Chris Sykes

Chris Sykes

weather roller coaster ride in the transition zone is like nowhere else in the world. The entire region is still recovering from the extreme low temps experienced during the holidays with widespread winter injury. Grow-in efforts have been further slowed by continued cool temps well into the spring with frosts as late as the end of April. Sod farms are not exempt from these setbacks. You combine that with the supply chain issues and it makes for an even slower recovery process due to the lack of available plant material.

While I have recently relocated to South Florida, Mother-Nature is still large and in charge. Winter injury isn’t a concern, but the availability of water has been this spring. While nearby areas like Ft. Lauderdale have experienced floods of historic nature, we have been in a severe drought at PGA Golf Club in Port St. Lucie. You mix in the lack of available water, warmer than normal temps with low humidity, and the challenge to keep grass alive is real. Through the middle of April, we had received less than 2” of rain, so the courses were for sure playing firm and fast. I am enjoying the weather to this point, but I am again reminded as I write this article of who is in charge as next week, June 1st is the first day of the 2023 hurricane season.

There is never a dull moment in the world of turfgrass and mother-nature will always remind us of who is really in charge. We are just along for the rollercoaster ride and respond accordingly.

Godspeed on a great growing season for all!

Always a Tennessean,

Chris Sykes

TTA President

info@ttaonline.org www.ttaonline.org

PUBLISHED BY Leading

(615) 790-3718

info@leadingedgecommunications.com

EDITOR

TTA

TTA

•

•

•

•

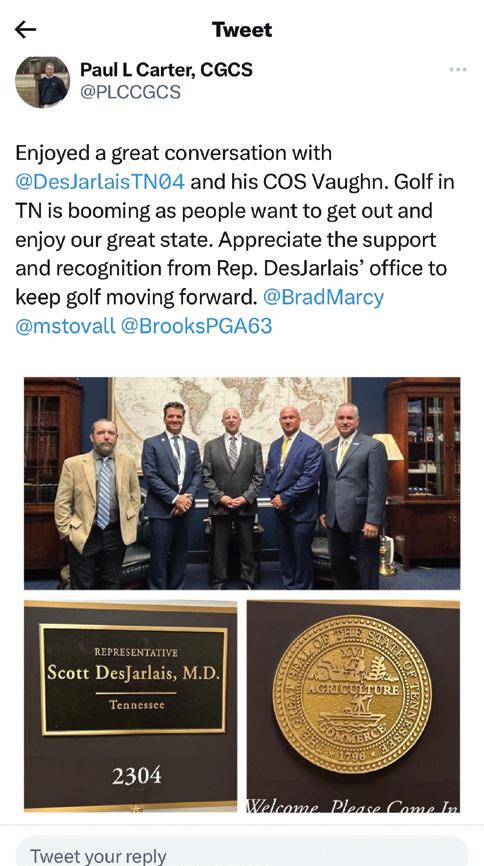

ational Golf Day is a time for the golf industry members to come together to work on service projects and participate in meetings with members of Congress. This year I had the privilege of representing the Tennessee Chapter at this event. There were 39 states and 162 unique House Districts represented with nearly 250 total attendees, a record for in-person National Golf Day.

Participants completed service beautification projects on The National Mall. We also attended meetings at Capitol Hill to advocate for the golf industry on legislative and regulatory issues. We asked for federal dollars for turfgrass research to develop more environmentally friendly grass types. Also, we would like to expand access to the H-2B visa program to meet the labor demands that we are currently facing. In addition, we were supporting the PHIT Act and modernizing the U.S. tax code to eliminate old, restrictive IRS language prohibiting the golf industry from accessing financial investments.

Funds raised through the Tennessee Rounds 4 Research donations are used each year to send a minimum of two Tennessee chapter members to this event. This year myself and Brad Marcy were awarded those funds to attend. I would like to thank our chapter for the dedication and donated rounds that made this possible. It was a privilege and honor to represent the State of Tennessee along with Brad Marcy, Paul Carter, and Brooks West. If you would like to represent our chapter at the 2024 National Golf Day, please contact the association at info@tgcsa.net

Mark Stovall

Territory Manager

Harrell’s

TN GCSA Board Member

JULY 24, 2023

ETGCSA July Meeting

WindRiver Golf CLub Lenoir City, TN

AUGUST 10, 2023

FedEx St. Jude Championship TPC Southwind Memphis, TN

AUGUST 14, 2023

ETGCSA August Meeting

Moccasin Bend Golf Course Chattanooga, TN

SEPTEMBER 11, 2023

ETGCSA September Meeting

The Patch Oak Ridge, TN

SEPTEMBER 18, 2023

MTGCSA September Meeting

The Course at Sewanee Sewanee, TN

OCTOBER 23, 2023

33rd Annual East Tennessee Scholarship and Research Golf Tournament

Tennessee National Golf Club Loudon, TN

NOVEMBER 1, 2023

2023 MTGCSA Scholarship & Research Golf Tournament

Gaylord Springs Golf Links Nashville, TN

JANUARY 8 – 10, 2024

58th Annual TTA Conference & Trade Show

Embassy Suites Murfreesboro, TN

For event

and updates throughout the year, visit www.ttaonline.org www.tgcsa.net

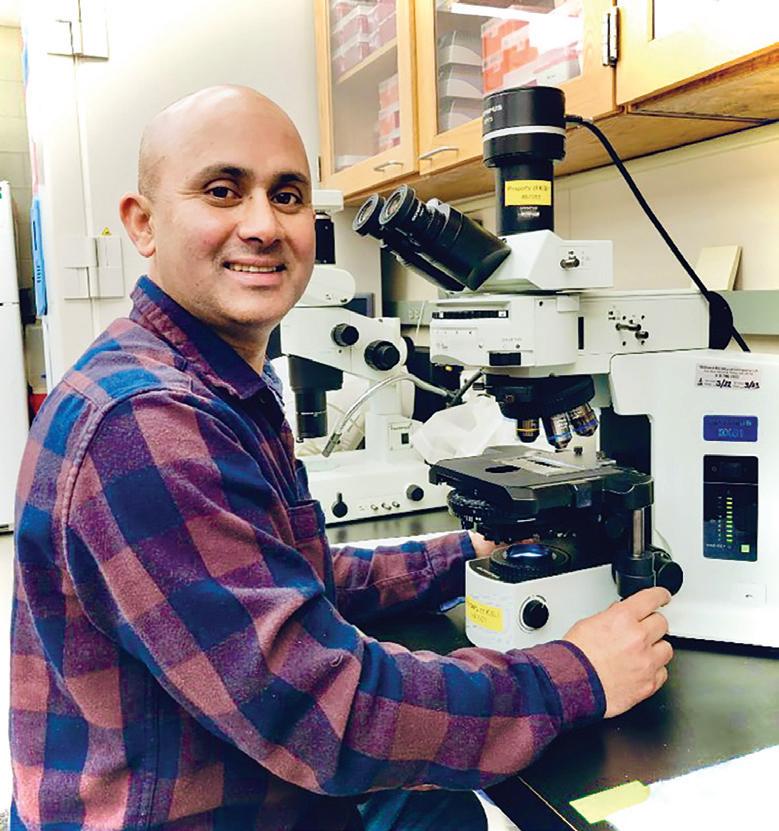

Hello Tennessee! My name is Midhula Gireesh and I have recently been hired as a faculty member in the Entomology and Plant Pathology Department at The University of Tennessee. As an Extension Entomologist, I will be involved in diagnosing and managing arthropod pests of ornamental plants, nursery plants, and turfgrass. I am looking forward to meeting as many of you as possible during my initial months in this position. My official start date is June 1, 2023, and will be based at the Soil, Plant, and Pest Center in Nashville.

Until we get to meet in person, here is a little of my background. I grew up in Kerala, a southwestern coastal state of India, which is known as “God’s Own Country” for its natural beauty and vibrant culture. During high school days, the concept of “hybridization” taught in a biology class grabbed my attention. Moreover, I was curious to learn about plants. This compelled me to take a double major in Botany and Biotechnology for pursuing my BS. For my post-graduate studies, I chose MS in Genomic Science, which deals with the advancements in genomics and genetics. After completing Bachelors and Masters from India, I moved to the US to pursue my doctoral degree in Entomology at the University of Georgia in 2018.

During my doctoral program, I was exposed to the world of insects and agriculture and took a 180° turn in my career goals. My doctoral research involved developing Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strategies for hunting billbugs in the turfgrass production (sod) farms of central Georgia. My initial research goals were to record the major billbug species, their seasonal occurrence, abundance, and movement activity in the turfgrass. Later, my research focused on determining the influence of abiotic factors on the movement of hunting billbugs under field, semi-field, lab conditions and the spatial distribution of hunting billbugs. Ultimately, the aim was to improve the sampling plan and develop an IPM strategy for hunting billbug problems in sod farms. Additionally, I have conducted a survey to determine the major turfgrass pests and current management practices adopted by golf course superintendents and sod producers.

Soon after my graduation, I received the opportunity to work as postdoctoral research associate at the Gulf Coast Research and Education Center, University of Florida. In September 2021, I joined the Small Fruit Entomology lab where my research focused on developing integrated pest management strategies for thrips pests of strawberry in Florida. My applied research involved manipulation of available management strategies including cultural control, biological control,

and chemical control to suppress chilli thrips ( Scirtothrips dorsalis Hood) and twospotted spider mites ( Tetranychus urticae Koch) populations in conventional and organic strawberry fields. Besides research responsibilities, I have utilized opportunities to foster my skills in extension through face-to-face interaction with growers, field visits, extension meetings, presentation, and publications. I have been an active member of the Entomological Society of America since 2019. Music and tea are my favorite stressbusters. In my free time, I love to sing while having the perfect cup of tea. Also, I catch up with my family and friends back home, and I enjoy cooking.

When I arrive in Nashville in June, I am looking forward to meeting with Green Industry professionals to identify your specific IPM needs. Once specific IPM needs are identified, I will be integrating my academic knowledge and research expertise to study various aspects of IPM. I truly believe in face-to-face interactions with the growers and will arrange as many farm visits as possible and work closely with the county Extension agents. My broader interests are to conduct problem-solving research that eventually develops into an effective, sustainable IPM program while benefiting Tennessee’s clientele. Through collaboration with turf, ornamental and nursery specialists and industrial partners, I will make sure that all clientele have access to and benefit from my research and extension program.

From my experience in UF IFAS, and before that in Georgia, I believe that identifying specific needs from the grower is critical in developing a successful program. Through my doctoral and postdoctoral programs, I have had the opportunity to collaborate with entomologists, horticulturists, sod producers, golf course superintendents, strawberry growers, and industries. I believe these experiences will be valuable in developing insect management programs, and I hope to utilize my skills and expertise as an extension entomologist serving the needs of the nursery, ornamentals and turfgrass industries in Tennessee.

Hello, Tennessee! I am excited to introduce myself as a newly appointed faculty member of the Entomology and Plant Pathology Department at The University of Tennessee. My name is Nar Ranabhat, and I will be serving as an Extension Plant Pathologist specializing in disease management of landscape plants, nursery plants and turf. I begin at UT on July 1 and I will be based at the UT Soil, Plant, and Pest Center in Nashville. I am eager to meet with all of you during my initial months and to learn about your businesses, production systems, and disease problems. I look forward to working with you in the upcoming growing season.

Prior to the official start date, I would like to share a little bit about of my academic background with readers of “Tennessee Greentimes” and “Tennessee Turfgrass” magazines. My passion for plant pathology was ignited during a school trip to the breathtaking Rhododendron Forest in the mountains of my hometown, Pokhara, Nepal. While on this trip, my high school teacher spoke to us about the importance of protecting these stunning flowers from pests and pathogens.

Before coming to the USA, I studied the many benefits that insects provide. As an undergraduate student, I conducted a survey of pests and predators of honeybees. After graduating, I taught for a few years and then moved to the University of Hohenheim in Stuttgart, Germany where I worked on a research project exploring the suitability of pollen as an alternative food for predatory mites, which are biocontrol agents of small arthropods such as spider mites and thrips, in high-value ornamental crop systems.

I began my career in the field of plant pathology at Montana State University (MSU), where I earned my master’s degree. My research projects focused on utilizing integrated management practices to manage viral and fungal pathogens, such as Rhizoctonia, Fusarium, Pythium, and Sclerotinia, which also cause major diseases in turf. During my time at MSU, I conducted on-farm studies with local growers, which provided opportunities to interact with them and share our research findings during field days.

Later, I pursued my doctoral degree at Kansas State University (KSU), where I delved into using advanced pathogen identification tools to identify wheat viral pathogens. These viruses have a complex disease cycle, can live in grassy alternative hosts, and are transmitted by mites, making viruses difficult to manage. Accurate identification helps developing disease resistant varieties. I collaborated with multi-state breeders and private companies to develop disease-resistant wheat varieties that would yield better under Kansas growing conditions. During my post-doctoral research at KSU, my research has been focused on the development of advanced tools to accurately identify bacterial pathogens both in field conditions and in the lab. These advanced diagnostic techniques can be used to identify diseases of great importance to the Tennessee Green Industry.

When I arrive in Tennessee, I am looking forward to learning about the diseases that challenge your production systems. During my initial months, I will closely work with growers and county extension agents and plan to conduct a needs assessment to prioritize extension and research program efforts. I will initiate collaborative research of the major diseases problems and share research results with stakeholders to provide them with options.

I am excited about the opportunities to work with nursery growers and landscape industries on plant disease management, and I look forward to knowing you and your high-risk pathogen(s). Together we will find solutions that fit with your production system. Stay tuned for more updates, and I cannot wait to meet you all!

TENNESSEE TURFGRASS ASSOCIATION @TNTURFASSOC

AND FIND OTHER GREAT RESOURCES LIKE THE ACCOUNTS SHOWN HERE.

How long have you been working in the groundskeeping / turfgrass industry?

Probably around 16, I’m starting to lose track. Nine years in the MLS. I had five years at Dallas, and now I’m on my fourth year with Nashville Soccer Club. Before that I was in baseball, with the Texas Rangers for a year. I worked four years at Haymarket Park at the University of Nebraska, their baseball field. Then three or four years at Hastings Public Schools, taking care of their sports fields. That’s how I got my start.

How did you decide on a career in turfgrass management?

I started off my first time working through college for the Hastings Public Schools, taking care of athletic fields. My first round of college I got two associate degrees; one in Architectural Design, one in Construction Management. I ended up taking a three-year break where I was architectural coordinator for a company called HTR. Their primary design was hospital/healthcare. I did work on a project that pushed me back into college. It was TD Ameritrade Park in Omaha, the College World Series new stadium, which I was the project architectural coordinator on.

Working on that project, seeing the field design and the build, sent me back to the University of Nebraska, where originally I was going to get my Bachelor’s degree in construction management. At that point I was just tired of being in my office. I was in a cubicle Monday through Friday besides site visits. When I left college and left that job at Hastings Schools, it was by far my favorite job I ever had, working outside, working with grass. At that time though, I didn’t know how to get into the profession. I had no idea there were turfgrass science degrees out there.

When I went back to Nebraska, my first semester I was enrolled in construction management. One day I was just messing around online looking at what all they offer, and I came across their sports turf science program. I set up a meeting with the advisor for that and talked to her about 30 minutes. I think the last question I asked her was, ‘What jobs do I get after graduating with the degree?’ and she listed off some of her recent graduates working in baseball stadiums or golf, and that kind of sold me.

If there was an outcome where I was able to work at a stadium full time, every day, that was something that I wanted to do. I switched majors that week from construction management to sports turf science. That’s when I got into baseball, Haymarket Park. I worked there as an intern, then worked my way to a seasonal assistant, second assistant, then graduated and moved to Dallas.

Did the architectural design and construction management background prepare you for future jobs and this career?

Yes, especially for the Nashville SC job where I was part of the buildout of the stadium. We just recently opened our training facility. So when I got here, Currey Ingram was already built, which is our Academy facility. But when I was here and started getting brought in on those construction meetings, they’d put blueprints in front of me and start explaining, ‘this is keys’ and stuff like that, I didn’t have to read all that. That and construction processes, it definitely prepared me for this job and building this stadium and field. Then moving on to Antioch where our first team training facility is, it prepared me for the whole design and build process, what to expect, the steps through design/development, construction documents, then buildout.

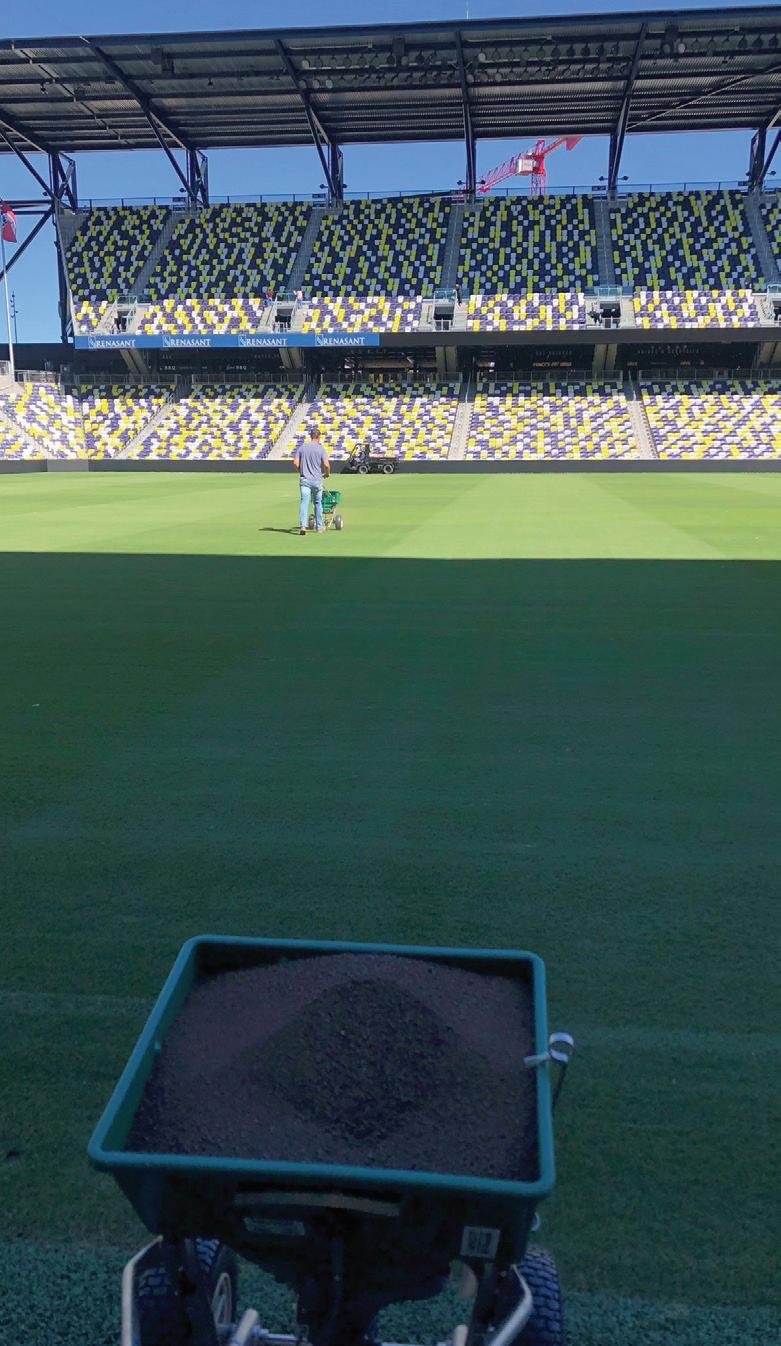

What is unique about your facilities now?

What makes them unique, but also what makes them tough to manage is right now we have three facilities in three different counties. We have our Academy facility in Brentwood where for the first three and a half years, that was where our first team trained. That was completed in October of 2019, and that’s when I started so that was completed before I got here. That was my first facility I managed in Nashville. Then we have our stadium in Davidson County, in Nashville, and now our first team training facility in Antioch.

Our brand is spread out throughout the Nashville area, so we touch a little bit of every part of Nashville. Which is good, it gets the brand out there, but managing all three facilities when they’re anywhere from 30–40 minutes apart depending on traffic can be challenging at times.

What does your crew look like?

The crew is still a work in progress. We’re only at four and a half. Four full time, then a part- time, plus me. That’s probably my main priority going forward is to get us properly staffed. It’s been something I continue to work through with our organization. We have two full time groundsmen at Currey Ingram. We have a full time and a part time at Antioch, and then I have a full time hourly groundsman here at the stadium. Throughout the week, depending on demand, I’ll move from facility to facility. It’s a little hectic, but I think we’ll get there eventually.

What needs do you still have on your team?

It’s always good to get people with the professional background, but my first assistant, Alex Polnow, he’s a turfgrass graduate from Iowa State. He’s over Antioch, which is the first team training facility. My second assistant, Tran Zerface is at the Academy facility, and he graduated from North Dakota State. The community agreement is we’re going to prioritize hiring locally, so for our hourly guys, we’re looking more local in the Nashville area, so really we’re getting guys who maybe not have the turf background, but we’ve gotten guys from parks and rec, golf courses that are just good labor workers. We did get lucky on the last hiring go-around where we had a guy originally from Nashville, Dalton Stanley who was at Atlanta United for the last couple of years, he’s a turfgrass graduate from UT. We were able to bring him onboard because he was from the area, so that worked out in our favor.

The rest is just working with the organization and educating them on what it takes to properly maintain facilities and the actual workload. It’s not just mowing. We could talk for hours about what goes into managing fields at this level. The demand where the first team trains six days a week, we have academy that trains five to seven days a week. They have their games at the Academy facility, and this year we’re getting into concerts.

We have three concerts on the books, and it also sounds like we’re going to be opening up the stadium fields a little bit more to other private events. We had a wedding on the field this year already, we’re also doing Summerfest, so the demand’s only growing. Last year, with it being our first year in the stadium, we were kind of protective over the field, we just wanted to make sure we get in, get everything figured out, put a good product on the field. This year it sounds like we’re going to start opening things up to other non-soccer events on the stadium field.

How did everything hold up after all the events?

I was very impressed with the field last year. I felt like there was a learning curve, especially with this being my first time growing grass in a stadium with a 360 canopy. I’ve had grow lights before, we had them at Dallas, but I still have areas on this field that don’t see sunlight August. through mid-May. We have to figure out how we can manipulate and grow those areas with just grow lights. It was a quick learning process, we laid this out in March, and we really hit our stride in August, and that was about the time when you really saw this field responding well.

I think we had eight home games in nine weeks from end of July to first week of September. Then sprinkle some trainings in there, and from event to event, game to game, we were recovering and bouncing back. You couldn’t even tell we’d played the last week at that point. We started really dialing in our program and our maintenance schedule and our lighting rotation by August. You always think you’ve got it figured out until something else comes at you, whether it’s a concert or a cold snap. It’s always adapting, every year is different. In my nine years in MLS, there’s never been a year that’s been the same for growing conditions. You just get a base plan and go off that and adjust as the year goes.

When you first came to Tennessee from Dallas, did that feel like a big learning curve?

It was night and day. Dallas is in the transition zone, we’re in the north transition zone here in Nashville. In Dallas, when you get ready to pull the plug on ryegrass, you’re getting consistent 90s, and it’s going to reach 100 degrees where that bermudagrass just jumps. It takes off and it doesn’t stop. Here, I feel like you might get a week in the 90s, if you’re lucky, in May. I don’t know if that has happened since I’ve been here. But even in June you might hit 90s and then that next week is going to be 80s or 70s, then that ryegrass comes firing back. In Dallas, we never chemically sprayed out ryegrass, we could always do it culturally. Whether it’s scalping, verticutting, pulling cores, watching our water – that ryegrass is going to go and the bermudagrass is going to take off.

My first year here in 2020, I tried to run the program we did in Dallas to transition, and I lost, so I ended up having to spray out the ryegrass. I think it was around 4th of July where I just couldn’t get the ryegrass to finally back off, so we ended up spraying it out. We had a pretty successful transition, then the next summer

(2021), I think we had four weeks in the 90s. One in June, one in July and two in August. It’s been more difficult, especially in regards to the transition window, it’s been a lot harder to get the Bermuda up and going here than it was in Dallas.

The disease pressure is a lot higher here, I’ve noticed. Where in Dallas, I think the five years I was there, I never sprayed one fungicide on my training field. We’d spray fungicides, and put blankets out when we were putting flooring down. Here, you have to be on a preventative schedule maintenance, otherwise you’re going to get caught. That was the big part of the learning curve, just different climate. You’re still in the transition zone, but you don’t get the benefits of being in Dallas, where it’s hotter, it’s dryer, less humid. I’ve learned a lot the last four years for sure, growing grass in Tennessee.

Did you join TTA pretty soon after moving here?

It was one of the first things I did because I wanted to get my applicator’s license, and I did that through TTA. I wanted to start my networking, the best way to learn how to grow grass in an area is to talk to other turfgrass managers, so I joined the organization just to meet people and get that license and start learning as much as I could on the difficulties and challenges of growing grass in Tennessee.

I knew John Sorochan before I came to TN. I’ve had multiple conversations with him about things I’ve seen out here, and what to do, timing for your pre-emergent applications in Tennessee versus Dallas. I had my first run-in with nematodes in 2021. I’d never had a nematode, never seen it. I couldn’t figure it out. I’d solved the issues I was having on the grass fields out at Currey Ingram, but we were trying some things to correct it, and just couldn’t get it corrected.

1.

•

•

•

2. Where is it used?

• High demand athletic fields: football, soccer, baseball, softball, and rugby.

• High traffic areas: Horsetracks, goalmouths, and tournament crosswalks.

I think I was having a conversation with Eric Holland with Precision Turf one day, and he was explaining to me about another field in Florida. He explained exactly what was going on in my field, so we took a nematode assay and came back and we were in threshold of damage. We sprayed a nemacide and moved forward.

That, and also armyworms. I hadn’t seen that until I was in Tennessee. We’ve had that a few rounds now, 2021 was a rough year. I was just walking the field at Currey, and I saw the worm and I recognized it right away. We got on top of it and didn’t have any damage from armyworms here.

Tell us about your family and what you do in your free time.

I came down here and it was just my wife and I. Since then we welcomed a little girl who’s now two years old. We are growing here in TN. We bought a house in Spring Hill and we do really enjoy life here. We live in a really good neighborhood, we know all of our neighbors and there’s front driveway hanging out or back patio hanging out with them.

As we find time off, we do like go exploring, whether it’s hiking, or going to all the waterfalls around. We still haven’t made it up to Gatlinburg yet, it’s on the to-do list.

You’ve spent most of your turfgrass career in soccer. Was that because of your love for the sport or just job opportunity?

It was job opportunity. When I applied for the FC Dallas job, just seeing FC Dallas, I had no idea what it was. What I knew of Dallas’s professional soccer was Dallas Burn. So when clicked on the link and saw that it was professional soccer, I had no experience in soccer at this point, so I just applied for it to see what the competitiveness in soccer was, salary-wise. It just so happened that my boss at Dallas also worked at the Rangers and knew the head guy at the Rangers really well, so I got a good referral from the Rangers and ended up at FC Dallas.

Now being in it nine years, I understand the game a little better, watching training every day. But I didn’t grow up playing soccer, I was into baseball and football. We do have good atmosphere here at Geodis Park, I think we average 28,000 fans a game.

The atmosphere alone is fun, and we’ve been in the playoffs every year since we’ve been in the MLS. Coach Gary puts out a great product year-in and year-out and it’s fun to watch.

What is one lesson you’ve learned the hard way in your career?

The hardest thing for me, especially starting here in Nashville, hiring people was learning to trust my assistants, allow them to be on their own and taking loads off my plate. I can’t be everywhere every day, so learning to let go of some things and let them handle it. They’ve made it easy to do that, they’ve done a great job handling their own facilities, so it’s taken a lot of work off my plate, but it was hard at first giving up that. I’m particular in how I do things and how I want things done, but learning that they might not do it the same way, but it gets done properly and at the end of the day it’s a good outcome.

What would be your advice for people entering the industry now?

My advice has always been internships. I think internships are huge. You’re going to figure out whether baseball or soccer is right for you. We started an internship in Dallas where we partnered with a golf course. Half the summer you were soccer, the other half you were golf, then we flipped the interns. That’s the time, when you’re in college, you don’t really have a lot of commitments, and you can move around the country. Figuring out what sport is right for you, whether it’s golf, football, soccer, baseball. It’s also the best way to get your name around. I tell interns all the time, when you intern for a club, you’re interning for every club out there. I know every head turf manager in soccer, I have most of them in my phone, where if I see somebody who applies for me, I’ll get a referral. I think internships are the most important thing to do to get your foot in the door or just to get your name around the organization.

ymbolism is great, but integrity is what matters. It’s a universal truth that confidence in a person or product sustains brand value, whether for automobiles, electronics, whiskey – you name it. With stiff competition in the marketplace and ne’er-do-wells pitching knockoffs, the integrity of a product and faith in the people behind it cannot be faked, undercut or understated.

So it is with turfgrass. A certified cultivar is more than just grass – it’s turfgrass with integrity.

Consider Tiffany & Co. For nearly 200 years, Tiffany’s little blue box has been its statement of quality, even before the fine jewelry inside is visible. The distinctive, trademarked “Tiffany Blue” creates breathtaking anticipation because of the integrity of its brand: sought-after elegance, renowned craftmanship and international prestige.

Tiffany’s marketing slogan? “Who said red is the color of love?”

Such stature is earned.

Tiffany’s fine jewelry is usually reserved for special occasions then carefully stored away until the next wear. Consider the expectations, then, for a product undergoing regular use. One visible for all to appreciate on a daily basis. Should your expectations for turfgrass be anything less?

Choosing a top turfgrass cultivar and utilizing a robust, respected certification program solidifies the integrity of the cultivar and the brand of the farm that produced it. Such trustworthiness is at the core of integrity. It takes years to earn it but can easily be lost.

Validation of your trustworthiness must be constant. Doing so will increase the value of your products and your business – it means everything. It is your “blue box” of consumer anticipation.

“You’re either elite or you’re not,” says University of Georgia Head Football Coach Kirby Smart. A certified winner himself, Coach Smart should know.

What’s the value of certification for turfgrass? According to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, a certification mark shows consumers “that particular goods and/or services, or their providers, have met certain standards.” In short, certification by the state crop improvement association provides a process attesting to a level of achievement.

So it stands that obtaining and protecting the integrity provided by turfgrass certification can make a sod grower elite. The process adds value and elevates the product to a higher level. Not only that, but turfgrass certification validates being invested in industry oversight that solidifies your integrity as a producer.

Not all turfgrass cultivars can be certified by the state crop improvement association because the rigorous comparative evaluation standards and scientific peer review can’t be met, but those that can, should.

The ultimate responsibility for protecting the purity of a turfgrass cultivar lies with the grower, through farming practices. Turfgrass certification is not just for the grower, however. It is also a commitment to grow the best, backed by rigorous third-party oversight, to assure the earned integrity customers are seeking. State authorities, as appropriate, and licensees of the cultivars also play a critical role in this process of achieving and maintaining integrity. There is no substitute, and presenting such certification to buyers and end-users demonstrates these products are the best the market has to offer; that you stand behind your product. Remember, you’re either elite or you’re not.

Each state operates a Crop Improvement Association Certification (CIAC) program. The blue tag of these crop improvement associations is the ultimate quality control marker for warm season, vegetatively produced turfgrass cultivars. Blue tag validation shows landscapers, contractors, and consumers that the sod meets all state CIAC rules and regulations.

No blue tag means “no certification.” While its absence is not necessarily a sign of a bad actor, the CIAC blue tag serves as a warranty by preventing the sale of turfgrass varieties in the certification program when contamination is documented and not properly rectified.

“Certification is the highest quality classification in our industry,” asserts Charles Harris, the CEO and co-founder of Buy Sod, Inc.

Buy Sod operates sod farms in five states and is enrolled in the CIAC program in each because Harris sees the added value of a high confidence level in quality turfgrass for his company and customers: “It validates the best products of the highest quality. That’s where we want to be.”

“I believe CIAC is the standard for what it means to achieve the best quality plant material,” says Harris, whose company is based in Pinehurst, NC. “These inspections have teeth. They matter.

Professionals in turf management as well as consumers have high expectations that can only be met by a rigorous certification process. We are proud to support and participate in these initiatives. It’s a differentiator and makes us better.”

Multiple paths lead to increased integrity. Certification and inspection programs by agribusinesses license turfgrass cultivars as they move to commercial production. Genetic purity is essential at each step, from breeder, to foundation, to nursery, to production.

The Turfgrass Group is among the licensers of turfgrass cultivars. The Cartersville, Ga., organization’s commitment to excellence ensures its licensed growers – “Certified Growers” – are in a position to be elite. Bill Carraway, Vice President of Sales and Marketing with The Turfgrass Group, Inc. proclaims, “Certification is a fundamental imperative by which we operate. Maintaining the genetic integrity and provenance of our cultivars is what sets us apart.”

That commitment starts with complying with respective state certification standards and licensing a limited number of certified producers. Farm visits, inspection, and quality control reviews throughout the production process are all mandatory, critical steps in the process.

Dr. Brian Schwartz is a professor of turfgrass breeding and genetics at the University of Georgia. As one of the nation’s top turfgrass breeders, Dr. Schwartz is on the patent for at least three turfgrass cultivars. His resume includes a Ph.D. in plant breeding from the University of Florida and a B.S. and M.S. from Texas A&M University.

It’s no surprise this scientist looks even beyond the assurance of the CIAC blue tag and hones in on certification as preservation of the research process.

“When properly implemented and enforced, it stops problems,” Dr. Schwartz says. “Investing in a breeding program to develop emerging cultivars only makes sense if steps are being taken to protect them from contamination. I believe in the certification system. I know it delivers the highest quality product with the most value. It is the only way to protect the integrity of plant performance over time.”

Integrity represents a reputation for hard work and excellence. For turfgrass, certification is the outward demonstration of an internal commitment to integrity. It is Tiffany’s “blue box” and eliminates “seeds of doubt.”

José Javier Vargas Almodóvar Research Associate II

Turf & Ornamental Weed Science

The University of Tennessee 2431 Joe Johnson Drive 252 Ellington Plant Sci. Bldg. Knoxville, TN 37996 (865) 974-7379 jvargas@utk.edu tnturfgrassweeds.org @UTweedwhisperer

Greg Breeden Extension Specialist, The University of Tennessee 2431 Center Drive 252 Ellington Plant Sci. Bldg. Knoxville, TN 37996-4561 (865) 974-7208 gbreeden@utk.edu tnturfgrassweeds.org @gbreeden1

Jim Brosnan, Ph.D. Associate Professor, Turfgrass Weed Science

The University of Tennessee 2431 Joe Johnson Drive 252 Ellington Plant Sci. Bldg. Knoxville, TN 37996-4561 (865) 974-8603 jbrosnan@utk.edu tnturfgrassweeds.org @UTturfweeds

Kyley Dickson, Ph.D. Associate Director, Center for Athletic Field Safety Turfgrass Management & Physiology (865) 974-6730 kdickso1@utk.edu @DicksonTurf

Frank Hale, Ph.D. Professor, Entomology and Plant Pathology

The University of Tennessee 5201 Marchant Drive Nashville, TN 37211-5201 (615) 832-6802 fahale@utk.edu ag.tennessee.edu/spp

Becky Bowling Turfgrass Extension Specialist The University of Tennessee rgrubbs5@utk.edu @TNTurfWoman

Brandon Horvath, Ph.D. Associate Professor, Turfgrass Science

The University of Tennessee 252 Ellington Plant Sci. Bldg. 2431 Joe Johnson Drive Knoxville, TN 37996 (865) 974-2975

bhorvath@utk.edu turf.utk.edu @UTturfpath

John Sorochan, Ph.D. Professor, Turfgrass Science The University of Tennessee 2431 Joe Johnson Drive 363 Ellington Plant Sci. Bldg. Knoxville, TN 37996-4561 (865) 974-7324 sorochan@utk.edu turf.utk.edu @sorochan

John Stier, Ph.D. Associate Dean

The University of Tennessee 2621 Morgan Circle 126 Morgan Hall Knoxville, TN 37996-4561 (865) 974-7493 jstier1@utk.edu turf.utk.edu @Drjohnstier

Alan Windham, Ph.D. Professor, Entomology and Plant Pathology

The University of Tennessee 5201 Marchant Drive Nashville, TN 37211-5201 (615) 832-6802

https://ag.tennessee.edu/spp/ @UTPlantDoc

By Daniel O’Brien, Wendell Hutchens Ph.D., Mike Richardson Ph.D.

Atthe risk of stating the obvious, water matters. In an increasingly crowded world, with increasingly strained resources, this is true for all walks of life and turfgrass is no exception. Decisions about how we use, and just as importantly, how we conserve water are major issues for turfgrass professionals, which is why such decisions are also at the heart of our Turfgrass Research Program at the University of Arkansas. Exploring new ways to maximize this most vital resource has been, and continues to be, a top priority in the work we do.

When it comes to managing water, one of the best resources available to turfgrass professionals are wetting agents, also known as soil surfactants. Yet, as powerful and versatile as these products are, the truth is that in many ways, turfgrass research is just scratching the surface in our understanding of them and how they work. While wetting agents are by no means a “silver bullet” for solving all the water issues facing the future of turfgrass, they do hold tremendous potential for a range of moisture related issues, such as: preventing localized dry spot, improving moisture uniformity, increasing water infiltration, prolonging rootzone moisture retention, reducing winter injury, and enhancing the efficacy of fertilizers and pesticides (Abagandura et al., 2021; DeBoer et al., 2020; Hutchens et al., 2020; Jacobs & Barden, 2018).

Building on that existing body of research, we are thrilled that a recent proposal of ours was selected by the Golf Course Superintendents Association of America (GCSAA) Foundation as a recipient of the 2023–2024 Dr. Michael Hurdzan Research Grant Endowment. The Hurdzan Endowment is dedicated to, “funding applied environmental research on golf courses, with the specific goal of reducing requirements for water, fertilizer, pesticides, or fossil fuels in golf course maintenance.” Above all, it is important to us that our research is both novel and practical, offering meaningful benefits to turfgrass professionals. In this case, those turfgrass professionals are golf course superintendents, and the potential benefits include savings, both in terms of water and money.

AIMAGE 1 New wetting agent research at the University of Arkansas will compare different wetting agent products, application rates & timings, as well as different technologies for assessing wetting agent performance in sand-based putting greens. Individual plots can be clearly seen from drone images (A) immediately after application, and even more so (B) during post-application irrigation (0.2").

Essentially, this research boils down to the simple question, How do you get the most out of a wetting agent application? At the University of Arkansas, we have been studying wetting agents for over 20 years, but we will be the first to tell you, there are still a lot of unknowns when it comes to these extremely important products. Because wetting agents are not subject to the same registration process or labeling requirements as pesticides, companies do not have to disclose precise active ingredients or extensive amounts of research data in order to begin selling a product. While all of that is beyond a superintendent’s control, what is very much within their control is: which wetting agent to use, how much product to put in the tank, and how often to apply. The overall goal of this research is to investigate wetting agents at the place where superintendents can exercise the most control over product performance. To do that, our original question can be broken down into comparisons on three distinct levels: 1) comparisons among wetting agents, 2) comparison among application rates/timings, and 3) comparisons among technology for evaluating wetting agent performance and longevity.

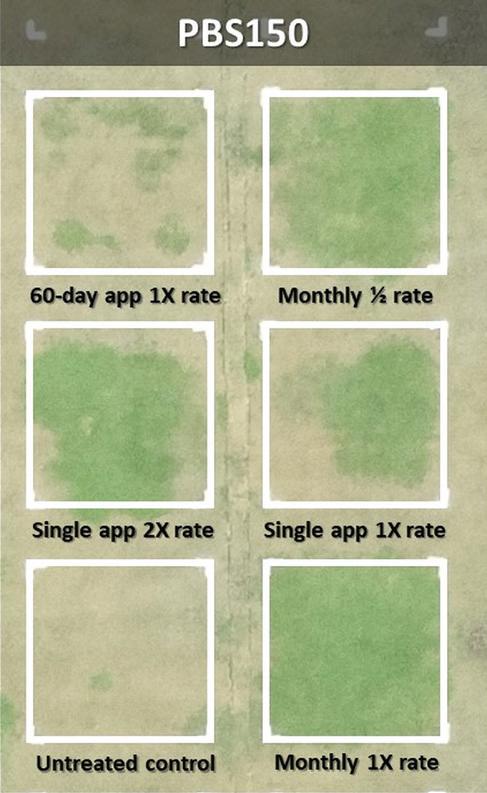

Starting with comparisons among wetting agent products, we opted to work with six different wetting agents, each from a different manufacturer (Table 1). Admittedly, there are many options available, but in research you seldom have space/time to test everything at once. Our criteria were based largely on conversations with superintendents about wetting agents they were using, along with a desire to include products marketed both for monthly reapplications, as well as those for “long-term” or “season-long” effectiveness from a single application.

Second, comparisons among application rates/timings were based on the fact that when it comes to wetting agent labels, it’s common to see multiple options for application amounts and intervals. While flexibility is inherently a good thing, it does not mean that all options perform the same. When looking at each wetting agent individually, we wanted to evaluate which application rate/interval produced the best turfgrass quality above ground, with the greatest volumetric water content (VWC) in the rootzone.

We applied each of our six wetting agents six different ways (including a nontreated control). To maintain the ability to compare different products, it was important that the six different “application strategies” shared some common features (Table 2). Generally, it can be said that two of the application strategies were season-long applications, two were monthly reapplications, one was a reapplication every two months, and one was zero product applied (nontreated control).

Long-term 1 Season-long application at a standard label rate

Long-term 2 Season-long application at an increased / high rate

Monthly 1 Reapplications every 4 weeks at a standard, label rate

Monthly 2 Reapplications every 4 weeks at half the monthly rate

Bi-monthly Reapplications every 8 weeks at a standard, monthly rate

Nontreated

615-383-0206 orders@SigmaTurf.com

For each individual wetting agent, the specific rates/timings started with what was listed on the product label and when necessary, additional rates were calculated to ensure that each product met the general guidelines for each of the six application strategies. Specifically, the questions we were interested in: with season-long applications, does more product lead to increased performance and/ or longevity? And for repeat applications, can we create cost-savings and still achieve the same level of performance with reduced rates or extended intervals between applications?

Finally, the third comparison was not about wetting agents themselves as much as it was the technology/methods used to evaluate how well they are working. Our research program continues to use portable moisture meters such as the TDR 350 (Spectrum Technologies Inc.) extensively for studying wetting agents. We have also begun incorporating installed wireless moisture sensors such as Turf Guard (The Toro Company) for continuously monitoring VWC (as well as soil temperature and electrical conductivity). Along with both of these devices, we also use an onsite weather station to calculate potential evapotranspiration (ETo) and growing degree days (GDD). Bringing all of these technologies together allows us to ask the underlying question, what is the best way to track wetting agent performance and determine when reapplication is necessary? Ultimately, understanding when and why wetting agents stop working can lead to more informed decision-making about how often (and how much) to apply.

IMAGE 2 Within each plot (3' x 3') volumetric water content will be measured weekly using portable moisture meters at 1.5" and 3.0" (nine measurements per plot at each depth), and continuously using wireless sensors at 1.0" and 6.0" (one sensor per plot in selected plots).

IMAGE 3 Wireless sensors can be installed relatively easily to continuously monitor volumetric water content and help identify the point when wetting agent applications are no longer effective.

The experimental area is located on a block of ‘Tyee’ creeping bentgrass, within a USGA sand-based research putting green in Fayetteville, AR. Initial treatment applications were made on May 10th, 2023, will continue throughout the summer months, with final applications scheduled for Aug. 30th. Data collection which includes TDR measurements (1.5” and 3.0” depths), drone images, firmness measurements, and visual assessments of turfgrass quality and percent localized dry spot, began six days after initial application and will continue weekly through Sept. 7th. Turf Guard wireless sensors were installed to measure VWC at 1” and 6” below the putting surface. So, while it is still early in the 2023 research season, preliminary work conducted in 2022 has

shown promising results for separating different application strategies both within and across wetting agents.

If you’re still reading, hopefully that is because something about this research appeals to you. If you are interested in learning more about it, we want everyone to know that the University of Arkansas Turfgrass Field Day will take place Tuesday, August 1st, 2023, at the Milo J. Shult Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Fayetteville, AR. You are all invited, and this research will be featured prominently.

In the meantime, if you would like to talk wetting agents or anything else turfgrass related, please don’t hesitate to reach out. And please remember that this work is made possible by the generous support of the GCSAA Foundation and multiple GCSA Chapters in and around the state of Arkansas.

IMAGE 4 Previous research at the University of Arkansas has observed notable differences in wetting agent performance among various products, as well as among different rates and timings of the same product. The current research will build on previous work with the goal of helping superintendents identify effective combinations of application rate/timing for individual wetting agents. 3 August 2022

This research is made possible by financial support from:

• Golf Course Superintendents Association of America Foundation Dr. Michael Hurdzan Endowment

• The Arkansas Chapter of the Golf Course Superintendents Association of America

• The Mississippi Valley Chapter of the Golf Course Superintendents Association of America

• The North Texas Chapter of the Golf Course Superintendents Association of America

• The Ozark Turf Association Chapter of the Golf Course Superintendents Association of America

Special thanks to our research cooperators:

• AQUA-AID Solutions

• Aquatrols Corporation of America

• J.R. Simplot Company

• Mitchell Products

• Precision Laboratories

• Target Specialty Products

Additional thanks to:

• The University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture

• Professional Turf Products

Daniel O’Brien is a Ph.D. candidate in the Turfgrass Science Program at the University of Arkansas working under Dr. Mike Richardson • dpo001@uark.edu

Wendel Hutchens Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor of Turfgrass Science in the Horticulture Department at the University of Arkansas • wendellh@uark.edu

Mike Richardson Ph.D. is a Professor of Turfgrass Science in the Horticulture Department at the University of Arkansas mricha@uark.edu

Abagandura, G. O., Park, D., Bridges Jr, W. C., & Brown, K. (2021). Soil surfactants applied with 15N labeled urea increases bermudagrass uptake of nitrogen and reduces nitrogen leaching. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, 184(3), 378-387.

DeBoer, E.J., Karcher, D.E., McCalla, J.H., Richardson, M. D. (2020). Effect of late-fall wetting agent application on winter survival of ultradwarf bermudagrass putting greens. Crop, Forage and Turfgrass Management, 6(1), 1-7.

Hutchens, W. J., Gannon, T. W., Shew, H. D., Ahmed, K. A., Kerns, J. P. (2020). Journal of Environmental Quality, 49(2), 450-459. Jacobs, P., & Barden, A. (2018). Factors to consider when developing a wetting agent program: A one-size-fits-all approach to developing a wetting agent program is not possible. USGA Green Section Record, 56(9), 1-6.

By Neal Glatt, CSP, ASM

any leaders seek to hire people who fit their company culture, meaning they choose candidates who share their values, style, or goals. Their theory is that these teams will be more cohesive and aligned to enable performance of key business outcomes. Unfortunately for these leaders, the science shows exactly the opposite is true.

According to a 2015 McKinsey report, diverse management teams are 35% more likely to outperform non-diverse teams in terms of financial performance. One of the reasons for this is that teams which disagree challenge each other to perform at their best. The desire for cohesiveness can in fact limit a team’s ability to obtain performance.

For managers who want to hire the best people, cultural fit may be undermining the entire hiring process. In fact, personality, behavioral, or cultural tests predict on-the-job performance only 20% of the time while giving hiring managers a false sense of security.

One way to know that hiring methods aren’t working to look at the employee turnover rate of an organization. What percentage of employees departed your organization for any reason in the past 12 months? If the answer is 9.2% or higher (the average for all construction companies), then your hiring criteria must be revaluated to outperform the competition.

The best leaders don’t look for a cultural fit, they target candidates who contribute cultural adds. These people have an identity, viewpoint, or experience which is new and unique to a team and brings a new perspective to an organization. Striving for diversity, as opposed to fit, is the best way to build a highperforming team with lower turnover.

A good talent assessment won’t reveal work styles because the best in each role achieve their results in very different ways. Save the personality and behavioral assessments for building self- and others-awareness of new hires and development. In the hiring process, an assessment of the entrepreneurial talent is what’s needed to succeed.

Finally, managers need to revisit how they interview and move to structured formats where each candidate is given the same questions and answers are scored against an objective guide. These questions should also only be around exhibited behavior in previous experiences or hypothetical situations to determine how someone would perform in a given role. When combined, these strategies dramatically reduce hiring bias and increase team talent and diversity.

If you need more help revamping your hiring process to succeed, check out the courses on GrowTheBench.com or contact us for one-on-one coaching.

Neal Glatt is the Managing Partner of GrowTheBench, an online training platform for the green industry. Connect with Neal at www.NealGlatt.com.

members in the industry through education, promotion and representation. The statements and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the association, its staff, or its board of directors, Tennessee Turfgrass Magazine, or its editors. Likewise, the appearance of advertisers, or Turfgrass Association members, does not constitute an endorsement of the products or services featured in this, past or subsequent issues of this quarterly publication. Copyright © 2023 by the Tennessee Turfgrass Association. Tennessee Turfgrass is published bi-monthly. Subscriptions are complimentary to members of the Tennessee Turfgrass Association. Third-class postage is paid at Jefferson City, MO. Printed in the U.S.A. Reprints and Submissions: Tennessee Turfgrass allows reprinting of material. Permission requests should be directed to the Tennessee Turfgrass Association. We are not responsible for unsolicited freelance manuscripts and photographs. Contact the managing editor for contribution information. Advertising: For display and classified advertising rates and insertions, please contact Leading Edge Communications, LLC, 206 Bridge Street, Suite

Franklin,

37064, (615) 790-3718, Fax (615) 794-4524.