Lincoln Center Theater Review

A publication of Lincoln Center Theater Fall 2022, Issue Number 77

Lincoln Center Theater Review Staff

Alexis Gargagliano, Editor

John Guare, Executive Editor

Anne Cattaneo, Executive Editor

Strick&Williams, Design David Leopold, Picture Editor Carol Anderson, Copy Editor

Lincoln Center Theater Board of Directors Kewsong Lee, Chair

David F. Solomon, President

Jonathan Z. Cohen, Jane Lisman Katz, Robert Pohly, and John W. Rowe, Vice Chairs

James-Keith Brown, Chair, Executive Committee Marlene Hess, Treasurer Brooke Garber Neidich, Secretary

André Bishop Producing Artistic

Annette Tapert Allen

Allison M. Blinken

Judith Byrd H. Rodgin Cohen

Ida Cole

Judy Gordon Cox Ide Dangoor Shari Eberts

Curtland E. Fields

Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Cathy Barancik Graham

David J. Greenwald

J. Tomilson Hill, Chair Emeritus

Judith Hiltz

Sandra H. Hoffen

Linda LeRoy Janklow, Chair Emeritus

Raymond Joabar Mike Kriak

Eric Kuhn

Director

Betsy Kenny Lack

Ninah Lynne

Phyllis Mailman

Ellen R. Marram

Scott M. Mills

Eric M. Mindich, Chair Emeritus

John Morning Elyse Newhouse

Rusty O'Kelley

Andrew J. Peck Katharine J. Rayner Stephanie Shuman

Laura Speyer

Leonard Tow, Vice Chair Emeritus

Tracey Travis David Warren Kaily Smith Westbrook

William Zabel, Vice Chair Emeritus Caryn Zucker

John B. Beinecke, Chair Emeritus

John S. Chalsty, Constance L. Clapp, Ellen Katz, Memrie M. Lewis, Augustus K. Oliver, Victor H. Palmieri, Elihu Rose, and Daryl Roth, Honorary Trustees

Hon. John V. Lindsay, Founding Chair Bernard Gersten, Founding Executive Producer

The Rosenthal Family Foundation— Jamie Rosenthal Wolf, Rick Rosenthal and Nancy Stephens, Directors is the Lincoln Center Theater Review’s founding and sustaining donor.

Additional support is provided by the David C. Horn Foundation.

Our deepest appreciation for the support provided to the Lincoln Center Theater Review by the Christopher Lightfoot Walker Literary Fund at Lincoln Center Theater.

To subscribe to the magazine, please go to the Lincoln Center Theater Review website—lctreview.org.

Front and back covers and spot illustration, right: illustrations by Eric Hanson. Opposite page: photo illustration of pills and capsules that look like grave crosses © Peter Hermes Furian / CanStock.

© 2020 Lincoln Center Theater, a not-for-profit organization. All rights reserved.

Issue 77

AFTERWORD SARAH RUHL 5

BELL, BOOK, AND GUACAMOLE JOHN GUARE 9

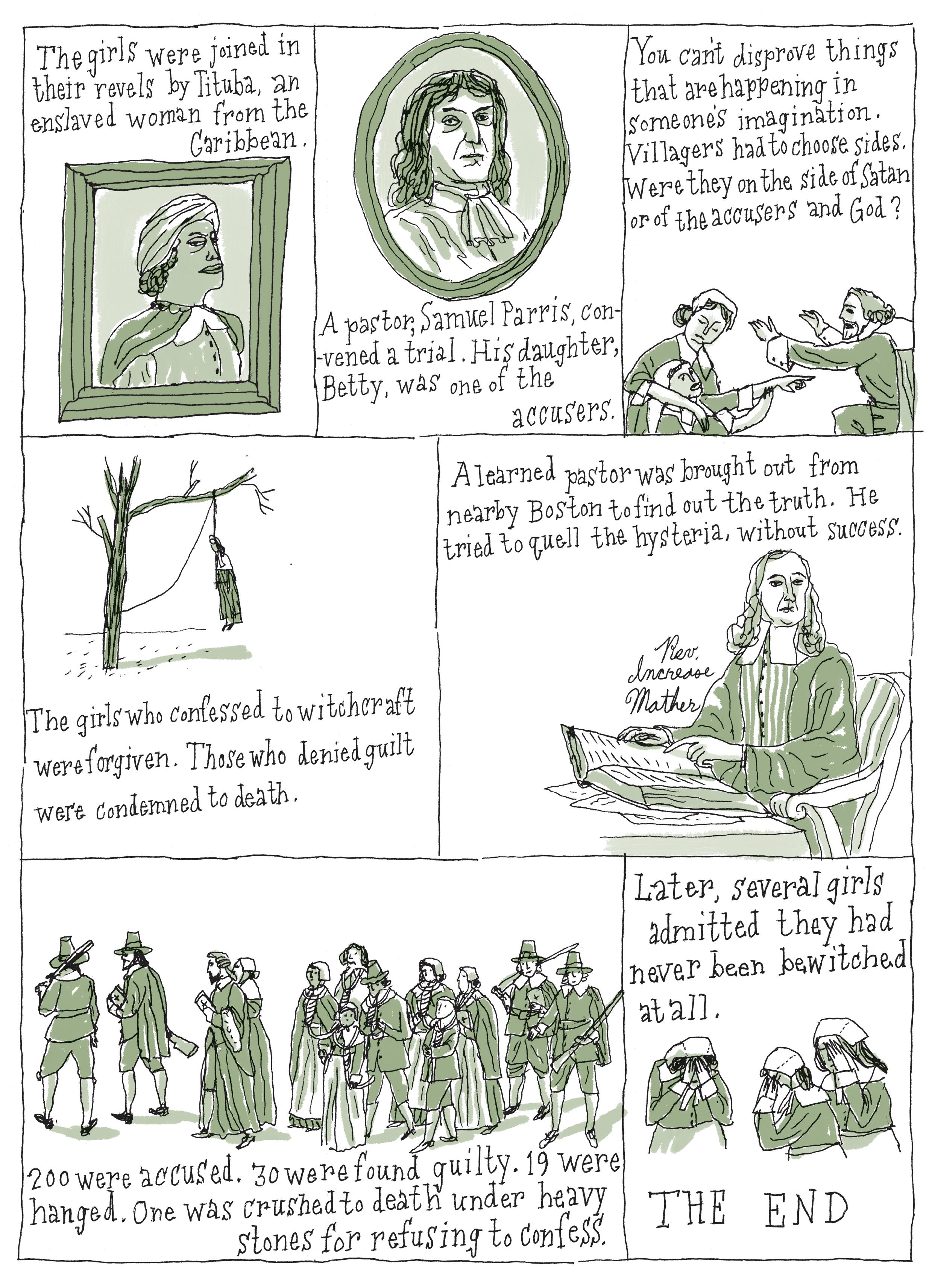

A HAUNTED PAST ERIC HANSON 12 KALEIDOSCOPE OF RAGE SORAYA CHEMALY 14 WE ALL HAVE REASONS TRAVIS N. RIEDER 17

TO WALK IN CLEAR SKIES VIRGINIA MASON RICHARDSON

A LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

In February of 2020, as we were putting the finish ing touches on the Lincoln Center Theater Review’s issue dedicated to Becky Nurse of Salem, by Sarah Ruhl, the play felt incredibly timely. Everything she had to say about the way we see women, the way narratives of evil are created, leading to the spread of fear and moral panic, and the way we examine history was reverberating in the news every day. And then, as we were about to go into our final round of copyediting, the pandemic set its grip upon New York. Life, as we’d come to expect it to be, shifted radically. Our staff optimistically talked about Becky Nurse opening in the fall—the fall of 2020, that is. But, with the ground shifting every month, Sarah Ruhl’s play seemed only to acquire more power as we marched through the pandemic, the murder of George Floyd, the presidential campaign and the election, the January 6th insurrection, and the deepening of our social divisions. I found myself thinking of Becky Nurse again and again—of the importance of perspective, of our ability and our willingness to look at history with clear eyes and curiosity, of the dangers of what Ruhl calls “historical imposition” (allowing our own personal and cultural experiences to color and distort the historical fact and record). Now, more than two years later, I’m more excited than ever to see this play live on the stage and to deliver this issue to you, our readers.

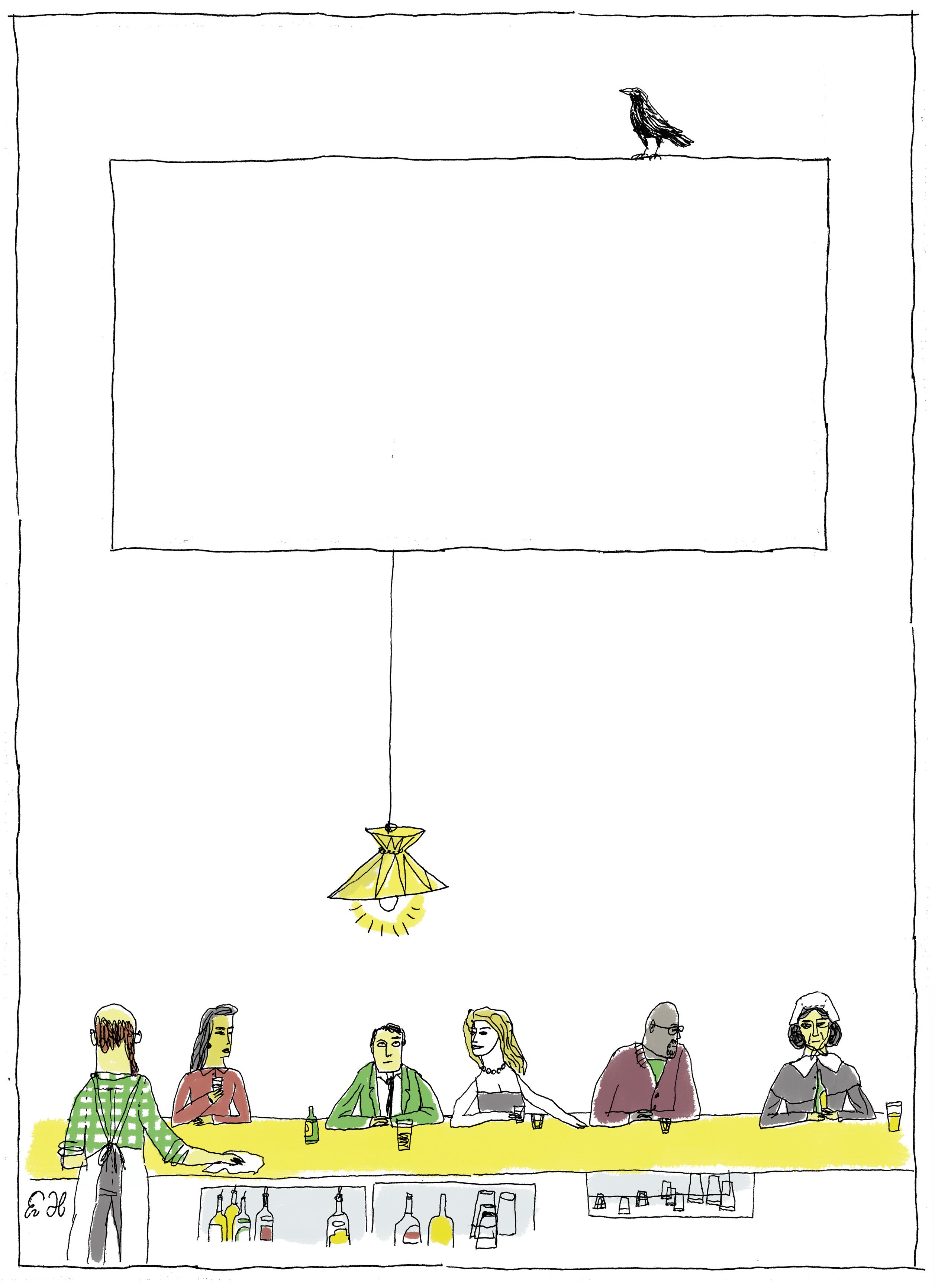

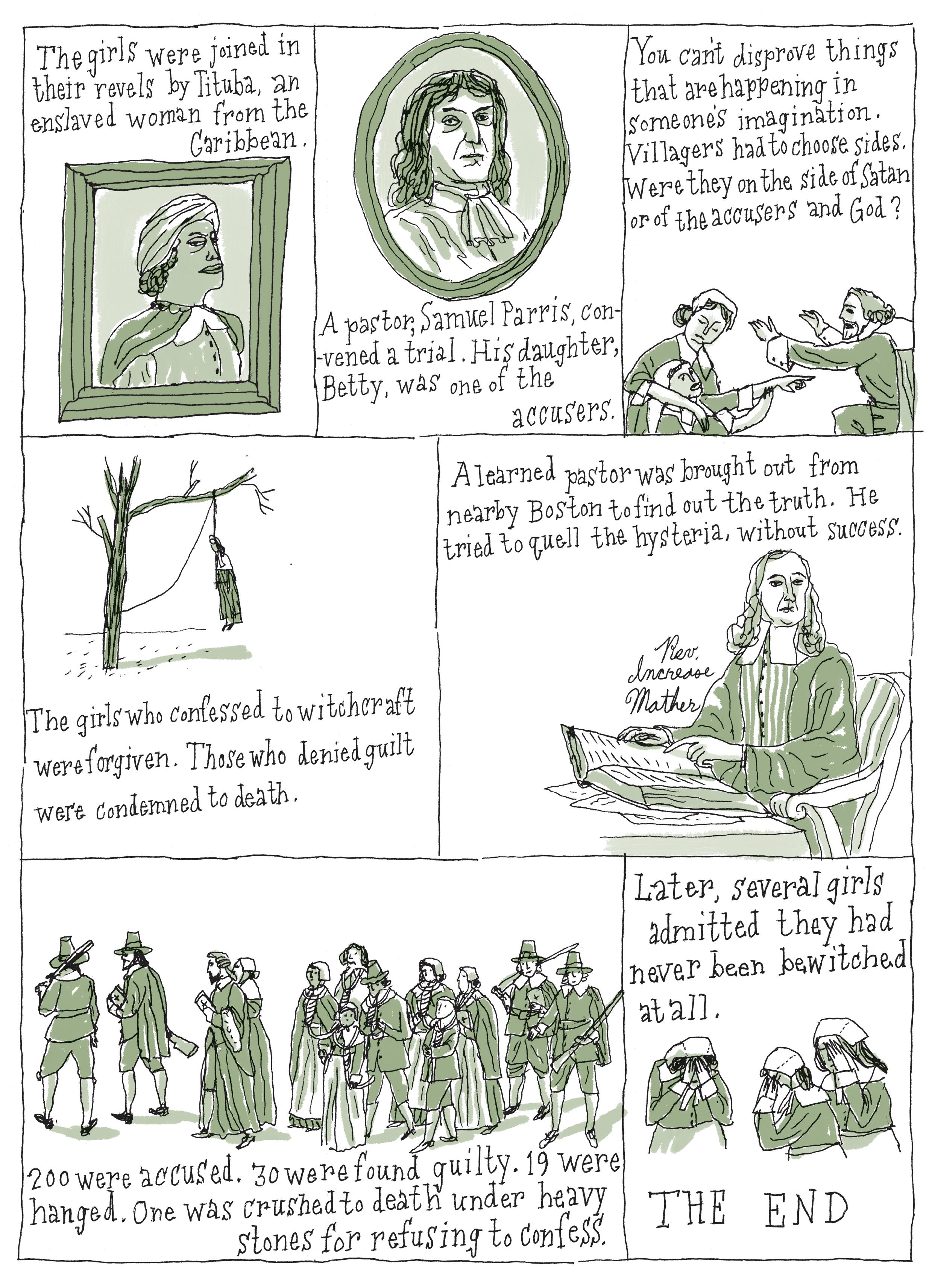

This issue of the Lincoln Center Theater Review is filled with humor, history, and witchery of one sort or another. As Lincoln Center Theater audi ences know from its previous plays, Sarah Ruhl makes every word count, from the poetry of her stage directions to the afterword of this, her most recent play, which opens the issue. Our co-executive editor John Guare fulfilled a lifetime dream and met with a practicing contemporary witch, asking her all the questions you’d want answered about money, ethics, gifts, pagan rituals, and where he’d lost his wallet. Eric Hanson created the art that graces our cover and depicts the illustrated history

of the Salem witch trials, the wit of his illustra tions a perfect match for the play’s sly and incisive humor. The journalist Soraya Chemaly writes about how deeply a modern woman’s experience is rooted in political and economic issues that can generate the anger embodied by the play’s sympathetic and comical central character. Travis Rieder is a philosopher and a bioethicist who shares the story of his opioid addiction and urges us to examine the way we judge people who suffer from addiction. Virginia Mason Richardson describes visiting Salem, Massachusetts, and the house of her eighth-greatgrandfather John Hale, a reverend, who, suspecting two young girls of witchcraft, endorsed the witch trials. Together with Ruhl’s play, these wonderful writers help us laugh and question and reexamine our history, our moral judgments, and the way we endure collective trauma—how we grieve, and how we heal.

Two years into the pandemic, those ideas have resonated with particular force for me. Has the world really changed, or have we learned to see it differently? Perhaps by seeing the world differently we can foment change.

This is our final issue with two members of our editorial staff: our friend and collaborator David Leopold, who secures the rights to our visual material, and runs the Al Hirshfeld Foundation on the side; and our brilliant, wise, indefatigable, and always kind co-executive editor Anne Cattaneo, who has retired from Lincoln Center Theater and has now joined the company of writers. She has published her first book, The Art of Dramaturgy, and is at work on her second. Together with John Guare, she founded the magazine in 1997, and for so many decades has been bringing her singularly fathomless knowledge of theater to the magazine, ensuring that it comes together with beauty and intelligence, and on time. Hers has been an extraordinary run.

Alexis Gargagliano

AFTERWORD

guilt at wanting to sleep with Marilyn Monroe. This bit of truth was passed on to me by the brilliant playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins. We were talking about The Crucible over a glass of wine at a retreat in Princeton. I was explaining to Branden that I’d recently experienced some rage after seeing a production of The Crucible. My rage had nothing to do with its being a masterpiece or not a masterpiece—I think it is a masterpiece—but, instead, with my sense that the whole concept of witchery had been redirected toward girls’ desires for older married men, which felt like an enormous historical imposition.

SARAH RUHL

August 19, 2019, Provincetown, Massachusetts

“I had not approached the witchcraft out of nowhere, or from purely social or political considerations. My own marriage of twelve years was teetering and I knew more than I wished to know about where the blame lay. That John Proctor the sinner might overturn his paralyzing personal guilt and become the most forthright voice against the madness around him was a reassurance to me, and, I suppose, an inspiration: it demonstrated that a clear moral outcry could still spring even from an ambiguously unblemished soul. Moving crabwise across the profusion of evidence, I sensed that I had at last found something of myself in it, and a play began to accumulate around this man.”

(My italics, Arthur Miller, The New Yorker)

“PROCTOR: I will make you famous for the whore you are!

ABIGAIL, grabs him: Never! I know you, John—you are this moment singing secret hallelujahs that your wife will hang!

PROCTOR, throws her down: You mad, murderous bitch!”

—Screenplay, The Crucible, by Arthur Miller

OFTEN, A PLAYWRIGHT HAS BOTH A PUBLIC WAY INTO a play and a private way into a play. Ostensibly, Arthur Miller’s The Crucible was about McCarthyism and the blacklist. But privately it was about Miller’s

“Oh,” Branden said. “Didn’t you know that Arthur Miller wanted to get with Marilyn Monroe when he wrote that play and he felt guilty about it because he was married and she was young?” I did not. But watching the brilliant documen tary Rebecca Miller made about her father, and reading Timebends, I saw that, indeed, Miller struggled with his feelings for the younger Marilyn Monroe during the writing of The Crucible. Of course, the play was also very much a parable about McCarthyism, about his friend Elia Kazan’s betrayal—but the heat of the play is the lust of John Proctor for Abigail Williams. Miller said that he saw a painting of the trials in Salem—of Abigail Williams reaching her hand toward John Proctor— and found a passage about her hand having a burning sensation when it touched Proctor. That was Miller’s way in. The real Abigail Williams was eleven years old. In the play, Miller made her seventeen. The real John Proctor was a sixty-yearold tavern keeper. Miller made him an upright farmer, age thirty-five. The real Abigail Williams never turned to prostitution; Miller writes, in Echoes Down the Corridor, that legend has it that Abigail grew up to be a whore in Boston. There is no evidence for that line of thinking, nor is there any evidence that she and John Proctor knew each other before the witch trials.

Playwrights deserve the creative liberty to enter their plays with all their emotional heat and history. I do not begrudge anyone a love story, real or fictional. After all, as my friend Ezra (the self-proclaimed maker of the best falafel in the Western world) once told me, every good story must contain a love story. I suppose what strikes me as fundamentally dishonest about The Crucible is the mixture of fact and fiction; the copious historical notes, unusually embedded in the stage directions, lead us to believe that we are watch ing actual history unfold. But we are watching what we always watch onstage—a psychic drama from the mind of a complicated individual relating

Photograph of Marilyn Monroe and Arthur Miller embracing on the lawn of Miller's home in Roxbury, Connecticut, on June 29, 1956, several hours before they were married. (AP Photo)

5

SARAH RUHL

his psyche to humankind’s larger, collective unconscious.

That The Crucible is performed at almost every high school, and is in fact the way American girls and boys understand the history of Salem, added to my frustration. I thought, All those bonnets, all those Goody Sarahs, and, really, Arthur Miller just wanted to have sex with Marilyn Monroe! I thought, All those women died, but John Proctor was the hero of the story. I thought, To this day, no one knows why the girls engaged in mass hysteria, but it probably was not the lust of one duplicitous eleven-year-old for a middle-aged barkeep.

For all of these logical reasons, I thought that I would end up writing my own historical drama about the Salem witch trials, but every time I tried to dip my toe into the seventeenth century my pen came back and told me to stay in my own era. Perhaps because I felt dwarfed by the long shadow cast by Arthur Miller’s mastery. Or perhaps I wanted to stay in the present moment because I have been undone and fascinated by the language of the witch hunt used by Donald Trump from his campaign, in which he whipped crowds into a frenzy, yelling “Lock her up!,” with those crowds often replying, “Hang the bitch!,” to his term in office, during which he has used the expression “witch hunt” hundreds of times, describing himself as the victim. Not since the burning of witches in Europe has the iconography of witchery been used with such base hypocrisy and to such nasty effect.

Although most contemporary historians have dismissed the rye-bread explanation for the symptoms of hysteria in Salem as sheer folly, we do know that rye was rare in the New World, and that it was shipped from Europe, often moldering on the long journey. And we also know that Tituba fed rye bread mixed with urine to the girls, trying to get to the bottom of their maladies. It would be ironic if the “cure” for witchcraft was actually a biological deepening and intensifying of the girls’ symptoms, which would have subsided on their own after St. Anthony’s fire left their bodies. Most contemporary historians eschew a biological expla nation, preferring post-traumatic stress from the American Indian Wars, property disputes, and the

like as more feasible. I don’t know that we’ll ever understand why those girls accused their elders of witchcraft. But what we do know is that the accusations were not a function of the lust Abigail Williams had for John Proctor.

Speaking of Tituba and the American Indian Wars, I think the historical characters of Tituba and John Indian deserve new plays of their very own. (Two contemporary novels have already been written about Tituba.) Apparently, Tituba may not have come from Barbados, as The Crucible suggests, but was, instead, from South America, a member of the Arawak tribe. The magic she was asked to do was not native to Barbados but was European witchcraft already known to the white women who asked her to perform it. The “othering” of Tituba throughout the ages, and the great mystery surrounding her own desires and inten tions, deserve investigation. I did not think that story was mine to write.

A note on the opioid crisis. Massachusetts is one of ten states that have the highest casualties for opioid overdoses in the country. In 2017, there were twenty-eight deaths per 100,000 people in Massachusetts. Sixty-four thousand Americans died of opioid overdoses in 2016, more than died in automobile accidents. It is the largest preventable cause of death for people between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five. This cluster has created what some call a lost generation, flooding the foster-care system with their children. The greatest increase in opioid deaths has been attributed to synthetic opioids like fentanyl. In a bizarre karmic loop, or bitter irony, the nineteenth-century opium trade with China, which destroyed many Chinese citizens, greatly enriched Boston. The money from the trade even helped finance cultural institutions, such as hospitals and libraries in Boston, as well as the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem. Even in nineteenth-century Boston, doctors like Dr. Fitch Edward Oliver warned against the dangers of opium, particularly for women:

“Doomed, often, to a life of disappointment, and, it may be, of physical and mental inaction, and in the smaller and more remote towns . . . deprived of all wholesome social diversion, it is not strange that nervous depression, with all its con comitant evils, should sometimes follow, —opium being discreetly selected as the safest and most agreeable remedy.”

The current focus on the opioid crisis, which disproportionally affects white Americans, is in stark contrast to the lack of attention, empathy, and resources being directed toward public-health crises that feature fewer white faces on posters.

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER REVIEW6

I THOUGHT, ALL THOSE BONNETS, ALL THOSE GOODY SARAHS AND, REALLY, ARTHUR MILLER JUST WANTED TO HAVE SEX WITH MARILYN MONROE!

As for St. Anthony’s fire, the disease comes from ergot—a poison produced by a fungus that grows on rye. The condition was named for St. Anthony, who was pursued by hallucinations of the Devil in the desert and resisted. Acute and chronic ergotism lead to convulsions, pain in the extremities, and delusions. LSD was originally synthesized from ergot, and medications derived from the fungus are used to treat migraines and Parkinson’s disease. I don’t wish to add to conspir acy theories by writing this play, nor do I want to ignore a biological explanation for hysteria.

If we are to insist on fact, it should be noted that Gallows Hill does indeed appear to be at the site overlooking a Walgreens in Salem, not a Dunkin’ Donuts. Some townspeople and amateur sleuths have claimed that the original site is now a Dunkin’ Donuts (a strange fact that led me down the rabbit hole of this play), but the Walgreens was designated in 2016 as the most probable site of the executions. Much of the evidence was wiped away in an attempt to forget, and one of the few historical sites still preserved is the Rebecca Nurse Homestead, in Danvers.

I did a reading of this play on July 19th, in Poughkeepsie, and a descendant of Rebecca Nurse, who worked at the theater, wanted to mark the

day; in 1692, July 19th was the day that Rebecca Nurse, Sarah Good, and three other women were hanged. Before she died, Nurse said, “Oh, Lord, help me! It is false! I am clear. For my life now lies in your hands.” On July 19th, before the reading, we performed a ritual at a very large tree—it is said to have the largest self-supporting branch of any tree in the United States. I cannot tell you what we did around that tree. Today, August 19th, is the day that John Proctor was hanged. John Proctor, also an innocent victim, became the cultural symbol of the witch trials (rather than the large group of women who were put to death) as a result of Arthur Miller’s outsized success in turning Proctor into a tragic hero.

Arthur Miller once lived in my neighborhood. Maybe we heard the same fog horns from the water in Brooklyn Heights while thinking about witches. There is a public way into a play and a private way in, like a worm turning over the earth. Earthworms are blind. So, frequently, are writers, especially when they’re in the midst of writing. Often, a playwright will never recognize the private way into a play. Sometimes the playwright knows and keeps it secret. Sometimes the play wright does not know while writing but realizes, with some embarrassment, at the first preview, and blushes. Sometimes the playwright does not know while writing but realizes ten years later, and, like the great Arthur Miller, writes about it in a very thick memoir. Let playwrights have their secrets, their private lusts, their compulsions— but do let us free Abigail Williams from her manu factured lust for John Proctor. When John Proctor says, “It is a whore!” and the “it” is a child called Abigail, let us consider that the real historical child was neither an “it” nor a whore.

As for my own private reason for writing this particular play, I either don’t know or I will never tell.

SARAH RUHL has written numerous plays, including How to Transcend a Happy Marriage, The Oldest Boy, and In the Next Room (or the vibrator play) and The Clean House, both of which were finalists for the Pulitzer Prize. She is the author of 44 Poems for You and 100 Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write, and teaches at the Yale School of Drama.

7

SARAH RUHL

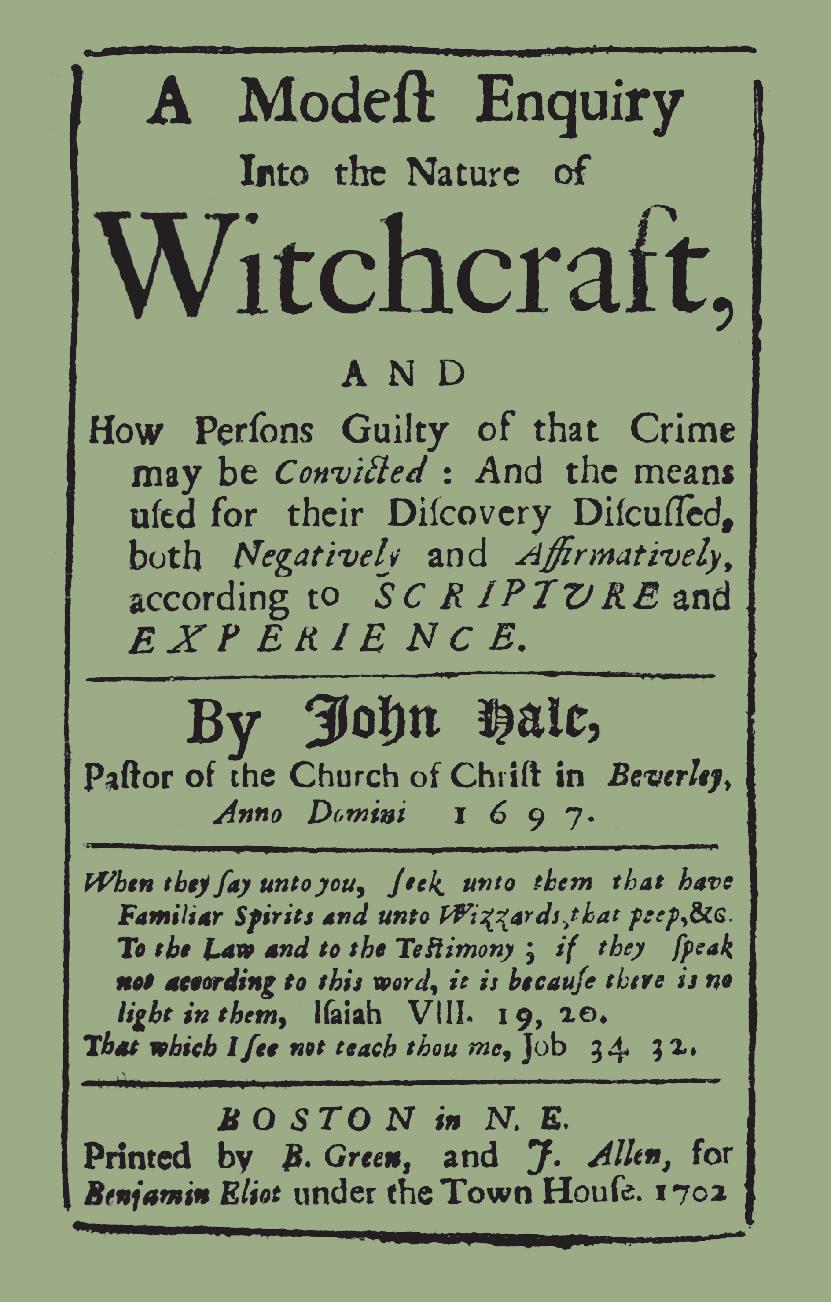

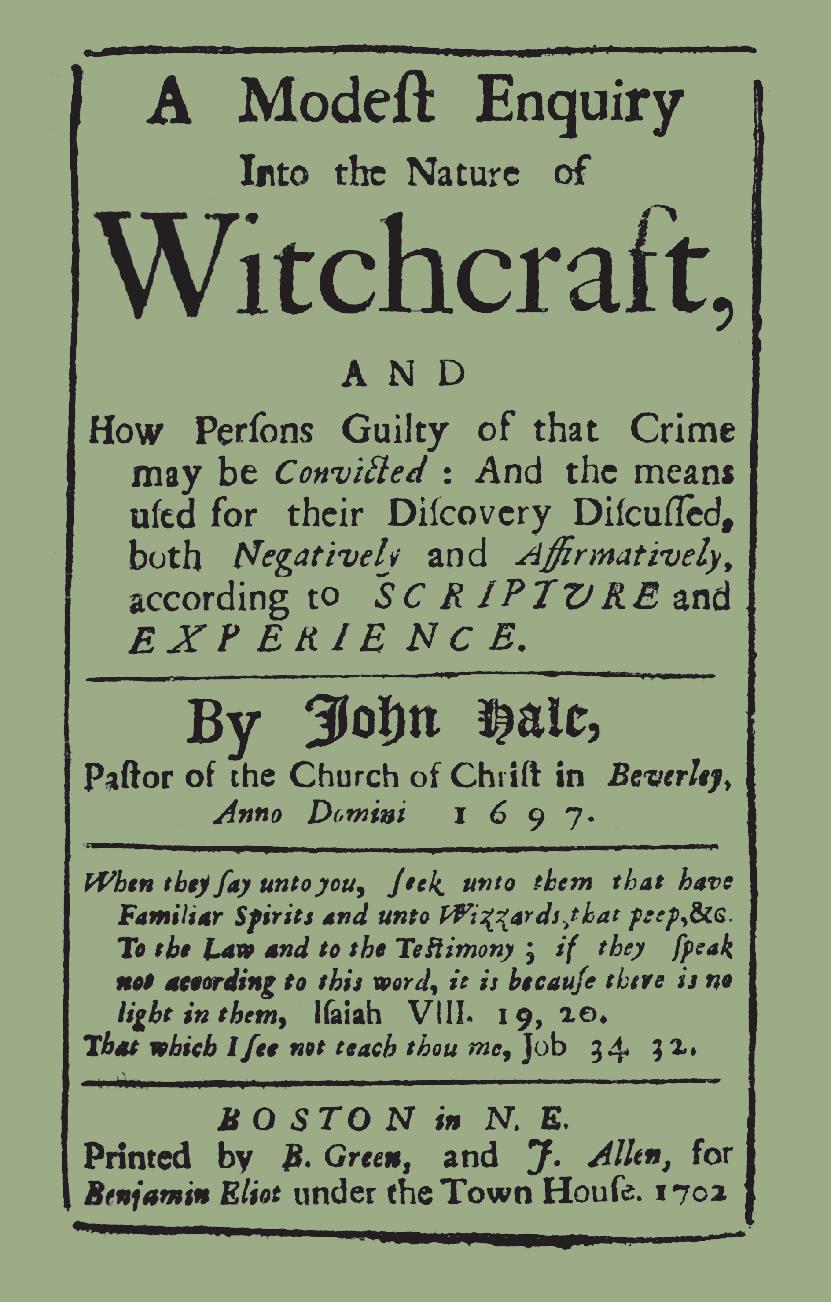

A Modest Enquiry Into the Nature of Witchcraft, by John Hale. Courtesy Danvers Archival Center, Danvers, Massachusetts.

STEILNESET

Three centuries ago in Vardø, the east ernmost town in Norway, ninety-one people were convicted of sorcery and put to death by fire. Steilneset is a memorial designed by the architect Peter Zumthor and the artist Louise Bourgeois. It stands where the victims were burned at the stake amid a stark landscape—water, land, and clouds ceaselessly shifting into one another. It is composed of two buildings. A long room with ninety-one windows, each lit with its own light, represents each of the victims. On the fabric that hangs between the windows are printed the victims’ names, dates of birth and death, and an excerpt from the trial documents. Bourgeois’ installation is a metal chair with flames rising from it, surrounded by a spiral of mirrors and blackened glass that reflects the landscape, letting the light of the flames shine through.

BELL, BOOK, AND GUACAMOLE

AS I’M LEAVING THE HOUSE TO MEET MY WITCH, I real ize that I’ve lost my credit card. In a reflex action that dates from my childhood, I say, “St. Anthony, St. Anthony, please look round. Make what’s lost now be found.” St. Anthony doesn’t comply. I can’t be late, and I have enough cash for lunch. I get off the subway at Wall Street and get lost in that downtown maze, looking for a Mexican restaurant that has alternate addresses on Pearl Street and Stone Street. A woman walking a dog becomes my guide. “Are you a witch?” I ask. “I’m a dog walker,” she says.

I arrive at the cantina. A mariachi band is playing. A blond woman waves to me. When we meet, I say, “You’re the witch,” and I said her name. She said, “Yes, but please do not say my given name. Because of the purpose of this meeting, refer to me only by my craft name, Sommeil.”

She looks as if she might be a distant cousin of Sarah Ruhl’s. “How did you recognize me?” I asked.

“I Googled you.”

“Can you help me find my credit card?” I said, getting straight to the point.

“I’d invoke St. Anthony.”

“I want a witch, not a Catholic.”

“You can be a Catholic or a Jew or an atheist and still be a witch,” Sommeil said. “Catholicism is a perfect gateway for witches. Catholics invoke specific saints for specific tasks. Witches invoke other deities.”

“You swear you’re a witch?”

“I am a witch.”

“Who’ll be the Democratic nominee?” I asked.

“The witches in Macbeth had the power to predict the

9

JOHN GUARE

Photographs of the Steilneset Memorial © Andrew Meredith, 2020.

JOHN GUARE

future,” she said. “I don’t have that power.”

“What about the witches of Salem?” I said.

“They weren’t witches. They were accused of being witches.”

“What were they?” “Devout Christians.”

We order.

“Were you born a witch?” I asked.

“I was raised as a Catholic, but in terms of senses outside of the usual four, I didn’t see any evidence of certain gifts until I was twelve and in the throes of puberty. My grandfather—I had never met him; I just knew who he was when he communicated with me— said to me very clearly that he had a message for my father: ‘Tell my son to cut it out, that he’s just like me.’

I relayed the message to my father, who immediately left the room. That was my first inkling that the other side and I had an affinity.”

“Were you frightened?”

“Why? It was my grandfather.”

“Is being a witch hereditary?”

“My grandmother’s father had healing powers. People with ailments asked him to lay his hands on their bodies. My mother’s grandmother had visitations, but neither of them called themselves witches. We’re all animals, but as humans some of us are unaware of our relation to the animal world and the language of instinct.”

“Do the dead contact you regularly?”

“Entities introduce themselves to me,” she said. “I know they’ve passed on to the other side. I don’t sit in the dark and use a Ouija board. They just talk to me at any time, under any circumstance. I listen. If I feel it’s appropriate, I pass on what they tell me.”

“If not a Ouija board, what do you need?”

“A medium depends on time and space and the fluidity of their interchangeable barriers. Mediums are able to access the beyond because they—we—are ungrounded instruments that can transmit energy and

have energy transmitted to us. Not everyone has the ability to do this. In terms of electricity, most people are grounded. I’m an antenna.”

“How do witches feel about quantum physics?” I asked.

“I’m an admirer of science. I don’t discount or scoff at science the way climate-change deniers do. We all live side by side.”

“Do you run séances? Any messages for me? Hi, Mom.”

“I can. But I’m careful about what I relate and if I will do it.”

“Why?”

“Sometimes spirits aren’t available. Sometimes I feel that the living are better off not knowing.”

“How often do they show up?”

“I am working on boundaries with my contacts,” Sommeil went on to explain. “Sometimes entities slip through the cracks. I generally can make contact if I try. I charge a minimal amount of money and don’t spend much time on marketing. If people are meant to find me, they will.”

“So you can be a witch and be unethical?”

“Can witches be unethical? Of course they can. They are human like anyone else.”

“Oh, yes.”

“You don’t make any money out of your gift?”

“Not really.”

“How does a witch support herself?”

“I work as an office manager at a telecommunications company.”

“Do they know you’re a witch?”

“Oh, no, and I don’t let them know. The general popu lation don’t understand witches. Some either laugh at us or dismiss us or are afraid of us. If you’ve ever been to a Pagan Pride Day march, you’d be surprised at the protests.”

“When is Pagan Pride Day?”

“Usually in September. Around the festival of Mabon. Harvesttime. Reap what you sow.”

“Then what is a witch?”

“A witch is a blanket term for pagans,” Sommeil said.

“Witches are generally pro-nature. We respect the earth. Many of us are activists. You’ll find us among all religions and occupations, including the sciences— botany (I’m an avid gardener), astronomy. For myself, I will always be a student of psychology. I revere Reich, who believed our problems to be located in our bodies, not just in our minds.”

“Can you learn to be a witch?”

“A pagan community can illuminate a path for you, but there are certain things that cannot be taught.”

“Suddenly, I’m remembering a play by John Van Druten, from the fifties, that became a movie: Bell, Book and Candle. Kim Novak played a witch

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER REVIEW10

Illustrations on this page and the following spread © Eric Hanson.

Witchcraft is a landing pad for people on the periphery, who want to become more aware of their relation to the natural and the supernatural world.

“Yes, our coven does cast spells, but you have to be careful. Any spell you cast on someone else can come back to you threefold. You have to be prepared for what happens.”

“What kind of schooling would I receive in your coven?”

in Greenwich Village who would lose her powers if she fell in love with Jimmy Stewart. Talk about high stakes.”

“You can be in love and be a witch, whether the other person’s a witch or not,” Sommeil said.

“Are you in love?”

“I have a beau who’s not a witch. He’s an Irish musician, but he does practice horary astrology.”

“Which is—?”

“You answer a question by building the horoscope of the question at the exact time you asked it.”

“Do you know other witches?”

“I belong to Grailwood coven. We meet eight times a year for the Sabbats, as well as for classes.”

“What makes a witch’s Sabbat?”

“Four are the astronomical equinoxes, and solstices. The other four represent traditional holidays in between. They are based on pre-Christian customs, as well as on movements of the sun.”

“Do you wear conical hats and capes with crescent moons?” I said, unable to resist.

“We can really go over the top or we can dress like anyone else. We are a mixed bag.”

“Can you join a coven if you’re not a witch?”

“No, that wouldn’t make sense. Though it’s not required that you have the special gifts of a witch to join a coven. Most people don’t have those gifts; they just want to learn and worship. A coven is a safe meeting place for people with an interest in alternate ways of thinking and alternate religions. Witchcraft is a landing pad for people on the periphery, who want to become more aware of their relation to the natural and the supernatural world.”

“And your coven fills that need.”

“I found a community that doesn’t make me feel like a freak,” she said. “The pagan community has blessed me with eyes to see my path.”

“Which is?”

“To live in the truth, as it’s revealed to me.”

“So, if I wanted, I could join a coven.”

“Yes. If everyone felt that was mutually beneficial and you wanted to be a witch.”

“Do you cast spells? I think I’d be good at that.”

“Studies with my high priestess, who guides me and is a third-degree witch. We meet as often as we can, and learn about the history of paganism, about different pantheons, about invoking deity, about the formality of ritual, about our own personal growth, and about activism for the earth and for animals. These lessons and rituals have inspired me to paint deities like Brigid and the Morrigan. I create objects like wands for ritual. There is an unending inspiration here for me.”

“You’re an artist?”

“I’m a painter, I’m a singer.”

“Your high priestess is third degree. How many degrees are there?”

“Three. I’ve been in the coven for seven years, and I’m still first degree.”

“Who decides what degree you are?”

“Your high priestess, or high priest, decides where you are. There is no overlying curriculum.”

Sommeil had to get back to work.

“If you’re in a crisis, to whom do you turn?”

I asked, trying to get in one final question.

“My best friend.”

“Is she a witch?”

“Oh, no, but we are twin flames. Whatever I’m going through, she’s going through.”

I had to confess, I was totally charmed.

By the way, when I got home I found my credit card under the bed, where I had looked before. Sorry, St. Anthony. Sommeil the witch, my very own per sonal first-degree witch, gets full credit.

JOHN

is the co-executive editor of the Lincoln Center Theater Review and

.

11

GUARE

has written many plays, including The House of Blue Leaves; Six Degrees of Separation, a Pulitzer Prize finalist, A Free Man of Color; Chaucer in Rome; and most recently, Nantucket Sleigh Ride

JOHN GUARE

KALEIDOSCOPE OF RAGE

working multiple jobs for low, unfair wages, usually trying to feed their families. Reproductive injustices have resulted in our having the highest (and growing) maternal death rates in the indus trialized world, particularly for Black women. Women’s human right to control their bodies and their reproduction is under constant threat. Domestic violence, stalking, and rape are pervasive in our society, and yet somehow difficult for our criminal-justice system to address. Less than three percent of rapists ever see the inside of a jail. We tend to think of what happens to women as “social” issues, but, in fact, they are deeply political and economic issues. And they fill women with anger, and leave us spent.

SORAYA CHEMALY

SARAH RUHL’S PLAY BECKY NURSE OF SALEM gets right to the point: the protagonist, Becky, is fired for using offensive language in front of teenagers. In other words, she, the descendant of Rebecca Nurse, a woman who was convicted of witchcraft and killed during the witch trials, is fired for . . . cursing. And she is truth-telling about men when it happens. It’s enough to make your blood boil. It certainly makes Becky’s boil. She curses some more and makes off, a literal thief, with a—thanks to her—no longer immobilized wax figure of her unfairly treated ancestor. So begins a whip-smart and engaging refutation of contemporary expressions of misogyny, replete, in our political chaos, with men using words like “witch hunt” and conservative crowds chanting, still, “Lock her up.” There is nothing new about strong-willed women being maligned as witches, or, apparently, about those who would rather cast their stories as vic timizations of men being silenced.

Ruhl’s world is a depiction of a woman trying to survive in an era of global backlash against women: our equality, health, rights, safety, and political leadership. In the U.S., women are an overwhelming majority of the nation’s poor,

In the play, Becky’s life is precarious and hard. She undergoes tribulations, sadness, and injustice. She is newly jobless, in mourning, trying to care for a sick grandchild, worried, exhausted, and in near-constant pain. Yet she is sharp-witted, resil ient, funny, and energetic. She’s older, poor and stressed, but she has the audacity to have a love interest. And sex. She drinks during her lunch break. Once in a while, she admits, to herself and to us, “The sad is so big and the mad is so big sometimes they cancel each other out and all I am is numb.”

Women in the U.S. report experiencing more than twice the levels of stress that men do, especially the vicarious stress resulting from disproportionate responsibility for care. Girls and women also experience higher rates of chronic pain, auto immune disorders, cardiovascular ailments, selfharm, anxiety, depression, mental distress, eating disorders—all “female” ailments that, interestingly, share the quality of deeply suppressed anger and “other-focusedness.” The physical demands of caring, with little or no pay or help, are supposed to bring psychic joy, the job of caring being women’s “natural” lot. Generally speaking, when asked how we are, we don’t say, “Systemic discrimina tion is enraging me.” Instead, we punt to the more acceptable, “I’m stressed.” “I’m exhausted.”

Not Becky.

She’s mad, and she says so. She’s mad at Bob. She’s mad at her dead daughter. She’s mad at her employer. She’s mad at Gail, her granddaughter, and at her boyfriend, Stan. “Sometimes I walk around thinking, I’d like to take my shoe off and just throw it at a person,” she explains, before hilariously taking her shoes off and throwing them at people.

Her rage is kaleidoscopic, filtering through her words, her actions, and the state of her body. She is driven by need and by desire, but anger is more often what propels her to act. She won’t shy away

Sculpture on this page and the following page: Minchin Tung, The Birth of a New Hero II © 2019. Camphor wood. Courtesy of Nou Gallery, Taiwan.

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER REVIEW14

BECKY’S RAGE IS KALEIDOSCOPIC, FILTERING THROUGH HER WORDS, HER ACTIONS, AND THE STATE OF HER BODY. SHE IS DRIVEN BY NEED AND BY DESIRE, BUT ANGER IS MORE OFTEN WHAT PROPELS HER TO ACT.

from or ignore the hard facts but is pragmatic and honest about them, demanding the same of others.

Demanding the truth is hard these days. For women, truth-telling often directly implicates men’s bad behavior. MeToo and Time’s Up are movements that hold men accountable and insist that treatment of individual women by abusive men is both a social and an institutional plague. When you are a woman who insists on the truth and on justice, things get ugly fast. As we have seen, through cases like Bill Cosby’s and Harvey Weinstein’s, it takes dozens or hundreds of women to bring just one man in an infinite pool close to accountability. The context for these confrontations is one of increasingly evident hostility toward women and their rights. In the buildup to the 2016 election, a significant percentage of the population engaged in what can only be described as obscene festivals of misogyny and hate. Effigies of Hillary Clinton, for example, were burned, caged, hanged, shot at during Trump rallies.

Those images and language shocked some people, but for those of us who write about and engage in feminist activism, the kind of sexism and racism that we now see openly on display has

always been evident. Proto-authoritarian rhetoric and a global Internet have primarily brought ageold and dark networks of hatred into the light of day. What has been shocking and enraging, how ever, is to watch those networks gain legitimate and consequential power. With that power they are dismantling decades of laws, regulations, and social protections for the nation’s most vulnerable people, especially those which free women from the bounds of their control. A witch hunt at scale? Ruhl, and so Becky, can’t resist the draw of time less comparisons. “I mean, who puts a child in a cage with her mother?” Becky asks at one point. “You could say the whole witch business started because of all the dead babies,” she says at another.

Every day I ask myself, What were women and girls supposed to make of the treatment of Hillary Clinton, the most powerful woman in the country, one who was voted the most admired in America year after year? What were boys and men to make of this? What does it really mean that the majority of American voters simply can not bring themselves, particularly if they are men, to see the words “woman president” as anything other than a disorienting oxymoron. It’s a world in which we are expected to smile and accept that, while men move through the world, women are supposed to be still, allowing men and the world to move through them.

There are consequences to this treatment of women, and those consequences look a lot like Becky’s chaotic and high-risk life. Like many women, in anger she advances, throwing over inca pacitating exhaustion and the numbness of sor row. She is coming and going, a perpetual motion machine. She runs, she steals, she fights, she lies, she defends herself, and she says exactly what is on her mind. No matter how bad things get— poverty, abuse, drug addiction, depression, death— Becky keeps going. Unlike her ancestor, however, she uses her voice, knows what’s happening, and is trying to keep her head above water.

All this strife takes a toll on a woman’s body, and Becky’s body becomes the crucible of the play. The alchemy of anger and sorrow and loss have left her racked with unbearable pain. That combination is inseparable from her experience as a mother, and yet, through it all, she laughs, loves, hugs her grand daughter, and seduces her lifelong love. Her anger, full of hope and desperation, is what drives her.

A significant source of Becky’s impoverish ment and pain is directly tied to motherhood. If you have been a mother, if you have given birth, the entanglement of feelings, needs, and body is

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER REVIEW16

DEMANDING THE TRUTH IS HARD THESE DAYS. FOR WOMEN, TRUTH-TELLING OFTEN DIRECTLY IMPLICATES MEN’S BAD BEHAVIOR.

completely familiar. As women, our society accepts, even encourages us, to be angry as mothers, on behalf of others, but does not accept our being angry about the toll motherhood takes on us, the costs we incur in parenting.

Motherhood and, along with it, daughterhood also, however, bring solidarity and support. Just as Becky seeks the truth of her ancestor Rebecca’s plight, it is other women who see her maternal pain and the anger she feels. They don’t revile her for them but, rather, coalesce around her. Today, that coalescing of women around anger and pain— as evidenced by women’s organizing, community building, letter writing, postcard sending, march ing, voting—is visible in the world outside the play as well.

Becky’s granddaughter even writes a new epilogue for her school’s performance of The Crucible:“Every time another girl takes a bow in this play another lie is told about history and how the lust of young women destroys good men.”

In that phrase, “lust” and “anger” are easily interchangeable. Becky’s anger doesn’t kill her or chase those who love her away. It advances her and draws them closer. Becky’s anger is a vital part of a complex person asking people to see her, struggling to hold on to her humanity.

SORAYA CHEMALY is an award-winning journalist. She writes about and speaks frequently on topics related to free speech, sexualized violence, data, and technology. She is also a co-founder and director of the Women’s Media Center Speech Project, which is dedicated to expanding women’s civic and political participation. Her recent book, Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women’s Anger, was named a best book of 2018 by Fast Company, Psychology Today, Book Riot, Autostraddle, and the Washington Post.

17 SORAYA CHEMALY

IF YOU HAVE GIVEN BIRTH, THE ENTANGLEMENT OF FEELINGS, NEEDS, AND BODY IS COMPLETELY FAMILIAR.

WE ALL HAVE REASONS

TRAVIS N. RIEDER

IN MY OWN LIFE, I’VE DISCOVERED two very powerful reasons to take drugs. My drug of choice happened to be legal and prescribed, but that’s rather by accident.

After my foot was crushed in a motorcycle accident, I never wanted anything so bad in my life as I wanted morphine. Bones had splintered into tiny shards that ripped through soft tissue, tearing a large hole in the bottom of my foot, and the pain was unlike anything I had ever experienced. As those first hours, post-accident, turned into days and then weeks of surgery and constant retrauma tizing of my flesh, I wanted—needed—ever more, ever-stronger drugs. Intravenous morphine was traded in for the more potent hydromorphone and fentanyl; the oxycodone pills I was transitioned onto before I left the hospital only just took the edge off. For months, I watched the clock and duti fully popped pills every four hours.

Until I was told to stop. Too much time had passed, I was told. You shouldn’t be on so much pain medicine, I was told. So I tried to quit.

And then came the second very good reason to take drugs: avoiding withdrawal.

The early stages of withdrawal were akin to the worst flu imaginable—nausea, sweats, chills— combined with screaming pain from my now undermedicated foot. As it progressed, I developed tremors, which kept me from sleeping or getting any kind of meaningful rest. The flu-like symptoms tortured me around the clock, and time slowed to a crawl.

The worst symptom, however, was the depression. As my misery continued and worsened

for days, and then weeks, I began to believe that I would never recover. My body and brain were broken beyond repair, and I would never find my way out. As the darkness closed in, I found myself thinking more and more about the drugs: pop a pill (two would be even better), and the world would right itself. Go back on those meds, and I could put an end to the suffering.

But I never did. Despite the withdrawal, I continued my awful, fumbling taper, and withdrew for twenty-nine days. Because I knew that if I ever went back on the pills I’d be on them forever; I simply wouldn’t be able to make myself do this again. And so I writhed and cried and spent entire nights on the bathroom floor; but, eventually, I made it out.

When I tell this story—especially in such an abbreviated form—I come off sounding good. People tell me, in an awed voice, that I must be profoundly strong to cold-turkey my way off these powerful drugs. Thank God for my strength.

If only.

I wasn’t strong; I was pathetic. I was carried across the finish line, sobbing and desperate the whole time, by my incredible partner, and the hope I was given by my toddler. I desperately wanted to be a functioning father and husband again.

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER REVIEW18

Above: Chemist, knitted artwork by Susie Freeman and Dr. Liz Lee © www.pharmacopoeia-art.net.

I had also—just before the accident—been offered my first permanent faculty position at Johns Hopkins, and I couldn’t wait to start the career for which I had spent so many years train ing. Dangling just out of reach was the prospect of a perfect life, with my perfect family and my perfect job. All I had to do was survive, and it was mine.

When I finally came out of withdrawal, and began to gain some distance from the trauma, my good fortune and my privilege haunted me. I began to understand how lucky I had been to be supported and to have such powerful reasons not to take the pills. And the question that kept me awake was: What happens to all the people who aren’t so lucky?

But that’s a rhetorical question, isn’t it? We know what happens to many of them. We know what happens because we live in the era of “America’s Opioid Epidemic.” We live at a time when millions of people suffer from active opioiduse disorder, and tens of thousands of them die from overdose every year.

Big numbers are hard, and so just throwing out statistics—tens of thousands of people die from opioid overdose each year—doesn’t mean much to most people. So let’s make sure we have context. More people now die each year from opioid overdose than from automobile accidents. More, too, than from gun violence.

If that still doesn’t shake you to your core, let’s talk about overdose death from all drugs: More Americans died in 2017 from drug overdose than died in the entire Vietnam War.

I was lucky because I had a support system, and every reason in the world to return to my life as I had known it. Not everyone has either of those things. So what happens to them? Well, some quit, anyway, thanks to who-knows-what quirk of genetics or luck. But some of them keep taking drugs. Because life hurts, and opioids are really good pain relievers—at least, for a while.

I’VE JUST PAINTED A VERY SYMPATHETIC PICTURE of why someone might take—and continue to take—opioids. But it would be irresponsible of me to focus only on cases like mine. Doing so makes possible the response that my exposure to drugs “wasn’t my fault,” which makes me different from other people who take drugs.

So let me say something really clearly: I don’t think I’m any different from other people who take drugs. At least, I’m not morally different from them. You shouldn’t judge me differently. I’m not more sympathetic than “those” people.

WHEN I FINALLY CAME OUT OF WITHDRAWAL, AND BEGAN TO GAIN SOME DISTANCE FROM THE TRAUMA, MY GOOD FORTUNE AND MY PRIVILEGE HAUNTED ME.

At this point, one might object that I was following my doctors’ orders. It’s not like I was taking heroin. I was taking medicine. Other people take drugs. I was treating pain. They are chasing a high.

But it’s just not that simple.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, America was in the grip of its first opioid epi demic. This first one was brought about by the proliferation of morphine use, along with the development of the hypodermic syringe, which delivered the powerful drug straight into the bloodstream and quickly to the central nervous system. As fear of the blooming public-health crisis grew, pharmaceutical companies began the search for the holy grail of pain medicine— a more potent, less addictive opioid.

In 1898, a little company called Friedrich Bayer & Company thought it had found just the thing. Its new wonder drug, heroin, was both an excellent analgesic and a cough suppressant. Furthermore, Bayer told the world, it was nonaddictive. Doctors and pharmacists could rest easy and prescribe heroin for any kind of pain, as well as for restful breathing in patients who had influenza or tuberculosis. Even morphine addic tion could be treated with heroin.

Of course, Bayer was wrong to say that heroin was non-addictive. And by telling doctors, pharmacists, and the public that it was a safe medicine, the company allowed heroin to escalate America’s opioid crisis, and public opinion eventually turned on the drug. In 1914, heroin (and other “narcotics”) was regulated and taxed, and a decade later it was outlawed.

And that is why heroin is illegal today. Not because it’s an evil drug, endlessly seductive and serving no medical purpose. It’s an opioid, similar to morphine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, and the rest. It has the same benefits and risks. And it gives people the same reasons to take it that other opioids do. So if you happen to live in a community where heroin is more affordable than health care, and you’re in pain, it’s not unreasonable to take heroin. Or if you develop an addiction

19 TRAVIS N. RIEDER

to pills, and you’re then cut off by your doctor, heroin can fill the void. In addition, opioids like heroin and oxycodone treat more than just physical pain. Emotional, psychic, and traumatic pain are also dulled by the drug.

When I finally came off the oxycodone, I found myself overwhelmed with grief, mourning the loss of my whole, functioning body. I remember sitting with my mom, laying my head on her shoul der, sobbing, “I’m just so broken, Mom. I’m just so broken.” I thought about not being able to chase my daughter, or play sports with her. I obsessed over the idea that someday she would want to go to Disney World, and I wouldn’t be able to spend a full day walking around the park, let alone carrying her when she eventually spent all her childish energy. My identity as a youthful, athletic dad was crumbling.

Part of the explanation for this onslaught was undoubtedly the psychological effects of the withdrawal; but part of it, too, was that I had been constantly medicating my emotional pain from the moment of the accident. It is no wonder that opioid use is particularly common among those who have experienced trauma, for whom the grief is just too much.

Of course, not everyone who takes drugs is self-medicating; some people really are “just

looking to get high.” And this might seem most objectionable, as an individual is doing something risky (and illegal) for the sake of enjoyment. But, even here, it seems important to note that how attractive drug-induced euphoria seems depends on many factors, including—especially—how good life is without the drug. I was able to endure the suffering of going without the drug only because I had so many good things to look forward to. Not everyone is so fortunate, and I don’t think that patients like me should get moral credit for being lucky.

People take drugs for reasons. I think we forget that a lot. Too often we equate drug use with addiction, and think of addiction as robbing someone of their free will. So we don’t think of people choosing to take drugs.

But the reality is that people do choose to take drugs, and the way those drugs interact with a per son’s brain gives them more reasons to keep taking them. Stories of physical dependence, addiction, and overdose are all stories of multiple tragedies. Tragic because of the pain eventually caused by the drug, and tragic because of the pain the drug was supposed to address.

TRAVIS N. RIEDER, PH.D., is a philosopher and a bioethicist at the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics, whose recent work focuses on the ethical and policy issues raised by pain, opioids, and America’s drug-overdose crisis. In 2019, Travis published In Pain: A Bioethicist’s Personal Struggle with Opioids, which was chosen as one of NPR’s favorite books of the year.

Photograph of a Bayer apothecary pill bottle of Heroin Hydrochloride. © Global Foto Archive.

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER REVIEW20

TO WALK IN CLEAR SKIES

I SAT IN THE RENTAL CAR with my soon-to-be husband as we drove into Salem, past lines of cars waiting to enter overpriced parking lots—their rates tripled and quadrupled for the month of Halloween—and as we drove I started feeling pins and needles on my tongue and at the back of my mouth and down my throat, as if it was all going numb, and I won dered if this was what it felt like to be hanged.

We gave up trying to park and just kept driv ing. We drove north for three miles until we arrived at 39 Hale Street, in Beverly, Massachusetts. We parked the car on the street outside a yellow clap board house. The uncomfortable tingling sensation in my mouth and throat were gone. They’d disap peared as soon as we left Salem’s town center, and now, standing outside this yellow house, I felt comfortable and safe—as if this home were my home. As if here, in the radiating warmth of the autumn sun, beneath the towering green tulip tree, I was completely welcome.

The house belonged to my eighth-great-grand father John Hale, who was the reverend in this town for thirty-three years. He moved to the house just after 1692, after two young girls in the neigh boring village of Salem began exhibiting strange behavior. When he saw the girls, he immediately suspected that witchcraft was to blame and encour aged the creation of the trials. Fifteen months and twenty-four dead bodies later, the Salem witch trials ended.

Throughout the trials, Hale was intimately involved. He was present during examinations of the accused, testified against two women, and counseled the judges and other trial participants,

but in November of 1962, when his wife, Sarah Noyes Hale, was accused, he began doubting everything.

It was in this yellow house, in the years following the trials, that Hale wrote A Modest Enquiry Into the Nature of Witchcraft—the book in which he formally denounced the trials and expressed remorse for the innocent lives that had undoubtedly been taken. He didn’t believe they were innocent because witchcraft wasn’t real. No, he firmly believed in the invisible forces—good and evil. He simply challenged our ability to judge them clearly.

“We walked in the clouds and could not see our way,” Hale wrote. The clouds, he explained, were fear. A fear he knew well, for he’d feared witchcraft for most of his life. In 1648, just twelve days after his twelfth birthday, he watched a woman being hanged for witchcraft. She was the first of fifteen people to be killed in the course of fifteen years, during New England’s first witch hunt, which lasted the entirety of John Hale’s adolescence.

She was accused—among other things—of being psychic, of accurately predicting the future and knowing people’s secrets. Of course, most people today will tell you that she wasn’t really psychic or a witch. None of them were. Because these things are not real.

At least, that’s what I was taught. Unlike my eighth-great-grandfather, I was raised with no religion and no spirituality. I never believed in invisible forces—save for gravity—and because I didn’t believe in magic, I never feared it, and I never looked for it. So you can imagine my surprise

VIRGINIA MASON RICHARDSON

21 VIRGINIA MASON RICHARDSON

Right: Jonathan Corwin House—the Witch House—Salem, Massachusetts. Courtesy of Steven Milne / Alamy Stock Photo.

when I started meditating, when I got really still and listened to myself, and I discovered that magic was the most natural expression of my being.

By magic, I mean that when I cleared my mind of all my thoughts—the ones I’d created and the ones that were created for me—other experiences entered that open space. Visions came through. Knowings. Feelings. Predictions. A connection to something I’d never felt before that was so big and powerful it felt as if it was both me and outside of me, and it seemed to have no name, and it only ever felt like peace and love and truth.

In the past seven years of my life, I—like my eighth-great-grandfather—have become a person of faith, of believing in invisible forces. I receive messages in my dreams that come true. On hundreds of occasions, strangers have sat down in front of me, and I’ve closed my eyes and accurately received information about their lives through visions and sounds and feelings. I regularly wish for things, and they come true. And, often, I’ll be going about my day—folding my laundry, doing the dishes, the most mundane of tasks—when, suddenly, it’s as if I can hear the ocean in my ears, and, if I close my eyes and listen carefully, the waves become words—messages, songs, instruc tions—all full of what I felt in those early days of meditation: peace, love, truth.

John Hale and the other powerful men in Salem thought that experiences like these were an aspect of witchcraft. This, in their minds, was Satan’s work. Because that’s what they’d been taught. And that’s what they feared.

I don’t consider myself a witch in the Christian sense of the word, but I am a woman, having an experience, trusting and following her own inner knowing, and in today’s society—just like in 1692— this is an act of rebellion. I can’t tell you how many people have told me that my experiences couldn’t possibly be real; that, in short, I—in my entirety, as the person I truly am—do not exist.

Disbelief, I think, was perhaps the natural evolution of our fear. Because you can’t fear something you don’t believe in. And I think that, for many of us, the clouds we walk in now, the ones that stop us from seeing clearly, are no longer fear but disbelief. I know, because I walked in them, too, and I’m actually grateful for this, because it meant that when magic showed up I wasn’t afraid, and I could just experience it—without judgment.

As my fiancé and I drove away from John Hale’s yellow house, he was visibly upset. Upset that I’d been so happy there, walking around the yard, taking photos, smiling by the tree. “This is a man who killed many people!” he exclaimed.

I knew it was true. I hadn’t forgotten, and I wondered if perhaps I was able to be so happy because I was rewriting Hale’s story in my mind. Perhaps I was focusing too much on the part where he eventually spoke against the trials rather than on the part where he instigated them and twentyfour people died, and now the energy still feels so heavy in Salem that, driving through, my throat hurts, and, as I thought about all of this, I could feel inside me the blood of the persecutor and the spirit of the persecuted, but then I took a deep breath, and I cleared my mind, and there, in the white rental car, I could still feel what I’d felt beneath the tulip tree: the warmth of the sun on my skin and the truth that John Hale is not judging me. He just loves me.

And, despite all the fear and disbelief we walk in that make us judge one another and kill one another and do all sorts of unspeakable, unloving things, I choose to trust my instincts and the inner knowing that we are all connected, that love moves through us; that, despite what happens when we are here, we return to the earth, and we return to that love, and after enough time has passed that is all that’s left.

A longtime atheist, VIRGINIA MASON RICHARDSON’s life changed completely after a traumatic event opened her to psychic experiences. As she embraced her gifts, she unex pectedly healed three people of chronic illnesses, overcame a cycle of abuse, and discovered that magic is real. She has now committed her life to following her intuition and shar ing what she uncovers. She recently finished writing her first book, a memoir titled Synchronicities, and is working on the sequel.

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER REVIEW22

Right: Howard Street Cemetery, Salem, Massachusetts. Courtesy of MomoFotograFi / Alamy Stock Photo.

I don’t consider myself a witch in the Christian sense of the word, but I am a woman, having an experience, trusting and following her own inner knowing, and in today’s society—just like in 1692— this is an act of rebellion.

Lincoln Center Theater Review

Vivian Beaumont Theater, Inc. 150 West 65 Street New York, New York 10023

NON PROFIT ORG U.S. POSTAGE PAID

NEW YORK, NY PERMIT NO. 9313