National Leadership Roundtable on Church Management

National Leadership Roundtable on Church Management

MANAGING FOR MISSION: B UILDING STRATEGIC COLLABORATIONS TO STRENGTHEN THE CHURCH

2012 Annual Meeting | Georgetown University | June 27-28, 2012 www.TheLeadershipRoundtable.org/2012AnnualMeeting

5 Opening Prayer

5 Welcome and Introduction

Kerry Robinson, Executive Director, The Leadership Roundtable

6 Leadership Roundtable Year in Review

Kerry Robinson, Rev. Paul Holmes, Geoffrey Boisi, B.J. Cassin

17 Observations from a Lifetime of Land Navigation

James Dubik, Lt. Gen. (Ret.), US Army

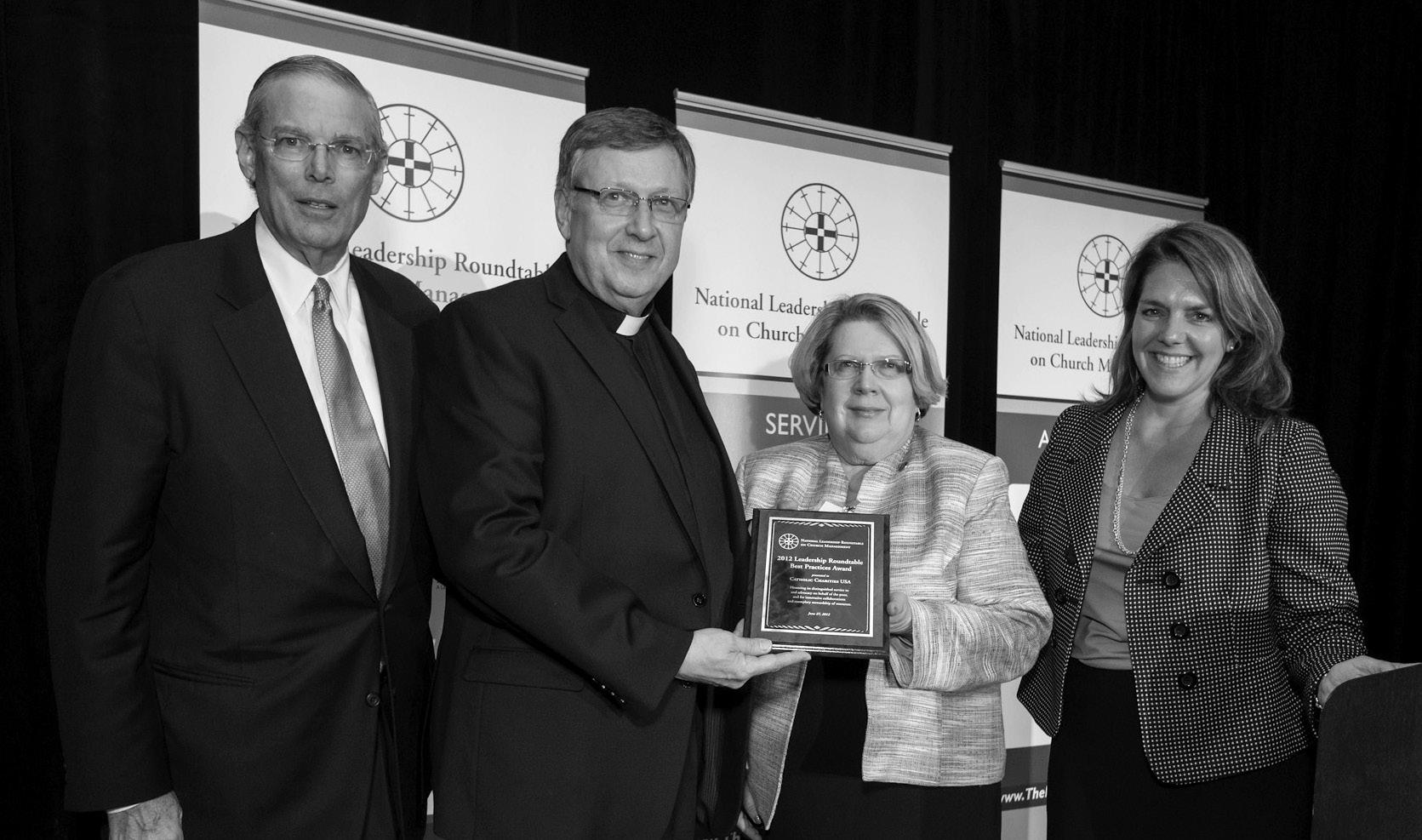

25 2012 Leadership Roundtable Best Practices Awards

33 Partnership: An Inevitability

Carolyn Woo, President and CEO, Catholic Relief Services

37 Connecting with Today’s Funders: Observations from an Investor Charles Harris, Founder, SeaChange Capital Partners

45 The Era of Assumed Virtue is Over: The New Normal Robert Ottenhoff, President and CEO, GuideStar

51 Strategic Collaborations to Strengthen the Church

Dennis Cheesebrow, President, TeamWorks, Int’l.

57 Appendix 1- 2012 Annual Meeting Presenter and Facilitator Biographies

59 Appendix 2- 2012 Annual Meeting Participant Biographies

63 Appendix 3- Publications

This publication is a collection of the wisdom, insights, observations, and exchange of ideas from participants at Managing for Mission: Building Strategic Collaborations to Strengthen the Church.

In June 2012 the National Leadership Roundtable on Church Management convened leaders from the Church and secular fields at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., to address contemporary challenges facing the Catholic Church and to consider a set of questions related to partnership and collaboration. Included in this book are excerpts from the panels and presentations, as well as selected questions, answers, and insights from a wide range of Annual Meeting participants.

You are encouraged to learn more and continue the conversation online. Visit www.TheLeadershipRoundtable.org/2012AnnualMeeting for on-demand video presentations of all speakers and panelists, an electronic copy of this publication, as well as supplemental materials including the mirco-biographies of all participants, a detailed agenda, and other information pertinent to the meeting.

To join the continuing conversation, visit the Catholic Standards for Excellence Online Forum at www.CatholicStandardsForum.org where workgroup findings are posted and updated.

MANAGING FOR MISSION: BUILDING STRATEGIC COLLABORATIONS TO STRENGTHEN THE CHURCH COPYRIGHT 2012 THE NATIONAL LEADERSHIP ROUNDTABLE ON CHURCH MANAGEMENT. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

MICHAEL O’LOUGHLIN, EDITOR. PATRICK MCCLAIN, KATHARINE MCKENNA, AND KEVIN WATSON, EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, PLEASE EMAIL INFO@NLRCM.ORG OR CALL (202) 223-8962.

Professor of Sociology and Religious Studies, Emmanuel College

Loving God, we come to you today in prayer to ask for wisdom, strength, and courage as we face multiple challenges in our Church, in our country, and in our world. Bless, in a particular way, our deliberations here today and tomorrow. We seek to hear your word, to follow your truth, and to minister in your name to all who need your love and care, particularly your beloved poor. We ask this in the name of our brother and Lord, Jesus Christ. Amen.

Kerry Robinson Executive Director, National Leadership Roundtable on Church Management

We have two purposes for gathering annually. The first is that we want to give a proper account of the services that we have developed and the programs that we have put in place to respond to the temporal challenges facing Church leaders in the United States. So it is our way of being accountable to our members and showing you how we are properly utilizing your intellectual contributions to our mission. Our second purpose is to highlight a particular opportunity or challenge facing the Church and to bring brilliant men and women—ordained, religious, and lay—together to explore those challenges and come up with effective responses to meet the temporal challenges that we have identified.

In the past, this gathering has taken up such matters as the financial and managerial considerations of organizing a diocese, a parish, or a Catholic nonprofit. We have focused on management, human resource development for the Church, and communications. Two years ago, we took up twin challenges at the time. We examined the ongoing sexual abuse crisis that Europe was experiencing, showcasing some of the

fine work that has been done in this country to respond to it as a way of being helpful to our global Church. And we discussed the crisis of the global economic meltdown and how that impacts the health of the Church. Last year we were prevailed upon by bishops and our own members to take up the subject of parochial school systems, specifically to convene experts in the field of Catholic education to focus on the long-term sustainability and health of Catholic school systems, and that resulted in a series of recommendations that we have fine-tuned and are working on now; you will hear some more about that later this afternoon.

This year, of course, our topic is the importance of strategic alliances and partnerships. And the genesis of this, frankly, was the members of the Leadership Roundtable who represent Catholic philanthropic foundations and who are Catholic philanthropists themselves. Since Vatican II, in this country, a number of very prominent Catholic families have been supporting, financially, the creation of Catholic national networks whose own mission has a bearing on ours. They are important life-

giving networks and apostolates to the life of the Church. How you navigate a changing world and allow yourself to be open to risk-taking and strategic alliances for the sake of your own financial sustainability was key in the formulation of our gathering today. And as you see, we have a stellar lineup of keynotes and a set of working sessions, which allows us to capitalize on the fact that any one of you is a keynote in his or her own right. And we will be working you very hard tomorrow for the sake of the common good of the Church.

Kerry Robinson Executive Director, National Leadership Roundtable on Church Management

And now I would like to turn to the first purpose of our meeting, which is a report and account of the work of the Leadership Roundtable. To help me do this, I have three extraordinary men with me, all personal heroes of mine.

The first is Fr. Paul Holmes, who is professor of moral and sacramental theology at Seton Hall University and was the first vice president for mission at the University. It has been a great privilege for the Leadership Roundtable to partner with Seton Hall University and specifically with Fr. Paul Holmes in creating the Toolbox for Pastoral Management, which is offered in a retreat-like setting for six days to new pastors. Bishops from all over the country are sending their priests to this wonderful opportunity.

Next to him is Geoff Boisi, the chairman and CEO of Roundtable Investment Partners, and most importantly, the founder of the National Leadership Roundtable on Church Management. His leadership, passion, and commitment to the Church, and specifically to the Leadership Roundtable, as a way to be part of the solution is inspiring, and we owe a profound debt of gratitude to him.

And next is B.J. Cassin, chairman and president of Cassin Educational Initiative Foundation. He was formally welcomed onto the board of trustees of the Leadership Roundtable today. He is also the chair of the board of the Cristo Rey Network.

The first thing that I would like to point out to you is, in your packets you have received, hot off the press, our 2012 Annual Report. Our communications manager, Mike O’Loughlin, is responsible for this. It reflects, particularly on the inside, our commitment to measuring the impact and reach, the breadth and depth, of our work on behalf of the Church. We are using this as a baseline, but in every subsequent quarter and year, we will add to this to document where our presence is having a positive impact. Right now we are present in 96 dioceses. We also work with religious orders, men’s and women’s, with national Catholic organizations, and, of course, hospitals, schools, universities, and charities. We take metrics very seriously, and while it’s not always easy to measure the impact that we are making, we are detailing, in a very deliberate way, where we have a presence. What I can assure you is that the demand for what we are offering the Church is growing, and it is our task as a board and as members to manage that in a way that does not sacrifice quality and allows us to be even more beneficial to the Church we love.

Our Catholic Standards for Excellence online forum is a free, interactive online chat room, essentially, and it also provides for the exchange of best practices in the temporal affairs of the Church. We

are using the Forum over the course of these two days. In our breakout sessions, the scribes will be uploading some key insights onto the site. Over the coming days, weeks, and months, we will have an opportunity as participants to go back to the Forum to refine some of the practices, ideas, and suggestions that are offered over the next two days.

As you know, our mission is to promote excellence and best practices in the management, finances, human resource development, and communications of the Catholic Church in the US, with a particular focus on greater incorporation of the expertise of the laity. You have heard me, many times, note that the Catholic laity have risen to levels of affluence and influence, and count among the highest echelons of leadership across every sector and industry in the United States. We would be failing in our basic Christian stewardship if we were not, as a Church, to avail ourselves of that talent and expertise. This is why, ladies and gentlemen, you have been invited here today, and I am so grateful to you.

“ As you know, our mission is to promote excellence in best practices, in the management, finances, human resource development, and communications of the Catholic Church in the US, with a particular focus on greater incorporation of the expertise of the laity.”

In March of this year, anticipating our seventh anniversary on July 11th, next month, we took stock of all that the Leadership Roundtable, with your support, has created to respond to temporal challenges facing the Church. And we took a deep breath and marveled at what we had, in fact, created. Then we acknowledged that the Leadership Roundtable is no longer an experiment, but is, in fact, a very important resource in service to the Church, particularly because of its laser focus on temporal challenges. It avoids the neuralgic issues that tend to divide and separate Catholics, and we harness what we do best, which is to strengthen the management, finance, and human resource development of the Church. And with the confidence that we were on to a great thing and had something wonderful to continue to offer the Church, we unveiled our vision for the next few years, and that includes strengthening our offering in four areas, which my fellow panelists will be addressing.

1. The first column is what we have always done; namely, to develop specific solutions to the challenges that keep Church leaders up at night. This column includes all of our signature services and programs.

2. The second column is a focus on identifying the top 50 families,

foundations, and individuals who are committed in a very serious philanthropic way to supporting the Catholic Church. We want to identify these 50 by region. There’s increasing demand, so we need resources in order to disseminate our programs properly across the country. We recognize that there is something profoundly important about the intersection of Catholic financial capital and Catholic intellectual capital, and when you bring those two together, you create a lay force to be reckoned with that is profoundly faithful and profoundly effective. We don’t just want to identify these top 50 families and individuals to support the Leadership Roundtable, though, because we know that with their experience of philanthropy comes a great experience and bird’s eye views of some of the important needs facing the Church.

3. The third column is the Leadership Roundtable schools initiative. B.J. will be addressing that later this afternoon to update you on how the Leadership Roundtable can take its particular area of expertise and lend that in service to the challenge that all Church leaders are facing with respect to the long-term sustainability and health of Catholic parochial school systems.

4. And the fourth column is an investment initiative that Geoff Boisi will explain. The idea came out of a conversation in 2008 at the start of the economic crisis from a conversation that Geoff and I had

with Cardinal George, who was then the president of the US Bishop’s Conference. Cardinal George asked the Leadership Roundtable specifically for assistance in helping bishops safeguard and strengthen Church assets in an uncertain economic period. One of five suggestions that we have developed for the bishops and other Church leaders to consider is the idea of strategic investing.

Distinguished University Professor of Servant Leadership, Seton Hall University Program Coordinator, The Toolbox for Pastoral Management

This is my first time at a Leadership Roundtable Annual Meeting. I’ve been working with the Leadership Roundtable for three years and I’m very, very excited to be with you. I have an announcement that I should make before I begin. I am the happiest priest you will ever meet. I know there are my brother priests in

the audience, but I’m sorry. This position is taken, and it is mine. Why am I the happiest priest you’ll ever want to meet?

Well, I only have 10 minutes, so I can’t tell you everything. What I can tell you is this: there are few things as rewarding as working on a project harder than you’ve worked on anything and having it turn out to be a magnificent way to help one’s brother priests. The Toolbox for Pastoral Management is that for me.

We bring in 15 experts and invite 30 priests for a week in a retreat-like setting. There’s morning prayer, evening prayer, and the celebration of the Eucharist. We have adoration of the Blessed Sacrament and confessions. But in the midst of all of that, the priests participate in 15 presentations, which are very, very interactive. We bring these experts in from all over the country on subjects as varied as internal financial controls, risk management, working with your parish business office, a mission-driven parish, Christian stewardship, human resources 101, building councils, a six-month game plan for a new pastor, Standards for Excellence, creating an evangelizing parish, and a theology of management. These 30 priests, who have just been named pastor, are as nervous about that new identity as

you can imagine. At the end of this week, they feel much more comfortable.

This is what happened. Back in 2006, Tom Healey, the treasurer of the Leadership Roundtable, visited Seton Hall and asked our president, “Can Seton Hall create an executive education experience for new Catholic pastors and give them the administrative skills that they aren’t taught in seminary but skills they’ll need to be successful pastoral leaders in the 21st century?” We said yes, and I worked with Tom Healey, and with the Leadership Roundtable’s John Eriksen, Michael Brough, Jim Lundholm-Eades, Kerry Robinson, and other dedicated members.

contacted me is because there isn’t even room at the retreat center. Otherwise, I might start just putting up cots on the beach, because there’s a great deal of excitement that we learn about through emails and telephone calls. This Toolbox in July has 38 priests from 18 different dioceses, and it includes a Canadian and even an Armenian. This is the first time we’ve had someone from one of our sister Eastern Churches.

Since Tom Healey’s first meeting at Seton Hall six years ago, we have edited the 15 Toolbox presentations and submitted them to a publisher so that there might one day be an easy-to-read how-to manual

“ ese 30 priests, who have just been named pastor, are as nervous about that new identity as you can imagine. At the end of this week, they feel much more comfortable.”

We came up with 70 potential learning outcomes. What would we want our new pastors to know at the end of this week? And we started small. We thought, “Let’s start with region three, New Jersey and Pennsylvania.” As it turned out, by the time we opened our first Toolbox, we had new pastors not only from Newark, Patterson, Camden, and Metuchen, NJ, and Allentown and Harrisburg, PA, but because of the great deal of work done by the Leadership Roundtable, we had men from as far away as New Orleans, Houston, and St. Petersburg, FL.

And today, four years later, we are about two weeks away from our fifth Toolbox for Pastoral Management. We’re oversubscribed, which is a wonderful thing. The only reason I’ve started to say no to some of the priests who have

for new pastors. We wrote a proposal to Lilly Endowment, Inc., who so loved it that they provided a very generous grant that has allowed us to do two Toolboxes a year and to take the Toolbox on the road. We meet not just at the Jersey Shore, but are able to bring the Toolbox to various places in the country. Our first such non-New Jersey toolbox was held last January in Jacksonville, FL. Bishop Estevez and

“

allows the learning that takes place at the Toolbox to continue and turn into lifelong learning. ”

the Diocese of St. Augustine were so hospitable I considered incardinating into his diocese.

What makes the Toolbox different and, I daresay, better than other new pastor workshops is CatholicPastor.org, an online virtual community of practice that allows priests from all over the country to share best practices and creative ideas of all kinds. It’s maintained by Fr. Frank Donio, SAC, and Alex Boucher, who are here with us today. It’s modeled on what Lt. Gen. (Ret.) Jim Dubik of the Leadership Roundtable helped create for Army captains in Iraq, allowing captains all over Iraq to talk to one another without their bosses listening in, and talking about what they’re finding difficult as captains, and ask candidly, Does somebody know a better way? CatholicPastor.org is doing the same for priests all over America. It allows the learning that takes place at the Toolbox to continue and turn into lifelong learning. And as a professor, I’m very, very excited about that.

“ We also observed that if we could start to pool the resources of some of the major philanthropic leaders of our country who were devoted to Catholic activities, we could maximize impact and effectiveness of the programs that we all support.”

for Pastoral Management is a huge, unmitigated, flabbergasting success. That’s the only kind of thing I like to be involved with. By the end of July, when we have our fifth Toolbox, we will have offered the Toolbox to 143 pastors from 38 dioceses and brought over 30 expert presenters from nearly 20 different dioceses around the country. And we’ve begun work with Seton Hall’s technology experts to convert our 15 face-to-face presentations into online self-paced modules which can reach the other 35,000 priests in the United States.

Geoffrey Boisi Chair and CEO, Roundtable Investment Partners, LLC Chair, National Leadership Roundtable on Church Management

vision of the providers of capital and the users of capital. We observe the same thing in the Catholic community. And we thought that a smart thing for us to do would be to bring a group of philanthropic leaders together for the purpose of coordination and synchronization, and exposing their strategic vision as to what was important to the Catholic Church in the United States.

In addition, we have submitted everything to an external assessment consultant who was given free rein to survey the participants from the first four Toolboxes, fly in a group of them to Chicago for a full-day forum, do a structured telephone interview with a randomly selected cohort of Toolbox graduates, and write a formal assessment of all of our work.

I will try to remain as humble as possible, but it turns out that the Toolbox

Let me offer a couple of thoughts on the Catholic Philanthropic Leadership Consortium. My 93-year-old father, a devout Catholic, lawyer, businessman, taught me years ago the two definitions of the golden rule. The first he said, is to love thy neighbor as yourself. The second, he said, he who has the gold rules.

Those of us who have been active in philanthropy have observed over the last number of years that there has been a disconnect between the strategy and

We also observed that if we could start to pool the resources of some of the major philanthropic leaders of our country who were devoted to Catholic activities, we could maximize impact and effectiveness of the programs that we all support. We want to develop a forum where we can develop focused agreement on what defines success in these various programs. We want to develop accountability for results, and effective, efficient use of the scarce capital that’s out there. The ultimate goal is to have, initially, 50 families—I’d like to see us

ultimately get to 100 families— and to have representation in each of the 15 regions around the country.

By developing this sort of strategic think-tank, we will develop greater communication between the philanthropists and then the program developers. And that, essentially, is the concept behind the Consortium. But it will also ingrain the notion of investment, not just giving, but investment into the strategic initiatives that we believe can move the dial for the Church’s mission in the US. We have started to reach out and have received very, very positive reaction from some of the major families in the country already, and we’re looking forward to our first meeting in September.

B.J. Cassin

President, Cassin Educational Initiative Foundation Trustee, National Leadership Roundtable on Church Management

As Kerry indicated, some bishops asked the Leadership Roundtable to convene a meeting relative to Catholic schools. And those of you who attended last year, From Aspirations to Action: Solutions for

“ But it will also ingrain the notion of investment, not just giving, but investment into the strategic initiatives that we believe can move the dial for the Church’s mission in the US.”

America’s Catholic Schools, it was a very lively group of discussions that we had, out of which came 92 aspirations. It’s taken some time putting together some stakeholders to boil those down to what is realistic and what is the most effective way that the Leadership Roundtable, with its resources, would be able to implement. So it went from 92 down to 20, then down to 8 that were presented to the Leadership Roundtable board in March, which they approved. We’re in the process now of actually pulling together business plans on 6 of those, getting the proper staff in place and the proper financial resources so these can, in fact, become actions. John Eriksen will rejoin the Leadership Roundtable this summer, and he will be leading this effort from the staff standpoint.

In terms of the investment partnership that we’ve been developing, the average US household saw that its net worth fell approximately 40 percent from 2007 to 2010. Three out of 5 parishes report that their parish income declined as a result

of the economic crisis. Forty percent of parish leaders report that the current financial health of their parish is tight, but barely manageable. And that’s up from 9 percent only 5 years ago.

In general, churches in the United States saw their contributions drop by $1.2 billion in 2010, up from a drop of $431 million in 2009. So you can see the increase in the financial stress. Eighty-five percent of nonprofits in the US saw an increase in demand for their services in 2011, and 57 percent of nonprofits have three months or less cash on hand. And if that’s not enough, total membership in the 25 largest churches has decreased. The Catholic Church, even though we’ve had tremendous buoyancy from the Latino community, still as a Church, membership has dropped over half of a percent, and that’s a big number when you consider 65 million people.

As a result of that, over the last two years we’ve been working very hard with a couple of other organizations to put together an organized investment partnership. What we’re trying to do is accomplish a little bit what the Carnegie Foundation, Yale University, Harvard, and some of the other major institutions have done in pooling together capital.

This happens to be the 100th anniversary of Andrew Carnegie taking $100 million in 1911 and investing it. For the first 75 years, all they did was put that in bonds. They lost purchasing power during that period of time. In the early 1970s, they started to go to a 60 percent/40 percent weighting of stocks to bonds. And they got it up to $187 million in the early 1980s. But then they started to use sophisticated investment asset allocation, going after and identifying best of breed money

“ Our objectives were to develop a program that would assist the financial stability of the Catholic Church; to successfully execute its mission through more professional, sophisticated, productive management of its capital base on a national basis; and create a world-class investment management partnership among Catholic affinity groups and individuals with consistent top-tier performance that commands the respect of all.”

managers around the world. They grew that $187 million to close to $2.7 billion today, after investing an additional $2.6 billion over that period of time in grants. And that, basically, was by compounding, leaving the capital in and compounding it by approximately 10 percent a year over that 25- to 30-year period of time.

We thought that this approach would be particularly attractive for the Catholic community, as it has been for Episcopalians, Lutherans, and some Jewish communities. We’ve been working with a few other organizations to identify a program that could achieve similar results to these major institutions for the Catholic Church. If we could perform anywhere near like those organizations, the Church would be utilizing its capital at 500 to 600 basis points annually better than that 60/40 kind of allocation.

Our objectives were to develop a program that would assist the financial stability of the Catholic Church; to successfully execute its mission through more professional, sophisticated, productive management of its capital base on a national basis; and create a world-class investment management partnership among Catholic affinity groups and individuals with consistent top-tier performance that commands the respect of all.

We would accomplish this through the utilization of a more nuanced approach to Catholic socially responsible investment principles, providing a spectrum of socially responsible investment principles for all the organizations given their level of discipline that they want to apply to SRI investment; develop a brand recognition for excellence and trust through the attraction and development of the highest quality talent; and utilization of the most sophisticated investment solutions that are responsive to client needs and offered on a cost-effective basis.

By pooling capital together, we can get performance up and costs down, and then become the investment option of choice for the Catholic market.

We’re very hopeful that, within the next couple of months, we’ll be coming forth to the market with a significant amount of capital to achieve this goal. And we think it can make a major contribution to the Church in the US.

Patrick Carolan

Executive Director Franciscan Action Network

My organization does a lot of work on social justice issues, such as immigration reform. We discovered there is a lot of money that’s invested by faith-based organizations in private prisons. So I’m wondering, how are you going to balance a good return on the money with the concerns of the Church? Have you reached out to people like Sr. Nora Nash or Fr. Michael Crosby who have done a tremendous amount of work in this area of social investing and investing based on Catholic social teachings?

Geoffrey Boisi

This is a very important issue and one we’re addressing with Christian Brothers Investment Services, who have been a leader in the area of socially responsible investing, and we’ve also reached out to other institutions, Catholic institutions, and, frankly, there are some that are extremely interested and disciplined in their SRI investing. What we want to do in developing this is to create a menu of

options for people. Anything that goes into a pooled vehicle will be scrutinized and we’ve been working with a variety of organizations to make sure that we are scrupulous to avoid the kinds of things that you were talking about. One of the reasons why we want to work with the Christian Brothers is the work that they’ve done in this area. But there are other Catholic Institutions that have a different perspective and we think that there needs to be a spectrum of options for everybody within the community.

Joan Neal

Vice President of Institutional Planning and Effectiveness, Cabrini College

Is there a list of the investment advisors and managers, and could you talk a little bit about the screen that you apply to the selection of these managers?

Geoffrey Boisi

We’re in the midst of developing all of this. As you can tell, it’s a very complex formulation to put this together, to make it work. We’ve been interviewing a number of different screening organizations to look

at the different issues that are Catholic related to make sure that we are not investing in anything that is inappropriate. We’ve been working with Christian Brothers at one end of the spectrum, and, as we go down that path, there is what I would call a slightly more nuanced approach to it, where if any organization has less than 3 percent of revenues or if 3 percent of the overall portfolio was in something that might be potentially neuralgic, it would get kicked out. We’ve developed multiple screens that would be utilized several times each year to ensure that there is a scrupulous approach to making sure any inappropriate investment was discontinued.

Fred Fosnacht Founder

My Catholic Voice

Have you determined the criteria for participation?

Geoffrey Boisi

The hope is to create a situation where at the parish level, at the Catholic nonprofit organization level, and the diocesan level,

that you can have as little as $250,000 to $1 million of participation. You would control those assets, but they would be pooled with other capital of larger organizations. You know, there is some capital that could be invested over a long period of time, and that would have private equity transactions, alternative investments, and that sort of thing, but it would have to stay in that pool for at least a three-year period of time. There will be another pool of capital that would provide either monthly or quarterly liquidity. There will be another pool of capital that has even shorter-term liquidity. And we’re also hoping to have a set of capabilities that could be done by asset class as well.

We’re working through this with the accountants and the lawyers now to create these pools so that we can make sure that everybody receives the correct proportion of return on their investments but with the benefits of being part of a large pool, giving them access to managers who serve institutions such as Harvard, Yale, and the Carnegie Corporation. We hope that the entry level is a modest amount of capital, so that an individual parish that wants to invest $1 million, that would never have the opportunity to invest with the kind of money managers that Notre Dame, Boston College, Georgetown, or Harvard and Yale retain, would now have that access.

Rev. John Hurley, CSP

Executive

Director

Department of Evangelization

Archdiocese of Baltimore

I want to thank the Leadership Roundtable trustees. Paul Henderson and I both serve as co-chairs for the Mid-Atlantic Congress, and it was a tremendous success last year. It is sponsored by the Association of Catholic Publishers and the Archdiocese of

Baltimore. We drew people last year from 65 dioceses and over 1,400 participants for the first time. We had a very positive experience with the Leadership Roundtable.

So as we look at next year, Michael Brough has been excellent in being a part of our planning committee to have a diocesan leader track and a parish track. Archbishop Lori responded to Kerry’s invitation about having a bishops-only possibility at the conference as well, so I want to thank the Leadership Roundtable for its efforts. I think we’re looking at this as Catholic leaders coming together and how we can celebrate and recognize the best practices among us. And I think you’ve been a key part of that. So, on behalf of the Association of Catholic Publishers and the Archdiocese of Baltimore, thank you.

James Donahue President Graduate Theological Union

Has there been any consideration about incorporating aspects of the Toolbox for Pastoral Management into seminary training?

We’ve had many discussions about this. I was on the faculty of the North American College in Rome in 2000, teaching young men how to preach. My archbishop would only release me for a year, so at the end of that year, it is the practice at the college to have the entire faculty and staff meet for an entire week, and invite the new faculty and administrative members who are going to be joining them in September to fly out to Rome for this meeting. The rector, who was Msgr. Timothy Dolan at the time, said, “Paul, you’re here and you’re leaving, so you can say anything you want, and you don’t have to worry about how we’re going to react to it. Is there something that we don’t do that we should be doing?” I said, “You know, we send men home to be pastors, and they don’t know how to hire, fire; they don’t know how to do any of the things that they’re eventually going to have to do.”

When I was ordained 31 years ago, I was told, in Newark, that I wouldn’t be a pastor for 27 years. Men are becoming pastors the day after their ordination today. So, while I would have had three pastors, at least, as an apprenticeship before becoming a pastor back then, new pastors today, whatever their age, are walking into parishes with no training whatsoever in the very skills that they need to be effective pastoral leaders and to bring the people to Christ. So I told that to Msgr. Dolan.

We have the largest seminary in the US at Seton Hall, and I’ve spoken to the rector there. The difficulty, at least with Catholic seminaries, is that there is a very

full program for priestly formation for all Catholic seminaries. There is no more room in a schedule with all the things that seminarians are required to learn. This is shocking. I mean, there’s no room to teach them how to do the things we want them to do. So it would be very difficult to insert opportunities for seminarians to gain these skills. And I’ve accepted that as just a reality that we can all be unhappy with, but at least the Toolbox for Pastoral Management comes in and tries to do what’s missing.

We offer a week to new pastors. Certainly, isn’t there a week in a seminarian’s life over the course of four years, and hopefully close to his ordination, when we could do a week for them, too?

I really appreciate your question, too, because it illustrates a cardinal virtue of the Leadership Roundtable. The first place we went with the Toolbox idea was to the seminaries. It’s the obvious place. We respected their “no,” which is to say they were already full, but we didn’t let that stop us from meeting the unmet need. And really, the Toolbox for Pastoral Management was created to get past that “no.” And what I see happening is seminaries are starting to come to Fr. Paul and say, “Could we maybe introduce the Standards for Excellence somewhere in our curriculum?” So we never give up.

I was just reading the magazine that comes out four times a year from the North American College. On one of its pages it describes experiences

during their pastoral education where seminarians discuss temporal administration of a parish. And this is the first time I’ve seen any notice of it. It’s sitting on my coffee table. I plan on writing a note to the rector and saying, “Good for you.” It’s important for them.

Probably, though, the real answer is that we ought to be identifying lay people who are actually trained and qualified to do that kind of work and give the priests enough background so they can communicate, but the lay professional should be exercising more responsibility in this area.

One of the things we train these new pastors in is, “You are not the messiah. You can’t do all of this. You are going to have to rely on your brothers and sisters in Christ to do their work in building up the Church and helping you manage your parish.”

Provincial Minister Province of St. Joseph of the Capuchin Order

I want to encourage you to push back and try to get that into the seminary curriculum. I was named a pastor of a parish in Chicago two weeks after I was ordained in 1993, and I had to learn everything on the fly. I think there are places in the curriculum in the seminary program, even if you’re following the program for priestly formation, to include these things. Where there’s a will, there’s a way. I think we have to find a way, because I think we really harm a lot of young priests and discourage them by not teaching these skills. When you look at a lot of the data that’s coming out of CARA and places like that, it shows how many priests leave within the first 5 years of ordination. A large part of it is because they’re thrown into these situations where they’re overwhelmed with administrative tasks. Even the old guys in our province who have been pastors multiple times, they will say 5 masses a day until they die, but they never want to be administrators again. They say, “That’s not why I was ordained.” But some of us don’t have a choice. If you’re in a parish that has a small budget, you can’t hire all these people to do your work, so you got to find a way to do it.

William Cahoy Dean

St. John’s School of Theology and Seminary

I think the resistance comes not just from the program for priestly formation but also from students, faculty, and staff. The students will say this is the last thing they’re interested in when they’re in seminary, but when they’re out two years they say, “I was not well-prepared.” These ideas always need a champion in the system, and if there’s some way to get faculty involved in things like this, to appreciate the value of it, you’d have an internal champion who might help to make it happen.

Rev. Mr. John Kerrigan

CFO, Santa Clara University

Deacon, Catholic Community at Stanford University

Are there programs here in the US, whether they’re private-to-private, or private-to-public, or outright public

programs, that really excite you and have the potential to be models and drivers for improving the chances of the survivability of Catholic schools, whether broadly or particularly in the inner city?

No matter who gets elected as president, tax reform will undoubtedly be something that’s on the table, and doing the appropriate lobbying to get support of tax credits will be essential. My own personal experience, the Jesuit Nativity School here in Washington, DC, receives about $800,000 from vouchers. The Cleveland Cristo Rey High School and the Tucson Cristo Rey High School, to name two, receive $900,000 to $1 million from the tax credits that the students are able to bring in. So it’s a significant needle mover.

Training is another area where there is need. There are superintendents of schools at various archdioceses who are there for two years, three years, or four years. And there is a need for comprehensive training programs for them, perhaps similar to the Toolbox for Pastoral Management.

The National Leadership Roundtable on Church Management MANAGING FOR MISSION: B UILDING STRATEGIC COLLABORATIONS TO STRENGTHEN THE CHURCH

2012 Annual Meeting | Georgetown University | June 27-28, 2012 www.TheLeadershipRoundtable.org/2012AnnualMeeting

James Dubik

Lt. Gen. (Ret.), US Army Trustee, National Leadership Roundtable on Church Management

As I was thinking about the themes of this conference, adopting structures that will serve us in the twenty-first century, renewing managerial practices, and collaboration, the thing that kept coming back to my mind was land navigation. And I thought, boy, that is really weird. Why am I having these memories of land navigation? But I stuck with it, and I hope by the end of my few minutes that you will come to realize why this stuck in my mind.

Panama

I was a brand-new lieutenant in the early 1970s, and I parachuted into Panama with four hundred other guys. We jumped into

a jungle clearing, and we were supposed to link up on the side of the drop zone and then infiltrate from the drop zone in small groups to a place where we were going to practice some kind of raid on an enemy facility. The jump went fine, we had very few injuries, and most of us landed on the drop zone. We all linked up together, and we broke down in our little groups and took off. As a junior officer, I was assigned with two other junior officers as one of the three people on the navigation team for our group. Of course, our group included the battalion commander and several other senior leaders, so we were a little nervous.

It was nighttime. Nothing really interesting in the Army happens during the day. So we jumped in at night, and I should say that it was so dark that sometimes, literally, you had to hold onto the person in front of you. I don’t mean that figuratively. I mean grab the equipment of the person in front of you so you could follow where that person went.

So we set off. Since this was 1974 or 1975, there were no night vision goggles, so we couldn’t see anything. There were no global positioning systems. And the way you move through the jungle most of the time is you throw your body against the jungle. You back up, take two steps forward, throw your body against the jungle, and you do this for many, many hours. It’s very tiring.

After 7 or 8 hours of doing this we were supposed to have been at a river. We were not. And not only were we not at a river, we were at a swamp. And it wasn’t one of those swamps that precedes a river.

So we sat down, and one of the other members of the group said, “I’ll go forward.” So he goes forward into the night, and all you hear is squishing sounds and then, after a few seconds, “Pull me out!” So the two of us crawl out on our stomachs. We grab him; we pull him out. And now we’re sitting. What the heck are we going to do? Our plan was to use

something called the box method. This is an example where theory and practice don’t match, but this is the theory: you go 90 steps this way until you pass the swamp, then you turn 90 degrees until you pass the swamp. You keep track of the number of steps. Then you turn 90 degrees, keep track of the number of steps. And theoretically, you’re on the other side of the swamp.

So we’re figuring this out, these three lieutenants and I, and the battalion commander is unhappy with how long his lieutenants are taking in leading the team. We can hear him thrashing through the jungle trying to get to us: thrash, thrash, thrash, thrash. And he sits down. He says, “What are you guys doing?” Trying to yell, but whispering at the same time. We say, “Well, sir, we hit a swamp.” “No kidding. This is the jungle. There are swamps everywhere. Just go forward. Follow me.”

And about two seconds later it’s, “Hey, pull me out.”

So two of us go back. We pull him out. Then he says, “Let’s go around it.” “Good idea, sir. We’re going to go around it.”

So we did this. We took the 90 degrees, we counted our steps, throwing ourselves against the jungle for another three hours. And we ended up at 90-90-90, and we were really lost then. The sun came up. We had been walking all night, and we were nowhere near where we were supposed to be. In fact, it took us another day and night to get where we were supposed to be the first night.

Now, we all had maps and compasses. And while it was a funny story, we were all pretty experienced navigators. But at nighttime in the jungle, the map is nearly useless, because you can’t see the terrain features and then identify the terrain fea -

tures to the map to know where you are. Hold that thought.

Let’s fast-forward 18 years. I’m a colonel, and I’m leading a brigade combat team into Haiti in 1994 to reseat President Aristide and his government. And my unit was inserted on a partially finished airfield in northern Haiti where my headquarters would be, and then we were going to be responsible for reseating the government in northern Haiti. We had great maps, I’m happy to report, on this one. They showed all the terrain features, where the little villages were, where the roads, the bridges, where the mountains were. And this time, we were inserted during the day. So we even knew where we were, and we had no trouble, you know, getting around. But we still had this huge navigation problem. The maps that we were given didn’t show the terrain that we really needed to understand to accomplish our mission. The physical and geographic features didn’t matter. They were important, but they were much less important. What we needed to know was social, political, cultural, and religious kinds of questions. Who opposed Aristide? Who supported Cedras? Who was provoking all the violence that we came to stop? Who were the Aristide supporters that we could maybe count on?

You would think that before we went into Haiti we would have had those answers, but we did not. There were two weeks from the time that my brigade combat team was alerted to the time that I was sitting in Haiti wondering all these things.

And now fast-forward 13 more years to 2007. I’m now a three-star general sent to Iraq with Ambassador Crocker and General Petraeus to execute the change in policy that is commonly known as “the

surge.” I arrived there in May of 2007, about three months prior to the height of the violence, and the violence was pretty high. And all the headlines in the newspapers in the spring of 2007 were negative. It was inevitable that we were going to lose, that we were going to be thrown out of the country, that we would have an ignominious withdrawal of US forces, the first in a long, long time. The counteroffensive that had begun had shown no signs of progress in the summer of 2007 and we weren’t sure how things were going to turn out at all.

The job of the organization that I was put in charge of was at this time to accelerate the growth of the Iraqi army and police forces in not just size, but in capability and in confidence so that when the coalition’s counteroffensive was completed they could handle the security in their country and we could leave. The task was to create and expand these forces and the ministries of defense and interior, because that’s how you build a self-sustaining force. This was while the war was going on, before we knew who was going to win, at the height of sectarian violence, and before Prime Minister Maliki really formed a government.

You know, there’s that old commercial of building an aircraft while in flight. Well, our aircraft was not only being built in flight, it was being shot at while it was being built and flown and crewed by people who had never done that before. So the issue at hand here was the plan that we had inherited was just flat not working. The security forces were not growing. In some parts of the country they refused to leave their home provinces. In some parts of the country they refused to fight. In other parts they were in collusion with the insurgents, whether Sunni or other sectarian militias. And we needed a new plan, and we needed a new plan fast.

“

ose who believe that leaders are supposed to have all the answers, those who believe that leaders do all the thinking and that followers merely do what they’re told, these kinds of leaders in the situations, whether it’s a Panama-like, Haiti-like, or Iraqi-like, become much more authoritative and much more centralized. ey aggregate more and more decisions to themselves.”

So, yet again in my career, I had a navigation problem. This time, you know, we weren’t just in the dark. This time, we didn’t have the wrong map. This time, there was no map at all.

What I’ve presented is three different kinds of navigation problems, one in Panama, in Haiti, and in Iraq. And I would bet that each of you has had similar experiences. I mean, haven’t you, at one point or another, even right now, felt that you have a map but you can’t see the features that should guide your thinking? That you can’t see around you, that you’re in the dark, maybe not physically, but you’re in the dark conceptually, because you can’t figure out where you are? Haven’t you, at some point or another, felt that your map or the map that your organization is using is incomplete or has the wrong terrain features, the wrong prominent terrain features, so that you can’t quite seem to make the right decision at the right time? And haven’t you felt sometimes that you’ve been asked to do things in your organization right now that there’s no map at all to follow? I think, given the pace of change and given the depth and the breadth of change and the complexity of all the environments that we face, regardless of professional sector, any honest answer to those three questions

is, “Yes, yes, and yes.” You can get lost in more ways than being stuck in the swamp in Panama.

So what does a leader do in these kinds of circumstances? That’s really the issue. I’m going to provide at least one answer from my perspective, but, before I do that, I want to be clear about one thing as leaders. The led know when you’re lost. There’s no fooling them. And whether you’re like me, a lieutenant, under a poncho at night, because you have to put a poncho up, get your flashlight out, trying to see where you are, and every private and sergeant around me is saying, “Well, we know what’s going on. The lieutenant is lost.”

The same goes on in every one of your organizations. You cannot fool your followers. So none of us are paid to solve what I’ll call routine problems, problems that recur so often that you have a standard operating procedure to follow them. We’re paid to solve problems that have no answers, or answers that are so temporary that you have to keep adapting as the circumstance is changing. So, with that in mind now, what should leaders do? My answer is that it depends on how

you view yourself as a leader. Those who believe that leaders are supposed to have all the answers, those who believe that leaders do all the thinking and that followers merely do what they’re told, these kinds of leaders in the situations, whether it’s a Panama-like, Haiti-like, or Iraqi-like, become much more authoritative and much more centralized. They aggregate more and more decisions to themselves. Under conditions of ambiguity, like the ones I presented, organizations led by these kinds of leaders generally follow one of four paths. Path number one: the organization could move forward. They accomplish all your objectives, because the leaders have figured it out very quickly and issued orders and the followers execute. We call this in the Army “dumb luck.” This doesn’t happen very often.

More likely, the second path an organization like this takes is that the organization stands still. It’s like me under my poncho, everybody else laying down wondering, “What’s the lieutenant doing under there?” The organization goes nowhere while the leader tries to figure out where he is, where the organization is, and how to move forward. And if this stagnancy goes on long enough, members lose confidence not just in the leadership, but they lose commitment to their organization.

The third path that leaders who are more centralized and authoritative may take is what I’ll call spinning their wheels. There’s lots of movement. Everybody’s busy and everybody’s tired at the end of the day. There’s lots of activity, but there’s no movement forward. The leader is issuing a lot of instructions, but of course, the leader has no idea where the organization is or where it’s going, but he’s doing leadership stuff. He’s telling people what to do, and everybody’s working and busy. But they’re not going anywhere at all. Here, again,

“ Sometimes the best ideas come from those closest to the problem. You don’t look up to find answers; you look down to find answers.”

leadership and the organization become irrelevant. Commitment fades away.

And then the last path is that the organization moves forward in spite of the leaders, where somehow the followers just give lip service to the leaders and take charge. They do what has to be done. But in the process, the organization becomes dysfunctional because there’s this huge gap between what the leader is saying and what the organization is doing. And I could tell a million stories where Army organizations would get orders from their commanders and do what they knew had to be done, and the leader was so incompetent he just followed along as a follower. So this kind of organization does exist. And under conditions of ambiguity, the more complex the navigation problem is, the greater the uncertainty, the more likely an organization led by an authoritative centralized leader goes to options two, three, and four.

There’s another alternative, though. If you’re the kind of leader that says, “Look, I’m the leader, and I am responsible. We are lost. I’ve got to figure this out, but

I can leverage others in figuring it out.”

This is an entirely different answer to the question, “What do leaders do?” And by others, I mean subordinates, peers, and seniors alike. Then the possibilities become something different. When you’re lost like you are in Panama, rather than going under your poncho, you’d send three people out that way, and say “Go 400 meters, 90 degrees that way, tell me what you see. Go that way and tell me what you see. Go that way and tell me what you see. Come back, tell me what you saw, and then let’s find a place on the map that meets all those four locations.” This increases the probability that you’ll find out where you are and increases the probability that you’re going to move forward in the direction that you want to go.

When the map is incomplete, there’s a similar set of activities. The leader starts, first, identifying with others what information he or she needs. Sometimes the best ideas come from those closest to the problem. You don’t look up to find answers; you look down to find answers. In this case, again, the result increases the probability that you’ll identify the right information requirements and increase the probability that you’ll find the right answers to those information requirements, figure out where your organization is, and move forward.

If the leader has no map at all then the leader of the second category taps into the corporate brain of the whole organization, of members, of subordinates, of peers, of seniors, of coalition partners,

of Iraqis, etc. You then find out how to build a map that is good enough, and then use that same set of people to adapt as you move forward, reinforcing things that are going right and identifying very quickly stuff that is not working, and changing it around. So leadership becomes a more corporate kind of affair in those kinds of situations.

In sum, from my view, the leaders of the first category fear admitting that they’re lost. Leaders in the second category already know their followers know they’re lost. Leaders of the first category insulate themselves where leaders of the second category collaborate. Leaders of the first category think that leadership is a zero-sum game. Leaders of the second category know that leadership shared is leadership increased. And when in conditions of uncertainty, leaders of the first category decrease the probability of success; leaders of the second category increase the probability of success.

In today’s kind of fast-paced, changing world, successful leaders collaborate more than their predecessors and they adapt their organizations more often than their predecessors. Organizations without those kinds of leaders are at risk. Darwin’s is not just a theory about biological evolution. It has organizational implications. Organizations die if they can’t adapt. And we all get lost to one degree or another. That’s not the issue. The issue is, “What do you do when you’re lost?”

“ In today’s kind of fast-paced, changing world, successful leaders collaborate more than their predecessors and they adapt their organizations more often than their predecessors.”

What are some of the key challenges you took away from trying to collaborate with a sort of amorphous group? And what are the things you have to do to really make that work?

Jim Dubik

First, you have to recognize that you must collaborate. Don’t get under the poncho. Second, you have to respect that other people may have answers that you have never thought of, and you have to throw rank away. Good ideas don’t have rank. They’re good ideas because they’re good ideas, not because they came from someone. Third, it’s an issue of time management. Because there are so many people with whom to collaborate, the rhythm of meetings that you set up and the way you manage your time will either allow you to collaborate or be an obstacle to collaboration.

Paul Henderson Director of Planning and Communications

US Conference of Catholic Bishops

How do we make sure that we are making right decisions, but also that the people we’re choosing to collaborate with represent a broad spectrum and it doesn’t end up being group-think?

From my experience in the Army, many of our leaders understand collaboration as, “I take my answer to a meeting and convince everyone else it’s right.” That’s not collaboration. Another misunderstanding of collaboration is, “I’m going to get the people who agree with me in a meeting, and then we’re going to talk about my right answer.” Again, that’s not collaboration. If you’re not humble enough to understand that you don’t know the answer and you start from that base, you’re not going to collaborate. You’re going to be in one of these other false modes of collaboration.

So the first is being intellectually honest with yourself and humble enough to say, “Look, I don’t know this.” I can’t tell you how many times in Iraq I’ve said, “Look, you think I know the answer? Why did I call this meeting? You know, we have to figure out the best answer that we can possibly figure out. Then, if it works, fine. If it doesn’t, we’ll adapt it.” You have to respect the fact that others’ experience is equally valid as yours.

If you have a staff with limited imagination, you’re not going to get broad alternative courses of action. And this is where the leader’s responsibility is to seek out the alternatives his or her staff will not give him or her. So you go talk to your

subordinates. While the staff is squirreling away doing staff things, you go talk to your subordinates. You go talk to the subordinates’ subordinates. You go talk to your peers. You might even have a discussion with your seniors about a similar problem. If you don’t have a commander who’s willing to put himself or herself out of the staff mode, then you’re always going to be limited to limited courses of action.

Rev. John Hurley, CSP Executive Director

Department of Evangelization, Archdiocese of Baltimore

Most parish management starts with the fact that many fear we have a vocation crisis, which I think is the wrong place to start. I’m a firm believer that we don’t have a vocation crisis in the Church. I think we have a resistance of being open to the Spirit about where the Spirit’s calling us. In learning from that surge paradigm shift

“

So whether you’re losing a war or losing money or losing priests, crises are opportunities, if you recognize the crisis.”

you discussed, what elements of that can help us in the Church in the United States move to managing for mission rather than managing for vocation crisis?

Well, I’ll leave that to you, Father, about whether it’s a vocation crisis or openness to the Spirit. But from my own professional experience in the surge that you asked about, it took near national disaster for the national leaders to realize, “Hey, it’s not working.” When President Bush in 2006 realized they had bet on the wrong direction and they were losing, it took that level of near disaster for them to be open to an alternative solution. As the Chinese would say, opportunity exists in crisis, but only if you recognize it.

The first step is identifying that you are in a crisis, taking ownership for the crisis, and then making yourself open to alternative ways. That sounds simple, doesn’t it? But look how bad things were in Iraq in 2006 versus today and, comparatively, it’s much better. So that’d be the first thing.

In 1992, after the first Gulf War, the Army had to reduce its size by one-third and its budget by 30 percent. That was a significant emotional event in the life of the Army, and forced us to rethink many, many things about the way we’d done business. Ultimately it ended up in our adopting the whole information sphere and digitization and computers and adding all that stuff to our weaponry as part of ways to increase our combat effectiveness while we decreased size and money.

So whether you’re losing a war or losing money or losing priests, crises are opportunities, if you recognize the crisis.

You also must correctly identify problems in the crisis. Identify the problem, understand the problem, describe the problem from as many different standpoints as you can, and then, lastly, own the problem. Don’t kind of push it away. “Well, we don’t really have a problem, it’s the society,” or, you know, what we did when we changed to the volunteer Army, “We can’t get enough volunteers because American people aren’t patriotic enough.” No, that wasn’t the issue at all. We had a problem. We had to solve it. Identifying a problem, describing it, understanding it, and taking ownership of it are, I would say, equally important as taking opportunities that arise out of crises.

Michael Montelongo Senior Vice President and Chief Administrative Officer Sodexo, Inc.

Structurally speaking, can using a deputy, a COO in the corporate world, perhaps help diocese and parishes with capacity management? As an example, one of the points that was made about the management of the Pentagon was to have a fulltime chief management officer, because there was so much on the Secretary of Defense’s plate to be able to handle the policy issues plus the management and leadership of the department. Maybe something like that can perhaps be appropriate for diocese and parishes?

In the Army, the amount of staff you’re assigned grows as you go up in rank. But in each one of these, there’s a choice that the commander has to make, and it’s the same as what a pastor has to make or the bishop has to make. What’s my role as a leader? And what’s my role as a manager? They’re related. They’re both inherent to me. They can’t be separated. But what do I do? When I divest day-to-day management to my executive officer or my deputy commander or my COO, I don’t divest it like an arrow. I don’t just shoot it, fire and forget, and it’s gone. You can’t. You have to establish with your executive officer, deputy, COO, so that you meet with that person and his or her key subordinates at a certain period so that the staff feels that they have sufficient claim on your time. This has to be with the right frequency that they can then use their initiative within their intent between those periods. They shouldn’t bother you during these periods. This liberates you to do the leadership stuff, the counseling stuff,

the performance, the observation, the visiting, the battlefield, on the leadership side. So there is a structural part to leadership, just like there’s a time management aspect of leadership. The size and complexity of the structure should be mirrored by the scope of the job. You would expect the global religious community would have a different structure than a local parish.

Are there any strategies, in regards to trying to come up with a common mission and being able to place that mission first?

All of us face that challenge of prioritization. As a leader, if you’re unwilling to make priority decisions, then your organization’s going to look more like a diffracted light than a focused light. You’re not going

“

to have laser focus if you don’t set priorities, and that was part of a question I had here before about making a paradigm shift in Baghdad. We had to get a laser focus on three important issues. It’s inherent in the leadership responsibility to set the direction of the organization, set the priorities, set the vision, motivate people, and then have a management structure to keep the organization on that track. That’s why I separate leadership from management, but I can’t separate the execution. Leaders set direction, set vision, motivate and inspire followers, and then set up a management structure that keeps the organization on track. Otherwise, the organization will go the way it wants to go, because all human beings know that they don’t need leaders, that they know more than anybody else.

Leaders set direction, set vision, motivate and inspire followers, and then set up a management structure that keeps the organization on track.”

2012 Annual Meeting | Georgetown University | June 27-28, 2012 www.TheLeadershipRoundtable.org/2012AnnualMeeting

Opening Prayer

Fr. Jack Wall

President, Catholic Extension

Trustee, National Leadership Roundtable on Church Management

Come, Spirit of God. Fill the hearts of your faithful, and kindle in us this night the fire of your love. Hover over this festive night and invade our hearts. Infuse us with the gift of wisdom in our deliberations, and

the gift of joy, joy in our celebration, for tonight we honor and pay deep tribute to two wondrous expressions of your life-giving spirit among us. The good and compassionate works of Catholic Charities USA, and the radiant lives of our women religious whose story is so beautifully told in the exhibit, Women & Spirit: Catholic Sisters in America. Spirit of God, we implore you to abundantly bless these two powerful experiences of your transforming love as they passionately and steadfastly give witness to the power, the beauty and the hope of risen life among your people, throughout our country, and especially in the lives of the poor. And Spirit of God, through their witness, we pray that you would strengthen our hearts and heal our wounds and unleash our creativity and renew our commitment to do your work of becoming your blessing into the world. We ask that you bless this food we share that it might become the bond that brings us together. This is our prayer, through Christ our Lord, Amen.

Michael O’Loughlin Communications Manager, National Leadership Roundtable on Church Management

When the Leadership Roundtable was founded, its leaders were determined to understand the precise nature and com -

“

e Leadership Roundtable is uniquely situated to solve the temporal challenges facing the Church because we focus solely on solutions and we are able to bring together individuals with varied view points and different ideas to address common challenges.”

plexities of contemporary challenges facing the Church, and to approach these challenges in a positive and hopeful way. In addition to bringing the expertise of the laity from an array of sectors, the Leadership Roundtable seeks out examples of best practices already at work in the Church, practices that promote sound stewardship, transparency, accountability, excellence, and innovation. We then advocate for the widespread adoption of these practices throughout the Church.

A few years ago, at a previous annual meeting, the Catholic journalist and author John Allen said that the Leadership Roundtable is uniquely situated to solve the temporal challenges facing the Church because we focus solely on solutions and we are able to bring together individuals with varied view points and different ideas to address common challenges. Over the years, we’ve been honored to recognize a slate of extraordinary, effective, hopeful, and dynamic individuals, institutions, and organizations, holding up their ministries as examples deserving of praise and emulation. We’re honored to include Catholic Charities USA and Women & Spirit in that group tonight.

Kerry Robinson

Executive Director, National Leadership Roundtable on Church Management

It is such a privilege to honor Catholic Charities USA. Ostensibly, we honor and award this best practice plaque to

Catholic Charities USA because of their commitment to collaboration with federal, state, and local governments, with other faith-based and secular non-profits, and because Catholic Charities USA routinely is given the highest marks in terms of management of finances and people.

These are all the values that the Leadership Roundtable exists to promote and serve. But permit me, on a personal level, to speak on behalf of my fellow trustees and staff at the Leadership Roundtable. Were it not for Catholic Charities and the love that is provided in a concrete way every single day across this country through their work and ministry, our Church would be radically impoverished. For all that Catholic Charities does, and the fact that Catholic Charities is an integral part in the largest global humanitarian organization in

the world, we are deeply, deeply grateful. The 2012 Leadership Roundtable Best Practices Award is presented to Catholic Charities USA, honoring its distinguished service to and the advocacy on behalf of the poor and for innovative collaborations and exemplary stewardship of resources.

President Catholic Charities USA

Well, first of all, I’m not quite sure how I can adequately say thank you for this great award. I think half of the honor of receiving an award comes from the recognition of the work that you do and the other half of the honor comes from the organization who gives the award. And I have to say that, since its beginning, I have admired and

supported the work of the National Leadership Roundtable. I’m especially pleased with the theme that you have chosen this year, “Managing for Mission: Building Strategic Collaborations to Strengthen the Church.” Catholic Charities could not do what it does without working in a collaborative fashion. The definition is always a good place to start. To collaborate: to work jointly with others or together, especially in an intellectual endeavor. To cooperate with or willingly assist an enemy of one’s country, and especially an occupying force. To cooperate with an agency or instrumentality with which one is not immediately connected.

“ As we look at Catholic social teaching, and the principles that we find, such as dignity and respect for all human beings and a commitment to make the common good a priority, our relationships and responsibilities must be established. We can see in them a mandate to collaborate. ”

You can see why people have a lot of misgivings about collaboration. It’s inherent in the definition that there is tension and there are turf issues, but should that stop us? I don’t think so.

What does nature have to tell us about collaboration? We can look at certain examples, like bees and ants, and we can see for them it is not a matter of thriving, it is a matter of surviving. Now you can contrast that with human beings and how we have an attitude of rugged individualism. Personally, I think rugged individualism is a myth. We are social beings to our very core.

What does our faith and religious values have to tell us about collaboration? As we look at Catholic social teaching, and the principles that we find, such as dignity and respect for all human beings and a commitment to make the common good a priority, our relationships and responsibilities must be established. We can see in them a mandate to collaborate. In Deus Caritas Est we see the threefold responsibility of the Church: evangelization, common sacramental life, and charity to a world in need. All of these require working together. So, we can see that collaboration is a good idea on a practical level. But when we get to the level of faith, then collaboration becomes a mandate.

How have we done with collaboration as American Catholics? We can go back to the beginning of social ministry in the United States, in 1727, when the Ursuline sisters left Paris and came to the city of New Orleans in New France. Remember, that was 50 years before the Declaration of Independence.

How have we done with collaboration as a country? In 1866, the bishops of this country all got together and made this statement: “It is a very melancholy fact, and a very humiliating avowal for us to make, that a very large portion of the vicious and idle youth of our principal cities are the children of Catholic parents.”

Can we write this off as just a group of grumpy old men? Well, before we do let’s take a look at the reality of New York in 1862. Seventy percent of the inmates of public almshouses, 50 percent of the city’s criminals, and 50 percent of those in reformatories all were born in Ireland. At the time, that means they were all Catholic as well. The New York City leaders who were not Catholic referred to them as “so much accumulated refuse.” So what’s the big deal? It reminds us of two things. First, one thing we forget is that for the majority of our history we were and have been an immigrant Church. Even into the early 1900’s, over half of the Catholics in this country were not born here. As an immigrant Church, we were not only a Church who served the poor, we were the poor.

Second, did the immigrants receive a welcome as Catholics in this country? This is another thing that we sometimes forget. There was a deeply rooted prejudice against Catholics in this country. Those of you who have been to the Statue of Liberty in New York City may have read Emma Lazarus’ poem that’s on the base of the statue. The poem says, “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, the wretched refuse of your teeming shore, send these, the homeless, tempesttossed to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!” Those words weren’t exactly the experience that most immigrants had, especially Catholic immigrants.

When you recall the words of the bishops in 1866, I think they were a call to action for Catholics. “We are connected to this issue. We need to solve this.” So what did we do? We built systems to respond to this and we got to the point where you could ask what is the largest private education system in the United States; it’s the Catholic education system. The largest healthcare system? The Catholic

“ We have to ask ourselves, “Are we asking the right questions? Are we making the right invitations to this generation? ”

healthcare system. Social service system? Catholic Charities and the other great works done by religious orders.

All of that is to say that we responded to that call to action, and we succeeded, and we continue to succeed today. That is collaboration. It was collaboration out of necessity. The challenges that we face today are different challenges, even though, once again, we cannot put aside the issues that immigrants face in this country. But the point is we’ve done it before, we can do it again. However, as we look at all the great Catholic institutions, we can’t forget that the primary locus, or place, of social ministry is the parish. We as institutions can only do what we do because there is a network, a foundation, of parishes that carry out the day-in-andday-out ministry to neighborhoods and communities. We presuppose that, and I think in most communities, the parish is Catholic collaboration at its best.

Catholic Charities is also called to collaborate in the public square. I’m not going to go into this in any depth, but just to say that our involvement in the public square is ambiguous, controversial, threatening, and it is absolutely necessary. So I give you three resources that help me to try to stay on a clear course. A book by John Dilulio called The Godly Republic: a Centrist Blueprint for America’s Faith-Based Future, in which he tries to capture the mind of the

framers of the Constitution and show that not only did they think there was a place for religious organizations in our society, constitutionally, but they thought it was essential, because they said we are setting out to establish a Godly republic.

The second book, by Professor Stephen Monsma, Pluralism and Freedom: FaithBased Organizations in a Democratic Society, basically gives the historical development of how religious organizations have contributed, and how greatly they have contributed, to our society. And the third book, by Cardinal Donald Wuerl, Seek First the Kingdom: Challenging the Culture by Delivering Our Faith, which comes from the spiritual dimension of engaging society. All of these books show that we can agree on the goals. Sometimes we may have different strategies, but we, without a doubt, have a place in the public square.

Some people question exactly how we should engage the public square. There are some voices out there that say we should circle the wagons because we are under attack, that we should withdraw and pull ourselves away from society. Should we, as Catholics, circle the wagons? The last time we did that was about 400 years ago at the Council of Trent and unfortunately it lasted for about 350 years. But the question we have to ask ourselves is, “What is our tradition in the greater scheme of things?” And I think our tradition has been and should be one of engagement.