7 minute read

Off With Their Heads: Phorid Decapitating Flies to the Rescue

By Jason Oliver, Karla Addesso, and Nadeer Youssef, Tennessee State University, Karen Vail and Pat Parkman, University of Tennessee and Joshua Basham and Steve Powell, Tennessee Department of Agriculture

"Off with their heads!” was a favorite snap of the illtempered Queen of Hearts in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland story. But in real life, the equally infamous imported fire ant (Solenopsis spp.) has similar head-cutting enemies in ant-decapitating flies in the family Phoridae. The U.S. Department of Agriculture found this fire ant nemesis while searching for natural enemies in South America, which is the native range of Solenopsis ant species. Decapitating phorids in the genus Pseudacteon are small, gnat-sized flies belonging to the ‘hump-backed’ fly family. The family name describes the enlarged buffalo-like raised back, or thorax, of these flies (Fig. 1).

Advertisement

FIG. 1. A female Pseudacteon curvatus phorid fly. Note the ‘hump-backed’ characteristic of these flies and the curved egglaying ovipositor on the tail-end of the fly, which relates to the ‘curvatus’ species name that means bent, hooked, or curved in Latin. (Photo by Nadeer Youssef, TSU)

FIG. 2. An adult phorid fly about to inject an egg in the thorax of a fire ant worker (image courtesy of Sanford D. Porter, USDA-ARS, Center for Medical, Agricultural and Veterinary Entomology, Bugwood.org).

Phorid flies are attracted to chemical signals produced by fire ants foraging for food (trail pheromones) and when colonies are disturbed (alarm pheromones). During a successful phorid fly attack, an egg is injected into the thorax behind the head of worker fire ants (Fig. 2). The actual egg injection occurs within just a fraction of a second; so fast the flies do not land during the process. Many ant-decapitating phorid fly species have uniquely shaped egg-laying ovipositors that are often reflected in their corresponding scientific species names (Fig. 3). Like a ‘lock and key’ system, the ovipositor shape also matches the specific location on the ant thorax where the adult female fly of each species prefers to lay eggs. After eggs hatch, the fly larva moves to the head capsule of the fire ant and begins to feed and grow. The larva eventually kills the ant, after which the head subsequently falls off of the ant body yielding the common name as ‘decapitating flies’ (Fig. 4A). After development, the adult fly exits the ant head by pushing through the mouthparts (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 3 A. Egg-laying ovipositor of P. curvatus. (Photo by Nadeer Youssef, TSU)

Fig. 3 B. Egg-laying ovipositor of P. cultellatus. (Photo by Nadeer Youssef, TSU)

Fig. 3 C. Egg-laying ovipositor of P. obtusus. (Photo by Nadeer Youssef, TSU)

Fig. 3 D. Egg-laying ovipositor of P. tricuspis. (Photo by Nadeer Youssef, TSU)

Fig. 4 A, B. A: A decapitated worker fire ant. B: An adult phorid fly emerging through the mandibles of a decapitated ant head (emerging fly image source: USDA-ARS Photo Unit, USDA Agricultural Research Service, Bugwood.org).

Fig. 4 A: A decapitated worker fire ant.

Fig. 4 B: An adult phorid fly emerging through the mandibles of a decapitated ant head (emerging fly image source: USDA-ARS Photo Unit, USDA Agricultural Research Service, Bugwood.org).

While developing, the fly larvae can modify the behavior of their ant host, causing the ants to exit the colony and seek out sheltered locations, like under leaves, to die. The manipulation of the ant to perform alternate behaviors has been referred to as ‘creating zombie ants.’

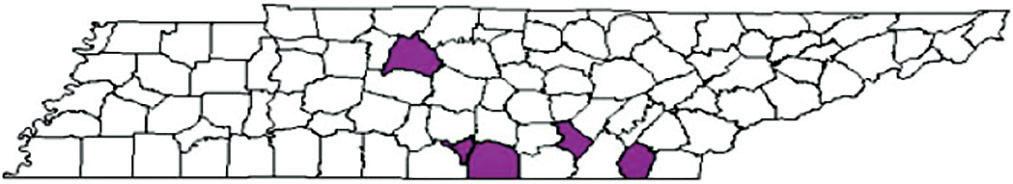

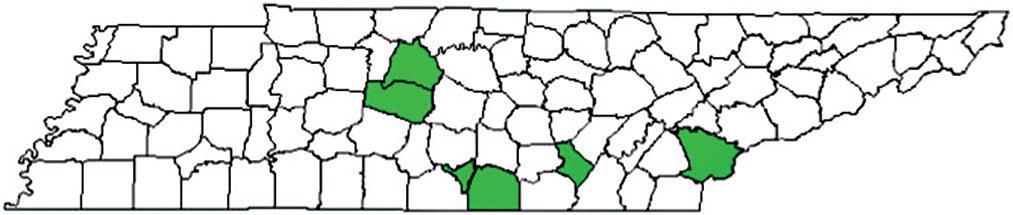

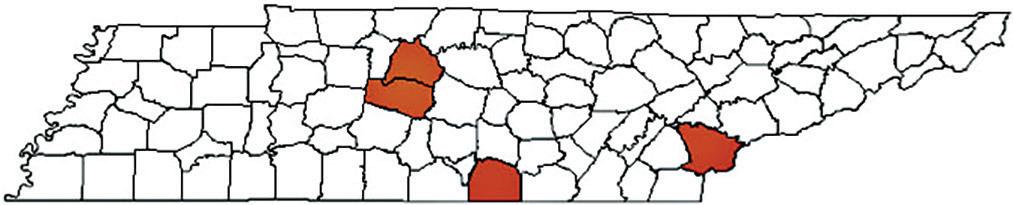

There are more than 20 phorid species in South America that are known to attack fire ants in the genus Solenopsis. After extensive testing to ensure the flies would not pose a threat to other insects, humans, or animals, the USDA has approved six phorid species for release in the United States (Table 1). From 1999 to 2017 and in cooperation with USDA-ARS and USDA-APHIS, we have released four of these fly species in Tennessee (Figs. 3 and 5 A-F, Table 1). Tennessee release locations of the four species are depicted in Fig. 6.

Although the USDA phorid release program ended in 2017, we are presently involved in efforts to determine establishment success of these fly species in Tennessee. Pseudacteon curvatus is now established statewide (Fig. 1). Each of these fly species offer different potential benefits. For example, smaller fly species tend to attack smaller worker fire ants and vice versa (Table 1). Since fire ant workers within a colony vary in size (Fig. 7), it is valuable that a range of fly species with different ant size preferences are available to attack ants. These fly species also can vary in their preference for red or black imported fire ants or their hybrid (all of which are found in Tennessee), the time of day they attack, and the location of attack, which may occur at disturbed mounds or along foraging trails (Table 1). Because each phorid species contributes a different ‘service component’ to fire ant management (i.e., niche specialization), it is important to establish as many phorid species as possible within a given area to maximize the effect of their management benefits against fire ants.

FIG. 5 A: Phorid fly attack boxes at the USDA-ARS Starkville, MS rearing facility.

FIG. 5 B: Individual attack trays with cups that raise and lower on timers to expose vulnerable hiding ants to flies.

FIG. 5 C: Collecting fire ant workers with a stick.

FIG. 5 D: Tapping collected fire ant workers into a bucket.

FIG. 5 E: Concentrating collected fire ant workers in a box for shipment to the phorid attack facility.

FIG. 5 F: Releasing parasitized worker ants back at their original home colony in Tennessee.

FIG. 6. County locations in Tennessee of the different phorid fly species released and total estimated numbers of flies released in the state. P. curvatus (~47,656 flies)

P. tricuspis (~9,392 flies)

P. obtusus (~53,449 flies)

P. cultellatus (~64,713 flies)

There are multiple benefits offered by phorid flies. One direct benefit of phorid flies is they kill fire ants, but only at a rate of about 3% of the colony at any given time. Therefore, phorid flies will not eliminate fire ants because all biological control agents require some level of their host to be present to sustain the beneficial species. Perhaps a greater potential benefit provided by phorid flies is their ability to harass fire ant workers during ant foraging activity, which reduces access to food. In the same way that nursery plants need water, sunshine, and soil nutrients to grow and thrive, a fire ant colony must collect food resources for the colony to persist and grow. Fire ant colony members include the queen, eggs, larvae, pupae, worker ants, and reproductioncapable progeny of the queen, called ‘reproductives’ (Fig. 7). The reproductives are a special caste of ants that serve to establish new colonies and spread the fire ant species by periodically leaving the colony during mating flights. Only large mature colonies will gather sufficient resources to produce reproductives. By harassing foraging workers, phorid flies may functionally reduce or limit colony growth and reproductive outputs of fire ants. Reducing access to food resources by phorid flies would be enhanced in areas with other aggressive ant species competing for the same food resources. Because fire ant workers can detect phorid fly attacks, the presence of phorid flies also reduces the time that colonies will remain agitated after mound disturbance. If you have experienced multiple fire ant stings after disturbing a mound (like the individual in Fig. 8), you will appreciate phorid flies for their help in chasing the ants back into the mound. Finally, it has been speculated that phorid flies may enhance the transmission of some fire ant pathogens. For example, it is possible the phorid ovipositor used to inject eggs may serve a dual role as a ‘dirty hypodermic needle’ spreading disease among colony members.

FIG. 7. Variation in fire ant worker sizes is typical in colonies.

FIG. 8. Results of an unfortunate encounter with red imported fire ants. Image source: Murray S. Blum, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org.

Fire ants continue to spread northward in Tennessee, partially or completely infesting 66 counties, thereby potentially impacting about 4.9 million people across an area greater than 18 million acres (Fig. 9). All of the primary middle Tennessee nursery growing counties are now infested. Imported fire ants and their hybrids have achieved all of this range expansion in just the 32 years since their first confirmed natural entry into Hardin County in 1987. Unfortunately, fire ant presence in the nursery-growing areas adds cost and management activities to growers (Fig. 10 A, B), who must apply required regulatory treatments to certify nursery stock for shipment out of the Federal Quarantined area (Fig. 9). Hopefully, phorid flies may be one component of a larger management plan for reducing the fire ant problem in Tennessee. One significant benefit of the flies is they are ‘free and self-maintaining’ once they are established, so maybe the Queen of Hearts was right after all — “Off with their heads!”

FIG. 9. 2018 Imported Fire Ant Quarantine Area (Image courtesy of the Tennessee Department of Agriculture). Red areas = Imported Fire Ant Quarantine Area.

FIG. 10 A: Nursery plant with a fire ant colony at the base.

FIG. 10 B: Spreading granular insecticide in a nursery for imported fire ant control.