The Official Publication of The Tennessee Nursery and Landscape Association

The Official Publication of The Tennessee Nursery and Landscape Association

Biological Control in the Nursery

Part 2: Biological Control Methods

*Based on EDA/UCC Data from 01/01/2018 - 12/31/2022 for sales of new compact tractors 0-200 Hp in the state of Tennessee.

Green Roofs and Green Roof Research at the University of Tennessee Highlights from Field Day at UT

Biological Control in the Nursery Part 2: Biological Control Methods

The Tennessee Nursery and Landscape Association serves its members in the industry through education, promotion and representation. The statements and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the association, its staff, or its board of directors, Tennessee Greentimes, or its editors. Likewise, the appearance of advertisers, or their identification as Tennessee Nursery and Landscape Association members, does not constitute an endorsement of the products or services featured in this, past or subsequent issues of this quarterly publication. Copyright ©2024 by the Tennessee Nursery and Landscape Association. Tennessee Greentimes is published quarterly. Subscriptions are complimentary to members of the Tennessee Nursery and Landscape Association. Third-class postage is paid at Jefferson City, MO. Printed in the U.S.A. Reprints and Submissions: Tennessee Greentimes allows reprinting of material. Permission requests should be directed to the Tennessee Nursery and Landscape Association. We are not responsible for unsolicited freelance manuscripts and photographs. Contact the managing editor for contribution information. Advertising: For display and classified advertising rates and insertions, please contact Leading Edge Communications, LLC, 206 Bridge Street, Suite 200, Franklin, TN 37064, (615) 790-3718, Fax (615) 794-4524.

Jon Flanders

TNLA would like to thank the following companies for being Membership Sponsors Arboras, LLC.

GOLD Membership Sponsors

Barky Beaver Mulch & Soil Mix, Inc.

BASF

Blankenship Farms and Nursery

Botanico, Inc.

BWI of Memphis

Cam Too Camellia Nursery, Inc.

Delta Mulch and Materials, LLC

Drees Plant Wholesalers

Enviro-Scapes, LLC

Flower City Nurseries

Mid-South Nursery

NYP Corp.

Randall Walker Farms

Riverbend Nurseries, LLC

Swafford Nursery, Inc.

Swift Straw Tennessee 811

Tennessee Valley Nursery, Inc.

Turner & Sons Nursery

Warren County Nursery, Inc.

Youngblood Farms, LLC

SILVER Membership Sponsors

3F - Flanders Family Farm

Dayton Bag & Burlap Co.

Carpe Diem Farms

Cherry Springs Nursery

Kinsey Gardens, Inc.

Mid-South Nursery

Mike Brown’s Wholesale Nursery, LLC

Old Courthouse Nursery

Rusty Mangrum Nursery

Samara Farms

Scenic Hills Nursery

Star Roses and Plants

Woodbury Insurance Agency

xciting news! This year’s golf classic will be held at Fall Creek Falls on Friday, October 18th, 2024. It is a bucolic championship course on the Tennessee Golf Trail and has many upgraded amenities. Be sure to sign your team up and secure your sponsorship as the number of teams and carts are limited. Pro Tip: if you want to stay at the newly renovated Lodge make your reservations early. The next evening, Saturday, October, 19th, 2024 will be our annual awards banquet and membership meeting at the Magnolia Event Center in McMinnville, TN. Please RSVP when the invitation comes out so that we can be sure to plan the catering. More information to come on both events.

We are migrating to a new suite of tools on our website. This will make management of programs and memberships more efficient for the staff and board members, but more importantly it will improve your user experience. If you haven’t logged on recently check us out at https://www.tnla.com. We are working on our new Buyers’ Guide. TNLA has not published a Buyers’ Guide since 2011.

Save the Date! TNGRO is back at the Farm Bureau Expo Center in Lebanon, TN on October 23–24, 2025. We have entered into a three-year contract to do TNGRO at this location every Fall going forward. As always, we have some opportunities to serve on committees coming up. We would love to have your input and participation as this is a membership ran organization. Please reach out to Executive Director Danae Bouldin if you have any questions. Thank you for being a member of TNLA. We are stronger when we work together.

Jon Flanders TNLA President

Star Roses and Plants

Guy Hartsell

8 Federal Road, Suite 6

West Grove, PA 19390 (252) 229-0694

ghartsell@starrosesandplants.com www.starrosesandplants.com

Cultivate Sourcing Group

Hank Mary 5731 Lyons View Pike #206 Knoxville, TN 37919 (865) 680-9420

hank@cultivatesourcing.com https://cultivatesourcing.com

The Tennessee Greentimes is the official publication of The Tennessee Nursery & Landscape Association, Inc.

115 Lyon Street

McMinnville, Tennessee 37110 (931) 473-3951

Fax (931) 473-5883

www.tnla.com

Email: mail@tnla.com

Published By

Leading Edge Communications 206 Bridge Street, Suite 200 Franklin, Tennessee 37064 (615) 790-3718

Fax (615) 794-4524

Email: info@leadingedge communications.com

Editors Dr. Bill Klingeman Dr. Amy Fulcher

Associate Editors Dr. Karla Addesso

Dr. Becky Bowling Dr. Nick Gawel

Dr. Midhula Gireesh

Dr. Nar Ranabhat

TNLA Officers

President Jon Flanders Botanico, Inc. & 3F - Flanders Family Farm

1st Vice President

Ozzy Lopez Ozzy’s Lawncare and Hardscape Services

2nd Vice President

Sam Kinsey Kinsey Gardens

3rd Vice President

Trista Pirtle Pirtle Nursery

Secretary-Treasurer

Bryan Tate

Mid-South Nursery

Associate Director

Todd Locke BWI of Memphis

Ex-Officio

Terri Turner Turner & Sons Nursery

Executive Director Danae Bouldin

TNLA had a great turnout at our Field Day at UT Gardens! Thank you to our attendees, sponsors, and the staff at UTIA for supporting TNLA and our green industry!

and

By Dr. Becky Bowling (Follow me @TNTurfWoman, Follow us @UTTurfgrass)

Assistant Professor and Extension Specialist, University of Tennessee

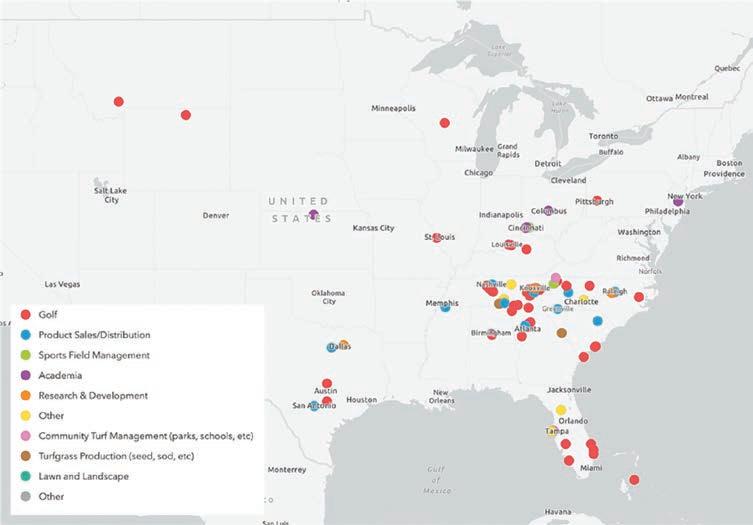

InOctober 2023, the UT Turfgrass program launched its UT Turfgrass Alumni network. A brief questionnaire has been used to create a visualizable, public-facing University of Tennessee Turfgrass Alumni map to showcase the reach of UT Turfgrass alumni across the globe and within the industry (Figure 1). Links to the live map and questionnaire are provided at the end of this article. The network allowed us to collect information about our impressive alumni, which we thought may be interesting and fun to share here with our Tennessee nursery industry.

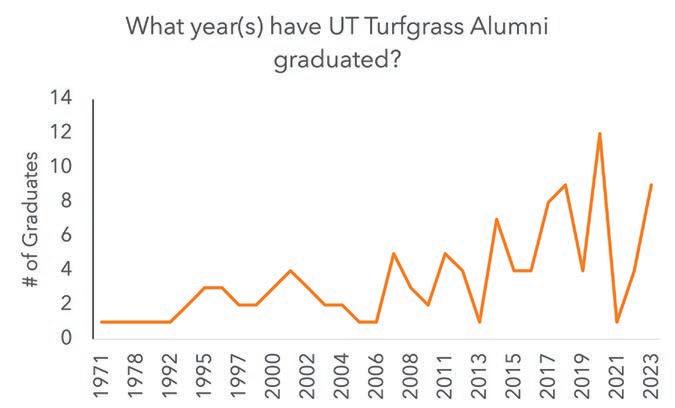

The network includes alumni who may have received multiple degrees from UT. To date, 118 alumni have joined the network, with 108 earning a bachelor’s degree, 15 earning a master’s degree, and 10 earning a PhD between 1971 and 2023. Figure 2 depicts trends in graduation numbers among alumni that have joined the network so far. Approximately 74% alumni members majored in Plant Sciences, roughly 21% majored in Ornamental Horticulture and Landscape Design, and the remaining 5% pursued other majors like Ag Business with a minor in turf.

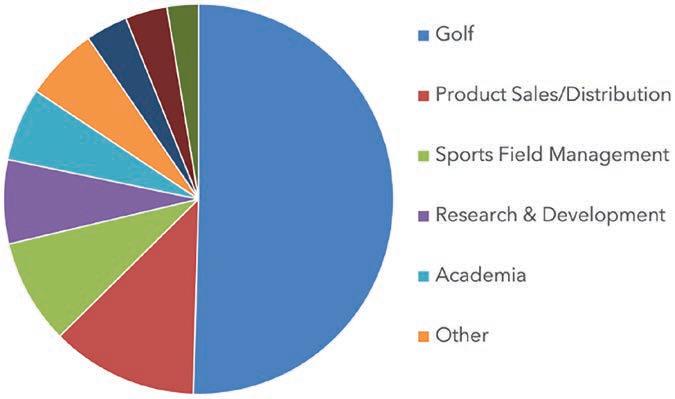

Network members were asked whether they were willing to share the sector of the industry they work in. Exactly 50% of all members work in the golf industry, while 8.5% work in sports field management, 3.4% work in community turf management (schools, parks, etc.), 2.5% work in lawn and landscape, 3.4% work in turfgrass production, 11.9% work in product sales and distribution, 6.8% work in research and development, 7.6% work in academia, and all remaining respondents work in other areas. This breakdown is depicted in Figure 3, while the geographic distribution of industry impact is shown in Figure 4.

The network will create new opportunities for alumni to see and connect with each other, while also providing a reliable mechanism for our UT Turfgrass program to engage alumni in news, events, and other opportunities to stay involved in our program in the future. We look forward to staying connected and keeping track of alumni as they advance in their careers and leave their mark on the global turfgrass industry.

University of Tennessee Turfgrass alumni are also encouraged to check out Vols in Turf, the University of Tennessee Turfgrass Science Program Alumni Foundation. Founded as a 501(c)(3) in 2021 by motivated alumni seeking to connect with and support former, current, and future program graduates. Visit their website at https://volsinturf.square.site or follow them on X @TurfVols.

UT Turfgrass Alumni Network Map: https://myutk.maps.arcgis.com/apps/ instant/basic/index.html?appid=78909f2f92 4440979051603c89f3718a

Join the network here: https://arcg.is/0WPjCW

Anna Duncan 1, Dr. Becky Bowling 2, and Dr. Jim Brosnan 3

1Digital Education and Training Program Coordinator; 2Assistant Professor and Extension Specialist, 3Professor Dept. of Plant Sciences, University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture

In2023, the UT Turfgrass Science program and UT Extension launched the Certified Lawn Care Professional (CLCP) program for anyone looking to bolster or begin their career in the turfgrass industry. The program, taught by University of Tennessee faculty and staff, provides education and skills needed to effectively establish and maintain turfgrasses using a format that is completely online and self-paced.

In its first year, 107 participants enrolled in the CLCP course and awarded it an average rating of 4.8 out of 5 stars. Participants cite increased customer satisfaction and increased credibility of service as top benefits of earning this certification. When asked to provide feedback on the course, one participant said, “I thought this was a great introduction of the basics of turf for a beginner coming in new to this field or even for field veterans. Excellent work!” Others provided similar comments including: “Good [information], presented in a digestible form.” and “Great course! Easy to understand. Y’all did an awesome job with videos and materials.”

This course is well-suited for anyone who currently manages turfgrass or wants to start a career in the industry. Introductory information is provided on several topics:

• Turfgrass Identification

• Turfgrass Selection

• Soil Fertility

• Water Management

• Planting and Establishment

• Turfgrass Weeds

• Turfgrass Diseases

• Turfgrass Insect Pests

• Integrated Pest Management

• Maintenance and Operation of Turfgrass Equipment

Upon finishing the course, participants are awarded a certificate of completion from the University of Tennessee Extension Certified Lawn Care Professional Program. This certificate is valid for two years and can be renewed thereafter by completing additional education that builds upon the topics covered in the initial course and provides further accreditation for participants.

The fee for this course is $250. Participants may enroll in the course at any time.

For more information and to register, visit tiny.utk.edu/CLCP, or contact your local Extension Agent.

STAINLESS COVERCROP SEEDERS

500 lb. capacity

Adjustable from 36" – 72" wide

Ground drive for consistent application

Linkage for positive height adjustment

Four easy change sprockets for feed rate adjustment

Stainless steel hoppers and metering system Approximate feed rates: 16-16-16

CULTIVATORS

Side shields float

Pneumatic gauge wheels

Works great for planting covercrop with seeder

or

INCREASE PROFITS WITH THE SPEED OF A DISC VERSUS A TILLER. SIZES FROM 34" – 40"

Greasable agriculture disc bearings

Shovel eliminates center line

12, 16" notched blades

Four adjustable cutting angles

float in rear 2 1/2 square tube frame

Adjustable side shields contain soil

Custom sizes up to 60"

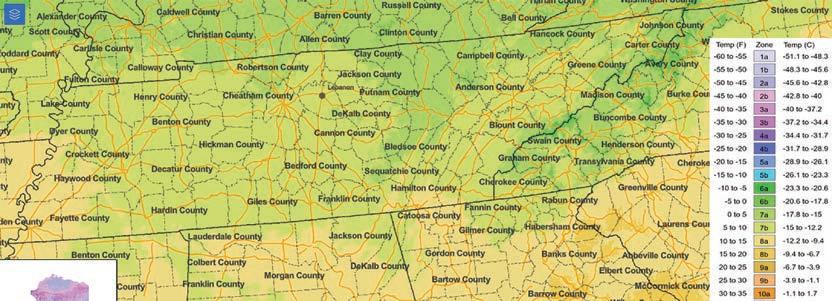

Not updated since its last revision in 2012, last November 15, the USDA ARS and partner PRISM Climate Group partners at Oregon State University released the much-anticipated 2023 update to the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map. The changes reflect a shift to warmer average annual extreme minimum temperatures during the most recent 30-year past period. As in previous versions, the 26 recognized Plant Hardiness Zonal divisions are presented with set temperature ranges based upon F-degree (F) half-zones, which can be

searched by Zip Code. When planning for plant selection, growers are encouraged to remember that microclimate (small-scale) effects occur that can affect success of plants selected to be hardy within any given zonal range distribution.

The new map designations for the US, plus Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico, can be found at https://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/, along with Tips For Growers and guidance about using the online map resources and its “on demand” layers.

Hello and thank you for giving me this chance to introduce myself. My name is Kaitlin Barrios and I started at TSU’s Otis Floyd Nursery Research Center in McMinnville on June 1st. I am the Nursery Extension Specialist with Tennessee State University. I will be working with ornamental growers in the middle TN region through on-site visits, coordinating and providing educational sessions, and helping write and disseminate fact sheets. I look forward to meeting growers and learning about their production systems.

I am originally from Baton Rouge, Louisiana and studied landscape architecture at Louisiana State University (LSU) and graduated with a BLA in 2007. Next, I helped teach English in rural schools in Spain. Since I love seeing the world, learning about other cultures, and practicing my Spanish, it was a great experience. After that, I studied for a Masters degree at LSU in the School of Plant, Environmental, and Soil Sciences. My research focused on a coastal grass, sea oats, that builds sand dunes and combats erosion from powerful winds and flooding. At that time, I trialed fungicides to improve germination and seedling survival of sea oats for coastal restoration and took some plant breeding courses that I found fascinating.

In 2013, I began work as a Research Associate at LSU assisting with Extension work and breeding of energycane, which is sugarcane bred for reduced sucrose and enhanced traits for using as an energy source. I liked the lab and field work and found that I really enjoyed my Extension efforts with elementary students and the public about agriculture. I also appreciated that growers were able to use our research results to improve their operation and/or make their business more efficient. In 2015, I joined the research team as a PhD student working at the University of Georgia (UGA) in the Department of Horticulture and in Field Day events and research at the UGA Trial Gardens. My doctoral research focused on breeding and research of ornamental plants, primarily hardy hibiscus or swamp mallow (Hibiscus moscheutos), which has remarkable phenotypic diversity, and can be developed for ornamental characteristics for flower color(s), size, and angle; leaf shape, color and size; leaf hairiness or pubescence; plant height and width; leaf internode spacing/compactness; flowering period; etc. We also were selecting plants for disease and pest resistance to Japanese beetle, whiteflies, and hibiscus sawfly, which when left unchecked, can rapidly defoliate plants. Because we observed a lot less feeding damage on hairy leaves compared to smooth leaves, we included those lines in our hand-pollinated crosses. During that work, I learned propagation, weed management, irrigation installation, and field planting.

While at UGA I briefly worked at Star® Roses and Plants (SRP), that had partially supported some of my research, and then joined the SRP team full time during the pandemic in 2020. At SRP, I propagated

plants in their advanced selection stage through vegetative ex vitro (greenhouse) and in vitro (sterile culture) methods. That way, liners would be available to distribute if or when selections became releases. I transitioned into ornamental breeding and research of woody plants, including hardy hibiscus to potentially add to the Head Over Heels® series. I loved the work yet missed opportunities to share research results with a large audience and the fulfillment of helping others through my work. Since leaving SRP, I have worked as a Horticulturist at a public garden and helped teach a woody native plant identification course at the University of Delaware. I am thrilled to have landed this Nursery Extension Specialist position with TSU and I look forward to serving TN nursery growers. Please reach out to me at kbarrios@tnstate.edu if you have any questions concerning nursery plants.

By Michael Ross, SITES AP, ASLA Assistant Professor, Plant Sciences Department + School of Landscape Architecture, University of Tennessee

and James D. Zimmerman,

MLA Graduate Student, School of Landscape Architecture, University of Tennessee

Green roofs have been used for centuries to mitigate stormwater, insulate buildings, preserve architecture, and increase sustainability in the built environment. (Dunnett, 2008). Throughout Scandinavia and in the US Great Plains, sod, native grasses and forbs, and earthen roofs have been a traditional building material.

As a design element and constructional component, green roofs are well understood. Loading rates, water retention, architectural modification, and individual components can often be adjusted and optimized to meet specific outcomes. This flexibility allows variability across green roof systems that will be unique to each project. Green roofs help insulate buildings, reduce albedo (light and radiated energy reflectance), mitigate urban heat island effect, capture stormwater, and provide biological resource habitat.

The design-build firm Living Roofs, Inc. in Asheville, NC specializes in green roofs, and their founding partner and design principal Kathryn Ancaya, PLA, describes these installations as:

“…more than a decoration, green roofs are a powerful and effective tool for building regional resilience. Green roofs address significant climate challenges impacting our region, specifically: urban heat, biodiversity loss, and the damaging effects of stormwater runoff. A green roof also presents an opportunity to create multi-species habitat, restore native plant communities, and provide stopover sites for migratory species. Whether we are working on a brownfield site on the edges of Columbia, SC, a multi-story apartment building in downtown Asheville, or a tiny kiosk in a neighborhood park, we look to native plants and ecology for inspiration. Rooftops are an unlikely space for plants to grow and present a unique set of environmental conditions” (K. Ancaya, personal communication)

There are three main types of green roof systems that allow for opportunities across a variety of conditions: extensive, semi-intensive, and intensive green roofs. For years now, extensive green roofs have done a fair job of meeting the basic green infrastructural needs of the built environment. They are reasonably light, mitigate stormwater, add thermal insulation to a building, and are adaptable enough to have decent survival rates. Sedums are typically the species of choice for extensive green roofs and are light enough that they are often the best option to retrofit an existing roof. Companies have even gotten to the point that they can pre-grow sedum trays that are then placed in sequence on the roof for an efficient and relatively inexpensive green roof. Extensive green roofs are relatively low maintenance once established.

Semi-intensive green roofs are similar to extensive green roofs as they are still lightweight and require relatively little specialized structural support. While this type of green roof still mitigates stormwater and adds thermal insulation, they have an additional ecological function. Instead of using sedums as the plant material, semi-intensive green roofs begin to incorporate low growing, lightweight grasses, forbs, and perennials. Using a diversity of these plant types allows for higher ecological function and ecosystem services by increasing genetic and structural diversity, organismal interactions, and aesthetic performance. The design-build firm Living Roofs Inc. project Camp Mending Heart (Figure 1) is a good example of a diverse semi-intensive green roof.

Intensive green roofs require more structural support, higher initial investment, and more intensive maintenance. However, because they are intensive, these green roofs allow for larger and more complex plantings and typically provide an amenity space. They can even be experienced or programmed to serve as a garden or park. Intensive green roofs are occupiable for human use. The overall soil depth of intensive green roofs can range from 8" – 30", which requires greater structural support. Intensive green roofs tend to be much more expensive to design and install than extensive or semi-intensive roofs, yet tend to provide greater long-term benefits that include energy cost savings, extended roof lifespan, and increased property value.

Some landscape architecture firms, such as Living Roofs Inc., Omni Ecosystems, and Andropogon Associates have embraced green roofs as all or part of their work. Omni Ecosystems’ business model includes design and development of green roofs, such as Omni Ecosystems Headquarters (Figures 2, 3), and green roof products, such as Omni Infinity Material. The Omni Ecosystem Headquarters green roof includes a diversity of native plantings and an ADA accessible rooftop deck. Omni describes their Infinity Media as a “horticulture growing medium that is used as rooting substrate supporting plant growth in on-structure applications” (Omni Ecosystems, 2024).

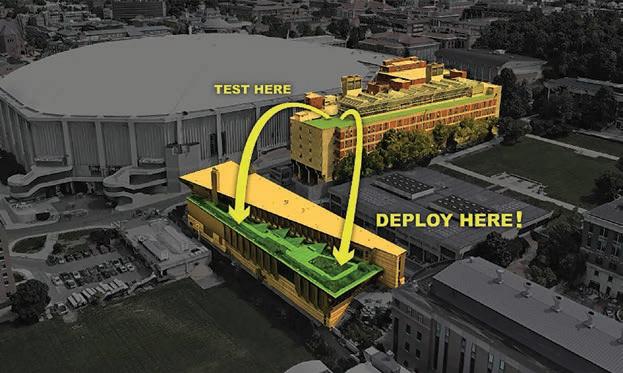

Andropogon Associates include green roofs in several of their designed projects, such as U.S. Coast Guard Headquarters, INCYTE Corporation, and SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry (Figures 4, 5, 6). During the construction of the SUNY green roof, Andropogon’s design team experimented with test plots on an adjacent building’s rooftop (Figures 7, 8). During this experiment, they tested several variables, including soil depth and planting mixture, that helped to determine the best strategy for vegetated areas of the planned green roof. These firms have been developing and researching green roofs in the professional realm for several years and have been the precedent for current green roof research occurring at the University of Tennessee.

Figures 2 and 3.

Omni Ecosystems Headquarters Green Roof. Images courtesy of Omni Ecosystems and Scott Shigley.

Figures 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8.

SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry. Design and research done by Andropogon Associates. Image courtesy of Andropogon Associates

As part of the Living Systems Design Group, established within the Ross Lab at the University of Tennessee, green infrastructural applications are deployed and evaluated in terms of biodiversity, species richness, and ecological performance. At present, these applications serve as core elements of experiential learning and sources of scholarly outputs. Ecological systems that perform multiple services in designed and built environments that include green roofs provide interesting to study the impacts of climate change, species competition, succession, colonization, and occupation.

The Green Roof Experimental Lab at the University of Tennessee seeks to explore the ecological function, hybrid ecology, and ecosystem service production of green roofs (Figure 9). This project was made possible through collaboration with the Department of Plant Sciences, School of Landscape Architecture, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, and the UT Gardens. Experimental research is conducted on biodiversity and spontaneous plant colonization, mycorrhizal interactions, organic decomposition rates, organismal interactions, and aesthetic performance of roof systems that preference native plant communities. Green roof media was sourced from Omni Ecosystems. Units were designed and constructed by students in the College of Architecture and Design and Department of Plant Sciences Sustainable Landscape Design concentration (Figure 10). Students were trained in Omni Ecosystem’s methodologies and green roof media establishment protocols. Units were designed to be mobile in case of emergency by skid-steer. The units aim to provide immersive teaching opportunities, a method for reducing ambient temperatures in built systems, a means of reducing stormwater runoff, create novel native habitats, improve air quality, reduce ambient noise, and to provide research opportunities (Figure 11). Green roof research is also in progress on the roof of the Sustainable Landscape Design concentration’s storage unit, where a native pocket prairie is being established. In 2009, a sedum green roof was installed.

Over the last couple of years, a decision was made to retrofit the storage shed roof with an ecologically diverse, functional pocket prairie. Old media was removed, and Omni Ecosystems media was incorporated to develop a hybrid system. Native species were interplanted into the existing sedum, creating a hybrid prairie and sedum system with approximately 17 different species (Figures 12, 13).

In 2024, the new Agriculture and Natural Resources (ANR) building on the University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture’s campus will be completed. An intensive green roof is proposed to be built where additional research and design opportunities will continue to develop. As proposed, this green roof installation will support several different and ongoing program initiatives, including monitoring the performance of green roofs across time. The design proposal will contain an outdoor classroom, a multi-use plaza, green roof trial beds, and a weather and green roof monitoring station.

Green Roof research initiatives at the University of Tennessee stand at the forefront of advancing sustainable solutions for the built environment. Through collaborative efforts across disciplines and partnerships, with industry leaders like Omni Ecosystems, students and faculty are not only exploring the ecological functions and ecosystem services of green roofs, but also actively contributing to their evolution and innovation. The future of green roof research at the University of Tennessee will further enhance our understanding and application of green infrastructure for a more sustainable and resilient future.

Ancaya, K. (2024, March 7). Kathryn Ancaya quote.

Andoropogon Associates. (n.d.). SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry. Andropogon. https://www.andropogon.com/project/ suny-college-of-environmentalscience-forestry/

Andropogon Associates. (n.d.). Incyte Corporation. Andropogon. https://www.andropogon.com/project/ incyte-corporation/

Andropogon Associates. (n.d.-b). U.S. Coast Guard Headquarters. Andropogon. https://www.andropogon.com/project/ u-s-coast-guard-headquarters/ Archtoolbox. (2021, September 19). Green roof systems: Intensive, semi-intensive, and extensive. https://www.archtoolbox.com/ green-roof-systems

Environmental Protection Agency. (2023). Using Green Roofs to Reduce Heat Islands. EPA. https://www.epa.gov/heatislands/ using-green-roofs-reduce-heatislands#:~:text=Green%20 roofs%20provide%20shade%2C%20 remove,effect%2C%20particularly%20 during%20the%20day

Green Roof Technology. (2021, October 16). Intensive green roof. https://greenrooftechnology. com/green-roof-finder/intensivegreen-roof/

Living Roofs, Inc. (n.d.). Camp mending heart: Single family :: Living roofs inc.. Camp Mending Heart | Single Family :: Living Roofs Inc. https://www.livingroofsinc.com/ projects/camp-mending-heart

Omni Ecosystems. (n.d.). Omni Ecosystems Headquarters. https://www.omniecosystems. com/portfolio/omni-ecosystemsheadquarters

Omni Ecosystems. (n.d.-b). Omni Rewild. https://www.omniecosystems.com/ omni-rewild

SLD Living Systems Design [Ross] Lab https://sldlivingsystemslab.utk.edu

“The more than one company agency”

“Since 1901”

114 S. COURT SQUARE • P.O. BOX 669 M c MINNVILLE, TN 37111 (931) 473-2200 • CELL (931) 212-9856

E-Mail: hooverins@blomand.net • www.hooverins.com

By Alfred Daniel J, Kripa Dhakal, and Karla M Addesso

Tennessee State University, Otis L. Floyd Nursery Research Center, 472 Cadillac Lane, McMinnville, Tennessee, 37110, USA.

InPart 2 of this 3-part series, we discuss three uses of predators and parasitoids in common biological control programs. While all of them utilize natural enemies to manage pest populations, the amount of time, effort and financial resources needed to employ each will differ. In Part 1, we reviewed the different categories of biological control agents that include predators, parasitoids, and entomopathogens. In Part 3 of this series, we will more thoroughly discuss microbial control products.

Using a hand-help blower to apply the predatory mite, Amblyseius swirskii, to maple tree liners to manage broad mites.

There are three common approaches to biological control programs. The first approach involves the conservation of existing natural enemies (called conservation biological control) and seeks to sustain beneficial insects that already are present in the environment by making production decisions that help to boost natural pest control. The second approach includes the purchase and release of mass reared beneficial insects into a greenhouse or nursery to provide control of specific targeted pests (called augmentative biological control). Depending on the level of active pest pressure, these beneficial insect releases may be made once or multiple times across a growing season, similar to actions taken to apply chemical pesticides. Augmentative biological control is applied in areas where beneficials are excluded, like a greenhouse, or where natural enemy populations are too low to control the target pest effectively.

3) The final method of biological control seeks to introduce or import natural enemies from their native range and establish a permanent population in a new area (a practice also called classical biological control). This method often is used by Federal regulatory bodies when a damaging invasive insect spreads to a new region within the US. Most often, these damaging invasive species are imported from their non-native source without their natural enemies that help keep their populations in check within their original range. The goal of classical biological control is to reunite invasive insects with their natural enemies form which they have previously escaped with the objective of re-establishing a natural balance to the invasive pest population within the non-native region. At present, classical biological control programs take many years of regulatory research and careful consideration of the potential risks and benefits prior to any approval for release of natural enemy organisms. In contrast to importation for classical biological control, conservation and augmentative biological control are the two methods that greenhouse and nursery growers can utilize in their production systems.

Two main methods can help promote existing populations of beneficial control organisms are to provide or supplement suitable habitat and to reduce the use of broad-spectrum insecticides. Many beneficial insects, particularly parasitoids, require nectar to increase their survival. Strips of wildflowers left growing or seeded into the borders of nursery blocks can provide nectar, pollen, and shelter to beneficial insects. In areas where goldenrod and Queen Anne’s lace are common, avoid mowing or spraying these areas with pesticide. These plants will attract different types of natural enemies and provide food and shelter for them. Planting/ seeding flowering cover crops such as clovers into row middles can also provide food and habitat for beneficial insects. When pest problems do arise, if possible, select a short-duration or systemic pesticide that specifically targets your pest, rather than spraying a broad-spectrum product. Apply pesticides later in the day to avoid contact with beneficial arthropods. These practices can conserve resident natural enemies and are less expensive and time consuming than augmentative biological control.

Augmentative releases of biocontrol agents can be inoculative, wherein relatively few natural enemies are released with the hope that

these insects reproduce and the offspring continue to provide control over time, or inundative, where large numbers of natural enemies are released and to control a specific problem, but long-term control is not expected. Control duration is also affected by use of winged adult natural enemies (e.g., lady beetles or lacewings) that may readily disperse from the point of release. Augmentative biological control has been used successfully for many years in greenhouse systems to control thrips, whiteflies, and mites. Successful programs are easier to develop in closed environments because beneficial organisms cannot disperse as easily out of the greenhouses, whereas in container and field production systems, flying insects can leave if pests are scarce. Augmentative biological control in container production has been most successful with predatory mites and juvenile life stages of predators, which can disperse within the container yard where the canopies of plants touch, yet cannot fly away when pest pressure declines. Biological control programs can be cost-competitive and as effective as chemical control when well-designed. Some major benefits to using biological control agents are labor savings compared to traditional chemical sprays and zero REI. Most beneficial supply companies (https://anbp.org/members) have consultants who work with a nursery to implement control programs for their specific needs. Programs can be trialed in one greenhouse or container yard and scaled-up after optimization.

By Dr. Alicia Rihn University of Tennessee, Assistant Professor, Agricultural & Resource Economics Department

U.S. economy has several indicators that directly impact the Green Industry. Today, I will focus on the overall health of the economy (GDP, LEI), housing market, and consumer confidence and spending. Each of these indicators give insights into how people may be approaching landscaping and other Green Industry projects in the upcoming months and year.

Generally, the U.S. economy is positioned better than it was in the past couple of months. At the end of July, the GDP (which reflects the overall economy health) was at 2.8% and is projected to remain around 2% in the upcoming months (Trading Economics, 2024) (Figure 1). Relatedly, the Leading Economic Index (LEI; indicates economy health and recession signals) has increased indicating that the risk of an economic recession has decreased. As of August, the U.S. inflation rate has also stabilized at 2.9% ( Figure 2 ) and the unemployment rate has remained relatively consistent at 4.3% (Trading Economics, 2024).

The U.S. housing market tends to lag slightly behind the general economy due to contracts being in place and consumers waiting to see what the economy does prior to making big decisions. As a result, we are seeing a reduction in the housing market which is a ripple effect from inflation concerns and increased mortgage rates. Currently, the U.S. housing starts are exhibiting a slight downward trend but at a slowing pace (Figure 3). Moving forward, there is potential for demand for housing to gain traction as mortgage rates stabilize (Figure 4). Additionally, housing starts will likely pick up again as fears of a potential recession and inflation decrease. From the consumer perspective, consumer confidence and spending are trending upward (Figure 5).

Together, the current economic outlook is relatively positive. A key metric to pay attention to is the housing starts given that this indicator directly impacts landscaping projects and ornamental plant sales. Despite the current downward trend, there is still a shortage of housing inventory (Forbes, 2024), meaning that housing demand is still not being adequately met and new housing starts will likely pick up again soon.

jon.flanders@botanicohq.com