University

Horse Printing, San

EDITORS IN CHIEF Jordan Pollock Angela Yang

Adriana Carter Kavya Srikanth

POETRY EDITORS Lucy Chae

EDITORIAL STAFF Allison Argueta Matias Benitez Lishan Carroll Viva Donohoe Kyla Figueroa Shannon Gifford Anna Kiesewetter Ben Marra Malia Maxwell Divya Mehrish Kristie Park Nicole Segaran Cassie Shaw Pann Sripitak Katherine Wong Julia Wortman

Elizabeth Dunn

BOARD MEMBERS Olivia Manes Lily Nilipour Linda Ye

You’re about to encounter many distinct pieces of art. And while they are all unabashedly committed to delivering visceral images, striking insights and relevant assertions, they are also coquettish in nature. What I mean is, they ask for you, the reader, to do some work, to spend some time finding their truth. This may be a secretive character, or an extended metaphor, or purposeful ambiguity, or the personification of place, or the linguistic dissection and artistic exploration of the word “lying.” But they all ask the same thing of you, to read closely. And, ironically, they whisper, say the thing unsaid.

This is a challenge for us, the human race, to speak our truth. We are taught, with reason, to be cautious, to be vigilant, to anticipate negative responses and unintended harm, before we speak. And while this vigilance breeds order and social etiquette, it also presents an opportunity for things, important things, to go unsaid. Many of us–artists–are the most thoughtful and the most hesitant to disrupt, to speak up. And yet we do, in clever ways, in art. We say the things without really saying them.

We want to thank all of the clever minds we have worked with this past year, both contributors and editors. It’s been a pleasure to be granted access to the most precious parts of your mind.

Jordan Pollock and Angela Yang Editors-in-Chiefin the light, Robert Castaneros 8 An Ode to the Summer Quarter, a 1998 Toyota Corolla, a House in Louisville, and Grief, Robert Castaneros 10 Preceding a Summer Nap, Benjamin Marra 12 “What’s it like?”, Cassie Shaw 28 a ghazal called lying, Andrea Liao 43 You do it to make sure you’re awake

Grace Miller 44 San Francisco Earthquake, Elizabeth Grant 45

The Retreat, Jacob Langsner 16 the buffet, Emily Huang 31 Fish Bones, Kristofer Roland Nino 40

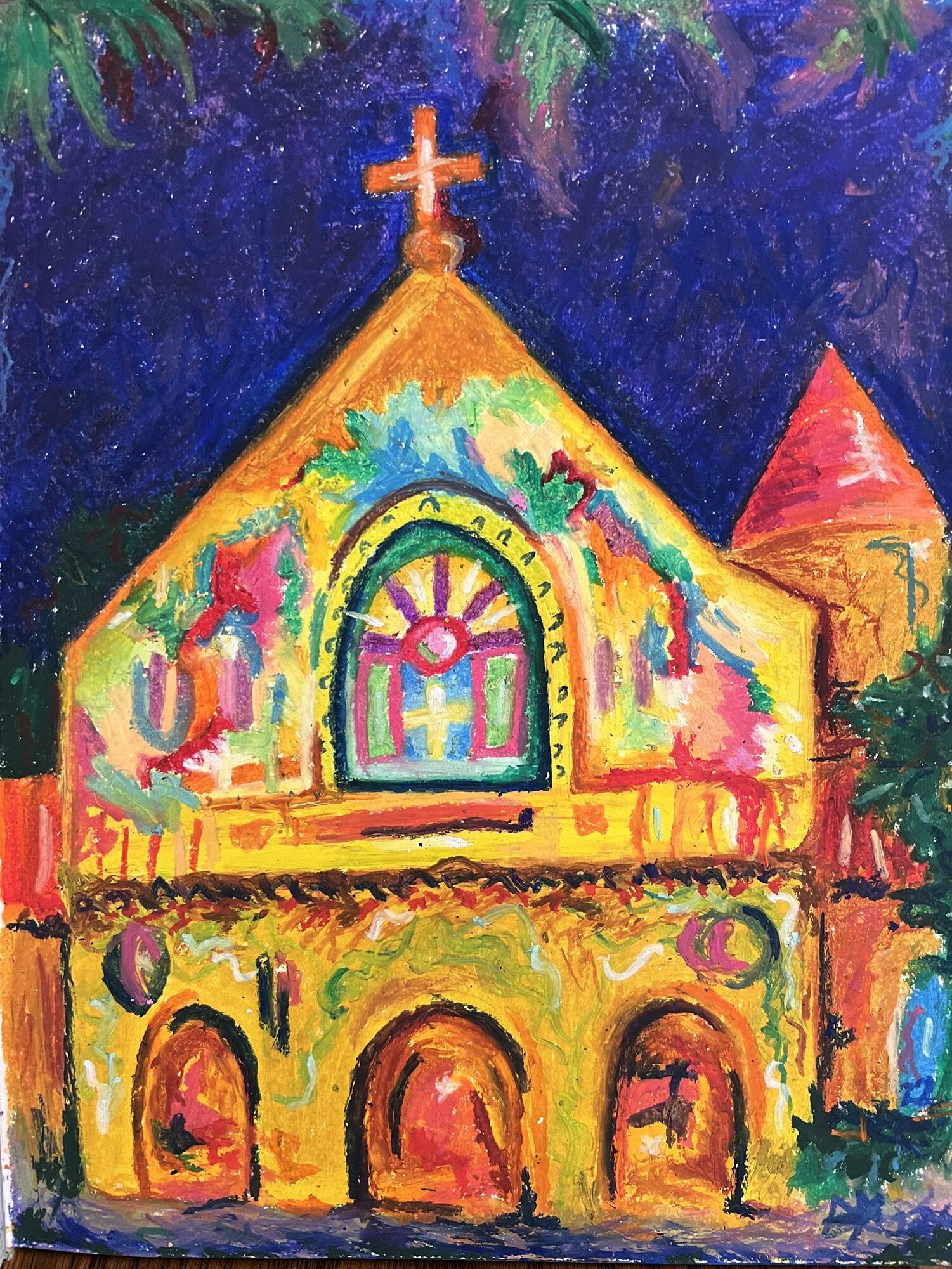

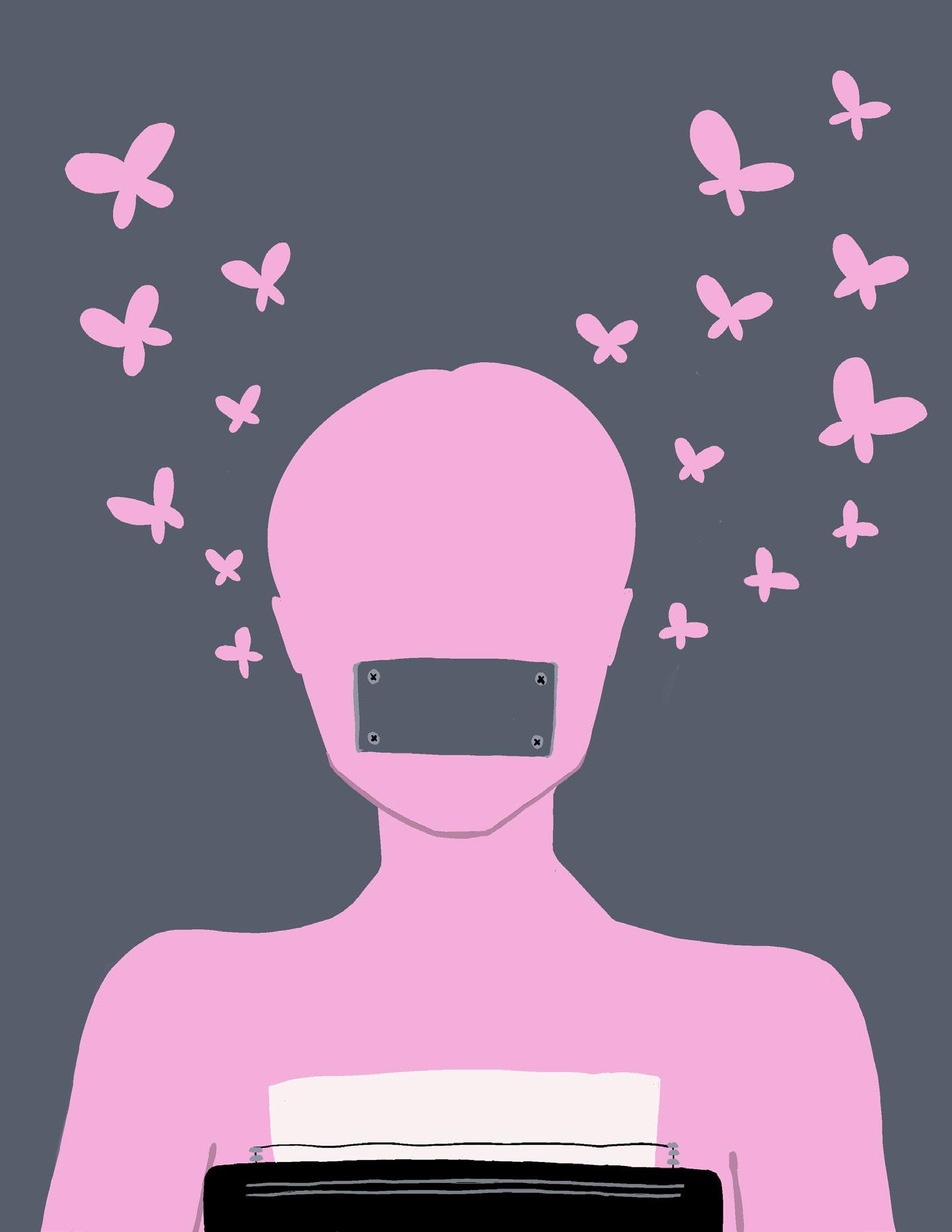

Cherry Grove, Allison Argueta 13 Refections at Mem Chu, Allison Argueta 14 11:26, Allison Argueta 15 All Eyes on You, Kristie Park 28 Speak, Jordan Pollock 30 Lemon, Jinhyo Huh 39 Sleep, Kristie Park 47

i am running into a new year / and i beg what i love and / i leave to forgive me. -Lucille Clifton

i am sitting in a restaurant in louisville with my living family, and i am saying goodbye to you in the only way i can: college-educated english. and i am regretful that i don’t have the bisaya to intellectualize how much i miss running my hands across your aging skin. / i have had this recurring dream where i am running into a blinding light, where the person i love is waiting for me in bed, wrapped in a blanket of her own forgiveness, a light where i am gifted with a new body, one that is not younger or thinner or birthmark-less, but kinder to itself. this year, i am still separated from your grave, but i see it so clearly in the light. and i watch my lola and my mother holding hands, sunbeams on their faces, and i hear them whisper goodbye to me as they sink into the ground, as i am begging them — in a language that is not theirs — to stay. / (mama, what kind of cruelty is this? after you, who is left of my family?) / in the light, i see a map of a country that is not yours, where all the people i love are anonymous dots, once clustered together, now spreading far apart, and i see that i too am an anonymous dot, living through my own history. / mama bella, i have decided that i will rush into this light and allow it to burn my

eyes. i will finally leave your body to rest in the earth. i will allow the roots of your pain and pleasure to make their way across my foreign country, and i will finally learn to forgive myself and the family that is still living — and i beg that you will forgive me too.

After Gwendolyn Brooks’ “We Real Cool”

There’s a strange joy in the way that we steal Nathan’s car. The way we grab the keys from his drawer and then we fly down El Camino Real. I mean it when I say this golden shitbox can fly, and it makes me cooler than the cool kids in high school — the ones who were sure of themselves — because, here, we can talk about hard feelings. The feelings that don’t fly, but linger until there’s nothing left. Like grief — like when Mama Bella dies in Kentucky, but you’re in California, so school assignments and tenuous friendships are the only thing left to grieve. And now we have no home in Louisville. No teleseryes, no broken exercise bike, just memory lurking in an empty house, where we once heard the laughs of the Banzon clan until late at night, and now it’s approaching midnight in quiet Palo Alto, and we fly on empty streets. I stick my head out the window, and the summer winds strike my face and ruffle my hair, as I think of all the ways I can tell it to you straight,

Hey, can we call tonight? I miss the sound of your voice, I miss the way we kiss, when our hands interlock the right way, and I miss how you sing to me when it’s just us and the silence, and I miss how I sing to you with sin-

-cerity, with grief. But the kind of grief that repairs itself, the kind of we-akness that makes me fly, away from a body that wanted to be thin, rather than loved, away from a body that filled itself with wine and beer and gin

when it craved warmth. And miraculously, I’ve found that safety in the way we whisper secrets to each other as we fly through suburban streets, a vehicular jazz, an improvisational way of comforting a friend while flying through intersections. June,

July, and August — I thank you for the love you showed us, when you proved that we could heal in unlikely places — in a 1998 Toyota Corolla that’s ready to die. Nevertheless, we fly — with such strange joy and peace — that we forget we die soon.

Light on the dusted surfaces of dry windows.

It really is beautiful somewhere out there. August afternoon, its deep, depleted sweetness, its loss beginning on the edges of the lawn where brown straw enters. But the trees rise up higher than I have ever seen them in my lifetime. Their distant tops vast neighborhoods of tan doves. It’s only that love has left a cloying taste in my mouth, turning sour as the days pass with no water, while the desert wind sweeps over the ocean and these blooming lands. Do I claim this world or not?

John was haunted by Mr. Coachley’s gut. It seemed the boss’s potbelly was trying to escape him. Perhaps the goodness left within was finally being digested: rare as caviar, and light as a buoy to adorn his pond of bile. Perhaps this was its last attempt at freedom. John could see it happening like the classic scene from Alien, but in reverse. Mr. Coachley already looked like a toad, and from his paunch would burst a little human yelling wait! I’m still here! And still, John thought, any freed virtue would die in the dirt. It would certainly find no home in Francis, who sat with mock resolve beside Mr. Coachley and his eager bulge.

The two men cast each other in sharp contrast, sitting on a weathered log at the brink of a fire they paid someone else to build. The trees beyond the firepit glowed faintly, then faded into total darkness—a blackness made deeper than the night, as it blossomed at the border of the blinding flames. And in this portrait of opposites, of dark and light and nothing in between, it seemed nature had belched from its void the two poles of humankind: one squat and wanting nothing. The other lean, and hungry for it all.

John watched Francis move in. The younger man slid toward Mr. Coachley as a handsome moth drawn steadfast to corporate fluorescence. He rubbed his chin as Mr. Coachley waxed poetic over golf and human conquest. The act was layered: a show of attention played with Shakespearean gusto, and a clever guise to check his stubble. Doubtless there had been a calculation—some golden ratio, finely mixed to paint a hue of rustic grit without smearing the long-worked portrait of an office superstar. But then he fumbled. John concealed a smirk as Francis

began a joke about the Red Sox, then abruptly changed the topic to birdwatching after realizing Mr. Coachley actually liked the Red Sox, and it was the Mets he couldn’t stand.

As Francis chirped, Ralph remained plastered to the log across the flames. He sat tightly next to John, like a frozen stick of butter slowly melting beside the campfire. John felt obligated to acknowledge Ralph partly because they were sharing a log, and partly because Ralph deserved pity for the general misfortune of being Ralph. Where Francis bristled with the muscles of a man who put as much rigor into his body as he did his empty shows of kindness, Ralph was little more than bone. He was too weak to carry the type of weight all too often placed on people who act out of kindness that isn’t performed. And so, with a feeble note of friendship, John whispered to Ralph that Francis would have to lean even closer if he really wanted to kiss Mr. Coachley’s ass. Ralph returned a short laugh that somehow felt like a question. He reached to fidget with his tie, only to realize that for once, he wasn’t actually wearing one.

On a separate log, Camille sat alone. When a cloud of ash concealed her finer parts from Mr. Coachley’s gaze, she checked her phone for bars then quietly pouted.

On the hike that afternoon, John had been the only one to notice Camille had disappeared into the rain. When he found her, John hid behind a redwood and watched her chain-smoke cigarettes. The smoke and rainy fog had mixed, and pooled around her head like the old cartoons where someone snaps, and livid steam starts to jet from their ears. When Camille turned, her face was stained with tears.

John had not expected crying. In a panic, he motioned to the cigarettes and said:

“Those are going to kill you one day.”

“You have no idea,” Camille replied.

John paused, thought he’d rather not know any more, and then asked for a cigarette of his own.

Camille sighed. “Trying to die with me?”

“Just wouldn’t want to live in a world without you,” John replied.

A queasy silence followed. John immediately regretted the statement. He sat in the wet leaves and decided to fake interest in a bird that was not actually there. When the quiet burned, John said something even worse:

“I’m sorry I never called again.”

Camille froze. She pursed her lips and focused on the same imagined bird.

“That was three years ago,” she replied.

Then, by some dazed miracle, Camille began to laugh. The sound was primal, and John quickly joined as it built to howls. Until the rain stopped, they sat on the forest floor and stewed together in a sort of wounded relief. When he was younger, John had wanted to be an astronaut. This sour flood of comfort on the forest floor was the closest he would ever get to feeling like he landed on the moon.

Back at the campfire, Ralph cleared his throat. John caught himself watching Camille again: a soft grimace swimming in the flames. He turned his gaze to Ralph.

“Mr. Coachley,” Ralph began, “about the Hoffman account—”

“Fuck the Hoffman account.”

Their boss savored the word. He said it like a child on the playground, learning to curse for the very first time.

“Fuck ‘em,” Mr. Coachley roared again, “This isn’t the office, Ralphy. This here is nature, where a man can talk like a man.”

Ralph struggled to follow. “Sir?”

“I didn’t invite you all out here to talk about the damned Hoffman account,” Coachley bellowed, “You’ve all got accounts with Hoffmans and Goldbergs and Feinmans and Fuckits, but I want to know you people before I start with the promotions.”

He kept doing it: that little smirk at the end of the curse, like they could all loosen up with the new cool boss—like they hadn’t heard him say fuck a thousand times before, nestled between phrases like I would and her, if she would just quiet down.

Mr. Coachley proceeded to pull several flasks from his backpack, along with a stack of wax cups he poached from the office water cooler.

“What’ll we toast to?”

Ralph sniffed the brown liquid and tried, unsuccessfully, to conceal a wince.

“To getting to know each other?”

Mr. Coachley grinned. “To advancement.”

They drank with a half-committed round of here heres. It was tequila, and it reminded John of the summers he used to spend in Puerto Morelos attempting to paint iguanas. For a moment, nostalgia draped snug as an extra coat of flesh. Then Mr. Coachley shredded it.

“So Ralphy,” he said, “What’s your favorite team?”

Ralph cleared his throat again and glanced at John, who glanced away.

“The Mets?”

Five more shots, and the sun disappeared. Puddles from the rain slowly turned to ice, trapping fallen leaves and ants who would never get home. Camille drew closer to the fire, but John stayed on the log. He liked the sting. If he moved in, he would have to brave the clouds of ash and noxious drunken banter. Ralph began to teeter on the edge of his seat. The little man struggled to capture words.

“B-buddies?” he stammered, “have you guys seen the other guy?”

“He’s not back yet,” John said. “He’s still finding himself.”

“I don’t know how you could lose yourself at that size,”

said Francis.

Ralph didn’t seem to understand, but Francis and Mr. Coachley cackled. John chuckled too, until he saw Camille. It was true. One man was missing, and whoever he was, he was fat to the point that it defined him. He wasn’t Mr. Coachley’s type of fat—not a layer of pudge to be warn as a symbol of good investments paving the way to a lifetime of even better food—but rather, he was the type of obese that made people stare when they thought he wasn’t looking. The type of antisocial spectacle that stopped coworkers from striking up a conversation at the water cooler and extending the common decency of learning his name. And by the time he was invited on the retreat, it felt too late to ask.

The missing man had been on the hike that afternoon, which Mr. Coachley branded as a team building adventure. The boss had led them down a narrow trail and into a clearing which held a massive wooden seesaw. The object of the game—per Mr. Coachley—was to arrange themselves on the board until both sides were evenly balanced. While Mr. Coachley was delighted with this visual metaphor for corporate synergy, he failed to see a small problem: to strike a balance, their colleague had to stand on one side, and everyone else had to stand on the other. And so they stood, clustered and hovering, watching the fat man walk the plank. After the ordeal, their portly companion had said he was going to take a walk, and “think about some choices.” They hadn’t seen him since.

“We should go look around,” said Camille. “Yeah,” said John.

And no one moved.

After a curt and prickly silence, Mr. Coachley laughed with a tinge of discomfort, then burped rather unexpectedly.

“I’ll sleep under the stars tonight,” he announced, “to keep a lookout.”

“Here here,” Francis echoed. He toasted Mr. Coachley,

then proceeded to further toast himself. Meanwhile, Ralph melted.

“I like the stars,” he cooed. No one responded, but Ralph didn’t stop.

“My mom used to tell me—when I was really young—that the stars were just fragments of the sun. Like when the sun sets and hits the horizon, it breaks into a thousand tiny pieces, and— throughout the night, I guess—the pieces all find their way back together and meet back up at the other end of the sky.”

Mr. Coachley snorted.

“That was goddamn beautiful, Ralphy. Why the hell are you a banker?”

Ralph’s eyes lowered.

“I…I don’t know.”

“Here here,” said John. He toasted Ralph and tossed his shot into the fire. Francis lulled backwards to gaze at the stars.

“Y’know,” Francis said, “I’d like to think my dad’s up there somewhere.”

“Is your dad a pilot?” asked Camille. “No, he was a dentist.”

“Then he’s not up there,” Camille snapped. “But—but, the stars,” Ralph stammered. Camille’s eyes narrowed.

“You wanna play that game, Ralph? Let’s do it. Let’s believe the stars are little lights helping Francis’ daddy walk through the clouds. Ok? Alright. Then what the hell is the moon, Ralph?” Ralph glared. “The moon is a big effing rock.” Francis stifled a laugh. “effing?”

“Fuck,” Ralph spat. “Ok? Is that what I need to do—to get the promotion and all? Do I need to stomp around saying Fuck? Sure. Here it is: fuck you—and you, and you, and you.”

John was mildly surprised when Ralph pointed at him as well. Mr. Coachley stood with the fine-grit sigh of a disappointed father.

“Now, Ralphy—”

“No,” Ralph hissed, “I’m gonna look for the guy.”

“Why?” Francis scoffed. Ralph’s face slowly went from stone back to butter. “Because,” he said gently, “as surprising as it may be, there’s other people in the world besides you.” Then Ralph turned, and he wandered into the underbrush.

Only after that did John realize how cold it had gotten. Camille was quiet again, but she was breathing heavily, and her breath steamed in great clouds around her face. Mr. Coachley huffed and adjusted his bowling pin boxers.

“I’m going to go piss in nature,” the boss announced. “Then, I’m going to bed. Under the goddamn stars.”

Mr. Coachley scanned his lot, almost daring an objection. “Francis,” he said, “I know you’ll join me. John?”

John thought for a moment, then realized he would rather get frostbite alone than share any warmth with his boss.

“No.”

“I will,” said Camille, no doubt hoping Francis would pout at his stolen thunder. Mr. Coachley stood with a grin.

“Then we’ll all roll around in the dirt.”

The rest sat longer, drank more, and ripened quickly. Ice began crawling up the trees. John couldn’t look at Camille because it made him feel like he was going to vomit. He couldn’t watch the world beyond the fire, as the now spinning trees were just as nauseating. Instead, John focused on Francis. The fire’s glow shined distant in the man’s glazed eyes, and his mouth fell slightly ajar. As the smoke blew towards his face, Francis fell into a fit of coughing, which subsided as he mumbled, “…goddamn Red Sox.”

He spat in the dirt, then pitched off the log to land on his knees at the brink of the fire.

“I’m sorry about the thing with the stars,” said Camille. Francis didn’t look at her.

“Stars don’t care,” he said, “and my old man’s dead one way

or another, so he can’t care much.” Francis brushed his hand over the fire, letting the flames lick his fingers.

“And quite honestly,” he mused, “there’s no reason I should care either. Go apologize to Ralphy, maybe.”

Camille sank deeper into her sweatshirt.

“Look, I’m just trying to—”

“Cammie,” Francis snapped, “Let me stop you, honey. When your fire goes out, we’ll cough up your smoke and forget you were ever a spark. Go burn out somewhere else, sweetheart.”

Camille stood. Her teeth ground in harmony with cracking embers.

“How dare you,” she spat. “You’re a trust fund baby in a grown-up’s clothes, who was just too average and unmemorable to make it selling protein on Instagram. And now, just because you have a pile of cash and a penis, you think you can wave your dick around like a magic wand and make senior partner, while I work twice as hard and get half the respect. And when you finally, inevitably get the job at my expense, you’re gonna think it was sharp wit and old money charm that got you to the top. But really, you climbed all the way up because you’re easy to step on. If I had a dollar for every time I’ve seen Mr. Coachley shove his hand up your ass and work your mouth like a puppet, I’d have enough money to buy the company out from under him and fire on the spot that greasy, cologne-soaked, pathetic performance of an honest worker you try to hide behind. And they won’t remember me? Who the fuck are you, Francis?”

He met her with a poisoned smile.

“I’m content.”

Camille returned the same empty grin she gave to every man who looked at her the way she looked at cigarettes. John watched as if she alone had invented fire. As she left, Camille stumbled through the darkness beyond her creation, and Francis hollered after her.

“Don’t bump into the moon, darling!”

Then he tussled John’s hair, walked down the trail, and left a regal silence in his wake.

The world was iced and spinning when John found his tent. He stepped over Mr. Coachley, Camille, and Francis, strewn across the dirt in the center of the campsite. They were anchored in a frigid stillness, sealed in drunken wedlock to the frozen Earth.

Mountains pitched and danced in ancient darkness. The sleeping bag digested him. John was underwater, floating, drowned in tequila, and searching in a primal grief for anything worth looking at. Was that a fire in the distance, or was it a star? It swam in obscurity. Then a voice.

“Can I sleep in here?”

John felt around until light exploded from a hidden flashlight. Camille’s face pierced the blackness.

“It’s fucking freezing out, and the guys want to push through, but I don’t think I can make it.”

John blinked furiously.

“I tried to pitch my own tent,” Camille went on, “but as fate would have it, I’m drunk.”

John snorted, and she smiled softly. Camille climbed into his tent. She wrapped herself in him. Goosebumps rose to greet a stranger’s warmth like nostalgia for someone else’s memory. John watched her breath rise as smoke, and disappear without a trace. He listened to her shallow breathing fall in time with crooning birds, mourning over children lost to the cold. Once again, they found each other bound in quiet solitude.

“I’m sorry I never called again,” John whispered. “I have cancer,” she replied.

In the distance, the fire burned out, and goodness drowned in foul guts.

That night, John has a dream about an island off the coast of Puerto Morelos. He’s painting with oil and fury, and the sun is

broken over the sky, and an old man, guided by the light of lost stars, wanders aimlessly above the world. An iguana falls from his canvas and scurries into the sand, but not before atoning with his father’s eyes. And his father—having traded perspectives with a painted beast—is choking in an intravenous net. For a moment, John wonders if it might snap below the razor’s edge edge of a crisp dollar bill. Then the stars fade, and his island is the moon, and empty space is cold, and he calls for help, but sound is sucked into nothing. No ships will pass by this island. They all sailed away in his youth.

John woke with a headache. Camille laid tense and chapped as rough marble on his chest. Past the human rubble, the forest bloomed in tune with a quiet moaning. It came from somewhere beyond the tent, where the ground was now covered in a heavy layer of snow. Without waking Camille, John wormed his way outside. The sun was sharp. Unforgiving. Mr. Coachley burst from a nearby tent, which he must have set up once the snow started falling.

“Hell of a freeze last night,” he said, “but Francis and I kept each other nice and warm.” Then, Francis spilled out behind Mr. Coachley. The young man shyly wiped the corner of his mouth. He adjusted a pair of oversized bowling pin boxers, and looked at no one.

They walked in silence, following the cries down the trail to the fire pit. When they reached the clearing, Mr. Coachley stopped dead. He watched as Ralph convulsed before him, mewling in a pile of ashes, and clawing at the scab where his lips had frozen away.

The story came later. At the hospital, Ralph explained how he had hiked back up the mountain in search of their missing coworker. As the snow fell, Ralph had lost the trail. He never found their portly companion, but by some miracle, he had found

his way back to the fire with just enough time to save face—at least some of it. Ralph had to use a communication board the hospital usually provided for stroke victims. John was amazed by all the different things it could mean to be frozen.

The office felt cold that night, so Mr. Coachley let them go early. In the elevator, John was the only one to notice Camille was missing. He found her back on the sixtieth floor, standing alone. Camille was staring out the conference room window, a slender silhouette laced against the sunset. She looked like nothing more than a crack in the glass. Outside, the clouds pooled around her head like a dream in an old cartoon.

When John met Camille at the window, he realized she was crying.

“This is going to kill us one day,” John said. Camille smiled through the tears.

“I would say you have no idea, but I might be wrong this time.”

John shrugged. “Let’s skip to the part where you ask if I’m trying to die with you.”

“Déjà vu,” she whispered. “Are you?”

“I don’t think so. You know why I never called again?”

She met his eyes. John turned away.

“I’d like to think my dad’s out there somewhere,” he said. Camille flinched. John thought of stars and broken suns, and lost light, and scarred faces, and suddenly, it seemed like awful poetry how little was said by the one who still had lips.

“I thought I’d be a painter when my dad got sick,” he said. “I stopped so I could work to pay his bills. And then he died anyway. And I’ve been working here for fifteen years. And my dad? He spent everything on me. On the work I wanted to do. You know how long it took me to realize he died disappointed?”

Camille shook her head.

“About twenty minutes. But then I got a paycheck. And you know how long it took me to realize I regretted every minute

of it?”

Camille shook her head.

“About twelve years. When I woke up one day, and found you in my bed, and thought you looked so stunning you deserved to be painted. And I couldn’t do it.”

“John—”

“No, Camille. I really fucked it up. I think I didn’t want to be with someone who made me realize how badly I fucked it up, but I did, and I ran. And then I didn’t call again, and you know what happened?”

“John, I—”

“I fucked it up again, Camille. A second time I threw away the beautiful thing. And I’m sorry.”

Camille wilted. “John. I’m going to die.”

“I know,” John said. “And I’m sorry.”

He could see Camille was holding back tears, and wished more than anything that she would just cry. Instead, she tried to laugh, but choked, then gave John a look reserved for children and injured pets.

“When my fire goes out,” she murmured, “you’ll forget I was even a spark.”

John took her hand. He held her, firm in the way a man lost at sea holds tight to a bottled plea in the second before he lets go. He smiled.

“Fires fade quicker than the people who remind you you’re human.”

Camille sighed. She kept his hand, and watched the city lights struggle to shine through the fog.

“Think the other guy’s still out there?” she asked.

“Maybe,” John said. “But if he is, I hope he never comes back.”

“Why’s that?” she asked.

“Because he did it,” John said. “He escaped.”

I’m wandering the streets of SF, dead of night.

I pass shuddering lampposts barely bursting with dim light.

graffiti lines my vision as I saunter on alone, a lamb to the slaughter; prey to predators unknown.

I’ve become accustomed, yet, I wonder: what’s it like, to twiddle your thumbs while relishing the night? to get to wear headphones without the fear of plight. no need to be so vigilant or brace for fight or flight. what‘s it like to not hold pepper spray (safety off, just in case?) to have the privilege not to carry a switchblade to feel safe?

“What’s it like?”

Cassie Shaw

All Eyes on You Kristie Park

not be raised on horror stories, how not to get killed. learning go for the eyes, since “they’ll be bigger and more skilled.” not be told that “getting taken will be worse than if we died,” “cause if we’re moved to a new location we’ll be tortured, then tossed aside.” not be warned from just a jog — told, “better yet, don’t go outside.” taught to apologize when rejecting men cause ‘they get angry when denied”.

do you have to

tell strangers:

“Hey, haven’t seen ya in awhile!” just to whisper, “I don’t know you, but he’s been following you for a mile.” enter parking lots and start picking up your pace? then peek under your car while wielding keys and mace? practice hitting your emergency speed dial? and stay near bystanders –“since you’ll need witnesses on trial.” wonder why we’re cautious when a guy throws us a smile? it’s cause the most malicious are good at hiding they’re hostile.

Tiburon | Nur SheltonIn this medium, I attempt to render meta, somewhat invisible concepts or occurrences visible through fairly deliberate symbolism. This piece, Speak, represents a reality that I have had to come to terms with, and I believe it to be applicable to others as well. We are cerebral creatures, and with that comes hesitancy and deliberation and oftentimes silence, but through writing we are given a more secure and measured way to communicate complex ideas and emotions—at least, that’s been my experience.

on the first day, the girl walks into the buffet.

the innards of the buffet are vast, vast beyond comprehension. the walls are bare, the floor is barer, and the ceiling is all but invisible. they fade into the murk and dimness of the endless, empty space, which is actually rather deceiving in its perceived emptiness. impossibly long lengths of glittering, rusty metal stretch and wind around the entirety of the building’s insides, eagerly clogging into every inch of free space they can squeeze into. these are the food aisles, carting every single culinary style, food group, and culture one could wish for, served steaming, freezing, lukewarm, raw, overcooked, spiked, and all of the above. where an aisle meets an unyielding corner or some surface or another aisle, it curves around instead, climbing like a sticky insect onto a nearby open space until it can safely deposit itself back onto solid ground.

as if in a competition for dominance with the visual grandeur of the space, relentless, deafening sound spills into every pore of the room; the oblivious clattering of silverware, the phlegmy outbursts of raucous laughter, the piercing hollow pinging of glasses and plates, the mushy grinding and chomping of teeth against oily flesh and sinews and fibers and granulated sugar.

the girl feels nauseous. she leaves.

***

on the second day, the girl walks into the buffet.

the smell of rotting food and artificial sweetness encircles her in a sweaty embrace. before she can decide what to do next, a woman dressed in all black knocks into her. the girl looks up, startled. the woman looks back at her and beams. stacked precariously in her hands is a pile of plates, dripping with grease. split. splat. fat, congealed droplets crash to the dirty ground discordantly.

“are you a waitress?” asks the girl.

the woman chortles, half-chewed food spraying out of her mouth. “waitress?” she grins widely, showing rows of teeth stained brown and gray. “there are no waitresses or waiters here. i’m with my husband and friends for my wedding.” her hot breath wafts into the girl’s face, carrying the oily scents of burger patty and tuna and barbecue sauce. she winks at the girl, and the girl fights back the bile rising in her throat.

the girl tries to breathe shallowly. “for the afterparty?”

“oh, no, no,” says the woman, smacking her lips. “we just had our entire wedding ceremony here. real popular spot, it is. everyone’s talking about how it’s got the best food these days.” she winks again. there’s a smear of barbecue sauce on her chin. “things to look forward to, eh? i knew i wanted to get married here ever since i was a tiny schoolgirl. and then i met the one in here. dreams really do come true.”

the girl tries to smile.

“well, girlie, i’d better be off.” the woman pats her stomach and burps, then shakily balances all the plates on one hand as she pulls out a handkerchief from her pocket and wipes her mouth daintily. “nobody can ever get enough of this place, right? good thing it’s

the buffet | Emily Huang

the woman tucks the handkerchief back into her pocket and begins to saunter off in a food-drunken waddle.

“wait,” says the girl. “where’s your wedding dress?”

the woman pauses and swivels around, eyeing the girl critically. “we don’t believe in that kind of stuff anymore,” she tuts. “it’s all about maximizing cleanliness. this outfit is the best one i own, because it looks the least dirty while eating.” shooting the girl one final pinched smile, the woman turns and strolls away, an air of condescension trailing in her wake.

the girl leaves. ***

on the third day, the girl meets a boy.

he walks in after she has already arrived. she sees him push through the heavy doors, the light from the outside glancing off the bare walls and casting shadows along his angled features. he stands tall, so tall, and so very handsome. and he is standing still, just like her.

she stares and stares until she remembers, foggily, what the woman had said about love and marriage and weddings and food. she takes a few confident strides towards the raw food aisle, empty-handed, fists clenched, brain blank.

out of the corner of her eye, she sees the boy approach. he wears a shy smile. one hand is stuffed into a pocket.

“first time here?” his voice is cool water, low and smooth, running through the girl’s heart.

the girl begins to nod, but then reconsiders and changes it into a vigorous shake.

the boy exhales softly, still smiling. “well, it’s my first time. to be honest, i’m feeling a bit overwhelmed!”

the girl laughs lightly with him, the sound evaporating off her skin. she looks at the boy’s face. it is beautiful; his cheeks are slightly flushed, and his eyes bear a mischievous twinkle. she feels a sudden wave of trust for this boy rush through her body.

she clears her throat and looks down. “it’s actually my first time here, too. technically.” she balls her hand into a fist. “i don’t feel hungry.”

“me neither,” says the boy. he takes her hand, the one that isn’t balled.

she sighs and thinks, no, what i mean to say is, i don’t feel hungry. ever. and i don’t know what’s wrong with me, because there’s all this food here, but i know there must be something wrong with me, because everyone else seems to feel hungry at all the right times and in all the right ways.

she imagines saying it aloud to him. the fantasy feels so relieving and so wrong all at once.

the boy squeezes her hand. “i understand,” he says, “and i think it’s okay to take this slow. we should eat only when we feel hungry.”

the girl turns to face him in awe. she never thought she’d find

someone else like her. the boy returns the stare, looking deeply into her eyes. he clutches her other hand, which has relaxed out of its clench without her noticing. he pulls her closer to him until there are only whispers of space left between their bodies.

“wait,” murmurs the girl, eyelids half-closed. “then what are you doing here?”

and then the boy is kissing her, and she is kissing him back, and as their tongues dance and their hands roam and their breaths increase and entwine, the gluttonous clamor of the buffet shrivels up into an invisible backdrop.

***

on the fourth day, the boy is there again.

as before, he arrives after her, making eye contact with her the moment he steps inside as though he had been looking for her.

he approaches her at a brisk pace before she has even made a beeline for an aisle, and stops his stride when he is between her and a stack of unused plates. he gestures towards them with a hopeful expression.

“there’s lava cake in the eastmost aisle,” he says to her. “my favorite. want to go get some?”

the girl knits her eyebrows. “i’m not hungry,” she says hesitantly, and it comes out sounding like, “i’m not hungry?”

the boy’s face droops a little. the change is to the most minute of degrees, but the girl sees it.

“i’ll walk with you,” she offers, and she does, her arm in his arm, his hand balancing a plate. at the eastmost aisle, he loads his plate with lava cake and pauses, turning to her.

“have some,” he says, his tone taking on a hint of pleading. in his hand is the giant pastry server, laden with another slice of cake.

the girl swallows and stares at the cake slice. it is dense and leaking with burning, fatty, heavy chocolate. “maybe tomorrow.”

the boy’s face droops again, and he drops the cake onto his own plate without another word. the girl watches him eat the cake, forkful by forkful, swallow by swallow. she watches the way his jaw moves as he chews. when he’s finished, they kiss, his tongue pushing globs of chocolatey saliva into her mouth.

***

on the fifth day, the boy is already there.

he is standing by the door; she sees him as soon as she enters. nearly walks into him. in his hand is a plate of lava cake. one single, puny slice.

he thrusts the plate towards her, and her hands instinctively fly up, fingers closing around the rim. he moves to face her, blocking the doors. his face is stamped with desperation and confusion.

“what are we?” he asks her, voice tinged with sadness and hope and anxiety. she looks away as heat floods her cheeks, and he moves with her, trying to stay in her field of vision. “what are we?” he asks again. “why won’t you eat? do you care for me as i do for you? do i mean anything at all to you?” he moves closer to her, and she realizes he does not understand he is blocking her only

exit.

“of course,” replies the girl. “of course.” she looks at the plate again, eyes probing the length of the fork sticking erect out of the slice.

“then why won’t you enjoy my favorite dessert with me?” implores the boy. his hands move to hers, wrapping her fingers around the handle of the fork. she shivers.

“i don’t share my favorite dessert with just anyone,” he continues. “you don’t need to feel very hungry to try a small bite. just one little bite.”

the girl stares hard at her curled fingers, which are trembling so hard that they are causing the fork’s tines to shake within the cake’s flesh.

“please. for me?” ***

she feels his hot breath drench her hair and trickle down her neck. he is close enough for her to feel his heartbeat pounding, pounding. every inch of his body beats anxiously, hopefully. she can’t tell if the air in her nostrils is hers or his. head spinning, she grabs the fork and dislodges it, stuffing a chunk of chocolate into her mouth and biting down. her throat immediately constricts, rejecting the thick, overpowering sweetness. the boy beams, watching her intently.

“that’s it,” he whispers, letting his hands float down her body in a whisper of a caress.

the girl’s eyes begin to water as she chews, but as his hands

continue to traverse the landscape of her figure, she realizes she has never felt so precious, so admired, so loved. she jabs the fork back into the cake’s burnt brown body and sticks another scoop in between her lips, humming with a noise she thought one might make while enjoying something delicious. the boy sighs happily, his burning eyes never leaving her face.

forkful by forkful, swallow by swallow, the girl eats, quickly learning how to force her nausea down and moan in pleasure and gratitude instead.

***

as the girl eats, she begins to bleed.

long slits dash down her breasts and torso and thighs, zippering her open. she feels something inside her below her belly tear open, pooling sharp, sticky warmth between her legs, and something in her chest convulses sporadically. she is becoming nothinged. a dotted line, a question mark, a bleeding placeholder. she ignores it all.

the boy cheers, feeding her another forkful, and leads her to a table where several other people are seated and shoveling food into their mouths with vigor. the girl sits down and bleeds all over the chair and floor, her insides spilling onto their table, but none of them seem to notice. their eyes are trained on their plates, their stomachs and throats growling with desire as they swallow.

the boy claims his own seat and whoops with joy, piling his plate high with an assortment of steaming fats and oily sinews and fibers that emit piercing fumes. he can’t take his eyes off of the girl. every so often, he sets his fork down and clasps the girl’s wet, paling hand in his, proclaiming, i love you, i love you, i love you,

and the girl is crying, and nodding, and shaking, forcing forkful after forkful down her sticky throat. and she can’t stop. she cries and cries, swallowing and nodding and smiling and shaking because she can finally eat, she can finally eat, she can finally eat.

on the sixth day, the girl is nowhere to be seen.

Lemon Jinhyo Huh Tetons Cathy Gao

I hate myself knowing that I cried more for my dead betta fish than when my grandfather passed away.

But I had to grieve that hooked mouth. Those beady bloated eyes. The tiny origami wings it had, once shimmering in the tank as it swam, had grown needled with fin rot holes and were folded into its tiny cardboard casket. Voracious breathes gone ragged, gone silent, then buried under the crumbly soil of a pot outside on the patio.

And so it goes, its playful scales would peel and so would the layers underneath, flesh leaving fish-bones dry to swim among fungi instead. When the 15-liter tank was poured out into the toilet, I traced phantom sensations left in the apartment: the murmur of the water filter, the faint fishy stench in the living room, or the quietest crunch of food pellets in my fish’s jaw.

When my grandfather died, I had no reek to flush or fins to tuck. I had the image, blurred through a spotty Facetime call, of a white marble tomb with sharp corners. The pristine block sat in a familial plot just a mere eight time zones away. Despite the muggy air, the Philippines is soaked in, the tomb looked like it was cold to the touch.

I swear I wanted to cry, but I couldn’t with just a gaze at that tomb.

But even before that, I’d have to collect pieces from phone calls between my mom and her brothers abroad. Kawawa naman siya—a statement of pity. Kumakain naman siya—he’s still eating. I saw a picture of my uncle bringing a scrumptious platter of pork and rice steaming hot to my grandfather’s nursing home for his birthday. But even with his smile of gleaming teeth, there was

dissonance between that image and the scrapbooks we had. This old man, slouched beside his nurse, was the attorney Plaridel, the patriarch of seven sons and one daughter he’d forgotten the names of.

But even before we’d put him in that nursing home, he’d wander around our house in Quezon City with eyes dulled. Not from cataracts, but his vision was diluted by an absence. His steps were light, and he’d whistle melodies from Sinatra or Nat King Cole.

But he’d loop around the hallways like it was the first time he’d found them. There wasn’t recognition in his eyes, only the flickering resemblance of it. And one day, his words regressed to vitriol and confusions, not knowing who we were, or who he was himself. I remember the family’s anger at a man who’d lost his mind and his relocation to the nursing home.

But even before that, my early memories of him are shown through a candy-colored childhood or the muffled headache of jet-lagged vacations. He was a pale-skinned man, back then with an asphalt gray mop of hair. As if to spite the wrinkles forming along his face, he moved with surprising passion when dancing with Lola to the shuffle of Christmas karaoke nights. An uncle would be belting out Pinoy folk-rock, and the floor would thrum with echoes of golden days as Lolo swayed with grinning showmanship. When he was here in SoCal, I half-remember the chalky Altoids he’d munch on, and how I’d stoop down to put DVDs in the TV player for him to watch in the guest room. After he’d thanked me sleepily, I’d scurry back to my room to play with Power Rangers.

At some point between visits, when I was in third grade, he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

But even before that, my mom spun myths of a much different man. One who was sobrang matapang, of a lean body and furious wit in the courthouse. Someone who passed the Bar Exam on the first try, and sipped brandy all night, even when

it burnt through his throat. He was someone the local military had tossed in a cell for being “subversive”, even when all he had done was provide legal counsel for the poor. Instead of cash, he accepted their payments in crops, butchered chicken, or fish.

I heard no end of the fires he stoked, and back in the day, he’d forced my uncles as teens to manage the fish pond in the province, where they netted milkfish. He wanted to see them become slick with the sweat of labor, building walkways of dirt and harvesting. But sometimes they slacked off on hammocks under the blistering sun. Then, when the lookout boy they bribed said their Papa was coming, they’d pounce into the mud, letting it filth their skin, a guise to protect them from the wrath of a God.

I find it hard to cry over a man built from hand-me-down folktales. But maybe one day, I can truly grieve. Once I lay my hands upon his cold marble tomb shaking with stillness. Once I trace his looping steps through the crooked house. Once I trespass into his law firm and pilfer whiffs of manila folders and long-gone tobacco.

I hope to wade knee-deep, among the reeds of the fish pond, where the bones of fish scratch my feet and the memory of shimmering fins straightens my spine. And to walk deeper still, the humid air beating on my back, barefoot in the muddy waters, humming his favorite songs.

let me lay the scene: it is summer in the city. we are lying under the shade of a thousand sins, the whole world lying at our feet, when you tuck my hair behind my ear, tuck your hand in my back pocket & say the words i’ve been waiting for: i’d be lying

if i said i didn’t have feelings for you. now, all that’s left for me to do is say it back, but that would lead to lying

under you when that’s not what i want at all. still, i find myself saying i have feelings for you, too. that’s when you started lying

to me. i know you know i know what you did. while you were with me, you were also lying with someone else, since i refused to lie with you. that august, you were spotted at santa cruz, lying in the sand, your body flush against hers. why won’t you lie with me? i don’t feel like lying when you ask, so i tell the truth: it’s none of your business. you say you know i never meant to hurt you, andrea. & i wonder: why are you always lying?

Outside, it smells like winter. The road quiets even though there’s no snow, just us lighting lamps in your room, humidity shrouding the dorm parking lot outside your window in glittering fog. The dullness of

a dream. I must be making up the way we are dying fast here, because I know you gave me your arm for real on the freeway heading for Pacifica and said pinch me so I know we’re both still alive. We feel old,

but we’re not right. In the church courtyard on campus, tourists have been taking pictures of the statues all week. I picture the statues standing for hundreds of years, watching all these young people running around asking questions. I picture the statues, young once. I wonder when they decided to turn to stone.

Standing on the beach in Pacifica offshore someone’s old prison, I tell you imagine West Japan, a straight shot off the coast from our school. Glitter sticks to my face from last night. If it catches enough light

I wonder if it might pick us up and blow us into the ocean. I tell you come on, let’s start sailing and never stop. You talk about tariffs. Okay, then let’s fix up an ancient car that shouldn’t run, drive all the way to Mexico. You say

you forgot your passport. Back home in the library, your hands brush the glitter off my face. It falls on the carpet, where people’s shoes grind it down. I hope sometime soon the statues lose patience with all this wanting,

come back to life, and explain to us how to go from young to old back to ourselves. It is getting late, and

laundry piles up in both our bedrooms. I trace the burning fairytale on your shoulder and mine you. We feel old, but we’re not, right? Is this what youth feels like? Tell me I’m wrong.

Chamomile tea cools on the window sill, a finch in the doorway. A woman is on the floor, hair in the strands of the carpet. The puddle of her blood is a parallelogram opening. She has never had a looser grip. The firefighters breach the broken door to find her later. The carpet melts into the concrete foundation of her tan house on Steiner Street.

Allison Argueta (visual art) is a junior studying economics and psychology. In her free time, she enjoys reading, writing, and drawing.

Robert Castaneros (poetry) is currently a sophomore studying Political Science and Asian-American Studies. He has done creative writing for a while now, mainly creative non-fiction; however, during his sophomore year, he has been able to explore poetry more! He is especially interested in Asian-American poetics as a means of exploring his Filipino-American identity. Robert loves to sing, read, and watch movies! He also loves the allergen-free lemon blueberry muffins in the dining hall.

Elizabeth Grant (poetry) is a senior at Stanford where she studies Creative Writing. When she’s not working on poetry, her hobbies include gardening and studying constitutional and criminal law.

Emily Huang (prose) is a freshman at Stanford University hailing from the suburbs of northeastern Massachusetts. Her work has been featured by Adroit Journal, The Daphne Review, Apprentice Writer, Hypernova Lit, The Heritage Review, and elsewhere. She is passionate about exploring themes of trauma, family, and religion in her work. In her spare time, Emily takes on the roles of avid bookworm, poi and K-Pop dancer, and film soundtrack lover (the best music in the world, no questions asked).

Jinhyo Huh (visual art) is a sophomore reluctantly studying Computer Science. She was born in Seoul, Korea and had a wonderful childhood full of date trees, stray cats, and blackberries. When she was 7, she moved to Vancouver, Canada, and grew up loving skiing, snowboarding, people, and the sun.

Jacob Langsner (prose) is a 1L at Stanford Law School. He graduated Stanford University in 2021 with a BA in political science and a minor in art history. He continues to write and produce short films, which can be found at jacoblangsner.com, or through his

instagram (@jakelangsner).

Andrea Liao (poetry) is a frosh at Stanford and plans to minor in creative writing on the prose track.

Benjamin Marra (poetry) is a sophomore majoring in English. I edit for the Leland quarterly, and I love poetry and fiction. My particular interests tend to be in the natural world and queer art.

Grace Miller (poetry) is a sophomore majoring in Computer Science from Savannah, GA. In her free time, she enjoys driving over bridges.

Kristofer Roland Nino (prose) is a freshman hoping to major in English with an emphasis on Creative Writing. When he’s not busy being wracked by existential horror, he can be found overanalyzing pop culture, drawing, working at a bookstore, eating cereal, daydreaming, and sometimes even writing poetry or short stories.

Kristie Park (visual art) is a sophomore studying Sociology and Biomechanical Engineering. She is currently interested in exploring themes of isolation and human interaction through her artwork, and enjoys experimenting with bold lines and bright color palettes to present a new perspective on scenes from daily life.

Jordan Pollock (visual art) is currently a junior majoring in English with a Creative Writing emphasis. In addition to writing literary fiction and dabbling in poetry, she sometimes takes up the paintbrush, the pencil, the stylus to create some visual art. In her free time she does a lot of existential pondering and sometimes goes for a walk.

Cassie Shaw (poetry) Within Rm 302 is Cassie: the skater with knee problems from riding goofy, the amiable redhead surrounded by a “scrapyard” of taped sketches, a fridge of fruit she’s swiped from dining halls, and a polaroid wall of visitors who come to her door. She prides herself in serving tea and inquiring strangers about their deepest secrets and idiosyncrasies.

Where do you want to see LQ head in the future? How can we continue to grow, increase our accessibility, and support the artistic community at Stanford?

We would truly appreciate your input. If you have five spare min utes, please take this survey and share your ideas with us: