4 minute read

Stafford in 3D

Printing firm delivers for businesses and ‘three-letter agencies’

BY ERIC ALTHOFF

Bruce LeMaster wasn’t looking for a corporate overseer for his 3D printing firm, Applied Rapid Technologies, or ART – but opportunity, as it sometimes literally does, came knocking in the form of Obsidian Solutions Group, a defense contractor based in Fredericksburg.

LeMaster relates that Obsidian, which contracts with the State Department, was seeking to get into “additive manufacturing.” And rather than start from scratch, it wanted to acquire a company such as ART that was already involved in 3D printing.

Obsidian co-founder and CEO Tyrone Logan and president Jim Wiley popped by LeMaster’s office for what he assumed was a social visit. But they soon inquired whether Lemaster would be willing to sell. At first, LeMaster said, he wasn’t interested in selling the business he’d started in 1996.

“We stayed in touch,” LeMaster said recently. “This was all in 2019, and then COVID happened.” He eventually decided in the summer of 2020 to sell, and the deal closed that October.

With ART now a subsidiary of Obsidian, LeMaster continues to function as its vice president of manufacturing. Little has changed since the sale, he says, and the company continues to 3D print parts for the automotive, medical, consumer appliances and aerospace industries – as well as for the government.

LeMaster, who lives in the Hartwood District of Stafford County, explains that 3D printing is simply another name for the term “additive manufacturing.” Before 3D printing, most manufacturing involved subtracting from a block of material to “remove what you don’t need.”

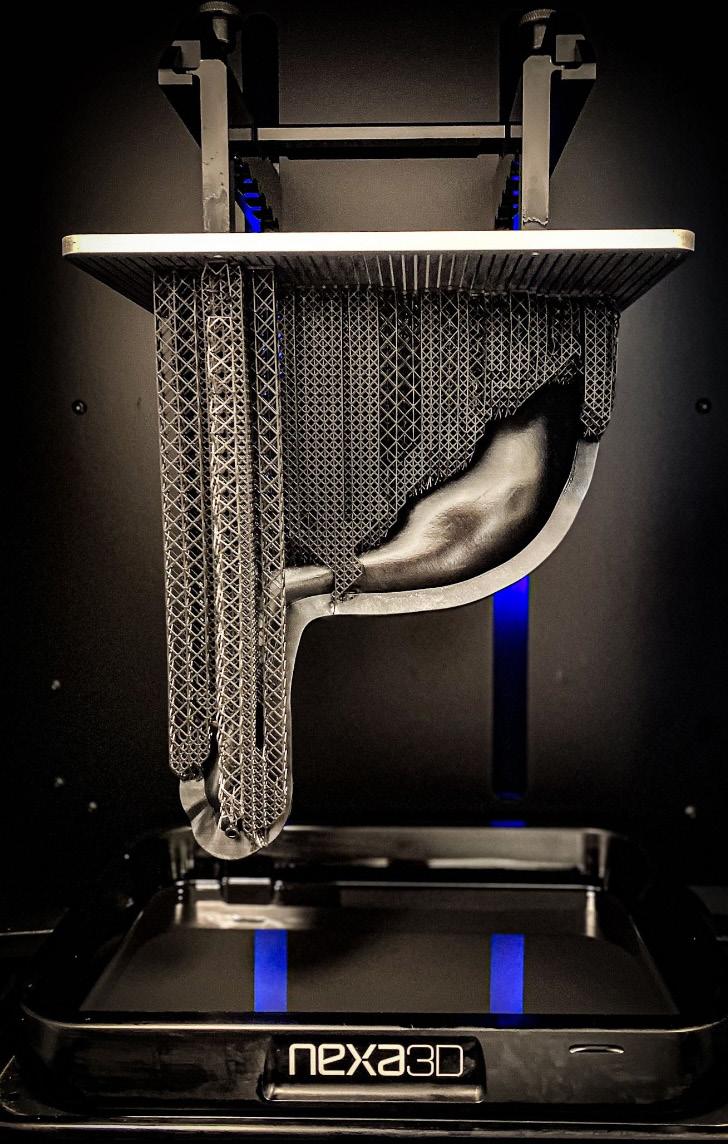

Additive production “starts with nothing,” in LeMaster’s words. A printer fires lasers into a vat of liquid to turn a portion into a solid. Layers and layers are subsequently added on top of one another in a technique known as stereolithography.

The laser essentially draws “one cross-section of a part,” LeMaster explained. “An elevator would drop down into the vat of liquid, and fresh resin would coat the layer that was just created. We would draw the next layer and bond it to the previous. And when the part is done, it rises up out of the vat of liquid, and there is a 3D solid model there.”

The technology has been around since the 1980s, LeMaster said, but thanks to a proliferation of inexpensive 3D printers during the 2010s, the process of stereolithography was essentially replaced by another technique called fused deposition modeling, or FDM. LeMaster likens FDM to the application of a hot-glue gun.

“You feed a filament of plastic into a hot nozzle, melt it and you extrude the cross-section that you’re trying to create,” he said. “It keeps drawing successive layers until the part is complete.”

If that all sounds a bit technical, what isn’t is the relationship ART continues to enjoy with “a lot of those three-letter agencies,” as LeMaster puts it.

While he can’t reveal certain aspects of his company’s defense contracting work, LeMaster said his firm does indeed 3D-print missile and tank parts. However, it also makes such ordinary items as blenders, toasters and coffee pots. From those liquid vats, ART also pops out all manner of medical appliances, from liposuction devices to DNA “sorting equipment.”

Among ART’s local customers, Al Erkert, owner of Web Equipment in Fredericksburg, said he has frequently called upon LeMaster’s expertise to construct out-of-stock parts for older forklifts. Many of those machines are decades old and often require specific pieces that are difficult to source.

“When I can’t get enough of those used parts that are salvageable and repairable, then I have to go looking for other sources,” Erkert said. “I was able to get parts that were fully functional and indispensable from the factory OEM.”

He added that LeMaster’s customer service ensured that Web Equipment would continue to work with ART.

“When the quality wasn’t right, they took it back and either fixed it or remade parts,” Erkert said. “I pay him on time and he makes the parts on time.”

John McQuiddy, president of McQ Inc. in Fredericksburg, has worked with LeMaster for three decades. McQuiddy praised ART’s ability to “accurately manufacture a product package” for McQ’s prototype security sensors, which are sold to commercial customers as well as to the Department of Defense, the Secret Service and the Department of Energy.

ART takes the McQ 3D design and turns it into a prototype that is identical to the final product for testing purposes, McQuiddy said. “McQ products are very advanced technology, and therefore require the latest mechanical design and fabrication.”

Among the services ART provides are supplying the mechanical structure for McQ’s electronic sensors so that they aren’t damaged when they hit the ground.

“Bruce keeps advancing ART mechanical design and fabrication technology to match the very latest 3D materials printing,” McQuiddy said. “He has always been a joy to work with.”

Indeed, LeMaster’s reputation is so established that his LinkedIn profile boasts the image of a dinosaur next to his name. It’s not a reflection of his age, he insists, but rather indicates membership in the Additive Manufacturing Users Group, an industry trade group that recognizes innovators such as LeMaster with its “Dino” icon.

“That’s our little special thing,” said LeMaster, who also serves on the organization’s board of directors.

LeMaster has been working in the Stafford area since 1987. In those simpler times (“There were two traffic lights on Route 17,” he recollects.), while living in a hotel, he worked installing a production line. After various moves away, he has called Fredericksburg home since 1992. He appreciates the area’s wineries, food scene and its proximity to Washington.

“Stafford County is very pro-business, and very much on the technology spectrum,” he said, adding that the location makes the county a natural fit for his type of work. “I can be in Pennsylvania, Maryland, North Carolina all within a few hours.”

LeMaster hopes ART will expand beyond the prototyping sector and continue growing in additive manufacturing.

“We’ve got some customers [for whom] we build 25 to 50 parts a month. So it’s not high volume, but we’re very competitive – and in fact we’re cheaper than most other processes when it comes to those kinds of numbers,” he said.

“With my high-speed printers…I can print a month to two months of production in 17 minutes. So it’s a very cost-effective solution.”