis, which was operated by the same order of nuns that ran the Loretto Academy and also had an all-female enrollment.

During her sophomore year, in 1965, she joined a group of Webster students that flew to Montgomery, Alabama, and participated in the Selma to Montgomery protest marches.

“I remember the Western Union man (arriving with a telegram) the night before from my father giving me permission to go,” Ballard says.

While sowing the seeds of a life of public service, Ballard also found time to graduate from Webster with a degree in music performance and education.

She married Albert Ballard in 1969 and moved to Monterey, California, where she taught music and fifth grade. She originally stayed in Monterey when Albert, who also served in the Army, was reassigned to Fort Riley, Kansas, but eventually joined him in central Kansas. She would go on to earn a master’s degree in guidance and counseling, and a Ph.D. in counseling and student personnel services, both at Kansas State University.

Albert’s retirement from the Army eventually would lead to the Ballards’ moving to Lawrence when Barbara accepted a position as the director of the Emily Taylor Women’s Resource Center at KU. She was responsible for organizing activities for women students and advocating for victims of sexual assault. She later was promoted to associate dean of student life and then to assistant vice chancellor of student affairs.

In 1985, Ballard became the first African American woman to run and be elected to the Lawrence School Board. She served two terms through 1993. It was around that time that Jessie Branson, then-representative for the 44th District, announced she would be retiring and asked Ballard if she’d consider running for the seat. That began a three-decades-long career in state Legislature of which she’s grown quite fond—and proud.

Ballard has had a hand in passing much legislation through the House during her 30 years in office, but there are two pieces she says are particularly memorable.

After a constituent crashed a car into the back of a trailer that was sticking out onto a highway at night, she crafted a bill requiring all trailers to have reflector lights at the rear. What was memorable, however, was that, after the bill passed the House, it had to go through the Senate, which attached a motorcycle helmet requirement to it.

“I bet I had every motorcycle rider in the state at my door,” she laughs now. “And I had nothing to do with it.” The helmet requirement eventually was taken off, and the bill passed.

The other accomplishment that makes Ballard especially proud had to do with appropriating funding in 2019 for a comprehensive plan to repair, update and reopen the Osawatomie State Hospital, which had closed in 2015.

“I am most proud of my work on the Social Services Budget Committee over the years,” she says. “It has provided our committee many opportunities to fund services, including mental health services in Kansas, Home and Community Based Services, Kansas Department for Aging and Disability Services, Kansas Department for Children and Families, Veterans Affairs and Guardianship Program for guardianship or conservatorship services for vulnerable adults.

“Our efforts have made a difference in the quality of Kansans’ lives,” Ballard says.

Barbara Ballard has made a difference these last 30 years for the 44th District, Lawrence and Kansas.

“Barbara understands bipartisanship; she’s effective at working across the aisle,” says Paul Davis, a Lawrencebased attorney who served on the legislature with Ballard from 2003 through 2015. “Social services has always been her passion. She’s been a big voice for people in the state who don’t have a lobbyist or someone else to represent them.” p

Because of her great admiration for late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Amii Castle has always leaned toward women’s rights legislation in her study of law. And she impresses that to her students as a professor at KU. The way she sees things, she’s constantly educating others, if not in a classroom then through the publication of

written documents or letters. She likes to simplify complex subjects pertaining to the law and make the law more easily understandable, whether it be to her students or anyone else seeking her expertise. But it’s not just enough for her students to know the law. Her goal is to make her students critical thinkers about what might be happening in government and politics. She doesn’t want students to just know the facts, but be able to interpret them accurately. Finally, if she can successfully encourage more young people to vote, then she’ll consider her mission accomplished.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg. RBG is my role model not only for the opinions and dissents she wrote while a Supreme Court Justice, but more for her groundbreaking work as a lawyer in challenging laws that discriminate against women. RBG led the fight against gender discrimination and changed the legal landscape for the better in the process.

I am an educator by trade, so with that lens, I am always looking for opportunities to educate others. Whether it’s teaching in the classroom, writing letters to the editor, or preparing a presentation on a legal issue, my challenge is to break down and simplify complex subjects—usually subjects having to do with the law. I want each of my audience members to walk away understanding a legal concept that was once confusing to them. If my audience feels just a little smarter after hearing me speak or reading an article, I’ve done my job as an educator.

For most of my adult life, I was a busy attorney practicing law in downtown Kansas City. I came to teach at KU in 2016—when the political landscape really shifted. I decided then to do all I can as a professor to provide accurate and truthful information to my students and to teach them how to think critically about legal issues. By extension, I try to provide members of my community accurate and truthful information so they can think critically about what might be happening in our government and in politics. Misinformation and disinformation can’t exist in a room full of educated, critical thinkers. That’s the impact I hope I am making.

More young people voting! My daughters now have fewer constitutional rights than I have enjoyed my entire life, and we are handing the next generation a planet that’s on fire. It’s younger folks who are going to have to fix our mess, and many don’t realize they have a secret superpower right now—the ballot box. Politicians and elected officials don’t listen to people who don’t vote, so if younger folks want to be heard, they need to start voting in higher numbers. r

“My mother told me to be a lady. And for her, that meant to be your own person, be independent."

– Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Setting aside graduate school to work in the music industry may not have been the original plan, but it led Jacki Becker to realize not only her passion for music but other passions, as well.

by Nick Spacek, photo by Steven Hertzog

by Nick Spacek, photo by Steven Hertzog

The story of Jacki Becker’s life in Lawrence begins with music, an unsurprising fact for anyone who knows the owner and operator of the booking agency Up to Eleven Productions. Beginning with her time at the University of Kansas’ student-run radio station, KJHK 90.7 FM, where she started a show devoted to local music called “Plow the Fields, Martha,” in 1990, and continuing on through booking bands at The Bottleneck, tour-managing bands and on to managing her company for more than 20 years, music has been the throughline.

“I never thought I’d move here and stay,” Becker explains over coffee at Sunflower Outdoor & Bike Shop. “That’s just always the joke to me— that somehow I found Kansas more appealing than Wisconsin or anywhere else in the world—but apparently I did, and I’m glad that I have.”

Becker originally assumed she was going to graduate school, looking at going to the University of North Carolina or Duke to do women’s history or women’s studies, something like that, but business owner Brett Mosiman offered her a job at the Bottleneck, to which she said yes.

“Told my mom and dad I wasn’t going to grad school, and I was gonna book bands,” Becker laughs. “And here I am.”

While Becker doesn’t want to come across as that old person spouting off about walking 20 miles in the snow uphill both ways, she does acknowledge that when she started in the business, the job was a bit different from the way it is now. She made the poster, she made the handbills, she ran the show, she did the ticketing, she settled with the band, and she

was the runner, while now multiple people do all those jobs.

However, in the process of running around town doing things for bands, Becker became more aware of other aspects of Lawrence outside of the music scene. When people are coming in and they’re asking, “Where’s a good place to get vegetarian food?”, that makes you have to know more about the city you live in.

“Where we’re sitting right now was a veggie place called Herbivores,” Becker points out. “I think the live music industry probably kept that space alive, along with myself. I probably ate at Herbivores five days a week because it I don’t need meat. It was the perfect place to go and eat.”

Becker’s veganism is very much an important part of who she is, and it informs some of the other things she does in the community, although she is quick to explain that she’s “mostly vegan,” but she’s also from Wisconsin, and there’s something about local cheese from sheep and cows that she still really likes.

“I’ve gotten great at making cashew cheese and things like that, but cashew cheese curds don’t exist, and they probably wouldn’t squeak,” the promoter jokes. That being said, during the COVID lockdown, when there were no shows to be put on, Becker did the occasional vegan or veggie pop-up, working with what she refers to as “the wonderful family that I have at The Roost.

“If you keep challenging yourself, you can find new things to do,” Becker explains. “Do I wanna open a vegan restaurant? No, but would I like to do a vegan pop-up every now and then, and make really good food from my

garden for people? Yes. Absolutely. It’s an important piece of who I am and what I do in the community.”

COVID saw Becker’s career in music turn to activism as tours began canceling, and music venues started shutting down. Given their status as vectors for transmission, many venues were the first places to close in the towns and cities that had them, and were often the last places to reopen. Because of that, Becker partnered with Mike Logan, owner of downtown Lawrence venues The Bottleneck, Granada, and Lucia, to work with Save Our Stages, a “group of over 3,000 independent venues in 50 states and Washington D.C. that [were] banding together to ask Washington for targeted legislation to help [them] survive.”

As COVID took hold in early 2020, Becker was constantly moving shows—more than 200, by her recollection—with some rescheduled three or four times apiece until the full shutdown became apparent.

“We were doing anything we could not realizing the damage of what this was doing to us,” Becker recalls. “But then, watching a group of crazy independent humans go to D.C. and actually push for ‘Save Our Stages’ to happen? That’s beautiful. What was accomplished, I don’t think it’ll ever happen again, but it just shows you that live music independent promoters are nuts, and we will commit to anything to the extreme level, to the nth degree, and it needed to happen.”

As she points out, next to University of Kansas basketball, she thinks live music is consistently one of the most important things people have to do in this community. People can come to a space and see a show, and those people who come from out of town, they stay at a hotel or Airbnb, get coffee, get gas, eat food and go shopping in a space that’s walkable.

Being able to get about in a way that doesn’t encourage using an automobile might be the other aspect of Becker’s activism that most exemplifies her devotion to Lawrence. She rode up to the interview on her bike and can frequently be seen on it all over town and, during the years, has been part of a group that has advocated time and time again for bicycle accessibility in Lawrence. It just might be one of the more uphill battles Becker has had to fight. Live music and sustainable eating are things people can get up behind, but it seems as though folks have very strong emotional reactions to people on bikes. “One of the first committees I joined

back, I don’t even know when, was working on bicycle stuff with the City,” she recalls. “We started picking away at and trying to figure it out. We got that little two-block area on Ninth Street. I rode it, I was like, ‘Yeah, this is amazing, and we’re gonna get made so much fun of, ’cause that’s all we have, and it doesn’t go anywhere, but we did it!’ ”

In addition to architect Mike Myers and Jessica Morton, with the City of Lawrence, Becker found a group that thought the same way she did, and they started writing grants and talking about safe biking, and now, she says, she can bike almost anywhere in the city.

“There’s still lots of work to do,” Becker says. “But we’ve got it started, and

we’re making it accessible.”

All of this—Save Our Stages, veggie pop-up kitchens, bike advocacy— comes from the way Becker hopes everyone can live their life.

“I believe in a life that hopefully allows you to give time to volunteer,” Becker says, explaining that’s something she got from her parents, and they’ve always been those people. “I’ve never lived my life to be incredibly wealthy,” she explains. “I want to have enough money to live and spend my time—I guess you’d say ‘solving problems,’ but being a piece of a group of humans who are working to make sure that communities can be fed, have accessibility, can feel safe, secure and live. I like where I live, and I’d like others to enjoy it, too.” p

As a Kansas State Senator, Marci Francisco believes in doing – action – more than saying mere words. Many of those actions of directly had positive impacts on members of the Lawrence community, such as restored and affordable housing, wood-chip programs, even turn lanes on busy city streets. She reached the state senate from the ground up, serving in the late 1970s on local neighborhood associations and community advi-

sory boards before moving on to city commission. She believes in working for the community from a standpoint of responsibility, accountability and –there’s that word again – action that always comes from a place of understanding and taking into account what the people of Lawrence need.

Jessie Branson and Betty Jo Charlton, two of the members in the Kansas House of Representatives representing districts in Lawrence.

I try to change things more through what I do than what I say. I take responsibility and actions while trying to understand and take account of what others need.

Being able to point to things in our community that were a result of my actions: restored and affordable housing, the city’s wood chipping program, and the turning lane at 23rd Street that allows northbound traffic onto Massachusetts Street without stopping for a traffic signal. Also, it’s helping others understand how they can have an impact.

I decided in 1977, as a member of the Oread Neighborhood Association, to volunteer for the Community Development Block Grant Advisory Board to help improve my neighborhood. Two years later

I ran for City Commission hoping to help improve neighborhoods throughout Lawrence.

I’d like to see less waste of plastic, food, building materials, energy. r

“What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.”

– Jane Goodall

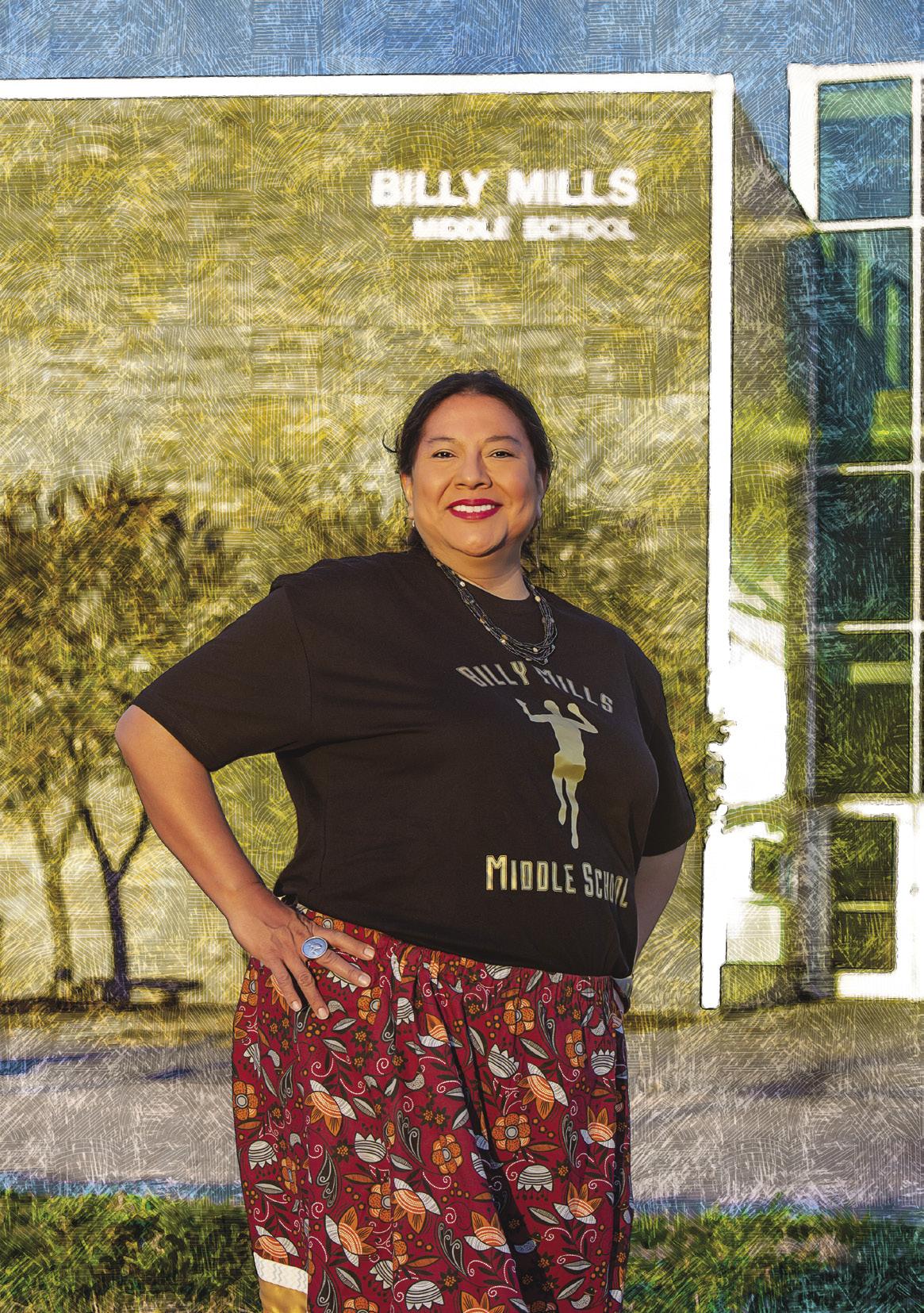

A pillar of the Indigenous community and a strong advocate for her people, Carole CadueBlackwood continues to shed a light on the racism against Native Americans in all walks of life— from sports to schools to everyday life.by Tara Trenary, photo by Steven Hertzog

On a cool morning one recent Saturday, about 15 people showed up to a Kansas City Chiefs game to protest— peacefully—at the GEHA entrance of Arrowhead Stadium. Members and supporters of Not in Our Honor, formed in 2005 by a group of Native American college students at the University of Kansas (KU) and Haskell Indian Nations University, were there to raise awareness about how detrimental the use of Native Americans as mascots in sports is. The Chiefs happen to be the last NFL organization to choose not to change its mascot.

“I’m not going to stop until it changes,” says Carole Cadue-Blackwood, USD 497 Board of Education member, case manager for The Kansas City Indian Center and enrolled member of the Kickapoo Tribe in Kansas. “It’s dismantling structural racism. People aren’t aware of how harmful the use of Native American imagery is.”

This life that she has chosen—or that has chosen her—is one of activism, community outreach, service to her people, advocacy for youth and providing mental health services for all. “She’s very justice-oriented,” explains Gaylene Crouser, executive director of the Kansas City Indian Center. “It all boils down to her people and being able to create positive social change for our community.”

In November 2022, a win for Not in Our Honor and Indigenous people alike, the Kansas Board of Education voted to retire using American Indians as mascots, helping to prevent “imagery and practices (to) seep into our publics schools,” Cadue-Blackwood says.

Cadue-Blackwood grew up in Lawrence. Her parents had moved the family here for the schools in 1978. She began her education at Sunset Hill Elementary in kindergarten and ultimately graduated from Lawrence High School in 1992. “I enjoyed the freedoms of being able to ride bikes with the neighborhood kids,” she says. “One of my favorite memories was when my parents came home from the grocery store to find us neighborhood kids playing kickball in the street.” She says her parents always encouraged their kids to get outside, and they never allowed them to say the “B” word (“bored”).

She spent many summers with her grandparents. From her grandmother, she learned “the concepts of mindfulness and the ability to examine my own biases while developing how to look through another person’s perspective,” she explains. “She (her grandmother) was highly intelligent, kind and fearless.”

From her grandfather, Cadue-Blackwood learned about discrimination, segregation and the power of words. She grew up seeing townsfolk call her grandfather “Chief” whenever they encountered him. She witnessed firsthand what he was forced to endure throughout his life (eating in the backs of restaurants and sitting on milk cartons around town) and what that kind of treatment can do to a person. This taught her how to be strong. She was called “Chief” once in high school, but only once. “I put a stop to that immediately,” she asserts.

She has always admired strong women, “my mother, my grandmothers and Wonder Woman. Specifically, in that order,” she quips. “All of them were committed to fighting the good

fight while maintaining grace and compassion.”

Cadue-Blackwood met her husband, Dennis Blackwood, in the Intertribal Club at Lawrence High School when she was a junior and he was a senior. “It was during the ’90s when seven of our Indigenous men were being killed in a rash of violence or unsolved murders,” she relates. “I wasn’t able to concentrate in school and advocated and coordinated for members of our club to protest with members from The American Indian Movement (AIM),” a grassroots movement founded in 1968 to address issues related to racism and civil rights violations against Native Americans.

The couple has three adult children. “As an Indigenous woman, I was raised with the mindset of doing everything for future generations. I took my children everywhere with me as much as possible for advocacy efforts,” she says. Cadue-Blackwood credits her parents for taking her and her siblings to their workplaces, protests, lobbying and public meetings. “I try my best to model that same behavior for them (her kids).”

She credits her first job, as a cashier at Checker’s, for directing her career down the path it has since taken. “I now advocate for a living wage and am mindful of how the cost of climate change will affect the price of a loaf of bread or an increase in utilities. I am able to help the clients I serve maximize their resources to live with dignity.”

Cadue-Blackwood says the most challenging part of her life has been maintaining harmony in work and life. “Balancing child care, school, activism and marriage have all been challenging. I am fortunate to have found the love of my life early who supports me and vice versa,” she says. “He served our country, and now I feel like it’s my time to reciprocate.”

Cadue-Blackwood says advocating for others is her “self-care.” “I grew up in a household of change agents. I like a good challenge,” she says. “I’m able to measure moments that will influence future generations—my determination to see a dream or an idea become a reality.”

She is the first USD 497 board member to have attended Lawrence public schools, K through 12, and hold degrees from Haskell and KU (an associate’s degree from Haskell, a bachelor’s degree in political science and a master’s degree in social welfare with a clinical focus, both from KU).

She serves on three site councils, the Budget and Program Evaluation Committee, Equity Advisory Committee and Educate Lawrence. “It’s my role (at USD 497) to serve as a link for the community; that means being accessible, looking out for students, keeping schools accountable for performance (and) ensuring the best education while working with reduced funding and supporting our superintendent,” she explains. “I also enjoy getting out and meeting our students. I want to hear from our most important stakeholders—our youth.”

Cadue-Blackwood works at The Kansas City Indian Center, one of only a few urban Indian centers in the country, which serves the Indigenous population of Kansas City and the greater surrounding area. “I love being a social worker,” she explains. “I have a dream job at The Kansas City Indian Center. I’m able to provide much-needed mental health services, performing community outreach and collaborating with other organizations to improve outcomes for urban Indigenous peoples.” She says she offers intensive outpatient services and facilitates a support group for those

in recovery from addiction. “I want to improve access to mental health services and improve prevention services for our students. The pandemic showed just how much mental health services are now needed more than ever.”

But Crouser says Cadue-Blackwood does so much more at the Indian Center. “Carole wears so many hats,” she explains. Case manager, social worker, leader of after-care groups, counselor, policy and advocacy work, making connections and finding resources. More importantly, “The folks that come here look at her as an auntie. She’s just a really good auntie to the people in our community.”

In addition to her work with USD 497 and the Indian Center, she is also the liaison for the United States Attorney’s Office for the Western District of Missouri for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Peoples (MMIP). She advocated for the passage of Savanna’s Act, a bill that requires the Department of Justice to “review, revise and develop law enforcement and justice protocols to address missing or murdered Native Americans.” She was appointed by Gov. Laura Kelly to serve on the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Committee to support local and state efforts to prevent delinquency and improve juvenile justice systems. “In 2019, Kansas Department of Corrections was transferring some inmates to an Arizona private prison to help alleviate overcrowding,” costing the state millions of dollars, Cadue-Blackwood explains. “I strongly believe that if we invested in our educational systems and improving access to mental health services, we could begin to see improved outcomes for our youth.”

She also is on the Douglas County Senior Services Board of Directors. She believes it’s important to include elders when working with students.

“It’s imperative to incorporate the knowledge and experience of our elders to improve outcomes for our youth. The pandemic showed how isolation played a tremendous part of the need for mental health support for the world over.”

Over the years, Cadue-Blackwood has earned her fair share of accolades. In 2022, she was nominated by the YWCA Northeast Kansas as a Woman of Excellence for community contributions. In 2020, she was appointed by Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly to the Kansas Advisory Group on Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, was appointed to the Board of Directors for the Douglas County Senior Resource Center in Lawrence and was selected to be featured on the Lawrence Habitat for Humanity’s “Women Build” Calendar for outstanding women in the community. In 2019, she was a recipient of the Dr. Precious Porras Award for Campus Advocacy and Activism, and was recognized on the Kansas State Capitol statehouse floor for advocacy work for Indigenous peoples. In 2018, she was named to Lawrence Chamber of Commerce’s “Best Grassroots Initiative” for leading the Billy Mills Middle School rededication efforts and was the recipient of the National Indian Education of the Year Award for Advocating. In 2015, she received the United Way’s “William Wallace ‘Galluzzi’ Award” for Outstanding Volunteer.

“My combined town roots, experiential knowledge and education have given me the strength and knowledge to work with multiple systems from the macro to the micro level,” she explains.

Cadue-Blackwood believes her hometown of Lawrence has great potential to become the mecca for Indigenous education. “I have matriculated my education in Lawrence. A diverse school community alone is not enough. We can continue to strive to create a truly inclusive community, one where students and adults are welcomed and supported. The work of inclusion is a responsibility held by all and done for all, person to person,” she explains.

She adds that we can do a better job toward inclusion of Indigenous people in the school curriculum while creating stronger partnerships with Haskell and KU. “Lawrence does a great job of honoring the uniqueness of each individual while embracing diverse backgrounds, values and points of view to ... prepare students for lives in a multicultural society.” The best education, she believes, occurs in “a school comprised of students, teachers and families drawn from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, cultures, races, religions and sexual orientations.”

Cadue-Blackwood says her greatest achievement thus far is leading the name-change campaign for Billy Mills Middle School, in Lawrence, the first public school in America to be renamed after a Native American, let alone a living one. “It will stand as an example that we are still here, and Billy Mills will serve as role model for others to remember their dreams.”

“Sometimes it’s hard to know if you’re moving the needle at all,” the Indian Center’s Crouser says. “She (CadueBlackwood) will work hard and stick with it when things are not easy-coming, and she’s not going to give up. If it’s important and worth doing, she’ll keep after it. That’s (Billy Mills) gonna live on, something to be proud of, and it’s not some stereotype.”

To her family, friends and colleagues, she is an agent of change for her people and her community. “Her goal is to uplift the Native American community and provide and educate all kids, not just Native kids,” she continues. “She wants to make sure we’re really being seen in a way that reflects who we are as an Indigenous people.”

Cadue-Blackwood says she’d like to continue her advocacy efforts into the future. “I would like to see myself at a ribbon cutting for a new school instead of searching for ways to maximize our underfunded schools,” she says. Ultimately, “I am able to sleep with a clear conscious. I feel that when I go into the next world, I can tell my ancestors I did the best I could to help.” p

by Darin White, photo by Steven Hertzog

A jack-of-alltrades, Kate Dinneen has her hands in not only her passion for blacksmithing and bike riding, but also acting as a role model to teens through Van Go and volunteering her time with Emergency Management for Douglas County.

Kate Dinneen thinks of various ways of having influence, including wealth or title, or, as she prefers to say, as a connector. Connectors are by definition a person or thing that links two or more things together.

In Author Malcolm Gladwell’s book “The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Difference,” he describes connectors: “The point about Connectors is that by having a foot in so many different worlds, they have the effect of bringing them all together.” This idea of influence, Dinneen believes, is also directly tied to respect and integrity.

In 1963, Dinneen’s family arrived in Lawrence so her father could teach French and linguistics at the University of Kansas. Her mother began teaching a few years later. She was born overseas in Saigon, Vietnam, where her father was stationed as a translator. When she was growing up, she wanted to be an Olympic ice skater for the Vietnam ice-skating team and planned to join after she received dual citizenship when she turned 18. However, Saigon fell before this time, and she never received dual citizenship. Dinneen has lived in Spain and France, where, because of necessity, she became fluent in Spanish and French. Soon after her return to Lawrence, she discovered an interest in and talent for playing the upright string bass. She played from this point through junior high, high school and college. She performed with the Topeka Symphony for many years as well as in the “Nutcracker” at the Lawrence Arts Center.

At one point, Dinneen discovered her love of biking and was on a path to compete in the 1992 Barcelona Olympic Games as a cyclist. She was a fivetime state champion for road and time trial in Kansas cycling. Additionally, she trained with the Masters national cycling team and rode at the Ore-Ida

Women’s Challenge, a grueling, multiday, multistage challenge race called “The Toughest Women’s Race in History,” by Isabel Best, of Rouleur magazine. Unfortunately, during training for the Olympics, she was hit by a vehicle, sustained injuries and was unable to continue to compete, crushing her second Olympic dreams.

As a cyclist, Dinneen volunteered for Friends of the Lawrence Area Trails (FLAT), which has been working to help create the Lawrence Loop as well as maintain and promote Lawrence area bike trails. She was one of the originators and chair of the board of the organization from 2017 to 2021. FLAT (named so because Lawrence is not flat, as so many people assume of Kansas) says its group “is devoted to developing, promoting and maintaining a robust, accessible trails system serving the diverse people and communities of Douglas County and Northeast Kansas.” The Lawrence Loop, as it is called, is a series of connected paved trails that circles around the city. There are only a few areas left to be finished so the entire loop is connected. When finished, it will be 22 miles long.

In addition to her passions and interests, Dinneen is a full-time blacksmith. She has been part of associations such as Artist Blacksmith’s Association of North America (ABANA) as well as other international associations, and has traveled and worked on blacksmithing projects all over the world. She worked on the Globe Theater Gates, in London, England, and received, along with others, a prestigious Tonypandy Cup award from the Worshipful Company of Blacksmiths.

Because of her love of blacksmithing, connecting and also encouraging others, Dinneen has been volunteering at the creative nonprofit Van Go, which supports and encourages teens in their own creativity. “Using art as the vehicle for self-expression, self-confidence and hope for the future, Van Go empowers young people to create their own vision of success,” according to the Van Go website.

For the last decade, Dinneen has volunteered her time teaching blacksmithing to teens. She knows most of these lessons go deeper than just hammering red hot metal and will help shape teens into healthier, more well-rounded humans. Even if these teens don’t end up using the metal-shaping skills in a trade, they will have a better understanding of and respect for the creative process.

Kristen Malloy, co-executive director of Van Go, confirms, “Kate has been an invaluable part of our Van Go family for almost 10 years, dedicating her time and sharing her many talents with not only the youth in our programs but our agency as a whole. Kate is a very accomplished blacksmith, but she is also an incredible teacher and mentor. Her compassionate character and ability to teach our youth her craft with such care, enthusiasm and intentionality is unparalleled. We are so grateful to Kate for the countless ways she supports Van Go and our entire community.”

Dinneen also hopes to influence future generations by providing practical tools— not just a hammer but ways of dealing with relationships, community and life. One area she believes most of us could improve is our ego. “If you are a good influencer, you will have to deal with ego,” she explains.

In summers, storm-chasing was something some Kansas kids did for fun. At least, it’s what Dinneen did. Eventually, this led her to a volunteer group called SKYWARN, which has locations all over the United States.

According to the National Weather Service, “To obtain critical weather information, the National Weather Service (NWS) established SKYWARN with partner organizations” as its eyes on the ground. Generally connected to the Office of Emergency Management, these volunteer groups are assigned locations or “chase” storms and radio back reports. Technology has changed, but these groups are still a necessary part of early warnings.

After a number of years with SKYWARN, Dinneen was hired by Emergency Management as part of the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s CERT (Community Emergency Response Team) program. “The CERT program educates volunteers about disaster preparedness for the hazards that may occur where they live,” according to FEMA.org. Dinneen has worked her way up during the last 15 years to duty officer and, in addition, the Douglas County CERT manager.

As a duty officer, Dinneen is on call overnights and weekends, so if anything happens requiring additional support and the opening of the operation center, she is contacted first. She could receive a call from dispatch or the incident commander, and if needed, she will contact the director and deputy director. It is important to note that Emergency Management are first responders for weather, but during any other emergency, it acts as a supporting agency. Emergency Management is the connection to the Weather Service and is responsible for watching the weather and sounding the sirens.

Emergency Management acts as support for fun events such as the KU men’s basketball team winning the NCAA National Championship in 2022 and the corresponding crowds that followed downtown, to other emergency events such as

supporting the health department during COVID-19. Dinneen acted as a volunteer and traffic coordinator for 26 mass vaccination events from Jan. 29, 2021, to April 28, 2021, at the Douglas County Fairgrounds.

CERT provides training classes twice a year, once in spring and again in fall. Dinneen says about CERT training programs: “My hope is it helps them influence their friends and family with disaster prep.”

She is currently writing an article for FEMA about the need to provide mental health support systems for volunteers, especially through peer support, as they understand what others in Emergency Management are dealing with. The piece will be the featured article in the FEMA quarterly newsletter. Dinneen continues to be influential in the community in many ways—whatever she sets her mind to. p

Jill Elmers, Common Harvest CSA, is shaping the local food system with a focus on putting sustainably grown local foods on the plates of Douglas County residents.by Anne Brockhoff, photo by Steven Hertzog

Farming, in the collective imagination, is a solitary enterprise.

Farming, in Jill Elmers’ world, is anything but.

To be sure, Elmers spends plenty of hours working solo on her Moon on the Meadow operation east of Lawrence, near the Lawrence/Douglas County line. But she approaches farming with a spirit of cooperation that prioritizes engagement with producers, organizations, civic and governmental leaders, and others throughout the community.

“I consider myself part of the food system, and that system is made up from all different kinds of people,” Elmers says. “I’m always more interested in collaborative work than in doing something on my own. We can move mountains when we work together.”

Not that it’s easy. Farming is notoriously grueling, and produce growers such as Elmers have little time during the season for anything other than planting, managing, harvesting and marketing their crops. That Elmers has through the years carved out time to serve on numerous organizational and advisory boards, and participated in countless food-policy discussions—all with an eye toward putting more sustainably grown local food on Douglas County plates—is impressive, Kevin Prather says.

“The day-to-day operations (of farming) are pretty all-encompassing,” says Prather, who with his wife, Jessi Asmussen, owns Mellowfields Farm, in Lawrence, and is one of Elmers’ business partners. “But she still makes time for all these other aspects.”

Elmers is originally from St. Louis, and she considers herself a Midwesterner at heart even though her family moved to Dallas when she was a grade-schooler. She earned an electrical engineering degree from Valparaiso University, in Indiana, then worked in Chicago before a newspaper ad for an acoustical design company drew her to Kansas City. She then moved to Lawrence. Elmers didn’t have an agricultural background, but self-sufficiency had always appealed to her. When she had the chance to take a sabbatical, she decided to check “organic farming” off her bucket list by spending a summer working for Mark Lumpe on his Wakarusa Valley Farm, south of Lawrence.

Elmers was hooked. She accepted Lumpe’s offer to continue farming a small parcel of his land and, in 2000, launched Moon on the Meadow. She bought 3½ acres in 2006; a year later, she started a CSA (community-supported agriculture) group. In 2013, she flipped her career to farm full time and do audio-visual design consulting on the side.

“I love growing food, and I love the community around the food system,” Elmers says. “It’s like having your dream job. I wake up most mornings feeling very happy.”

Elmers grows certified organic flowers, tomatoes, beets, greens, potatoes, asparagus, strawberries, cauliflower, peppers, garlic, fennel, ginger and more. Some is planted in open plots; she also has four large high tunnels (unheated, plastic-covered structures sometimes called hoop houses) and seven smaller ones to extend the season and help control for the unpredictable weather that climate change has brought about. Elmers sells much of her harvest at the Lawrence Farmers’ Market, where she has been a vendor for 21 years and now chairs its board of directors.

From that vantage point, Elmers sees how the pandemic and rising inflation affect both producers and consumers. The first sparked increased demand for local food. To meet it, the market has been “recruiting vendors like crazy” and is considering the possibility of a permanent location, she says. The second has some locals relying more regularly on the area’s farms for fresh produce.

“This is the first year ever in my life when people come to the market and say, ‘This is the cheapest place to buy food,’ ” says Elmers, who also offers delivery of online orders within Lawrence city limits. “If we can figure out how to keep (food purchases) here, we’re all going to be better off.”

We. It’s a word Elmers uses a lot when describing her operation, especially when outlining the contributions made by her five seasonal employees. Those workers are often, in fact, apprentices, some of whom she met through the Growing Growers KC program, which connects beginning farmers with established sustainable operations.

“In the farming world, it feels like there’s a lot of competition, and I don’t understand that,” Elmers says. “If I know how to do something, why am I not teaching everyone else? Why are they not teaching me?”

That many of her apprentices have gone on to grow similar products and sell them in the same venues as Moon on the Meadow might worry some people. Not Elmers.

She knows that “people in this area eat way more fruits and vegetables than local producers can grow,” says Tom Buller, who is executive director of the Kansas Rural Center (KRC). “She’s not interested in eliminating the competition but in growing the pie for everybody so we have a bigger local food system.”

He would know. Buller and his wife, Jenny, own Buller Family Farm, in Lawrence, and was one of Elmers’ early apprentices. They became partners when Elmers and the Bullers together purchased 28 acres of land in 2010, enabling both farms to expand. As Elmers’ CSA grew, she diversified its offerings by joining forces with the Bullers and Red Tractor Farm, which was owned by Jessica Pierson (also a former apprentice) and Jen Humphrey.

Those three farms, together with Juniper Hill Farms, launched the Common Harvest CSA and soon added Mellowfields Farm to its list of suppliers. The CSA is still in operation today, although it has evolved. The Bullers now sell all their produce wholesale instead of marketing direct-to-consumer. Pierson and Humphrey are still homesteading on their farm but no longer sell food retail. Juniper Hill has expanded its own retail and wholesale operations, and added on-farm pizza nights and chef’s dinners.

Mellowfields, which grows certified organic produce on the eastern edge of Lawrence, remains Elmers’ Common Harvest CSA partner. The 24-week CSA grew to 125 shares in 2022 and offers “add-ons” from Sweetlove Farm, 1900 Barker, Wild Alive Ferments, South Baldwin Farms, Stirring Soil Farm and Crooked Bar N Ranch. That Elmers has long worked with so many other businesses should come as no surprise, Mellowfields’ Prather says.

“Jill has found (collaboration) to really be an important part of how she proceeds generally in life,” he says.

Nowhere is that more true than in Elmers’ advocacy for a robust local food system that supports food production, processing, distribution, safety, waste disposal, nutrition and equity. Lawrence and Douglas County are unique in that they joined forces to address all those issues more than a decade ago by forming the Douglas County Food Policy Council (DCFPC), making it the first such entity in the state.

“There is such a wide representation of the food system,” Elmers says of the DCFPC, which was established by the Douglas County Board of Commissioners in 2010 and became a joint city-county advisory body in 2013. “People in food sales, restaurant people, farmers, nutritionists, people who work to end food insecurity—it’s a real mix.”

Elmers was an agricultural producer appointee on the council from 2012 to 2017 and served as chair for two of those years. A main priority at the time: creating a countywide food system plan using both hard data and community input. The result: a 10-year plan that was adopted by both the Douglas County Board of Commissioners and Lawrence City Commission in 2017, and addresses everything from the economic vitality of farming and food access to soil and water quality and food-waste reduction.

“Convincing everyone it was really important to have food-system coordination within our county—that was pretty big,” Elmers says.

She worked closely with the food-waste committee, helping to figure out how to collect unsold produce and share it with food pantries. That work spurred formation of Community Organized Gleaners (COG), which in 2020 collected and distributed 2,644 pounds of food from four Lawrence-area farms.

COG in 2021 joined forces with the Lawrence-Douglas County Sustainability Office and After the Harvest, a Kansas City, Missouri-based produce rescue nonprofit, to recover 17,656 pounds of food. A Community Composting and Food Waste grant from the USDA Office of Urban Agriculture financed much of that work, and other partners included the DCFPC, Just Food, The Sunrise Project, Lawrence Community Shelter, University of Kansas Center for Environmental Policy—and Elmers’ Moon on the Meadow.

“Through her leadership, (Elmers) engaged on a remarkable level with all aspects of the food system,” Elizabeth Keever says of working with Elmers on the DCFPF. Keever was, at the time, executive director of Just Food and a fellow DCFPC member; she is now chief development officer at Heartland Community Health Center.

And Elmers didn’t stop there. She and others on the DCFPC worked with city-planning staff to craft an Urban Ag text amendment that better defined urban farms, streamlined the special-use permit process for them and cleared the way for commercial production of crops and some livestock, and on-site sales of unprocessed agricultural products within city limits. The Lawrence City Commission approved that updated language in 2016.

Elmers is also a founding member of The Kansas City Food Hub, a farmer-owned cooperative formed in 2016. It aggregates the production of more than 20 farms within 125 miles of Kansas City, making locally grown produce, eggs, dairy and meats more accessible to restaurants, schools and other wholesale and retail customers throughout the region.

The Sunrise Project also benefited from Elmers’ energy. Programs include community meals and events, a community garden and orchard, a porch pantry and youth programs—all things that bring people of diverse cultures, neighborhoods, ages and socioeconomic statuses together in a former garden center at 15th and Leanard streets, which is now owned by Sunrise Green LLC. Although Elmers is no longer on The Sunrise Project’s board of directors, she’s a neighbor of sorts (Moon on the Meadow leases a greenhouse from Sunrise Green) and remains an enthusiastic supporter.

“(Elmers) has that same generosity of spirit with a lot of her work throughout the food system,” Buller says. “A lot of the time, she’s not just looking out for the best interests of her farm but for the whole community.”

That community is growing larger as Elmers becomes more involved in statewide groups including the Kansas Rural Center. The nonprofit was founded in 1979 and uses education, research and advocacy to support the long-term health of the land and the farms, ranches and communities on which it relies. Elmers has long participated in grant-funded KRC projects (such as high tunnel research, farm-to-school programs and beginning farmer and rancher resources) and joined its board of directors in 2021.

Elmers was also drawn to the Kansas Farmers Union, the state’s oldest active general farm organization, because of its commitment to shaping policies that benefit small farms while fostering sustainability. On a federal level, the National Farmers Union addresses agricultural industry consolidation and monopolies, the Food and Drug Administration’s Food Safety Modernization Act and other policy issues.

Elmers joined the KFU board in 2019 and is a county chair for the northeast Kansas chapter, which holds tours and other events in Douglas, Atchison, Franklin, Jackson, Jefferson, Johnson, Leavenworth, Miami, Osage, Shawnee, and Wyandotte counties. Locally, she works to increase membership and create opportunities for other small farmers.

Expanding the local farm base is essential, Elmers says, as climate change and economic uncertainty disrupt existing food production and distribution channels. Weather extremes such as the extended drought in California will make it harder for farmers there to reliably grow commercial produce, while high shipping costs and supply chain

issues affect distribution of what is grown. Rising interest rates, inflation, environmental worries, geopolitical instability and other factors will likely further impact the food industry. The solution?

“We need to get more of our food from Douglas County,” which means the county needs to attract more farmers committed to using sustainable practices, Elmers says.

The 2017 Census of Agriculture (the most recent year for which statistics are available; new data will be released in 2024) did show a slight uptick in the county’s farm numbers, from 945 in 2012 to 998 in 2017. But many of those are traditional grain and beef cattle operations where the cost of land and equipment pose formidable barriers to entry.

Kansas farmers are getting older, too. In 2017, their average age was 58, and only 0.01 percent were under the age of 35. That statistic doesn’t reveal how many of any age are new to the industry because the state numbers don’t distinguish between young and beginning farmers, however the 2017 Census shows that 27 percent of the country’s 3.4 million producers had been farming for 10 years or less.

What’s all that mean for Douglas County? That while there’s plenty of demand for local food here, Elmers isn’t sure who will be growing it.

“I’m in the process of learning what that next generation of farms looks like” she says. “I don’t think they look like what we see now.”

They might be urban or micro farms or something entirely different, operated by people in their 20s and 30s who want a more balanced lifestyle than agriculture typically allows for.

“Farming is hard work. It’s not a glamorous life,” Elmers says. “I think we’re going to have more small farms, and a lot of them, so people can have that work-life balance.”

Whatever their aspirations, Elmers wants to assist beginners by transitioning Moon on the Meadow into a teaching farm over the next three years. While she’s still working out how to do that, Elmers is certain about one thing: more local food is good for consumers, farmers and the region’s economy because it keeps dollars circulating in Lawrence and Douglas County.

“The local economy we have is thriving, and I want to keep it that way,” she says. “It’s amazing to watch the dollars stay.” p

Christina Haswood sees her role as a Kansas State House Representative as not only helping to shape state politics and policy, but also to represent the values of Indigenous Americans. A child of parents from the Navajo Reservation, Haswood operates from the belief that making an impact means working in good faith to be part of a solution to an issue, to leave the community better than when you arrived. Her background in public health has focused on removing or reducing barriers, for her, focusing on those Indigenous people find when leaving the reservation. She’s been a warrior for civil rights for all Indigenous people and works tirelessly in the state legislature to make lives better for her people.

My mentor is Kansas State Rep. Dr. Ponka-We Victors-Cozad who is the first Native American woman to be elected into the Kansas State Legislature. She recruited me to run for office and has been my mentor ever since. She has taught me the ropes of becoming a politician while still holding our Indigenous values.

My role models would have to be my parents. They came from the Navajo Reservation at a young age and made the tough decision to raise my brother and me off the reservation for a better life and opportunities. They taught me hard work and perseverance which have been key players in my accomplishments in life.

Perseverance has been a key part of my story. I have failed so many times from classes to not getting a specific internship or job. When I wanted to give up, my parents would lecture me to not or when to redirect to a new path. This life lesson is a great skill in politics where it is hard to get bills passed on the first try though you can not give up the fight.

Making an impact means, that you are a part of the solution to an issue, doing more good than harm, in good faith.

(I made a decision to make an impact), as my background is in public health, it is a profession where we want to improve our communities by reducing barriers. This goal to help people came from me realizing as an urban Indigenous person, I have fewer barriers to those who grew up on a reservation. I always wondered why my school was able to teach me to play the violin in 7th grade when my cousins on the rez did not have that option. This realization really hit me when I was at Haskell Indian Nations University and saw that health issues such as diabetes were still prevalent to us Natives even if we lived on or off the reservation. There are multiple obstacles we all have to overcome as Indigenous peoples and many were the cause of U.S. policy trying to kill us off - genocide. I took an American Indian Movement (AIM) class at Arizona State University and learned about the fight for our civil rights - which is not often taught about or widely known. If you look through U.S. History and American Indian Law, you will see shocking things such as Native Americans did not gain U.S. citizenship until 1924 and the American Indian Religious Freedom Act did not get signed until 1978, just 44 years ago. All of this angered me and I knew I had to get to 'the table' to continue advocating for my people.

My earliest recall of what I wanted to be when I grew up was when I was about 5 or 6, I wanted to be a police officer. Then, I learned how to make cupcakes and wanted to be a pastry chef. In high school, I started to appreciate health and medicine then followed that path to public health. I knew I wanted to improve the wellness of my community but did not envision myself to be a policymaker until I met Rep. Dr. Ponka-We Victors-Cozad and saw Congresswoman Sharice Davids and Deb Haaland (now Secretary of the Interior) win their race. Running for office became a possibility and seeing other young folks run and win for office gave me the confidence to know I want to run for office one day but I always thought it would be after I get a PhD or when I was in my 40's. The opportunity came knocking during my last semester in graduate school just before finals week and I accepted.

I would like to see the healing of our country and community with compassion. Embracing our diversities and taking care of one another, has the power to save lives. r

“Memories of our lives, of our works and our deeds will continue in others.”

– Rosa Parks

With a passion for health equity, Erica Hill has gone above and beyond to ensure all community members are afforded the right of good health without fear of being denied because of their consequences, poverty or discrimination.

by Anne Brockhoff, photo by Steven Hertzog

by Anne Brockhoff, photo by Steven Hertzog

The pandemic, race, schools—they’re all headline issues that local leaders are striving to address.

Among those leaders is Erica Hill, a health-equity advocate whose collaborative work in health care, philanthropy and education is helping build a stronger Lawrence.

“She is passionate, and she spreads that passion,” says Sheryle D’Amico, LMH Health’s senior vice president for clinical integration.

That’s most obvious at LMH Health, where Hill is director of Health Equity, Inclusion and Diversity, and at the LMH Health Foundation, where she is director of finance and strategic initiatives. But she is also past president of the Lawrence Public Schools USD 497 Board of Education and a member of the Lawrence-Douglas County Public Health Board, Heartland Regional Health Equity Council and numerous other boards and organizations. Her goal: to remove barriers to health wherever they exist.

“Equity work goes way beyond the four walls of a hospital. It goes way beyond the four walls of a school building. It’s a community effort,” Hill says.