Survey of Turfgrass Irrigation Water Quality in Pennsylvania

Winter 2023 • Vol. 12/No. 1

KAFMO Marks 25 Years of Little League Baseball ® World Series Partnership

TAK E YOUR TURF TO THE NE XT LEVEL W I TH.. . Cont ac t Fish er & S on Compa ny toda y to provid e you wi th the too ls an d exp erti s e for all ReG ene rate p roduct s to exce ed y our t urf and horticultu re exp ectati ons. A proprietary soil surfactant designed to Reduce LDS Enhance Irrigation Efficiency Reduce Plant Stress Thom Mahute - 717-940-0730 Bob Seltzer - 610-704-4756 Dave Hunley - 215-262-3912 Zach Owen - 609-454-7727 ✓ ✓ ✓

V. Halyard – Storylounge Photo

V. Halyard – Storylounge Photo

4 Pennsylvania Turfgrass • Winter 2023 16 8 Vol. 12 / No. 1 • Winter 2023 5 Advertiser Index 6 President’s Update 6 Penn State Turf Team 18 Penn State News Departments 8 Survey of Turfgrass Irrigation Water Quality in PA 14 Playing the Long Game: Overcoming Supply Chain Challenges in Turfgrass Management 16 KAFMO Marks 25 Years of Little League Baseball ® World Series Partnership Cover Story Feature Between the Lines Pennsylvania Turfgrass Council P.O. Box 99 Boalsburg, PA 16827-0550 Phone: (814) 237-0767 Fax: (814) 414-3303 info@paturf.org www.paturf.org Publisher: Leading Edge Communications, LLC 206 Bridge Street, Suite 200 Franklin, TN 37064 Phone: (615) 790-3718 Fax: (615) 794-4524 info@leadingedgecommunications.com Pennsylvania Turfgrass Editor Max Schlossberg, Ph.D. Penn State University • mjs38@psu.edu Pennsylvania Turfgrass Associate Editor President Tom Fisher Wildwood Golf Club – Allison Park, PA (412) 518-8384 Vice President Rick Catalogna Harrell’s Inc Territory Manager (412) 897-0480 Secretary-Treasurer Shawn Kister Longwood Gardens, Inc. –Kennett Square, PA (484) 883-9275 Past President Pete Ramsey Range End Golf Club – Dillsburg, PA (717) 577-5401 Director of Operations Tom Bettle Penn State University Assistant Director of Operations Nicole Kline Pennsylvania Turfgrass Association Directors Steve Craig Centre Hills Country Club Tanner Delvalle Penn State Extension Elliott Dowling USGA Andy Moran University of Pittsburgh Tim Wilk Scotch Valley Country Club Matt Wolf Penn State University Find this issue, Podcasts, Events and More: THETURFZONE.COM

5 Winter 2023 • Pennsylvania Turfgrass Advertiser Index Aer-Core, Inc. Inside Back Cover www.aer-core.com Aqua Aid Solutions 7 www.aquaaid.com Coombs Sod Farms 13 www.coombsfarms.com Covermaster, Inc. 13 www.covermaster.com DryJect ...................................................... 9 East Coast Sod & Seed 18 www.eastcoastsod.com Ernst Conservation Seeds 11 www.ernstseed.com Fisher & Son Company, Inc. Inside Front Cover www.fisherandson.com FM Brown’s & Sons 11 www.fmbrown.com Forse Design Incorporated ...................... 3 www.forsegolfdesign.com Greene County Fertilizer Co. 5 www.greenecountyfert.com Mitchell Products Inside Back Cover www.mitchellsand.com Progressive Turf Equipment Inc. ........... 17 www.progressiveturfequip.com Seedway 5 www.seedway.com Shreiner Tree Care 11 www.shreinertreecare.com STEC Equipment Back Cover www.stecequipment.com Fertility Forward® Fertilizer MFR/HQ: Greensboro, GA ▪ Chemical Distributor of L&O pest control products DIRECT SHIP GreeneCountyFert.com MAXIMIZE YOUR FERTILIZER EFFICIENCY Greene County Fertilizer Company is well-known for biostimulants. Our unmatched cost-to-performance values extend beyond these products with N-Charge™ 28% sustained release nitrogen and GreeneCharge™ 26% with minors. These powerful nitrogen formulas standing alone or blended with our biostimulants will charge up your fertility program. POWER UP YOUR SOIL High Performance Plant Nutrients Fertilizers ▪ Specialty Products Soil Amendments ▪ Custom Blends Our bio-based fertilizers & specialty fertility products are blended to feed plants, improve soil fertility and build topsoil.

Throughout the course of a career, you have likely found yourself in a sweet spot with the crew you managed or were a part of. Everybody covered for each other, tasks were appreciatively assigned and graciously completed. It wasn’t work; it was fun. Inevitably the pieces of that puzzle seek out greater opportunities in greener pastures, or they (gasp) leave the industry altogether. At that junction, the emotional attachment to that employee can cloud the judgement required to successfully navigate the approaching storm… or opportunity for growth.

An empathetic manager will recognize the void left in the wake of a key departure. What have you become comfortable with (read: take for granted) in your fishbowl? What fading social dynamic will need to be supplemented through improved personal interaction (not just talking shop) with your staff? What will you or the staff NOT miss about the departure?

A shrewd manager will see this as a clear and concise recalibration of your maintenance operation. To be blunt, how can the output of that full time equivalent be replaced? What simple idiosyncratic tendencies will now slip through the cracks? What will now fall on the shoulders of the remaining crew? Do I have what I need in payroll?

A successful manager will produce a composite of these considerations and come to the realization that not any one person is replaceable. Successful coaches rarely lament injuries or departures following a loss no matter the magnitude. We wouldn’t accept that as fans; should we expect that from our customers? Next (wo)man up is a tired but valuable platitude. Filling an empty seat requires a balance of discriminatory preference and com promise. It is incumbent upon that replacement to showcase their strengths while also expressing a level of humility when shown in the light. Your setting of expectations through thoughtful explanation requires communication skills not always tactfully dispatched. Like any good habit, maximizing the potential of those under your tutelage is infectious and will often raise all ships in your proverbial harbor.

As an agent responsible to your Board or Owners, the hard reality of a budget is everpresent. As an advocate responsible for your employees, their needs are omnipresent. Not to suggest showing your cards is ever the right thing, but open and honest discussion with all stakeholders will bridge gaps, manage expectations, and hopefully end up in your favor. Do the hard work as a manager, so that those you manage can do the hard work on the ground, making the rest easy.

PTC

The

the association, its staff, or its board of directors, Pennsylvania Turfgrass, or its editors. Likewise, the appearance of advertisers, or PTC members, does not constitute an endorsement of the products or services featured in this, past or subsequent issues of this publication. Copyright © 2022 by the Pennsylvania Turfgrass Council. Pennsylvania Turfgrass is published quarterly. Subscriptions are complimentary to PTC members. Presorted standard postage is paid at Jefferson City, MO. Printed in the U.S.A. Reprints and Submissions: Pennsylvania Turfgrass allows reprinting of material published here. Permission requests should be directed to the PTC. We are not responsible for unsolicited freelance manuscripts and photographs. Contact the managing editor for contribution information. Advertising: For display and classified advertising rates and insertions, please contact Leading Edge Communications, LLC, 206 Bridge Street, Suite 200, Franklin, TN 37064, (615) 790-3718, Fax (615) 794-4524.

Jeffrey A. Borger

Senior Instructor in Turfgrass Weed Management 814-865-3005

• jborger@psu.edu

Michael A. Fidanza, Ph.D.

Professor of Plant & Soil Science 610-396-6330 • maf100@psu.edu

David R. Huff, Ph.D.

Professor of Turfgrass Genetics 814-863-9805

Brad Jakubowski

• drh15@psu.edu

Instructor of Plant Science 814-865-7118 • brj8@psu.edu

John E. Kaminski, Ph.D. Professor of Turfgrass Science 814-865-3007 • jek156@psu.edu

Peter J. Landschoot, Ph.D. Professor of Turfgrass Science 814-863-1017 • pjl1@psu.edu

Ben McGraw, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Turfgrass Entomology 814-865-1138 • bam53@psu.edu

Andrew S. McNitt, Ph.D. Professor of Soil Science 814-863-1368 • asm4@psu.edu

Max Schlossberg, Ph.D.

Associate Professor of Turfgrass Nutrition / Soil Fertility 814-863-1015 • mjs38@psu.edu

Al J. Turgeon, Ph.D.

Professor Emeritus of Turfgrass Management aturgeon@psu.edu

Wakar Uddin, Ph.D.

Professor of Plant Pathology 814-863-4498

• wxu2@psu.edu

6 Pennsylvania Turfgrass • Winter 2023 President’s Update Penn State Turf Team

Tom Fisher

President

NOBODY

Pennsylvania Turfgrass Council (PTC) serves its members in the industry through education, promotion and representation. The statements and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily represent the views of

IS REPLACEABLE

SamStimmel,AQUAAIDSolutions Email:sstimmel@aquaaid.com Phone:724.825.1906 BillBrown,CGCS,AQUAAIDSolutions Email:bbrown@aquaaid.com Phone:484.889.1548

I Survey of Turfgrass Irrigation Water Quality in Pennsylvania

rrigation is a vital management practice for golf courses, sports turf facilities, and lawns throughout the United States. A survey conducted in 2013 by the Golf Course Superinten dents Association of America revealed that golf courses in the northeast United States, including Pennsylvania, used approxi mately 30.7 billion gallons of water (4). Although water use by golf courses in the northeast is generally much less than in the southern United States, population growth and competition for water from businesses and industry has resulted in increased costs and scrutiny of turfgrass irrigation practices by regulatory agencies. In the future, turfgrass managers in Pennsylvania may be forced to use more recycled or marginal quality water, which will likely involve frequent testing of irrigation water and reliance on advice from pri vate consultants, university specialists, and test laboratory personnel.

By Peter Landschoot, John Spargo, and Benjamin McGraw

This article is a condensed summary of results from a survey of turfgrass irrigation water in Pennsylvania. The complete survey is published in Crops, Forages, and Turfgrass Management and can be accessed at: https://acsess. onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/cft2.20157?af=R

In 2007, Penn State’s Agricultural Analytical Services Labora tory (PSAASL) began a testing program for drinking and irriga tion water as a service to individuals in Pennsylvania and the nearby states. Although studies of drinking water quality in Penn sylvania have been published (7,8), data summaries of turfgrass irrigation water quality are generally not available to the public.

The main objective of this survey was to create a baseline profile of turfgrass irrigation water quality in Pennsylvania that can be used for comparison with data from other regions or future water quality surveys within Pennsylvania. A secondary objective was to establish “normal range” guidelines for test reports corresponding to values falling within 90th and 10th percentiles for 24 irrigation water quality parameters. Normal ranges can serve as references for practitioners and consultants when comparing irrigation water quality used at one facility with the range of values generated from water samples col lected throughout Pennsylvania.

Collection and Analysis of Irrigation Water Samples

Volunteers, including research technicians, extension educators, turf product distributors, and irrigation specialists collected water samples from turfgrass irrigation water sources in Pennsyl vania. Samples were taken directly from irrigation system valves (“quick couplers”) after 30 to 60 seconds of flushing, or from ponds, rivers, and streams as close to intake ports as possible. Sources composed of effluent or recycled wastewater, or water amended with acid, fertilizer, or any other substance were ex cluded from this survey.

Samples were collected from golf courses (174), sports turf facilities (12), sod farms (2), a turfgrass research facility (1), and a large display garden (1) from 2007 to 2019. Only one sample was collected from each facility unless multiple irrigation water sources were used, in which case one sample was collected from each source. Samples were collected from 50 of the 67 counties in Pennsylvania, with most taken from counties with numerous golf courses. All 190 samples collected for this survey were analyzed for pH, alkalinity, hardness, electrical conductivity (EC), total dissolved solids (TDS), sodium, sodium adsorption ratio (SAR), bicarbonate, carbonate, calcium, magnesium, residual sodium carbonate (RSC), chloride, and boron. Of the 190 samples, 180 were also analyzed for nitrate-N, ammonium-N, phosphorus, po tassium, sulfur, iron, manganese, copper, molybdenum, and zinc.

8 Pennsylvania Turfgrass • Winter 2023

Cover Story

The surface is very “puttable.” The dots are sand that is level with the turf.

DryJect® is a high-pressure, water based injection system that blasts holes through the root zone and fractures the soil profile. Plus, it automatically fills holes as it aerates. DryJect® makes a big difference

and Play Right Away! Decreased down time, increased revenue.

Aerate

in playability … right away! DRYJECT.com Dryject Eastern PA Mike Zellner (484)-357-9197 mike@dryject.us Dryject Western PA Ben Little (412)-610-9001 ben.j.little@comcast.net Call Today! NO BUMPS! One hour following a DryJect® treatment. Aerate, amend and play right away

Water quality parameter median values were used as the descriptive measure of central tendency and data were further segmented into quartiles, as well as the 95th, 90th, and 10th percentiles (Table 1). Irrigation water quality data collected in this survey are intended to provide a broad profile of water quality over a range of sources, in different years and months of the growing season, and across regions with varying geology and topography.

Summary of Irrigation Water Survey Results

pH and alkalinity

Irrigation water can be classified as acid, neutral, or alkaline. Any pH value below 7.0 is considered acid, a value of 7.0 is neutral, and a pH above 7 is alkaline. Survey results show that irrigation water pH ranged from 6.4 to 10.3, with a median of 7.7 (Table 1). 90% of the samples were equal to or below 8.3, and only 10% were equal to or below 7.1.

Alkalinity represents the neutralizing capacity of water and if present in adequate amounts, buffers freshwater in the approxi mate pH range of 6.0 to 8.5 (5,9,11). When alkalinity falls below 20 mg/L of CaCO3, water can undergo wide daily and seasonal pH fluctuations, causing stress, poor development, and sometimes the death of aquatic animals (9,11).

Irrigation water survey data show an alkalinity range from 4 to 340 mg/L of CaCO3 with a median value of 77 mg/L (Table 1). Results indicate 90% of the samples were equal to or below 167 mg/L CaCO3 and 10% were equal to or below 29 mg/L CaCO3. Only two irrigation water samples in this survey had total alkalinity values below 20 mg/L CaCO3, and both samples were from ponds on golf courses. This survey-based normal range falls within the published normal range of 20 to 300 mg/L of CaCO3 for turfgrass irrigation water given by Carrow and Duncan (2).

Electrical conductivity (EC) and total dissolved solids (TDS)

Two water quality indicators used to express soluble salts in turf grass irrigation test reports are EC and TDS. EC is a measure of the degree in which water conducts electricity. It is determined by passing an electrical current through a water sample and record ing the resistance in mmhos/cm or dS/m. EC is used to estimate TDS in ppm or mg/L in water using the equation: TDS (mg/L) = EC (dS/m) x 640. EC and TDS provide an indication of dissolved salts but do not indicate which salts are present in the water. Ac ceptable TDS values for turfgrass irrigation water range from 200 to 500 mg/L (EC ~ 0.31 to 0.78 dS/m) (2). TDS values higher than 2,000 mg/L (EC ~ 3.1 dS/m) can damage turfgrasses (2).

Total Alkalinity (mg/L) 340 4 204 167 128 76 48 29 Hardness (mg/L) 760 13 377 275 193 127 70 39 ECa (dS/m) 1.38 0.05 0.93 0.73 0.50 0.34 0.21 0.11 TDSb (mg/L) 883 31 595 468 318 217 131 73 Na (mg/L) 97 <0.5 68 47 30 15 8 3 SARc 2.76 0.04 1.95 1.70 1.11 0.61 0.33 0.12

Bicarbonates (mg/L) 414 0 249 202 153 87 55 29 Carbonates (mg/L) 39 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 Ca (mg/L) 213 3 104 76 53 35 19 11 Mg (mg/L) 70 1 32 23 14 9 5 2 RSCd (meq/L) 0.9 -10.6 0.1 -0.1 -0.4 -0.8 -1.5 -2.4 Cl (mg/L) 221 <1 138 97 63 26 11 4 B (mg/L) 0.42 <0.01 0.13 0.09 0.05 0.02 <0.01 <0.01

aEC = Electrical conductivity of irrigation water

bTDS = Total dissolved solids of irrigation water, estimated by multiplying EC values by 640

cSAR = Sodium adsorption ratio of irrigation water

dRSC = Residual sodium carbonate

10 Pennsylvania Turfgrass • Winter 2023

Cover Story • continued

TABLE 1. Maximum and minimum values, and 95th, 90th, 75th, 50th (median), 25th, and 10th percentiles for 14 irrigation water quality parameters based on analyses of 190 turfgrass irrigation water samples collected between 2007 and 2019. Water quality component Maximum value Minimum value 95th percentile 90th percentile 75th percentile Median value 25th percentile 10th percentile pH 10.3 6.4 8.4 8.3 8.0 7.7 7.4 7.1

If using irrigation water with a TDS concentration higher than 500 mg/L, attention should focus on irrigation duration and frequency, drainage, and turfgrass species selection.

TDS values in this survey ranged from 31 to 883 mg/L, with a median value of 218 mg/L (Table 1). Only 10% of the samples had a TDS value at or below 70 mg/L, whereas 90% of the samples had a TDS at or below 480 mg/L. Seventeen of the 190 sam ples analyzed in this survey exceeded 500 mg TDS/L, which is sometimes considered a threshold for stress in salt-sensitive plants such as annual bluegrass and Kentucky bluegrass in arid climates. Whereas the 500 mg TDS/L threshold for salt-sensitive turfgrasses may be a concern in arid regions where irrigation amounts are high, it may be less of a concern in Pennsylvania, where natural pre cipitation is close to 40 inches per year and irrigation amounts tend to be lower.

Sodium and sodium adsorption ratio (SAR)

Sodium concentrations in irrigation water survey samples ranged from 0.5 to 97 mg/L with a median of 15 mg/L (Table 1). Of the 190 samples included in this survey, 95% had sodium con centrations at or below 70 mg/L, the upper limit listed in PSAASL water analysis reports. The survey results showed that 90% of the samples had sodium concentrations equal to or below 47 mg/L and 10% were equal to or below 3 mg/L.

SAR provides a useful indicator of the potential damaging effects of so dium on soil structure and permeabil ity. SAR is calculated using a formula that accounts for the chemical weight and charge of sodium, calcium, and magnesium. SAR values below 3 are generally considered acceptable for turfgrass sites (5). Survey results show that SAR values ranged from 0.04 to 2.76, with a median of 0.61 (Table 1). The survey indicates that 90% of the samples had SAR values equal to or be low 1.7 and 10% were equal to or below 0.12. All water samples in this survey had SAR values below 3.0.

11 Winter 2023 • Pennsylvania Turfgrass

800-873-3321 sales@ernstseed.com Native grass & wildflower seed https://bit.ly/ECS-RC Mike Kachurak ISA Certified Arborist PD-2739A 334 South Henderson Road King of Prussia, PA 19406 Office 610.265.6004 Cell 570.262.3612 mikek@shreinertreecare.com www.shreinertreecare.com Our warehouses are fully stocked and ready to meet your seeding needs with our extensive selection of turfgrasses and seeding supplies, ready to be prepared and delivered to suit your needs. LIFE IS COMPLICATED — SEED DOESN’T HAVE TO BE — WE MAKE SEED EASY. 797 Commerce Street Sinking Spring, PA 19608 Phone: 800-345-3344 SeedInfo@FMBrown.com

Bicarbonate, carbonate, and residual sodium carbonate (RSC)

Bicarbonate and carbonate concentrations are typically reported in irrigation water test reports for determining the potential for enhanced sodium-related soil permeability problems when SAR values are high, or when the formation of calcite in the soil or on the surface of putting greens, increasing soil pH, and iron chlorosis are of concern (3).

Bicarbonate concentrations in this survey ranged from 0 to 414 mg/L, with a median value of 87 mg/L (Table 1). Results show that 90% of the samples had less than or equal to 202 mg bicarbonate/L and 10% had less than or equal to 29 mg bicarbonate/L. Carbonate was detected in only 8 of 190 samples and ranged from 0 to 39 mg/L. Carrow and Duncan (2) stated that bicarbonate and carbonate concentrations in irrigation water are highly variable and suggested that bicarbonate may be a concern at levels above 120 mg/L, especially when sodium concentrations are high. However, when sodium concentrations are not high, bicarbonate values higher than 120 mg/L do not necessarily indicate that the water is of poor quality for irrigation. Approximately 40% of survey samples had bicarbonate values greater than 120 mg/L.

RSC values are generated by subtracting the sum of calcium and magnesium expressed in meq/L from the sum of bicarbon ate and carbonate in meq/L. A negative RSC value indicates that on an equivalent weight basis, there is more calcium and mag nesium in the irrigation water than bicarbonate and carbonate, whereas a positive value indicates that bicarbonate and carbonate in irrigation water have precipitated all or most of the calcium and magnesium ions (3). Positive values exceeding 2.50 meq/L suggest that the irrigation water is not suitable for use if the so dium and SAR are at levels that can cause soil permeability prob lems (3,5). The range of RSC values in this survey was −10.6 to 0.9 meq/L and the median value was −0.8 meq/L (Table 1). Based on the 90th and 10th percentile values found in this survey, the proposed normal RSC range for irrigation water in Pennsylvania is −0.1 to −2.4 meq/L. Only 12 of the 190 samples analyzed in this survey had positive RSC values and none exceeded 0.9 meq/L.

A secondary concern expressed by some turfgrass practitio ners is that the bicarbonate and carbonate in irrigation water will bind to calcium and magnesium, thus reducing calcium’s avail ability to turf and forming surface calcite or carbonate-cemented layers that reduce permeability in golf course putting greens. Although carbonate-cemented layering in soils may be problem atic in arid regions, research-based information to substantiate these concerns in turfgrass systems in cool, humid regions of the United States is limited (6,10). Research conducted at the Univer sity of Wisconsin involving 28 sand-based putting greens with dif fering geographical features found no evidence that bicarbonate from irrigation water formed carbonate-cemented layers or zones of accumulation (6). Given that none of the RSC values in survey samples exceeded 0.9 meq/L, and the limited research-based in formation concerning bicarbonate-induced calcium deficiencies and soil sealing problems in cool, humid regions such as Pennsyl vania and the surrounding states, the 120 mg/L upper limit for bicarbonate listed on many irrigation water test reports may be unnecessarily conservative.

Chloride

Survey results showed that chloride ranged from less than 1 to 221 mg/L, with a median of 26 mg/L (Table 1). 90% of the samples had chloride concentrations at or below 97 mg/L, and 10% were at or below 4 mg/L. The 4 to 97 mg chloride/L normal range is very close to the 0 to 100 mg/L desired range listed by Duncan et al. (3).

Conclusions

This survey aimed to establish a baseline profile of turfgrass irri gation water quality from nonamended and noneffluent sources in Pennsylvania that can be compared with water quality data from other geographic regions and future surveys in the Com monwealth, and to improve test report guidelines for samples submitted to water testing laboratories. Results show acceptable irrigation water quality according to published guidelines with some exceptions, including high values for sodium, TDS, and chloride, but these were less than or equal to 10% of the samples. Data from this survey were used to establish normal ranges for the 24 water quality parameters examined. Normal ranges for the quality parameters of turfgrass irrigation water in Pennsyl vania are likely to differ from those in other areas of the United States. In the case of pH, alkalinity, and bicarbonate, normal ranges should be expanded to account for the numerous water samples (> 45%) that exceeded the ranges listed in some water test reports. Normal ranges can serve as references for practitio ners and consultants when comparing the irrigation water quality used at one facility with the range of values generated from water samples collected throughout Pennsylvania.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the following individuals for collecting the water samples for this survey: George Skawski, Eric Kline, Danny Kline, Jeff Gregos, Don Lipandro, Robert Capranica, Tanner Del valle, Thomas Bettle, and Christopher Marra. Financial support for this research was provided by the Stanley J. Zontek Endow ment and the Pennsylvania Turfgrass Council.

Cover Story • continued 12 Pennsylvania Turfgrass • Winter 2023

References

1. Ayers, R. S., & Wescot, D. W. (1994). Water quality for agriculture. FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper 29 Rev. 1. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://www. fao.org/3/T0234E/T0234E00.htm

2. Carrow, R. N., & Duncan, R. R. (2012). Best management practices for saline and sodic turfgrass soils. CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.1201/b11186

3. Duncan, R. R., Carrow, R. N., & Huck, M. T. (2009). Turfgrass and landscape irrigation water quality. CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420081947

4. Gelernter, W. D., Stowell, L. J., Johnson, M. E., Brown, C. D., & Beditz, J. F. (2015). Documenting trends in water use and conservation practices on U.S. golf courses. Crops, Forages, and Turfgrass Management, 1(1), 1–10. https://doi. org/10.2134/cftm2015.0149

5. Harivandi, M. A. (1999). Interpreting turfgrass irrigation water test results. University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources Communication Services. Publication 8009. https://anrcatalog.ucanr.edu/pdf/8009.pdf

6. Obear, G. R., & Soldat, D. J. (2015). Soil inorganic carbon accumulation in sand putting green soils: I. Field relationships among climate, irrigation water quality, and soil properties. Crop Science, 56, 452–462. https://doi.org/10.2135/ cropsci2015.06.0341

7. Siwiec, S. F., Hainly, R. A., Lindsey, B. D., Bilger, M. D., & Brightbill, R. A. (1997). Water-quality assessment of the Lower Susquehanna River Basin, Pennsylvania and Maryland; design and implementation of water-quality studies, 1992–95. Open-File Report 1997–0583. U.S. Geological Survey. https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/ publication/ofr97583

8. Swistock, B. R., Clemens, S., Sharpe,W. E., & Rummel, S. (2013).Water quality and management of private drinking water wells in Pennsylvania. Journal of Environmental Health, 75(6), 60–66.

9. Tucker, C. S., & D’Abramo, L. R. (2008). Managing high pH in freshwater ponds. Publication No. 4604. Southern Regional Aquaculture Center.

10. Whitlark, B. (2014). Can water containing high bicarbonates seal off your soil? USGA Regional Update, West Region. United States Golf Association. https://archive.lib.msu.edu/tic/ usgamisc/ru/w-2014-12-02.pdf

11. Wurts, W. A. (2002). Alkalinity and hardness in production ponds. World Aquaculture, 33(1), 16–17.

13 Winter 2023 • Pennsylvania Turfgrass

PLAYING THE LONG GAME

Overcoming Supply Chain Challenges in Turfgrass Management

By Julie Holt, Managing Editor, Leading Edge Communications

A version of this article was originally published in New England BLADE, Winter 2022 issue. It is reprinted with permission.

Turfgrass managers have always been known to have a great deal of resilience in the face of unexpected challenges. Just take a quick glance at the weather patterns of the past five years and you’ll find extremes in all directions – record heat, record cold, drought, record snowfall, floods and even tropical storms. And don’t forget weeds, pests, and disease. But if you also visit the golf and sports news archives, you’ll find that sports events carried on, as did home lawn maintenance, mostly uninterrupted.

As ever, turfgrass professionals show up and figure it out. Through hard work, cooperation and ingenuity, each of those challenges have been overcome and the resilience of those pro fessionals has been proven over and over.

Now, entering another winter season, and looking ahead to the busy spring season, golf course superintendents, sports field managers, sod producers, and lawncare operators are working to solve yet another wrench in the plans: supply chain disruption. What started as a result of the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic has now firmly set in as status quo, at least for the foreseeable future. These delays have been affecting the turfgrass industry (and many others) for nearly two years, and the light at the end of the tunnel isn’t visible just yet. However, almost as soon as this challenge arose, professionals in all segments of turfgrass man agement began looking for answers and work-arounds to keep the industry moving forward.

A Chain is Only as Strong as its Weakest Link

While COVID was the domino that set the reaction in motion, a labor shortage was a well-established challenge even before raw material shortages resulted in production delays, which then cre ated an environment ripe for higher cost and limited availability of products ranging from bottled water to tractor parts. In effect, each link in the supply chain has been weakened. When pan demic lockdowns prevented workers from all parts of the supply chain (Figure 1) from maintaining production, the process nearly ground to a halt.

The reopening of those lines was sluggish, and certainly not linear. In the nearly three years since the beginning of the pan demic, overseas lockdowns have ebbed and flowed, creating an unpredictable pipeline bottleneck. The ultimate result has been soaring prices and low or nonexistent stock of products and tools.

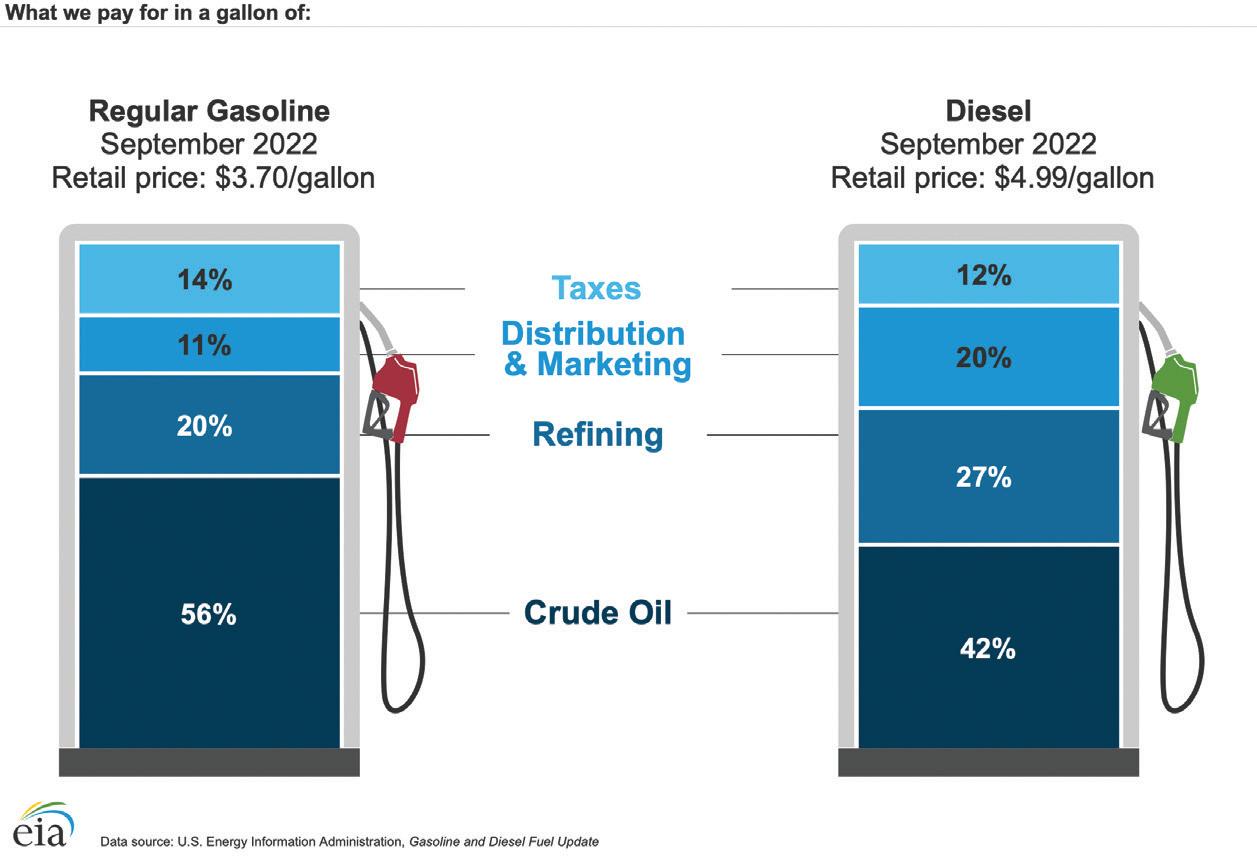

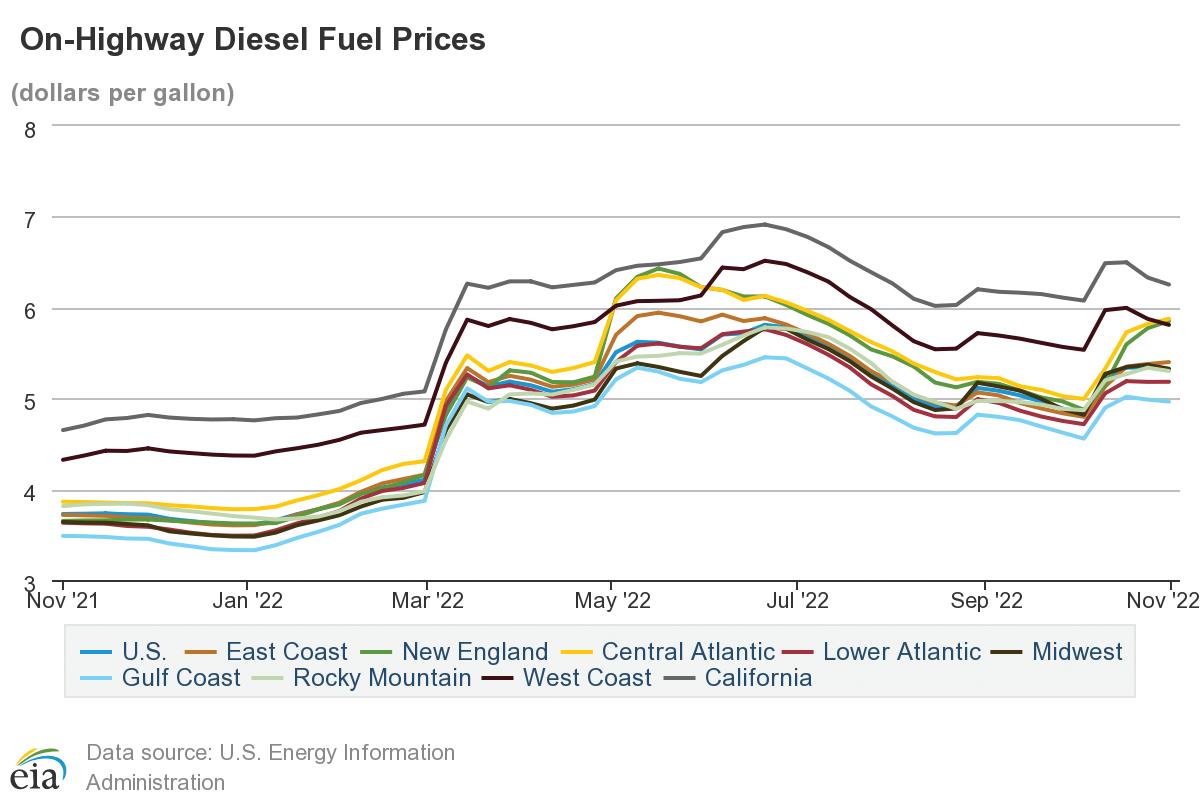

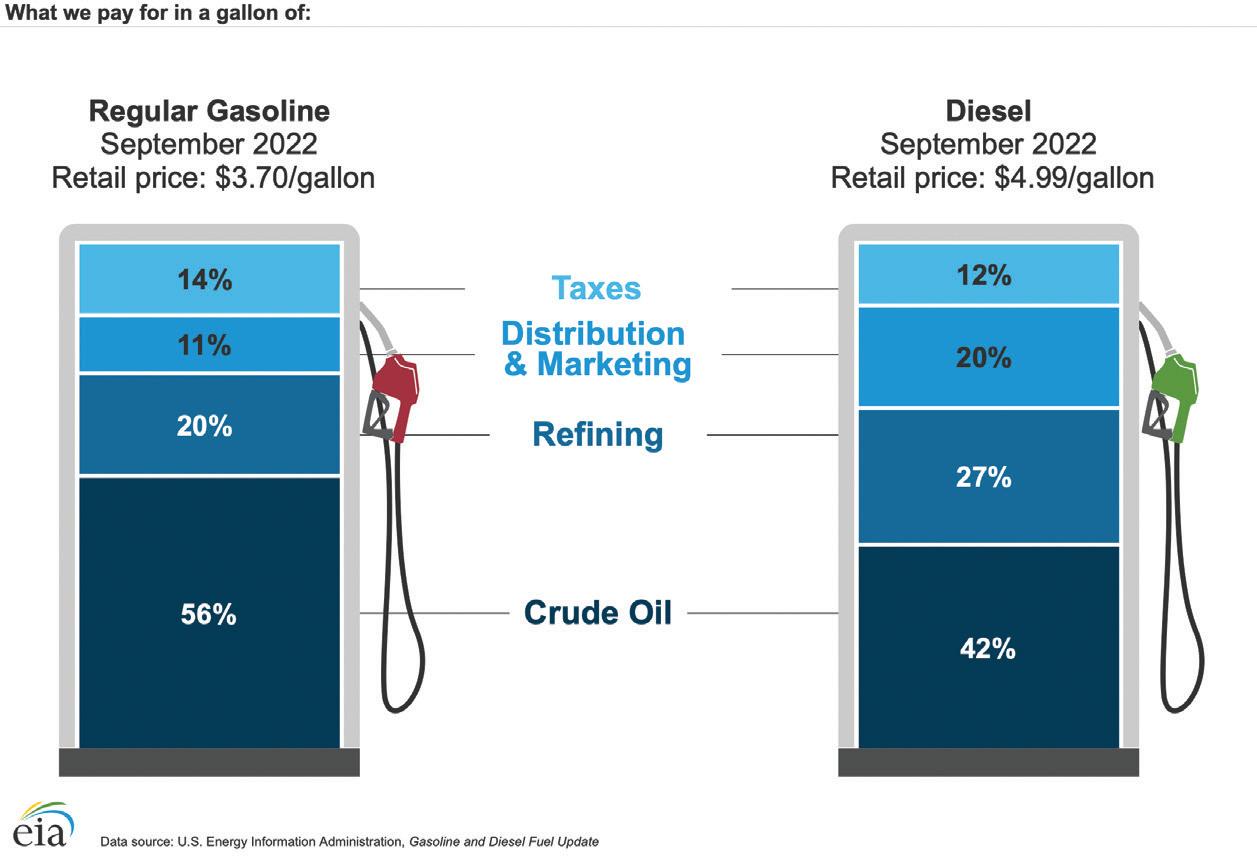

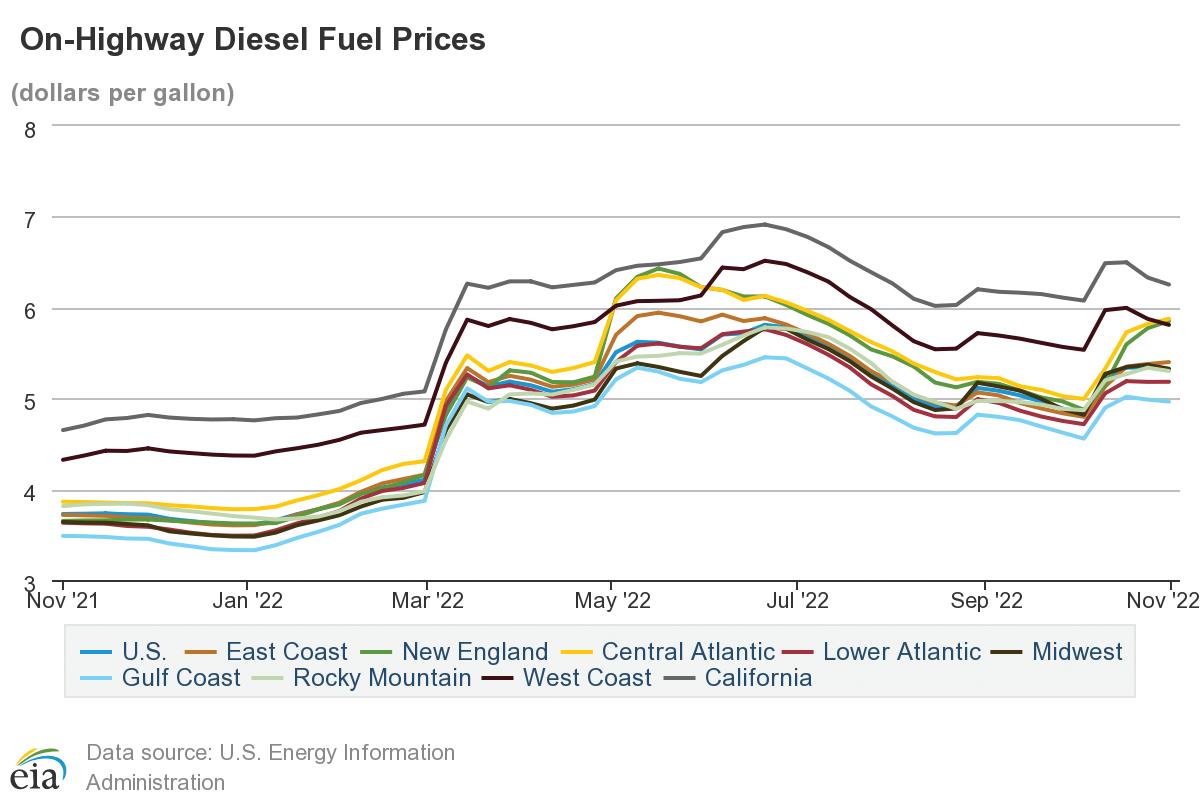

Regulation and policy locally and globally certainly play a role in the supply chain, and adaptation to the current climate has been sluggish. The latest challenge that has resulted from these fac tors is a looming diesel shortage, which certainly will cause price increases that will be passed along to the consumer (Figures 2, 3).

A Proactive Solution

The supply chain problem is well-documented, but what about the solution? Every distributor, supplier and salesperson echoes the same line: plan ahead and be proactive. What does this entail, exactly?

Ian Lacy, Lead Project Advisor at Tom Irwin emphasizes that turfgrass managers must place great emphasis on a forward fore cast. Understanding that equipment that formerly would have taken three months to arrive may now be closer to a year means you must take careful inventory of your existing product and equipment and forecast two to three years out, rather than one year. This approach requires diligent planning, but if this is to be the “new normal,” this type of planning must be our standard. “To repeat the old cliché, we have to ‘prepare for the worst, but hope for the best’,” Lacy shares.

Another shift in procedure that mitigates for shipping issues is looking for product closer to home. Understanding the many vari ables at play (see sidebar box), eliminating the need to have prod uct shipped from overseas can speed the arrival of some products.

Adam Ferucci, Sales Representative at Read Custom Soils reit erates the need to plan ahead, but also to continuously monitor prices and delivery times. Asked how his customers have had to adapt, he says they must “be more proactive and give proper lead time to deliver,” and “reach out for quotes more frequently to be able to budget for price increases.”

FIGURE 1: Simplified Supply chain.

Feature 14 Pennsylvania Turfgrass • Winter 2023

RAW MATERIALS MANUFACTURER RETAILER SUPPLIER DISTRIBUTOR CONSUMER

While suppliers can’t magically make stock appear, they can keep their customers informed and encourage them to be forward thinking. Ian Lacy shared an example of just how frustrating this situation can be. “We helped a client rebuild a baseball field. The weather slowed us down, but we had time. But then the supply chain slowed us down. We ordered the part, a simple water meter, and what should have been delivered in three weeks, was up to 16 weeks. The contractor had already seeded the outfield, but we had no water. This one small part that only took three hours to actually install, set us back months.” Nearly every turfgrass professional can tell a similar story.

But as this industry does, we’ve come together to share solutions that help to ease the burden of this supply chain bottleneck. Professionals in all industry segments have put their heads together to innovate and educate their peers, and even competitors, on solutions to this challenge.

Mark Casey, Sales Territory Manager in Massachusetts for Finch Turf shares his transparent communication process with his customers. “To be helpful and to best serve customer interests, the conversations have substan tially changed. We are recommending they take stock of their inventory today, draw a plan to secure their fleet for the current and coming season and have a plan B for all scenarios if a machine goes down. Managers need conti nuity of operations and now aren’t always able to count on a dealer loaner or demo machine support, which in this climate have been fewer and limited. The purchase of used & refurbished machines have become a popular, viable, and more available option. We are helping more customers assess fleet strength and provide long term plans for replacement.”

The current supply chain crisis may have taken the industry off guard, but one thing is certain – turfgrass industry professionals are well-equipped to adjust, reevaluate and find winning solutions.

15 Winter 2023 • Pennsylvania Turfgrass

FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO SUPPLY CHAIN CHALLENGES COVID-19 Pandemic Response Labor Shortages Raw Material Shortages Freight Cost Production Delays Port Congestion Policy / Regulation Natural Disasters

FIGURES

2, 3: Gas and diesel price trends contribute to higher shipping and freight costs. Source: https://www.eia.gov/petroleum/gasdiesel/

KAFMO Marks 25 Years of Little League Baseball® World Series Partnership

is a double anniversary year – Little League Baseball® World Series cel ebrates 75 years of playing ball and the Keystone Athletic Field Managers Organization (KAFMO), celebrates 25 years of providing field maintenance assistance for the World Series in Williamsport. The Little League World Series has become a landmark event. Every August, teams of 11- and 12-year-old players from all over the world converge on the Little League complex in South Williamsport, PA with high hopes. The event has grown from 16 to 20 teams and in 2022 it was Hawaii’s Honolulu Little League who bested Cura çao 13–3 to become the Little League Baseball® World Series Champions. Television coverage of every game on ABC/ESPN has sent the numbers of spectators into the millions. Of course, the players, coaches, and umpires on the field are the focus of camera operators and television production crews. But long before they can “Play ball,” the field must be ready and safe for play. That task is carried out by members of KAFMO.

History

KAFMO’s history is closely intertwined with that of Little League Baseball®. At about the same time that KAFMO founder Don Fowler was bringing together his first group of

athletic field professionals, Little League leaders decided to renovate Lamade Stadium for the 50th Little League World Series. “KAFMO members were asked to help with the job and we stepped up,” he said with pride in a 2020 look back over his career. In recent years, Don’s son Jeff has taken over the job of coordinating the volunteers who come for the Series. Over time, as the event has become bigger and more popular on TV, Don’s handwritten list of volunteers has grown to a database of more than one hundred people from twenty-one states who come to help – and need to be housed, fed, and assigned to work crews.

Volunteer Professionalism

Jeff Fowler, Penn State Cooperative Extension Turfgrass edu cator and KAFMO Board member, works with Little League staff to make sure every volunteer is taken care of. He gives them major credit for their hard work and professional ap proach. “The chapter has been honored to assist Little League Baseball® with field preparation for 25 years. The crew that we assemble for the Little League World Series is second to none. Not only do they have the fields at the forefront of their minds, but their professionalism is supreme.”

KAFMO grounds crew volunteers are active members of SFMA (formerly STMA). The volunteers arrive before the se ries begins, level the playing surface, edge the fields, and resod any areas that are worn from summer play in preparation for the twelve days of the Series. Every night the crew removes the lines, grooms and waters the infield, brooms the edges of the grass, repairs clay in the home plate circle and on the pitcher’s mound, grooms the warning track, and has the field ready for the next day. Some volunteers stay for the entire two weeks;

Secretary

Keystone Athletic Field Managers Organization 1451 Peter’s Mountain Road Dauphin, PA 17018-9504 www.KAFMO.org • Email:

16 Pennsylvania Turfgrass • Winter 2023 2022

Contact: Dan Douglas, President Phone: 610-375-8469 x 212 KAFMO@aol.com Contact: Linda Kulp, Executive

Phone: 717-497-4154 kulp1451@gmail.com

KAFMO@aol.com

Wetting the Infield Brooming 1st Base Line Almost Game Time BETWEEN THE LINES

others help out for a few days. People use their vacation time and leave their own work and families to come to the Series to assist with field preparations. Why do they do it?

Many Rewards

“Being part of a group of professionals who are providing top quality playing fields for the World Series is an honor,” says Bill Boll, retired Assistant Facilities Director for York Suburban School District in York, PA. Bill has been volunteering at William sport since 2009. “I prepare and maintain the pitching mound in Lamade Stadium with Jim Welshans, as well as any other tasks required on the fields and practice fields. The excitement and energy generated by the players is very rewarding. It never gets old and it is why I come back each year. An unexpected reward I’ve experienced over the years at Williamsport is the friendships and bonds developed with other crew members from all over the country. Many have become life-long friends. It’s like family.”

Volunteer Dan Miller, Director of Parks and Recreation for North Huntingdon Township, agrees. His annual tradition of assisting at Williamsport started in 2015 and for the past eight summers, each one has been a memorable experience. “Sharing knowledge, meals, and laughs with ‘turf and dirt’ friends giving their time where baseball played by kids is ‘pure’ keeps me com ing back,” he says. “Many hands make light work.”

Led by Leaders

“Rob and Jeff manage our duties and schedules in a way that has us all proud to represent Little League,” says Miller. “We are led by leaders.” Rob is Rob Guthrie, Head Groundskeeper at the Little League complex. “The volunteers bring with them a wealth of knowledge and experience of turf and field maintenance. Most volunteers are able to jump in and begin working seamlessly in our current field maintenance operation,” he says. His number one priority is providing a safe playing surface year-round for the kids to play on. It is his dedication throughout the year that lays the groundwork for the intense 40 games over twelve days in Au gust. A safe field requires year-round attention and the wear and tear of the Series takes a heavy toll on the fields in mid-August. “The volunteers play an important role in putting the finishing touches on the stadiums and making sure they are safe for play. I rely heavily on them for game day preparation and without them a world series event would not be possible,” says Guthrie.

The KAFMO volunteer grounds crew has good reason to be proud of what they accomplish during the Series. Many of the crew members have been attending for 15 years or more. Some even bring their own children with them to help out, a welcome sight to all KAFMO members. As Jeff Fowler, whose own family has a multi-generational KAFMO/Little League Baseball® World

tradition,

of sports turf managers are made!” 17 Winter 2023 • Pennsylvania Turfgrass WWW.PROGRESSIVETURFEQUIP.COM 800.668.8873 Better Built. Quality Results. Period. Quality built in North America and supported by a world-wide Dealer network. Tri-Deck cutting widths: 12’, 15.5’, 22’*, 36’* Roller Mower cutting widths: 65”, 90”, 10.5’, 12’, 15.5’, 22’*, 29.5’* Contour/rough finishing mower: Pro-Flex™ 120B 10’ cut TDR-X™ roller mower 10.5’ cut Progressive Turf builds the right mowers and rollers for any field. For over 30 years they have set and re-set the standards in commercial grade mowing equipment. Contact your Progressive Dealer to find out why Progressive products are outstanding in any field! * available with bolt-on galvanized deck shells

Series

puts it, “That is how the next generation

Contour / Rough Finishing Mowers

field, Park and Estate Mowers

Turf Grass Production Mowers

Sports

Research Update from The Turfgrass Entomology Laboratory

It

has been one of the quieter turfgrass insect pest years I can remember – at least in the last eight years since I have been at Penn State. Annual bluegrass weevil (ABW) populations re main low at most sites across Pennsylvania, fall armyworm did not have back-to-back outbreak years, and white grub populations were likely negatively impacted by the extended drought-like conditions.

Despite the low pest pressure year, the Turfgrass Entomology Labo ratory has been busy building for the future. This fall we welcome two new graduate students: Rowda Altamimi and Stokes Aker. Rowda re cently completed a master’s degree at the University of Florida working on biological control of citrus pests. She will be bringing her experi ence in insect behavior to help us better understand ABW-moisture re lationships, as well as develop more sustainable controls. Stokes comes to us from the University of Maryland where he provided technical sup port of numerous projects related to Emerald Ash Borer. His masters project will focus on the effects of spring insecticides on non-target arthropod populations and predator behavior.

Congratulations to current PhD candidates, Audrey Simard and Garrett Price for recent awards and scholarships. Audrey won the student oral presentation competition at the International Turfgrass Society meeting in Copenhagen, Denmark in July. In August, both were awarded Entomology Department scholarships. Audrey was awarded the Duke Memorial Scholarship and Garrett the Paul Heller Memorial Scholarship, named in honor of my colleague and predecessor. I think Dr. Heller would be quite proud of both.

DIGITAL MARKETPLACE: Scan the QR Code to learn more about this company.

Penn State News 18 Pennsylvania Turfgrass • Winter 2023 SPECIALIZING IN BENTGRASS SOD FOR GREENS, TEES, & FAIRWAYS FINE AND TALL FESCUE REGULAR AND SHORTCUT BLUEGRASS KEVIN DRISCOLL CELL: 609-760-4099 OFFICE: 856-769-9555 KDRISCOLL@EASTCOASTSOD.COM JANUARY 26, 2023 Northeastern PA Golf, Lawn, Landscape and Sports Turf Conference The Woodlands Inn and Resort Wilkes-Barre, PA FEBRUARY 2, 2023 Eastern PA Golf, Lawn, Landscape and Sports Turf Conference Shady Maple Conference Center East Earl, PA For additional details, visit Save These Dates! paturf.org

Specializing in Aggregates for the Sports Turf Industry Bunker Sands | Topdress Sands | Divot Mixes Rootzone Mixes | Stone Products MitchellSand.com | 856-327-2005

WWW.STECEQUIPMENT.COM

V. Halyard – Storylounge Photo

V. Halyard – Storylounge Photo