7 minute read

Cover Story

What is The Endangered Species Act and What Does it Mean for Turfgrass Managers What is The Endangered Species Act

By Estefania G. Polli and Travis Gannon

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has encountered difficulties complying with the ESA (Endangered Species Act), resulting in the completion of less than 5% of its obligations under the Act. As a consequence, EPA faces over 20 lawsuits and impeding deadlines for over 50 pesticides by 2030. Moreover, failure to fulfill its obligations has led to the suspension of pesticide registrations for three dicamba products in agronomic crop systems on February 6, 2024. These regulatory challenges and legal risks have created confusion and uncertainty for the pesticide industry and end-users.

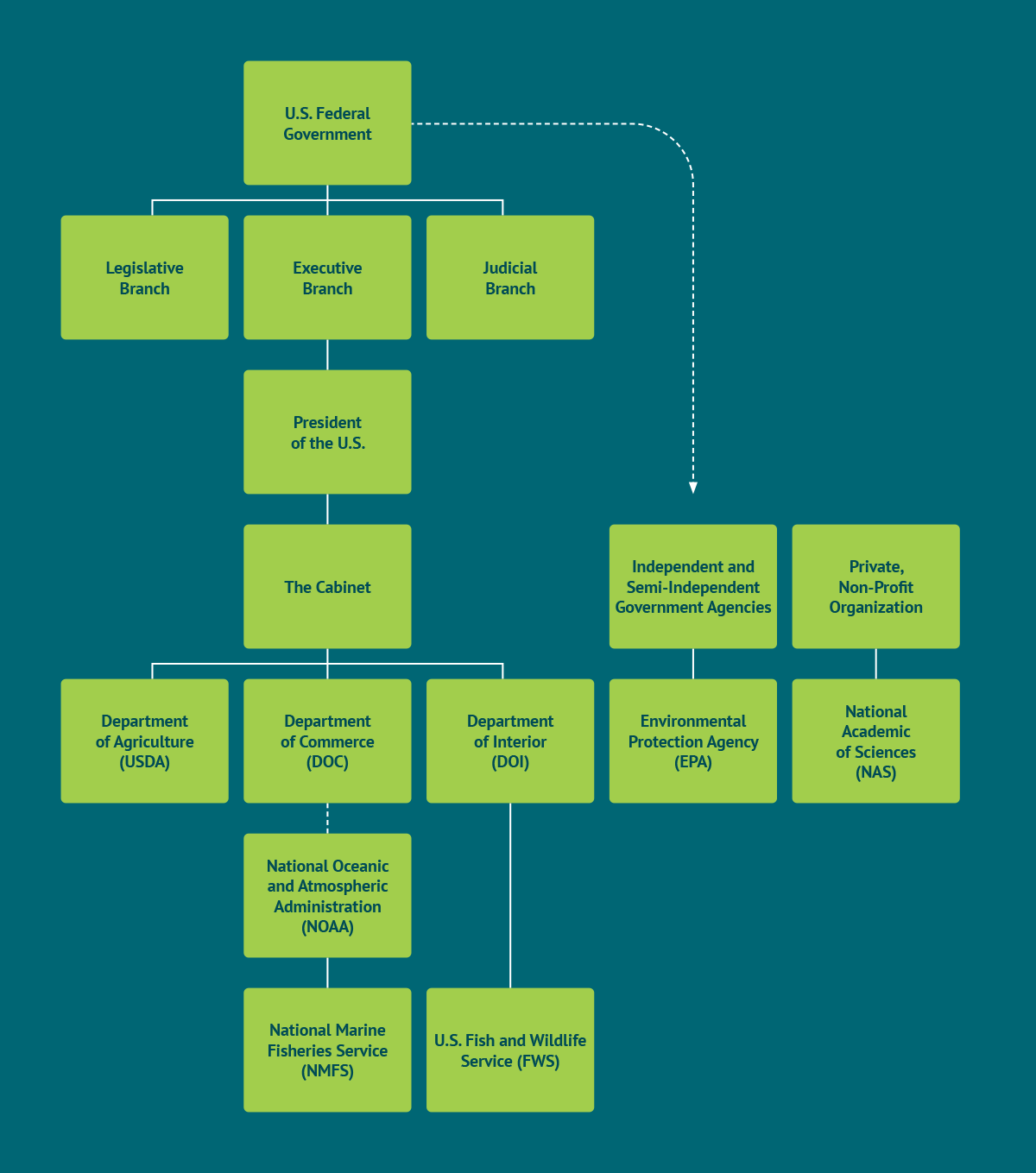

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 was designed to protect endangered and threatened species, along with their habitats. Administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), the ESA seeks to prevent species extinction and promote habitat conservation. Federal agencies, including the EPA, must consult FWS and NMFS to ensure their actions do not harm endangered or threatened species or their habitats.

EPA’s responsibilities under the ESA include regulating pesticides establishing the Endangered Species Protection Program in 1988. However, the process of evaluating the impact of pesticides on species and their habitats has been slow, expensive, and difficult. In response, collaborative efforts between the EPA, FWS, NMFS and U.S. Department of Agriculture have been made to develop more efficient ecological risk assessment methods. Moreover, in 2021, the EPA initiated the development of workplans to continue improving its compliance with the ESA.

The latest workplan highlights measures taken and planned to improve protection on non-target species. These measures include pilot species identification, impact of new pesticides on listed species, development of region-specific strategies using the Bulletins Live! Two (BLT) website, exploration of mitigation strategies for nonagricultural uses, and implementation of early ecological mitigation for groups of pesticides through the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) Interim Ecological Mitigation developed by the EPA. This Interim step proposes additional mitigation and conservation measures, aiming to reduce negative effects or potential risks of pesticide use, particularly caused by water runoff, soil erosion, and spray drift.

Currently, its scope encompasses only agronomic crops, though there is an anticipation of integrating turfgrass systems into it in the near future. While EPA has drafted some general guidelines for major agronomic crop production systems, there is limited information available specific to managed turfgrass sites and other specialty crop systems. EPA has stated they plan to explore strategies for pesticide use in non-agricultural areas, specifically mentioning collaboration with FWS and the American Mosquito Control Association to develop mitigation measures for certain insecticides. However, they did not specify what those mitigations might be. Similarly, EPA is exploring broad mitigation measures to minimize exposure when pesticides are used in residential settings (and presumably other settings), though no specific mitigations were mentioned. Additionally, EPA plans to collaborate with various pesticide user groups to better devise these mitigation strategies indicating there may be an opportunity for you (as a professional pesticide applicator) to provide feedback.

The proposed changes are outlined below:

Water Runoff and Soil Erosion

Additional measures would primarily apply to pesticides with an organic carbon partitioning coefficient (Koc) of 1,000 L kg-1 or less, indicating moderate to high mobility in soil. Moreover, these measures include two surface proposed water protection statements that applicators would follow when precipitation occurs or is forecasted: “do not apply during rain” and “do not apply when a storm event likely to produce runoff from the treated area is forecasted to occur within 48 hours following application.” Meanwhile, growers would be responsible for selecting mitigation measures from a predefined pick list. The EPA may propose one or more measures from the pick list based on specific ecological risks, benefits, and pesticide use. Examples of reduction measures on the pick list include vegetative filter strips, cover crops, field borders, and riparian buffer strips or zones, none or reduced tillage, contour buffer strips, and vegetative barriers.

Spray Drift

Application restrictions regarding droplet size, windspeed, and release height limits, as well as the aerial application prohibitions, will remain on the label. In addition to these restrictions, the EPA intends to propose spray drift buffers from aquatic habitats (e.g., lakes, reservoirs, rivers, permanent streams, wetlands or natural ponds, estuaries, and commercial fish farm ponds) and conservation areas (e.g., public lands and parks, Wilderness Areas, National Wildlife Refuges, reserves, conservation easements).

How does ESA affect the pesticide industry and applicators, sod growers, and turf managers?

Pesticide Industry

The FIFRA Interim Ecological Mitigation serves as the initial framework to registrants to address pesticide risks to nontarget species during both registration and registration review processes. For each FIFRA action, the EPA will consider a menu and propose, based on the risks and benefits of the particular pesticide, which specific measures to include on the pesticide label. Moreover, the EPA has proposed incorporating language for pesticide products, pesticide incident reporting, insect pollinators protection, and geographical restrictions by directing users to reference BLT website.

Pesticide Applicators

Pesticide labels are evolving to include more detailed directions and restrictions. Applicators are responsible for carefully reading and following these instructions. Additionally, as per label instructions, they will likely be required to consult the BLT online database and comply with any mitigation specified in a Bulletin for the application area. It is important to note that Bulletins do not replace or override any additional restrictions that a state may impose. Thus, applicators need to be aware of pesticide regulations at both state and federal levels. As previously stated, implications for turfgrass managers remain ambiguous at this time; however, an example of specific geographical use limitations in North Carolina currently for four dicamba formulations approved for use on dicamba-tolerant cotton and soybean crops is included in Figure 2.

Turfgrass Managers

The implementation of additional mitigation and conservation measures may increase labor and expense for turfgrass managers. Some of these measures may require significant changes to existing systems, which could involve investments in infrastructure, equipment and workforce. However, there are potential long-term benefits, including improved soil health, enhanced biodiversity, and reduced environmental impact. Further, land managers may qualify for financial assistance or incentive programs from public and private organizations to help offset implementation costs and encourage the adoption of these measures.

Overall, the ESA will impact land managers by requiring them to be knowledgeable about the endangered species present in areas where they apply pesticides and to implement appropriate conservation efforts to ensure those species aren’t adversely affected. As previously stated, what compliance looks like in specialty cropping systems, including managed turfgrass areas is unclear at this time.

References

[US EPA] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2022) ESA WORKPLAN UPDATE: Nontarget Species for Registration and Other FIFRA Actions. https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2022-11/esa-workplan-update.pdf. Accessed: May 14, 2024.

[US EPA] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2023) Conventional Pesticide Registration. https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/conventional-pesticide-registration. Accessed: January 30, 2024.

[US EPA] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2023) Endangered Species: Information For Pesticide Users. https://www.epa.gov/endangered-species/endangered-species-information-pesticide-users. Accessed: January 31, 2024.

[US EPA] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2023) EPA Advances Early Pesticides Protections for Endangered Species, Increases Regulatory Certainty for Agriculture. https://www.epa.gov/pesticides/epa-advances-early-pesticidesprotections-endangered-species-increases-regulatory. Accessed: February 5, 2024.

[US EPA] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2023) Tips for Reducing Pesticide Impacts to Threatened and Endangered Species. https://www.epa.gov/endangered-species/tips-reducing-pesticideimpacts-threatened-and-endangered-species. Accessed: February 5, 2024.

[US EPA] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2024) Protecting Endangered Species from Pesticide. https://www.epa.gov/endangered-species. Accessed: January 30, 2024.

[US EPA] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2024) Bulletins Live! Two — View the Bulletins. https://www.epa.gov/endangered-species/bulletins-live-two-view-bulletins. Accessed: May 25, 2024.