6 minute read

Cover Story

State of Matters: Indicator Weeds

By Max Schlossberg, PhD

All original images and no more than zero artificial intelligence resources were utilized in preparation of this article.

While not a trained weed scientist, I take every opportunity to enrich my understanding of the integrated pest management (IPM) subdiscipline of turfgrass science. I’m also fortunate to teach two graduate level courses to agricultural and environmental plant science students here at Penn State. Thus, I’m a lucky benefactor of a veritable, ‘Cheesecake Factory-sized’ menu of current plant science field research every year. A significant fraction of which relates to Weed Science, largely via graduate students supervised by Drs. John Wallace, Carolyn Lowry, and Caio Brunharo.

Pennsylvania agronomic producers typically manage annual species like corn, soybean, and small grains. I’ve learned that within these production systems, weed management strategies focus keenly on reducing the weed seedbank. Such control strategies target specific weeds renowned for profuse seed production (and subsequent proliferation).

This was an intriguing revelation. Until now, my callow appreciation for a plant species’ success, or fitness, had hinged on its range-expanding ability; e.g., dispersion of the dandelion seed by wind (anemochory), or dispersion of sticky burs by animals (epizoochory). But, as it turns out, certain inherencies make row crop production more susceptible to weeds prioritizing prolific seed production and copious local distribution, rather than creative dispersive mechanism(s). These inherencies include annual field preparation and Spring planting.

Now a significant weed seedbank exists in nearly all soils. Yet, turfgrass managers steward perennial systems devoid of the annual, optimal-growing-condition window for its seedbank of wannabe upstarts. Thus, whether viable weed seeds in the resident seedbank germinate and actively encroach on the perennial turfgrass quite frankly depends on the appropriateness of the selected turfgrass species/cultivar and current culture and use.

Paddy rice production is a long-used analogy of my integrated pest management (IPM) talks that may prove useful here.

Every Fall, exceptional yields of rice are harvested from dryland fields across the south-central US. So, if rice is neither an aquatic plant nor classified as an obligate wetland species, then why do we associate rice with paddy production? Well, because when planted in a wetland or paddy, rice dependably outcompetes aquatic and other anoxia-tolerant plants while supporting respectable grain yield. Thus, in many places, it is IPM that justifies paddy production of rice.

Some common lawn-invading plants such as annual bluegrass, dandelion, and quackgrass (Fig. 1) are too tenacious and versatile of weed species to be associated with a single edaphic, cultural, or environmental advantage. But, just as rice has unique tolerance for anoxic soils, other plants express singular tolerance for other edaphic, cultural, or environmental stresses.

In fact, numerous plants are capable of proliferating in competition with maintained turfgrass under one or more edaphic, cultural, or environmental circumstance(s). These species are often curated into lists of indicator weeds. Proliferation of an indicator weed in your resident turfgrass may just be, as the band Spirit once sang, ‘...nature’s way of telling you...something’s wrong.’

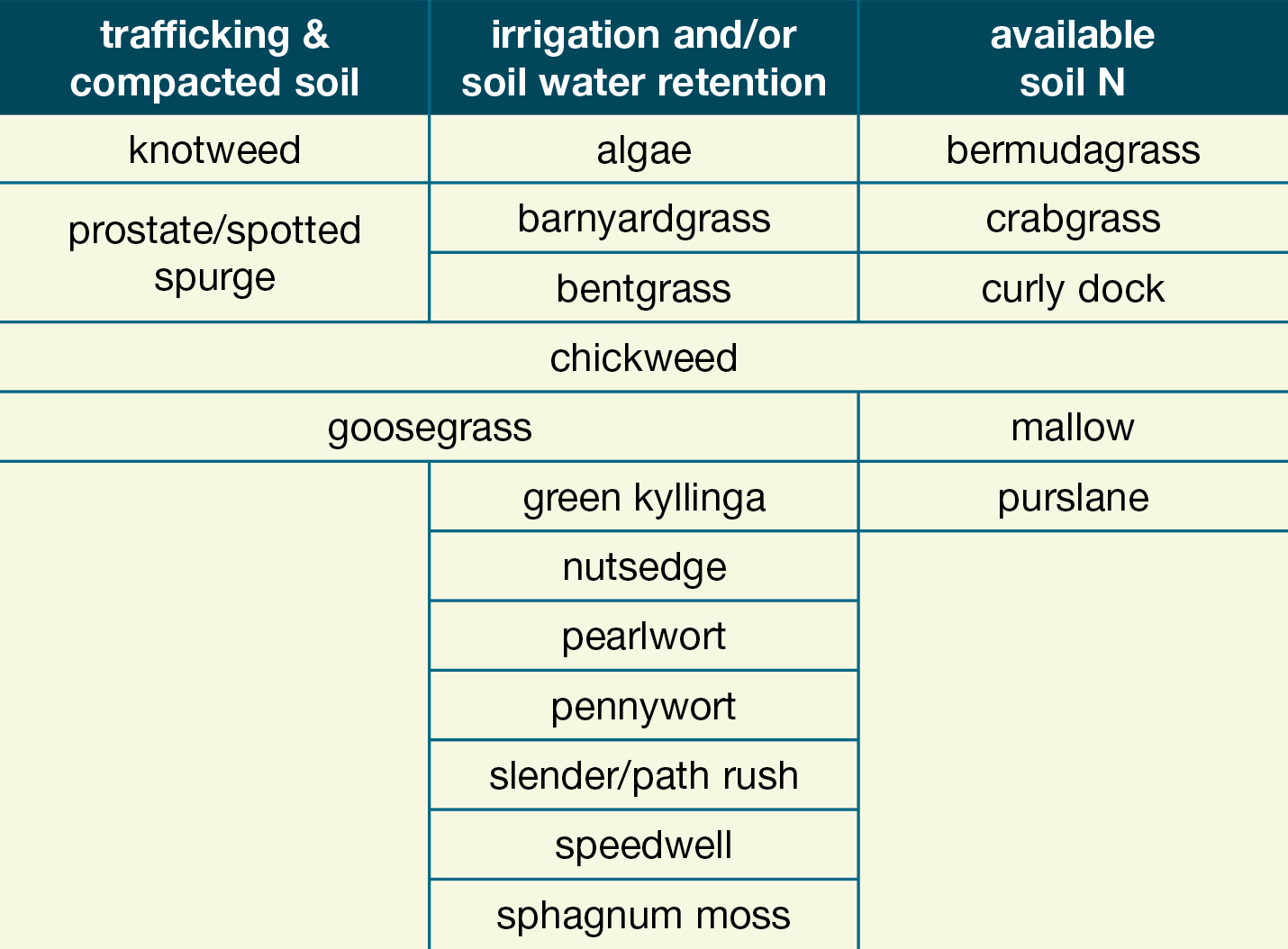

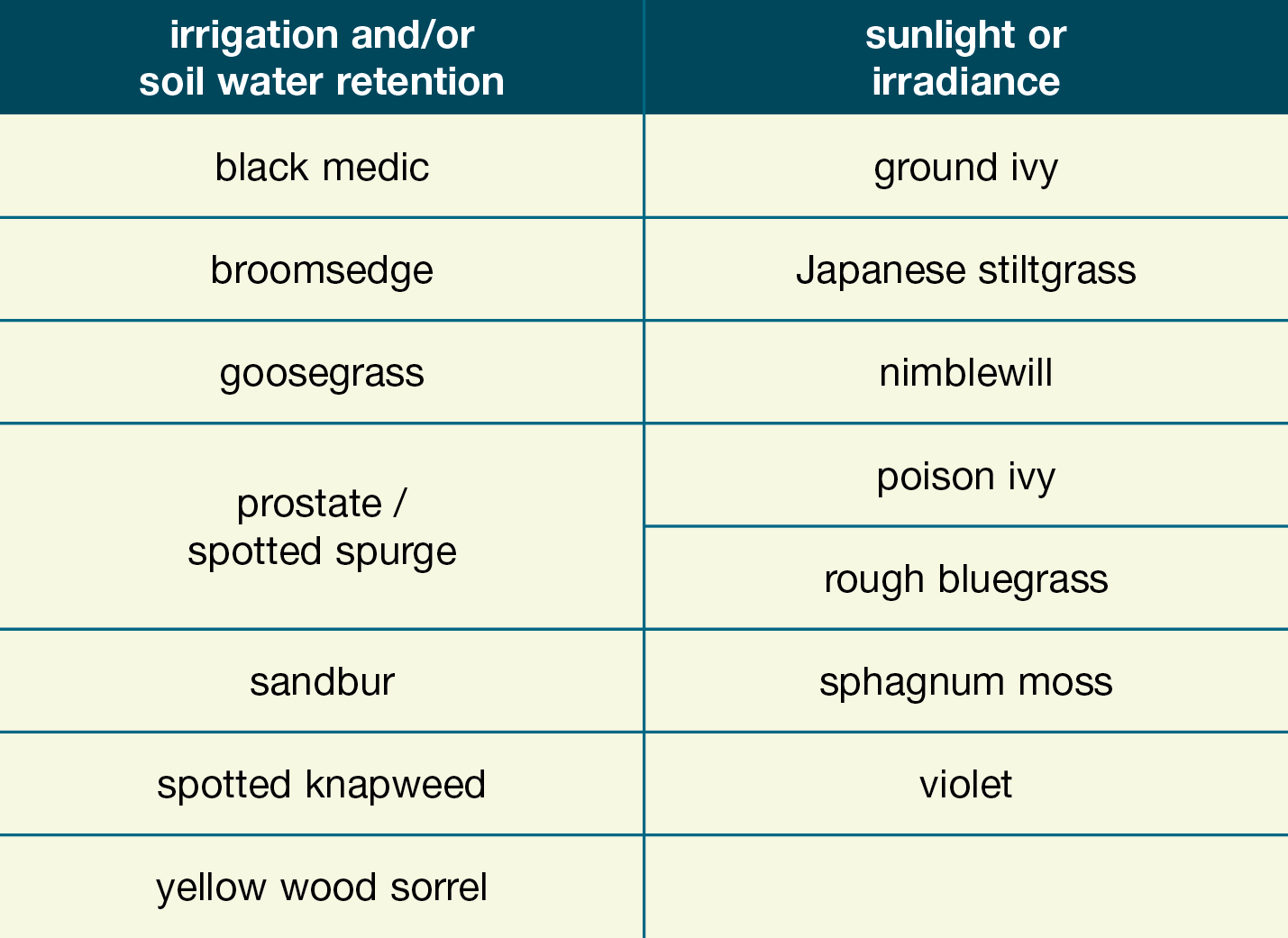

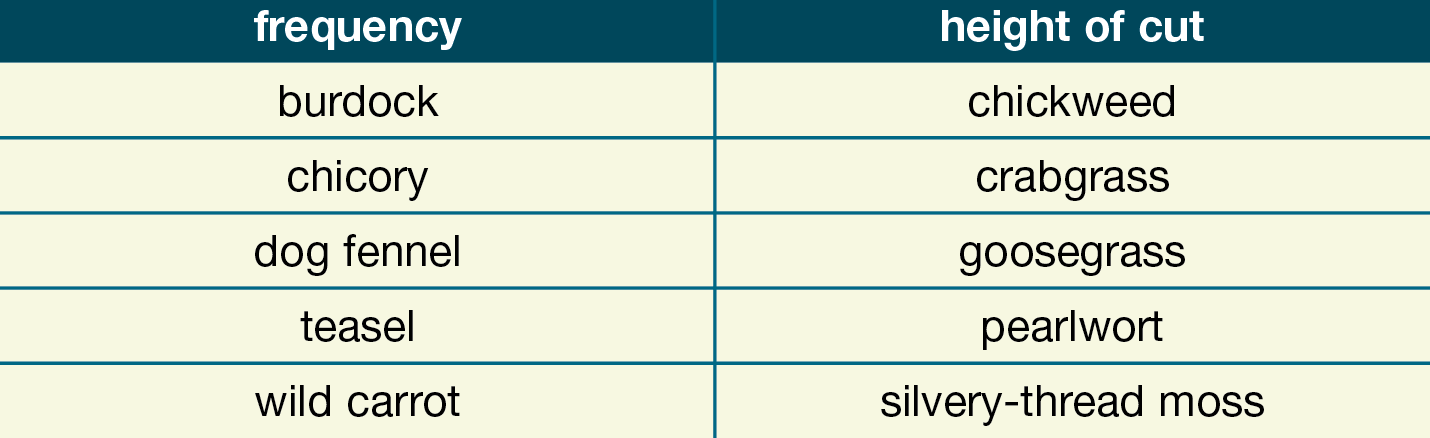

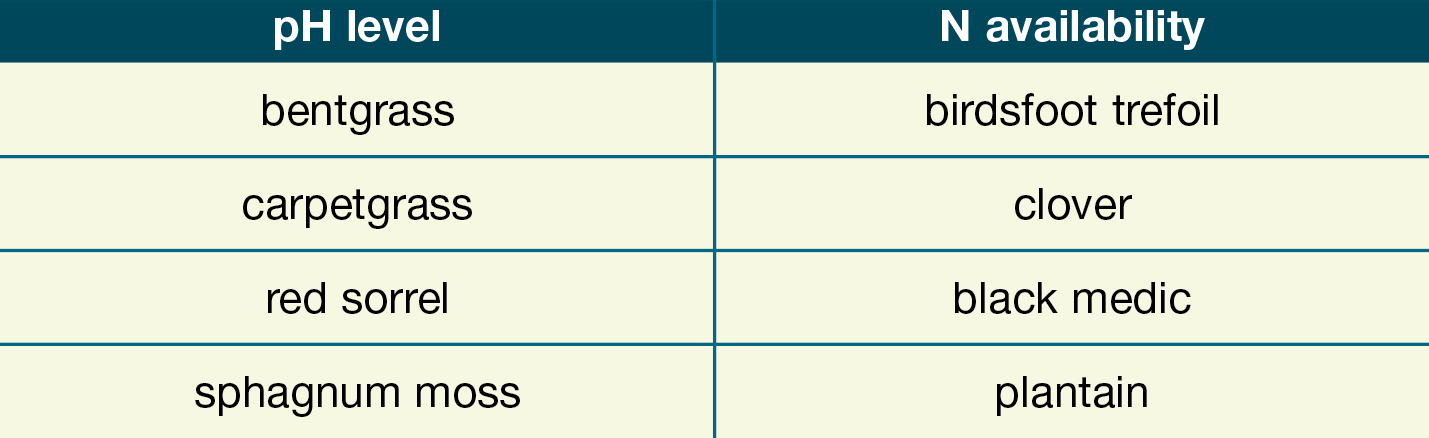

On that same note, these curated lists are simply guides to help managers diagnose problems and devise strategies. Some indicator weeds, e.g. yellow nutsedge, are growth-stage specific. Nutsedge seedlings are well adapted to moist soils and included in Table 1 as a weed indicating excessive irrigation and/or soil water retention. However, once established, nutsedge demonstrates staunch drought resistance and quickly spreads by vigorous rhizomes. The lists provided as Tables 1 through 4 are not all-inclusive.

Weed scouting is a critical component of turfgrass IPM. Onsite personnel are ultimately responsible for proper identification of weed species, ideally not relying on a photo and one smartphone app. Experience should remind us that certain perennial weeds are more easily identified in certain seasons. For example, I scout my research Kentucky bluegrass area for rough and annual bluegrass before the first mow every Spring. Early Spring is also when I assess the extent of sphagnum moss proliferation in the shadiest parts of my home lawn.

Late Summer presents another window of opportunity. While systematic preemergent herbicide treatment most effectively limits Summer annual competition, late Summer is when those pesky perennial weeds present their reproductive parts and make identification easy.

If two or more RELATED indicator weed species are present at each site, then evaluate the microclimate, landscape position, and sample the soil to a 6" depth. Considering recent weather conditions and/or irrigation applied, is the soil drier or wetter than you expected? Submit the soil for routine fertility analysis, being sure to select the proper turfgrass species or mixture.

Efforts to reverse the condition weed encroachment indicates are recommended, but not certain to control the weed. This is particularly true for perennial weed species. But if the edaphic, cultural, and/or environmental conflicts are dismissed in preference of herbicide treatment, then the weed problem is only controlled over the short run. Without meaningful sitework to reverse the resident limitations, the weeds will likely return. So, once you’ve obtained all results, follow soil test recommendations and rectify the conditions indicated by tree pruning/removal, drainage installation, introducing a new species/cultivar, and/or culture (e.g., adjusting height of cut, irrigation scheduling, etc.).